History of Monopoly

The board game Monopoly has its origin in the early 20th century. The earliest known version, known as The Landlord's Game, was designed by Elizabeth Magie and first patented in 1904, but existed as early as 1902.[1][2][3] Magie, a follower of Henry George, originally intended The Landlord's Game to illustrate the economic consequences of Ricardo's Law of economic rent and the Georgist concepts of economic privilege and land value taxation.[4] A series of board games was developed from 1906 through the 1930s that involved the buying and selling of land and the development of that land. By 1933, a board game already existed much like the modern version of Monopoly that has been sold by Parker Brothers and related companies through the rest of the 20th century, and into the 21st. Several people, mostly in the midwestern United States and near the East Coast of the United States, contributed to its design and evolution.

By the 1970s, the false idea that the game had been created by Charles Darrow had become widely believed; it was printed in the game's instructions for many years,[5] in a 1974 book devoted to Monopoly,[6] and was cited in a general book about toys as recently as 2007.[7][8] Even a guide to family games published for Reader's Digest in 2003 gave credit only to Darrow and none to Elizabeth Magie or any other contributors, erroneously stating that Magie's original game was created in the 19th century and not acknowledging any of the game's development between Magie's creation of the game and the eventual publication by Parker Brothers.[9]

Also in the 1970s, Professor Ralph Anspach, who had himself published a board game intended to illustrate the principles of both monopolies and trust busting, fought Parker Brothers and its then parent company, General Mills, over the copyright and trademarks of the Monopoly board game. Through the research of Anspach and others, much of the early history of the game was "rediscovered" and entered into official United States court records. Because of the lengthy court process, including appeals, the legal status of Parker Brothers' copyright and trademarks on the game was not settled until 1985. The game's name remains a registered trademark of Parker Brothers, as do its specific design elements; other elements of the game are still protected under copyright law. At the conclusion of the court case, the game's logo and graphic design elements became part of a larger Monopoly brand, licensed by Parker Brothers' parent companies onto a variety of items through the present day. Despite the "rediscovery" of the board game's early history in the 1970s and 1980s, and several books and journal articles on the subject, Hasbro (which became Parker Brothers' parent company) did not acknowledge any of the game's history prior to Charles Darrow's involvement on its official Monopoly website as recently as June 2012,[10] nor did they acknowledge anyone other than Darrow in materials published or sponsored by them, at least as recently as 2009.[11]

International tournaments, first held in the early 1970s, continue to the present, although no national tournaments or world championships have been held since 2015. Starting in 1985, a new generation of spin-off board games and card games appeared on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. In 1989, the first of many video game and computer game editions was published. Since 1994,[12] many official variants of the game, based on locations other than Atlantic City, New Jersey (the official setting for the North American version) or London, have been published by Hasbro or its licensees. In 2008, Hasbro permanently changed the color scheme and some of the gameplay of the standard US Edition of the game to match the UK Edition, although the US standard edition maintains the Atlantic City property names.[13] Hasbro also modified the official logo to give the "Mr. Monopoly" character a 3-D computer-generated look, which has since been adopted by licensees USAopoly (The OP), Winning Moves and Winning Solutions. And Hasbro has also been including the Speed Die, introduced in 2006's Monopoly: The Mega Edition by Winning Moves Games, in versions produced directly by Hasbro (such as the 2009 Championship Edition).[14][15]

Game development 1903–1934

[edit]

In 1903, Georgist Lizzie Magie applied for a patent on a game called The Landlord's Game with the object of showing that rents enriched property owners and caused tenants to be impoverished. She knew that some people would find it hard to understand the logic behind the idea and she thought that if the rent problem and the Georgist solution to it were put into the concrete form of a game, it might be easier to demonstrate. She was granted the patent for the game in January 1904. The Landlord's Game became one of the first board games to use a "continuous path", without clearly defined start and end spaces on its board.[16][17] Another innovation in gameplay attributed to Magie is the concept of "ownership" of a place on a game board, such that something would happen to the second (or later) player to land on the same space, without the first player's piece still being present.[17] A copy of Magie's game that she had left at the Georgist community of Arden, Delaware and dating from 1903–1904, was presented for the PBS series History Detectives.[18] This copy featured property groups, organized by letters, later a major feature of Monopoly as published by Parker Brothers.[19][20]

Although The Landlord's Game was patented, and some hand-made boards were made, it was not actually manufactured and published until 1906. Magie and two other Georgists established the Economic Game Company of New York, which began publishing her game.[21] Magie submitted an edition published by the Economic Game Company to Parker Brothers around 1910, which George Parker declined to publish.[21] In the UK, it was published in 1913 by the Newbie Game Company under the title Brer Fox an' Brer Rabbit.[22][23] Shortly after the game's formal publication, Scott Nearing, a professor in what was then known as the Wharton School of Finance and Commerce at the University of Pennsylvania, began using the game as a teaching tool in his classes. His students made their own boards, and taught the game to others.[24] After Nearing was dismissed from the Wharton School, he began teaching at the University of Toledo. A former student of Nearing, Rexford Guy Tugwell, also taught The Landlord's Game at Wharton, and took it with him to Columbia University.[25] Apart from commercial distribution, it spread by word of mouth and was played in slightly variant homemade versions over the years by Quakers, Georgists, university students (including students at Smith College, Princeton, and MIT), and others who became aware of it.[26][27]

A shortened version of Magie's game, which eliminated the second round of play that used a Georgist concept of a single land value tax, had become common during the 1910s, and this variation on the game became known as Auction Monopoly.[28] The auctioning part of the game came through a rule that auctioned any unowned property to all game players when it was first landed on.[29] This rule was later dropped by the Quakers, and in the current game of Monopoly an auction takes place only when an unowned property is not purchased outright by the player that first lands on it.[29][30] That same decade, the game became popular around the community of Reading, Pennsylvania.[29] Another former student of Scott Nearing, Thomas Wilson, taught the game to his cousin, Charles Muhlenberg, around 1915–1916.[29] The original patent on The Landlord's Game expired in 1921. By this time, the hand-made games became known simply as Monopoly.[31][32] Charles Muhlenberg and his wife, Wilma, taught the game to Wilma's brothers, Louis and Ferdinand "Fred" Thun, in the early 1920s.[29]

By 1906, Magie had moved back to Illinois, and married Albert W. Phillips in 1910.[33] She moved to the Washington, D.C. area with her husband by 1923, and re-patented a revised version of The Landlord's Game in 1924 (under her married name, Elizabeth Magie Phillips). This version, unlike her first patent drawing, included named streets as part of the patent application (the games published in 1910 based on her first patent did have named streets, but they had not been mentioned in the 1903 application). Magie sought to regain control over the plethora of hand-made games.[34] For her 1924 edition, a couple of streets on the board were named after Chicago streets and locations, notably "The Loop" and "Lake Shore Drive".[35] This revision also included a special "monopoly" rule and card that allowed higher rents to be charged when all three railroads and utilities were owned, and included "chips" to indicate improvements on properties.[36][37] Magie again approached Parker Brothers about her game, and George Parker again declined, calling the game "too political".[33][38] Parker is, however, credited with urging Magie to take out her 1924 patent.[33]

After the Thuns learned the game, they began teaching its rules to their fraternity brothers at Williams College around 1926.[29] Daniel W. Layman, in turn, learned the game from the Thun brothers (who later tried to sell copies of the game commercially, but were advised by an attorney that they could not patent it, as they were not its inventors).[29][39] Layman later returned to his hometown of Indianapolis, Indiana, and began playing the game with friends there, ultimately producing hand-made versions of the board based on streets of that city.[31] Layman then commercially produced and sold the game, starting in 1932, with a friend in Indianapolis, who owned a company called Electronic Laboratories.[40] This game was sold under the name The Fascinating Game of Finance (later shortened to Finance).[41] Layman soon sold his rights to the game, which was then licensed, produced and marketed by Knapp Electric.[42] The published board featured four railroads (one per side), Chance and Community Chest cards and spaces, and properties grouped by symbol, rather than color.[43][44][45] Also in 1932, one edition of The Landlord's Game was published by the Adgame Company with a new set of rules called Prosperity, also by Magie.[46]

It was in Indianapolis that Ruth Hoskins, a Quaker teaching at Earlham College, learned the game, and took it back to Atlantic City.[47] After she arrived, Hoskins made a new board with Atlantic City street names and railroads. A group member Jesse Raiford, Eugene Raiford's brother, set the property values that are still in use today. Ruth taught it to a group of local Quakers.[48] It has been argued that their greatest contribution to the game was to reinstate the original Lizzie Magie rule of "buying properties at their listed price" rather than auctioning them, as the Quakers did not believe in auctions.[49][50] Another source states that the Quakers simply "didn't like the noise of the auctioneering".[29] Among the group taught the game by Hoskins were Eugene Raiford and his wife, who took a copy of the game with Atlantic City street names to Philadelphia.[51] Due to the Raifords' unfamiliarity with streets and properties in Philadelphia,[51] the Atlantic City-themed version was the one taught to Charles Todd, who in turn taught Esther Darrow, wife of Charles Darrow.[52] After learning the game, Darrow then began to distribute the game himself as Monopoly and never spoke to the Todds again.[29] Darrow initially made the sets of the Monopoly game by hand with the help of his first son, William Darrow, and his wife. Their new sets retained Charles Todd's misspelling of "Marvin Gardens" and the renaming of the Shore Fast Line to the Short Line.[52] Charles Darrow drew the designs with a drafting pen on round pieces of oilcloth,[53] and then his son and his wife helped fill in the spaces with colors and make the title deed cards and the Chance cards and Community Chest cards. After the demand for the game increased, Darrow contacted a printing company, Patterson and White, which printed the designs of the property spaces on square carton boards. Darrow's game board designs included elements later made famous in the version eventually produced by Parker Brothers, including black locomotives on the railroad spaces, the car on "Free Parking", the red arrow for "Go", the faucet on "Water Works", the light bulb on "Electric Company", and the question marks on the "Chance" spaces, though many of the actual icons were created by a hired graphic artist.[54][55][56] While Darrow received a copyright on his game in 1933, its specimens have disappeared from the files of the United States Copyright Office, though proof of its registration remains.[57]

Patent history

[edit]| Patents for Landlord's Game and Monopoly | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Inventor | Reference |

| 1904 | Lizzie J. Magie | [58] |

| 1924 | Elizabeth Magie Phillips | [59] |

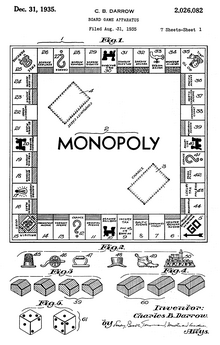

| 1935 | Charles B. Darrow | [60] |

Acquisition by Parker Brothers

[edit]

Darrow first took the game to Milton Bradley and attempted to sell it as his personal invention. They rejected it in a letter dated May 31, 1934.[62] After Darrow sent the game to Parker Brothers later in 1934, they rejected the game as "too complicated, too technical, [and it] took too long to play".[63] Darrow received a rejection letter from the firm dated October 19, 1934.[62] During this time, the "52 design errors" story was invented as a reason why Parker rejected Monopoly, but this has more recently been proven to be part of the Parker-invented "creation myth" surrounding the game.[10][64][65]

In early 1935, however, the company heard about the game's excellent sales during the Christmas season of 1934 in Philadelphia and at F.A.O. Schwarz in New York City. Robert Barton, President of Parker Brothers, contacted Darrow and scheduled a new meeting in New York City.[66] On March 18, Parker Brothers bought Darrow's game, helped him take out a patent on it, and purchased his remaining inventory.[65][67] By April, 1935, the company had learned that Darrow was not the sole inventor of the game, but sought out an affidavit by Darrow to repeat his statements to the contrary, and thus bolster their claim to the game.[29][68] Parker Brothers subsequently decided to buy out Magie's 1924 patent and the copyrights of other commercial variants of the game to claim that it had legitimate undisputed rights to the game.

Robert Barton, president of Parker Brothers, bought the rights to Finance from Knapp Electric later in 1935.[69][70] Finance would be redeveloped, updated, and continued to be sold by Parker Brothers into the 1970s.[71] Other board games based on a similar principle, such as a game called Inflation, designed by Rudy Copeland and published by the Thomas Sales Co., in Fort Worth, Texas, also came to the attention of Parker Brothers management in the 1930s, after they began sales of Monopoly.[72][73] Copeland continued sales of the latter game after Parker Brothers attempted a patent lawsuit against him. Parker Brothers held the Magie and Darrow patents, but settled with Copeland rather than going to trial, since Copeland was prepared to have witnesses testify that they had played Monopoly before Darrow's "invention" of the game.[74] The court settlement allowed Copeland to license Parker Brothers' patents.[75] Other agreements were reached on Big Business by Transogram, and Easy Money by Milton Bradley, based on Daniel Layman's Finance.[76] Another clone, called Fortune, was sold by Parker Brothers, and became combined with Finance in some editions.[77]

Monopoly was first marketed on a broad scale by Parker Brothers in 1935. A Standard Edition, with a small black box and separate board, and a larger Deluxe Edition, with a box large enough to hold the board, were sold in the first year of Parker Brothers' ownership. These were based on the two editions sold by Darrow.[78] Parker Brothers sets were the first to include die-cast metal tokens for playing pieces, initially using a battleship, a cannon, a clothes iron, a shoe, a top hat, and a thimble.[79] George Parker himself rewrote many of the game's rules, insisting that "short game" and "time limit" rules be included.[80] On the original Parker Brothers board (reprinted in 2002 by Winning Moves Games), there were no icons for the Community Chest spaces (the blue chest overflowing with gold coins came later) and no gold ring on the Luxury Tax space. Nor were there property values printed on spaces on the board. The Income Tax was slightly higher (being $300 or 10%, instead of the later $200 or 10%). Some of the designs known today were implemented at the behest of George Parker.[80] The Chance cards and Community Chest cards were illustrated (though some prior editions consisted solely of text), but were without "Rich Uncle Pennybags", who was introduced in 1936.[79]

Late in 1935, after learning of The Landlord's Game and Finance, Robert Barton held a second meeting with Charles Darrow in Boston. Darrow admitted that he had copied the game from a friend's set, and he and Barton reached a revised royalty agreement, granting Parker Brothers worldwide rights and releasing Darrow from legal costs that would be incurred in defending the origin of the game.[81]

Licensing outside the United States

[edit]

In December 1935, Parker Brothers sent a copy of the game to Victor Watson, Sr. of Waddington Games. Watson and his son Norman tried the game over a weekend, and liked it so much that Waddington took the (then extraordinary) step of making a transatlantic "trunk call" to Parker Brothers, the first such call made or received by either company.[82] This impressed Parker Brothers sufficiently that Waddington was granted licensing rights for Europe and the then-British Commonwealth, excluding Canada.[83] Waddingtons version, their first board game, with locations from London substituted for the original Atlantic City ones, was first produced in 1936.[84]

The game was very successful in the United Kingdom and France, but the 1936 German edition, published by Schmidt Spiele, disappeared from the market within three years. This edition, featuring locations in Berlin, was denounced, allegedly by Joseph Goebbels to the Hitler Youth due to the game's "Jewish-speculative character".[85] It is also alleged that the real reason behind the Nazi denouncement was because high-ranking Nazis (i.e. Goebbels, again) lived on streets whose names appeared as those sections of the game board given the highest property values, and did not want to be associated with a game.[86][87] The game last appeared in a pre-World War II Schmidt Spiele catalog in 1938.[88] A German edition with "generic" street and train station names (i.e., not recognizable as any single German city) did not appear until 1953.[85][89] The 1936 German edition, with the original cards and the recognizable Berlin locations, was reprinted in 1982 by Parker Brothers and again in 2003 (in a wooden box), and 2011 (in a red metal tin) by Hasbro.[90][91]

Waddington licensed other editions from 1936 to 1938, and the game was exported from the UK and resold or reprinted in Switzerland, Belgium, Australia, Chile, The Netherlands, and Sweden. In Italy, under the fascists, the game was changed dramatically so that it would have an Italian name, locations in Milan, and major changes in the rules. This was for compliance under Italian law of the period. Italian publishers Editrice Giochi produced the game in Italy until 2009, having held a unique licensing agreement from Parker Brothers and their own copyright dating back to 1935/1936.[7] As of 2009, Hasbro has taken over the publishing of the game in Italy, but have also, for now, kept the Milan-based properties.[92]

In Austria, versions of the game first appeared as Business and Spekulation (Speculation), and eventually evolved to become Das Kaufmännische Talent (DKT) (The Businessman's Talent). Versions of DKT have been sold in Austria since 1940. The game first appeared as Monopoly in Austria in about 1981.[93] The Waddingtons edition was imported into The Netherlands starting in 1937, and a fully translated edition first appeared in 1941.[94]

It has been claimed that Waddingtons later produced special games during World War II which secretly contained files, a compass, a map printed on silk, and real currency hidden amongst the Monopoly money, to aid prisoners of war in escaping from German camps.[95][96] However, this story has come under recent scrutiny and is being disputed.[97] Among the points of dispute is that there are no existing examples and no one who claims to have used or even seen one.

Collector Albert C. Veldhuis features a map on his "Monopoly Lexicon" website showing which versions of the game were remade and distributed in other countries, with the Atlantic City, London, and Paris versions being the most influential.[98] After World War II, homemade games would sometimes appear behind the Iron Curtain, although the game was effectively banned.[99] Monopoly is cited as the board game played most often and most duplicated via hand made copies in the former German Democratic Republic.[100] One official version of the game was printed for the Soviet Union by Parker Brothers in 1988.[101] After the Cold War ended, official editions have been published throughout eastern Europe by Parker, Tonka and Hasbro. Hungary was the first, in 1992,[102] followed by the Czech Republic and Poland in 1993,[103][104] Croatia in 1994,[105] Slovenia in 1996,[106] Romania and a new edition for Russia in 1997,[101][107] and Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Slovakia, all in 2001.[108][109][110][111]

Marketing within the United States in the 1930s

[edit]In 1936, Parker Brothers published four further editions along with the original two: the Popular Edition, Fine Edition, Gold Edition, and Deluxe Edition, with prices ranging from US$2 to US$25 in 1930s money.[112] After Parker Brothers began to release its first editions of the game, Elizabeth Magie Phillips was profiled in the Washington D.C. Evening Star newspaper, which discussed her two editions of The Landlord's Game.[113] In December 1936, wary of the Mah-Jongg and Ping-Pong fads that had left unsold inventory stuck in Parker Brothers' warehouse, George Parker ordered a stop to Monopoly production as sales leveled off. However, during the Christmas season, sales picked up again, and continued a resurgence.[114] In early 1937, as Parker Brothers was preparing to release the board game Bulls and Bears with Darrow's photograph on the box lid (though he had no involvement with the game), a Time magazine article about the game made it seem as if Darrow himself was the sole inventor of both Bulls and Bears and Monopoly:

If it is true that the devil finds work for idle hands to do, the No. 1 U.S. Mephistopheles is currently a mild little Philadelphian named Charles Darrow. Mr. Darrow's claim to the title, based on Monopoly, U.S. parlor craze of 1936, was last week reinforced when Parker Brothers began to distribute his second invention for idle hands. The new Darrow game is Bulls & Bears. Success of Monopoly, which was last week estimated to be in its sixth million and selling faster than ever, gave Bulls & Bears a pre-publication sale of 100,000, largest on record for a new game.

— TIME magazine, "Sport: 1937 Games", February 1, 1937, p. 44.

Parker Brothers' marketing 1940s–1960s

[edit]At the start of World War II, both Parker Brothers and Waddington stockpiled materials they could use for further game production. During the war, Monopoly was produced with wooden tokens in the US, and the game's cellophane cover was eliminated.[115] In the UK, metal tokens were also eliminated, and a special spinner was introduced to take the place of dice. The game remained in print for a time even in the Netherlands, as the printer there was able to maintain a supply of paper.[116] Elizabeth Magie's second patent on The Landlord's Game expired in September, 1941, and it is believed that after the expiration, she was no longer promoted as an inventor of Monopoly.[117] The game itself remained popular during the war, particularly in camps, and soldiers playing the game became part of the product's advertising in 1944.[118]

After the war, sales went from 800,000 a year to over one million. The French and German editions re-entered production, and new editions for Spain, Greece, Finland and Israel were first produced.[119] By the late 1950s, Parker Brothers printed only game sets with board, pieces and materials housed in a single white box.[120] Several copies of this edition were exhibited at the American National Exhibition in Moscow in 1959. All of them were stolen from the exhibit.[121] In the early 1960s, "Monopoly happenings" began to occur, mostly marathon game sessions, which were recognized by a Monopoly Marathon Records Documentation Committee in New York City.[122] In addition to marathon sessions, games were played on large indoor and outdoor boards, within backyard pits, on the ceiling in a University of Michigan dormitory room, and underwater.[123] In 1965, a 30th anniversary set was produced in a special plastic case.[124]

End of Parker Brothers' independence

[edit]Marketing under General Mills 1968–1985

[edit]Parker Brothers was acquired by General Mills in February 1968.[125] The first Monopoly edition in Braille is published in 1973.[126] Also in 1973, as the Atlantic City Commissioner of Public Works considered name changes for Baltic and Mediterranean Avenues, fans of the board game, with support from the president of Parker Brothers, successfully lobbied for the city to keep the names.[127] After Parker Brothers was taken over by General Mills, the Monopoly license to Waddingtons was renegotiated (as was the Clue/Cluedo license to Parker Brothers/General Mills by Waddingtons).[128] By 1974, Parker Brothers had sold 80 million sets of the game.[129] In 1975, another anniversary edition was produced, but this edition came in a cardboard box looking much like a standard edition.[124] Parker Brothers was under management by General Mills as the first six Monopoly Tournaments were held.

Kenner Parker Toys and Kenner Parker Tonka 1985–1991

[edit]Kenner was combined with Parker Brothers and spun off as Kenner Parker Toys in 1985. Regular and Deluxe 50th Anniversary editions of Monopoly were released that same year.[130] The spinoff game Advance to Boardwalk was first published in 1985. Kenner Parker was acquired by Tonka in 1987. The 1987/1988 Monopoly Tournaments were held under Kenner Parker Tonka management.

In the United Kingdom, Monopoly publisher Waddingtons produced its first non-London edition in 1989, creating a Limited Edition based on Leeds as a charity fundraiser.[131]

Monopoly (game show)

[edit]In 1990, Merv Griffin Enterprises turned Monopoly into a prime time game show, airing after Super Jeopardy! on Saturday nights on ABC during that summer. The program was hosted by Mike Reilly and announced by Charlie O'Donnell.

Marketing

[edit]1990s

[edit]Monopoly Junior was first published in 1990. Kenner Parker Tonka was acquired by Hasbro in 1991. An all-Europe edition was published by Parker Brothers in 1991 for the nations of the then European Communities, using the Ecu (European Currency Unit).[132] After acquisition by Hasbro, publication of Monopoly in the US ceased at the Parker Brothers plant in Salem, Massachusetts in November 1991.[130]

In 1994, the license to the company that would become USAopoly was issued, and they produced a San Diego, California edition as their first board. In 1995, a license for new game variations and reprints of Monopoly was granted to Winning Moves Games. See the Localizations, licenses, and spin-offs section below for details on further releases by both companies.

In 1995, a 60th Anniversary edition was released in a gold box.[133] In late 1998, Hasbro announced a campaign to add an all-new token to US standard edition sets of Monopoly. Voters were allowed to select from a biplane, a piggy bank, and a sack of money – with votes being tallied through a special website, via a toll-free phone number, and at FAO Schwarz stores.

In March 1999, Hasbro announced that the winner was the sack of money (with 51 percent of the vote, compared to 29 percent for the biplane and 20 percent for the piggy bank). Thus, the sack of money became the first new token added to the game since the early 1950s.[134] In 1999, Hasbro renamed the Rich Uncle Pennybags mascot "Mr. Monopoly", and released Star Wars: Episode I, Pokémon and Millennium editions of Monopoly.[135][136][137] A second European edition is released in 1999, this time using the Euro as currency, but incorrectly listing Geneva as the capital of Switzerland.[132]

2000s

[edit]A 65th Anniversary Edition was released in a variation of the white box in 2000.[138] In 2001, the European Edition is reissued, correcting the mistake of the 1999 printing, and correctly listing Bern as the capital of Switzerland.[132] In 2005, a 70th Anniversary Edition was released in a silver-metallic tin with a plastic slip case.[139] Also starting in 2005, various "Here & Now" editions were released in multiple countries. The first release of this edition was for the UK market, and its success led to the selection of properties for a US edition by online vote. The most popular properties were released on the US "Here & Now" edition board in 2006. This, in turn, led to a worldwide "Here & Now" edition (released in 2008), along with other national editions (including a second UK "Here and Now" edition) with properties selected by online vote.[140][141][142] The main principle of the "Here & Now" editions was "What if Monopoly had been invented today?"[143]

The first changes to the gameplay of the Monopoly game itself occurred with the publication of both the Monopoly Here & Now Electronic Banking Edition by Hasbro UK and Monopoly: The Mega Edition by Winning Moves Games in 2006. The Electronic Banking Edition uses VISA-branded debit cards and a debit card reader for monetary transactions, instead of paper bills.[144] This edition is available in the UK, Germany, France, Australia and Ireland. A version was released in the US in 2007, albeit without the co-branding by Visa. An electronic counter had been featured in the Stock Exchange editions released in Europe in the early 2000s (decade), and is also a feature of the Monopoly City board game released in 2009.

The Mega Edition has been expanded to include fifty-two spaces (with more street names taken from Atlantic City), skyscrapers (to be played after hotels), train depots, the 1000 denomination of play money, as well as "bus tickets" and a speed die.[145] Shortly after the release of Mega Monopoly in 2006, Hasbro adopted the same blue version of the speed die into a special "Speed Die Edition" of the game. By 2008, the die, now red, became a permanent addition to the game, though its use remains optional there.[146] In 2009's "Championship Edition", use of the speed die is mandatory, as it also became mandatory in most of 2009's Monopoly tournaments.

In addition to permanently adding the speed die in 2008, Hasbro also instituted further changes to the United States standard edition of the board, including making Mediterranean and Baltic Avenues a brown color group, making the Income Tax space a flat $200 (removing the 10% option), changing the colors on the GO space from red to black, increasing the Luxury Tax to $100 (from $75), and changing some Community Chest and Chance cards.[13] The changes in these four areas made the US standard edition more uniform with the UK and modern European editions. In 2009, Winning Moves Games introduced "The Classic Edition", with a pre-2008 game board and cards, re-inclusion of the "sack of money" token, and a plain MONOPOLY logo in the center of the board, with neither the 1985 or 2008 version of "Mr. Monopoly" present.[147] Also in 2009, Monopoly "theme packs" entered the retail market, including the Dog Lovers and Sports Fans editions, which include customized money, replacements for houses and hotels, and custom tokens, without a board.

2010s

[edit]In early 2010, Hasbro began selling the Free Parking and Get out of Jail add-on games, which can be played alone or when a player lands on the respective Monopoly board spaces. If played during a Monopoly game, success at either game gets the winning player a "free taxi ride to any space on the board" or "out of jail free", respectively.[148][149] A new, customizable edition called "U-Build" is also released.[150] Later in 2010, for the 75th anniversary of the game's publication, Hasbro released Monopoly Revolution, giving the game a graphic redesign, as well as returning it to a round shape, which had not been seen since some of Darrow's 1930s custom-made sets.[151] The game includes "bank cards" and keeps track of players' assets electronically, as was introduced in the "Electronic Banking Edition" earlier in the decade.[152] The game also features clear plastic playing pieces for movers, and electronic sound effects, triggered by certain events (for instance, a "jail door slam" sound effect when a player goes to jail). Monopoly Live was announced at the New York Toy Fair in February 2011.[153] The Monopoly Millionaire version of the game was released in 2012.[154]

In early 2013, a board game version of the Monopoly Hotels online game was released.[155] From January 8 to February 5, 2013, through the Monopoly page on Facebook in a campaign called "Save Your Token", Hasbro took votes from the public to make another permanent change in the lineup of game tokens. The token with the lowest number of "Save Your Token" votes will be retired, and replaced with one of five other tokens, depending on which of the new candidates gets the most votes. The potential tokens were a robot, a helicopter, a cat, a guitar or a diamond ring.[156] Neither the biplane nor the piggy bank from the 1998 vote are being considered this time. Early on February 6, it was announced that the iron would be retired for having received the fewest votes, and the cat would be replacing it, having received the most votes.[157] Starting in February 2013, the US discount chain Target began selling a "Golden Token" set with the eight classic tokens and all five candidates.[158] Special editions with the thirteen golden tokens have also been released in the UK and France.[159][160] The first Monopoly game to have the new token lineup was released in June 2013.[161] In 2015, the game celebrated its 80th anniversary with eight tokens from each decade in a special edition.

Monopoly tournaments 1973–2015

[edit]The first Monopoly tournaments were suggested by Victor Watson of Waddington after the World Chess Championship 1972. Such championships are also held for players of the board game Scrabble. The first European Championship was held in Reykjavík, Iceland, the same site as the 1972 World Chess Championship. Accounts differ as to the eventual winner: Philip Orbanes and Victor Watson[162] name John Mair, representing Ireland and the eventual World Monopoly Champion of 1975, as also having won the European Championship.[163] Gyles Brandreth, himself a later European Monopoly Champion, names Pierre Milet, representing France, as the European Champion.[164] One of the reasons there may be differing accounts of the eventual winner is attributable to a minor controversy with the final game. According to Parker Brothers' Randolph "Ranny" P. Barton,[165] an error was made by one of the participants and a protest was filed by an opponent. The judges (Barton, Watson, and a representative from Miro, the French publishers of Monopoly) weighed the options of starting the final game over and delaying the chartered plane that would take them home from Iceland vs allowing the game to stand with the error but allowing them to make their flight. In the end, the judges upheld the result of the game with the error uncorrected.

Victor Watson and Ranny Barton began holding tournaments in the UK and US, respectively. World Champions were declared in the United States in 1973 and 1974 (and are still considered official World Champions by Hasbro). While the 1973 tournament, the first, matched three United States regional champions against the UK champion and thus could be argued as the first international tournament, true multinational international tournaments were first held in 1975.[166] Both authors (Orbanes and Brandreth) agree that John Mair was the first true World Champion, as decided in tournament play held in Washington, D.C. days after the conclusion of the European Championship (which Mair had also won), in November 1975.[167]

By 1982, tournaments in the United States featured a competition between tournament winners in all 50 states, competing to become the United States Champion. National tournaments were held in the US and UK the year before World Championships through 2003–2004 but during the same year as of 2009 (see table, below). The determination of the US champion was changed for the 2003 tournament: winners of an Internet-based quiz challenge were selected to compete, rather than one state champion for each of the 50 states.[168] The tournaments are now typically held every six years. In the past, the US edition Monopoly board was used at the World championship level, while national variants are used at the national level.[169] Since true international play began in 1975, no World champion has come from the US, still considered the board game's "birthplace". However, Dana Terman, two-time US Champion, placed second at the 1980 World Championship, Richard Marinaccio, the 2009 US Champion, placed third at the 2009 World Championship, and Brian Valentine, the 2015 US Representative, placed third at the 2015 World Championship.

Nicolò Falcone of Italy defeated players from 27 countries plus the defending champion in the 2015 World Championship held at The Venetian resort in Macau.[170][171] A World Championship had been planned for 2021, but Hasbro has cancelled it due to the Coronavirus pandemic.

| World Tournament locations and champions | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Location | Winner |

| 1973 | Catskills, New York, US | Lee Bayrd, United States[172] |

| 1974 | New York City, New York, US | Alvin Aldridge, United States[172][173] |

| 1975 | Washington, D.C., US | John Mair, Ireland[172] |

| 1977 | Monte Carlo, Monaco | Cheng Seng Kwa, Singapore[172] |

| 1980 | Bermuda | Cesare Bernabei, Italy[172] |

| 1983 | Palm Beach, Florida, US | Greg Jacobs, Australia[172] |

| 1985 | Atlantic City, New Jersey, US | Jason Bunn, United Kingdom[172] |

| 1988 | London, England | Ikuo Hyakuta, Japan[172] |

| 1992 | Berlin, Germany | Joost van Orten, The Netherlands[172] |

| 1996 | Monte Carlo, Monaco | Christopher Woo, Hong Kong[172] |

| 2000 | Toronto, Ontario, Canada | Yutaka Okada, Japan[174] |

| 2004 | Tokyo, Japan (originally scheduled for Hong Kong)[175] | Antonio Zafra Fernandez, Spain[176] |

| 2009 | Las Vegas, Nevada, US | Bjørn Halvard Knappskog, Norway[177] |

| 2015 | Macau | Nicolò Falcone, Italy[178] |

| United States Monopoly Championship winners | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Location | Winner, Hometown |

| 1973 | Catskills, New York | Lee Bayrd, Los Angeles, California[179] |

| 1974 | New York City, New York | Alvin Aldridge, Dayton, Ohio[173][179] |

| 1975 | Atlantic City, New Jersey | A.E. "Gus" Gostomelsky, Skokie, Illinois[179][180] |

| 1977 | New York City, New York | Dana Terman, Wheaton, Maryland[179] |

| 1979 | New York City, New York | Dana Terman, Wheaton, Maryland[179] |

| 1982 | Washington, D.C. | Jerome Dausman, Olney, Maryland[179] |

| 1984 | Los Angeles, California | Jim Forbes[179] |

| 1987 | Washington, D.C. | Gary Peters, Boca Raton, Florida[179] |

| 1991 | New York City, New York | Gary Peters, Boca Raton, Florida[179] |

| 1995 | New York City, New York | Roger Craig, Harrisburg, Illinois[179] |

| 1999 | Las Vegas, Nevada | Matt Gissel, St. Albans, Vermont[179] |

| 2003 | Atlantic City, New Jersey | Matt McNally, Las Vegas, Nevada[179] |

| 2009 | Washington, D.C. | Rick Marinaccio, Buffalo, New York[181] |

| 2015 | Online Selection Process | Brian Valentine, Washington, D.C.[182] |

| Canada Monopoly Championship winners | |

|---|---|

| Year | Winner, Hometown |

| 1975 | Susan Touchbourne, Toronto |

| 1976 | Greg Henkel, Winnipeg |

| 1977 | Greg Henkel, Winnipeg |

| 1980 | David Brooks, Concord |

| 1983 | David Brooks, Concord |

| 1985 | David Brooks, Concord |

| 1988 | Cara Buffett, North Sydney |

| 1992 | Jay Bleiweiss, Toronto |

| 1995 | Bill Bartel, Winnipeg |

| 2000 | Bill Bartel, Winnipeg |

| 2004 | Leon Vandendooren, Edmonton |

| 2009 | Will Lusby, Ottawa[183] |

| 2015 | Andrea Cameron, Holland Landing[184] |

Localizations, licenses, and spin-offs

[edit]The original hand made editions of the Monopoly game had been localized for the cities or areas in which it was played, and Parker Brothers has continued this practice. Their version of Monopoly has been produced for international markets, with the place names being localized for cities including London and Paris and for countries including the Netherlands and Germany, among others. By 1982, Parker Brothers stated that the game "has been translated into over 15 languages...".[185] In 2009, Hasbro reported that Monopoly is officially published in 27 languages, and has been licensed by them in 81 countries.[186] In 2013, Hasbro stated that the game is now available in 43 languages and 111 countries.[187]

The game has also inspired official spin-offs, such as the board game Advance to Boardwalk from 1985. There have been six card games: Water Works from 1972, Free Parking from 1988, Express Monopoly from 1993, Monopoly: The Card Game from 1999, Monopoly Deal from 2008 and Monopoly Millionaire Deal from 2012. Finally, there have been two dice games: Don't Go to Jail from 1991 and an update, Monopoly Express, (2006–2007). A second product line of games and licenses exists in Monopoly Junior, first published in 1990. In the late 1980s, official editions of Monopoly appeared for the Master System, Commodore 64, and Commodore 128.[188] A television game show, produced by King World Productions, was attempted in the summer of 1990, but lasted for only 12 episodes. In 1991–1992, official versions appeared for the Apple Macintosh and Nintendo's NES, SNES, and Game Boy.[189] In 1995, as Hasbro (which had taken over Kenner Parker Tonka in 1991) was preparing to launch Hasbro Interactive as a new brand, they chose Monopoly and Trivial Pursuit to be their first two CD-ROM games.[190] The Monopoly CD-ROM game also allowed for play over the Internet.[191] CD-ROM versions of the officially licensed Star Wars and FIFA World Cup '98 editions also were released.[192] Later CD-ROM exclusive spin-offs, Monopoly Casino and Monopoly Tycoon, were also produced under license.

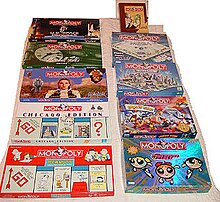

Various manufacturers of the game have created dozens of officially licensed versions, in which the names of the properties and other elements of the game are replaced by others according to the game's theme. The first such license was awarded in 1994, to the company that became USAopoly, starting with a San Diego edition of Monopoly and later including themes such as national parks, Star Trek, Star Wars, Nintendo, Disney characters, Pokémon, Peanuts, various particular cities (such as Las Vegas and New York City), states, colleges and universities, the World Cup, NASCAR, individual professional sports teams, and many others.[193] USAopoly also sells special corporate editions of Monopoly.[194] Official corporate editions have been produced for Best Buy, the Boy Scouts of America, Cornwell Quality Tools, FedEx, Target, Marriott and UPS, among others.[195] In 1995, a second license was awarded to Winning Moves Games in Massachusetts.[196] Winning Moves has produced a new board game and card games based on Monopoly in the United States. Winning Moves also produces official localized editions of the game in the UK, France, Germany and Australia.[197][198][199][200] The Doctor Who 50th Anniversary Edition Monopoly is a special case, having been originally produced by Winning Moves in the UK, and resold by USAopoly within the US.[201] A third license was awarded in 2000 by Hasbro to Winning Solutions, Inc., which produces specialty deluxe editions mostly for sale by specialized retailers.[202] Other licensed localized editions of the game are being published in Nigeria and The Netherlands, among other locations.[203][204]

When creating some of the modern licensed editions, such as the Looney Tunes and The Powerpuff Girls editions of Monopoly, Hasbro included special variant rules to be played in the theme of the licensed property. Infogrames, which has published a CD-ROM edition of Monopoly, also includes the selection of "house rules" as a possible variant of play. Electronic Arts, which publishes current digital versions of the game, such as for the Wii, also includes the selection of certain house rules.

Unofficial versions of the game, which share some of the same playing features, but also incorporate changes so as not to infringe on copyrights, have been created by firms such as Late for the Sky Production Company and Help on Board. These are done for smaller cities, sometimes as charity fundraisers, and some have been created for college and university campuses. Others have non-geographical themes such as Wine-opoly and Chocolate-opoly. There is also a version called Make Your Own -OPOLY, which allows players to customize all the game equipment and rules.[205]

Before the creation of Hasbro Interactive, and after its later sale to Infogrames, official computer and video game versions have been made available on many platforms. In addition to the versions listed above, they have been produced for Amiga, BBC Micro, Game Boy Advance, Game Boy Color, GameCube, IBM compatibles, Nintendo 64, PlayStation, PlayStation 2, Sega Genesis, Xbox, and mobile phones. A version for Windows CE was planned in 1999.[206] A handheld electronic game was first released in 1998 that allowed for one human player against up to three player-selected or randomly chosen AI "personalities" out of five.[207] A Nintendo DS release (along with Battleship, Boggle, and Yahtzee) has been published (by Atari), as well as a stand-alone edition for the same console (by EA). In 2001, Stern released a pinball machine version of Monopoly, designed by Pat Lawlor.[208]

House rules and custom rules

[edit]The official Parker Brothers rules and board remained largely unchanged from 1936 to 2008. Ralph Anspach argued against this during an on-air conversation with The Monopoly Book author Maxine Brady in 1975, calling it an end to "steady progress" and an impediment to progress.[209] Several authors who have written about the board game have noted many of the "house rules" that have become common among players, although they do not appear in Parker Brothers' rules sheets. Gyles Brandreth included a section titled "Monopoly Variations", Tim Moore notes several such rules used in his household in his foreword, Phil Orbanes included his own section of variations, and Maxine Brady noted a few in her preface.[210][211][212][213] Authors Noel Gunther and Richard Hutton published Beyond Boardwalk and Park Place in 1986, as a guide, per the cover, "to making Monopoly fun again", by introducing new variations of rules and strategies.[214] R. Wayne Schmittberger, a former editor of Games magazine, acknowledged the work of Gunther and Hutton in his own 1992 guide New Rules for Classic Games (which includes several pages of Monopoly variations and suggestions that vary from the standard rules of the game).[215]

Anti-Monopoly, Inc. vs. General Mills Fun Group, Inc. court case 1976–1985

[edit]Starting in 1974, Parker Brothers and its then corporate parent, General Mills, attempted to suppress publication of a game called Anti-Monopoly, designed by San Francisco State University economics professor Ralph Anspach and first published the previous year.[19] Anspach began to research the game's history, and argued that the copyrights and trademarks held by Parker Brothers should be nullified, as the game came out of the public domain. Among other things, Anspach discovered the empty 1933 Charles B. Darrow file at the United States Copyright Office, testimony from the Inflation game case that was settled out of court, and letters from Knapp Electric challenging Parker Brothers over Monopoly. As the case went to trial in November 1976, Anspach produced testimony by many involved with the early development of the game, including Catherine and Willard Allphin, Dorothea Raiford and Charles Todd. Willard Allphin attempted to sell a version of the game to Milton Bradley in 1931, and published an article about the game's early history in the UK in 1975.[216] Raiford had helped Ruth Hoskins produce the early Atlantic City games.[217] Even Daniel Layman was interviewed, and Darrow's widow was deposed.[218][219] The presiding judge, Spencer Williams, originally ruled for Parker Brothers/General Mills in 1977, allowing the Monopoly trademark to stand, and allowing the companies to destroy copies of Anspach's Anti-Monopoly.[11][220] Anspach appealed.

In December 1979, the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in favor of Professor Anspach, with an opinion that agreed with the facts about the game's history and differed from Parker Brothers' "official" account.[221] The court also upheld a "purchasing motivation" test (described in the decision as a "Genericness Doctrine"), a "test by which the trademark was valid only if consumers, when they asked for a Monopoly game, meant that they wanted Parker Brothers' version...".[221][222] This had the effect of potentially nullifying the Monopoly trademark, and the court returned the case to Judge Williams.[221] Williams heard the case again in 1980, and in 1981 he again held for Parker Brothers.[223][224] Anspach appealed again, and in August 1982 the appeals court again reversed.[225][226] The case was then appealed by General Mills/Parker Brothers to the United States Supreme Court, which decided not to hear the case in February 1983, and denied a petition for rehearing in April.[227] This allowed the appeals court's decision to stand and further allowed Anspach to resume publication of his game.[228][229]

With the trademark nullified, the name "Monopoly" entered the public domain, where the naming of games was concerned, and a profusion of non-Parker-Brothers variants were published. Parker Brothers and other firms lobbied the United States Congress and obtained a revision of the trademark laws.[222][230][231] The case was finally settled in 1985, with Monopoly remaining a valid trademark of Parker Brothers, and Anspach assigning the Anti-Monopoly trademark to the company but retaining the ability to use it under license.[11][232] Anspach received compensation for court costs and the destroyed copies of his game, as well as unspecified damages. He was allowed to resume publication with a legal disclaimer.[233] Anspach later self-published a book about his research and legal fights with General Mills, Kenner Parker Toys, and Hasbro.

Legal status

[edit]Parker Brothers/Hasbro now claims trademark rights to the name and its variants, and has asserted it against others such as the publishers of Ghettopoly.[234][235] Professor Anspach assigned the Anti-Monopoly trademark back to Parker Brothers, and Hasbro now owns it.[11] Anspach's game remains in print. The previous publishers were a company called Talicor,[236] but the game is currently distributed and sold by University Games worldwide.[237][238]

Various patents have existed on the game of Monopoly and its predecessors, such as The Landlord's Game, but all have now expired. The specific graphics of the game board, cards, and pieces are protected by copyright law and trademark law, as is the specific wording of the game's rules.

Monopoly as a brand

[edit]

Parker Brothers created a few accessories and licensed a few products shortly after it began publishing the game in 1935. These included a money pad and the first stock exchange add-on in 1936, a birthday card, and a song by Charles Tobias (lyrics) and John Jacob Loeb (music).[239][240] At the conclusion of the Anti-Monopoly case, Kenner Parker Toys began to seek trademarks on the design elements of Monopoly. It was at this time that the game's main logo was redesigned to feature "Rich Uncle Pennybags" (now "Mr. Monopoly") reaching out from the second "O" in the word Monopoly.[241] To commemorate the game's 50th anniversary in 1985, the company commissioned artist Lou Brooks to redesign and illustrate the main logo as a red street sign-like banner, as well as the character Rich Uncle Pennybags reaching out of the "O". Brooks was also hired at the time to develop and illustrate the game's special "Commemorative Edition" embossed tin box packaging. The art was also carried over onto the more traditional cardboard game box which was revised for the anniversary.[242][243]

All items stamped with the red MONOPOLY logo also feature the word "Brand" in small print. In the mid-1980s, after the success of the first "collector's tin anniversary edition" (for the 50th anniversary), an edition of the game was produced by the Franklin Mint, the first edition to be published outside Parker Brothers. At about the same time, McDonald's started its first Monopoly game promotions, considered the company's most successful, which continue to the present.[244] The twentieth such promotion was sponsored in 2012.[245]

In recent years, the Monopoly brand has been licensed onto a line of slot machines built by WMS Gaming (first introduced in 1998, six models had been made by 2000, and over 20 by 2005).[246][247][248] The slots were named "Most Innovative Gaming Product in 1999 and voted "most popular" in 2001.[249][250] The brand has also been licensed onto instant-win lottery tickets, and lines of 1:64 scale model cars produced by Johnny Lightning, which also included collectible game tokens.[251][252] Other licenses have been issued for clothing and accessories, including a line of bathroom accessories.[253] Licensee Winning Moves Games also had a Monopoly Calculator that could be used as a standard calculator, or used to aid in transactions during a game.[254]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Sawyer, Keith. "Monopoly: Invention Through Collaboration." (April 15, 2024)The Science of Creativity.

- ^ Pilon, Mary (February 13, 2015). "Monopoly's Inventor: The Progressive Who Didn't Pass 'Go'". New York Times. Retrieved February 14, 2015.

- ^ A US patent was granted in 1904 but in the autumn of 1902 an article describing the game was published in The Single Tax Review. See THE LANDLORDS' GAME

- ^ Parlett, David (1999). The Oxford History of Board Games. Oxford University Press. p. 352. ISBN 0-19-212998-8.

- ^ Monopoly Instructions from a 1999 edition, at hasbro.com

- ^ Brady, Maxine (1974). The Monopoly Book: Strategy and Tactics of the World's Most Popular Game (Fourth Printing, December 1974 ed.). David McKay Company, Inc. pp. 14–20. ISBN 0-679-20292-7.

- ^ a b Albertarelli, Spartaco (2000). "1000s Ways to Play Monopoly" (PDF). Board Games Studies (3). Research School CNWS, Leiden University, The Netherlands: 117–121. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 June 2013. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

- ^ Wallace, David; Wexler, Bruce (2007). The Illustrated Directory of Toys. Colin Gower Enterprises Ltd. p. 463. ISBN 978-0-681-63614-9.

- ^ Glenn, Jim; Denton, Carey (2003). The Treasury of Family Games. Amber Books Ltd. p. 15. ISBN 0-7621-0431-7.

- ^ a b "Monopoly – History & Fun Facts". Hasbro. Archived from the original on June 14, 2012. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- ^ a b c d Pilon, Mary (October 20, 2009). "How a Fight Over a Board Game Monopolized an Economist's Life". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved May 28, 2013.

- ^ "Monopoly" (PDF). Parker Brothers. 1997. Retrieved 2017-02-04.

- ^ a b Orbanes, Philip E. (2013). Monopoly, Money, and You: How to Profit from the Game's Secrets of Success (Nook E-Book ed.). McGraw Hill Education. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-07-180844-6.

- ^ "Speed Die Edition" Archived 2015-09-06 at the Wayback Machine page at about.com

- ^ Monopoly Standard Edition page at amazon.com

- ^ Orbanes, Philip E. (2006). Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game & How it Got that Way. Da Capo Press. p. 10. ISBN 0-306-81489-7.

- ^ a b Parlett, David (March–April 2007). "Monopolizing History". The American Interest. Archived from the original on 23 May 2013. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ^ Transcript of "Episode 2 2004 – Board Games, Arden, Delaware" Archived 2015-02-23 at the Wayback Machine. History Detectives.

- ^ a b Ketcham, Christopher (19 October 2012). "Monopoly is Theft". The Stream. Harper's Magazine. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- ^ Landlord's Game 1903 Arden Rules Analysis, by Thomas Forsyth

- ^ a b Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, p. 22.

- ^ Brer Fox an' Brer Rabbit photographs on tt.tf via the Internet Archive.

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, p. 23.

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly Companion, Second edition. p. 17.

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, p. 30.

- ^ Ideafinder.com page Archived 2006-07-01 at the Wayback Machine on the history of Monopoly

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "From Berks to Boardwalk" originally published in the Winter 1978 Historical Review of Berks County.

- ^ Monopoly Instructions and Rules from 2007 (including the Speed Die) from Hasbro.com

- ^ a b Wolfe, Burton (1976). "The Monopolization of Monopoly: Daniel W. Layman, Jr". Adena.com. The San Francisco Bay Guardian. Retrieved 4 June 2013.

- ^ Costello, The Greatest Games of All Time, p. 62

- ^ a b c Costello, Matthew J. (1991). The Greatest Games of All Time. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 60. ISBN 0-471-52975-3.

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, p. 31.

- ^ Kennedy, Rod Jr. (2004). Monopoly: The Story Behind the World's Best-Selling Game (First ed.). Gibbs Smith. p. 11. ISBN 1-58685-322-8.

- ^ Orbanes, Philip (1999). The Monopoly Companion: The Players Guide (Second ed.). Adams Media Corporation. p. 16. ISBN 1-58062-175-9.

- ^ Parlett, pp. 352–353.

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, p. 33.

- ^ "Louis & Fred Thun" Archived 2009-11-30 at the Wayback Machine, by Burton H. Wolfe, on adena.com

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, p. 45.

- ^ Kennedy. p. 12.

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, p. 46.

- ^ Passing Go: Early Monopoly, 1933–1937 by "Clarence B. Darwin" (pseudonym for David Sadowski), Folkopoly Press, River Forest, Illinois. Photograph on p. 197.

- ^ First Edition of Finance, by Electronic Laboratories, Inc.

- ^ Second Edition of Finance, by Knapp Electric, Inc.

- ^ Landlord's Game and Prosperity page.

- ^ Walsh, Tim (2004). The Playmakers: Amazing Origins of Timeless Toys. Keys Publishing. p. 48. ISBN 0-9646973-4-3.

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly Companion Second edition. p. 20.

- ^ Anspach, The Billion Dollar Monopoly Swindle, p. 140.

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, p. 52.

- ^ a b Eugene Raiford's letter to Vince Leonard dated 2 January 1964.

- ^ a b Orbanes, Monopoly Companion, Second edition. p. 21.

- ^ Images for the Archived 2013-10-24 at the Wayback Machine Monopoly: An American Icon exhibit at the National Museum of Play at The Strong, including a round hand-made set by Darrow from 1933

- ^ Walsh, The Playmakers, p. 49.

- ^ Anspach, The Billion Dollar Monopoly Swindle, p. 134.

- ^ Hinebaugh, Jeffrey P. (2009). A Board Game Education: Building Skills for Academic Success. Rowman & Littlefield Education. p. 72. ISBN 978-1-60709-260-5.

- ^ Anspach, The Billion Dollar Monopoly Swindle, pp. 148–149.

- ^ US patent 748262, Magie, Lizzie J., "Game board", issued 1904-01-05

- ^ US patent 1509312, Phillips, Elizabeth Magie, "Game board", issued 1924-09-23

- ^ US patent 2026082, Darrow, Charles B., "Board game apparatus", published 1935-12-31, issued 1935-12-31, assigned to Parker Brothers Inc

- ^ Early Monopoly Game Box Designs.

- ^ a b Walsh. Page 51. The original rejection letters from Milton Bradley and Parker Brothers are reproduced on this page.

- ^ Orbanes, Philip E. (2004). The Game Makers: The Story of Parker Brothers (First ed.). Harvard Business School Press. p. 92. ISBN 1-59139-269-1.

- ^ Shaw, William (16 December 2008). "Toy stories: Combination of luck and skill that gave birth to some of our favourite games". The Telegraph. London. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- ^ a b Hinebaugh, A Board Game Education, p. 72

- ^ Brady. The Monopoly Book. Page 18.

- ^ Orbanes. The Game Makers. Page 93.

- ^ Wolfe, Burton (1976). "The Monopolization of Monopoly: Parker Brothers". The San Francisco Bay Guardian. Retrieved 4 June 2013.

- ^ Spooner, Ken. "The Knapp Electric Company". The Knapps Lived Here. Spoonercentral.com. Retrieved 4 June 2013.

- ^ Wolfe, Burton (1976). "The Monopolization of Monopoly: The $10,000 Buyout". Adena.com. The San Francisco Bay Guardian. Retrieved 4 June 2013.

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly Companion Second edition. Page 24.

- ^ Rules of Rudy Copeland's Inflation Game.

- ^ Orbanes, The Game Makers. Page 103.

- ^ Anspach, The Billion Dollar Monopoly Swindle, pages 100–101.

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, pages 75–76.

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, page 76.

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, page 78.

- ^ Orbanes, Philip. "Monopoly Memories", booklet, published in 2002 by Winning Moves Games. Included with the reproduction of the 1935 Parker Brothers Monopoly Deluxe Edition set. Page 6.

- ^ a b Hinebaugh, A Board Game Education, p. 73

- ^ a b Orbanes. The Game Makers. Page 95.

- ^ Orbanes, The Game Makers. Page 98.

- ^ Watson, Victor (2008). The Waddingtons Story: From the early days to Monopoly, the Maxwell bids, and into the next millennium. Jeremy Mills Publishing. p. 78. ISBN 978-1-906600-36-5.

- ^ Orbanes, The Game Makers. Pages 98–99

- ^ Watson, The Waddingtons Story, pp. 79-80.

- ^ a b Glonnegger, Erwin (1999). Das Spiele-Buch (Erweiterte Neuauflage ed.). Drei Magier Verlag. p. 115. ISBN 3-9806792-0-9.

- ^ Orbanes, The Game Makers. Page 103

- ^ Tönnesmann, Andreas (2011). Monopoly: Das Spiel, die Stadt und das Glück (First ed.). Verlag Klaus Wagenbach. pp. 49–51. ISBN 978-3-8031-5181-0.

- ^ Wenzel, Sebastian (April 2013). "Monopoly". In Geithner, Michael; Thiele, Martin (eds.). Nachgemacht: Spielekopien aus der DDR. DDR Museum Verlag. pp. 37–40. ISBN 978-3-939801-18-4.

- ^ Tönnesmann, Monopoly. Page 56

- ^ German edition games through 1985 Archived 2012-09-18 at the Wayback Machine, by Albert C. Veldhuis.

- ^ German edition games 1986–present Archived 2012-09-18 at the Wayback Machine, by Albert C. Veldhuis.

- ^ Monopoly Lexicon Archived 2006-10-06 at the Wayback Machine page for Italy, by Albert C. Veldhuis.

- ^ Monopoly Lexicon Archived 2007-02-20 at the Wayback Machine page for Austrian Standard Editions.

- ^ Monopoly Lexicon Archived 2007-02-20 at the Wayback Machine page for early Monopoly editions in The Netherlands, in Dutch.

- ^ Walsh. Page 56.

- ^ Orbanes. The Game Makers. Color photographic insert, page 10.

- ^ "Monopoly Lexicon" Archived 2012-11-01 at the Wayback Machine page for early Monopoly editions from Great Britain.

- ^ English introductory page Archived 2006-10-11 at the Wayback Machine to the Monopoly Lexicon website.

- ^ "Monopoly Lexicon" Archived 2011-07-21 at the Wayback Machine page showing three hand made examples of Monopoly from the German Democratic Republic

- ^ Wenzel, Sebastian (April 2013). "Monopoly". In Geithner, Michael; Thiele, Martin (eds.). Nachgemacht: Spielekopien aus der DDR. DDR Museum Verlag. p. 32. ISBN 978-3-939801-18-4.

- ^ a b "Monopoly Lexicon" Archived 2010-11-24 at the Wayback Machine page for Russia.

- ^ "Monopoly Lexicon" Archived 2012-10-24 at the Wayback Machine page for Hungary.

- ^ "Monopoly Lexicon" Archived 2012-09-25 at the Wayback Machine page for the Czech Republic

- ^ "Monopoly Lexicon" Archived 2012-04-19 at the Wayback Machine page for Poland

- ^ "Monopoly Lexicon" Archived 2012-09-25 at the Wayback Machine page for Croatia

- ^ "Monopoly Lexicon" Archived 2012-09-25 at the Wayback Machine page for Slovenia

- ^ "Monopoly Lexicon" Archived 2012-10-24 at the Wayback Machine page for Romania

- ^ "Monopoly Lexicon" Archived 2012-09-25 at the Wayback Machine page for Estonia

- ^ "Monopoly Lexicon" Archived 2012-09-25 at the Wayback Machine page for Latvia

- ^ "Monopoly Lexicon" Archived 2012-09-25 at the Wayback Machine page for Lithuania

- ^ "Monopoly Lexicon" Archived 2012-09-25 at the Wayback Machine page for Slovakia

- ^ Orbanes. Monopoly Memories. Pages 5–6.

- ^ Sadowski, Passing Go. Page 139.

- ^ Brady, The Monopoly Book. Page 20.

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, pp. 93–94.

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, p. 94.

- ^ Whitehill, Bruce (1999). "American Games: A Historical Perspective" (PDF). Board Games Studies (2). Research School CNWS, Leiden University, The Netherlands: 116–141. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 20, 2008. Retrieved April 19, 2013.

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, p. 98.

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, pp. 100–101.

- ^ Orbanes. Monopoly Memories. p. 2

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, page 107.

- ^ Brady. p. 25.

- ^ Brady. pp. 26–27.

- ^ a b Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Popular Game, photo insert, p. 25.

- ^ Watson, Victor. The Waddingtons Story. p. 81.

- ^ "Monopoly Lexicon" Archived 2013-07-03 at archive.today page for special U.S. Editions

- ^ Brady, pp. 21–24.

- ^ Watson, Victor. The Waddingtons Story. p. 82.

- ^ Brady. p. 20

- ^ a b Albert Vehduis' Archived 2013-07-03 at archive.today page of US Monopoly editions, 1985–present

- ^ Watson, Victor. The Waddingtons Story. pp. 180–181.

- ^ a b c Albert Veldhuis' Archived 2013-05-07 at the Wayback Machine overview of Monopoly collecting.

- ^ BoardGameGeek page for Monopoly 60th Anniversary Edition.

- ^ Hasbro's news release for the new game token in its 1998–1999 campaign via the Internet Archive.

- ^ Business Wire Press Release Archived 2014-07-14 at the Wayback Machine naming the winner of the 1999 United States Monopoly Championship, and referring to game's mascot as Mr. Monopoly. Release dated October 19, 1999 archived at The Free Library

- ^ Press Release, dated October 14, 1999 featuring Pokémon-themed products, including Monopoly.

- ^ Business Wire Press Release Archived 2014-07-14 at the Wayback Machine dated February 2, 1999, archived at The Free Library.

- ^ BoardGameGeek page for 65th Anniversary Edition

- ^ BoardGameGeek page for 70th Anniversary Edition.

- ^ Hasbro.com (US) Archived 2012-12-15 at the Wayback Machine page for Monopoly Here & Now World Edition.

- ^ "Calgary vies for Monopoly real estate". CBC News. January 13, 2010.

- ^ BoardGameGeek list of "Here & Now" themed releases, with dates.

- ^ Monopoly: Here and Now page on YouTube.

- ^ "Monopoly Takes A Chance On Plastic" from Sky News. Accessed July 24, 2006.

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, p. 188.

- ^ Monopoly rules including "Speed Die" and "Classic" variations, from Hasbro.com.

- ^ Winning Moves' Archived 2013-05-08 at the Wayback Machine Monopoly: The Classic Edition p.

- ^ Hasbro (US) Archived 2012-06-03 at the Wayback Machine page for "Free Parking" minigame.

- ^ Hasbro (US) Archived 2012-06-03 at the Wayback Machine page for "Get out of Jail" minigame.

- ^ BoardGameGeek page for U-Build Monopoly

- ^ BoardGameGeek page for Monopoly Revolution.

- ^ Hasbro.com description page

- ^ Sorrel, Charlie (9 February 2011). "New Electronic Monopoly with Evil, All-Seeing Tower". Wired. Retrieved 17 June 2013.

- ^ BoardGameGeek page for Monopoly Millionaire

- ^ BoardGameGeek page for Monopoly Hotels

- ^ Truitt, Brian (8 January 2013). "Token change for Monopoly to replace an iconic piece". USA Today. Retrieved 9 January 2013.

- ^ "Meow! Hasbro unveils new token for Monopoly game". CBS News. Retrieved 6 February 2013.

- ^ Peckham, Matt (January 9, 2013). "Which Monopoly Piece Would You Vote Off the Board?". Time. Retrieved April 4, 2018.

- ^ Press Release Archived 2013-09-10 at the Wayback Machine for UK Golden Token Edition

- ^ Sales page Archived 2013-07-01 at archive.today for a Golden Token Edition release in France

- ^ Hasbro Toy Shop page for 2013 Standard Edition set, including cat token.

- ^ Interview with Victor Watson for "Under the Boardwalk", 5/23/2009

- ^ Orbanes. Monopoly Companion Second Edition. p. 156.

- ^ Brandreth, Gyles (1985). The Monopoly Omnibus (First hardcover ed.). Willow Books. p. 185. ISBN 0-00-218166-5.

- ^ Interview with Randolph P. Barton for "Under the Boardwalk", 7/28/2008

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, p. 116.

- ^ Watson, Victor. The Waddingtons Story. p. 85.

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, p. 155.

- ^ Brandreth. p. 187.

- ^ Under the Boardwalk, LLC. "Under the Boardwalk: The Monopoly Story – 2015 Monopoly Championship Info".

- ^ "Home – 2015 U.S. Monopoly Game Quiz".

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j 1973–1995 World Champions are listed in Philip Orbanes' Monopoly Companion, second edition, p. 171.

- ^ a b "For Those Who Can't Get Enough Of Monopoly, Here Are 1) A Book For Novices And 2) A World Champion". CNN. 24 February 1975. Archived from the original on February 15, 2013.

- ^ Information on the 2000 Archived 2006-09-07 at the Wayback Machine World Monopoly Championship from Mind Sports Worldwide's MindZine.

- ^ 2003 U.S. Tournament "Fun Facts" from hasbro.com via Internet Archive.

- ^ Press Release on Hasbro.com naming the 2004 World Monopoly Champion via Internet Archive.

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly, Money, and You, p. 150

- ^ "Under the Boardwalk". Twitter.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l 1973–2003 US Champions are listed in Philip Orbanes's Monopoly Companion, third edition, p. 169.

- ^ "It's only a game". The Daily Reporter. October 27, 1977.

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly, Money, and You, p. 107

- ^ "USA Representative Chosen! – 2015 U.S. Monopoly Game Quiz".

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly, Money, and You, p. 17

- ^ "Canada Crowns a Monopoly Champion!". 9 December 2015. Archived from the original on 2015-07-01. Retrieved 2015-05-06.

- ^ Quotation from the inside cover of the game booklet included with the special Canadian Edition of Monopoly, published in 1982.

- ^ "Hasbro's Monopoly History and Fun Facts page". Archived from the original on 2009-08-10. Retrieved 2010-01-02.

- ^ Monopoly History on hasbro.com.

- ^ Orbanes, Philip E. (1988). The Monopoly Companion (First ed.). Bob Adams, Inc. p. 190. ISBN 1-55850-950-X.

- ^ List of electronic version release dates on monopolycollector.com.

- ^ U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission 10-Q Quarterly Report for Hasbro, filed November 15, 1995. A launch date of October 25, 1995 for Hasbro Interactive is given in the report.

- ^ Hasbro Annual Report, filed with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission on March 29, 1996.

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly Companion Second Edition. p. 185.

- ^ USAopoly Archived 2015-07-02 at the Wayback Machine About Us page

- ^ USAopoly Corporate Sales Archived 2007-05-13 at the Wayback Machine information

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, pp. 203–204.

- ^ Winning Moves Games About Us page

- ^ Localized Monopoly Editions Archived 2013-02-07 at the Wayback Machine in the UK

- ^ Localized Monopoly Editions Archived 2015-01-01 at the Wayback Machine in Germany

- ^ Localized Monopoly Editions Archived 2013-07-16 at the Wayback Machine in France

- ^ Client list for localized/special Monopoly Editions in Australia

- ^ Game box and rules: Doctor Who 50th Anniversary Edition Monopoly, published 2012 by USAopoly in the United States

- ^ Winning Solutions, Inc. Archived 2013-03-08 at the Wayback Machine About Us page

- ^ Localized Monopoly Editions Archived 2016-01-17 at the Wayback Machine in The Netherlands

- ^ Bestman Games' website featuring the first "City Edition" of Monopoly for Africa: Lagos, Nigeria

- ^ Make Your Own -OPOLY, the first do it yourself board game. Archived 2006-02-21 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hasbro Interactive Press Release dated January 7, 1999.

- ^ Monopoly Handheld game instructions

- ^ Monopoly Pinball page Archived 2006-09-09 at the Wayback Machine at sternpinball.com.

- ^ Anspach, p. 303.

- ^ Brandreth, pp. 169–174.

- ^ Moore, Tim (2002). Do Not Pass Go: From the Old Kent Road to Mayfair. Vintage UK, division of Random House. p. 4. ISBN 0-09-943386-9.

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly Companion, Second Edition. pp. 140–142.

- ^ Brady, p. 10

- ^ Gunther, Noel; Hutton, Richard (1986). Beyond Boardwalk and Park Place. Bantam. ISBN 0-553-34341-6.

- ^ Schmittberger, R. Wayne (1992). New Rules for Classic Games. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 4. ISBN 0-471-53621-0.

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, page 121.

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, page 122.

- ^ Anspach, The Billion Dollar Monopoly Swindle, pages 104–106 and pages 134–135.

- ^ The Anspach Archives Collection description. A list of letters and court depositions used in the Anti-Monopoly case is given on pages 4-19.

- ^ Anspach, The Billion Dollar Monopoly Swindle, page 249.

- ^ a b c Anti-Monopoly, Inc. v. General Mills Fun Group, Inc., 611 F.2d 296 (9th Cir. 1979-12-20).

- ^ a b Orbanes, The Game Makers. Page 170.

- ^ Anti-Monopoly, Inc. v. General Mills Fun Group, Inc., 515 F.Supp. 448 (N.D. Cal. 1981-05-11).

- ^ Anspach, pages 269–271.

- ^ Anti-Monopoly, Inc. v. General Mills Fun Group, Inc., 684 F.2d 1316 (9th Cir. 1982-08-26).

- ^ Anspach, page 273.

- ^ Anspach, page 286.

- ^ Partial scan of the United States Supreme Court decision Archived 2006-10-05 at the Wayback Machine to not hear the Anti-Monopoly, Inc. vs. General Mills Fun Group, Inc. case.

- ^ Parlett, page 354.

- ^ See H.R. 4460, and S. 1440, United States Congress, First Session, 1983, H.R. 6285 and S. 1990, 98th United States Congress, Second Session, 1984. This was signed into Public Law 98-620, by Ronald Reagan on November 8, 1984.

- ^ Text of the "Trademark Clarification Act of 1984" [PDF].

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, pages 120–125.

- ^ Anspach, page 301

- ^ Bennett, Chris B. (13 March 2013). "Racially Insensitive Game Finds New Home On Amazon". Seattle Medium. Retrieved 2 Jan 2017.

- ^ Bennett, Chris B. "Racially Insensitive Game Finds New Home On Amazon". District Chronicles. Archived from the original on 22 January 2016. Retrieved 2 Jan 2017.

- ^ Collins, Doug (November–December 1998). "Go to Court, Go Directly to Court". Washington Free Press. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- ^ University Games Archived 2007-09-29 at the Wayback Machine USA website, Anti-Monopoly page

- ^ University Games website; Anti-Monopoly page

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, Appendix II, page 199

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, photo insert page 29.

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, pages 136–137.

- ^ American Showcase Volume 9 (1986) p. 281. New York. ISBN 0-931144-36-1.

- ^ Texas Monthly, Contributors, November 2008.

- ^ Orbanes, Monopoly: The World's Most Famous Game, pages 135–136.

- ^ McDonald's Monopoly 2012 page Archived 2013-05-09 at archive.today - note the 20th Edition logo.

- ^ U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission 8-K Filing dated September 28, 1998

- ^ WMS Press Release for a renewal of the license to produce Monopoly-themed slot machines, dated September 16, 2003

- ^ WMS Press Release Archived 2013-06-30 at archive.today dated September 6, 2005, citing "over 20 titles of MONOPOLY-branded games".

- ^ Business Wire Press Release Archived 2016-03-05 at the Wayback Machine, dated January 14, 1999, archived at The Free Library

- ^ WMS Press Release dated June 28, 2001, with results from Casino Player Magazine.

- ^ Illinois Lottery's "Pick and Play" US$5 MONOPOLY lottery tickets via Internet Archive

- ^ Ohio Lottery Monopoly US$2 Instant Game via Internet Archive

- ^ Monopoly Bathroom Accessories on Canada-shops.com

- ^ Monopoly Calculator Archived 2016-03-05 at the Wayback Machine 1999 press release.

External links

[edit]Official sites

[edit]History

[edit]- U.S. patent 748,626 – Patent for the first version of The Landlord's Game, Issued on Jan 5, 1904

- U.S. patent 1,509,312 – Patent for the second version of The Landlord's Game, Issued on Sep 23, 1924

- U.S. patent 2,026,082 – Patent awarded to C.B. Darrow for Monopoly on December 31, 1935

- The History of The Landlord's Game and Monopoly.

- History of Monopoly at World of Monopoly

- Online photo album of many historical U.S. Monopoly sets, from Charles Darrow's sets through the 1950s from the Fernandez Collection Sundown Farm and Ranch

- Another online photo album of early Parker Brothers and Waddington sets, in 1935–1954.

- Under the Boardwalk – The MONOPOLY Story – Film detailing the early history of the game with interviews including Phil Orbanes, Randolph Barton, Victor Watson, and Charles Darrow II.