Agriculture in the United States

in north central Idaho

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Economy of the United States |

|---|

|

shows a tractor plowing a crop field

Agriculture is a major industry in the United States, which is a net exporter of food.[1] As of the 2017 census of agriculture, there were 2.04 million farms, covering an area of 900 million acres (1,400,000 sq mi), an average of 441 acres (178 hectares) per farm.[2]

Agriculture in the United States is highly mechanized, with an average of only one farmer or farm laborer required per square kilometer of farmland for agricultural production.

Although agricultural activity occurs in every U.S. state, it is particularly concentrated in the Central Valley of California and in the Great Plains, a vast expanse of flat arable land in the center of the nation, in the region west of the Great Lakes and east of the Rocky Mountains. The eastern wetter half is a major corn and soybean-producing region known as the Corn Belt, and the western drier half is known as the Wheat Belt because of its high rate of wheat production.[3] The Central Valley of California produces fruits, vegetables, and nuts. The American South has historically been a large producer of cotton, tobacco, and rice, but it has declined in agricultural production over the past century. Florida leads the nation in citrus production and is the number two producer of oranges in the world behind only Brazil.

The U.S. has led developments in seed improvement, such as hybridization, and in expanding uses for crops from the work of George Washington Carver to bioplastics and biofuels. The mechanization of farming and intensive farming have been major themes in U.S. history, including John Deere's steel plow, Cyrus McCormick's mechanical reaper, Eli Whitney's cotton gin, and the widespread success of the Fordson tractor and the combine harvester. Modern agriculture in the U.S. ranges from hobby farms and small-scale producers to large commercial farms that cover thousands of acres of cropland or rangeland.

History

[edit]

Corn, turkeys, tomatoes, potatoes, peanuts, and sunflower seeds constitute some of the major holdovers from the agricultural endowment of the Americas.

Colonists had more access to land in the colonial United States than they did in Europe. The organization of labor was complex including free persons, slaves and indentured servants depending on the regions where either slaves or poor landless laborers were available to work on family farms.[4]

European agricultural practices greatly affected the New England landscape. Colonists brought livestock over from Europe which caused many changes to the land. Grazing animals required a lot of land and food and the act of grazing itself destroyed native grasses, which were being replaced by European species. New species of weeds were introduced and began to thrive as they were capable of withstanding the grazing of animals, whereas native species could not.[5]

The practices associated with keeping livestock also contributed to the deterioration of the forests and fields. Colonists would cut down the trees and then allow their cattle and livestock to graze freely in the forest and never plant more trees. The animals trampled and tore up the ground so much as to cause long-term destruction and damage.[5]

Soil exhaustion was a huge problem in New England agriculture. Farming with oxen did allow the colonist to farm more land but it increased erosion and decreased soil fertility. This was due to deeper plow cuts in the soil that allowed the soil more contact with oxygen causing nutrient depletion. In grazing fields in New England, the soil was being compacted by the large number of cattle and this did not give the soil enough oxygen to sustain life.[5]

In the United States, farms spread from the colonies westward along with the settlers. In cooler regions, wheat was often the crop of choice when lands were newly settled, leading to a "wheat frontier" that moved westward over the course of years. Also very common in the antebellum Midwest was farming corn while raising hogs, complementing each other especially since it was difficult to get grain to market before the canals and railroads. After the "wheat frontier" had passed through an area, more diversified farms including dairy cattle generally took its place. Warmer regions saw plantings of cotton and herds of beef cattle. In the early colonial South, raising tobacco and cotton was common, especially through the use of slave labor until the Civil War. With an established source for labor, and the development of the cotton gin in 1793, the South was able to maintain an economy based on the production of cotton. By the late 1850s, the South produced one-hundred percent of the 374 million pounds of cotton used in the United States. The rapid growth in cotton production was possible because of the availability of slaves.[6] In the northeast, slaves were used in agriculture until the early 19th century.[7] In the Midwest, slavery was prohibited by the Freedom Ordinance of 1787.

The introduction and broad adoption of scientific agriculture since the mid-19th century contributed to economic growth in the United States. This development was facilitated by the Morrill Act and the Hatch Act of 1887 which established in each state a land-grant university (with a mission to teach and study agriculture) and a federally funded system of agricultural experiment stations and cooperative extension networks which place extension agents in each state.

Soybeans were not widely cultivated in the United States until the early 1930s, and by 1942 it became the world's largest soybean producer, due in part to World War II and the "need for domestic sources of fats, oils, and meal". Between 1930 and 1942, the United States' share of world soybean production grew from 3% to 47%, and by 1969 it had risen to 76%. By 1973 soybeans were the United States' "number one cash crop, and leading export commodity, ahead of both wheat and corn".[8] Although soybeans developed as the top cash crop, corn also remains as an important commodity. As the basis for "industrial food," corn is found in most modern day items at the grocery store. Aside from items like candy and soda, which contain high fructose corn-syrup, corn is also found in non-edible items like the shining wax on store advertisements.[9]

Significant areas of farmland were abandoned during the Great Depression and incorporated into nascent national forests. Later, "Sodbuster" and "Swampbuster" restrictions written into federal farm programs starting in the 1970s reversed a decades-long trend of habitat destruction that began in 1942 when farmers were encouraged to plant all possible land in support of the war effort. In the United States, federal programs administered through local Soil and Water Conservation Districts provide technical assistance and partial funding to farmers who wish to implement management practices to conserve soil and limit erosion and floods. [10]

Farmers in the early United States were open to planting new crops, raising new animals and adopting new innovations as increased agricultural productivity in turn increased the demand for shipping services, containers, credit, storage, and the like. [11]

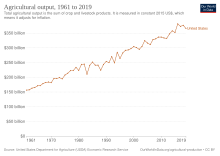

Although four million farms disappeared in the United States between 1948 and 2015, total output from the farms that remained more than doubled. The number of farms with more than 2,000 acres (810 ha) almost doubled between 1987 and 2012, while the number of farms with 200 acres (81 ha) to 999 acres (404 ha) fell over the same period by 44%.[12]

Farm productivity increased in the United States from the mid-20th century until the late-20th century when productivity began to stall.[13]

From 1986 to 2018 about 30 million acres of cropland were abandoned.[14]

Production

[edit]| Crop | Ranking | Output

(000 tons) |

Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| corn | 1 by far | 392,000 | |

| soy | 1 | 123,600 | surpassed by Brazil in 2020[15] |

| wheat | 4 | 51,200 | behind China, India and Russia |

| sugar beet | 3 | 30,000 | behind Russia and France |

| sugar cane | 10 | 31,300 | |

| potato | 5 | 20,600 | behind China, India, Russia and Ukraine |

| tomatoes | 3 | 12,600 | behind China and India |

| cotton | 3 | 11,400 | behind China and India |

| rice | 12 | 10,100 | |

| sorghum | 1 | 9,200 | |

| grape | 3 | 6,800 | behind China and Italy |

| orange | 4 | 4,800 | behind Brazil, China and India |

| apple | 2 | 4,600 | behind China |

| lettuce and chicory | 2 | 3,600 | behind China |

| barley | 3,300 | ||

| onion | 3 | 3,200 | behind China and India |

| peanut | 3 | 2,400 | behind China and India |

| almonds | 1 | 1,800 | |

| beans | 1,700 | ||

| watermelon | 1,700 | ||

| rapeseed | 1,600 | ||

| carrots | 3 | 1,500 | behind China and Uzbekistan |

| strawberry | 2 | 1,300 | behind China |

| cauliflower and broccoli | 3 | 1,200 | behind China and India |

| sunflower seed | 960 | ||

| oats | 10 | 814 | |

| lemon | 8 | 812 | |

| tangerine | 804 | ||

| pear | 3 | 730 | behind China and Italy |

| green pea | 3 | 722 | behind China and India |

| peaches | 6 | 700 | |

| walnut | 2 | 613 | behind China |

| pistachio | 2 | 447 | behind Iran |

| lentils | 3 | 381 | behind Canada and India |

| spinach | 2 | 384 | behind China |

| plum | 4 | 368 | behind China, Romania and Serbia |

| tobacco | 4 | 241 | behind China, Brazil and India |

In addition to smaller productions of other agricultural products, such as melon (872), pumpkin (683), grapefruit (558), cranberry (404), cherry (312), blueberry (255), rye (214), olive (138), and others.[16]

Major agricultural products

[edit]

Tonnes of United States agriculture production, as reported by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the U.N. in 2003 and 2013 (ranked roughly in order of value):[17]

| Millions of Tonnes in | 2003 | 2013 |

|---|---|---|

| Corn | 256.0 | 354.0 |

| Cattle meat | 12.0 | 11.7 |

| Cow's milk, whole, fresh | 77.0 | 91.0 |

| Chicken meat | 14.7 | 17.4 |

| Soybeans | 67.0 | 89.0 |

| Pig meat | 9.1 | 10.5 |

| Wheat | 64.0 | 58.0 |

| Cotton lint | 4.0 | 2.8 |

| Hen eggs | 5.2 | 5.6 |

| Turkey meat | 2.5 | 2.6 |

| Tomatoes | 11.4 | 12.6 |

| Potatoes | 20.8 | 19.8 |

| Grapes | 5.9 | 7.7 |

| Oranges | 10.4 | 7.6 |

| Rice, paddy | 9.1 | 8.6 |

| Apples | 3.9 | 4.1 |

| Sorghum | 10.4 | 9.9 |

| Lettuce | 4.7 | 3.6 |

| Cottonseed | 6.0 | 5.6 |

| Sugar beets | 30.7 | 29.8 |

Other crops appearing in the top 20 at some point in the last 40 years were: tobacco, barley, and oats, and, rarely: peanuts, almonds, and sunflower seeds. Alfalfa and hay would both be in the top ten in 2003 if they were tracked by FAO.

Crops

[edit]Value of production

[edit]

| Major Crops in the U.S. | 1997 (in US$ billions) |

2014 (in US$ billions) |

|---|---|---|

| Corn | $24.4 | $52.3 |

| Soybeans | $17.7 | $40.3 |

| Wheat | $8.6 | $11.9 |

| Alfalfa | $8.3 | $10.8 |

| Cotton | $6.1 | $5.1 |

| Hay, (non-Alfalfa) | $5.1 | $8.4 |

| Tobacco | $3.0 | $1.8 |

| Rice | $1.7 | $3.1 |

| Sorghum | $1.4 | $1.7 |

| Barley | $0.9 | $0.9 |

| Source | 1997 USDA – NASS reports,[18] | 2015 USDA-NASS reports,[19] |

Note alfalfa and hay are not tracked by the FAO and the production of tobacco in the United States has fallen 60% between 1997 and 2003.

Yield

[edit]Heavily mechanized, U.S. agriculture has a high yield relative to other countries. As of 2004:[20]

- Corn for grain, average of 160.4 bushels harvested per acre (10.07 t/ha)

- Soybean for beans, average of 42.5 bushels harvested per acre (2.86 t/ha)

- Wheat, average of 43.2 bushels harvested per acre (2.91 t/ha, was 44.2 bu/ac or 2.97 t/ha in 2003)

Livestock

[edit]

The major livestock industries in the United States:

| Type | 1997 | 2002 | 2007 | 2012 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cattle and calves | 99,907,017 | 95,497,994 | 96,347,858 | 89,994,614 |

| Hogs and pigs | 61,188,149 | 60,405,103 | 67,786,318 | 66,026,785 |

| Sheep and lambs | 8,083,457 | 6,341,799 | 5,819,162 | 5,364,844 |

| Broilers & other meat chickens |

1,214,446,356 | 1,389,279,047 | 1,602,574,592 | 1,506,276,846 |

| Laying hens | 314,144,304 | 334,435,155 | 349,772,558 | 350,715,978 |

Goats, horses, turkeys and bees are also raised, though in lesser quantities. Inventory data is not as readily available as for the major industries. For the three major goat-producing states—Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas—there were 1.2 million goats at the end of 2002. There were 5.3 million horses in the United States at the end of 1998. There were 2.5 million colonies of bees at the end of 2005.

Farm type or majority enterprise type

[edit]Farm type is based on which commodities are the majority crops grown on a farm. Nine common types include:[24][25][26]

- Cash grains includes corn, soybeans and other grains (wheat, oats, barley, sorghum), dry edible beans, peas, and rice.

- Tobacco

- Cotton

- Other field crops includes peanuts, potatoes, sunflowers, sweet potatoes, sugarcane, broomcorn, popcorn, sugar beets, mint, hops, seed crops, hay, silage, forage, etc. Tobacco and cotton can be included here if not in their own separate category.

- High-value crops includes fruits, vegetables, melons, tree nuts, greenhouse, nursery crops, and horticultural specialties.

- Cattle

- Hogs

- Dairy

- Poultry and eggs

One characteristic of the agricultural industry that sets it apart from others is the number of individuals who are self-employed. Frequently, farmers and ranchers are both the principal operator, the individual responsible for successful management and day-to-day decisions, and the primary laborer for his or her operation. For agricultural workers that sustain an injury, the resultant loss of work has implications on physical health and financial stability.[27]

The United States has over 14,000 certified organic farms, covering more than 5 million acres, though this is less than 1% of total US farmland. The output of these farms has grown substantially since 2011, and exceeded US$7.5 billion in 2016.[28]

Governance

[edit]

Agriculture in the United States is primarily governed by periodically renewed U.S. farm bills. Governance is both a federal and a local responsibility with the United States Department of Agriculture being the federal department responsible. Government aid includes research into crop types and regional suitability as well as many kinds of federal government subsidies, price supports and loan programs. U.S. farmers are not subject to production quotas and some laws are different for farms compared to other workplaces.[29][30][31]

Labor laws prohibiting children in other workplaces provide some exemptions for children working on farms with complete exemptions for children working on their family's farm.[32] Children can also gain permits from vocational training schools or 4-H clubs which allow them to do jobs they would otherwise not be permitted to do.

A large part of the U.S. farm workforce is made up of migrant and seasonal workers, many of them recent immigrants from Latin America. Additional laws apply to these workers and their housing which is often provided by the farmer.

Farm labor

[edit]This article is written like a personal reflection, personal essay, or argumentative essay that states a Wikipedia editor's personal feelings or presents an original argument about a topic. (May 2022) |

Farmworkers in the United States have unique demographics, wages, working conditions, organizing, and environmental aspects. According to The National Institute for Occupational Safety & Health in Agricultural Safety, approximately 2,112,626 full-time workers were employed in production agriculture in the US in 2019 and approximately 1.4 to 2.1 million hired crop workers are employed annually on crop farms in the US.[33] A study by the USDA found the average age of a farmworker to be 33. In 2017, the Department of Labor and Statistics found the median wage to be $23,730 a year, or $11.42 per hour.

The types of farmworkers include field crop workers, nursery workers, greenhouse workers, supervisors, etc.[34] The United States Department of Labor findings for the years 2019-2020 report that 63 percent of crop workers were born in Mexico, 30 percent in the mainland United States or Puerto Rico, 5 percent in Central America, and 2 percent in other regions.[35] The amount of farm labor in the United States has changed substantially: in 1870, almost 50 percent of the U.S. population was employed in agriculture;[36] As of 2008[update], less than 2 percent of the population is directly employed in agriculture.[37][38]

Potential health and safety issues that may be associated with farm work include vehicle rollovers, falls, musculoskeletal injuries, hazardous equipment, grain bins, pesticides, unsanitary conditions, and respiratory disease. According to the United States Department Of Labor, farmworkers are at risk of work-related lung diseases, noise-induced hearing loss, skin diseases, and certain cancers related to chemical use.[39] Farm workers also suffer disproportionately from heat stress, with fewer than average seeking treatment. While some progress has been made, many farm workers continue to struggle for fair pay, proper training, and safe working conditions.[40]

Occupational safety and health

[edit]Agriculture ranks among the most hazardous industries due to the use of chemicals and risk of injury.[41][42] Farmers are at high risk for fatal and nonfatal injuries (general traumatic injury and musculoskeletal injury), work-related lung diseases, noise-induced hearing loss, skin diseases, chemical-related illnesses, and certain cancers associated with chemical use and prolonged sun exposure.[42][43][44] In an average year, 516 workers die doing farm work in the U.S. (1992–2005). Every day, about 243 agricultural workers suffer lost-work-time injuries, and about 5% of these result in permanent impairment.[45] Tractor overturns are the leading cause of agriculture-related fatal injuries, and account for over 90 deaths every year. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health recommends the use of roll over protection structures on tractors to reduce the risk of overturn-related fatal injuries.[45]

Farming is one of the few industries in which families (who often share the work and live on the premises) are also at risk for injuries, illness, and death. Agriculture is the most dangerous industry for young workers, accounting for 42% of all work-related fatalities of young workers in the U.S. between 1992 and 2000. In 2011, 108 youth, less than 20 years of age, died from farm-related injuries.[46] Unlike other industries, half the young victims in agriculture were under age 15.[47] For young agricultural workers aged 15–17, the risk of fatal injury is four times the risk for young workers in other workplaces[48] Agricultural work exposes young workers to safety hazards such as machinery, confined spaces, work at elevations, and work around livestock. The most common causes of fatal farm-related youth injuries involve machinery, motor vehicles, or drowning. Together these three causes comprise more than half of all fatal injuries to youth on U.S. farms.[49] Women in agriculture (including the related industries of forestry and fishing) numbered 556,000 in 2011.[42] Agriculture in the U.S. makes up approximately 75% of the country's pesticide use. Agricultural workers are at high risk for being exposed to dangerous levels of pesticides, whether or not they are directly working with the chemicals.[44] For example, with issues like pesticide drift, farmworkers are not the only ones exposed to these chemicals; nearby residents come into contact with the pesticides as well.[50] The frequent exposure to these pesticides can have detrimental effects on humans, resulting in adverse health reactions associated with pesticide poisoning.[51][52] Migrant workers, especially women, are at higher risk for health issues associated with pesticide exposure due to lack of training or appropriate safety precautions.[53][54] United States agricultural workers experience 10,000 cases or more of physician-diagnosed pesticide poisoning annually.[55]

Research centers

[edit]Farmer suicide

[edit]

Farmers' suicides in the United States refers to the instances of American farmers taking their own lives, largely since the 1980s, partly due to their falling into debt, but as a larger mental-health crisis among U.S. agriculture workers. In the Midwest alone, over 1,500 farmers have taken their own lives since the 1980s. It mirrors a crisis happening globally: in Australia, a farmer dies by suicide every four days; in the United Kingdom, one farmer a week takes their own life, in France it is one every two days. More than 270,000 farmers have died by suicide since 1995 in India.[57][58]

Farmers are among the most likely to die by suicide, in comparison to other occupations, according to a study published in January 2020 by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).[59] Researchers at the University of Iowa found that farmers, and others in the agricultural trade, had the highest suicide rate of all occupations from 1992 to 2010, the years covered in a 2017 study.[59] The rate was 3.5 times that of the general population.[59] This echoed a study conducted the previous year by the CDC[60] and another undertaken by the National Rural Health Association (NRHA).[61]

As of April 2023, the suicide rate within the farming community exceeds that of the general population by three and a half times.[61]Most family farmers seem to agree on what led to their plight: government policy. In the years after the New Deal, they say, the United States set a price floor for farmers, essentially ensuring they received a minimum wage for the crops they produced. But the government began rolling back this policy in the 1970s, and now the global market largely determines the price they get for their crops. Big farms can make do with lower prices for crops by increasing their scale; a few cents per gallon of cow's milk adds up if you have thousands of cows.

—Time, November 27, 2019

Environmental issues

[edit]Climate change

[edit]Climate change and agriculture are complexly related processes. In the United States, agriculture is the second largest emitter of greenhouse gases (GHG), behind the energy sector.[62] Direct GHG emissions from the agricultural sector account for 8.4% of total U.S. emissions, but the loss of soil organic carbon through soil erosion indirectly contributes to emissions as well.[63] While agriculture plays a role in propelling climate change, it is also affected by the direct (increase in temperature, change in rainfall, flooding, drought) and secondary (weed, pest, disease pressure, infrastructure damage) consequences of climate change.[62][64] USDA research indicates that these climatic changes will lead to a decline in yield and nutrient density in key crops, as well as decreased livestock productivity.[65][66] Climate change poses unprecedented challenges to U.S. agriculture due to the sensitivity of agricultural productivity and costs to changing climate conditions.[67] Rural communities dependent on agriculture are particularly vulnerable to climate change threats.[64]

The US Global Change Research Program (2017) identified four key areas of concern in the agriculture sector: reduced productivity, degradation of resources, health challenges for people and livestock, and the adaptive capacity of agriculture communities.[64]

Large-scale adaptation and mitigation of these threats relies on changes in farming policy.[63][68]Demographics

[edit]The number of women working in agriculture has risen and the 2002 census of agriculture recorded a 40% increase in the number of female farm workers.[69] Inequality and respect are common issues for these workers, as many have reported that they are not being respected, listened to, or taken seriously due to traditional views of women as housewives and caretakers.[70]

Women may also face resistance when attempting to advance to higher positions. Other issues reported by female farm workers include receiving less pay than their male counterparts and a refusal or reluctance by their employers to offer their female workers the same additional benefits given to male workers such as housing.[71]

As of 2012, there were 44,629 African-American farmers in the United States. The vast majority of African-American farmers were in southern states.[72]

Industry

[edit]Historically, farmland has been owned by small property owners, but as of 2017 institutional investors, including foreign corporations, had been purchasing farmland.[73] In 2013 the largest producer of pork, Smithfield Foods, was bought by a company from China.[73]

As of 2017, only about 4% of farms have sales over $1m, but these farms yield two-thirds of total output.[74] Some of these are large farms have grown organically from private family-owned businesses.[74]

Land ownership laws

[edit]As of 2019, six states—Hawaii, Iowa, Minnesota, Mississippi, North Dakota, and Oklahoma—have laws banning foreign ownership of farmland. Missouri, Ohio, and Oklahoma are looking to introduce bills banning foreign ownership as of 2019.[75][76]

See also

[edit]- Agribusiness

- Electrical energy efficiency on United States farms

- Farmers' suicides in the United States

- Fishing industry in the United States

- Genetic engineering in the United States

- History of African-American agriculture

- History of agriculture in the United States

- List of largest producing countries of agricultural commodities

- Pesticides in the United States

- Poultry farming in the United States

- Soil in the United States

- Urban–rural political divide#United States

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "Latest U.S. Agricultural Trade Data." Archived 2019-10-13 at the Wayback Machine USDA Economic Research Service. Ed. Stephen MacDonald. USDA, 6 Sept. 2018.

- ^ "2017 Census of Agriculture". farmlandinfo.org. 2019-04-11. Archived from the original on 2021-09-04. Retrieved 2021-09-04.

- ^ Hatfield, J., 2012: Agriculture in the Midwest. In: U.S. National Climate Assessment Midwest Technical Input Report Archived 2013-06-21 at the Wayback Machine. J. Winkler, J. Andresen, J. Hatfield, D. Bidwell, and D. Brown, coordinators. Available from the Great Lakes Integrated Sciences and Assessments (GLISA) Center

- ^ Cathy D. Matson, The Economy of Early America, p. 28

- ^ a b c Cronon, William. Changes in the Land : Indians, Colonists, and the Ecology of New England. New York: Hill & Wang, 2003.

- ^ Follett, Richard (April 2016). Plantation kingdom : the American South and its global commodities. JHU Press. ISBN 978-1-4214-1940-4. OCLC 951115501. Retrieved 2021-09-08.

- ^ Wright, Gavin (2003). "Slavery and American Agricultural History". Agricultural History. 77 (4): 536–547. doi:10.1215/00021482-77.4.527. ISSN 0002-1482. JSTOR 3744933. S2CID 247873299.

- ^ Shurtleff, William; Aoyagi, Akiko (2004). History of World Soybean Production and Trade – Part 1. Soyfoods Center, Lafayette, California: Unpublished Manuscript, History of Soybeans and Soyfoods, 1100 B.C. to the 1980s. Archived from the original on 2019-06-03. Retrieved 2014-11-30.

- ^ Pollan, Michael (2007). The omnivore's dilemma: a natural history of four meals. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-303858-0. OCLC 148696764.

- ^ Schapsmeier, Edward L; and Frederick H. Schapsmeier. Encyclopedia of American agricultural history (1975) online

- ^ Cathy D. Matson, The Economy of Early America, p. 27

- ^ "'They're Trying to Wipe Us Off the Map.' Small American Farmers Are Nearing Extinction" Archived 2021-08-10 at the Wayback Machine – Time, November 27, 2019

- ^ Pardey, Philip G.; Alston, Julian M. (2021). "Unpacking the Agricultural Black Box: The Rise and Fall of American Farm Productivity Growth". The Journal of Economic History. 81 (1): 114–155. doi:10.1017/S0022050720000649. ISSN 0022-0507. S2CID 232199950.

- ^ "Tens of millions of acres of cropland lie abandoned, study shows". Washington Post. 2024-06-07. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2024-06-11.

- ^ "Brazil surpasses the USA and resumes the position of largest producer of soy 00 0the planet". Archived from the original on 2021-04-14. Retrieved 2021-02-10.

- ^ "FAOSTAT". www.fao.org. Archived from the original on 2017-05-11. Retrieved 2021-02-10.

- ^ "FAOSTAT". faostat3.fao.org. Archived from the original on 2016-10-19. Retrieved 2015-11-26.

- ^ "United States Crop Rankings – 1997 Production Year". Archived from the original on 2014-08-23. Retrieved 2014-04-01.

- ^ "Crop Values – 2014 Summary" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-09-11. Retrieved 2015-11-26.

- ^ "Chapter IX: Farm Resources, Income, and Expenses" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-04-09. Retrieved 2014-04-01.

- ^ USDA. 2004. 2002 Census of agriculture. United States summary and state data. Vol. 1. Geographic area series. Part 51. AC-02-A-51. 663 pp.

- ^ USDA. 2009. 2007 Census of agriculture. United States summary and state data. Vol. 1. Geographic area series. Part 51. AC-07-A-51. 739 pp.

- ^ USDA. 2014. 2012 Census of agriculture. United States summary and state data. Vol. 1. Geographic area series. Part 51. AC-12-A-51. 695 pp.

- ^ "Appendix A: Glossary" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 18, 2009. Retrieved 2014-04-01.

- ^ "ERS/USDA Briefing Room – Farm Structure: Questions and Answers". Archived from the original on February 9, 2008. Retrieved 2014-04-01.

- ^ "Chapter 3: American Farms" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-08-24. Retrieved 2014-04-01.

- ^ Volkmer, Katrin; Molitor, Whitney Lucas (2019-01-02). "Interventions Addressing Injury among Agricultural Workers: A Systematic Review". Journal of Agromedicine. 24 (1): 26–34. doi:10.1080/1059924X.2018.1536573. ISSN 1059-924X. PMID 30317926. S2CID 52980325.

- ^ Walker, Kristi; Bialik, Kristen (10 January 2019). "Organic farming is on the rise in the U.S." Pew Charitable Trusts. Pew Research Center. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- ^ Willard Cochrane, The Development of American Agriculture: A Historical Analysis (1998)

- ^ Daniel A. Sumner, et al. "Evolution of the economics of agricultural policy." American Journal of Agricultural Economics 92.2 (2010): 403–423 online.

- ^ Murray Benedict, Farm Policies of the United States, 1790-1950: A study of their origins and development (1953).

- ^ "Exemptions to the FLSA". www.dol.gov.

- ^ "Agricultural Safety | NIOSH | CDC". 25 October 2021.

- ^ "USDA ERS - Farm Labor".

- ^ "Search, DRE, Employment & Training Administration (ETA) - U.S. Department of Labor". 19 May 2023.

- ^ Agricultural employment: has the decline ended? Archived 2021-04-16 at the Wayback Machine, Retrieved May 6, 2016

- ^ "Employment by major industry sector". Bls.gov. 2013-12-19. Archived from the original on 2018-05-11. Retrieved 2014-04-01.

- ^ "Extension". Csrees.usda.gov. 2014-03-28. Archived from the original on 2014-03-28. Retrieved 2014-04-01.

- ^ "Agricultural Operations - Overview | Occupational Safety and Health Administration".

- ^ "Crop cultivation Specialization of labour". Agriculture land usa. Retrieved 2024-07-27.

- ^ "NIOSH- Agriculture". United States National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Archived from the original on 9 October 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-10.

- ^ a b c Swanson, Naomi; Tisdale-Pardi, Julie; MacDonald, Leslie; Tiesman, Hope M. (13 May 2013). "Women's Health at Work". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Archived from the original on 18 January 2015. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ^ "NIOSH Pesticide Poisoning MOnitoring Program Protects Farmworkers". Cdc.gov. 2009-07-31. doi:10.26616/NIOSHPUB2012108. Archived from the original on 2013-04-02. Retrieved 2014-04-01.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Calvert, Geoffrey M.; Karnik, Jennifer; Mehler, Louise; Beckman, John; Morrissey, Barbara; Sievert, Jennifer; Barrett, Rosanna; Lackovic, Michelle; Mabee, Laura (Dec 2008). "Acute pesticide poisoning among agricultural workers in the United States, 1998–2005". American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 51 (12): 883–898. doi:10.1002/ajim.20623. ISSN 1097-0274. PMID 18666136. S2CID 9020012.

- ^ a b "NIOSH- Agriculture Injury". United States National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Archived from the original on 28 October 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-10.

- ^ Youth in Agriculture Archived 2019-01-09 at the Wayback Machine, OHSA, accessed January 21, 2014

- ^ NIOSH [2003]. Unpublished analyses of the 1992–2000 Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries Special Research Files provided to NIOSH by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (includes more detailed data than the research file, but excludes data from New York City). Morgantown, WV: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Division of Safety Research, Surveillance and Field Investigations Branch, Special Studies Section. Unpublished database.

- ^ BLS [2000]. Report on the youth labor force. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, pp. 58–67.

- ^ "Guidelines for Children's Agricultural Tasks Demonstrate Effectiveness". Cdc.gov. 2009-07-31. doi:10.26616/NIOSHPUB2011129. Archived from the original on 2014-02-02. Retrieved 2014-04-01.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Deziel, Nicole C.; Friesen, Melissa C.; Hoppin, Jane A.; Hines, Cynthia J.; Thomas, Kent; Freeman, Laura E. Beane (2015-06-01). "A Review of Nonoccupational Pathways for Pesticide Exposure in Women Living in Agricultural Areas". Environmental Health Perspectives. 123 (6): 515–524. doi:10.1289/ehp.1408273. PMC 4455586. PMID 25636067.

- ^ Boedeker, Wolfgang; Watts, Meriel; Clausing, Peter; Marquez, Emily (2020-12-07). "The global distribution of acute unintentional pesticide poisoning: estimations based on a systematic review". BMC Public Health. 20 (1): 1875. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-09939-0. ISSN 1471-2458. PMC 7720593. PMID 33287770. (Retracted, see doi:10.1186/s12889-024-20318-x, PMID 39385166, Retraction Watch)

- ^ Kasner, Edward J.; Prado, Joanne B.; Yost, Michael G.; Fenske, Richard A. (2021-03-15). "Examining the role of wind in human illness due to pesticide drift in Washington state, 2000–2015". Environmental Health. 20 (1): 26. Bibcode:2021EnvHe..20...26K. doi:10.1186/s12940-021-00693-3. ISSN 1476-069X. PMC 7958705. PMID 33722241.

- ^ Habib, R.R.; Fathallah, F.A. (2012). "Migrant women farm workers in the occupational health literature". Work. 41 (1): 4356–4362. doi:10.3233/WOR-2012-0101-4356. PMID 22317389.

- ^ Garcia, Ana M. (2003). "Pesticide Exposure and Women's Health". American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 44 (6): 584–594. doi:10.1002/ajim.10256. PMID 14635235.

- ^ "NIOSH Pesticide Poisoning Monitoring Program Protects Farmworkers". NIOSH. December 2011. Archived from the original on 22 March 2021. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- ^ "NIOSH Grants and Funding – Extramural Research and Training Programs – Training and Research – Agricultural Centers". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2016-03-03. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2016-03-03.

- ^ "Why are America's farmers killing themselves?" – The Guardian, December 11, 2018

- ^ "Farmer suicides" – The Tribune India, November 1, 2021

- ^ a b c Sherman, Lucille (2020-03-09). "Midwest farmers face a crisis. Hundreds are dying by suicide". USA TODAY. Retrieved 2024-07-02.

- ^ "What Five Families Did After Losing The Farm" – The New York Times. February 4, 1987.

- ^ a b Williamson, Elizabeth (19 April 2023). "A Death in Dairyland Spurs a Fight Against a Silent Killer". The New York Times. Loganville, Wisconsin. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 3 January 2024.

- ^ a b Center for Climate and Energy Solutions. 2019. "Science and Impacts".https://www.c2es.org/site/assets/uploads/2019/09/science-and-impacts.pdf

- ^ a b National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition. 2019. Agriculture and Climate Change: Policy Imperatives and Opportunities to Help Producers Meet the Challenge. Washington D.C.

- ^ a b c USGCRP, 2017: Climate Science Special Report: Fourth National Climate Assessment, Volume II[Wuebbles, D.J., D.W. Fahey, K.A. Hibbard, D.J. Dokken, B.C. Stewart, and T.K. Maycock (eds.)]. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, US, 470 pp, doi:10.7930/J0J964J6.

- ^ Evich, Helena Bottemiller (2019-09-19). "Senate Democrats release list of climate studies buried by Trump administration". POLITICO. Retrieved 2019-10-25.

- ^ US Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition and Forestry. "Peer-Reviewed Research on Climate Change by USDA Authors, January 2017-August 2019". Politico. Retrieved 2019-10-25.

- ^ USDA Agricultural Research Service, Climate Change Program Office (2013). "Climate Change and Agriculture in the United States: Effects and Adaptation" (PDF). United States Department of Agriculture. USDA Technical Bulletin 1935. pp. 1–2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2022-05-13. Retrieved 2019-10-15.

- ^ Carlisle, Liz, Maywa Montenegro de Wit, Marcia S. DeLonge, Alastair Iles, Adam Calo, Christy Getz, Joanna Ory, Katherine Munden-Dixon, Ryan Galt, Brett Melone, Reggie Knox, and Daniel Press. 2019. "Transitioning to Sustainable Agriculture Requires Growing and Sustaining an Ecologically Skilled Workforce." Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2019.00096

- ^ Albright, Carmen (2006). "Who's Running The Farm?: Changes and characteristics of Arkansas women in Agriculture". American Agricultural Economics Association: 1315–1322.

- ^ Jones, L. (2015). "North Carolina's Farm Women: Plowing around Obstacles". University of Georgia Press.

- ^ Golichenko, M.; Sarang, A. (2013). "Farm labor, reproductive justice: Migrant women farmworkers in the US". Health and Human Rights.

- ^ "USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service – Highlights" (PDF). USDA National Agricultural Statistics. United States Department of Agriculture. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 December 2016. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- ^ a b "Who really owns American farmland? – The New Food Economy". New Food Economy. 2017-07-31. Archived from the original on 2019-06-18. Retrieved 2019-06-18.

- ^ a b Good, Keith (2017-11-08). "Crop Choices, Farm Size: Changes in a Time of Low Corn and Soybean Prices • Farm Policy News". Farm Policy News. Archived from the original on 2019-06-18. Retrieved 2019-06-18.

- ^ "As Foreign Investment in U.S. Farmland Grows, Efforts to Ban and Limit the Increase Mount". Successful Farming. June 6, 2019. Archived from the original on July 25, 2020. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- ^ Reporting, Erin McKinstry/For the Midwest Center for Investigative (June 22, 2017). "Regulation on foreign ownership of agricultural land: A state-by-state breakdown". Investigate Midwest. Archived from the original on June 8, 2020. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

Cited sources

[edit]- Mbow, Cheikh; Rosenzweig; Barioni, Luis .G.; Benton, Tim .G. (2019). "Food security". In Shukla, P.R.; Skea, J.; Buendia, E. Calvo; Masson-Delmotte, V. (eds.). Climate Change and Land: an IPCC special report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems. IPCC.

Further reading

[edit]- Cochrane, Willard. The Development of American Agriculture: A Historical Analysis (1998)

- Conkin, Paul. A Revolution Down on the Farm: The Transformation of American Agriculture since 1929 (2008)

- Gardner, Bruce L. (2002). American Agriculture in the Twentieth Century: How It Flourished and What It Cost. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-00748-4.

- Hurt, R. Douglas. A Companion to American Agricultural History (Wiley-Blackwell, 2022)

- Lauck, Jon. American agriculture and the problem of monopoly: the political economy of grain belt farming, 1953-1980 (U of Nebraska Press, 2000).

- Riney-Kehrberg, Pamela. ed. The Routledge History of Rural America (2018)

- Schapsmeier, Edward L; and Frederick H. Schapsmeier. Encyclopedia of American agricultural history (1975) online

- Schmidt, Louis Bernard, and Earle Dudley Ross, eds. Readings in the economic history of American agriculture (Macmillan, 1925) excerpts from scholarly studies, colonial era to 1920s. online.

- Spitze, Robert G. F.; Harold G. Halcrow; Joyce E. Allen-Smith (1994). Food and Agricultural Policy. Mcgraw-Hill College. ISBN 0-07-025800-7.

- Winterbottom, Jo; Huffstutter, P. J. (Feb. 2015). Rent walkouts point to strains in U.S. farm economy, Reuters