Ted Turner

Ted Turner | |

|---|---|

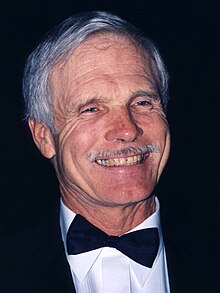

Turner in 2015 | |

| Born | Robert Edward Turner III November 19, 1938 Cincinnati, Ohio, U.S. |

| Alma mater | Brown University |

| Occupation(s) | Entrepreneur, television producer, media proprietor, philanthropist |

| Years active | 1960–present |

| Known for |

|

| Spouses | Julia Gale Nye

(m. 1960; div. 1964)Jane Shirley Smith

(m. 1965; div. 1988) |

| Children | 5 |

| Website | tedturner |

| Signature | |

| |

Robert Edward Turner III (born November 19, 1938) is an American entrepreneur, television producer, media proprietor, and philanthropist. He founded the Cable News Network (CNN), the first 24-hour cable news channel. In addition, he founded WTBS, which pioneered the superstation concept in cable television, as well as TV networks TBS and TNT.

As a philanthropist, he gave $1 billion to create the United Nations Foundation, a public charity to broaden U.S. support for the UN. Turner serves as Chairman of the United Nations Foundation board of directors.[1] Additionally, in 2001, Turner co-founded the Nuclear Threat Initiative with US Senator Sam Nunn (D-GA). NTI is a non-partisan organization dedicated to reducing global reliance on, and preventing the proliferation of nuclear, chemical, and biological weapons. He currently serves as co-chairman of the board of directors.

Turner's media empire began with his father's billboard business, Turner Outdoor Advertising, which he took over in March 1963 after his father's suicide.[2] It was worth $1 million. His purchase of an Atlanta UHF station in 1970 began the Turner Broadcasting System. CNN revolutionized news media, covering the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster in 1986 and the Persian Gulf War in 1991. Turner turned the Atlanta Braves baseball team into a nationally popular franchise (including winning the 1995 World Series under his ownership), and launched the charitable Goodwill Games. He helped revive interest in professional wrestling by purchasing Jim Crockett Promotions which was then rebranded as World Championship Wrestling (WCW).

Turner's penchant for controversial statements earned him the nicknames "The Mouth of the South" and "Captain Outrageous".[3][4] Turner has also devoted his assets to environmental causes. He was the largest private landowner in the United States until John C. Malone surpassed him in 2011.[5][6] He uses much of his land for ranches to re-popularize bison meat (for his Ted's Montana Grill chain) and has amassed the largest herd in the world. He also created the environmental-themed animated series Captain Planet and the Planeteers.[7]

Early life

Turner was born on November 19, 1938, in Cincinnati, Ohio,[8] the son of Florence (née Rooney) and Robert Edward Turner II, a billboard magnate.[9] When he was nine, his family moved to Savannah, Georgia, and raised him as an Episcopalian.[10] He attended The McCallie School, a private boys' preparatory school in Chattanooga, Tennessee.

Turner attended Brown University and was vice-president of the Brown Debating Union and captain of the sailing team. He became a member of Kappa Sigma. Turner initially majored in classics. His father wrote saying that this choice made him "appalled, even horrified", and that he "almost puked".[11] Turner later changed his major to economics, but before receiving a degree, he was expelled for having a female student in his dormitory room.[12] Turner was awarded an honorary B.A. from Brown University in November 1989 when he returned to campus to give the keynote address for the National Association of College Broadcasters second annual conference.

Expelled from Brown just as tensions in Vietnam were beginning to heat up, Turner joined the United States Coast Guard Reserve in order to fill his service obligation before he ended up getting drafted. Honored by the United States Navy Memorial with its Lone Sailor Award in 2013, Turner told The Washington Post, "I liked boats", and ended up getting "deployed to some pretty sweet places – Charleston and Fort Lauderdale."[13]

Business career

WTBS

After leaving Brown University, Turner returned to the South in late 1960 to become general manager of the Macon, Georgia, branch of his father's business. Following his father's suicide in March 1963, Turner became president and chief executive of Turner Advertising Company when he was 24 and turned the firm into a global enterprise. He joined the Young Republicans, saying he "felt at ease among these budding conservatives and was merely following in [his father]'s far-right footsteps", according to It Ain't as Easy as It Looks.[2]

During the Vietnam War era, Turner's business prospered; it had "virtual monopolies in Savannah, Macon, Columbus, and Charleston" and was the "largest outdoor advertising company in the Southeast", according to It Ain't as Easy as It Looks. The book observed that Turner "discovered his father had sheltered a substantial amount of taxable income over the years by personally lending it back to the company" and "discovered that the billboard business could be a gold mine, a tax-depreciable revenue stream that threw off enormous amounts of cash with almost no capital investment".[14]

In the late 1960s Turner began buying several Southern radio stations.[15] In 1969, he sold his radio stations to buy a struggling television station in Atlanta, UHF Channel 17 WJRJ (now WPCH).[16] At the time, UHF stations did well only in markets without VHF stations, like Fresno, California, or in markets with only one station on VHF. Independent UHF stations were not ratings winners or that profitable even in larger markets, but Turner concluded that this would change as people wanted more than several choices. He changed the call sign to WTCG, erroneously claimed to have stood for "Watch This Channel Grow" but in actuality stood for Turner Communications Group.[17] Initially, the station ran old movies from prior decades, along with theatrical cartoons and bygone sitcoms and drama programs. As a better syndicated product fell off the VHF stations, Turner would acquire it for his station at a very low price. WTCG ran mostly second- and even third-hand programming of the time, including fare such as Gilligan's Island, I Love Lucy, Star Trek, Hazel, and Bugs Bunny. Other low-cost content included humorist Bill Tush reading the news at 3 a.m., prompting Turner to jokingly comment that, "we have a 100% share at this time". Tush once delivered the news with his "co-anchor" Rex, a German Shepherd. The dog (who belonged to an associate) was shown next to Tush on set, wearing a shirt and tie while eating a peanut butter sandwich. Rex appeared only on one episode, but a myth grew where many people thought the dog was a nightly guest.[18] By 1972, WTCG had acquired the rights to telecast Atlanta Braves and Atlanta Hawks games.[19] Turner would go on to purchase UHF Channel 36 WRET (now WCNC) in Charlotte, North Carolina, and ran it with a format similar to WTCG.[citation needed]

In 1976, the Federal Communications Commission allowed WTCG to use a satellite to transmit content to local cable TV providers around the nation. On December 17, 1976, the rechristened WTCG-TV Super-Station began to broadcast old movies, situation comedy reruns, cartoons, and sports nationwide to cable-TV subscribers.[20] As cable systems developed, many carried his station to free their schedules, which increased his viewers and advertising. The number of subscribers eventually reached 2 million and Turner's net worth rose to $100 million. He bought a 5,000-acre (2,000 ha) plantation in Jacksonboro, South Carolina, for $2 million.[21]

In 1976, Turner bought the Atlanta Braves, and in 1977, he bought the Atlanta Hawks, partially to provide programming for WTCG.[22][23] Using the rechristened WTBS superstation's status to broadcast Braves games into nearly every home in North America, Turner turned the Braves into a household name even before their run of success in the 1990s and early 2000s.[24] At one point, he suggested to pitcher Andy Messersmith, who wore number 17, that he change his surname to "Channel" to promote the television station.[25]

In 1978, Turner struck a deal with a student-operated radio station at MIT, Technology Broadcasting System (now WMBR), to obtain the rights to the WTBS call sign for $50,000. Such a move allowed Turner to strengthen the branding of his "Super-Station" using the initials TBS. Turner Communications Group was renamed Turner Broadcasting System and WTCG was renamed WTBS.[26]

In 1986, Turner founded the Goodwill Games with the goal of easing tensions between capitalist and communist countries. Broadcasting the events of these games also provided his superstation the ability to provide Olympic-style sports programming.[27]

Turner Field, first used for the 1996 Summer Olympics as Centennial Olympic Stadium and then converted into a baseball-only facility for the Braves, was named after him.[28]

CNN

In 1978, he contacted media executive Reese Schonfeld with his plans to launch a 24-hour news channel (Schonfeld had previously approached Turner with the same proposition in 1977 but was rebuffed).[29] Schonfeld responded that it could be done with a staff of 300 if they used an all electronic newsroom and satellites for all transmissions.[29] It would require an initial investment of $15 million–$20 million and several million dollars per month to operate.[29]

In 1979, Turner sold his North Carolina station, WRET, to fund the transaction and established its headquarters in lower-cost, non-union Atlanta.[29] Schonfeld was appointed first president and chief executive of the then-named Cable News Network (CNN).[29] CNN hired Jim Kitchell, former general manager of news at NBC as vice president of production and operations; Sam Zelman as vice president of news and executive producer; Bill MacPhail as head of sports, Ted Kavanau as director of personnel, and Burt Reinhardt as vice president of the network.[29] In 1982, Schonfeld was succeeded as CEO by Turner after a dispute over Schonfeld's firing of Sandi Freeman; and was succeeded as president by CNN's executive vice president, Burt Reinhardt.[30]

Turner Doomsday Video

Turner famously stated before the network debuted: "We won't be signing off until the world ends. We'll be on, and we will cover the end of the world, live, and that will be our last event... we'll play the National Anthem only one time, on the 1st of June [the network's debut on June 1, 1980], and when the end of the world comes, we'll play 'Nearer, My God, to Thee' before we sign off." Reportedly, Turner plans to make good on that promise. He commissioned a video recording of a military marching band playing the hymn. Turner has sometimes played the tape for reporters, noting the reason he made it. In 2015, the video was found in CNN's database and leaked. The video was tagged in the database as "[Hold for release] till end of world confirmed".[31]

Other ventures

| Part of a series on |

| Professional wrestling |

|---|

|

In 1981, Turner Broadcasting System acquired Brut Productions from Faberge Inc.[32]

After a failed attempt to acquire CBS, Turner purchased the film studio MGM/UA Entertainment Co. from Kirk Kerkorian in 1986 for $1.5 billion.[33] Following the acquisition, Turner had amassed enormous debt and sold parts of the acquisition; Kerkorian bought back MGM/UA Entertainment. The MGM/UA Studio lot in Culver City was sold to Lorimar/Telepictures. Turner kept MGM's pre-May 1986 and pre-merger film and television library.[34][35]

Turner Entertainment was established in August 1986 to oversee film and television properties owned by Turner thanks to the deal with Kerkorian.[citation needed]

Having now acquired MGM's library of 2,200 films made before 1986, Turner had them syndicated on his nationwide television stations.[33] When broadcasting their older films, he aired colorized versions of ones originally shot in black-and-white.[36] Opposition arose from cinephiles, actors, and directors to Turner's colorization efforts. Film critic Roger Ebert wrote on Turner's broadcasting of a colorized Casablanca, "that will be one of the saddest days in the history of the movies. It is sad because it demonstrates that there is no movie that Turner will spare, no classic however great that is safe from the vulgarity of his computerized graffiti gangs."[37] Thanks in part to Turner's colorization, the Library of Congress established the National Film Registry with the aim to preserve American films in their original format.[38]

In 1988, Turner purchased Jim Crockett Promotions which he renamed World Championship Wrestling (WCW) which became the main competitor to Vince McMahon's World Wrestling Federation (WWF). This rivalry became known as the Monday Night War, and would last throughout the 1990s. In 2001, under AOL Time Warner, WCW was sold to the WWF.[39]

Also in 1988, he introduced Turner Network Television (TNT) with Gone with the Wind. TNT, initially showing older movies and television shows, added original programs and newer reruns. Turner would later create Turner Classic Movies (TCM) in 1994, airing Turner's pre-1986 MGM library of films alongside those of Warner Bros. made before 1950, though it has expanded its library since.[citation needed]

In 1989, Turner created the Turner Tomorrow Fellowship for fiction offering positive solutions to global problems. The winner, from 2500 entries worldwide, was Daniel Quinn's Ishmael.[citation needed]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

In 1990, he created the Turner Foundation, which focuses on philanthropic grants concerning issues pertaining to the environment and overpopulation. In the same year he created Captain Planet, an environmental superhero. Turner produced the television series Captain Planet and the Planeteers and its later sequel series with Captain Planet as the featured character.[40]

In 1992, the pre-May 1986 MGM library, which also included Warner Bros. properties including the early Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies libraries and also the Fleischer Studios and Famous Studios Popeye cartoons from Paramount (and then United Artists), became the core of Cartoon Network. A year before, Turner's companies purchased Hanna-Barbera Productions (whose longtime parent, Taft/Great American Broadcasting, had been headquartered in Turner's original hometown of Cincinnati), beating out several other bidders including MCA Inc. (whose subsidiaries included Universal Pictures and Universal Destinations & Experiences) and Hallmark Cards. With the 1996 Time Warner merger, the channel's archives gained the later Warner Bros. cartoon library as well as other Time Warner-owned cartoons.[citation needed]

In 1993, Turner and Russian journalist Eduard Sagalajev founded the Moscow Independent Broadcasting Corporation (MIBC). This corporation operated the sixth frequency in Russian television and founded the Russian channel TV-6.[41] The company was later purchased by Russian businessman Boris Berezovsky and an unknown group of private persons. In 2007 the license for TV-6 had expired and there was no application for renewal.[citation needed]

Time Warner merger

Turner Broadcasting System merged with Time Warner Entertainment on October 10, 1996, with Turner as vice chairman and head of Time Warner Entertainment and Turner's cable networks division.[42] Turner was dropped as head of cable networks by CEO Gerald Levin but remained as Vice Chairman of Time Warner Entertainment. He would be succeeded in March 2001 as head of Turner Broadcasting by Jamie Kellner, who was also greatly responsible for cancelling WCW's television contracts on networks which Turner previously ran.[43][44][45] He resigned as AOL Time Warner vice chairman in 2003 and then from the Time Warner board of directors in 2006.[46][47]

On January 11, 2001, Time Warner Entertainment was purchased by America Online (AOL) to become AOL Time Warner,[48] a merger which Turner initially supported.[49] However, the burst of the dot-com bubble hurt the growth and profitability of the AOL division, which in turn dragged down the combined company's performance and stock price. At a board meeting in fall 2001, Turner's outburst against AOL Time Warner CEO Gerald Levin eventually led to Levin's announced resignation effective in early 2002, being replaced by Richard Parsons.[50] In contrast to Levin, who as CEO isolated Turner from important company matters, Parsons invited Turner back to provide strategic advice, although Turner never received an operational role that he sought.[51] The company dropped "AOL" from its name in October 2003. In December 2009, AOL was spun off from the Time Warner conglomerate as a separate company.[citation needed]

Turner was Time Warner's biggest individual shareholder.[50] It is estimated he lost as much as $7 billion when the stock collapsed in the wake of the merger.[52] When asked about buying back his former assets, he replied that he "can't afford them now".[53] In June 2014, Rupert Murdoch's 21st Century Fox made a bid for the company valuing it at $80 billion. The Time Warner board rejected the offer and it was formally withdrawn on August 5, 2014.[54]

Rivalry with Murdoch

Turner had a long-running feud with fellow cable magnate Rupert Murdoch for years. This originated in 1983 when a Murdoch-sponsored yacht collided with the yacht skippered by Turner, Condor, during the Sydney to Hobart Yacht Race, causing it to run aground 6.2 miles (10.0 km) from the finish line. At the post-race dinner, a drunken Turner verbally assaulted Murdoch, afterward challenging him to a televised fistfight in Las Vegas.[55]

Murdoch's Fox News, established in 1996, became a rival to Turner's CNN, a channel that Murdoch regarded with disdain for its "liberal slant" in news coverage. Time Warner declined to carry it on their New York City cable network in response, who in the midst of a merger, Turner said would "squash Rupert Murdoch like a bug."[56]

In 2003, Turner challenged Murdoch to another fistfight, and later on accused Murdoch of being a "warmonger" for his support and backing of President George W. Bush's invasion of Iraq.[57][58]

However, revealing in an interview with Variety in 2019, Turner said he and Murdoch have since made amends.[59]

Atlanta Braves

| Ted Turner | |

|---|---|

| Atlanta Braves – No. 27 | |

| Manager | |

| Born: November 19, 1938 Cincinnati, Ohio | |

| MLB debut | |

| May 11, 1977, for the Atlanta Braves | |

| Last MLB appearance | |

| May 11, 1977, for the Atlanta Braves | |

| MLB statistics | |

| Games | 1 |

| Win–loss record | 0–1 |

| Winning % | .000 |

| Managerial record at Baseball Reference | |

| Teams | |

| |

For most of his first decade as owner of the Braves, Turner was a very hands-on owner. This peaked in 1977, his second year as owner.[citation needed]

Turner was suspended for one year by Commissioner of Baseball Bowie Kuhn on January 3, 1977, for his actions while pursuing the signing of free agent outfielder Gary Matthews from the San Francisco Giants. Matthews signed a five-year, $1.875 million contract with the Braves on November 18, 1976. Kuhn's actions stemmed from remarks made by Turner to then-Giants owner Bob Lurie during the 1976 World Series. In addition, the Braves were also stripped of their first-round selections in the June 1978 draft of high school and college players.[60] Turner, however, successfully appealed the suspension and Kuhn relented and reinstated the draft selections, one of which would turn out to be Bob Horner from Arizona State University.[61]

On May 11, 1977, with the team mired in a 16-game losing streak, Turner sent manager Dave Bristol on a 10-day "scouting trip" and Turner himself took over as interim manager – the first owner/manager in the majors since Connie Mack. He ran the team for one game (a loss to the Pittsburgh Pirates)[62] before National League president Chub Feeney ordered him to stop running the team. Feeney cited major league rules which bar managers and players from owning stock in their clubs. Turner appealed to Commissioner of Baseball Bowie Kuhn, and showed up to manage the Braves when they returned home. However, Kuhn turned down the appeal, citing Turner's "lack of familiarity with game operations."[63]

In the mid-1980s Turner began leaving day-to-day operations to the baseball operations staff, and the team (still under Turner's ownership) won the 1995 World Series.

The Atlanta Braves were sold by Time Warner (which had assumed control after the merger with Turner Broadcasting System) to Liberty Media in 2007.[64]

Awards and honors

- Lifetime Achievement – Sports (2014)

- Lifetime Achievement – News & Documentary (2015)

Sports

- 1995: World Series champion (as owner of the Atlanta Braves)

- 1996: Atlanta Braves home ballpark (1996–2016) named Turner Field

- 2004: Commemorative banner at State Farm Arena honoring his tenure as owner of the Atlanta Hawks[65]

Media

- 1984: Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement[66]

- 1989: Paul White Award, Radio Television Digital News Association[67]

- 1990: Walter Cronkite Award for Excellence in Journalism.[68]

- 1991: Time magazine's Man of the Year.

- 1997: Peabody Award winner

- 1999: Edison Achievement Award for his commitment to innovation throughout his career

- 2000: Edward R. Murrow Award for Lifetime Achievement in Communication[69]

Halls of Fame

- 1991: Television Hall of Fame inductee

- 2004: Star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame

Organizational

- 1991: Audubon medal from the National Audubon Society[70]

- 2001: Albert Schweitzer Gold Medal for Humanitarianism

- 2010: Georgia Trustee, an honor given by the Georgia Historical Society, in conjunction with the Governor of Georgia[71]

- 2013: Lone Sailor Award, which recognizes Navy, Marine and Coast Guard veterans who have distinguished themselves in their civilian careers (Turner is a Coast Guard veteran).[72]

Politics

On September 19, 2006, in a Reuters Newsmaker conference, Turner said of Iran's nuclear position: "They're a sovereign state. We have 28,000. Why can't they have 10? We don't say anything about Israel—they've got 100 of them approximately—or India or Pakistan or Russia."[73]

A proponent of healthcare reform bills, Turner has said: "We’re the only first-world country that doesn't have universal healthcare and it's a disgrace."[74]

In 2010, during the wake of both the devastating Deepwater Horizon environmental disaster and the Upper Big Branch Mine disaster that killed 29 miners in West Virginia, Turner stated on CNN that "I'm just wondering if God is telling us he doesn't want to drill offshore. And right before that, we had that coal mine disaster in West Virginia where we lost 29 miners ... Maybe the Lord's tired of having the mountains of West Virginia, the tops knocked off of them so they may get more coal. I think maybe we ought to just leave the coal in the ground and go with solar and wind power and geothermals ..."[75]

Turner endorsed Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton in the run-up for the 2016 U.S. presidential election.[76] In 2018 he revealed he had once considered a run for president when he was married to Jane Fonda, who told him she would leave him if he did.[77]

Curbing population growth

Along with advocating for clean water and improved stewardship of the land, Turner established the Turner Foundation to address ways to curb population growth.[78] Turner has put $125 million of his own money into the foundation and has set aside $6 million per year to address population growth rates. Addressing the issue at a Montana gathering in 1996 he said "I'm not talking about getting rid of anybody here, I've got 5 children myself." He went on to discuss hunger and poverty and ways to address those issues.[79]

In 2009 Turner met with other business moguls to include Oprah Winfrey, Bill Gates, George Soros and David Rockefeller to address issues ranging from the environment to healthcare. The group also addressed population growth with discussion of vaccines and immunization efforts being criticized due to the perception that decision making and public policy could be directed by a handful of elites. Although no formal statement was released, the event was covered by Paul Harris for The Guardian.[80]

Controversial comments

Turner once called observers of Ash Wednesday "Jesus freaks", though he apologized,[81] and dubbed opponents of abortion "bozos".[81]

In 1999, Turner made a joke about Polish mine detectors when asked about Pope John Paul II. After a harsh response from the Polish deputy foreign minister Radek Sikorski, Turner apologized.[82]

In 2002, Turner accused Israel of terror: "The Palestinians are fighting with human suicide bombers, that's all they have. The Israelis ... they've got one of the most powerful military machines in the world. The Palestinians have nothing. So who are the terrorists? I would make a case that both sides are involved in terrorism." He apologized for that and the remarks in 2011 about the 9/11 hijackers, but also defended himself: "Look, I'm a very good thinker, but I sometimes grab the wrong word ... I mean, I don't type my speeches, then sit up there and read them off the teleprompter, you know. I wing it."[83]

Also in 2008, Turner asserted on PBS's Charlie Rose television program that if steps are not taken to address global warming, most people would die and "the rest of us will be cannibals". Turner also said in the interview that he advocated Americans having no more than two children. In 2010, he stated that China's one-child policy should be implemented.[84]

Turner Enterprises

Turner Enterprises, Inc. (TEI) is a private American company that was founded in 1976 and manages the business interests, land holdings and investments of Ted Turner,[85] including the oversight of Turner's 24 properties across the United States and Argentina. At two million acres of personal and ranch land, Turner is the second-largest landowner in North America.[86] He owned 19 ranches – 16 in the western U.S. and three in Argentina.[86] In January 2016, the Osage Nation bought Turner's 43,000 acre (170 km2) Bluestem Ranch in Osage County, Oklahoma. Turner had purchased the property in 2001 primarily to raise bison.[citation needed]

Through Turner Enterprises, he owns ranches in Colorado, Kansas, Montana, Nebraska, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and South Dakota.[87][88] Totaling 1,910,585 acres (7,731.86 km2), his land-holdings across America make Turner one of the largest individual landowners in North America (by acreage).[88]

TEI ranches are primarily used for bison ranching. His bison herd is present on 15, and at approximately 51,000 is the largest private herd in the world.[86] The company's mission statement is "To manage Turner lands in an economically sustainable and ecologically sensitive manner while promoting the conservation of native species."[86] Other important wildlife species on the property include whitetail deer, wild turkey and bobwhite quail.[89] In addition to bison ranching, TEI ranches are also used for commercial fishing and hunting, as well as limited sustainable timber harvesting, as well as eco-tourism on the New Mexico ranches.[86] His biggest ranch is Vermejo Park Ranch in New Mexico. At 920 square miles (2,400 km2), it is the largest privately owned, contiguous tract of land in the United States.[90]

TEI works closely with Turner's philanthropic and charitable interests, including the founding and ongoing operations of the United Nations Foundation, Nuclear Threat Initiative, Turner Foundation,[91] Planet Foundation],[92] and the Turner Endangered Species Fund.[85] Turner Enterprises is headquartered in the Turner Building (formerly the Bona Allen Office Building) in Atlanta, Georgia, also home to the Ted's Montana Grill restaurant chain, Ted Turner Reserves[93] and Turner Renewable Energy.[94][95] In 2011, Ted Turner and TEI completed construction of a 25-panel solar array in the company's parking lot, which provides solar power to the Turner Building and its businesses[96]

Chaired by Turner, TEI's executive leadership also includes CEO & President S. Taylor Glover.[97]

Personal life

Turner has been married and divorced three times: to Judy Nye (1960–1964), Jane Shirley Smith (1965–1988), and actress Jane Fonda (1991–2001). He has five children.[98] In a television interview with Piers Morgan on May 3, 2012, Turner said he had four girlfriends, which he acknowledged was complicated but nonetheless easier than being married.[99] One of Turner's children, Robert Edward "Teddy" Turner IV, announced on January 23, 2013, that he intended to run in the South Carolina Republican primary for the open Congressional seat vacated by Tim Scott who was appointed to the US Senate.[100] Turner's son came in 4th, receiving 7.90% of the vote.[101]

In 2010, Turner joined Warren Buffett's and Bill Gates's The Giving Pledge, vowing to donate the majority of his fortune to charity upon his death.[102]

In the 1993 biography It Ain't As Easy as It Looks by Porter Bibb, Turner discussed his use of lithium and struggles with mental illness. The 1981 biography Lead, Follow or Get Out of the Way by Christian Williams chronicles the founding of CNN.[103] In 2008, Turner wrote Call Me Ted, which documents his career and personal life.[104]

In an interview on CBS Sunday Morning in 2018, Turner revealed his diagnosis of Lewy body dementia.[105]

Sailing

| Sailing career | |

|---|---|

| Club | |

| College team | |

When Turner was 26, he entered sailing competitions at the Savannah Yacht Club and competed in Olympic trials in 1964.[106] He first attempted to win the America's Cup in 1974, losing in the defender's trials, aboard 12 Metre class yacht US–25 Mariner.[107] Turner was defeated by Ted Hood aboard US–26 Courageous.

Turner was asked to join the 1977 America's Cup defense syndicate formed by Hood and Lee Loomis for the New York Yacht Club. That group still owned the Courageous but decided to design and construct a new 12 Metre - US–28 Independence - to defend the 1974 America's Cup victory. However, in the trials, with Turner as skipper aboard the 3-year-old Courageous proved to be the faster than Hood and Independence [108] and was selected to race in the 1977 races.

From 13 to 18 September 1977 Courageous, with Turner in command, defeated the challenger Australia, skippered by Noel Robins, in a four-race sweep.[109] Courageous' greatest winning margin out of all four races was 2 minutes and 23 seconds.[109][110]

In the 1979 Fastnet Race, in a storm that killed 15 participants, he skippered the S&S-designed[111] 61-footer Tenacious to a corrected-time victory.[112]

Turner appeared on the cover of Sports Illustrated on July 4, 1977,[113] after winning 1977 America's Cup.[114] Turner was inducted into the America's Cup Hall of Fame in 1993,[115] and the National Sailing Hall of Fame in 2011.[116]

Legacy

Turner has been regarded as one of the entrepreneurs who transformed the cable industry and being referred to as "Alexander the Great of broadcasting":[117]

While Turner has been described as a "valiant liberator" and cast the networks as oppressive scoundrels, in content his programming fell short of inspiring. His network was built on sitcom reruns, old movies, cartoons, and Atlanta Braves games. He found an audience for classics of a bygone time, along with slightly down-market content like professional wrestling. Nonetheless, he would find glorious terms even for retreads and junk, claiming to be pulling America back to television's golden age: "I want to get it back to the principles" he once said, "that made us good." Nostalgic, Manichean, and boot-strappy: like programmer, like programming[117]

The cable industry boomed in the late 1970s and early 1980s, as nearly a dozen cable networks launched based on the Turner model. They include much of what we now consider the staples of cable TV, including ESPN, MTV, Bravo, Showtime, BET, the Discovery Channel, and the Weather Channel. Those are the better-known channels only by virtue of having survived; others, such as ARTS, CBS Cable, and the Satellite News Channel, folded or were acquired by other companies[117]

Bob Hope, who is co-owner and president of Hope-Beckham, an independent agency based in Atlanta that previously worked for Turner in his networks, has described that "Ted Turner was special. His vision and his determination and his unwillingness to quit were infectious. He was willing to start small and had the persistence and patience to make his ideas grow".[118] Hope also further reiterated that "In some ways, he was outrageous, but in most ways he was remarkable. He had great passion for doing what was right for the world. He stated his dream of using communication to bring peace, to tell both sides of any story, that 'one man's terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter.' If he could get people to understand each other, there would be no wars. His vision was bold and infectious. His Goodwill Games, his creation of the UN Foundation, and his approach to news on the original CNN were passions for peace".[118]

Professional wrestling promoter and former Senior Vice President of WCW second in charge after Turner, Eric Bischoff praised Turner claiming "He was an inspirational leader, he was a risk taker, he appreciated people who took risks, he was not afraid of failure while most people are. Ted was not afraid to fail, he was more afraid of not trying and not conquering that next horizon.”[119]

On June 24, 1999, Vince McMahon stated on Late Night with Conan O'Brien: "All I'll say about Ted is he's a son-of-a-bitch, other than that, he's probably not a bad guy, but I don't like him at all".[120] Later in 2021, when asked about the upstart AEW in comparison to Turner's WCW, McMahon dismissed AEW, stating that "it certainly is not a situation where 'rising tides' because that was when Ted Turner was coming after us with all of Time Warner's assets as well".[121]

In 2010 Turner was named a Georgia Trustee, an honor given by the Georgia Historical Society, in conjunction with the Governor of Georgia, to individuals whose accomplishments and community service reflect the ideals of the founding body of Trustees, which governed the Georgia colony from 1732 to 1752.

References

- ^ "United Nations Foundation | Helping the UN build a better world". Unfoundation.org. Retrieved October 21, 2021.

- ^ a b Porter Bibb (1996). Ted Turner: It Ain't as Easy as It Looks: The Amazing Story of CNN. Virgin Books. pp. 55–56. ISBN 0-86369-892-1.

- ^ Porter Bibb (1996). Ted Turner: It Ain't As Easy as It Looks: The Amazing Story of CNN. Virgin Books. pp. 138, 272, 283, 442. ISBN 0-86369-892-1.

- ^ Koepp, Stephen (April 12, 2005). "Captain Outrageous Opens Fire". Time. Archived from the original on October 29, 2010.

- ^ Doyle, Leonard (December 1, 2007). "Turner becomes largest private landowner in US – Americas, World". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on May 17, 2009. Retrieved March 29, 2009.

- ^ Seelye, Katharine Q. (January 28, 2011). "For Land Barons, Acres by the Millions". The New York Times.

- ^ Eve M. Kahn (March 3, 1991). "Television; Cartoons for a Small Planet". New York Times. Retrieved March 9, 2015.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica. "Ted Turner – Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Retrieved March 24, 2010.

- ^ "Ted Turner Biography (1938–)". Film Reference. Retrieved March 24, 2010.

- ^ Ted Turner: A Biography: A Biography. Abc-Clio. 2009. ISBN 9780313350436.

- ^ "This is my son. He speaks Greek". Lettersofnote. July 25, 2012. Archived from the original on July 27, 2012. Retrieved July 26, 2012.

- ^ Porter Bibb (1996). Ted Turner: It Ain't As Easy as It Looks: The Amazing Story of CNN. Virgin Books. pp. 26–33. ISBN 0-86369-892-1.

- ^ "Ted Turner, swaggering billionaire humbled by 'Lone Sailor' prize for long-ago Coast Guard stint". The Washington Post. September 19, 2013.

- ^ Bibb, Porter (1993). It Ain't as Easy as it Looks: Ted Turner's Amazing Story. Crown Publishers. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-517-59322-6.

- ^ O'Connor, Michael (2009). "5". Ted Turner: A Biography. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-35043-6.

- ^ "Merger is proposed by Rice, Turner". Broadcasting. Broadcasting Publications, Inc. July 14, 1969.

- ^ "For the Record". Broadcasting. Broadcasting Publications, Inc. April 13, 1970.

- ^ "Bill Tush's 30-year TV career began the lucky moment he stopped by Channel 17 for a job". Saporta Report. saportareport.com. May 21, 2012. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ "Program Briefs: Hawks roost beside Braves". Broadcasting. Broadcasting Publications, Inc. October 16, 1972.

- ^ "Ted Turner." Encyclopedia of World Biography, 2nd ed., vol. 15, Gale, 2004, pp. 355–357.

- ^ Endicott, Eve (1993). Land Conservation Through Public/Private Partnerships. Island Press. ISBN 978-1-61091-349-2.

- ^ "Yachtsman Turner Purchases Braves". The New York Times. January 7, 1976.

- ^ Hart, Micah (November 30, 2004). "Hawks Raise Banner To Honor Turner". NBA.com. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- ^ Bagbey, Jordan (December 16, 2009). "Call Me Owner: Why the Braves Need Ted Turner Back". Bleacher Report. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- ^ Gary Caruso (March 20, 2008). "Messersmith: The game's first free agent". MLB.com.

- ^ Perry, Jonathan (April 8, 2011). "Tune in, turn on..." The Boston Globe. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- ^ Burton, Paul. "Turner, Ted." Notable Sports Figures, edited by Dana R. Barnes, vol. 4, Gale, 2004, pp. 1651–1653.

- ^ "Centennial Olympic Stadium". olympics.com. January 3, 2024. Retrieved September 11, 2024.

Renamed Turner Field – after Ted Turner, the founder of Cable News Network (CNN) whose global headquarters are in the city – the stadium has hosted Major League Baseball (MLB) for almost 20 years.

- ^ a b c d e f Barkin, Steve M. (2016). American Television News: The Media Marketplace and the Public Interest: The Media Marketplace and the Public Interest. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781315290911.

- ^ Wiseman, Lauren (May 10, 2011). "Burt Reinhardt dies at 91: Newsman helped launch CNN". Washington Post. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ "CNN's doomsday video leaks to the Internet". News. January 5, 2015. Archived from the original on February 15, 2020. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- ^ "Faberge Sells Brut's Assets". The New York Times. January 1982. Retrieved November 27, 2014.

- ^ a b Fabrikant, Geraldine (August 8, 1985). "Turner Acquiring MGM Movie Empire". The New York Times. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- ^ You Must Remember This: The Warner Bros. Story, (2008) p. 255.

- ^ "Turner, United Artists Close Deal". Orlando Sentinel. United Press International. August 27, 1986. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- ^ Voland, John (October 23, 1986). "Turner Defends Move to Colorize Films". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (October 30, 1988). "'Casablanca' gets colorized, but don't play it again, Ted". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- ^ Liebenson, Donald (December 11, 2019). "Spike Lee Gets His Fourth Film on the National Film Registry: 'Sometimes Dreams Come True'". Vanity Fair. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- ^ Burgett, Joe (March 11, 2011). "WCW: How It Died, and How WWE and Vince McMahon Made Sure It Never Rose Again". Bleacher Report. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- ^ Tutton, Mark; Brown, Holly; Bresnahan, Samantha (November 29, 2019). "Is Ted Turner the real Captain Planet?". CNN. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- ^ Reuters (December 30, 1992). "Turner Channel for Moscow". The New York Times. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Pelline, Jeff (September 23, 1995). "Time Warner Closes Deal for Turner". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ Flint, Joe; Beatty, Sally (March 7, 2001). "WB Network Chief Kellner Takes Over Turner Operations at AOL Time Warner". Wall Street Journalism. Retrieved June 22, 2024.

- ^ Schneider, Michael (June 22, 2024). "Jamie Kellner, TV Maverick Who Launched Both Fox and The WB, Dies at 77". Variety. Retrieved June 22, 2024.

- ^ Lambert, Jeremy (June 22, 2024). "Former Head of Turner Broadcasting Jamie Kellner Passes Away". Fightful. Retrieved June 22, 2024.

- ^ Hofmeister, Sallie (January 30, 2003). "Ted Turner to Resign AOL Post". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- ^ Associated Press (February 25, 2006). "Ted Turner Leaving Time Warner's Board". The New York Times. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- ^ Ross, Patrick; Hansen, Evan (January 11, 2001). "AOL, Time Warner complete merger with FCC blessing". CNET. Retrieved June 2, 2012.

- ^ Auletta, Ken (April 23, 2001). "The Lost Tycoon". The New Yorker. Retrieved June 24, 2018.

- ^ a b Munk, Nina (July 2002). "Power Failure". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on July 14, 2011. Retrieved June 26, 2018.

- ^ Rutenberg, Jim; Stanley, Alessandra (December 16, 2001). "At 63, Ted Turner May Yet Roar Again". The New York Times. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- ^ Bercovici, Jeff (November 11, 2008). "Ted Turner Goes to Town on Time Warner". Conde Nast Portfolio. Archived from the original on November 13, 2008. Retrieved June 23, 2018.

- ^ Levingston, Steven (February 25, 2006). "Turner To Leave Time Warner". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 24, 2010.

- ^ Frizell, Sam (August 5, 2014). "21st Century Fox Withdraws Time Warner Takeover Bid". Time. Retrieved February 25, 2024.

- ^ Daily Intelligencer (December 23, 2009). "Rupert Murdoch and the Art of War". New York. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- ^ Landler, Mark (October 5, 1996). "Cable News Feud Has Personal and Political Roots". The New York Times. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- ^ "Turner: Murdoch is a 'warmonger'". The Guardian. London. April 23, 2003. Retrieved March 12, 2011.

- ^ Estes, Adam Clark (September 20, 2011). "Ted Turner Still Happy to Spar with Rupert Murdoch". The Atlantic. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- ^ Littleton, Cynthia (April 9, 2019). "Ted Turner: The Maverick Mogul Reflects on His Legacy, Big Deals and Old Feuds". Variety. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- ^ Chass, Murray (January 3, 1977). "Kuhn Suspends Turner, Braves' Owner, for Year in Matthews Case". The New York Times.

- ^ "Horner vs. Turner". 80sbaseball.com. Retrieved September 1, 2021.

- ^ "Ted Turner Managerial Record". Baseball Reference. Retrieved May 17, 2019.

- ^ Hannon, Kent (May 23, 1977). "Benched from the Bench". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on June 15, 2013.

- ^ "Braves sale is approved". Major League Baseball. Archived from the original on August 18, 2017. Retrieved June 12, 2017.

- ^ "Atlanta Hawks retired numbers". Stadiumjourney.com. Archived from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 21, 2021.

- ^ "Golden Plate Awardees of the American Academy of Achievement". Achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement.

- ^ "Paul White Award". Radio Television Digital News Association. Archived from the original on February 25, 2013. Retrieved May 27, 2014.

- ^ Arizona State University. "Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication". Archived from the original on March 20, 2019. Retrieved November 23, 2016.

- ^ "The Edward R. Murrow Lifetime Achievement Award | Murrow Symposium Site | Washington State University". Archived from the original on May 3, 2019. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- ^ "Previous Audubon Medal Awardees". Audubon. January 9, 2015.

- ^ "The Georgia Trustees: Previous Inductees". Georgia Historical Society. March 24, 2014.

- ^ "Lone Sailor Award Recipients". navymemorial.org. Archived from the original on October 16, 2015. Retrieved July 2, 2014.

- ^ Boone, Christian (December 8, 2010). "Ted Turner: Adopt China's one-child policy to save planet". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved March 11, 2019.

- ^ "Working Lunch 1: In Conversation with Ted Turner Archived February 2, 2016, at the Wayback Machine." Global Creative Leadership Summit, September 2009.

- ^ "Stupid Quotes." In The Limbaugh Letter. July 2010. p. 11.

- ^ "Ted Turner endorses Hillary Clinton for President". Fox Carolina. October 10, 2016. Archived from the original on December 9, 2017. Retrieved January 18, 2019.

- ^ Associated Press (September 28, 2018). "CNN founder Turner says network is too heavy on politics". AP News. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- ^ "Turner Foundation". Turner Enterprises Inc. Retrieved September 1, 2021.

- ^ "Ted Turner talks of overpopulation". Bozeman Daily Chronicle. September 18, 1996. Retrieved September 1, 2021.

- ^ Harris, Paul (May 31, 2009). "They're called the Good Club – and they want to save the world". The Guardian. Retrieved September 1, 2021.

- ^ a b Jim Rutenberg (March 19, 2001). "MediaTalk; AOL Sees a Different Side of Time Warner". The New York Times.

- ^ "BBC News – Europe – Heard the one about Ted Turner ..." bbc.co.uk. Retrieved April 12, 2016.

- ^ Burkeman, Oliver; Beaumont, Peter (June 18, 2002). "CNN chief accuses Israel of terror". The Guardian. Retrieved August 31, 2016.

- ^ Boone, Christian (December 8, 2010). "Ted Turner: Adopt China's one-child policy to save planet". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved September 26, 2014.

- ^ a b "About – Turner Enterprises". Tedturner.com. Retrieved January 28, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e "Turner Ranches FAQ – Turner Enterprises". Tedturner.com. Retrieved January 28, 2020.

- ^ Tribune staff (2009). "125 Montana Newsmakers: Ted Turner". Great Falls Tribune. Archived from the original on July 11, 2011. Retrieved August 28, 2011.

- ^ a b "Ranches". Ted Turner. Archived from the original on April 30, 2009. Retrieved March 29, 2009.

- ^ Morgan, Rhett (February 3, 2016). "Osage Nation set to buy Ted Turner-owned Bluestem Ranch in Osage County". Tulsa World. Retrieved April 7, 2017.

- ^ "State, Vermejo Park Ranch Enter Into Agreement Regarding Abandoned Mine Reclamation". allbusiness. April 14, 2006. [dead link]

- ^ "Turner Foundation". Turnerfoundation.org. Archived from the original on August 17, 2020. Retrieved October 21, 2021.

- ^ "Captain Planet Foundation – Engaging & empowering young people to be problem solvers for the planet". Captainplanetfoundation.org. Retrieved October 21, 2021.

- ^ "Ted Turner Reserves – Luxury Eco-Tourism". Tedturnerreserves.com. Retrieved October 21, 2021.

- ^ "Turner Renewable Energy – Turner Enterprises". Tedturner.com. Retrieved October 21, 2021.

- ^ "Turner Building – Turner Enterprises". Tedturner.com. Retrieved January 28, 2020.

- ^ "Turner Renewable Energy – Turner Enterprises". Tedturner.com. Retrieved January 28, 2020.

- ^ "Executive Leadership – Turner Enterprises". Tedturner.com. Retrieved January 28, 2020.

- ^ "A Conversation With Ted Turner". April 1, 2008. Archived from the original on April 5, 2008. Retrieved April 6, 2008.

- ^ "CNN.com Video". CNN. May 4, 2012. Retrieved October 31, 2008.

- ^ Smith, Bruce. Ted Turner's son vying in SC congressional primary Archived December 3, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, Associated Press, January 23, 2013.

- ^ "SC District 01 – Special R Primary". SC Elections. Retrieved October 26, 2017.

- ^ "Ted Turner's Giving Pledge" (PDF). The Giving Pledge. June 30, 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 23, 2012.

- ^ "The Sure Thing: How entrepreneurs really succeed". The New Yorker. Retrieved May 10, 2016.

- ^ Kloer, Phil (November 10, 2008). ""Call Me Ted" – what else do you call him?". Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on January 1, 2010. Retrieved November 12, 2008.

- ^ "Ted Turner reveals he's battling Lewy body dementia in exclusive interview". CBS News. September 28, 2018. Retrieved September 29, 2018.

- ^ Haupert, Michael John (2006). The Entertainment Industry. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 253. ISBN 978-1-59884-594-5. Retrieved June 3, 2014.

- ^ "Courageous". 2017 America's Cup. June 17, 2017. NBC.

- ^ Wallace, William (June 19, 1977). "U.S. Yachts Begin America's Cup Trials". The New York Times. Retrieved October 1, 2017.

- ^ a b "Noel Robins". ACCyclopedia. Archived from the original on July 7, 2012. Retrieved January 30, 2012.

- ^ "Courageous – US 26". americascup.com. Archived from the original on February 22, 2010. Retrieved April 27, 2011.

- ^ "Ted Turner, Captain Outrageous". Sailing World. April 24, 2002.

- ^ Rousmainiere, John (1980). Fastnet, Force 10. New York: Norton. ISBN 0-393-03256-6.

- ^ "Ted Turner on Sports Illustrated cover". CNN. July 4, 1977. Archived from the original on May 15, 2011. Retrieved April 27, 2011.

- ^ "A Brash Captain Keeps the Cup". The New York Times. September 18, 1977.

- ^ "Herreshoff Marine Museum & America's Cup Hall of Fame". Herreshoff.org. Archived from the original on April 16, 2012. Retrieved October 10, 2012.

- ^ "Turner, Ted – 2011 Inductee". Nshof.org. Archived from the original on December 10, 2013. Retrieved October 10, 2012.

- ^ a b c Wu, Tim (November 10, 2010). "Ted Turner, the Alexander the Great of Television". Slate. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ a b "Viewpoint: Let's never forget the legacy of Ted Turner". March 6, 2019. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ "Eric Bischoff Recalls Vince McMahon's Letters 'Trying to Embarrass' Ted Turner". September 12, 2020. Retrieved February 25, 2021.

- ^ "MATS ENTERTAINMENT! WRESTLING FOES MCMAHON, HOGAN SQUARE OFF IN TALK-SHOW TUSSLE". June 28, 1999. Retrieved August 26, 2021.

- ^ Thakur, Sanjay (July 30, 2021). "Vince McMahon Says He Does Not See AEW As The Same Level Of Competition As WCW". Pro Wrestling News Hub. Retrieved November 28, 2024.

Further reading

- Call Me Ted by Ted Turner and Bill Burke (Grand Central Publishing, 2008) ISBN 978-0-446-58189-9

- Racing Edge by Ted Turner (Simon & Schuster, 1979) ISBN 0-671-24419-1

Biographies

| External videos | |

|---|---|

- Media Man: Ted Turner's Improbable Empire by Ken Auletta (W. W. Norton, 2004) ISBN 0-393-05168-4

- Clash of the Titans: How the Unbridled Ambition of Ted Turner and Rupert Murdoch Has Created Global Empires that Control What We Read and Watch Each Day by Richard Hack (New Millennium Press, 2003) ISBN 1-893224-60-0

- Me and Ted Against the World: The Unauthorized Story of the Founding of CNN by Reese Schonfeld (HarperBusiness, 2001) 0060197463

- Ted Turner Speaks: Insights from the World's Greatest Maverick by Janet Lowe (Wiley, 1999) ISBN 0-471-34563-6

- Riding A White Horse: Ted Turner's Goodwill Games and Other Crusades by Althea Carlson (Episcopal Press, 1998) ISBN 0-9663743-0-4

- Porter Bibb (1996). Ted Turner: It Ain't As Easy as It Looks: The Amazing Story of CNN. Virgin Books. ISBN 0-86369-892-1.

- Citizen Turner: The Wild Rise of an American Tycoon by Robert Goldberg and Gerald Jay Goldberg (Harcourt, 1995) ISBN 0-15-118008-3

- CNN: The Inside Story: How a Band of Mavericks Changed the Face of Television News by Hank Whittemore (Little Brown & Co, 1990) ISBN 0-316-93761-4

- Lead Follow or Get Out of the Way: The Story of Ted Turner by Christian Williams (Times Books, 1981) ISBN 0-8129-1004-4

- Atlanta Rising: The Invention of an International City 1946–1996 by Frederick Allen (Longstreet Press, 1996) ISBN 1-56352-296-9

External links

- Official website

- Robert Edward “Ted” Turner Biography and Interview on American Academy of Achievement

- Ted Turner collected news and commentary at The New York Times

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Ted Turner at IMDb

- Ted Turner at The Interviews: An Oral History of Television

- Turner on Oprah Master Class, aired January 29, 2012 Archived September 1, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- Ted Turner managerial career statistics at Baseball-Reference.com

- Robert Turner III at World Sailing

- 1938 births

- 1974 America's Cup sailors

- 1977 America's Cup sailors

- 21st-century American philanthropists

- 5.5 Metre class sailors

- Activists from Ohio

- American advertising executives

- American cable television company founders

- American chief executives in the media industry

- American conservationists

- American landowners

- American male sailors (sport)

- American businesspeople in real estate

- American television company founders

- Atlanta Braves executives

- Atlanta Braves managers

- Atlanta Braves owners

- Atlanta Hawks executives

- Atlanta Hawks owners

- Atlanta Thrashers executives

- Atlanta Thrashers owners

- Brown Bears sailors

- Businesspeople from Cincinnati

- Businesspeople from Georgia (U.S. state)

- CNN executives

- Georgia (U.S. state) Democrats

- International Emmy Directorate Award

- Living people

- Major League Baseball team presidents

- Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer executives

- Peabody Award winners

- Professional wrestling promoters

- Time Person of the Year

- United Nations Foundation

- United States Coast Guard enlisted

- United States Coast Guard reservists

- US Sailor of the Year

- 5.5 Metre class world champions

- World champions in sailing for the United States

- World Championship Wrestling executives

- People with Lewy body dementia

- Benjamin Franklin Medal (Franklin Institute) laureates