Tribes of Yemen

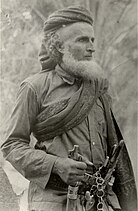

Yemeni Tribesmen | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 200–400 tribes | |

| Languages | |

| Arabic (Yemeni), minority Mehri, Hobyot, and Socotri | |

| Religion | |

| Islam (Shafi'i, Zaydi) |

The Tribes of Yemen are those residing within the borders of the Republic of Yemen. While there are no official statistics, some studies suggest that tribes make up about 85% of the population, which was 25,408,288 as of February 2013.[1][2] Estimates vary, with approximately 200 tribes in Yemen, although some reports list more than 400.[3][4] Yemen is notable as the most tribal nation in the Arab world, largely due to the significant influence of tribal leaders and their deep integration into various aspects of the state.[5]

Many tribes in Yemen have long histories, with some tracing their roots back to the era of the Kingdom of Sheba. Throughout history, these tribes have often formed alliances, either to establish or dismantle states. Despite their diverse origins, they frequently share common ancestry. In Yemen, the lineage of the tribe is less important than the alliances it forms.[6] Tribes are far from homogeneous societal structures. While several clans may share a common history and "lineage," the tribe in Yemen is not a cohesive political entity. Clans belonging to a common "lineage" may shift their affiliations and loyalties as dictated by needs and circumstances,[7] with the allied tribe also finding a shared "lineage."[8]

Over long periods of time, Yemen remained a unified nation despite the lack of a central government that imposed authority over the entire territory, except for brief periods in Yemen's history. The nation was made up of numerous tribes, and the tribal divisions in Yemen stabilized with the advent of Islam into four federations: Himyar, Madhhaj, Kinda, and Hamdan.[9] The Madhhaj tribe group consists of three tribes—Ans, Murad, and Al-Hadda—and they inhabit the eastern regions of Yemen. The Himyar tribes lived in the southern mountainous regions and central plateaus, while the Hamdan federation includes the Hashid and Bakil tribes.[10] The political and economic conditions in Yemen during the Middle Ages and the early modern era led to the redrawing of the tribal map. The Madhhaj tribes joined the Bakil tribal confederation, and some Himyar tribes joined the Hashid confederation.[11]

Origins

[edit]Classes of Arabs

[edit]Most genealogists and historians classify the Arab peoples into two categories: defunct Arabs and those remaining.[12] Defunct Arabs refer to ancient Arab tribes that once lived on the Arabian Peninsula but disappeared before the advent of Islam. No descendants of these tribes remain today due to changes in the natural environment and volcanic eruptions.[13] These tribes include ‘Ād, Thamud, Amliq, Tasm, Jadis, Umim, and Jassim, with Abeel, the first urn, and Dabbar occasionally included.

The remaining Arabs are the descendants of Yarub bin Qahtan and the sons of Ma`ad bin Adnan bin Ad, who adopted the Arabic language from the defunct Arabs. Qahtan and his group became Arabized when they settled in Yemen and mixed with the local people. According to one narration, Qahtan originally spoke Syriac, but his language gradually changed to Arabic as he became Arabized.[14][15]

There is another classification that divides the Arabs into three categories: defunct Arabs, Arabized Arabs, and Mozarabized Arabs. The latter two categories are collectively known as "remaining Arabs." The Arabs are those descended from Qahtan (or Joktan), as mentioned in the Old Testament.[16] He was the first to speak Arabic, and his descendants are considered the authentic and ancient Arabs. These include the Al-Qahtaniyah from the Himyar, the people of Yemen and its branches, representing the people of southern Arabia, as opposed to the Musta'arabi Jews of the Levant. Additionally, there are the Maadis, who descend from Ma`ad ibn Adnan ibn Ad. They inhabited Najd, Hijaz, and the northern regions and are descended from Ismail ibn Ibrahim. This group became Arabized following the Muslim conquest of the Iberian Peninsula, and they were known as Mozarabs. When Ismail came to Mecca, he spoke Hebrew or Aramaic, but upon assimilating with the Yemenites, he learned their Arabic language.[17]

Ibn Khaldun divides the Arabs into four successive classes over a chronological range: first, the defunct Arabs; second, the Qahtaniyah Arabs; third, the Arabs belonging to them, including those from Adnan, Aws, Khazraj, Ghasasna, and Manathira; and fourth, the Arabs of Al-Mustajimah, who were influenced by the Islamic State.[17][18]

In fact, the division between the Arabs and the Arabized Arabs originates from what is written in the Old Testament and is derived from accounts of the beginning of creation. Subsequently, genealogists and historians agreed to divide the Arabs, in terms of lineage, into two groups: the Qahtaniyah, whose original homeland was Yemen, and the Adnaniyah, whose original homeland was Hijaz.[19][20]

History

[edit]Ancient tribal history

[edit]In ancient times, the tribal structure was organized around tribal unions, including the Kingdom of Sheba, Qataban, Ma'in, and Hadhramaut. These four kingdoms gave rise to various tribes. After the advent of Islam, historians knew little about Qataban and Ma'in. As a result, tribes previously affiliated with these kingdoms were often classified under Saba or Himyar, as they were mentioned in the Qur'an or associated with Himyar, the last of the ancient Yemeni kingdoms before Islam.[21][22] The strongest of these unions was the Sabaean, which established a system similar to federalism, encompassing the four kingdoms and their tribes.

Kingship in Sheba was held by specific tribes or "covens," as indicated by the Sabaean terms "Fishan," "Dhu Khalil," "Dhu Sahar," and "Dhu Ma'ahir." Currently, little is known about these groups, and they are not mentioned in existing writings.[23] Their rule marked the kingdom's most prosperous period, believed to have lasted from the 12th century BCE to the 4th century BCE.[24]

These kings established a "federal" system of governance, granting each tribe or province a degree of autonomy while maintaining military and economic subordination to the kingdom, primarily through tax payments.[25] The unique geography of Yemen played a significant role in the emergence of tribes. The mountains and narrow valleys isolated communities from one another, leading to the formation of tribal groups that allied with each other for mutual protection while remaining wary of nearby groups.

Urban Arabs built forts and castles to defend themselves and their resources against both neighboring tribes and external threats. Similarly, the Ahlaf, or tribal alliances, served as protection for Bedouins in the desert. The scarcity of resources in the Arabian Peninsula historically drove people to form isolated tribal groups scattered across the region. Even urban dwellers maintained strong tribal ties and sometimes fabricated lineages to reinforce their alliances, reflecting a deep-seated fear of an uncertain future.[citation needed]

The civilization of the Kingdom of Sheba began to decline after the collapse of the Ma’rib Dam.[26] This catastrophic event caused widespread flooding of the surrounding villages, cities, and farms, forcing the population to migrate both internally and externally to nearby and distant regions.[27] After the event known as Sil al-Aram, the people of Ma'rib dispersed across the land. However, the tribes of Himyar, Madhhaj, and Kinda remained in Yemen, along with Ash'ari and Anmar (Khath'am and Bajila).[28]

Yemen then entered a new era characterized by religious conflicts during the period of the Himyarite State. It became a battleground for competing external powers, particularly the Sassanians and the Roman Empire. This rivalry between foreign powers, driven by greed, brought about significant instability in Yemen.[29]

The Romans sought to introduce Christianity to Yemen to establish political and economic influence in the region. Their trade routes passed through Yemen, connecting the Arabian Gulf and the Red Sea. Meanwhile, the Jewish presence in Yemen grew as Jews fleeing Roman persecution, especially after the destruction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem in 70 CE, sought asylum there.

As the influence of the Jewish community in Yemen increased, tensions arose with Roman Christians. Fueled by a spirit of revenge, the Jewish king Dhu Nuwas al-Himyari of the Al-Diyaniyya dynasty persecuted Christians who refused to convert to Judaism. He famously dug trenches for them and set them on fire, a brutal act that marked a dark period in Yemen's history.[30]

The Abyssinians invaded Yemen in 533 CE with the goal of eliminating their Persian rivals and reclaiming control of the trade routes. Their leader, Aryat, assumed power after overthrowing the Himyarite King Dhu Nuwas. In 535 CE, Abraha al-Habashi declared himself king of Yemen after breaking away from the Axumite state in Abyssinia.

Abraha ruled independently and sought to spread Christianity throughout the Arabian Peninsula. He aimed to redirect Arab pilgrimage from Mecca to a grand cathedral he built in Sanaa, known as Al-Qalis. In 570 CE, he famously attempted to invade Mecca, an event remembered as the "Year of the Elephant." Abraha was later succeeded by his son, Axum.[citation needed]

Saif bin Dhi Yazan Al-Himyari, a prominent noble of Himyar, sought assistance from the Persians to expel the Abyssinians from Yemen. With Persian support, Saif bin Dhi Yazan successfully ended the 72-year Abyssinian rule over Yemen. However, this victory brought Yemen under Persian control, marking the beginning of a new colonial era.[31]

During this period, Yemen experienced political, tribal, religious, and intellectual fragmentation. Sana'a and its surrounding regions were directly subjected to Persian rule, with the Persians forming a distinct class known as the "Sons." Meanwhile, Yemeni regions beyond Persian control remained mired in conflicts and tribal disputes, a state of unrest that persisted until the emergence of Islam.[32]

Muhammad's era

[edit]

Several researchers believe that the rapid conversion of the Himyarites, Hamdan, and Hadhramaut tribes to Islam can be attributed to their longstanding adherence to a monotheistic religion prior to Islam. However, neither Mu'adh ibn Jabal, Ali ibn Abi Talib, nor Abu Musa Al-Ash’ari stayed long in these regions before the tribes embraced Islam.[33]

The Bedouin tribes, such as Kinda and Madhhaj, took a different stance during this period. A battle erupted between the Hamdan tribe and the Murad branch of Madhhaj, during which Madhhaj suffered defeat at the hands of Hamdan. Despite their historical ties, Kinda and Madhhaj faced internal tensions. Farwa bin Al-Musayk Al-Muradi, a leader of the Madhhaj tribe, reportedly severed ties with the kings of the Kingdom of Kinda after they betrayed him during the battle.

Following this, Farwa went to meet Muhammad, converted to Islam, and was appointed by Muhammad to oversee the collection of alms. Meanwhile, the tribes of Khawlan, Nahd, and Nakha` from Madhhaj, along with the Ash'ari people under Abu Musa Al-Ash'ari, eagerly anticipated their meeting with Muhammad, saying, “Tomorrow we will meet our beloved Muhammad and his companions.” Muhammad, in response, warmly welcomed them and praised their arrival.[34]

"The people of Yemen have come to you. They are weaker in heart and softer in understanding, faith is Yemeni and wisdom is Yemeni."

The remaining members of Madhhaj maintained their allegiance to Kinda and resented the appointment of Farwa bin Al-Musayk Al-Muradi as head of charity. Consequently, Amr ibn Maadikarb Al-Zubaidi and several members of Madhhaj defected and joined al-Aswad Al-Ansi. However, Farwa successfully defeated Amr ibn Maadikarb, and his son Qays later joined Fayrouz Al-Dailami, the slayer of al-Aswad Al-Ansi.[35]

During this time, Muhammad dispatched Mu'adh ibn Jabal to Yemen and established the Al-Jund Mosque in Taiz, located on the lands of Al-Sukun and Al-Sakasik, which were part of the Kingdom of Kinda. This mosque is the second-oldest in Yemen.[36] After Muhammad's death, tribal divisions reemerged. Narratives mention that Al-Ash’ath ibn Qays, the leader of Banu Al-Harith ibn Jabla from Kinda, refused to pay zakat.[37] Sharhabeel ibn Al-Samat Al-Kindi, hostile to Al-Ash'ath, ultimately killed him. Kinda, divided during this period, continued to experience internal hostilities into the Umayyad era.[38]

Sharhabeel became the governor of Homs under Muawiyah and was instrumental in dividing tribal settlements there.[39] He opposed Ali ibn Abi Talib and played a significant role in the Battle of Siffin. Conversely, Al-Ash'ath fought in Ali's army.[40] Some members of Kinda were reportedly Christians, including the Christian prince of Najran who visited Muhammad.[41]

Abu Bakr Al-Siddiq sent a force to besiege Al-Ash'ath, who had fortified himself in a stronghold called Al-Najir. Meanwhile, the tribes of Banu Tajib and Al-Sakasik Al-Kindi, led by Al-Husayn bin Al-Numair Al-Sakuni, fought against Al-Ash'ath. After four months, Al-Ash'ath surrendered, converted to Islam again, and joined Muslim forces in campaigns in the Levant and Iraq. He participated in the Battle of Al-Qadisiyah, leading 3,000 fighters under Saad bin Abi Waqqas and was among those sent to negotiate with Yazdgerd III.[42]

Later, Al-Ash'ath suppressed a second rebellion in Azerbaijan and became its governor during the caliphate of Uthman ibn Affan, though some sources attribute his governance to Ali ibn Abi Talib's era.[43] He died in Kufa during the caliphate of Hasan bin Ali.[44]

Al-Ash'ath married Farwa bint Abi Quhafa after being freed by Abu Bakr Al-Siddiq, which upset Uyaynah ibn Muhsin, as his similar plight did not result in such an alliance. In response, Salem bin Dara Al-Ghatfani, a poet from Uyaynah’s tribe, composed verses expressing his frustration.

Uyaynah bin Hisn Al Adi, you are one of your people, to the core and core I am not like the shaggy, crowned boy who has mastered and is weaned His grandfather the bitter eater and Qais/his speeches about the kings were great speeches If you two have come to an engagement/excuse other than you, it will be eternal He has the prestige of kings and of Al-Ash'ath if an old incident comes Al-Ash`ath ibn Qays ibn Maadi has anguish and pride, and you are an animal.

Hadhramaut embraced Islam following the conversion of its prominent leader, Wael bin Hajar, after receiving a letter from the Prophet Muhammad. Wael traveled to Medina, where Muhammad ordered the call to prayer in his honor upon his arrival. While the exact duration of Wael's stay in Medina is unknown, it is reported that Muhammad instructed Muawiyah bin Abi Sufyan to accompany him when he departed.

Wael and his people remained steadfast in Islam. He later passed away in Kufa during the reign of Muawiyah. Wael led the banner of Hadhramaut during the Battle of Siffin as part of Ali ibn Abi Talib's army.[45] Additionally, the people of Hadhramaut participated in the Muslim conquests of Egypt. It is said that Muawiyah bin Abi Sufyan recommended them for roles as judges and record-keepers in Egypt, favoring them over other tribes alongside the Azd.[46]

The Rashidun Caliphate

[edit]Yemen enjoyed stability during the period of the Rightly Guided Caliphate. The Rashidun Caliphate divided Yemen into four provinces: Sana'a (along with Najran),[47] Mikhlaf al-Jand (central Yemen), Mikhlaf Tihama, and Mikhlaf Hadhramaut. Their rule was stable, and not much is known about this period until the late ninth century AD. However, historical sources, particularly those from Yemen, provide details of Yemeni involvement in Islamic conquests.

Abu Bakr al-Siddiq sent Anas bin Malik to Yemen to encourage participation in the Levantine campaigns.[48] Anas bin Malik sent a letter to Abu Bakr, reporting the response from the people of Yemen. Dhu al-Kala` al-Himyari arrived with a few thousand of his people to join the effort.[49] Additionally, Al-Ala bin Al-Hadrami conquered Bahrain, fighting those who had apostatized from Islam, and both Abu Bakr and Omar appointed him to govern Bahrain, as the Prophet had previously done.[50]

Al-Samat bin Al-Asut Al-Kindi, Muawiyah bin Khadij al-Tujaybi, Dhu al-Kala` al-Himyari, and Hawshab Dhu Dhalim al-Himyari each led forces in the Battle of Yarmouk, commanding units known as Kardus. Sharhabeel bin Al-Samat Al-Kindi, who is said to have governed Homs with Al-Miqdad bin Al-Aswad, ruled for twenty years and was responsible for dividing the land among the people.[51] Later, Malik bin Hubayra al-Kindi took charge, serving as the commander of Muawiyah's armies against the Romans.[52]

The Kingdom of Kinda played a vital role in the military forces of the Jund of Homs and the Jund of Palestine.[53][54] Bin Khadij al-Tujaybi was involved in the campaigns at Jalawla and confronted the Roman forces.[55]

When Saad bin Abi Waqqas left Medina heading to Iraq at the head of four thousand fighters, three thousand of whom were from Yemen,[56] the number of fighters from Mazhaj in the Battle of Al-Qadisiyah was two thousand and three hundred out of ten thousand.[57][58] Their leader was Malik bin Al-Harith Al-Ashtar Al-Nakha'i, and Al-Nakha' is from Abyan, where they still reside. Hadhramaut contributed seven hundred fighters.[59] Amr bin Maadikarb Al-Zubaidi fought on the right flank of Saad bin Abi Waqqas in that battle.[57][58]

Omar Ibn Al-Khattab swore allegiance to Mazhaj, which was divided between Iraq and the Levant. They preferred to move toward the Levant and disliked the idea of going to Iraq, unlike other people from Yemen. There were four chiefs over Mazhaj: Amr bin Maadikarb Al-Zubaidi, Abu Sabra bin Dhu’ayb Al-Jaafi, Yazid bin Al-Harith Al-Sada'i, and Malik Al-Ashtar Al-Nakha'i.[60] Al-Ash'ath Ibn Qays led one thousand seven hundred fighters and participated with Sharhabeel Ibn Al-Samat in the battle as well.[61]

Duraid bin Ka'b Al-Nakha'i carried the banner of Al-Nakha' during the "Night of the Harrier," when the Kinda Kingdom was defeated by the Persians. Similarly,[62] Qais bin Makshuh Al-Muradi commanded the force that attacked Rustam.[63] Mazhaj was one of the most prominent groups in that battle, with one boy from their tribe leading sixty or eighty prisoners of the Persian Empire.[64] Even the women of Mazhaj participated in the battle, with seven hundred women taking part.[65] Additionally, people from Bani Nahd participated in the conquest of Tabaristan.[66]

In the twentieth year of the Hijra, Abdullah bin Qais al-Taraghmi al-Kindi invaded the Romans at "the sea" at the urging of Muawiyah bin Abi Sufyan, despite Omar's hesitation on the matter.[67] Muawiyah bin Khadij al-Tujaybi al-Kindi was part of a delegation to Omar ibn al-Khattab during the conquest of Alexandria, and the Yemenis formed the majority of the army of Amr ibn al-Aas. They were responsible for planning Fustat and distributing housing on a tribal basis.[68]

The planning of Fustat was supervised by four people: Muawiyah bin Khadij al-Tujaybi, Shareek bin Sami al-Ghataifi from Murad Mazhaj, Amr bin Qazam Al-Khawlani, and Haywal bin Nashirah Al-Maafiri. Most of the tribes residing in Fustat were Yemeni,[69] including Al-Maafir, Khawlan, Ak, Ash'ari, and Tajib. Hamdan also participated in the conquests of Egypt, North Africa, and Andalusia, with Hamdan and the Kingdom involved in Giza.[70]

Abdullah bin Aamer al-Hadrami assumed the governorship of Mecca during the time of Othman bin Affan.[71] Al-Ash'ath bin Qays was appointed governor of Azerbaijan. Yemen was divided between Ali ibn Abi Talib and Muawiyah bin Abi Sufyan, with the majority of Hamdan siding with Ali. Their leader, Saeed bin Qais Al-Hamdani, carried the Hamdan banner in both the Battle of the Camel and the Battle of Siffin.[72] Yazid bin Qais Al-Arhabi Al-Hamdani served as one of the messengers of Ali ibn Abi Talib to Muawiyah bin Abi Sufyan, urging him to obey Ali.[73]

A large portion of Hamdan remains Shiite to this day, with factions including Zaidi and Ismaili followers. The rest of the tribes were divided between the two factions.[74][75] Malik al-Ashtar al-Nakha’i led three thousand horsemen in the army of Ali ibn Abi Talib during the Battle of Siffin, accompanied by Shurayh bin Hani al-Harithi, Ziyad bin al-Nadr al-Harithi, and Ammar bin Yasser al-Ansi, all of whom were from Mazhaj.[76] The heart of Ali's army in the Battle of Siffin was composed of Yemenis,[77] and many loyalists from Hamdan were killed in that battle. Whenever one of them fell, the banner would be passed to another.[78] Malik al-Ashtar would rally his people from Mazhaj, saying:[78]

"You are the sons of wars, the raiders, the youth of the morning, the dead of the peers, and Madhhaj al-Ta'an"

While Sharhabeel bin Al-Samat Al-Kindi and Malik bin Hubayra Al-Kindi were in the army of the Levant, Hajr bin Adi Al-Kindi and Al-Ash'ath bin Qays were also part of the army of the Levant. Abd al-Rahman bin Mahrez al-Kindi and others fought alongside Ali.[79] Dhu al-Kila' al-Himyari supported Muawiyah, and with him were four thousand of his people. He attacked those loyal to Ali, wounding some of them. They were known for their great character.[80]

Muawiyah bin Khadij al-Tajibi al-Kindi pursued Muhammad bin Abi Bakr al-Siddiq in Egypt and killed him by inserting him into the belly of a donkey and burning him.[81] Muawiyah bin Abi Sufyan directed Abdullah bin Amer al-Hadrami to Iraq to rally support for his side.[82] One of the people from Mazhaj, Abdul-Rahman bin Muljam al-Muradi, a Khariji, was the one who killed Ali ibn Abi Talib.[83]

After the killing of Ali, Muawiyah bin Abi Sufyan ordered the execution of Hajar bin Adi al-Kindi. However, Malik bin Hubayra al-Kindi, one of the commanders of the Levant army in the Battle of Siffin, interceded on the grounds that Hajar was the leader of those who opposed and criticized Muawiyah.[84] Muawiyah accepted his intercession through Abdullah bin Al-Arqam Al-Kindi.[85]

The killing of Hajar bin Adi stirred strong reactions, including from the Yemeni tribes, even Muawiyah bin Khadij Al-Tujaybi.[86] In response, Muawiyah sent one hundred thousand dirhams to Malik bin Hubayra al-Kindi to silence him.[87] Things eventually returned to normal, and the conquests resumed.

Rabi’ bin Ziyad al-Harithi al-Madhaji went to Khorasan and conquered it, while Yazid bin Shajara al-Rahawi al-Madhaji and Abdullah bin Qais al-Taragmi al-Kindi invaded the sea and Sicily, with Abdullah being the first Arab to do so.[88][89] Bin Hudayj al-Tujaybi invaded Africa (Tunisia) three times, including an invasion of Nubia, where he lost an eye and became one-eyed.[90] He later assumed the emirate of Egypt and Crenasia.[91]

Muawiyah died, and Hamdan remained loyal to the sons of Ali ibn Abi Talib, with Abu Thumama al-Sayidi al-Hashidi as their leader. This loyalty extended to parts of the Kinda Kingdom and Mazhaj. Muhammad bin Al-Ash'ath and Muslim bin Aqeel were killed, while Amr bin Aziz al-Kindi and his son Ubayd Allah were in control of a quarter of the Kinda Kingdom. Rabi'ah pledged allegiance to Al-Hussein bin Ali.[92]

However, Muhammad bin Al-Ash'ath al-Kindi feared for the life of Hani’ bin Urwa al-Muradi al-Madhaji, an ally of Muslim bin Aqeel in Iraq, as he was at risk of being killed.[93] Hani’ was ultimately slain by a servant of Ubaid Allah bin Ziyad, named Rashid. In response, Abdul Rahman bin Al-Husayn al-Muradi proceeded to avenge his master by killing Ibrahim bin Al-Ashtar al-Nakha’i al-Mazhaji, who had been a key figure in opposing Ubayd Allah ibn Ziyad.[94][95]

Umayyads

[edit]Historical sources are very scarce regarding the situation of Yemen during that period. As with previous crises, the Yemenis were divided between Hussein bin Ali and Yazid bin Muawiyah, with the exception of Hamdan, which continued to mourn Hussein until the caliphate of Marwan ibn al-Hakam.[96] Kinda acquired thirteen members of the family of Hussein ibn Ali, while Mazhaj acquired seven.[97] Sinan bin Anas al-Nakha'i al-Mazhaji was the one who cut off the head of Hussein.[98]

As for Hamdan, many of them were killed in the Battle of Karbala, with the most prominent among them being Abu Thumama al-Saidi, Habashi bin Qais al-Nahmi, Hanzalah bin Asaad al-Shabami (a relative of Shibam Kawkaban), Saif bin al-Harith bin Saree al-Jabri, Ziyad bin Urayb al-Saidi, Siwar bin Munim Habis al-Hamdani, Abas bin Abu Shabib al-Shakri, and Barir bin Khudair al-Hamdani.[99]

There were also individuals from Hadhramaut who participated in the battle alongside the Umayyads, including Hani bin Thabit al-Hadrami, Usayd bin Malik al-Hadrami, and Sulaiman bin Awf al-Hadrami.[100] Hakim bin Munqidh al-Kindi rode out to Kufa on horseback, mobilizing people to avenge Hussein in the year 65 AH.[101] He was among those killed, alongside Sulaiman bin Sard al-Khuza'i, during the Revolution of the Tawabin.[citation needed]

Some sources suggest that Yemen pledged allegiance to Abdullah bin Al-Zubayr in addition to the Hijaz,[102] although details regarding this are scarce. However, Al-Husayn bin Al-Numair Al-Sakuni Al-Kindi played a major role in gathering the people of Yemen in the Levant alongside Marwan bin Al-Hakam.[103] Before that, he was part of the army of Muslim bin Uqba, who invaded Medina during the Battle of al-Harra in the caliphate of Yazid bin Muawiyah. Al-Numair then left the army and went to Mecca at Yazid's command, where he besieged Abdullah bin Al-Zubayr.[104]

Al-Numair pledged allegiance to Marwan ibn al-Hakam, and a number of people from the Kinda Kingdom insisted that Al-Husayn bin Al-Numair present Khalid ibn Yazid ibn Muawiyah to them, as they were his maternal uncles.[105] However, they pledged allegiance to Marwan ibn al-Hakam on the condition that they be given Balqa in Jordan, which Marwan agreed to.[106]

Two tribes of Kinda (Al-Sukun and Al-Sakasik) fought alongside Marwan bin Al-Hakam in the Battle of Marj Rahit, which solidified Marwan's rule and marked the beginning of the second phase of the Umayyad state. This battle was also one of the key events that contributed to the development of tribal divisions among the Arabs.[107]

Many from Hamdan, Nakha, Mazhaj, and Bani Nahd joined Al-Mukhtar al-Thaqafi in his revolution to investigate the killers of Hussein. Asim bin Qais bin Habib Al-Hamdani led a faction from Hamdan and Bani Tamim,[108] while Malik bin Amr al-Nahdi and Abdullah bin Sharik al-Nahdi led the Bani Nahd.[109] Sharhabil bin Wars al-Hamdani led three thousand fighters, mostly mawali (non-Arabs), with only seven hundred Arabs among them. They headed towards Medina and then to Mecca to besiege Abdullah bin Al-Zubayr. However, he was killed by a plot orchestrated by bin Al-Zubayr, and the rest of Sharhabil's army returned to Basra.[110]

Al-Husayn bin Numair Al-Sakuni was killed during Al-Mukhtar al-Thaqafi's revolution. Al-Mukhtar was eventually killed during Mus'ab bin Al-Zubayr's campaign against him. To the right of Al-Mukhtar was Salim bin Yazid Al-Kindi, and to his left was Saeed bin Munqidh Al-Hamdani. Muhammad bin Al-Ash’ath Al-Kindi fought alongside Mus'ab bin Al-Zubayr.[111]

When Abd al-Malik bin Marwan entered Kufa, he was surprised to see Bani Nahd, despite their small number. They claimed, "We are stronger and more powerful." When he asked, "By whom?", they replied, "By you, Commander of the Faithful." Kinda also joined Abd al-Malik, with Ishaq bin Muhammad al-Kindi leading them.[112] Abd al-Rahman bin Muhammad al-Kindi, also known as "Ibn al-Ash’ath," later led a famous revolution at the head of five thousand fighters against the Kharijites.[113] Uday bin Uday al-Kindi and Amira bin al-Harith al-Hamdani were sent to fight against Saleh Ibn Masrah al-Tamimi, a Khariji, who was eventually killed.[114]

In the year 80 AH, Abdul-Rahman bin Muhammad bin Al-Ash’ath Al-Kindi headed to Sistan, after the destruction of the army of Ubayd Allah bin Abi Bakra by the Turks. The relationship between Al-Hajjaj bin Yusuf and Abdul-Rahman was very strained, to the point that Abdul-Rahman’s uncle urged Al-Hajjaj not to send him. Abdul-Rahman, who used to call Al-Hajjaj "Ibn Abi Raghal," was known for his arrogance. Whenever Al-Hajjaj saw Abdul-Rahman, he would say, “How arrogant he is! Look at his walk! By God, I was about to behead him.” Abdul-Rahman took pride in his lineage, tracing it back to the kings of the Kingdom of Kindah.[115] He would sit among his Hamdan uncles and say, “As Ibn Abi Raghal says, if I do not try to remove him from his authority, I will exert myself until we both stay.”[116]

Abdul-Rahman set out at the head of forty thousand fighters, and people began to call his army the “peacock army.”[117] He invaded the Turkish lands, and when their leader offered to pay tribute to the Muslims, Abdul-Rahman refused to respond until he had annexed a large part of their country. He stopped only due to the onset of winter. Al-Hajjaj sent a letter to Abdul-Rahman, forbidding him to stop and threatening to depose him and appoint his brother Ishaq bin Muhammad al-Kindi as commander.[118] Abdul-Rahman consulted his soldiers and, supported by Amer bin Wathilah Al-Kinani, called for the removal of Al-Hajjaj, whom he considered "the enemy of God."[119] This marked the beginning of one of the most intense revolts against the Umayyad state.

Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan sent supplies to Al-Hajjaj, who killed Abdul-Rahman bin Al-Ash'ath, Mutahhar bin Al-Harr al-Judhami, and Abdullah bin Rumaitha al-Tai. Al-Hajjaj then stormed Basra, which pledged allegiance to him, along with all of Hamdan, Abdul-Rahman’s maternal uncles, the reciters, and followers such as Saeed bin Jubair and Muhammad bin Saad bin Abi Al-Waqqas. Abdul-Rahman’s rising status greatly alarmed Abd al-Malik bin Marwan, who proposed to the people of Iraq to remove Al-Hajjaj. Abdul-Rahman's leadership over them caused great concern for Al-Hajjaj.[120]

Ibn al-Ash’ath's campaign lasted nearly four years, with Abdul-Rahman winning eighty battles against Al-Hajjaj’s armies. However, he was ultimately defeated in the Battle of Dayr al-Jamajim. Abdul-Rahman fled to the Turkish lands with Ubaid bin Abi Suba` al-Tamimi, but Al-Hajjaj sent Amara bin Tamim al-Lakhmi to capture him. Realizing he would be handed over to Al-Lakhmi, Abdul-Rahman chose to commit suicide rather than be delivered to the enemy in 85 AH.[121]

Talha bin Daoud al-Hadrami assumed the governorship of Mecca during the reign of the seventh Umayyad Caliph, Suleiman bin Abdul Malik. Bashir bin Hassan al-Nahdi held the governorship of Kufa and Basra, while Sufyan bin Abdullah Al-Kindi governed as well.[122] Ubadah bin Nasi Al-Kindi took over the governorship of Jordan during the reign of Omar bin Abdul Aziz, and Raja bin Haywa Al-Kindi was his advisor and the master of the people of Palestine.[123] During this time, Al-Samh bin Malik Al-Khawlani governed Andalusia, opening several forts. He was killed in the Battle of Toulouse in France and was succeeded by Abdul-Rahman Al-Ghafiqi, who was killed in the Battle of Balat al-Shuhada.[124]

Tribal disputes broke out throughout the country, particularly between the Yamaniyya and Qays Aylan, along with the Ta'i, Ghassan, Banu Amila, Lakhm, and other tribes of Rabi'ah. Marwan bin Muhammad, the last Umayyad caliph, was nicknamed "Donkey" due to his numerous wars. Homs, a major stronghold of the Yemeni tribes, revolted against him during this period of conflict. Abdullah bin Yahya al-Kindi also ruled in the year 128 AH, but he was not motivated by tribal loyalties. He was regarded as one of the major imams of the Ibadi and the judge of Ibrahim bin Jabla al-Kindi, the Umayyad governor in the later years of the dynasty. Abdullah dominated Hadhramaut and Sanaa, opened the treasury, and distributed the funds to the poor without taking anything for himself.[125] Abdullah's army, led by Al-Mukhtar bin Awf Al-Azdi, was able to storm Mecca, but they were defeated at a site called Jerash, and his forces returned to Yemen.[126]

Yemeni mini-states

[edit]

Some Yemeni tribes supported the Abbasid call at its beginning.[127] The country became independent from the Caliphate in 815, and several states were established throughout Yemen for sectarian and tribal reasons. The State of Bani Ziyad, founded by Muhammad bin Abdullah bin Ziyad Al-Umawi, was established in 818. It was nominally subordinate to the caliphate in Baghdad, and its influence extended from Hilli bin Yaqoub south of Mecca, passing through Michalaf Jerash (Asir), and even to Aden. Zubaid in Al-Hudaydah was made their capital.[128] Meanwhile, the State of Banu Yaafar, founded by Yafar bin Abd al-Rahman al-Hawali (a Himyari),[129] was established in 847 in Sanaa, covering the surrounding countryside, Al-Jawf, and the mountainous region between Saada and Taiz.[130] Saada fell into the hands of Imam Yahya bin Al-Hussein in 898.[131]

Mawla Hussein bin Salama was able to preserve the state of his masters, Bani Ziyad, and confront Abdullah bin Qahtan Al-Himyari. However, Al-Himyari managed to burn Zubaid.[132] Ibrahim bin Abdullah bin Ziyad, the last prince of the Ziyad family, was killed by his loyalists, Nafis and Najah, who went on to establish the State of Bani Najah on the ruins of the Ziyad state in Tihama. They enjoyed support from the Caliphate center in Baghdad.[133]

The Ibadis established several states for themselves in Yemen, and large parts of Hamdan and Khawlan pledged allegiance to Imam Yahya bin Al-Hussein. Ali bin Muhammad al-Sulayhi, the founder of the Sulayhid state, opposed the Zaidi Imams and the Najjahis in Tihama, as well as various tribal forces in Saada. He fought many battles and was able to bring most of Yemen under the rule of a single state, a first since the advent of Islam. He made Sanaa the capital of the country.[134]

In 1064, Ali bin Muhammad al-Sulayhi annexed Mecca.[135] However, they did not attempt to impose their religious doctrine.[136] In 1138, Sultan Suleiman bin Amir al-Zarahi, the last Sulayhid sultan, died, and the regions became independent, including Sanaa, which was controlled by three families from Hamdan. Aden also became independent, with Banu Zurayi, from the Yam tribe of Hamdan, assuming control. Al-Mukarram Al-Sulayhi had appointed them over it.[137]

The Najjahs returned briefly to Tihama, but Ali bin Mahdi Al-Himyari eliminated them, imposed a specific lifestyle on them, and isolated them from society in 1154. This marked the beginning of the emergence of a group of modern-day Yemeni citizens known as the Akhdam.[138][139] Grudges between tribal leaders prevented them from unifying their stance against the Ayyubids[140] until the Zaidi tribes (Hashid, Bakeel, Sanhan, Khawlan etc.) defeated the Ayyubids in 1226.[141]

Omar bin Rasool established a state known as the Apostolic State, one of the strongest kingdoms Yemen had seen since the advent of Islam.[142] It was also one of the longest-lived Yemeni states in the country's history after Islam. The state built the Cairo Citadel in Taiz, along with a mosque and the Al-Muzaffar School.

The division between the Arab Arabs and the Arabized Arabs is rooted in what is mentioned in the Old Testament and is derived from the accounts of the beginning of creation. Later, genealogists and historians agreed to classify the Arabs into two main groups based on lineage: the Qahtaniyah, whose origins are in Yemen, and the Adnaniyah, whose origins are in Hijaz.[19][20]

The Mazhaj established a strong state, the Tahirid state, with their city of Radaa, but they did not submit to the Zaidi Imamate. The Tahirid army was defeated by Imam Al-Mutahhar ibn Muhammad in 1458.[143] Despite this, the Tahirids successfully repelled the Portuguese from Aden. By the late 15th century, Hadramaut had fallen to the Kathiriyya Sultanate. Imam Al-Mutawakkil Sharaf al-Din, with the commander of the Mamluk army, was able to defeat the Tahirids and drive them out of Taiz, Radaa, Lahj, and Abyan.[144] The fall of the Tahirid state was complete, although they retained control of Aden until 1539, when the Ottomans took control of Aden, then Taiz, Al-Hudaydah, and the rest of Tihama.[145]

The Ottomans' rule over Aden was one of the worst periods in the city's history. However, the Zaidi tribes, led by Imam Al-Mansur Al-Qasim, were able to defeat the Ottomans after several revolts were suppressed. Their success was due to their ability to effectively use firearms.[146] In 1644, they liberated Aden from Ottoman control, and Yemen became the first region to separate from the Ottoman Caliphate.[147] By 1654, the tribes of Hashid, Bakeel, Sanhan, and Khawlan extended their control over all of Yemen in favor of the Zaidi Imamate.[148]

An overview of the tribes

[edit]

The Kingdom of Sheba included many tribes mentioned in texts written in the Musnad script, though little is known about them. These include tribes such as "Fishan," "Dhu Ma’ahir," "Dhu Khalil," "Dhu Lahad," "Dhu Yazan," and many others. These tribes were not referenced in the writings of genealogists and historians. However, some tribes mentioned in historical sources that still exist today are Hamdan, Kinda, and Mazhaj, with the latter two historically identified as Bedouin tribes.

Hamdan

[edit]Hamdan refers to an ancient Sabaean land mentioned as early as the seventh century BCE.[149] According to historical sources, Hamdan is considered the ancestor of the Hashid and Bakeel tribes. Genealogists trace his lineage as Hamdan bin Malik bin Zaid bin Usala bin Rabi’ah bin Al-Khayar bin Malik bin Zaid bin Kahlan bin Saba.[150]

The primary deity of the Hamdan people was Talab Riyam, believed to be their divine ancestor and the son of the supreme Sabaean god, El-Maqh.[151] Ancient Musnad texts refer to Hamdan as "Ardam Hamdan," which translates to "the land of Hamdan."[152] The term "ardam" in this context likely refers to barren or dry land that does not support vegetation.[153]

Hamdan is divided into two main branches: Hashid and Bakil, both of which are large and prominent tribes. The earliest mention of Hashid, referred to as "Hashdum" in ancient Sabaean texts, dates back to the 4th century BCE.[154] In contrast, Bakil's earliest reference appears in the 6th century BCE.[155]

Since the 4th century BCE, the kings of the Kingdom of Sheba began to belong to one of the branches of Hamdan for reasons that remain unclear but may be uncovered through future archaeological discoveries.[156] The leader of Hashid, Yarim Ayman, successfully monopolized the kingdom around the second half of the 2nd century BCE.[157] Subsequently, kingship shifted to Bakil in the latter half of the 1st century BCE.

Bakil's control over the kingdom ended after the Himyarites, under the leadership of Dhamar Ali Yahbar I, triumphed in 100 CE.[158]

The Hamdan tribe primarily resides in Sanaa and its surrounding areas, with extensions in the Amran Governorate. Additionally, there are independent sheikhdom tribes, such as the Yam Tribe, located outside the borders of the Republic of Yemen. According to Western sources, Hashid and Bakil are described as alliances of several tribes or a "tribal union" comprising various clans. This practice reflects an ancient custom in the Arabian Peninsula, where larger tribes incorporate smaller ones under specific circumstances.

The term "Bakeel" is theorized to derive from the word "Yabakal," which signifies mixing or bringing together. Another interpretation suggests that Bakeel means "a beautiful man."[159] However, since the name appears in ancient Sabaean texts, it likely holds a distinct meaning tied to its Sabaean origins. There is no doubt that the name Bakeel is of Sabaean origin, and both Hashid and Bakeel are as ancient as the Kingdom of Sheba itself.[160]

Historically, the Hashid and Bakil tribes were referred to as the "wings of the Zaidi Imams."[161][162] However, this does not imply that all Hamdan members are Zaidi or that the Zaidi sect is exclusive to them. This connection is primarily from a historical perspective and does not represent the full diversity of beliefs within the tribes.

Although the 26 September Revolution originated in Taiz, a region where tribal influence is less pronounced compared to other Yemeni areas,[163] the Hamdan tribes played a significant role in supporting the revolution. This involvement granted them influence and power, enabling them to participate in shaping political decisions in the newly formed Yemen Arab Republic. Their influence extended beyond politics, providing opportunities for broader economic and commercial activities, which in turn impacted traditional cultural and social structures.

Some sources indicate that many families from the Hashid and Bakil tribes shifted their allegiances periodically, driven by political interests.[164] These tribes have remained among the most politically influential in the Republic of Yemen since the fall of the monarchy in 1962 and after Yemeni unification.[165]

Bakil is divided into four main sections: Arhab, Marhaba, Nihm, and Shaker. They are considered the most numerous of the Yemeni tribes, and many other tribes have joined their ranks, making them the largest tribal union in Yemen.[165]

However, Bakil is not under the influence of the Hashid tribe. This independence is attributed to the existence of multiple sheikhdoms within Bakil and the lack of centralized leadership under a single family.[165]

Kinda

[edit]

Kinda (Musnad: 𐩫𐩬𐩵𐩩) is an ancient Arab tribe first mentioned in texts dating back to the second century BCE.[166] This tribe is referred to in heritage books as the "Kings of Kinda."[167]

The Kingdom of Kindah was established in Najd,[168] though the history of this pre-Islamic kingdom is shrouded in ambiguity. Historical accounts from news writers provide some information, but much of what is known comes from writings discovered in Qaryat Al-Faw, recorded in the ancient Musnad script. These inscriptions serve as a more reliable source for understanding Kinda's history, avoiding the biases of lineage-related fanaticism and the subjective accounts of early historians.

Kindah is historically divided into three main sections: the Sons of Muawiyah, often referred to as "The Noble Ones" due to their status as the kings of Kindah,[169][170] along with Sukun and Sakasik. Over fifty tribes branch out from these divisions, with members of these tribes located in Yemen, the Sultanate of Oman, and the United Arab Emirates. Additionally, there are clans in Iraq and Jordan that continue to uphold and cherish their ancient lineage.

The oldest Sabaean texts referencing "Kinda" date back to the second century BC and place them in Najd.[171] The Musnad script texts describe Kinda and Madhhij as "the parsing of Sheba."[172]

Mazhaj

[edit]The oldest mention of the Mazhij tribe dates back to the second century BC.[173] They were part of the Kingdom of Kindah and were mentioned in the Al-Namara Inscription of the king of the The Kingdom of Al-Hirah. The texts of the Musnad script described them as "the Bedouins of Sheba."[174] Madhhij is one of the sections to which many tribes in Yemen and the rest of the Arabian Peninsula trace their origins, as well as several other countries that maintained their tribal connections. The tribe was known in Arab heritage books by the title "Mazhaj al-Ta'an."

Mazhaj is historically divided into three sections: the Saad clan, Ans, and Murad. They are found in most areas of Yemen and consist of many tribes. These include Nak' in Al-Bayda Governorate, Abyan, and Banu Al-Harith bin Ka'b in Shabwa, Ma'rib, and Sada’. Ubaida is found in Ma’rib and Al-Habbab from Qahtan, as well as Al-Minhali in the north of Hadramaut and Sanhan, around Sana’a. This includes the tribe of Ali Abdullah Saleh and Hakam in Tihama, the tribe Al-Had'a from Murad, and Al-Qaraada'ah in Ma'rib, also from Murad. Among them is Sheikh Ali bin Nasser Al-Qardai Al-Muradi, the killer of Imam Yahya Hamid Al-Din.

The Anas tribe is found in Dhamar, and one of its branches is Al-Ansi, which originally comes from Mazhaj but later entered Bakil, like many other tribes. There is also the Al-Riyashi tribe, with members in Al-Bayda Governorate and Al-Dhale’, also from Mazhaj. Some sources mention that they are from Kinda. Additionally, there are many tribes in Madhhaj, including the Al-Dulaim clans in the deserts of Iraq and Syria, who trace their origins back to Zubaid.

Himyar

[edit]He is the eldest son of Saba and the brother of Kahlan, according to reports.[175][176] Although the Himyarites were the ones who overthrew Saba and Hadhramaut and unified them into one state, there is no indication that the Himyarites were descendants of Saba. Ancient Sabaean texts refer to them as "the sons of a paternal uncle," and this uncle was the greatest god of the ancient Qataban kingdom, not Sheba.[177][178] They seized "Dahsum," which was the land of the Yafa and Al-Ma’afer tribes, and fought with Saba for a long time until they completely overthrew it around 275 AD.

There are many tribes attributed to Himyar in various parts of Yemen and beyond, and discussions about their divisions rely on the writings of the informants rather than the Musnad inscriptions. The Musnad texts do not mention that Himyar, or "Himyar," was a man with children, or that his real name was "Al-Arnaj." Instead, he was called Himyar because he wore a red robe.[179] Like Sheba, the Himyarites were an ancient ruling family. The tribes joined them in opposition to Sheba, and the informants considered them "Himyar tribes."[180]

The oldest text discovered about Himyar is a Hadhrami inscription referring to the construction of a wall around Wadi Labna in Hadhramaut. Its purpose was to prevent the Himyarites from attacking the caravans of the Kingdom of Hadhramaut, located between Shabwa and the port of Qena, and to block their encroachment on the Kingdom of Hadhramaut's territory toward the coast. The text dates back to the fifth century BC (around 400 BC).[181] The Himyarites established their government at the end of the second century BC, during a time when the Kingdom of Sheba was greatly weakened. As a result, the Himyarites swept through the central and southern regions of Yemen (present-day Yemen) and took control of Dhofar Yarim as their capital.[182]

The first mention of the Himyarites was Shammar Dhu Raydan, who fought many battles against Ili Sharh Yahudhab and allied with every enemy of the Sabaeans. However, he did not win and was eventually forced to reconcile with the King of Sheba. He then joined the Sheban army as a commander.[183] During this time, Himyar was divided, with some factions allied with Sheba, while others remained independent and did not recognize the authority of the weakening Sheban government. This led to the rise of four royal dynasties in Yemen: Hashid, Bakil, and two Himyarite dynasties. Each of these factions claimed the title "King of Sheba and Dhu Raydan."[184]

The turmoil continued for a century and a half, with some estimates suggesting that twelve Himyarite leaders arose during this period. Eventually, in 275 AD, the Himyarites were able to establish their kingship under the leadership of Shammar Yaharash.[185]

Hadhramaut

[edit]

Hadhramaut is the name of an ancient tribal union. Genealogists and informants sometimes referred to it as "the belly of donkeys," with some claiming that a man named "Amer bin Qahtan" would kill many enemies, leading them to exclaim "Hadhramaut" upon seeing him.[186] However, these narratives lack archaeological support or evidence. As such, Hadhramaut is not considered Himyarite; it predates the Himyarites.[187]

The Hadhrami tribes, including Siban, Noah, Al-Sadaf, and Al-Sa'ir, are among the ancient tribes of the region. Although no Musnad inscriptions have been discovered linking these tribes to Himyar, it is important to note that Siban and Noah are ancient tribes. Siban, for instance, is mentioned alongside Al-Mahra in a text written by Samifa Ashua Al-Himyari, though no chain of transmission is provided in the text. The description of these tribes as coming from Hadhramaut seems more accurate.[188][189]

Tribes such as Siban, Nuh, and al-Humum share closer features and clothing with the Mahra and the inhabitants of Socotra, indicating no direct relation to the Himyarites.

In general, Hadhramaut is considered somewhat less tribal than other regions in Yemen, despite the presence of tribes. In a study conducted by American researcher Sarah Phillips in cooperation with Sana'a University, 70% of the population in Hadhramaut declared that their loyalty should be to the state rather than to the tribe. This percentage was higher than that of the population in the Amran Governorate's Al-Ahmar Center.[190]

Quda'ah

[edit]The name "Qada'ah" or "Adnan" was not mentioned in ancient texts that predate Islam, and only a little about "Qahtan" was mentioned in the Musnad texts, but as a land name rather than in the form portrayed by the informants in the Umayyad and Abbasid eras.[191] Qada'ah includes many tribes, some of which are located in the south of Arabia, and some in the north. During the era of the Banu Umayyads, boasting among the Arab tribes began, with each tribe attributing others to its section, composing legends and satirical poems against other sections. This led to an escalation, with clients taking pride in the origins of their masters while mocking others.[192] The Battle of Marj Rahit was one of the most significant wars that fueled these grudges. The Yemenis sided with Marwan bin Al-Hakam, while the Qaysiyyah supported Abdullah bin Al-Zubayr.[193][194] The disagreement among informants and genealogists about "Quda'ah" stems from this boasting. The tribes considered "Quda’ah" are mentioned in Musnad texts without specific ancestors, but rather as peoples. Among these tribes, the most prominent is Khawlan, which was mentioned as "Khulan" and "Dhi Khawlun," along with other "Qada'i" tribes such as "Kalb" (Banu Kalb), "Nahd," and "Adhrat" (Adhrah), but there is no mention of a single tribal bloc called "Quda'ah."[195]

Yafa'a

[edit]Yafi' is a tribe belonging to Himyar bin Saba',[196][197][198] and their land was known in the texts of Al-Musnad as "Dahs" or "Dahsam," later named after them during the era of the Upper Yafa Sultanate.[199][200][201][202] The Yafi' tribe in the Yafa region is divided into two main sections: Banu Qasid and Banu Malik.[203][204] They established several sultanates throughout history in Yemen and abroad, such as the Tahirid State,[205] the Emirate of Al-Kasad,[206] the Qu'aiti Sultanate,[207] the Emirate of Al-Buraik,[208] and others.[209]

Outside the Yafa' area, the tribe is usually divided into three major clans: Al-Mousta, Al-Dhabi, and Banu Qasid. Collectively, they are referred to as Ayal Malik or Banu Malik, in reference to Yafa' Na'ta's grandfather, who was nicknamed Malik. They are spread across almost all governorates of Yemen, especially in Hadramaut.[210][211][212] The Yafa' tribe was also notable for being among the first to embrace the Najdi Salafi call in Yemen during the era of Imam Muhammad bin Abdul Wahhab.[213][214]

Yafa' played a role alongside other tribes in the October 14 Revolution against the British colonizer. However, unlike the northern regions of the country, the revolution and the expulsion of the colonizer did not strengthen the influence of the tribes; instead, it increased their weakness and disintegration, with minor differences from one southern governorate to another. This was due to the policies of the Yemeni Socialist Party, which seized power after the expulsion of the British colonialists from Aden. The Socialist Party made weakening tribal influence one of its priorities.[215] However, tribal (or more precisely, regional) affiliations resurfaced during the 1986 civil war, with divisions between supporters of Abdul Fattah Ismail and Ali Nasser Muhammad.[216]

al-Aulaqi

[edit]The Aulaqi is one of the largest and most influential tribal blocs in the south of Yemen.[217] They are a tribal confederation from Shabwah Governorate in the eastern desert of Yemen. Most of the families in the confederation trace their origins to Himyar, Kinda, and Mazhaj. The Aulaqi appeared under this name in the late eighteenth century. They established several sultanates in the modern history of Yemen, including the Upper Aulaqi Sultanate, the Lower Aulaqi Sultanate, the Al-Daghar Sultanate, and their sheikhdom in Al Farid. Compared to other tribes in the south of Yemen, the Aulaqi is a more cohesive tribe, and they are primarily located in Shabwa.

Traditional tribal structure

[edit]The tribal structure in Yemen can be classified into several organizational levels: the tribal union, the tribe, the clan, and the house. While this is an academic classification, in daily usage, the term "tribe" is often used interchangeably to refer to the tribal union, the tribe, and the clan.

When comparing the tribal division with Yemen’s administrative division, the "tribal union" typically spans across several governorates. The "tribe" generally aligns with a district, although it sometimes encompasses multiple districts or shares a district with other tribes. The "clan" corresponds to a subdistrict or community level, while the "house" aligns with a village.

Many Yemeni villages include the term "house" (e.g., Beit Al-Ahmar in Sanhan), reflecting both a spatial or administrative connection and a shared kinship bond.[218]

Although genealogical studies often assert that lineage is the fundamental bond within society at various levels, this generalization is inaccurate. Numerous political and economic factors have influenced the formation and restructuring of tribal unions, often through systems of allegiance rather than strict kinship.[219]

For instance, some tribes have separated from the Mazhaj tribal union to join the Hashid or Bakil tribal unions.[220] As a result, the bond at the level of the "tribal union" is primarily based on loyalty rather than lineage. At the tribal level, the connection is often driven by shared interests, as the tribe functions as an organization for managing natural resources.

However, at the levels of the clan or house, kinship remains the primary bond, typically encompassing individuals related through kinship up to the fifth, sixth, or even seventh generation.[221]

Social structure

[edit]Historically, the Yemeni tribe functioned as an independent political and economic unit. It served as an organization for managing collectively owned natural resources, a military unit responsible for defending its members and affiliated individuals or groups, and a social system that regulated relationships within the community.

The social status of individuals within the tribe, as well as the relationships governing their daily interactions and social behaviors, was determined by their roles in producing and protecting the tribe’s economic needs. According to Khaldun al-Naqib, the tribal economy in the Arabian Peninsula was primarily an economy of conquest. Consequently, individuals tasked with protecting the tribe held a prestigious position within its structure.

The tribe was not exclusively composed of individuals sharing a common lineage. Others could join either voluntarily, through the system of fraternization (as seen in the relationships among early Islamic Companions), or forcibly, through the annexation of war prisoners. Those who joined voluntarily through fraternization were granted equal status with the tribe’s original members, provided they contributed to its defense and paid the required "fine" (a form of tribute or obligation).[222]

The Yemeni people have inherited ancient social traditions and customs that date back to pre-Christian times, reflecting deeply rooted social patterns and roles.[223] In ancient Yemen, the Makariba or soothsayers were held in great veneration and respect, as they represented the religious authority of the community.

In tribal society, the fundamental unit of interaction was the family rather than the individual. The Sayyidah and Hashemites enjoyed a high social status among the tribes with which they were associated. Their primary role was to mediate conflicts between tribes. Additionally, a well-established tribal custom obligated tribes to protect their neighbors. The Sayyidah, being non-combatants, did not fight or carry weapons and lived under the protection of the tribes.[224]

The next social class is composed of sheikhs or judges, who are of tribal origin but often do not carry weapons.[225] Below them is "the tribe," which typically consists of individuals who bear arms and may engage in agricultural work, although they generally avoid manual or craft labor. In reality, "the tribe" is considered the highest social class, and the status of the sheikhs and judges depends on the approval and support of the tribes.[226]

Lower social classes included craftsmen and artisans, such as the Muzayna (circumcisers, barbers, and cuppers), the Qashamen (vegetable sellers and owners of stalls and carts), and the Dawasheen (those who recited welcome poems and sang Al-Zamil). Despite their lower status, these groups were afforded protection by the tribes due to the essential nature of their services.[227]

Distribution of power

[edit]

The distribution of power in traditional Yemeni tribal society followed a hierarchical structure aligned with the tribal organization. In the Hashid tribes, the "Sheikh of the Sheikhs" stood at the top of tribal authority, followed by the "Sheikh of Al-Daman," then the sheikhs, headmasters, and secretaries.

In the Bakil tribal confederation, leadership similarly began with the "Sheikh of Sheikhs," followed by tribal heads known as "Captains,"[note 1] then the sheikhs, elders, and trustees.

In the tribes of Hadhramaut, each group was led by a tailah, while each tribe was headed by a colonel.[note 2] Leadership within subgroups, or "thighs," was managed by an "intruder." The term sheikh in Hadhramaut was reserved exclusively for religious leaders and scholars.

Those holding the ranks of "Sheikh of Sheikhs" and "Sheikhs of Al-Daman" in the Hashid tribes, along with their counterparts in other tribes, constitute the elite and the political authority within the tribe.[228]

In Islamic historical writings, they are often referred to as the “People of Solution and Contract.”[229] These leaders are authorized by their tribes to negotiate and conclude treaties, agreements, and alliances with the state and other tribes or to dissolve them. They also serve as representatives of the tribe in dealings with the state and other tribal entities.

Those holding the third rank in the tribal power hierarchy, referred to as "sheikhs" or their equivalents, form the military elite of the tribe. They are responsible for mobilizing tribal fighters and leading them during conflicts and wars.

Next in rank are the "aqal" (elders) and secretaries, or their counterparts. They constitute the executive authority within the tribe. Their duties include collecting zakat, implementing directives issued by higher-ranking leaders, summoning individuals for tribal obligations, documenting agreements, and supervising tasks such as the distribution of irrigation water, among other responsibilities.[230]

Despite variations in tribal authority structures among different tribal unions, a common feature across all of them is that positions of tribal authority were chosen by members of the tribe, either directly or indirectly. In the Al-Fadhli region, for example, sheikhs were selected by members of their tribes.[231] The same applied to the Al-Wahidi Sultanate and the Al-Fadhli tribes in Abyan. In some tribes, such as the "Ibn Abd al-Mani" tribe, the position of sheikh rotated among its three divisions.

In the Hashid and Bakil tribes, sheikhs were historically chosen through the endorsement of village sheikhs and headmen. However, in modern times, the position has become hereditary, with the title passing to the eldest son after the father's death.[232][233] In Hadhramaut, leaders known as "presenters" were chosen through consultation and consensus among the "intruders" of the tribes, with their installation taking place at a meeting called the "Intruders’ Meeting."

In traditional tribal society, the sheikh was subject to accountability by the tribe and could be replaced if found to be arrogant or tyrannical.[234]

The selection of those holding the first rank, the "Sheikh of Sheikhs," has traditionally been conducted through a mechanism resembling the system of allegiance.[235] For instance, Sheikh Sadiq al-Ahmar was pledged allegiance in 2008 as the successor to his father, Abdullah al-Ahmar. Similarly, Sheikh Sinan Abu Lahoum was installed as the Sheikh of Sheikhs of the Bakil tribal confederation in 1977, with his son succeeding him in the same manner during a tribal conference in 1982.

The politicization of the social authority of tribal sheikhs had negative effects on both the state and the tribes. At the tribal level, it led to a transformation from an egalitarian structure to a hierarchical one, shifting social authority from being based on acceptance to becoming compulsory. This also weakened social relations within tribes, as tribal sheikhs no longer represented their tribes before the state but became representatives of the state in their regions. As a result, they were no longer accountable to their tribes, which contributed to the erosion of the intermediary space between the state and society.[236]

At the state level, the politicization of tribal sheikhs' social authority helped give the state the characteristics of a sultanate, undermined its ability to enforce the law, and contributed to the sharing of state power between the tribe and the government. This weakened the government's capacity to monopolize political power.[237]

Social relations

[edit]Social relations in Yemeni tribal society were characterized by a collective nature. The unit of dealing was the family, not the individual, and ownership of pastures and natural resources was considered collective property. Individual disputes often escalated into collective conflicts.[238] The Yemeni tribes developed a customary justice system for arbitration, focusing on settlement and reconciliation rather than punishment.[239] In the tribe, no authority was authorized to impose punishment on offenders.[240] Tribal sheikhs acted as arbitrators between tribes, not as judges over them. As a result, the phenomenon of revenge spread among the Yemeni tribes. Revenge was not taken directly from the killer, but from any member of the clan to which the killer belonged.

Each Yemeni tribe has a "diwan," which serves as a middle space between the tribe and the state, as well as a public space for deliberating on general tribal issues. It is where decisions related to resource management are made and disputes between families and clans[241] are settled through a consensual process among tribe members.

Recently, the tribe's decision-making process is no longer carried out through consensus. Instead, the sheikh makes most of the decisions without referring to the tribe's members. This shift has stripped the tribe of its traditional civil character, strengthened its sectarian nature, and hindered the development of a modern civil society.

Marginalized groups

[edit]

In the past, society looked down on singers, but this has changed recently. Many of the Yemeni singers who have emerged belong to different societal groups, including the lowest strata, known as the Marginalized.[242][243] These customs no longer have their previous effect or remain only symbolic. However, discrimination, marginalization, and contempt for the so-called Akhdam or marginalized people persist, even leading to physical attacks and neglect by the authorities. The tribal structure in Yemen continues to exist.[244][245]

The situation of the Akhdams in Yemen is similar to that of the Pariha in India.[246] Al-Akhdam are often confused with slaves, but they are not slaves or mamluks, nor have they ever been. These social divisions existed in both North and South Yemen under different names. The equivalent of "judges" in North Yemen (such as the late Ibrahim al-Hamdi) are referred to as "Sheikhs" in the south and Hadramaut. These divisions have ancient roots dating back to the history of Ancient Yemen.

In Aden, things were different. Aden has long been a commercial city,[247] visited by merchants, and it was unclear who its original inhabitants were. In 1872, the city's population was 19,289, of whom 4,812 were Arabs, 965 were original inhabitants,[248] and 8,168 were Indians, including 2,557 Muslims, with the rest being Africans from East Africa.[248]

On the religious level, intermarriage between Zaydis and Shafi'is is common in Yemen.[249] Ismailis tend to intermarry among themselves, while there is a very small Twelver minority, whose existence is not officially recognized by the Yemeni government, and they suffer from societal isolation.[250] Intermarriage between Yemeni Jews is socially rejected, primarily for religious reasons. Yemeni Jews even refuse to marry their daughters to Muslims, but they are too socially and legally weak to prevent such marriages.

Before Islam, intermarriage with Jews was common in Yemen. Yemeni Jews are a mix of Hebrews and local tribes,[251] and their presence in Yemen is ancient. They are the indigenous people of Yemen and do not differ from the tribes ethnically or racially, except for their religious beliefs and culture. However, Yemeni Jews face societal and political discrimination and marginalization, as noted by Orientalists who visited Yemen in the 20th century.

The Jews of Yemen have a long and rich history that traces back to ancient times. Historically, they were known for their craftsmanship, particularly as skilled goldsmiths and exceptional makers of daggers. Their expertise in these crafts was highly regarded, and they played an important role in the local economy and culture. Their presence was particularly strong in Aden, which was a major commercial port, attracting traders and travelers from all over the world, including the British during their colonial rule.[246] However, with the establishment of Israel in 1948 and the subsequent political and social changes, the majority of Yemeni Jews emigrated, primarily to Israel and the United States. A smaller number of Jews remained in Yemen, but their influence—both socially and politically—diminished significantly over time.

Yemeni Jews, despite their deep historical roots in the country, faced societal discrimination due to their religious beliefs and cultural practices. This marginalized them, but they continued to contribute to the cultural and intellectual landscape of Yemen. Many Yemeni Jewish scholars were involved in various fields such as medicine, industry, and language, producing works that enriched local knowledge. Yet, despite their intellectual contributions, their social status was often low, and they were subjected to the discriminatory practices that were prevalent in Yemeni society.

In contrast to the marginalized status of Jews and other minority groups, Yemeni society also includes individuals of Turkish and Persian origins, who have generally been better integrated into the social fabric. Yemen’s history of imperial influence, particularly from the Ottoman Empire, led to the presence of many Turkish individuals who became part of Yemen's elite, assimilating into various aspects of Yemeni life. The same cannot be said for those of African origin, including the Muhamasheen (also known as Al-Akhdam), who continue to face systemic discrimination.[252]

The discrimination against the Muhamasheen is particularly severe. They make up a significant portion of Yemen's population, estimated between 500,000 and 1 million people, and are often treated with contempt by other groups. Their social and political exclusion remains a persistent issue, despite efforts to address it. One notable attempt to include the Muhamasheen in the political process was during the Yemeni National Dialogue Conference, where a representative, Noman Al-Hudhaifi,[253] was appointed to speak on their behalf. However, their representation and influence within the national dialogue were minimal, reflecting the continued marginalization of this community.

The difficult economic conditions in Yemen have contributed to some degree of melting social differences, but this has not been uniform across all tribal groups. Tribes surrounding the capital, Sanaa, including Amran and Sanhan, often saw themselves as key participants in the political processes, especially during the rule of Ali Abdullah Saleh. However, the country remains deeply divided along tribal, ethnic, and social lines, with the Muhamasheen continuing to struggle for recognition and equal rights in Yemen's social and political systems. The persistence of such divisions highlights the challenges Yemen faces in building a more inclusive and egalitarian society.[254][255]

Political role

[edit]Throughout the history of the modern state and earlier periods, the Yemeni tribe has held significant political importance in shaping the state. It constitutes a core part of the state's authority and plays a substantial role in political decision-making. However, while the tribal system exerts influence in opposing or halting decisions that conflict with its interests, it does not necessarily possess a vision for social transformation.

The expansion and prominence of the tribal role in Yemen have reinforced tribal structures, perpetuating a culture of exclusivity and unequal citizenship. This dynamic has remained a central issue in the conflict between modernization forces and traditional elements in Yemeni society. The dominance of tribal structures undermines efforts toward building a more inclusive civil society, limiting its capacity to contribute meaningfully to democratic transformation.

Traditional tribal forces, being inherently conservative, resist change and reforms, further entrenching the existing social and political status quo. This resistance has hindered progress toward social equity and democratic development, creating ongoing challenges for Yemen's modernization and reform efforts.

The tribe serves as a fundamental element of social capital and an active economic force. Its influence significantly impacts the relationship between the state and the tribe, shaping the degree of the state's institutionalization, its capacity to formulate and implement decisions, and its ability to uphold the rule of law.

The tribe in Yemen is regarded as a national entity by those advocating for its preservation in its current form. It is considered a significant and ancient component of the Yemeni people. Observers believe that Ali Abdullah Saleh utilized the tribal system to undermine civil values, effectively placing civil society under the control of tribal sheikhs. Over his 33-year rule, Saleh's regime did little to establish the foundations of a civil society.[256]

To enhance the regime’s image, Saleh exaggerated the role and nature of Yemeni tribes to gain legitimacy in the eyes of the international community.[257] Researcher Sarah Phillips suggests that the egalitarian nature of the Yemeni tribes might create the impression that democracy in Yemen could thrive more easily than in other Arab nations, as tribes prevent the rise of absolute authoritarian rule. However, in practice, Saleh leveraged the tribal system to reinforce minority rule and consolidate his power.[258]

In the south and Hadramaut

[edit]

After Captain Stafford Haines occupied Aden on 19 January 1839, he implemented a policy aimed at inciting inter-tribal conflicts to minimize the need for a substantial British military presence.[259] This policy was approved by the occupation government.[260] Haines and his successors successfully fragmented southern and eastern Yemen into multiple tribal entities, including sheikhdoms, sultanates, emirates, and states. By the height of this strategy, there were 25 such tribal states, all bound by protection agreements with the colonial administration in Aden.[261]

When the South gained independence in November 1967, the new state sought to dismantle the authority of tribal sheikhs and unify the tribal states into a single national entity. Consequently, the tribal structure played no significant political role. The policies of the Yemeni Socialist Party were instrumental in establishing state control and suppressing tribal authority in the southern regions before Yemeni unification in 1990.

The ruling party successfully built a centralized state with control over income sources. However, it was a closed totalitarian regime marked by poor relations with most neighboring countries and significant economic failures. In Hadhramaut, tribal authority was at its weakest in the South due to socialist policies and the extensive Hadrami diaspora in Southeast Asia, East Africa, and the Gulf. The population of Hadramis abroad far exceeded those within Hadramaut, contributing to the tribe’s diminished influence.

Nonetheless, tribal power remained stronger in southern regions such as Abyan and Shabwa. In Al-Dhalea, tribal influence grew to some extent after Yemeni unification and the Summer War of 1994, but it has never matched the strength and influence of the northern tribes.[262]

The state formed in northern Yemen after the 26 September Revolution sought to integrate tribal sheikhs into its political structure. However, the Yemeni state in the north, prior to unification, experienced a persistent power struggle between the military forces and tribal sheikhs.

Ali Abdullah Saleh, who neither belonged to a powerful tribe nor had extensive military experience, initially managed to create a balance and reconciliation between the tribal forces and the military at the start of his rule. Over time, however, his approach shifted. Saleh gradually restructured the military, transforming it into what could be described as a "family sector," consolidating his power and diminishing the independence of both the tribal and military forces.[263]

Yemen Arab Republic

[edit]Judge Abdul Rahman al-Eryani assumed the presidency following the dismissal of Abdullah Al-Sallal. While al-Eryani and others from his background did not wield the same tribal influence as the tribes surrounding Sanaa, the elites from his governorate, such as the Al-Eryani family, understood the importance of maintaining good relations with the tribal elites. This was due to their lack of a strong tribal base to support them, making alliances with influential tribal figures essential for their political stability.[264]

During the presidency of Judge Abd al-Rahman al-Iryani, the military became actively involved in political disputes, beginning with the conflict over the establishment of the National Council.[265] This period saw the armed forces propose what became known as the "correction decisions," which included demands to halt state funds provided to tribal sheikhs.

In August 1971, the government resigned, with Prime Minister Ahmed Mohamed Noman citing the administration's inability to fulfill its obligations due to the excessive depletion of the state budget by tribal sheikhs.[266][267][268] Similarly, in December 1972, the government of Mohsen Al-Aini also resigned. Al-Aini's resignation stemmed from unfulfilled demands, including the dissolution of the Shura Council dominated by sheikhs, the disbanding of the Tribal Affairs Authority, and the cessation of state-funded budgets allocated to tribal leaders.[269]

The June 13 Corrective Movement, led by Lieutenant Colonel Ibrahim al-Hamdi, marked a significant shift in Yemen's political landscape. President al-Hamdi overthrew Judge Abd al-Rahman al-Iryani by strategically persuading tribal leaders and temporarily leveraging their influence, recognizing their power on the ground. He initially sought the favor of Sinan Abu Lahoum by appointing his relative, Mohsen Al-Aini, as head of government and retaining Abu Lahoum's relatives in the military. However, al-Hamdi soon marginalized them.

Al-Hamdi worked to diminish the influence of tribal sheikhs in both the military and the state. He abolished the Ministry of Tribal Affairs, froze the constitution, and dissolved the Shura Council. On July 27, 1975, during "Army Day," he issued decisions removing numerous tribal sheikhs from military leadership. Although he distanced himself from Abdullah bin Hussein al-Ahmar, who opposed Abu Lahoum, al-Ahmar recognized al-Hamdi's intent to reduce the tribal forces' negative influence.[270] Angered by these efforts, al-Ahmar attempted to rally his supporters in the countryside near Sanaa to overthrow al-Hamdi. However, Saudi Arabia, a key supporter of Yemen's tribal forces through its "Special Committee" funding,[271] declined to support al-Ahmar. Al-Hamdi had successfully convinced Saudi Arabia that he was their ally by sidelining the Abu Lahoum family.[270]

During his presidency, al-Hamdi implemented significant political and economic reforms.[272] He relied on his popularity to steer Yemen away from Saudi dominance by curbing the power of influential tribal figures.[273] He held a summit with countries of the Red Sea Basin, initiated discussions with Salem Rabie Ali, the President of the People's Democratic Republic of Yemen, on Yemeni unity, and secured arms deals with France.[274] Tragically, al-Hamdi was assassinated in 1977, just one day before his planned trip to Aden to discuss unity with President Salem Rabie Ali.[275]

After the assassination of Ibrahim al-Hamdi, Ahmed Hussein al-Ghashmi assumed the presidency. Tribal sheikhs, including Lieutenant General Hassan al-Omari, Mujahid Abu Shawarib, Abdullah al-Ahmar, and Sinan Abu Lahoum, demanded positions within the armed forces.[276] These demands were met, resulting in the structuring of military units based on tribal and regional affiliations.[276]

The period of Ali Abdullah Saleh

[edit]In the 1980s, Ali Abdullah Saleh established the Tribal Affairs Authority to strengthen the influence of tribal sheikhs in power. This authority effectively reinstated the role of the Ministry of Tribal Affairs, which had been abolished by the late President Ibrahim al-Hamdi, and was tasked with organizing the distribution of funds to tribal leaders.[277]