Traditional Chinese medicine: Difference between revisions

| Line 157: | Line 157: | ||

===Acupuncture, moxibustion, and auriculotherapy=== |

===Acupuncture, moxibustion, and auriculotherapy=== |

||

[[File:Acupuncture1-1.jpg|thumb|200px|Needles being inserted into a patient's skin.]] |

[[File:Acupuncture1-1.jpg|thumb|200px|Needles being inserted into a patient's skin.]] |

||

[[File:Accupuncture and moxing.jpg|thumb|right|300px|Accupuncture and Moxibustion]] |

|||

[[Image:A Dose of Moxa.jpg|thumb|200px|Moxibustion]] |

[[Image:A Dose of Moxa.jpg|thumb|200px|Moxibustion]] |

||

[[File:Kyutoshin.JPG|thumb|right|300px|Accupuncture and Moxibustion after Cupping]] |

[[File:Kyutoshin.JPG|thumb|right|300px|Accupuncture and Moxibustion after Cupping]] |

||

Revision as of 17:16, 5 March 2011

Template:Contains Chinese text

| Part of a series on |

| Alternative medicine |

|---|

|

Traditional Chinese medicine (中医, pinyin: zhōng yī), also known as TCM, includes a range of traditional medicine practices originating in Asia, primarily in regions that are now part of China and Taiwan. TCM is a common part of medical care throughout East Asia, but is considered a complementary and alternative medical system (CAM) in much of the Western world. TCM therapy largely consists of Chinese herbal medicine (use of plants, human and animal parts, and minerals to make medicines), acupuncture (insertion of needles in the body), tuī-nǎ massage, and dietary therapy. Traditional Chinese medicines play a major role in Chinese lifestyle that is substantially different than the role of medicines in the west. They are part of everyday and social life in Chinese society.

Traditional Chinese medicine theory is based on ancient Daoist philosophical and religious conceptions of balance and opposites (yin and yang), and other metaphysical belief systems. In evidence based medicine, disproved theories are "continually being replaced with new ones", but in traditional Chinese medicine little has changed since antiquity and “the most current medical knowledge always had roots centuries old”.[1] Chinese knowledge of the human body was based not on anatomical studies using dissection, but on an “alternative anatomy”[1] based on astrological calculations and “complex associations with gods”.[1][2] Ill health is believed to result from an imbalance between what are believed to be interconnected organ systems, with one organ system believed to weaken or overexcite others. TCM practitioners believe that plant and animal products, and minerals can be used to stimulate or calm particular systems and bring them into balance. It is believed that insertion of needles in points of the body (acupuncture) and burning points of the body (moxibustion) stimulates the systems directly along what TCM believes are metaphysical flow lines of qi "energy", and that these can also be stimulated by practices such a special kind of massage and exercise. Astrological influences are also believed to affect qi flow in the body, e.g., the alignment of homes with the planets and stars, and the year, month, day, and hour of birth.[1][2][3][4]

TCM has been subject to criticism regarding a number of issues: its lack of scientific basis[1], its questionable effectiveness[4], its medicines containing toxins,[5][6][7] its being used instead of proven science based medicines,[8][9][4] possible side effects of its treatment methods, the ecological impact on endangered species by creating a black market demand for ineffective medicines made from animal parts[10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21], and the superstitious beliefs it promotes.[4]

Basic beliefs about the body and disease

TCM’s “alternative anatomy” and physiology is not based on dissection as in evidence based medicine, but is determined by complex associations with gods and divine will, Chinese astrology using “inauspicious dates” and relationships between astrology and medical procedures, deducing anatomy through speculation and hazy recollections of past experiences, and on metaphor, with mystical numerical associations such as that the number of arms and legs matched the number of seasons and directions, that the “five” organs correspond to the “five” planets, that the 12 blood and air vessels thought to exist correspond to the 12 rivers flowing toward and ancient Chinese kingdom, and that the 365 acupuncture points located on the the body correspond to one for each day of the year. TCM uses “imaginary organ systems” and disregards organ shape and location. Internal organs were not thought to have distinct physiological functions as in evidence based medicine.[1][2][22]

Blood flow is believed to be caused by self propulsion via supernatural qi energy, not by mechanical pumping of the heart.[1][22][1][2]

Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) is based in part on the religion of Daoism, with a belief that all parts of the universe are interconnected.[23] Traditional Chinese medicine teaches that illness is caused by an imbalance of metaphysical forces called yin and yang in the "imaginary organ systems", belived to be caused by a blockage or stagnation of a supernatural energy called "qi", or by external events such as the day and time of birth, weather, or alignment of the house with the heavens, whereas in evidence based medicine ilness is typically caused by germs, such as bacteria and viruses, or genetics.[1][24][4][2] An eminent practitioner writes about the cause of bleeding from the mouth and nose in the Journal of Chinese Medicine -

"Liver fire rushes upwards and scorches the Lung, injuring the blood vessels and giving rise to reckless pouring of blood from the mouth and nose."[25]

The vessels in which blood is believed to flow are anatomically incorrect, and the meridians in which qi is believed to flow do not correspond to any anatomical structure; no force corresponding to qi (or yin and yang) has been found in the sciences of physics or human physiology.[1][4][26][24][3]

Traditional Chinese Medicine: Practices

Traditional Chinese medicines

Traditional Chinese medicines are made from plant parts, human parts, animal parts, and minerals. These parts are typically compbined into a medicine, which is often made into a tea.

Chinese herbal medicine plays a special role in everyday and social life in China, so plays a different role than medicines in western science based medicine. In China, herbal medicine plays a large role in the everyday health care system, along side Western medicine, where it is considered the primary therapeutic modality of internal medicine.[27]. Chinese medicinals are now used world-wide under a belief by TCM practitioners that they treat many internal medicine complaints and diseases.

Snake oil is likely the most widely known outside of Asia[28][29], but ginseng is the most broadly used substance for the most broad set of alleged cures. Powdered pre-calcified antler, horns, teeth, and bones are second in importance to ginseng, with claims ranging from curing cancer to improving immune system function to curing impotence.

TCM medicines are associated with unproven claims of efficacy and are readily available; they are often mixed together and made into teas that may be toxic.[30] Some TCM medicines have been found to have adverse effects.[31][32] TCM herbs may contain toxins.[33][34] Potentially toxic and carcinogenic compounds such as arsenic trioxide and cinnabar are sometimes prescribed as part of a medicinal mixture.[35] A medicine called Fufang Luhui Jiaonang (复方芦荟胶囊) was taken off UK shelves in July 2004 when found to contain 11-13% mercury.[36] Many Chinese herbal medicines are marketed as dietary supplements in the West, whereby they are exempted from some testing requirements.[37]

Herbalists have used different names for the same ingredient depending on location and time, while ingredients with different medical properties have shared similar names. For example, mirabilite/sodium sulphate decahydrate (芒硝) was mislabeled as sodium nitrite (牙硝),[38] resulting in a poisoned victim.[39][40] In some Chinese medical texts, both names are interchangeable.[41]

Plants are more commonly used than animals and minerals in the medicines.[42] In the classic Handbook of Traditional Drugs from 1941, 517 drugs were listed - 442 were plant parts, 45 were animal parts, and 30 were minerals.[43]

There is a concern by conservationists about ecological impacts of the use of rare or endangered species.

Traditional Chinese medicines made from animals and human parts

Snake oil is likely the most well known Chinese medicine outside of Asia,[28][29] due to broad claims of conditions it was to treat. The use of animal parts from rare or endangered species popularized knowledge of traditional Chinese medicine outside of Asia. Chinese Animal parts corresponding to human parts, and using animal predispositions corresponding to human dispositions, are sold to remedy those human parts and predispositions, e.g., selling tiger's penis for impotence. Powdered pre-calcified antler, horns, teeth, and bones are of great importance, with claims ranging from curing cancer to improving immune system function to improving virility. Use of rare and endangered species has drawn criticism from conservationists.

Snake oil

Snake oil is the most widely known Chinese medicine in the west, due to extensive marketing in the west in the late 1800s and early 1900s, and wild claims of its efficacy to treat many maladies.[28][29] Snake oil is a traditional Chinese medicine used to treat joint pain by rubbing it on joints as a liniment.[28] It is claimed that this is “plausible” because oils from snakes are higher in eicosapentaenoic acid than some other sources. But there are no replicated studies showing that rubbing it on joints has any positive effect, or that drinking it in sufficient quantity to get an effect from the acid is not dangerous because of the many other compounds in the oil.[28][29]

Dried human placenta

Human placenta is believed to be sweet, salty, and warm, so it is dried and believed to treat impotence, infertility due to cold sperm or deficiency, and female infertility because of uterine coldness, chronic cough, asthma, and insomnia, and marketed as such[44][45][46][47][48][49]

Flying squirrel feces

Flying squirrel feces is used raw in a belief that it will "invigorate" the blood and dry-fried in a belief that it will stop bleeding.[44][45][50][46][47][49]

The text Chinese Medical Herbology and Pharmacology notes that flying squirrel feces has a "distinct odor" that "may decrease patient compliance" with ingesting it.[51] Flying squirrel feces has been associated with typhus fever.[52]

It is believed to have uses for amenorrhea, menses pain, postpartum abdominal pain, epigastric pain, chest pain.[45] It is boiled in a decoration with other herbs prior to ingestion. If it is to be used in a formula to stop bleeding (dark purple uterine bleeding with clots, retained lochia due to stasis), it is dry fried prior to making the decoration.[44][45][46][47][49][53]

Tiger's penis

Popular "medicinal" tiger parts from poached animals include tiger penis, believed to improve virility, and tiger eyes.[10][11] Laws protecting even critically endangered species such as the Sumatran Tiger fail to stop the display and sale of these items in open markets.[12]

Ass-hide glue pellets

Glue made from the hide of donkeys is made into pellets for use in making teas.[30]

Toad secretions

Toad (Bufo spp.) secretinons are an ingredient used in Traditional Chinese teas and have been found to be highly toxic and possibly lethal.[30]

Rhinoceros horn

Endangered rhinoceros horn is used as an antifever agent, because it is believed to "cool the blood".[13] The black market in rhinoceros horn decimated the world's rhino population by more than 90 percent over the past 40 years.[14]

Shark fin soup

Shark fin soup is traditionally regarded as beneficial for health in East Asia, and its status as an "elite" dish has led to huge demand with the increase of affluence in China, devastating shark populations.[15]

Turtle shell

Widespread medicinal use of turtle plastron is of concern to conservationists.[16]

Seahorse

Seahorse fish is a fundamental ingredient in therapies for a variety of disorders, including asthma, arteriosclerosis, incontinence, impotence, thyroid disorders, skin ailments, broken bones, heart disease, as well as to facilitate childbirth and even as an aphrodisiac.[17]

Use of rare and endangered species

Animal products are used in certain Chinese preparations, which may disturb conservationists, vegans and vegetarians. If informed of such restrictions, practitioners can often use alternative substances.

The practice of using endangered species is controversial within TCM. Modern Materia Medicas such as Bensky, Clavey and Stoger's comprehensive Chinese herbal text discuss substances derived from endangered species in an appendix, emphasizing alternatives.[18]

Poachers hunt restricted animals to supply the black market for such products.[19][20]

The animal rights movement claims that traditional Chinese medicinal solutions still use bear bile (xíong dǎn). In 1988, the Chinese Ministry of Health started controlling bile production, which previously used bears killed before winter. Now bears are fitted with a sort of permanent catheter, which was more profitable than killing the bears.[21] The treatment itself and especially the extraction of the bile is very painful, and damages their stomach and intestines, often resulting in their eventual death. Increased international attention has mostly stopped the use of bile outside of China; gallbladders from butchered cattle (niú dǎn / 牛膽 / 牛胆) are recommended as a substitute for this ingredient.

Medicinal use is impacting seahorse populations.

Traditional Chinese medicine made from plants

There are thousands of herbs that are used as medicines.[31] The following list of herbs represents a very small portion of the pharmacopoeia.

Aconite root

Aconite root is a root commonly used in TCM.[54] It was once so commonly used it was called "the King of the 100 Herbs".[55] Aconite contains the highly toxic neurotoxin aconitine.[56] When a person has a negative reaction to the highly toxic aconite root, some TCM believers think that this is because it was either processed incorrectly or planted on the wrong place or on the wrong day of the year, i.e., for supernatural or astrological reasons, not because of the toxins.Cite error: The <ref> tag has too many names (see the help page).[better source needed]

Camellia

Camellia tea from India, Sri Lanka, Java, Japan is used in TCM for aches and pains, digestion, depression, detoxification, as an energizer and, to prolong life.[57]

Cayenne

Cayanneis believed under TCM to be a prophalactic medicine.[58]

Chinese Cucumber

Chinese cucumber (Trichosanthes kirilowi) is believed to treat tumors, reduce fevers, swelling and coughing, abscesses, amenorrhea, jaundice, and polyuria.

Extracts are extremely toxic. Side effects include hormone changes, allergic reaction, fluid in the lungs or brain, bleeding in the brain, heart damage, seizures, and fever.[59]

Ginger

Ginger root Zingiber officinale) has been used in China for over 2,000 years under a belief that it aids digestion and treats uspet stomach, diarrhea, and nausea. TCM also teaches that it helps treat arthritis, colic, diarrhea, and heart conditions. Traditional Chinese medicine believes that it treats the common cold, flu-like symptoms, headaches, and menstrual cramps. Today, health care professionals commonly recommend to help prevent or treat nausea and vomiting associated with motion sickness, pregnancy, and cancer chemotherapy. It is also used as a digestive aid for mild stomach upset, as support in inflammatory conditions such as arthritis, and may even be used in heart disease or cancer.[60]

Ginseng

Ginseng root is the most widely sold traditional Chinese medicine. The name "ginseng" is used to refer to both American (Panax quinquefolius) and Asian or Korean ginseng (Panax ginseng), which belong to the species Panax and have a similar chemical makeup. Siberian ginseng or Eleuthero (Eleutherococcus senticosus) is another type of plant. Asian ginseng has a light tan, gnarled root that often looks like a human body with stringy shoots for arms and legs. In ancient times, herbalists thought that because of the way ginseng looks it could treat many different kinds of syndromes, from fatigue and stress to asthma and cancer. In traditional Chinese medicine, ginseng was often combined with other herbs and used often to bring longevity, strength, and mental alacrity to its users. Asian ginseng is believed to enhance the immune system in preventing and treating infection and disease. Several clinical studies report that Asian ginseng can improve immune function. Studies have found that ginseng seems to increase the number of immune cells in the blood, and improve the immune system's response to a flu vaccine. In one study, 227 participants received either ginseng or placebo for 12 weeks, with a flu shot administered after 4 weeks. The number of colds and flu were two-thirds lower in the group that took ginseng. [61]

Ginseng contains stimulants, but may produce side effect including high blood pressure, low blood pressure, and mastalgia.[62] Ginseng may also lead to induction of mania in depressed patients who mix it with antidepressants.[63] One of the most common and characteristic symptoms of acute overdose of ginseng from the genus Panax is bleeding. Symptoms of mild overdose with Panax ginseng may include dry mouth and lips, excitation, fidgeting, irritability, tremor, palpitations, blurred vision, headache, insomnia, increased body temperature, increased blood pressure, edema, decreased appetite, increased sexual desire, dizziness, itching, eczema, early morning diarrhea, bleeding, and fatigue.[51] Symptoms of gross overdose with Panax ginseng may include nausea, vomiting, irritability, restlessness, urinary and bowel incontinence, fever, increased blood pressure, increased respiration, decreased sensitivity and reaction to light, decreased heart rate, cyanotic facial complexion, red face, seizures, convulsions, and delirium.[31]

Goji berry

Marketing literature for goji berry (wolfberry) products including several "goji juices" suggest that wolfberry polysaccharides have extensive biological effects and health benefits, although none of these claims have been supported by peer-reviewed research.

A May 2008 clinical study published by the peer-reviewed Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine indicated that parametric data, including body weight, did not show significant differences between subjects receiving Lycium barbarum berry juice and subjects receiving the placebo; the study concluded that subjective measures of health were improved and suggested further research in humans was necessary.[64] This study, however, was subject to a variety of criticisms concerning its experimental design and interpretations.[65]

Published studies have also reported possible medicinal benefits of Lycium barbarum, especially due to its antioxidant properties,[66] including potential benefits against cardiovascular and inflammatory diseases,[67][68] vision-related diseases[69] (such as age-related macular degeneration and glaucoma[70]), having neuroprotective properties[71] or as an anticancer[72] and immunomodulatory agent.[73]

Wolfberry leaves may be used to make tea,[74] together with Lycium root bark (called dìgǔpí; 地 骨 皮 in Chinese), for traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). A glucopyranoside isolated from wolfberry root bark have inhibitory activity in vitro against human pathogenic bacteria and fungi.[75][76]

Horny goat weed

Horny goat weed (Epimedium spp., Yin Yang Huo, 淫羊藿) is believed to be an aphrodisiac.[77] Exploitation of wild populations is having potentially serious consequences for the long-term survival of several species.[78]

Strychnine tree seeds

Strychnine tree seeds (Strychnos nux-vomica, Ma Quan Zi) are marketed and sold with a claim to treat diseases of the respiratory tract, anemia, and geriatric complaints; it contains strychnine so can also be used as a poison for rodents.[79]

Willow Bark

Salix genus plants were used since the time of Hippocrates (400 BC) when patients were advised to chew on the bark to reduce fever and inflammation. Willow bark has been used throughout the centuries in China and Europe to the present for the treatment of pain (particularly low back pain and osteoarthritis), headache, and inflammatory conditions such as bursitis and tendinitis. The bark of white willow contains salicin, which is a chemical similar to aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid). It is thought to be responsible for the pain-relieving and anti-inflammatory effects of the herb. In the 1829, salicin was used to develop aspirin. White willow appears to be slower than aspirin to bring pain relief, but its effects may last longer. [80]

Traditional Chinese medicine made from minerals

Sulfide of mercury

Despite its toxicity, sulfide of mercury (cinnabar) has historically been used in traditional Chinese medicine, where it is called zhūshā (朱砂), and was highly valued in Chinese Alchemy. It was also referred to as dān (丹), meaning all of Chinese alchemy, cinnabar, and the "elixir of immortality". Cinnabar (HgS, sulfide of mercury) has been used in Traditional Chinese medicine as a sedative for more than 2000 years, and has been shown to have sedative and toxic effects in mice.[5]

Asbestos

Asbestos ore (Actinolite) is used to treat impotence.[6]

Lead oxide

Lead elixir (Lead oxide, Qian Dan) is believed to aid in expelling parasites, is toxic to humans, and is marketed and sold worldwide.[81]

Pills and powders

The TCM industry traditionally supplied medicines as powders to be measured and/or compounded by individual practitioners. More recently, soluble granules and tablets have become available with specific dosage levels. Modern formulations in pills and sachets used 675 plant and fungi ingredients and about 25 from non-plant sources such as snakes, geckos, toads, frogs, bees, and earthworms.[citation needed]

Acupuncture, moxibustion, and auriculotherapy

Acupuncture is an alternative medicine that treats patients by insertion and manipulation of needles in the body. Its proponents variously claim that it relieves pain, treats infertility, treats disease, prevents disease, promotes general health, or can be used for therapeutic purposes.[82] Acupuncture typically incorporates traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) as an integral part of its practice and theory. The term “acupuncture” is sometimes used to refer to insertion of needles at points other than traditional ones, or to applying an electric current to needles in acupuncture points.[83][84] Acupuncture dates back to prehistoric times, with written records from the second century BCE. Different variations of acupuncture are practiced and taught throughout the world.

Acupuncture is often accompanied by moxibustion, which involves burning mugwort on or near the skin at an acupuncture point. [85] There are three methods of moxibustion: Direct scarring, direct non-scarring, and indirect moxibustion. Direct scarring moxibustion places a small cone of mugwort on the skin at an acupuncture point and burns it until the skin blisters, which then scars after it heals. [85] Direct non-scarring moxibustion removes the burning mugwort before the skin burns enough to scar, unless the burning mugwort is left on the skin too long. [85] Indirect moxibustion holds a cigar made of mugwort near the acupuncture point to heat the skin, or holds it on an acupuncture needle inserted in the skin to heat the needle.[85] The Chinese character for acupuncture means "acupuncture-moxibustion".

Auriculotherapy (耳灼疗法/耳燭療法) applies acupuncture or moxibustion to the ear. It is believed that a part of the ear (the auricle) is a microsystem with the entire body represented on it.

The effectiveness of acupuncture beyond the placebo effect of a nonpenetrating sham treatment placebo effect is not well established.[86] A systematic review found that acupuncture is no more effective than a nonpenetrating sham treatment for treating post operative nausea.[87][88] A 2008 meta analysis pooled studies without placebos with those that had them concluded that combining acupuncture with conventional infertility treatments such as IVF improves the success rates of such medical interventions, but did not conclude that acupuncture was more effective than a sham treatment.[89] There is conflicting evidence that it can treat chronic low back pain,[90][91] and moderate evidence of efficacy for neck pain[92][93] and headache.[94] For most other conditions[95] reviewers have found either a lack of efficacy (e.g., help in quitting smoking[96]) or have concluded that there is insufficient evidence to determine if acupuncture is effective (e.g., treating shoulder pain[97]). While little is known about the mechanisms by which acupuncture may act, a review publishe in an alternative medicine journal of neuroimaging research suggests that specific acupuncture points have distinct effects on cerebral activity in specific areas that are not otherwise predictable anatomically.[98] The website Quackwatch mentions that TCM has been the subject of criticism as having unproven efficacy and an unsound scientific basis.[99]

The evidence for acupuncture's effectiveness for anything but the relief of some types of pain and nausea has not been established.[100][101][102] Systematic reviews have concluded that acupuncture is no more effective than nonpenetrating stimulation of one point to reduce some types of nausea.[87] Evidence for the treatment of other conditions is equivocal.[86] Although evidence exists for a very small and short-lived effect on some types of pain, several review articles discussing the effectiveness of acupuncture have concluded it is possible to explain as a placebo effect.[100][103] Publication bias is a significant concern when evaluating the literature. Reports from the US National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine In America (NCCAM), the American Medical Association (AMA) and various US government reports have studied and commented on the efficacy of acupuncture. There is general agreement that acupuncture is safe when administered by well-trained practitioners using sterile needles.[24][104][105] The World Health Organization (WHO) has compiled a list of disorders for which acupuncture might have an effect; adverse reactions to chemotherapy and radiation, induction of labor, sciatica, dysmenorrhea, depression, hypertension, rheumatoid arthritis, and low back pain.[106]

Cupping

Cupping (拔罐) is a type of Chinese massage, cupping consists of placing several glass "cups" (open spheres) on the body. A match is lit and placed inside the cup and then removed before placing the cup against the skin. As the air in the cup is heated, it expands, and after placing in the skin, cools, creating lower pressure inside the cup that allows the cup to stick to the skin via suction. When combined with massage oil, the cups can be slid around the back, offering "reverse-pressure massage".===

Die-da or Tieh Ta

Die-da or Tieh Ta (跌打) is usually practiced by martial artists who know aspects of Chinese medicine that apply to the treatment of trauma and injuries such as bone fractures, sprains, and bruises. Some of these specialists may also use or recommend other disciplines of Chinese medical therapies (or Western medicine in modern times) if serious injury is involved. Such practice of bone-setting (整骨) is not common in the West.

Gua Sha

Gua Sha (“to lift up for cholera”, or “to scrape for cholera”) is abrading the skin until red spots then bruising cover the area to which it is done. It is believed that this treatment is for almost any ailment including cholera. The red spots and bruising take 3 to 10 days to heal. It is believed that most people can tolerate the pain of treatment, but there is often some soreness in the area that has been treated.[107][108] Gua Sha: A Clinical Overview, Arya Nielson, Chinese Medicine Times, [22]</ref>[109]

Physical Qigong exercises

Physical Qigong exercises such as Tai chi chuan (Taijiquan 太极拳/太極拳), Standing Meditation (站樁功), Yoga, Brocade BaDuanJin exercises (八段锦/八段錦) and other Chinese martial arts.

Breathing and meditation exercise

Qigong (气功/氣功) and related breathing and meditation exercise.

Massage

Tui na (推拿) massage: a form of massage akin to acupressure (from which shiatsu evolved). Oriental massage is typically administered with the patient fully clothed, without the application of grease or oils. Choreography often involves thumb presses, rubbing, percussion, and stretches.

Fengshui aesthetics and Chinese astrology

TCM doctors may also incorporate beliefs about the astrological alignment of buildings (Fengshui aesthetics, 风水/風水) or astrological beliefs about the year, month, date, and hour of birth (Bazi, 八字).[1][3][4][2]

Diagnostics

Tongue and pulse diagnosis and acupuncture treatment

Examination of the tongue and the pulse are among the principal diagnostic methods in traditional Chinese medicine. The surface of the tongue is believed to contain a map of the entire body, and is used to determine acupuncture points to manipulate. For example, teeth marks on one part of the tongue might indicate a problem with the heart, while teeth marks on another part of the tongue might indicate a problem with the liver.[110] The pulse-reading component of the touching examination is so important that Chinese patients may refer to going to the doctor as "Going to have my pulse felt."[111]

There are four types of TCM diagnostic methods: observe (望 wàng), hear and smell (闻/聞 wén), ask about background (问/問 wèn) and touching (切 qiè).[112] Acupuncture practitioners believe it can be used to treat infertility, and “both pregnancy and the sex of a child can be diagnosed from the pulses by a skilled practitioner”, as part of an overall reproductive technology.[113]

Theoretical superstructure

Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) is based on Yinyangism (which was later absorbed by Daoism).[114] From this follows the belief that all parts of the universe (including the human body) are interconnected by correspondence.[115][23] For example, the number of meridians has at times been seen in correspondence with the number of rivers flowing through the ancient Chinese empire, and the number of acupuncture points has been seen in correspondence with the number of days in a year.[22][1][2]

Theoretical basis of model of the body

This article appears to contradict the article TCM model of the body. |

As a first step of systematization, certain body functions are identified as being connected and ascribed to a common functional entity (e.g., nourishing the tissues and maintaining their moisture is seen as connected and the functional entity identified to be in charge is: xuě/blood).

The most important functional entities stipulated are qì, xuě (‘’blood‘’), the five zàng organs, the six fǔ organs, and the meridians.[116]

Beliefs about qi

TCM distinguishes several different kinds of qi (气).[117]. In a general sense, qi is something that is defined by five "cardinal functions":[118][119]

- Actuation (推动, tuīdòng) - of all physical processes in the body, especially the circulation of all body fluids such as blood in their vessels. This includes actuation of the functions of the zàng-fú organs and meridians.

- Warming (温煦, wēnxù) - the body, especially the limbs.

- Defense (防御, fángyù) - against Exogenous Pathogenic Factors

- Containment (固摄, gùshè) - of body fluids, i.e. keeping blood, sweat, urine, semen etc. from leakage or excessive emission.

- Transformation (气化, qìhuà) - of food, drink, and breath into qi, xuě, and jīnyė (‘’fluids‘’, see below), and/or transformation of all of the latter into each other.

Qi is believed to be partially generated from food and drink, and partially from air (by breathing).[citation needed] Another considerable part of it is inherited from the parents and will be consumed in the course of life.[120]

In terms of location, TCM uses special terms for qi running inside of the blood vessels and for qi which is distributed in the skin, muscles, and tissues between those. The former is called yíng-qì (营气), its function is to complement xuě and its nature has a strong yin aspect (although qi in general is considered to be yang). The latter is called weì-qì (卫气), its main function is defence and it has pronounced yang nature.[121]

Qi also circulates in the meridians. Just as the qi held by each of the zàng-fú organs, this is considered to be part of the ‘’principal‘’ qi (元气, pinyin: yuán qì) of the body (also called 真气 pinyin: zhēn qì, ‘’true‘’ qi, or 原气 pinyin: yuán qì, ‘’original‘’ qi).[122]

Xue (Blood)

In contrast to most of the other functional entities, blood (xuě 血 is visible, and has believed funcions pertaining to the mind.[123].

Xuě is defined by its functions of nourishing all parts and tissues of the body and safeguarding an adequate degree of moisture[124], and of sustaining and soothing both consciousness and sleep[125]. TCM practitioners believe that pale complexion, dry skin and hair, dry stools, numbness of hands and feet, forgetfulness, insomnia, excessive dreaming, and anxiety are symptoms of a dysfunction of xuě, such as a lack of it.[126][127]

Jinye

Closely related to xuě are the jīnyė (津液, usually translated as ‘’body fluids‘’), and just like xuě they are considered to be yin in nature, and defined first and foremost by the functions of nurturing and moisturizing the different structures of the body[128]. Their other functions are to harmonize yin and yang, and to help with secretion of waste products[129].

Jīnyė are ultimately extracted from food and drink, and constitute the raw material for the production of xuě; conversely, xuě can also be transformed into jīnyė.[130] Their palpable manifestations are all bodily fluids: tears, sputum, saliva, gastric juice, joint fluid, sweat, urine, etc.[131]

Zang-fu

The zàng-fǔ (simplified Chinese: 脏腑; traditional Chinese: 臟腑) constitute the centre piece of TCM's systematization of bodily functions. Bearing the names of organs, they are, however, only secondarily tied to (rudimental) anatomical assumptions (the fǔ a little more, the zàng much less)[132]. As they are primarily defined by their functions (please see below), they are not equivalent to the anatomical organs - to highlight this fact, their names are usually capitalized.

The term zàng (脏) refers to the five entities considered to be yin in nature - Heart, Liver, Spleen, Lung, Kidney -, while fǔ (腑) refers to the six yang organs - Small Intestine, Large Intestine, Gallbladder, Urinary Bladder, Stomach and Sānjiaō.[133]

The zàng's essential functions consist in production and storage of qì and blood; in a wider sense they are stipulated to regulate digestion, breathing, water metabolism, the musculoskeletal system, the skin, the sense organs, aging, emotional processes, mental activity etc.[134] The fǔ organs' main purpose is merely to transmit and digest (传化, pinyin: chuán-huà)[135] substances like waste, food, etc.

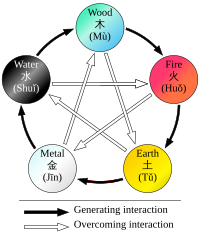

Since their concept was developed on the basis of Wǔ Xíng philosophy, each zàng is paired with a fǔ, and each zàng-fǔ pair is assigned to one of five elemental qualities (i.e., the Five Elements or Five Phases).[136] These correspondences are stipulated as:

- Fire (火) = Heart (心) and Small Intestine (小肠) (and, secondarily, Sānjiaō [三焦, ‘’Triple Burner‘’] and Pericardium [心包])

- Earth (土) = Spleen (脾) and Stomach (胃)

- Metal (金) = Lung (肺) and Large Intestine (大肠)

- Water (水) = Kidney (肾) and Bladder (膀胱)

- Wood (木) = Liver (肝) and Gallbladder (胆)

The zàng-fǔ are also connected to the twelve standard meridians - each yang meridian is attached to a fǔ organ and five of the yin meridians are attached to a zàng. As there are only five zàng but six yin meridians, the sixth is assigned to the Pericardium, a peculiar entity almost similar to the Heart zàng.[137]

Theoretical basis of meridians

The meridians (经络, pinyin: jīng-luò) are believed to be channels running from the zàng-fǔ in the interior (里, pinyin: lǐ) of the body to the limbs and joints ("the surface" [表, pinyin: biaǒ]), transporting qi and xuĕ (blood).[138][139]. TCM identifies 12 "regular" and 8 "extraordinary" meridians[140]; the Chinese terms being 十二经脉 (pinyin: shí-èr jīngmài, lit. "the Twelve Vessels") and 奇经八脉 (pinyin: qí jīng bā mài) respectively[141]. There's also a number of less customary channels branching off from the "regular" meridians.[142]

History

The practice of acupuncture probably dates back to the stone age, as suggested by findings of ancient stone needles [143]. Also, hieroglyphs and pictographs documenting acupuncture and moxibustion have been found which are dating back to the Shang Dynasty (1600-1100 BC)[144].

When acupuncture (and herbal medicine) became integrated into an embracing medical theory system is difficult to judge. TCM theory is, however, inextricably intertwined with the principles of Yinyangism[145] (i.e., the combination of Wǔ Xíng theory with Yin-yang theory)[146], which was represented for the first time by Zōu Yǎn (340 - 260 BC))[147].

The earliest and most fundamental composition identified in TCM is the Huăngdì Neìjīng[148] (黄帝内经, Yellow Emperor's Inner Canon), probably dating back to the second century BC[149]. According to legend, it was composed by the mythical Yellow Emperor (said to have lived 2697 - 2597 BC)[150] as a result of a dialogue with his ministers[151]. It states that to be a master physician, one must master the use of metaphors as they apply to medicine and the body.[152]

Mythical origin was also claimed regarding the Shénnóng Běn Cǎo Jīng (神农本草经, Shennong's Materia Medica) - it traditionally was attributed to the legendary emperor Shénnóng (神农, lit. "Divine Farmer"), said to have lived around 2800 BC.[153] The original text has been lost, however, there are extant translations[154]. The true date of origin is believed to fall into the late Western Han dynasty[155] (i.e., the first century BC).

TCM's second central classical composition, the Shāng Hàn Zábìng Lùn (伤寒杂病论, later divided into Shāng Hàn Lùn and Jīnguì Yàolüè), was written by Zhang Zhongjing (张仲景) during the Han Dynasty, approximately around 200 AD.

Subsequent centuries saw a large number of prominent doctors developing medical theories on the basis of the classical works, or contributing original material which would later be brought in tune with the TCM system:[156]

| Han Dynasty (206 BC–AD 220) to Three Kingdoms Period (220 - 280 AD) |

|

| Jin Dynasty (265 - 420) |

|

| Tang Dynasty (618 - 907) |

|

| Song Dynasty (960 – 1279): |

|

| Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368) |

|

| Ming Dynasty (1368–1644, considered the golden age of acupuncture and moxibustion, spawning many famous doctors and books) |

|

| Qing Dynasty (1644–1912): |

|

See also

- Alternative medicine

- American Journal of Chinese Medicine (journal)

- Ayurveda

- Chinese classic herbal formula

- Chinese food therapy

- Chinese herbology

- Chinese patent medicine

- List of branches of alternative medicine

- List of topics characterized as pseudoscience

- Medicinal mushrooms

- Pharmacognosy

- Public health in the People's Republic of China

- Traditional Korean medicine

- Traditional Mongolian medicine

- Traditional Tibetan medicine

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Cite error: The named reference

Matuk2006was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c d e f g Acupuncture, American Cancer Society, [1] Cite error: The named reference "AACS" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c Felix Mann, quoted in Bauer, M (2006). "The Final Days of Traditional Beliefs? - Part One". Chinese Medicine Times. 1 (4): 31.

- ^ a b c d e f g Cite error: The named reference

TorTwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b "Neurotoxicological effects of cinnabar (a Chinese mineral medicine, HgS) in mice", Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology, Volume 224, Issue 2, 15 October 2007, Chun-Fa Huanga, Shing-Hwa Liua and Shoei-Yn Lin-Shiau, Pages 192-201, [2]

- ^ a b Encyclopedic Reference of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Xinrong Yang, p.8, [3]

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

CTCMMPwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Barret, S (2007-12-30). "Be Wary of Acupuncture, Qigong, and "Chinese Medicine"". Quackwatch. Retrieved 2010-11-03.

- ^ "Final Report, Report into Traditional Chinese Medicine" (pdf). Parliament of New South Wales. 2005-11-09. Retrieved 2010-11-03.

- ^ a b Harding, Andrew (2006-09-23). "Beijing's penis emporium". BBC News. Retrieved 2009-12-07.

- ^ a b Brown, P. Black Market. MediaStorm, LLC online

- ^ a b 2008 report from TRAFFIC

- ^ a b Facts about traditional Chinese medicine (TCM): rhinoceros horn, Encucolpedia Britanica, [4]

- ^ a b "Rhino horn: All myth, no medicine", National Geographic, Rhishja Larson

- ^ a b "Shark Fin Soup: An Eco-Catastrophe?". Sfgate.com. 2003-01-20. Retrieved 2009-12-07.

- ^ a b Chen1, Tien-Hsi; Chang2, Hsien-Cheh; Lue, Kuang-Yang (2009). "Unregulated Trade in Turtle Shells for Chinese Traditional Medicine in East and Southeast Asia: The Case of Taiwan". Chelonian Conservation and Biology. 8 (1): 11–18. doi:10.2744/CCB-0747.1.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "NOVA Online | Kingdom of the Seahorse | Amanda Vincent". Pbs.org. Retrieved 2009-12-07.

- ^ a b Bensky, Clavey and Stoger (2004). Chinese Herbal Medicine Material Medica (3rd Edition). Eastland Press.

- ^ a b Brian K. Weirum, Special to the Chronicle (2007-11-11). "Will traditional Chinese medicine mean the end of the wild tiger?". Sfgate.com. Retrieved 2009-12-07.

- ^ a b "Rhino rescue plan decimates Asian antelopes". Newscientist.com. Retrieved 2009-12-07.

- ^ a b "治人病还是救熊命——对养熊“引流熊胆”的思考"南风窗. November 12, 2002

- ^ a b c "There are 365 days in the year, while humans have 365 joints [or acupoints]... There are 12 channel rivers across the land, while humans have 12 channel", A Study of Daoist Acupuncture & Moxibustion, Cheng-Tsai Liu, Liu Zheng-Cai, Ka Hua, p.40, [5]

- ^ a b The ABCs of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Acupuncture.com

- ^ a b c NIH Consensus Development Program (November 3–5, 1997). "Acupuncture --Consensus Development Conference Statement". National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 2007-07-17.

- ^ Some acupuncture points which treat disorders of blood, Journal of Chinese Medicine, Peter Deadman and Mazin Al-Khafaji, [6]

- ^ Ahn, AC; Colbert, AP; Anderson, BJ; Martinsen, OG; Hammerschlag, R; Cina, S; Wayne, PM; Langevin, HM (2008). "Electrical properties of acupuncture points and meridians: a systematic review". Bioelectromagnetics. 29 (4): 245–56. doi:10.1002/bem.20403. PMID 18240287.

- ^ (Scheid , 2002)

- ^ a b c d e Snake Oil, Western Journal of Medicine, Aug 1989;151(2):208, R. A. Kunin

- ^ a b c d Fats that Heal: Fats that Kill, Udo Erasmus, 1993, ISBN 0-920470-38-6

- ^ a b c Lethal Ingestion of Chinese Herbal Tea Containing Ch'an Su, Western Journal of Medicine, 1996 January; 164(1, pp. 71–75, R J Ko, M S Greenwald, S M Loscutoff, A M Au, B R Appel, R A Kreutzer, W F Haddon, T Y Jackson, F O Boo, and G Presicek Cite error: The named reference "LICHT" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c Chinese Medical Herbology and Pharmacology, by John K. Chen, Tina T. Chen

- ^ "Towards a Safer Choice - The Practice of Traditional Chinese medicine In Australia - Summary of Findings". Health.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 2009-12-07.

- ^ A Promising Anticancer and Antimalarial Component from the Leaves of Bidens pilosa. Planta Med. 2009;75:59-61

- ^ Synthesis and biological evaluation of febrifugine analogues as potential antimalarial agents. BIOORGANIC & MEDICINAL CHEMISTRY. 2009;17 13: 4496-502

- ^ U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, [7]

- ^ "MHRA finds contaminated Chinese, Ayurvedic medicines". Nutraingredients.com. Retrieved 2009-12-07.

- ^ American Cancer Society. Chinese Herbal Medicine. http://www.cancer.org/docroot/ETO/content/ETO_5_3x_Chinese_Herbal_Medicine.asp

- ^ "香港容易混淆中藥". Hkcccm.com. Retrieved 2009-12-07.

- ^ "¡u¨~µv¡v»P¡u¤úµv¡v¤Å²V²c¨Ï¥Î". .news.gov.hk. 2004-05-03. Retrieved 2009-12-07.

- ^ "Chinese medicine Natrii Sulfas not to be confused with chemical Sodium Nitrite". Info.gov.hk. 2004-05-03. Retrieved 2009-12-07.

- ^ "âÏõͼÆ×-¿óÎïÀà(¿óÎïÀà)". 100md.com. Retrieved 2009-12-07.

- ^ Foster & Yue 1992, p.11

- ^ Foster & Yue 1992, p. 11

- ^ a b c Chinese Herbal Medicine: Formulas & Strategies, Volker Scheid, Dan Bensky, Andrew Ellis, Randall Barolet

- ^ a b c d Chinese Herbal Medicine: Materia Medica, Dan Bensky, Steven Clavey, Erich Stoger, Andrew Gamble, Lilian Lai Bensky

- ^ a b c An Illustrated Chinese Materia Medica, Jing-Nuan Wu

- ^ a b c A Materia Medica for Chinese Medicine: plants, minerals and animal products, Carl-Herman Hempen

- ^ Ziheche, TCM Treatment, [8]

- ^ a b c The Traditional Chinese Medicine Materia Medica Clinical Reference, Peter Holmes (Author), Jing Wang (Author), Heather McIver

- ^ Herbal Database, Wu Ling Zhi, [9]

- ^ a b Chinese Medical Herbology and Pharmacology, John Chen and Tina Chen, Art of Medicine Press, ISBN 0-97406-35-0-9, [10]

- ^ Flying Squirrel – Associated Typhus, Infectious Diseases, 2003, Mary G. Reynolds, John W. Krebs, James A. Comer, John W. Sumner, Thomas C. Rushton, Carlos E. Lopez, William L. Nicholson, Jane A. Rooney, Susan E. Lance-Parker, Jennifer H. McQuiston, Christopher D. Paddock, James E. Childs

- ^ Herbal Database, Wu Ling Zhi, [11]

- ^ "Aconitum in Traditional Chinese, Medicine—A valuable drug or an unpredictable risk?", Journal of Ethnopharmacology, Volume 126, Issue 1, 29 October 2009, Judith Singhuber, Ming Zhu, Sonja Prinz, Brigitte Kopp, Pages 18-30

- ^ "The importance of aconite (fuzi)" http://www.classicalchinesemedicine.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/04/fruehauf_fuziinterview1.pdf

- ^ Chan TY (2009). "Aconite poisoning". Clinical Toxicology (Philadelphia, Pa.). 47 (4): 279–85. doi:10.1080/15563650902904407. PMID 19514874.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "The distribution of minerals and flavonoids in the tea plant (Camellia sinensis)", Il Farmaco, Volume 56, Issues 5-7, 1 July 2001, Lydia Ferrara, Domenico Montesanoa, and Alfonso Senatore, Pages 397-401

- ^ http://www.umm.edu/altmed/articles/cayenne--000230.htm]

- ^ Chinese Cucumber, Drugs.com, [12]

- ^ Ginger, University of Maryland Medical Center, [13]

- ^ [14]

- ^ http://www.aafp.org/afp/20031015/1539.html

- ^ Fugh-Berman, Adriane (2000). "Herb-drug interactions". The Lancet. 355 (9198): 134–138. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(99)06457-0.

- ^ Amagase H, Nance DM (2008). "A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, clinical study of the general effects of a standardized Lycium barbarum (Goji) Juice, GoChi". J Altern Complement Med. 14 (4): 403–12. doi:10.1089/acm.2008.0004. PMID 18447631.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Daniells S. (2008). "Questions raised over Goji science". NutraIngredients.com-USA.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Wu SJ, Ng LT, Lin CC (2004). "Antioxidant activities of some common ingredients of traditional chinese medicine, Angelica sinensis, Lycium barbarum and Poria cocos". Phytother Res. 18 (12): 1008–12. doi:10.1002/ptr.1617. PMID 15742346.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jia YX, Dong JW, Wu XX, Ma TM, Shi AY (1998). "[The effect of lycium barbarum polysaccharide on vascular tension in two-kidney, one clip model of hypertension]". Sheng Li Xue Bao (in Chinese). 50 (3): 309–14. PMID 11324572.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Luo Q, Li Z, Huang X, Yan J, Zhang S, Cai YZ (2006). "Lycium barbarum polysaccharides: Protective effects against heat-induced damage of rat testes and H2O2-induced DNA damage in mouse testicular cells and beneficial effect on sexual behavior and reproductive function of hemicastrated rats". Life Sci. 79 (7): 613–21. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2006.02.012. PMID 16563441.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cheng CY, Chung WY, Szeto YT, Benzie IF (2005). "Fasting plasma zeaxanthin response to Fructus barbarum L. (wolfberry; Kei Tze) in a food-based human supplementation trial". Br. J. Nutr. 93 (1): 123–30. doi:10.1079/BJN20041284. PMID 15705234.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Chan HC, Chang RC, Koon-Ching Ip A; et al. (2007). "Neuroprotective effects of Lycium barbarum Lynn on protecting retinal ganglion cells in an ocular hypertension model of glaucoma". Exp. Neurol. 203 (1): 269–73. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.05.031. PMID 17045262.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Yu MS, Leung SK, Lai SW; et al. (2005). "Neuroprotective effects of anti-aging oriental medicine Lycium barbarum against beta-amyloid peptide neurotoxicity". Exp. Gerontol. 40 (8–9): 716–27. doi:10.1016/j.exger.2005.06.010. PMID 16139464.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gan L, Hua Zhang S, Liang Yang X, Bi Xu H (2004). "Immunomodulation and antitumor activity by a polysaccharide-protein complex from Lycium barbarum". Int. Immunopharmacol. 4 (4): 563–9. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2004.01.023. PMID 15099534.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ He YL, Ying Y, Xu YL, Su JF, Luo H, Wang HF (2005). "[Effects of Lycium barbarum polysaccharide on tumor microenvironment T-lymphocyte subsets and dendritic cells in H22-bearing mice]". Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Xue Bao (in Chinese). 3 (5): 374–7. doi:10.3736/jcim20050511. PMID 16159572.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Made-in-China.com, Wolfberry (Goji) Tea

- ^ Lee DG, Park Y, Kim MR; et al. (2004). "Anti-fungal effects of phenolic amides isolated from the root bark of Lycium chinense". Biotechnol. Lett. 26 (14): 1125–30. doi:10.1023/B:BILE.0000035483.85790.f7. PMID 15266117.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lee DG, Jung HJ, Woo ER (2005). "Antimicrobial property of (+)-lyoniresinol-3alpha-O-beta-D-glucopyranoside isolated from the root bark of Lycium chinense Miller against human pathogenic microorganisms". Arch. Pharm. Res. 28 (9): 1031–6. doi:10.1007/BF02977397. PMID 16212233.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Horny Goat Weed, Altmedicine.com

- ^ Epimedium, ChemEurope.com

- ^ Ma Qian Zi, Chinese Medical Tools, Acupuncture.com

- ^ [15]

- ^ Qian Dan (Lead Oxide), TCM Herbs, Sacred Lotus Arts Traditional Chinese Medicine, [16]

- ^ Novak, Patricia D.; Dorland, Norman W.; Dorland, William Alexander Newman (1995). Dorland's Pocket Medical Dictionary (25th ed.). Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders. ISBN 0-7216-5738-9. OCLC 33123537.

- ^ de las Peñas, César Fernández; Arendt-Nielsen, Lars; Gerwin, Robert D (2010). Tension-type and cervicogenic headache: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. Jones & Bartlett Learning. ISBN 9780763752835.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Robertson, Valma J; Robertson, Val; Low, John; Ward, Alex; Reed, Ann (2006). Electrotherapy explained: principles and practice. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 9780750688437.

- ^ a b c d Moxibustion, Acupuncture Today, [17]

- ^ a b Ernst E; Pittler MH; Wider B; Boddy K (2007). "Acupuncture: its evidence-base is changing". Am. J. Chin. Med. 35 (1): 21–5. doi:10.1142/S0192415X07004588. PMID 17265547.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help) - ^ a b Lee A; Done ML; Lee, Anna (2004). "Stimulation of the wrist acupuncture point P6 for preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (3): CD003281. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003281.pub2. PMID 15266478.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help) - ^ Dibble SL; Luce J; Cooper BA; Israel J; Cohen M; Nussey B; Rugo H (2007). "Acupressure for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: a randomized clinical trial". Oncol Nurs Forum. 34 (4): 813–20. doi:10.1188/07.ONF.xxx-xxx. PMID 17723973.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help) - ^ Manheimer E; Zhang G; Udoff L; Haramati A; Langenberg P; Berman BM; Bouter LM (2008). "Effects of acupuncture on rates of pregnancy and live birth among women undergoing in vitro fertilization: systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ. 336 (7643): 545–9. doi:10.1136/bmj.39471.430451.BE. PMID 18258932.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help) - ^ Furlan AD; van Tulder MW; Cherkin DC; et al. (2005). "Acupuncture and dry-needling for low back pain". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (1): CD001351. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001351.pub2. PMID 15674876.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help) - ^ Manheimer E; White A; Berman B; Forys K; Ernst E (2005). "Meta-analysis: acupuncture for low back pain" (PDF). Ann. Intern. Med. 142 (8): 651–63. PMID 15838072.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help) - ^ Trinh K; Graham N; Gross A; Goldsmith C; Wang E; Cameron I; Kay T (2007). "Acupuncture for neck disorders". Spine. 32 (2): 236–43. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000252100.61002.d4. PMID 17224820.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help) - ^ Trinh KV; Graham N; Gross AR; et al. (2006). "Acupuncture for neck disorders". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 3 (3): CD004870. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004870.pub3. PMID 16856065.

{{cite journal}}:|first8=has generic name (help); Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help) - ^ "The Cochrane Collaboration - Acupuncture for idiopathic headache. Melchart D, Linde K, Berman B, White A, Vickers A, Allais G, Brinkhaus B". Cochrane.org. Retrieved 2009-12-07.

- ^ Cochrane Collaboration. [Search all Cochrane reviews for "acupuncture". Retrieved 30 January 2008.

- ^ "Acupuncture and related interventions for smoking cessation". Cochrane.org. Retrieved 2009-12-07.

- ^ "Acupuncture for shoulder pain". Cochrane.org. 2005-04-20. Retrieved 2009-12-07.

- ^ Lewith GT; White PJ; Pariente J (2005). "Investigating acupuncture using brain imaging techniques: the current state of play". Evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine: eCAM. 2 (3): 315–9. doi:10.1093/ecam/neh110. PMID 16136210. Retrieved 2007-03-06.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Stephen Barrett, M.D. "Be Wary of Acupuncture, Qigong, and "Chinese Medicine"". Retrieved 2010-05-31.

- ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 16420542 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=16420542instead. - ^ Shapiro R (2008). Suckers: How alternative medicine makes fools of us all. Vintage Books. OCLC 267166615.

- ^ Singh & Ernst, 2008, Chapter 2, pg. 39-90.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1136/bmj.a3115 , please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1136/bmj.a3115instead. - ^ "Acupuncture". US National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2006. Retrieved 2006-03-02.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 12801494 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=12801494instead. - ^ "World Health Organization: Acupuncture: Review and Analysis of Reports on Controlled clinical Trials: 3. Diseases and disorders that can be treated with acupuncture". who.int. 2003. Retrieved 2011-03-03.

- ^ Gua Sha, Guasha.com, Arya Nielsen, Fellow - National Academy of Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine, former Chair of the New York State Board for Acupuncture, [18]

- ^ GuaSha Treatment of Disease, TCMWell.com

- ^ The effect of Gua Sha treatment on the microcirculation of surface tissue: a pilot study in healthy subjects, A Nielsen, N Knoblauch, GJ Dobos, [19]

- ^ “Tongue Diagnosis in Chinese Medicine”, Giovanni Maciocia, Eastland Press; Revised edition (June 1995)

- ^ Kaptchuk 2000

- ^ Maciocia, Giovanni (1989). The Foundations of Chinese Medicine. Churchill Livingstone.

- ^ ” Chinese Medicine and Assisted Reproductive Technology for the Modern Couple”, Roger C. Hirsh, OMD, L.Ac., Acupuncture.com, [20]

- ^ Liu 1999, p. 38

- ^ Liu 1999, p. 39-41

- ^ Aung, S.K.H. & Chen, W.P.D. (2007): Clinical introduction to medical acupuncture. Thieme Mecial Publishers. ISBN 1-58890-221-8, p. 19

- ^ Aung, S.K.H. & Chen, W.P.D. (2007): Clinical introduction to medical acupuncture. Thieme Mecial Publishers. ISBN 1-58890-221-8, pp 11-12

- ^ 郭卜乐 (24t October 2009). "气" (in Chinese). Retrieved 2 December 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Aung, S.K.H. & Chen, W.P.D. (2007): Clinical introduction to medical acupuncture. Thieme Mecial Publishers. ISBN 1-58890-221-8, pp 11-12

- ^ "What is Qi? Qi in TCM Acupuncture Theory". 20 June 2006. Retrieved 3 December 2010.

- ^ Elizabeth Reninger. "Qi (Chi): Various Forms Used In Qigong & Chinese Medicine - How Are The Major Forms Of Qi Created Within The Body?". Retrieved 6 December 2010.

- ^ 郭卜乐 (24t October 2009). "气" (in Chinese). Retrieved 6 December 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "Blood from a TCM Perspective". Shen-Nong Limited. Retrieved 7 December 2010.

- ^ "The Concept of Blood (Xue) in TCM Acupuncture Theory". 24 June 2006. Retrieved 3 December 2010.

- ^ "Blood from a TCM Perspective". Shen-Nong Limited. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

- ^ "The Concept of Blood (Xue) in TCM Acupuncture Theory". 24 June 2006. Retrieved 3 December 2010.

- ^ "Blood from a TCM Perspective". Shen-Nong Limited. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

- ^ "Body Fluids (Yin Ye)". copyright 2001-2010 by Sacred Lotus Arts. Retrieved 9 December 2010.

- ^ "三、津液的功能 ...(三)调节阴阳 ...(四)排泄废物 ..." [3.) Functions of the Jinye: ... 3.3.)Harmonizing yin and yang ... 3.4.)Secretion of waste products ...] As seen at: "《中医基础理论》第四章 精、气、血、津液. 第四节 津液" (in Chinese). Retrieved 9 December 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "Body Fluids (Yin Ye)". copyright 2001-2010 by Sacred Lotus Arts. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

- ^ "津液包括各脏腑组织的正常体液和正常的分泌物,胃液、肠液、唾液、关节液等。习惯上也包括代谢产物中的尿、汗、泪等。" [The (term) jinye comprises all physiological bodily fluids of the zang-fu and tissues, and physiological secretions, gastric juice, intestinal juice, saliva, joint fluid etc. Costumarily this also includes metabolic products like urine, sweat, and tears, etc.] As seen at: "《中医基础理论》第四章 精、气、血、津液. 第四节 津液" (in Chinese). Retrieved 9 December 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "Cultural China - Chinese Medicine - Basic Zang Fu Theory". Retrieved 8 January 2011.

- ^ by citation from the Huangdi Neijing's Suwen: ‘’言人身脏腑中阴阳,则脏者为阴,腑者为阳。‘’[Within the human body's zang-fu, there's yin and yang; the zang are yin, the fu are yang]. As seen at: "略论脏腑表里关系" (in Chinese). 22 January 2010. Retrieved 13 December 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "Cultural China - Chinese Medicine - Basic Zang Fu Theory". Retrieved 26 February 2011.

- ^ "中医基础理论-脏腑学说" (in Chinese). 11 June 2010. Retrieved 14 December 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Aung, S.K.H. & Chen, W.P.D. (2007): Clinical introduction to medical acupuncture. Thieme Mecial Publishers. ISBN 1-58890-221-8, pp 15-16<

- ^ Aung, S.K.H. & Chen, W.P.D. (2007): Clinical introduction to medical acupuncture. Thieme Mecial Publishers. ISBN 1-58890-221-8, p. 16

- ^ "中医基础理论辅导:经络概念及经络学说的形成: 经络学说的形成" (in Chinese). Retrieved 13 January 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Aung, S.K.H. & Chen, W.P.D. (2007): Clinical introduction to medical acupuncture. Thieme Mecial Publishers. ISBN 1-58890-221-8, p. 20

- ^ Aung, S.K.H. & Chen, W.P.D. (2007): Clinical introduction to medical acupuncture. Thieme Mecial Publishers. ISBN 1-58890-221-8, p. 19

- ^ "经络学" (in Chinese). Retrieved 22 February 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Aung, S.K.H. & Chen, W.P.D. (2007): Clinical introduction to medical acupuncture. Thieme Mecial Publishers. ISBN 1-58890-221-8, p. 19

- ^ Chiu, M (1993). Chinese acupuncture and moxibustion. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 2. ISBN 0443042233

- ^ Robson, T (2004). An Introduction to Complementary Medicine. Allen & Unwin. pp. 90. ISBN 1741140544

- ^ see Huang neijing Suwen, chapter 3.

- ^ "Zou Yan". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 01 March 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Zou Yan". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 01 March 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "The Medical Classic of the Yellow Emperor". cultural-china.com. Retrieved 24 February 2011.

- ^ Lu, Gwei-djen and Joseph Needham (1980). Celestial Lancets: A History and Rationale of Acupuncture and Moxa. New York, NY: Routledge/Curzon. pp. 89-90.ISBN 0-7007-1458-8

- ^ "Yellow Emperor." The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. 2008. Encyclopedia.com

- ^ "The Medical Classic of the Yellow Emperor". cultural-china.com. Retrieved 24 February 2011.

- ^ "Overview of Traditional Chinese Medicine: The Cooking Pot Analogy", Veterinary Herbal Medicine , 2007, Steven Paul Marsden, Pages 51-58, [21]

- ^ "Shennong 神农". cultural-china.com. Retrieved 24 February 2011.

- ^ Du Halde J-B (1736): Description géographique, historique etc. de la Chine, Paris

- ^ "Shennong 神农". cultural-china.com. Retrieved 24 February 2011.

- ^ An excerpt of this book is translated in http://www.pacificcollege.edu/alumni/newsletters/winter2004/damp_warmth.html.

- ^ Charles Benn, China's Golden Age: Everyday Life in the Tang Dynasty. Oxford University Press, 2002, ISBN 0-19-517665-0), pp. 235.

- ^

- Wu Jing-nuan. (2005). An Illustrated Chinese Materia Medica, p. 5.

References

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (February 2010) |

- Aung, S.K.H. & Chen, W.P.D. (2007): Clinical introduction to medical acupuncture. Thieme Mecial Publishers. ISBN 1-58890-221-8

- Benowitz, Neal L. (2000) Review of adverse reaction reports involving ephedrine-containing herbal products. “Submitted to U.S. Food and Drug Administration. January 17.

- Chan, T.Y. (2002). Incidence of herb-induced aconitine poisoning in Hong Kong: impact of publicity measures to promote awareness among the herbalists and the public. Drug Saf. 25:823–828.

- Chang, Stephen T. The Great Tao; Tao Longevity; ISBN 0-942196-01-5 Stephen T. Chang

- Hongyi, L., Hua, T., Jiming, H., Lianxin, C., Nai, L., Weiya, X., Wentao, M. (2003) Perivascular Space: Possible anatomical substrate for the meridian. Journal of Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 9:6 (2003) pp851–859

- Jin, Guanyuan, Xiang, Jia-Jia and Jin, Lei: Clinical Reflexology of Acupuncture and Moxibustion; Beijing Science and Technology Press, Beijing, 2004. ISBN 7-5304-2862-4

- Kaptchuck, Ted J., The Web That Has No Weaver; Congdon & Weed; ISBN 0-8092-2933-1Z

- Maciocia, Giovanni, The Foundations of Chinese Medicine: A Comprehensive Text for Acupuncturists and Herbalists; Churchill Livingstone; ISBN 0-443-03980-1

- Matuk, C. (2006) "Seeing the Body: The Divergence of Ancient Chinese and Western Medical Illustration", JBC Vol. 32, No. 1 2006, retrieved 2011-02-20

- Ni, Mao-Shing, The Yellow Emperor's Classic of Medicine: A New Translation of the Neijing Suwen with Commentary; Shambhala, 1995; ISBN 1-57062-080-6

- Holland, Alex Voices of Qi: An Introductory Guide to Traditional Chinese Medicine; North Atlantic Books, 2000; ISBN 1-55643-326-3

- Needham, Joseph (2002). Celestial Lancets. ISBN 9780700714582.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)* Unschuld, Paul U., Medicine in China: A History of Ideas; University of California Press, 1985; ISBN 0-520-05023-1 - Porkert, Manfred (1974). The Theoretical Foundations of Chinese Medicine. MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-16058-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Qu, Jiecheng, When Chinese Medicine Meets Western Medicine - History and Ideas (in Chinese); Joint Publishing (H.K.), 2004; ISBN 962-04-2336-4

- Scheid, Volker, Chinese Medicine in Contemporary China: Plurality and Synthesis; Duke University Press, 2002; ISBN 0-8223-2857-7

- Unschuld, Paul U. (1985). Medicine in China: A History of Ideas. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-05023-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

- Sivin, Nathan, ed. (2000). Medicine. (Science and civilisation in China, Vol. VI, Biology and Biological Technology, Part 6). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 10-ISBN 0-521-63262-5; 13-ISBN 978-0-521-63262-1; OCLC 163502797