Tokmak

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2023) |

Tokmak

Токмак | |

|---|---|

Historical merchant's building in Tokmak | |

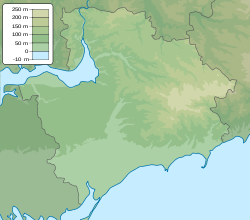

Interactive map of Tokmak | |

| Coordinates: 47°15′20″N 35°42′20″E / 47.25556°N 35.70556°E | |

| Country | |

| Oblast | Zaporizhzhia Oblast |

| Raion | Polohy Raion |

| Hromada | Tokmak urban hromada |

| Founded | 1784 |

| Area | |

| • Land | 32.46 km2 (12.53 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 43 m (141 ft) |

| Population (2022) | |

• Total | 29,573 |

| Demonym(s) | Tokmachanin, Tokmachanka, Tokmachany |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Postal code | 71700 |

| Area code | +380 6178 |

| Licence plate | AP, KR / 08 |

| Climate | Dfa |

| Website | http://tokmakcity.org.ua |

Tokmak (Ukrainian: Токмак, IPA: [tokˈmɑk]) is a small city in Polohy Raion, Zaporizhzhia Oblast, in south-central Ukraine. It stands on the Tokmak River, a tributary of the Molochna. It is the administrative centre of the Tokmak urban hromada, and was the centre of the Tokmak Raion until that was disestablished in 2020. Its population is approximately 29,573 (2022 estimate).[1]

Tokmak has been occupied by Russia since early March 2022.[2]

Etymology

[edit]The name of the town comes from the Tokmak River. One common theory is that the hydronym comes from the Turkish tokmak ("mallet, stick, hammer"). An alternative theory is that the name comes from the Turkish dökmek ("to pour"). Another possibility is that the name comes from a tribe belonging to the Cumans or the Kyrgyz people.[3]

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]The territories around Tokmak have been inhabited since the Neolithic era. This is evidenced by the excavations of settlements and burial mounds near the town, where burials dating from the Bronze Age were found. There have also been excavations indicating the presence of the Sarmatians (3rd-2nd centuries BC), the Scythians (4th century BC), and of older Neolithic nomads (10th-12th centuries BC).[citation needed]

From the archival documents of the Zaporizhian Sich (mid-18th century), it is known that there were seasonal deployments of the Cossack Kurins along the Tokmak River where they engaged in fishing and hunting. They were adjacent to the seasonal sheep-breeding camps of the Crimean Tatars and the Armenians, and the nomad camps of the Nogais, which sometimes led to conflicts and legal complaints from both sides.[citation needed]

Founding

[edit]The official year of the foundation of Tokmak is 1784, which coincides with the conquest of Crimea by the Russian Empire and the formation of the Taurida Oblast. Intensive settlement of the region began after the end of the Russo-Turkish War (1787–1792), when several families descended from Zaporozhian Cossacks and state serfs from the area of Poltava settled on the banks of the Tokmak River. The village was named Velykyi Tokmak, or Bolshoi Tokmak (both "Great Tokmak").[citation needed] Its rapid growth was facilitated by the existence of a trade route known as the "Old Chumatsky Road" that passed through the area.

Russian Empire

[edit]In 1796, Tokmak was appointed the center of the Melitopolsky Uyezd (Melitopol District) of the Taurida Oblast. In 1797, the Melitopol Uyezd was included in the Mariupol uezd of the Novorossiya Governorate, the center of which again became Tokmak. In 1801, the center of the Uyezd was moved to Orikhiv, and Tokmak remained the center of the Velykyi Tokmak Volost. Sloboda of Novoalexandrovka, which became the town of Melitopol in 1842, was also part of the Bolshoi Tokmak Volost in 1814–1829.[4]

In the summer of 1842, a strong fire broke out in the city of Orikhiv, and the administrative offices were again transferred to Velykyi Tokmak. In the same year, the Berdyansky Uyezd was created and both Tokmak (which became a provincial town) and Orikhiv were included with the new Uyezd.

During the Crimean War, Velykyi Tokmak temporarily became the center of the Berdyansky Uyezd. Between 1854 and 1856, a military hospital was located in the village. 281 soldiers who died of wounds and diseases were buried in Tokmak.[5]

In 1861, the settlement was granted the status of a small town and became part of the Berdyan district of the Tavrya province. The inhabitants were engaged in agriculture, cattle breeding, trade, and artisanry. The goods were sold during the spring (9 May) and autumn (1 October) fairs, which included merchants from places such as Moscow, Kursk, and Berdyansk.

By the beginning of the 20th century, there were about one thousand workers at nine Tokmak enterprises. The largest of them were factories for the production of agricultural machinery. These factories were founded in 1882 by I. I. Fuchs and in 1885 by I. V. Kleiner.

Further economic development was facilitated by the construction of a railway line connecting the town with the Pryshyb Station on the Kharkiv–Sevastopol line. On the eve of the First World War, local manufacturers and merchants built the railway line between Tsarekostyantynivka (Komysh-Zoria) and Fedorivka station (Novobohdanivka), and the Velikiy Tokmak station on it, which further contributed to the growth of trade and the development of the city.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Tokmak was one of the largest settlements in Northern Tavria. A branch of the Azov-Don Commercial Bank contributed to the development of the local economy. The company "Triumph" began to produce gasoline engines. Berger and Zagorelin, machine-building and iron-foundry factories, began operations around this time as well. Despite this modest industrialization, the majority of the population was still working the land. At that time, there was a small printing house, two photographic studios, a hospital with 15 beds, and 5 elementary schools in Tokmak.

Soviet era

[edit]In 1917, the publication of the local newspaper "News of the Bolshoi Tokmak Council of Workers', Soldiers' and Peasants' Deputies" began.[6] In 1918, the Soviets established control of the town.

From 23 March 1921 to 1 December 1922, the town of Velykyi Tokmak served as the administrative center of the Veliky Tokmak Povit. The resolution of the All-Ukrainian Committee of 7 March 1923, created the Velykyi Tokmak Raion with its administrative center in the town of Velykyi Tokmak.[7] In those years, the military commissar in Tokmak was Sydir Kovpak.

In addition to the formation of administrative authorities, attention was paid in particular to industry and education. A library was opened on the premises of the party committee and the executive committee of the council. The executive committee also organized classes in order to eliminate illiteracy. Professionals of various types were educated at mechanical technical school, a nursing school, and a collective farming administration school. There were 8 clubs, 2 cinemas, and 13 general education schools. An infectious disease department and 2 pharmacies also began operating.

From 1923 to 1927, the factory "Red Progress" produced a serial three-wheeled tractor known as the "Zaporozhets".[8] For the original design and its high productivity, the factory staff were awarded a state diploma of the 1st degree. "Red Progress" was the first state factory of agricultural machinery. In the 1930s, the plant produced 75% of the low-power diesel engines in the USSR. Oleksandr Ivchenko began his work in here in the "Red Progress" factory.

On 7 October 1941, during the German invasion of the USSR, Soviet troops retreated from Tokmak. [9][10]

During the Nazi occupation of 1941-1943, two partisan units operated in the area: A Soviet partisan unit led by V.G. Akulov and I.K. Shchava. And an underground partisan group organized by G.F. Burkut, V.V. Veretennikov and V. O. Fedyushin. On 20 September 1943, the city was liberated during the Donbass operation by the Soviet troops of the Southern Front (Soviet Union): the 2nd Guards Army, the 4th Guards Motor Rifle Division, and the 4th Guards Cavalry Corps.[10]

On 30 December 1962, Velikiy Tokmak was renamed Tokmak and received the status of a city of regional significance.[11]

Independent Ukraine

[edit]On 5 September 2002, the city of Tokmak was divided into 8 microdistricts: "Korolenko", "Kalininsky", "Livy Bereh" (English: "Left Bank"), "Ryzhok", "Zaliznychny", "Akhramiivka", "Kovalsky", "Tsentralʹny" (English: "Central").

On 19 May 2016, the Zaporizhia Regional State Administration issued Order No. 275 which renamed five streets in the city of Tokmak:

- Shchorsa Street became Zaliznychna Street. (Zaliznychna meaning railroad.)

- Volodarsky Street became Vasyl Vyshyvanyi Street.

- Zhovtneva Street became Heroes of Ukraine Street.

- Proletarska Street became Victory Street.

- Revolution Street became Central Street. [12]

On 12 June 2020, in accordance with the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine's Order No. 713-R, "On the determination of administrative centers and approval of the territories of territorial communities of Zaporizhzhya Oblast", the city acquired the status of administrative center of the Tokmak urban hromada.[citation needed] On 17 July 2020, Tokmak Raion was dissolved and Tokmak became part of Polohy Raion.[13]

Russo-Ukrainian War

[edit]During the southern campaign of the Russian invasion phase of the Russo-Ukrainian War, a Russian armored brigade broke into Tokmak on 26 February 2022 despite the resistance of Ukrainian defenders. During the night of 27 February and the early morning of 28 February, Russian forces attacked the city in earnest.[14] An infiltrated Russian sabotage and reconnaissance group that had previously stolen Ukrainian military uniforms from a Ukrainian military depot attacked.[15] According to a report from the Zaporizhzhia State Administration, as a result of the confrontation, the enemy lost a large number of personnel and retreated to the southern outskirts of the city.[16]

On 2 March 2022, the Ministry of Defense of the Russian Federation announced that the city had been captured by Russian troops.[2] Deputy Mayor Volodymyr Kharlov disputed this claim, although he reported that the situation in the city was extremely difficult the city was surrounded. The deputy mayor also claimed that there were military casualties on both sides along with civilian casualties during a battle which saw the use of tanks, artillery, and other weapons. He added that the city authorities were not cooperating with the Russian forces nor contacting them.[17] However, by 4 March, Mayor Ihor Kotelevskyi announced that the city authorities were working on the restoration of power to the city and that an agreement had been made with the Russian armed forces to establish humanitarian corridors.[18] By 7 March, Tokmak was fully captured by Russian forces.[19] An unknown number of citizens reportedly held rallies against the occupation of the Russian military throughout the rest of March.[20][21]

On 3 April 2022, it was reported that the Russian military intended to hold a "referendum" in the city of Tokmak. The leaders of the Zaporizhia Oblast appealed to citizens with a message that the referendum would not be legal.[22]

On 21 April 2022, Russian singer Yulia Chicherina took part in the lighting of the eternal flame near the Tokmak memorial to the fallen participants of the Second World War.[23]

On 7 May 2022, news broke of the death of Mayor Igor Kotelevskyi. The cause of Kotelevsky's death is unknown, but "Ukrinform" noted at the time that, according to the unofficial version, he allegedly committed suicide. Kotelevsky had been first elected Mayor of Tokmak in August 2009.[24][25][26]

Near the end of June, 2022, there were reports of Russian soldiers dismantling the Tokmak solar power plant and relocating it to Russia. These reports were later disproven.[27]

On 11 July 2022, Ukrainian forces struck a Russian military base in Tokmak. After several hits in the area of the military unit and warehouses, an ammunition storage site was destroyed.[28]

Starting in early 2023, extensive fortifications were built by the Russian military in a ring around Tokmak.[29] The Russian Ministry of Defense had anticipated that the main thrust of the 2023 Ukrainian counteroffensive will be in the direction of the city, and three consecutive defensive belts were built.[30] This prediction turned out to be correct, and the fortifications succeeded in their goal as the counteroffensive failed to penetrate the line and fell short of reaching Tokmak, with small scale Russian offensive operations eventually restarting in February 2024 in and around Robotyne, just north of the first defensive belt.[31]

Governance

[edit]The city of Tokmak is divided into 8 microdistricts:

- "Korolenko"

- "Kalininsky"

- "Livy Bereh" (English: "Left Bank")

- "Ryzhok"

- "Zaliznychny"

- "Akhramiivka"

- "Kovalsky"

- "Tsentralʹny" (English: "Central")

There are 12 village councils operating in the territory of the Tokmak urban hromada.

Demographics

[edit]| Year | Pop. |

|---|---|

| 1952 | 28,575 |

| 1979 | 42,178 |

| 1989 | 45,112 |

| 2001 | 36,275 |

| 2021 | 30,125 |

The city of Tokmak had a population of 30,125 in 2021. The most recent information regarding native language and ethnicity usage comes from the 2001 Ukrainian Census. At that point in time, 70.25% of the population of Tokmak spoke Ukrainian, and 29.35% spoke Russian. Ethnically, 81.4% of the population was Ukrainian; 16.6% Russian; 0.5% Belarusian; and 1.5% other.[32] The exact ethnic composition was as follows:[33]

Education

[edit]The city has an educational institution where you can get a higher education: Tokmak Mechanical College of Zaporozhye National Technical University. There is also the Tokmak educational and consulting center of the National University of Shipbuilding. There are also 10 schools and 8 kindergartens. City secondary school No. 2 is named after a Hero of the Soviet Union Alexei N. Kot.

Culture

[edit]In Tokmak, there is a city cultural center, a city museum of local history, a public folk museum of OJSC "Pivddieselmash" (Diesal Plant), three public libraries, and children's music and art schools.

There are 21 groups of amateur artists and 6 clubs with more than 300 participants in the city's House of Culture.

The decorative and applied art works of embroiderers V. M. Melai and Z. P. Fedan and the basket weaving of V. D. Olyzko were demonstrated at exhibitions in the cities of Zaporizhzhia and Kyiv.

There are 17,307 exhibits in the city museum of local history, and 8,485 exhibits in the state museum. The city has 47 historical and artistic monuments.

There is a local radio station and three local newspapers which cover the events of the city and the surrounding region.

Economy

[edit]Tokmak Solar Energy is large solar power plant with a 50 MW capacity.

Largest enterprises in Tokmak:

- Open joint-stock company: "Pivdendizelmash" (Diesel Plant). Formerly known as "Red Progress". Red Progress Ukrainian wiki page.

- CJSC: "Tokmak-Agro"

- Public joint-stock company: "Tokmak Forging and Stamping Plant" (TKSHZ).

- Tokmak factory of building materials "Stroykeramika".

- CJSC: "Tokmak Plant "Progress""

- LLC: "Tokmack Ferroalloy Company" LLC

- LLC: Tokmak Solar Energy

Infrastructure

[edit]The Velikiy Tokmak railway station of the Zaporizhzhia Directorate (part of the regional branch: Cisdnieper Railways) operates in the city on the line: Fedorivka - Verkhniy Tokmak II - Volnovakha.

Notable people

[edit]- Petro Yefymenko (1835–1907), historian and ethnographer.

- Grigory Chechet (1870–1922), one of the earliest Ukrainian aircraft designers.

- Marko Bezruchko (1883–1944), Ukrainian military commander and a General of the Ukrainian National Republic.

- Sydir Kovpak (1887–1967), a leader of Soviet partisans in Ukraine during World War II. In 1921, he was the military commissar in Tokmak.

- Ivan Kovtunenko (1896–1921), a Cossack of the 4th Kyiv Division of the UNR Army, Hero of the Second Winter Campaign.

- Vasily Denisenko (1896–1964), historian and ethnographer.

- Oleksandr Ivchenko (1903–1968), a Soviet design engineer of aircraft engines.

- Lew Grade (1906–1998), Ukrainian-British media proprietor who was born in Tokmak.

- Bernard Delfont (1909–1994), Ukrainian-British theatre impresario who was born in Tokmak.

- Pavlo Matyukh (1911–1980), Hero of the Soviet Union who fought in World War II.

- Alexei Kot (1914–1997), World War II pilot, Hero of the Soviet Union, and author.

- Hryhoriy Sardak (1916–2001), Ukrainian surgeon and a pioneer of vascular surgery.

- Grigory Okhay (1916–2002), a Soviet MiG-15 flying ace during the Korean War.

- Georgy Krasulya (1929–1996), Opera singer and Honored Artist of the Ukrainian SSR (1974).

- Anatoly Lagetko (1936–2006), a Soviet boxer who was born in Tokmak.

- Yakiv Ochkalenko (1951–2021), Soviet and Ukrainian football coach and official.

- Serhiy Ivanov (born 1952), a Ukrainian politician and Governor of Sevastopol who was born in Tokmak.

- Sergey and Nikolai Radchenko (born 1958), Twin brothers who formed a musical duo known as Radchenko Brothers.

- Oleksandr Zayets (1962–2007), Soviet professional footballer who was born in Tokmak.

- Yuri Ganus (born 1964), General Director of the Russian anti-doping agency RUSADA.

- Kostyantyn Havryk (1978–2019), a sergeant in the Armed Forces of Ukraine, a participant in the Russo-Ukrainian War.

- Andriy Oberemko (born 1984), Ukrainian professional footballer.

- Pavlo Levchuk (1988–2014), a Ukrainian political scientist, teacher, participant in the Russo-Ukrainian War.

- Oleksandr Shelepaev (1991–2014), a sergeant in the Armed Forces of Ukraine, a participant in the Russo-Ukrainian War.

- Maksym Shumak (1991–2016), a soldier of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, a participant in the Russo-Ukrainian War.

- Margaryta Yakovenko (born 1992), Spanish language journalist and novelist born in Tokmak.

- Yevhen Pidlepenets (born 1998), Ukrainian professional footballer.

Gallery

[edit]-

Ruins of a mill in Tokmak

-

Diesel machine monument on the plant memorial

-

The plant memorial

-

A market street in Tokmak

-

St. Sergius of Radonezh church

-

Former bank building

-

Ascension Church

-

Tokmak bus station

-

Shevchenko Residential Building of Merchant Blokhinov

-

Fraternal Grave of the Soldiers

References

[edit]- ^ Чисельність наявного населення України на 1 січня 2022 [Number of Present Population of Ukraine, as of January 1, 2022] (PDF) (in Ukrainian and English). Kyiv: State Statistics Service of Ukraine. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 July 2022.

- ^ a b "Украинская армия без боя сдала населенные пункты Токмак и Васильевка". 2 March 2022.

- ^ Evgeny, Pospelov (2002), Geographical names of the world: Toponymic dictionary, Рус. словари, ISBN 5-17-001389-2

- ^ Krylov, N. Очерки по истории города Мелитополя 1814-1917 (in Russian).

- ^ Saenko, V. M. (2008). Токмаччина пiд час Схiдної (Кримської) вiйни (in Ukrainian). Tokmak, Ukraine: Gutenberg Press.

- ^ Catalog: Newspapers of pre-revolutionary Russia 1703-1917.

- ^ "КОРОТКА ІСТОРИЧНА ДОВІДКА ПРО ЗМІНИ АДМІНІСТРАТИВНО-ТЕРИТОРІАЛЬНОГО ПОДІЛУ НА ЗАПОРІЖЖІ (1770-1994 рр.) на 10 сторінках" [BRIEF HISTORICAL INFORMATION ABOUT CHANGES IN THE ADMINISTRATIVE-TERRITORIAL DIVISION IN ZAPORIZHA (1770-1994) in 10 pages.] (in Ukrainian). Archived from the original on 21 June 2016. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- ^ Удод И. С. Токмак — родина отечественного тракторостроения // Мелитопольский краеведческий журнал, 2013, № 1, с. 87-92.

- ^ Медведський В. І., Медведська Г. В. «Что нас ожидает, неизвестно…» // Мелітопольський краєзнавчий журнал, 2020, № 15, с. 75-85

- ^ a b Dudarenko, M. L. (1985). Liberation of cities: a guide to the liberation of cities during the Great Patriotic War of 1941-1945 (in Russian). p. 598.

- ^ "Токмак, Токмацький район, Запорізька область". Історія міст і сіл Української РСР (in Ukrainian).

- ^ "Розпорядження голови Запорізької обласної державної адміністрації від 19.05.2016 року № 275 Перейменування об'єктів топоніміки міст та районів Запорізької області" (PDF). zoda.gov.ua.

- ^ Resolution of the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine, dated 17 July 2020 No. 807-IX: "On the Formation and Liquidation of Districts".

- ^ "У місті Токмаку (Запорізька область) вночі були потужні бої" [In the city of Tokmak (Zaporizhia region) there were heavy battles at night] (in Ukrainian). 28 February 2022.

- ^ "У Токмаку йшли бої з окупантами у військовій формі ЗСУ" [In Tokmak, there were battles with the occupiers who were wearing ZSU military uniforms] (in Ukrainian). 28 February 2022.

- ^ Karateeva, Anastasiya (28 February 2022). "В Токмаке войска оккупантов понесли большие потери" [In Tokmak, the occupying troops suffered heavy losses] (in Russian). Archived from the original on 28 February 2022. Retrieved 11 March 2022.

- ^ "Токмак тримається, але ситуація складна, – заступник мера". 2 March 2022.

- ^ Стало відомо, яка ситуація сьогодні у Токмаку, який перебуває в оточенні російських окупантів. Archived from the original on 12 April 2022. Retrieved on 12 April 2022.

- ^ "Ukraine after 11th night of war: Mayor killed, towns taken, Moscow promises civilian corridors to Russia". Baltic News Network. 7 March 2022. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- ^ В Токмаке люди вышли прогонять русских военных из города (ВИДЕО)

- ^ Герої серед нас: Хто і як відстоює український Токмак. Archived from the original on 29 March 2022. Retrieved on 12 April 2022.

- ^ «Прийшли звірі, можуть зробити, що завгодно». Викрадення та «референдуми» на Запоріжжі. Archived from the original on 21 April 2022. Retrieved on 21 April 2022.

- ^ Одіозна російська пропагандистка Чичеріна приїхала до окупованого Токмака, – ФОТО, ВІДЕО Archived from [1news.zp.ua/odioznaya-rossijskaya-propagandistka-chicherina-priehala-v-okkupirovannyj-tokmak-foto-video/ the original] on 23 April 2022. Retrieved on 30 April 2022.

- ^ Умер мэр оккупированного Токмака — Игорь Котелевский

- ^ Помер мер окупованого Токмака Ігор Котелевський

- ^ Mayer, Patrick (9 July 2023). "Putins letzte Bastion? Ukrainische Kleinstadt wird zu russischer Festung" [Putin's last bastion? Ukrainian town becomes Russian fortress]. Frankfurter Rundschau (in German). Retrieved 18 August 2023.

- ^ "Співвласник сонячної електростанції біля Токмака спростував її вивіз окупантами: що відбувається насправді — Delo.ua". delo.ua (in Ukrainian). 2022-06-24. Retrieved 2023-07-22.

- ^ Украинские военные нанесли удар по вражеской военной базе в Токмаке (фото, видео).

- ^ Palumbo, Daniele; Rivault, Erwan (23 May 2023). "Ukraine war: Satellite images reveal Russian defences before major assault". BBC News. Retrieved 18 September 2023.

- ^ Kilner, James (17 September 2023). "Russia braces for Ukrainian attack on 'linchpin' town". The Telegraph. Retrieved 18 September 2023.

- ^ "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, 24 February 2024". Institute for the Study of War.

- ^ M. Dnistryanskyi . Ethnopolitical geography of Ukraine: problems of theory, methodology, practice. — Lviv: LNU named after Ivan Franko, 2006. — 490 p.

- ^ "Національний склад міст".