Melitopol

This article's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Wikipedia. (April 2022) |

Melitopol

Melitopil | |

|---|---|

From top to bottom and left to right: | |

| Coordinates: 46°50′56″N 35°22′03″E / 46.84889°N 35.36750°E | |

| Country | |

| Oblast | Zaporizhzhia Oblast |

| Raion | Melitopol Raion |

| Hromada | Melitopol urban hromada |

| Established | 1784 |

| City rights | 1842 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Vacant |

| Area | |

• Total | 51 km2 (20 sq mi) |

| Population (2022) | |

• Total | 148,851 |

| Postal Index | 72300 |

| Climate | Cfa |

| Website | www |

| |

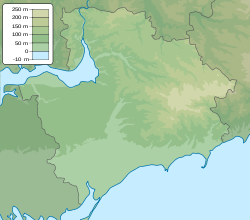

Melitopol[a] is a city and municipality in Zaporizhzhia Oblast, southeastern Ukraine. It is situated on the Molochna River, which flows through the eastern edge of the city into the Molochnyi Lyman estuary. Melitopol is the second-largest city in the oblast after Zaporizhzhia and serves as the administrative centre of Melitopol Raion. As of January 2022, Melitopol's population was estimated to be 148,851.[1]

Melitopol has been under Russian control since March 2022. On September 30, 2022, the city was formally annexed by the Russian Federation; however, it remains internationally recognized as sovereign territory of Ukraine.

The city is located at the crossing of two major European highways: E58 Vienna – Uzhhorod – Kyiv – Rostov-on-Don and E105 Kirkenes – St. Petersburg – Moscow – Kyiv – Yalta. An electrified railway line of international importance goes through Melitopol. The city was once known as "the gateway to the Crimea"; prior to the 2014 Russian annexation of Crimea 80% of passenger trains heading to the peninsula passed through it and during the summer, road traffic reached 45,000 vehicles per day.

Etymology

Native names

Both Ukrainian and Russian names are based on the Greek name Μελιτόπολις, lit. 'honey city'.

- Ukrainian: Мелітополь; IPA: [mel⁽ʲ⁾iˈtɔpolʲ]

- Russian: Мелитополь

Historical names

The city was called Kyz-Yar (Crimean Tatar: Qız Yar; Ukrainian: Киз-Яр), and Novooleksandrivka (Ukrainian: Новоолександрівка) before 1815 and 1842 respectively. It was renamed to the current name after on. In addition, the traditional Ukrainian names Melitopil (Мелітопіль)[2][3] and Melytopil (Мелитопіль)[4] were also used but no longer after the Ukrainian language was oppressed by the Soviet authorities.

History

In July 1769, Russian military commanders built a redoubt there, and Zaporizhia Cossacks carried out their duty service there. On 2 February 1784, Catherine II issued the decree to create the Taurida Oblast on the lands that had been won. The deputy of Novorossiya Grigory Potemkin signed the relation to establish a town that very year – and Cossacks' families and those of retired soldiers of Suvorov settled on the right bank of the Molochna River. Among others, Germans were encouraged to settle in the new province, and some villages in this area were for many years German-speaking, such as Heidelberg (now Pryshyb) some 50 km (31 mi) to the north of Melitopol.[5]

In 1816, the settlement got the name sloboda of Novoalexandrovka. Its population was increasing due to the importation of peasants from the northern provinces of Ukraine and Russia. On 7 January 1842, the sloboda was recognized as a town and received the new name of Melitopol after a port city of Melita (from Greek Μέλι (meli) – "honey") which had been situated on the mouth of the Molochna River. At the end of the 19th century, the "Honey-city"[6] had been developed as a trade center – there were some banks, credit organizations and wholesale stores. The largest enterprises in the city at the time were the iron foundry and the Brothers Klassen's machinery construction factory (1886), the railroad depot and the workshops.

Further development of the city was closely connected with trade, iron and engineering industries, and railway service in the Crimean direction. In the early twentieth century there were fifteen thousand people living in Melitopol. 30 factories and 350 shops operated in the city at that time. In the second half of the twentieth century there was a strong economic growth of the city: new factories, plants, and housing estates were constructed. Sixteen Melitopol business enterprises received All-Soviet Union significance status. Industrial products were exported to more than 50 countries.

World War II

In 1941, the Soviet Union was attacked by Germany. The city became strategically important due to its location. The Red Army was not ready for the war and had to retreat. The German Wehrmacht occupied Melitopol on 6 October 1941. Within one week the entire remaining Jewish population of Melitopol (2,000 men, women and children) were murdered by Einsatzgruppen, which was actively supported by the Wehrmacht. The Germans operated a Nazi prison in the city.[7]

The Wotan Line Battle

After breaking through on the Mius River and defeating Axis troops in the Donbas and Taganrog, the Soviet Southern Front army pursuing the retreating enemy came to the Molochna River on 22 September 1943. Here, in the basin of the Milk River, German troops had begun to build a strong long-term defence which they called the Panther-Wotan line. It was on this line that the fate of the Crimean peninsula and the whole course of offensive operations in the southern Soviet Union were decided.

The German defense consisted of four lines, covered with solid anti-tank ditches and land mines. The first attempt of the Soviet Southern Front army to break through was unsuccessful. Soviet commanders decided to prepare thoroughly a new attempt: the so-called “Melitopol operation”, which was carried out successfully from 26 September to 5 November 1943.

Fighting lasted long, as the Germans introduced fresh reserves in order to keep Melitopol. Finally, after many days of heavy street fighting against vastly superior numbers of men and equipment, German resistance was broken and on 23 October the Red Army took complete control of the city. By decrees of the Presidium of the USSR Supreme Soviet, 87 Red soldiers and airmen were awarded the title of "Hero of the Soviet Union" for their actions in the reconquest of Melitopol.

Russo-Ukrainian War

This section needs to be updated. (February 2024) |

During the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Melitopol was attacked by the Russian forces on 25 February 2022, and captured after heavy fighting by 1 March. Mayor Ivan Fedorov pledged non-cooperation, and locals took to the streets to protest the Russian occupation.[8] On 11 March Fedorov was abducted by the Russian military and released five days later as part of a prisoner swap.[9] In the meantime, the Russian forces had attempted to install former councilor Halyna Danylchenko of the Opposition Bloc party as acting mayor. The Melitopol City Council declared that this was an attempt to "illegally create an occupation administration"[10] and appealed to the Prosecutor General of Ukraine to launch a pre-trial investigation into Danylchenko and her party.[10] On 23 March 2022, now-exiled Mayor Fedorov reported that the city was experiencing problems with food, medication, and fuel supplies, and that the Russian military was seizing businesses, intimidating the local population, and holding several journalists in custody.[9]

On 30 May, a bomb exploded in central Melitopol during a humanitarian aid transfer between local residents and Russian personnel, injuring at least three people, according to the Russian investigative committee's website which referenced "Ukrainian saboteurs" as the possible perpetrators. In a statement from exile, Ivan Fedorov alluded to the possibility that the bombing was connected to local Ukrainian resistance fighters.[11] On 30 September, in a move unrecognized internationally, the city was annexed by Russia as part of the Russian annexation of Zaporizhzhia oblast.

Russian occupation authorities instituted a policy of re-Sovietization of the city, including restoring Soviet names to Melitopol's streets, these names were introduced by the Bolsheviks in the 1920s.[12]

On 27 April 2023, the police chief defector Oleksandr Mishchenko was killed in a bomb blast at his apartment block. His assassin(s) were Ukrainian partisans.[13]

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1897 | 15,489 | — |

| 1926 | 25,249 | +63.0% |

| 1939 | 75,748 | +200.0% |

| 1959 | 94,670 | +25.0% |

| 1970 | 136,860 | +44.6% |

| 1979 | 160,664 | +17.4% |

| 1989 | 173,385 | +7.9% |

| 2001 | 160,657 | −7.3% |

| 2011 | 157,141 | −2.2% |

| 2022 | 148,851 | −5.3% |

| Source: [14] | ||

According to the 1897 census, Jews made up 42% of the total population.[15]

According to the 2001 Ukrainian census, the population of the city was 160,352. Ukrainians made up 55.2% of the city's population, Russians 38.9%, and Bulgarians 1.8%. The exact ethnic composition was as follows:[16]

Geography

Climate

Melitopol has a humid continental climate that borders on a humid subtropical climate (Dfa bordering on Cfa within the Köppen climate classification). The temperature is slightly below freezing in winter and hot in summer. January is the coolest month, having a mean of −1.8 °C (28.8 °F) and an average low of −4.5 °C (23.9 °F). February has a lower average low of −4.7 °C (23.5 °F). July is the warmest month, with a mean of 23.6 °C (74.5 °F) and an average high of 30.0 °C (86.0 °F).

Melitopol receives 488.8 millimetres (19.24 in) of precipitation annually. Precipitation is distributed evenly year-round, with no wet or dry season, although some months are wetter or have more precipitation days than others. June is the wettest month, receiving 57.5 millimetres (2.26 in) of rain on average. October is the driest month, receiving 32.9 millimetres (1.30 in) of rainfall. There are a similar amount of precipitation days each month. August has the least, with 4.3 days. December and January have the most, with 7.5 days. Melitopol has 75.2 precipitation days annually on average. Humidity is higher in winter than in summer. August is the least humid month. December is the most humid.

| Climate data for Melitopol (1981–2010 normals) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 1.3 (34.3) |

2.2 (36.0) |

7.8 (46.0) |

16.1 (61.0) |

22.7 (72.9) |

26.9 (80.4) |

30.0 (86.0) |

29.4 (84.9) |

23.2 (73.8) |

15.7 (60.3) |

7.5 (45.5) |

2.4 (36.3) |

15.4 (59.7) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −1.8 (28.8) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

3.1 (37.6) |

10.4 (50.7) |

16.4 (61.5) |

20.8 (69.4) |

23.6 (74.5) |

22.7 (72.9) |

16.9 (62.4) |

10.4 (50.7) |

3.8 (38.8) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

10.4 (50.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −4.5 (23.9) |

−4.7 (23.5) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

5.6 (42.1) |

10.9 (51.6) |

15.3 (59.5) |

17.7 (63.9) |

16.9 (62.4) |

11.7 (53.1) |

6.3 (43.3) |

0.9 (33.6) |

−3.1 (26.4) |

6.1 (43.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 37.1 (1.46) |

35.8 (1.41) |

35.4 (1.39) |

36.5 (1.44) |

45.5 (1.79) |

57.5 (2.26) |

45.2 (1.78) |

37.9 (1.49) |

37.0 (1.46) |

32.9 (1.30) |

42.0 (1.65) |

46.0 (1.81) |

488.8 (19.24) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 7.5 | 6.8 | 7.0 | 6.3 | 6.9 | 7.1 | 5.4 | 4.3 | 4.8 | 4.7 | 6.9 | 7.5 | 75.2 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 85.7 | 82.6 | 77.7 | 68.4 | 64.5 | 65.3 | 61.0 | 59.8 | 67.5 | 75.9 | 85.3 | 86.9 | 73.4 |

| Source: NCEI[17] | |||||||||||||

Culture

There is a design project of the Intercultural Park, prepared by a group of European architects and designers led by Mark Glaudemans – Director of the European Laboratory for urban planning, the Dean of the Academy of Architecture and Urbanism (city of Tilburg, Netherlands).[18] In Melitopol removed first short film in 2015, "The Zone".

Melitopol has 38 monuments, memorials and statues registered.[19] One of them is the statue of Bohdan Khmelnytsky, the famous hetman of the Zaporozhian Host. His images are printed on Ukrainian 5 hryvnia's banknotes. The other one represents Ostap Bender a hero of the book of Ilf and Petrov The Twelve Chairs.[citation needed]

Melitopol has a number of museums, including the Melitopol Museum of Local History, which holds a collection of 60,000 objects relating to the history, culture and environment of the city.[20] On 10 March 2022, after the Russian attack on the city, the director of the museum, Leila Ibragimova, was arrested at her home by Russian forces, was interrogated in an unknown location and later released.[21] [22]

The Stone Grave

There is the unique relic of the Stone Grave (Ukrainian: Кам'яна могила, translit. Kamyana mohyla, Russian: Каменная могила) 12 km (7 mi) north of Melitopol. It is a relic of sandstone from the Sarmatian epoch of the Tertiary period. Its exact coordinates are 46°56′59.33″N 35°28′11.59″E / 46.9498139°N 35.4698861°E

Melitopol honey

The city actively created its own brand as a "city of honey", which is the translation of the Greek word "melitos". The city formed a cluster of honey producers, prepared investment projects for the establishment of an apitherapy center (treatment with the help of bee products) and encourages the creation of souvenir products made from honey.[citation needed]

Commemorative silver coin

In October 2013, the National Bank of Ukraine introduced a new commemorative silver coin on the 70th anniversary of the Melitopol offensive against German troops and the liberation of the city of Melitopol on 23 October 1943. The new coin was called "The Breakthrough of Soviet Troops Against the German Defence Line Wotan and liberation of Melitopol" and each of the 30,000 limited-edition coins was worth the equivalent of US-$ 5.[23]

-

The entrance to Melitopol

-

Gorky park in Melitopol

Economy

There is a well-developed, internationally important engine-constructing industry. Thanks to the rich historical heritage, economic and geographical situation and enterprising citizens the city has developed mechanical engineering, light and food industry. The city's development is driven by engineering industries, that have received new impulse with the establishment of more than 100 new small and medium engineering business enterprises, united in the cluster "AgroBOOM".

Machine engineering complex of the city is represented by 8 large plants and more than 100 small and medium-sized enterprises formed after 1991. Mechanical engineers of the city mainly produce goods for the agricultural sector.

Enterprises include:

- The plant BIOL makes dishes,

- The PLANT OF INNOVATION TECHNOLOGIES is manufactures high-tech electronic equipment, software, high-frequency generators, equipment for ground handling of airliners (Airbus, Bombardier, Boeng, AN, Il, Tu), frequency converters for railway, urban transport, subway.

- The plant TALCO collaborates with General Motors and Festo.

- The plant AUTOPRIVOD is produces YaMZ engines.

- The only plant in Ukraine that produces engines for cars is AvtoZAZ-MOTOR.

- The plant AVTOTSVETLIT is the only plant in Ukraine that produces five types of complex castings (steel, cast iron, magnesium, and aluminium); it also produces shock absorbers for VAZ.

- The company ROSTA performs the commercialisation of research in agricultural machinery and irrigation systems.

- The plant MzTK is a unique enterprise that produces turbines for mobile equipment.

- The plant TERMOLIT induction furnaces for foundry operations and other products of metal processing.

The following companies can be called the basis of light industry in the city:

- Melitopol Sewing Production Enterprise exports its goods. The factory has "dressed" the Air France and Polaris French railway employees, Dutch police and firefighters, and Italian tax police.

- Melitopol Knitting Factory Nadezhda is a manufacturer of knitwear products.

- Furniture production is well developed; more than 20 small and medium enterprises are working in this field, distributing its products throughout Ukraine.

Thanks to the proximity of the agricultural areas and raw materials of the Zaporizhzhia, Mykolaiv, Kherson, and Dnipropetrovsk regions, the food industry is well represented in the city. The main enterprises of the food industry are:

- Melitopol Meat Processing Plant produces sausages.

- Melitopol Milk Plant and Oil Extraction Plant are enterprises that belong to a major food-holding, Olkom.

- Melitopol grain elevator.

Education

In 1874, a technical school was founded in the city which, after a series of reforms and transformations, became Tavria State Agrotechnological University.

The city now has two public universities − Tavria State Agrotechnological Academy[24] and Bohdan Khmelnytsky Melitopol State Pedagogical University,[25] as well as a private institute – Zaporizhzhia Institute of Economics and Information Technologies.

A long history of universities and schools is one of the reasons that Melitopol is called "the city of students". More than 10% of its citizens are students.

The strong system of education is represented by different types of educational institutions at all levels of accreditation: two universities, four branches of different universities in Ukraine, seven professional schools, and three colleges.

26 pre-schools are operating in the city, in which 6,000 young citizens are being educated. For more than 500 children with special needs under the age of seven years, there are rehabilitation programs to provide the needed services.

Educational services for 14,000 students are provided by 23 secondary schools. There is a center of labor training and professional orientation for young people. A network of six non-school institutions are the following: the Centre of Ecological-Naturalistic Art for Youth, the Center of Tourist and Local Lore Creativity for Youth, the Station of Young Technicians, the Vodvudenko Palace for Children and Teenagers Creativity, Small Academy of Sciences, and the Center of Children and Teenagers. Other creative centers unite nine communal hobby clubs.

Transportation

The aerodrome close to the city, where the 25th Transport Aviation Brigade is based, is not used for passenger services.

The two main highways leading through Melitopol are the M14 Odesa-Novoazovsk Highway and the M26 Kharkiv-Simferopol National Highway.

Melitopol railway station acts as the transit point for passengers travelling between Moscow and the Crimea. The city is called the "gateway to the Crimea".

Melitopol has two bus stations, the older one operates local services, whereas buses from the newer station form part of the national bus service. The marshrutkas, which operate on 34 routes throughout the city, are the main type of public transport used. During the Soviet period, bus companies, including Ikarus, LiAZ, LAZ, and PAZ, ran around 15 routes.

Melitopol's road network is 333 km (207 mi) long. 70% of the city's roads are of inadequate quality.

Twin towns – sister cities

Melitopol is twinned with:

Brive-la-Gaillarde, France

Brive-la-Gaillarde, France Barysaw, Belarus

Barysaw, Belarus Pukhavichy Raion, Belarus

Pukhavichy Raion, Belarus Kėdainiai, Lithuania

Kėdainiai, Lithuania Sliven, Bulgaria

Sliven, Bulgaria

Notable people

- Dmytro Dontsov, who influenced the establishment of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, a right-wing group that strove for Ukrainian independence from the Soviet Union during the 1930s

- Mikhail Lifshitz, Soviet philosopher of art and literary critic

- Pavel Sudoplatov, Soviet intelligence officer

- Grigory Chukhray, Soviet film director and screenwriter

- Yevhen Khacheridi, professional footballer (born 1987)

- Shishi Masaru, sumo wrestler, only Ukrainian in the history of the sport to reach the status of sekitori

Notes

- ^ See the §Etymology section for native and historical names

References

- ^ Чисельність наявного населення України на 1 січня 2022 [Number of Present Population of Ukraine, as of January 1, 2022] (PDF) (in Ukrainian and English). Kyiv: State Statistics Service of Ukraine. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 July 2022.

- ^ Stepan Lvovych Rudnytskyi «Карта України» (transl. 'Map of Ukraine'). — Vienna: Freytag and Berndt, 1918.

- ^ Administrative map of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic in 1927. Territorial division under a three-tier system of governance. Administrative boundaries on March 1, 1927. Scale 1:1,250,000. ‒ M.: Publication of the People's Commissariat of Internal Affairs of the USSR and the State Publishing House of Ukraine [1927].

- ^ Administrative map of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic in 1922: January 1922 r./ People's Commissariat of Internal Affairs Affairs; structure. S. Hurgin. — 1:1 680 000; 40 c. in 1 inch. — Kharkiv. — 1 p.: color., tab. Adm. division, stamp

- ^ "Richard Konkel, genealogist".

- ^ i.e. Melitopol, this is how Melitopol sometimes is referred in the local mass-media

- ^ "Gefängnis Melitopol'". Bundesarchiv.de (in German). Retrieved 26 February 2022.

- ^ "'We are not co-operating': Life in occupied Ukraine". BBC News. 9 March 2022. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ a b "Melitopol mayor accuses Russians of seizing businesses in the city". CNN. 23 March 2022. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ a b "Міськрада Мелітополя називає в.о мера від окупантів державною зрадницею". Українська правда (in Ukrainian). 13 March 2022. Retrieved 13 March 2022.

- ^ "Bomb hits Russian-occupied Ukraine city of Melitopol - Russian, Ukraine officials". Reuters. 30 May 2022. Retrieved 3 June 2022.

- ^ "Оккупационные власти Мелитополя вернули улицам советские названия"

- ^ Greenall, Robert (27 April 2023). "Ukraine war: Partisan attack kills police chief in Russian-occupied Melitopol". BBC.

- ^ "Cities & Towns of Ukraine".

- ^ "Melitopil Jewish Cemetery". European Jewish Cemeteries Initiative. 10 May 2021.

- ^ "Національний склад міст".

- ^ "World Meteorological Organization Climate Normals for 1981–2010". National Centers for Environmental Information. Archived from the original (XLS) on 17 July 2021. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- ^ "Melitopol investment portal". invest-melitopol.org. Archived from the original on 2012-10-30.

- ^ The data from Melitopol's official site – mlt.gov.ua (uk.) Archived 2011-10-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Мелитопольский городской краеведческий музей - MGK Мелитополь". mgk.zp.ua. Retrieved 2022-03-10.

- ^ "In occupied Melitopol, invaders kidnapped a deputy of regional council". Rubryka. 2022-03-10. Archived from the original on 2022-03-10. Retrieved 2022-03-10.

- ^ They put me in a car, put a black bag on my head – Leila Ibrahimova about her detention

- ^ "National Bank of Ukraine issues commemorative coin". Cistran Finance. 21 October 2013. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- ^ Tavria State Agrotechnological Academy Archived 2014-02-09 at the Wayback Machine official site

- ^ Melitopol State Pedagogical University Archived 2022-02-25 at the Wayback Machine official site

External links

Media related to Melitopol at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Melitopol at Wikimedia Commons- Melitopol official website

- Melitopol investment portal

- Melitopol guidebook

- Melitopol – the honey-city: multilingual portal

- Melitopol from Encyclopædia Britannica

- Melitopol map