Timeline of international climate politics

The timeline of international climate politics is a list of events significant to the politics of climate change.

Overview

[edit]The politics of climate change did not reach a prominent place on the world's political agenda until the late 1980s. There had been warnings that climate change could become a civilisation ending threat from as early as the 1930s.[1] Scientists and environmental campaigning groups tried to get policy makers attention with increasing frequency after Charles Keeling's 1960 report of an annual rise in the atmospheric concentration of CO2.[2] Yet until the 1990s, there was little concerted action by the world's policy makers.[note 1][3]

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change was created in 1988 by the World Meteorological Organization and the United Nations Environment Programme. In 1992, the world's governments agreed on the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro. The subsequent landmarks have been the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, the 2009 Copenhagen Summit and the 2015 Paris conference.[3]

Following successful negotiations leading to the 1987 signing of the Montreal Protocol to protect the Ozone layer, politicians and activists were initially relatively optimistic about the prospects for successfully containing the threat of global warming. By the early 2000s, with global emissions having increased significantly since the 1992 agreement, it had become clear that reducing global emissions would be a much more difficult problem.[note 2][3][4]

Timeline

[edit]Events prior to 1980

[edit]

- 1969, on Initiative of US President Richard Nixon, NATO tried to establish a third civil column and planned to establish itself as a hub of research and initiatives in the civil region, especially on environmental topics.[5] Daniel Patrick Moynihan, Nixon's NATO delegate for the topic[5] named acid rain and the greenhouse effect as suitable international challenges to be dealt by NATO. NATO had suitable expertise in the field, experience with international research coordination and a direct access to governments.[5] After an enthusiastic start on authority level, the West German government reacted skeptically.[5] The initiative was seen as an American attempt[5] to regain international terrain after the lost Vietnam War. The topics and the internal coordination and preparation effort however gained momentum in civil conferences and institutions in West Germany and beyond during the Brandt government.[5]

- 1972 United Nations Conference on the Human Environment,[5] leading role of Nobel Prize winning-West German Chancellor Willy Brandt and Swedish Prime Minister Olof Palme,[note 3] West Germany saw enhanced international research cooperation on the greenhouse topic as necessary[5]

- 1977 Sir Crispin Tickell issues his book Climatic Change and World Affairs, instrumental in starting the process of convincing of the U.K. Government.

- 1979: First World Climate Conference[6] in Geneva.

- 1980 Brandt Report issued in New York, concerning the unequal north–south development, the greenhouse effect dealt with in the energy section[7]

1980s

[edit]- 1985: Vienna Convention for the Protection of the Ozone Layer

- 1987: Brundtland Report[7]

- 1987: Montreal Protocol on restricting ozone layer-damaging CFCs demonstrates the possibility of coordinated international action on global environmental issues.

- 1988 James Hansen's congressional testimony on climate change "widely seen as the first high-profile revelation of global heating".[8]

- 1988: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change set up to coordinate scientific research, by two United Nations organizations, the World Meteorological Organization and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) to assess the "risk of human-induced climate change".

1990s

[edit]- 1991 publication of The First Global Revolution by the Club of Rome. A book which argued for a more integrated global approach to climate change to energy production, population growth, water availability, food production, and other environmental issues.

- 1992: United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) was formed to "prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system", based on agreement of the nations that attended the Earth Summit. A central concept was "differentiated responsibility", with developed nations expected to shoulder more of the burden of responding to climate change.

- 1995: First Conference of the Parties of the UNFCCC (COP1) held under the UNFCC in Berlin, Germany. Ends with the non-binding Berlin Mandate agreeing to further negotiations on greenhouse gas reduction.[9]

- 1996, publication of the IPCC Second Assessment Report : Climate Change 1995

- 1996: European Union adopts target of a maximum 2 °C rise in average global temperature

- 25 June 1997: US Senate passes Byrd–Hagel Resolution rejecting Kyoto without more commitments from developing countries[10]

- 1997: Kyoto Protocol agreed at the 3rd Conference of the Parties (COP3). It was the first concrete implementation of the 1992 UNFCCC agreement, and imposed no greenhouse gas emissions reduction targets on developing nations.

2000s

[edit]- 2001: George W. Bush withdraws from the Kyoto negotiations

- 16 February 2005: Kyoto Protocol comes into force (not including the US or Australia)

- 2005: the European Union Emissions Trading Scheme is launched, the first such scheme

- July 2005: 31st G8 summit has climate change on the agenda, but makes relatively little concrete progress

- November/December 2005: United Nations Climate Change Conference; the first meeting of the Parties of the Kyoto Protocol, alongside the 11th Conference of the Parties (COP11), to plan further measures for 2008–2012 and beyond.

- October 2006: The Stern Review is published. It is the first comprehensive contribution to the global warming debate by an economist and its conclusions lead to the promise of urgent action by the UK government to further curb Europe's CO2 emissions and engage other countries to do so. It discusses the consequences of climate change, mitigation measures to prevent it, possible adaptation measures to deal with its consequences, and prospects for international cooperation.

- Publication of the Australian Garnaut review, which like the Stern review also recommended urgent action to mitigate climate change.

- 2008: The Parliament of the United Kingdom passes the Climate Change Act 2008 to transition to a low-carbon economy.

- June 2009: US House of Representatives passes the American Clean Energy and Security Act, the "first time either house of Congress had approved a bill meant to curb the heat-trapping gases scientists have linked to climate change."[11]

- December 2009: the Copenhagen Summit, a major attempt to move beyond the Kyoto agreement, though it was not successful.[3]

2010s

[edit]

- 2012 the Doha COP, Doha is considered one of the more important COPs as it attempted to establish targets for the second commitment period of Kyoto (the first commitment period having expired in 2012). Like Copenhagen, it was not generally considered successful.

- 2013: The Pacific Islands Forum issues the Majuro Declaration calling for further carbon emissions reductions.

- December 2015: The Paris Agreement. World leaders meet in Paris for the 21st Conference of the Parties of the UNFCCC. Paris was the first largely successful attempt to reach agreement for measures to supersede the Kyoto protocol. It now includes expectations for developing countries to act to mitigate climate change, rather than only requiring developed countries to do so. Developed countries are still expected to take the lead, and to supply financial support to other countries. Paris also contained provision for Climate change adaptation, with developed countries again expected to help support the developing world in taking adaptation related action.

- August 3, 2015: President Barack Obama introduces the Clean Power Plan in the United States to reduce air pollution, including greenhouse gas emissions.[12]

- April 2017: Protests against the climate change policy of President Donald Trump such as the March for Science and the 2017 People's Climate March occur.

- June 2017: President Donald Trump withdraws the United States from the Paris Agreement

- October 8, 2018: publication of the IPCC Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5 °C predicting dire environmental consequences if global warming is allowed to rise above approximately 1.5 °C.[13]

- April 28, 2019: Democratic Representatives Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Ed Markey introduce a resolution in the U.S. House of Representatives calling for a Green New Deal, causing little immediate change in policy but attracting considerable attention as an issue in the 2020 United States elections.[14]

- September 2019: UN Secretary-General António Guterres convenes the 2019 UN Climate Action Summit in an attempt to pressure countries to commit to greenhouse gas reductions of 45 percent by 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2050, but the talks are hindered by the absence of the two largest carbon emitters China and the United States.[9]

- December 1, 2019: The European Commission issues a European Green Deal to reduce Europe to climate neutrality by 2050.[15]

- December 2019: 25th Conference of Parties ends without any decisive action on climate change policy.[9]

2020s

[edit]- January 2021 Joe Biden signs an executive order for the United States to rejoin the Paris Agreement

- August 7, 2021: publication of the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report predicting that 1.5 °C warming within the next two decades is likely at current emissions levels and calls for drastic action to prevent further catastrophic warming.[9][16]

- October 31-November 12, 2021: The 26th COP is held in Edinburgh, United Kingdom, after being postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic It had been set to be the first COP to include a commitment to phase out coal power stations, but this was lessened at last minute.[17]

- November 2022: COP 27 was held in Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt, and led to the creatuion of the first loss-and-damage fund.[18]

- November 30 to December 13, 2023, The 28th COP was held in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. It ended with a historic commitment to transition away from fossil fuels, yet attracted criticism for not including the stronger "phase out" wording.[19]

National positions

[edit]The positions adopted by different nations in climate change negotiations often reflect the extent to which they are threatened by climate change, their level of dependency on fossil fuels for economic development, and the degree to which they are endowed with fossil fuels they can profitably extract, without needing to import. With the exception of a few Island nations, which feel highly threatened by rising sea levels and tend to consistently argue for strongly climate friendly policy, each nation's position has tended to vary over time. This reflects the personal preferences of whoever happens to have executive power during particular conferences, along with the shifting balance of power of various internal factions within each nation, each of which can have sharply different views on the best response to the climate change threat.[3] Strong climate friendly positions taken at international climate conferences can sometimes contrast with a nations slow progress in limiting its own Greenhouse gas emissions. The relative performance of the world's nations in limiting climate change within their own borders is reported on by the Climate Change Performance Index and by Climate Action tracker.[3][20]

United States

[edit]Since the late 1960s, the United States has at various times led efforts to develop political consensus for action against climate change. Yet it remains notorious for having one of the world's highest emissions per head figures. During the 2017 – 2021 Donald Trump administration, the USA had a climate change denier at the highest level of executive power, though climate science-informed policy continued to be enacted in parts of the country at state level. Joe Biden, who took over the presidency in January 2021, has been recognised for putting climate change at the heart of his policy agenda, though how effective this will prove remains to be seen.[3][21]

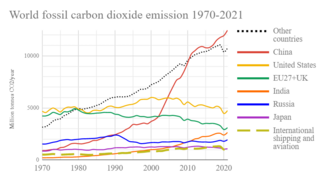

China

[edit]China is the world's biggest emitter of greenhouse gases, releasing almost twice as much GHG as the second largest emitter, the US. China is also the world's largest investor in renewable energy – in 2018 it invested $126 billion, almost half of the $279 billion invested across the entire world. China has always taken climate change seriously at international negotiations. Yet it has often strongly argued that western nations should take a greater share of the financial burden in helping developing countries to respond to climate change than they were willing to bear. An exception to this occurred in the build up to the Paris negotiations, where China took a more collaborative approach.[22][3]

European Union

[edit]Especially compared to the US, nations forming the European Union have had a mostly consistent position in favour of strong action to mitigate climate change. They have been steadily reducing greenhouse gas emissions, achieving on average a 23% reduction between 1990 – 2016. Though they are sometimes criticised for not having reduced emissions fast enough, given their capabilities, and for not doing enough to help less developed nations.[3]

Russia

[edit]Similar to Canada, Russia is both a net exporter of fossil fuels, and a country that could benefit from moderate global warming. Especially before 2010, Russian leaders would sometimes make dismissive statements about man made global warming, and could be somewhat obstructive to international climate change negotiations. Since 2010 however, Russia has become more supportive of climate change mitigation.[3]

Notes

[edit]- ^ One of the reasons being that in the early 1970s a significant minority of scientists were stating that the climate change threat was from global cooling rather than warming. From about 1940 until the early 1970s, there were indications of very slightly cooling of average temperatures. This was caused by a high concentration of atmospheric sulfate aerosols which had resulted from volcanic eruptions, and from industrial activity before controls to reduce sulphur emissions became widespread.

- ^ In addition to the normal collective action problems, other difficulties have included: 1) The fact that fossil fuel use has been common across the economy, unlike the relatively few firms that controlled manufacture of products containing the CFCs, which had been damaging the Ozone layer. 2. Incompatible views from different nations on the level of responsibility that highly developed countries had in assisting less developed controls to control their emissions without inhibiting their economic growth. 3.) Difficulty in getting humans to take significant action to limit a threat that is far away in the future. 4) The dilemma between the conflicting needs to reach agreements that could be accepted by all, versus the desirability for the agreement to have significant practical effect on human activity. See e.g. Dryzek (2011) Chpt. 3, and Dessler (2019) Chpt. 1, 4 & 5.

- ^ A "Scandinavian connection" was alleged by Nils-Axel Mörner who saw an early friendship of Palme and Bert Bolin as reasons for Bolin then being promoted as environmental steward in the Swedish government and later as first head of the IPCC

Citations

[edit]- ^ Oswald Spengler (1932). Man and Technics (PDF). Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0-8371-8875-X.

climatic changes have been thereby set afoot which imperil the land-economy of whole populations

- ^ Christiana Figueres; Tom Rivett-Carnac (2020). "Introduction". The Future We Choose: Surviving the Climate Crisis. Manilla Press. ISBN 978-1-838-770-82-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Andrew Dessler; Edward A Parson (2020). "1, 4, 5". The Science and Politics of Global Climate Change: A Guide to the Debate (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 26, 112, 175. ISBN 978-1-31663132-4.

- ^ Dryzek, John; Norgaard, Richard; Schlosberg, David, eds. (2011). "2". The Oxford Handbook of Climate Change and Society. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-956660-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Die Frühgeschichte der globalen Umweltkrise und die Formierung der deutschen Umweltpolitik(1950-1973) (Early history of the environmental crisis and the setup of German environmental policy 1950-1973), Kai F. Hünemörder, Franz Steiner Verlag, 2004 ISBN 3-515-08188-7

- ^ "The First World Climate Conference". Archived from the original on 28 September 2007.

- ^ a b "The Brandt Proposals: A Report Card, Energy and the Environment". Archived from the original on 18 January 2009. Retrieved 24 December 2008.

- ^ Jonathan Watts (2023-12-29). "World will look back at 2023 as year humanity exposed its inability to tackle climate crisis, scientists say". the Guardian. Retrieved 2024-01-03.

- ^ a b c d "Timeline: UN Climate Talks". Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved 2021-10-28.

- ^ "Byrd-Hagel Resolution (S. Res. 98) Expressing the Sense of the Senate Regarding Conditions for the US Signing the Global Climate Change Treaty". Nationalcenter.org. Archived from the original on 2 November 2006. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- ^ Broder, John (2009-06-26). "House Passes Bill to Address Threat of Climate Change". New York Times. Retrieved 2009-06-27.

- ^ "Climate change: Obama unveils Clean Power Plan". BBC News. 2015-08-03. Retrieved 2021-10-28.

- ^ "Climate change impacts worse than expected, IPCC 1.5 report warns". Environment. 2018-10-08. Archived from the original on February 27, 2021. Retrieved 2021-10-28.

- ^ "The Green New Deal Explained". Investopedia. Retrieved 2021-10-28.

- ^ "Europe's Green Deal plan unveiled". POLITICO. 2019-12-11. Retrieved 2021-10-28.

- ^ "Major climate changes inevitable and irreversible – IPCC's starkest warning yet". the Guardian. 2021-08-09. Retrieved 2021-10-28.

- ^ "Ratchets, phase-downs and a fragile agreement: how Cop26 played out". the Guardian. 2021-11-15. Retrieved 2023-12-28.

- ^ "Climate change: Five key takeaways from COP27". BBC News. 20 November 2022. Retrieved 2023-12-28.

- ^ "Failure of Cop28 on fossil fuel phase-out is 'devastating', say scientists". the Guardian. 2023-12-14. Retrieved 2023-12-28.

- ^ Climate Action tracker https://climateactiontracker.org/countries/

- ^ "Joe Biden invites 40 world leaders to virtual summit on climate crisis". The Guardian. 27 March 2021. Retrieved 25 April 2021.

- ^ Michael Safi Jason Burke, Michael Standaert, David Agren, Leyland Cecco, Adam Morton, Flávia Milhorance, Emmanuel Akinwotu (27 April 2021). "So what has the rest of the world promised to do about climate change?". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 April 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)