Theory of motivated information management

The theory of motivated information management (TMIM) is a social-psychological framework that examines the relationship between information management and uncertainty. TMIM has been utilized to describe the management of information regarding challenging, taboo, or sensitive matters. In regards to interpersonal information seeking, there are numerous routes and methods one can choose to take in order to obtain that information. TMIM analyzes whether an individual will engage in information seeking within the first place and also assess the role of the information provider. The theory posits that individuals are "motivated to manage their uncertainty levels when they perceive a discrepancy between the level of uncertainty they have about an important issue and the level of uncertainty they want."[citation needed] "TMIM distinguishes itself from other information-seeking theories in that it does not attribute the motivation of information seeking to a desire for uncertainty reduction; rather, the catalyst of information management in TMIM lies in the discrepancy between actual and desired uncertainty."[citation needed] In other words, someone may be uncertain about an important issue but decides not to engage or seek information because they are comfortable with that state and, therefore, desire it. People prefer certainty in some situations and uncertainty in other

While still fairly new,[as of?] TMIM has been incorporated to look at a variety of issues within a variety of contexts. This theory, although dealing with psychological actions, looks at communicative behavior and is applied in communication, specifically in the subfields of interpersonal and human communication.

Background

[edit]TMIM was first proposed in 2004 by Walid Afifi and Judith Weiner through their article, "Toward a Theory of Motivated Information Management."[1] A revision to the theory was put forth by Walid Afifi and Christopher Morse in 2009.[citation needed]

TMIM was developed to account for a person's active information management efforts in interpersonal communication channels.[2] The framework shares close ties to Brashers' uncertainty management theory, Babrow's problematic integration theory, Johnson and Meischkes' comprehensive model of information seeking and Bandura's social cognitive theory.[1] The revision also relies on Lazarus' appraisal theory of emotions.[3] TMIM stemmed out of a desire to bring together ideas and address limitations of existing frameworks on uncertainty. More specifically, it emphasizes the role played by efficacy beliefs, explicitly highlights the role played by the information provider in uncertainty management interactions, and improves communication research about uncertainty management decisions.[3]

Definition

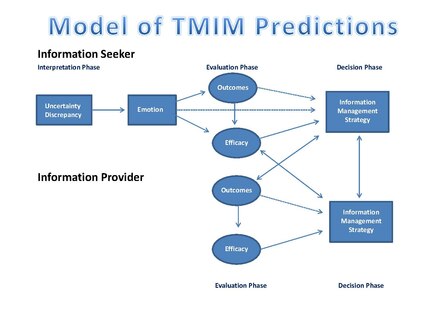

[edit]TMIM is a description of a three-phase process that individuals go through in deciding whether to seek or avoid information about an issue and a similar two-stage process that information providers go through in deciding what, if any, information to provide.[4]

TMIM's three-phase process consists of the interpretation, evaluation, and decision stages and the two-stage process is broken down by examining the role of the information seeker and information provider.

Phases

[edit]Process for the information seeker

[edit]This section contains instructions, advice, or how-to content. (June 2023) |

Interpretation phase

[edit]The first phase involves an assessment of uncertainty. According to TMIM, individuals experience uncertainty when they feel that they cannot predict what will happen with a particular issue or in a given situation. The difference between the amount of uncertainty a person has and the amount of uncertainty he or she desires to have about this issue is referred to as uncertainty discrepancy.[1] It serves as the motivation factor for the information seeking process.

TMIM originally proposed that uncertainty discrepancy caused anxiety due to a person's need for a balance between their desired and actual states of uncertainty.[4] The revised version, however, proposes that the discrepancy can create emotions other than anxiety, including shame, guilt or anger, among others.[3] Nevertheless, the emotion felt influences, and is followed by, an evaluation.

Evaluation phase

[edit]The evaluation phase focuses on mediation. It is used to facilitate the effect of the emotion by evaluating the expectations about the outcomes of an information search and the perceived abilities to gain the information sought after.[1] In other words, the individual weighs whether or not to seek additional information. This involves two general considerations central to most models of human behavior:[5]

- Outcome expectancy – individuals assess the pros and cons that come from seeking information about the issue.

- Efficacy assessments – individuals decide whether they are able to gather the information needed to manage their uncertainty discrepancy and then actually cope with it.

These two conditions will determine how someone seeks information. According to TMIM, individuals that experience feelings of efficacy are generally able to engage in the behavior or to accomplish the task at hand.[4] Unlike the broad conceptualizations of efficacy recognized by the comprehensive model of information seeking, the theory argues three very specific efficacy perceptions that are uniquely relevant to interpersonal communication episodes:[3]

- Communication efficacy – An individual's perception that they have the communication skills to successfully complete the task at hand.

- Coping efficacy – An individual's belief that they can or cannot cope with what information they might discover from seeking.

- Target efficacy – consist of two distinct components: target ability and target willingness. Thus, this is based on an individual's perception of the target person's ability and willingness to provide information that will reduce the uncertainty discrepancy.

The theory argues that outcome expectancy, which is an individual's assessments of the benefits and costs of information seeking, impact their efficacy judgments.[5] However, these assessments have little direct impact on the decision to seek information.[3] In other words, TMIM assigns efficacy as the primary direct predictor of that decision.

Decision phase

[edit]The decision phase is where individuals decide whether or not, to engage information. TMIM proposes three ways of doing so:

- Seek relevant information: Several studies have found that when individuals decide to seek information relevant to their uncertainty, they usually adopt a communication strategy to do so (such as passive, active, or interactive approaches).[1] TMIM's image of information managers is consistent with these findings. However, in cases in which individuals determine that seeking information is too costly, anxiety reduction is unlikely, or is otherwise likely to be unproductive, they will likely resort to other strategies.[1]

- Avoid relevant information: Rather than seeking information, individuals may sometimes choose to avoid relevant information. TMIM hypothesizes that individuals are most likely to avoid information if they consider information seeking risky due to the outcome, efficacy beliefs or both.[3] Some individuals would also avoid situations or people who may offer relevant information. This response is referred to as ‘active avoidance’ and essentially, the individual decides that “the reduction of the uncertainty related anxiety is likely to be more damaging than beneficial”.[1]

- Cognitive reappraisal: According to TMIM, individuals can also reduce the anxiety or emotion that activated the need for uncertainty management by changing their mindset (cognitive alteration).[1] Therefore, the individual reappraises “the perceived level of issue importance, the desired level of uncertainty, of the meaning of uncertainty".[3]

Process for information provider

[edit]

assesses the impact of how much information the target-provider would give and how they do so. The theory argues that the provider goes through similar evaluation and decision phases as the information seeker.[3] The provider considers the pros and cons of giving the seeker the sought-after information (outcome assessment) and their efficacy to do so. However, the efficacy perceptions are tailored toward the provider:

- Communication efficacy

- Coping efficacy

- Target efficacy

This assessment helps the provider choose whether to provide information to the seeker or not. During the decision phase, the provider also gets to determine how and in what way to convey the sought-after information. For example, the information provider can decide to respond to a seeker's request face-to-face or by email.

Application

[edit]Several studies have successfully tested TMIM.[citation needed] Specifically, the theory has accurately predicted whether people seek sexual health information from their partners (2006), what drives people to talk with their family about organ donation (2006) whether teenagers talk to their divorced or non-divorced parents about the parents’ relationship (2009), and whether adult children talk to their elderly parents about eldercare preferences (2011), among other issues. In all these cases, the theory has provided generally favorable results about its utility to predict individuals' information management decisions, but also experienced some limitations.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h Afifi &, W.; Weiner, J. (2004). "Toward a Theory of Motivated Information Management". International Communication Association. 14 (2): 167–190. doi:10.1093/ct/14.2.167.

- ^ Afifi, W. &; Weiner, J. (2006). "Seeking Information About Sexual Health: Applying the Theory of Motivated Information Management". International Communication Association. 32: 35–57. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2958.2006.00002.x.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Afifi, W.A. (2009). "Successes and challenges in understanding information seeking in interpersonal contexts. In Wilson, S. & Smith, S. (Eds)". New Directions in Interpersonal Communication. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE: 94–114.

- ^ a b c Theory of Motivated Information Management (Encyclopedia of Communication Theory ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. 2009.

- ^ a b Afifi, W. & Fowler, C. (2011). "Applying the Theory of Motivated Information to adult children's discussions of caregiving with again parents". Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 28 (4): 507–535. doi:10.1177/0265407510384896.