Studebaker

Badge used in the 1950s and 1960s | |

| Formerly | Studebaker Brothers Manufacturing Company |

|---|---|

| Industry | Automotive, manufacturing |

| Founded | February 1852 |

| Founders |

|

| Defunct | February 1968 |

| Fate | Merged with Packard to form the Studebaker-Packard Corporation Merged with Wagner Electric and Worthington Corporation to form Studebaker-Worthington Some naming and production rights, along with Studebaker's South Bend plant, acquired by the Avanti Motor Company |

| Successor | Studebaker-Packard Corporation Studebaker-Worthington |

| Headquarters | 635 S. Main St., South Bend, Indiana, U.S. 41°40′07″N 86°15′18″W / 41.66861°N 86.25500°W |

Key people | |

| Products | Automobiles (originally wagons, carriages and harnesses) |

Studebaker was an American wagon and automobile manufacturer based in South Bend, Indiana, with a building at 1600 Broadway, Times Square, Midtown Manhattan, New York City.[1][2][3][4] Founded in 1852 and incorporated in 1868[5] as the Studebaker Brothers Manufacturing Company, the firm was originally a coachbuilder, manufacturing wagons, buggies, carriages and harnesses.

Studebaker entered the automotive business in 1902 with electric vehicles and in 1904 with gasoline vehicles, all sold under the name "Studebaker Automobile Company". Until 1911, its automotive division operated in partnership with the Garford Company of Elyria, Ohio, and after 1909 with the E-M-F Company and with the Flanders Automobile Company. The first gasoline automobiles to be fully manufactured by Studebaker were marketed in August 1912.[6]: 231 Over the next 50 years, the company established a reputation for quality, durability and reliability.[7]

After an unsuccessful 1954 merger with Packard (the Studebaker-Packard Corporation) and failure to solve chronic postwar cashflow problems, the 'Studebaker Corporation' name was restored in 1962, but the South Bend plant ceased automobile production on December 20, 1963,[8] and the last Studebaker automobile rolled off the Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, assembly line on March 17, 1966. Studebaker continued as an independent manufacturer before merging with Wagner Electric in May 1967[9] and then Worthington Corporation in February 1968[10] to form Studebaker-Worthington.

History

[edit]German forebears

[edit]The ancestors of the Studebaker family descend from Solingen, Germany.[11] They arrived in America at the port of Philadelphia on September 1, 1736, on the ship Harle, (see Exhibit B) from Rotterdam, Netherlands, (see Exhibit A, p. 11), original manuscripts now in the Pennsylvania State Library at Harrisburg). This included Peter Studebaker and his wife Anna Margetha Studebaker, Clement Studebaker (Peter's brother) and his wife, Anna Catherina Studebaker and Heinrich Studebaker (Peter's cousin). (see Exhibit A, p. 11) In 1918, Albert Russel Erskine, Studebaker Corporation president, wrote the book, "History of the Studebaker Corporation", including the 1918 annual report, "Written for the information of the 3,000 stockholders of the Studebaker Corporation, the 12,000 dealers in its products living throughout the world, its 15,000 employees and numberless friends." (see Exhibit A, p. 9) This book was verified by lawyers and accountants and all board members and was a legal document. (see Exhibit A, p. 7) In the same book, Albert Russel Erskin, accurately wrote that Peter Studebaker was the "wagon-maker, which trade later became the foundation of the family fortune and the corporation which now bears his name." (see Exhibit A, p. 11)

"The tax list of York County, Pennsylvania, in 1798–9 showed among the taxable were Peter Studebaker Sr. and Peter Studebaker Jr. wagon-makers, which trade later became the foundation of the family fortune and the corporation which now bears his name." (see Exhibit D) "John Studebaker, father of the five brothers [that began the Studebaker Corporation] was the son of Peter Studebaker. (see Exhibit A, p. 13). John Clement Studebaker (son of Clement Studebaker and Sarah Rensel) was born February 8, 1799, Westmorland, PA, and died in 1877 in South Bend, St. Joseph, IN. John Studebaker (1799–1877) moved to Ohio in 1835 with his wife Rebecca (née Mohler) (1802–1887).

The five brothers

[edit]

The five sons were, in order of birth: Henry (1826–1895), Clement (1831–1901), John Mohler (1833–1917), Peter Everst (1836–1897) and Jacob Franklin (1844–1887). The boys had five sisters.[12] Photographs of the brothers and their parents are reproduced in the 1918 company history, which was written by Erskine after he became president, in memory of John M.,[13]: 5 whose portrait appears on the front cover.

18th-century colonial family business

[edit]In 1740 Peter Studebaker built his home on a property known as “Bakers Lookout”. (The home still stands in Hagerstown, Maryland.) The first Studebaker wagon factory was built in the same year next to the home. On Bakers Lookout Peter, master of the German Cutler Guild, built the first Studebaker home, the first Studebaker wagon factory where he began forging and tempering steel and seasoning wood in the colonies. Peter Studebaker built the first Studebaker mill and a wagon road. Broadfording Wagon Road was built to run through the property. Peter owned property on both sides of the Conococheague Creek, so he built a bridge over the creek in 1747. Peter began the family business on the Bakers Lookout property where he made his home and built the first Studebaker wagon factory. In this factory, Peter manufactured everything, all necessities including products he made in Solingen, Germany, and naturally wagons. Bakers Lookout, the 1740, 100-acre land patent, Hagerstown, Maryland, was the first of many land patents to be acquired by Peter Studebaker. Peter purchased approximately 1500 acres in what is now known state of Maryland. The home still stands today and is proof of the advanced technology of Peter Studebaker. (see Bakers Lookout Peter Studebakers 1740 home website)

In 1747 Peter Studebaker built a road through his owned properties known as Broadfording Wagon Road. The road he built carried heavy traffic to Bakers Lookout's wagon and forging services that were instrumental to expand the west. The Maryland Historical Trust WA-I-306 writes 04/03/2001, that this road was "One of Washington County's earliest thoroughfares, Broadfording (Wagon) Road was already in existence in 1747." (see Exhibit I) The wagon transportation industry boomed. On the property, Broadfording Wagon Road built in 1740 by Peter Studebaker, went directly through the property to allow access from the home to the factory and to the mill.

Although Peter Studebaker's life in the colonies was short, less than 18 years, the family business flourished through his descendants (see Exhibit M) and apprentices expanded the vast land holdings enlarging the Studebaker family business and its industrious wagon-making region. Peter's trade secrets were passed from father to son, generation to generation. The Studebaker family business plan, purchasing, again and again, vast amounts of land, on which they built industrious farms with mills and wagon making facilities and wagon selling facilities, each identical to the Bakers Lookout situation, industrious farms, much acreage, on which one finds the necessary resources, lumber, iron ore, oil shale and land selected with stream, spring, or river to hydropower factories, mills and equipment.[14] Peter's technology-enabled expansion of the family business through the famous Conestoga and Prairie Schooner wagon designs. Peter's trade was the stepping-stone that expanded the transportation industry. Thomas E. Bonsall, wrote "Much more than the story of a family business; it is also, in microcosm, the story of the industrial development of America." Peter Studebaker died in the mid-1750s.

End of horse-drawn era

[edit]John M. Studebaker had always viewed the automobile as complementary to the horse-drawn wagon, pointing out that the expense of maintaining a car might be beyond the resources of a small farmer. In 1918, when Erskine's history of the firm was published, the annual capacity of the seven Studebaker plants was 100,000 automobiles, 75,000 horse-drawn vehicles, and about $10,000,000 worth of automobile and vehicle spare parts ($202,566,372 in 2023 dollars [15]).[13]: 85 In the preceding seven years, 466,962 horse-drawn vehicles had been sold, as against 277,035 automobiles,[13]: 87 but the trend was all too clear. The regular manufacture of horse-drawn vehicles ended when Erskine ordered the removal of the last wagon gear in 1919.[16]: 90 To its range of cars, Studebaker would now add a truck line to replace the horse-drawn wagons. Buses, fire engines, and even small rail locomotive-kits[17] were produced using the same powerful six-cylinder engines.

Studebaker automobiles 1897–1966

[edit]In the beginning

[edit]

In 1895, John M. Studebaker's son-in-law Fred Fish urged for development of 'a practical horseless carriage'. When, on Peter Studebaker's death, Fish became chairman of the executive committee in 1897, the firm had an engineer working on a motor vehicle.[16]: 66 At first, Studebaker opted for electric (battery-powered) over gasoline propulsion. While manufacturing its own Studebaker Electric vehicles from 1902 to 1911, the company entered into body-manufacturing and distribution agreements with two makers of gasoline-powered vehicles, Garford of Elyria, Ohio, and the Everitt-Metzger-Flanders (E-M-F) Company of Detroit and Walkerville, Ontario. Studebaker began making gasoline-engined cars in partnership with Garford in 1904.[18]

Studebaker marque established in 1911

[edit]

In 1910, it was decided to refinance and incorporate as the Studebaker Corporation, which was concluded on February 14, 1911, under New Jersey laws.[13]: p.63 The company discontinued making electric vehicles that same year.[16]: 71 The financing was handled by Lehman Brothers and Goldman Sachs who provided board representatives including Henry Goldman whose contribution was especially esteemed.[13]: 76

After taking over E-M-F's Detroit facilities, Studebaker sought to remedy customer dissatisfaction complaints by paying mechanics to visit each disgruntled owner and replace defective parts in their vehicles, at a total cost of US$1 million ($15,209,302 in 2023 dollars[15]). The worst problem was rear-axle failure. Hendry comments that the frenzied testing resulted in Studebaker's aim to design 'for life'—and the consequent emergence of "a series of really rugged cars... the famous Big Six and Special Six" listed at $2,350 ($35,742 in 2023 dollars [15]).[6]: 231 From that time, Studebaker's own marque was put on all new automobiles produced at the former E-M-F facilities as an assurance that the vehicles were well built.

In 1913, the company experienced the first major labor strike in the automotive industry, the 1913 Studebaker strike.

Engineering advances from WWI

[edit]The corporation benefited from enormous orders cabled by the British government at the outbreak of World War I. They included 3,000 transport wagons, 20,000 sets of artillery harness, 60,000 artillery saddles, and ambulances, as well as hundreds of cars purchased through the London office. Similar orders were received from the governments of France and Russia.[13]: 79

The 1913 six-cylinder models were the first cars to employ the important advancement of monobloc engine casting which became associated with a production-economy drive in the years of the war. At that time, a 28-year-old university graduate engineer, Fred M. Zeder, was appointed chief engineer. He was the first of a trio of brilliant technicians, with Owen R. Skelton and Carl Breer, who launched the successful 1918 models, and were known as "The Three Musketeers".[6]: 234 They left in 1920 to form a consultancy, later to become the nucleus of Chrysler Engineering. The replacement chief engineer was Guy P. Henry, who introduced molybdenum steel,[6]: 236 an improved clutch design,[19] and presided over the six-cylinders-only policy favored by new president Albert Russel Erskine, who replaced Fred Fish in July 1915.[6]: 234

First auto proving ground

[edit]In 1925, the corporation's most successful distributor and dealer Paul G. Hoffman came to South Bend as vice president in charge of sales. In 1926, Studebaker became the first automobile manufacturer in the United States to open a controlled outdoor proving ground on which, in 1937, would be planted 5,000 pine trees in a pattern that spelled "STUDEBAKER" when viewed from the air.[20] Also in 1926, the last of the Detroit plant was moved to South Bend under the control of Harold S Vance, vice president in charge of production and engineering. That year, a new small car, the Erskine Six was launched in Paris, resulting in 26,000 sales abroad and many more in America.[16]: 91 By 1929, the sales list had been expanded to 50 models and business was so good that 90% of earnings were being paid out as dividends to shareholders in a highly competitive environment. However, the end of that year ushered in the Great Depression that resulted in many layoffs and massive national unemployment for several years.

Facilities in the 1920s

[edit]

Studebaker's total plant area in Indiana was 225 acres (0.91 km2), spread over three locations, with buildings occupying 7.5 million square feet of floor space. Annual production capacity was 180,000 cars, requiring 23,000 employees.[6]: 237

The original South Bend vehicle plant continued to be used for small forgings, springs, and making some body parts. Separate buildings totaling over one million square feet were added in 1922–1923 for the Light, Special, and Big Six models. At any one time, 5,200 bodies were in process. South Bend's Plant 2 made chassis for the Light Six and had a foundry of 575,000 sq ft (53,400 m2), producing 600 tons of castings daily.[6]: 236

Plant 3 at Detroit made complete chassis for Special and Big Six models in over 750,000 sq ft (70,000 m2) of floor space and was located between Clark Avenue and Scotten Avenue south of Fort Street.[21][22] Plant 5 was the service parts store and shipping facility, plus the executive offices of various technical departments.[6]: 236 The Detroit facilities were moved to South Bend in 1926,[16]: 91 except that the Piquette Avenue Plant (Plant 10) was retained for assembly of the Erskine between 1927 and 1929 and the Rockne (1931–1933).[23]

Plant 7 was at Walkerville, Ontario, Canada, where complete cars were assembled from components that had been shipped from South Bend and Detroit factories or locally made in Canada, and is in close proximity to the current Ford Windsor Engine Factory. Output was designated for the Canadian (left-hand drive) and British Empire (right-hand drive) trade. By locating it there, Studebaker could advertise the cars as "British-built" and qualify for reduced tariffs.[6]: 237 This manufacturing facility had been acquired from E-M-F in 1910 (see above). By 1929, it had been the subject of $1.25 million investment and was providing employment that supported 500 families.[24]

Impact of the 1930s depression

[edit]

Few industrialists were prepared for the Wall Street Crash of October 1929. Though Studebaker's production and sales had been booming, the market collapsed and plans were laid for a new, small, low-cost car—the Rockne. However, times were too bad to sell even inexpensive cars. Within a year, the firm was cutting wages and laying off workers. Company president Albert Russel Erskine maintained faith in the Rockne and rashly had the directors declare huge dividends in 1930 and 1931. He also acquired 95% of the White Motor Company's stock at an inflated price and in cash. By 1933, the banks were owed $6 million, ($141,223,650 in 2023 dollars [15]) though current assets exceeded that figure. On March 18, 1933, Studebaker entered receivership. Erskine was pushed out of the presidency in favor of more cost-conscious managers. Erskine committed suicide on July 1, 1933, leaving successors Harold Vance and Paul Hoffman to deal with the problems.[16]: 96–98

By December 1933, the company was back in profit with $5.75 million working capital and 224 new Studebaker dealers, while the purchase of White was cancelled.[16]: 99 With the substantial aid of Lehman Brothers, full refinancing and reorganization was achieved on March 9, 1935. A new car was put on the drawing boards under chief engineer Delmar "Barney" Roos—the Champion. Its final styling was designed by Virgil Exner and Raymond Loewy. The Champion doubled the company's previous-year sales when it was introduced in 1939.[16]: 109

World War II

[edit]From the 1920s to the 1930s, the South Bend company had originated many style and engineering milestones, including the Light Four, Light Six, Special Six, Big Six models, the Dictator, the record-breaking Commander and President, followed by the 1939 Champion. During World War II, Studebaker produced the Studebaker US6 truck in great quantity and the unique M29 Weasel cargo and personnel carrier. Studebaker ranked 28th among United States corporations in the value of wartime production contracts.[25][26] An assembly plant in California, Studebaker Pacific Corporation, built engine assemblies and nacelles for B-17s and PV-2 Harpoons.[27] After cessation of hostilities, Studebaker returned to building automobiles.

Post-WWII styling

[edit]

Studebaker prepared well in advance for the anticipated postwar market and launched the slogan "First by far with a post-war car". This advertising premise was substantiated by Virgil Exner's designs,[28] notably the 1947 Studebaker Starlight coupé, which introduced innovative styling features that influenced later cars, including the flatback "trunk" instead of the tapered look of the time, and a wrap-around rear window. For 1950 and 1951, the Champion and Commander adopted a polarizing appearance from Exner's concepts, and were applied to the 1950 Studebaker Starlight coupe.[29] The new trunk design prompted a running joke that one could not tell if the car was coming or going, and appeared to be influenced by the Lockheed P-38 Lightning, particularly by the shortened fuselage with wrap around canopy.[28] During the war the Studebaker Chippewa Factory was the primary location for aircraft engines used in the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress and the marketing department attempted to evoke a reference to their contribution to the war effort.

Industry price war brings on crisis

[edit]Studebaker's strong postwar management team including president Paul G Hoffman and Roy Cole (vice president, engineering) had left by 1949[6]: 252 and was replaced by more cautious executives who failed to meet the competitive challenge brought on by Henry Ford II and his Whiz Kids. Massive discounting in a price war between Ford and General Motors, which began with Ford's massive increase in production in the spring of 1953—part of Ford's postwar expansion program aimed at restoring it to the position of the largest car maker which GM had held since 1931—could not be equaled by the independent carmakers, for whom the only hope was seen as a merger of Studebaker, Packard, Hudson, and Nash into a fourth giant combine after Chrysler. This had been unsuccessfully attempted by George W. Mason. In this scheme, Studebaker had the disadvantage that its South Bend location would make consolidation difficult. Its labor costs were also the highest in the industry.[6]: 254

Merger with Packard

[edit]Ballooning labor costs (the company had never had an official United Auto Workers (UAW) strike and Studebaker workers and retirees were among the highest paid in the industry), quality control issues, and the new-car sales war between Ford and General Motors in the early 1950s wrought havoc on Studebaker's balance sheet.[6]: 254–55 Professional financial managers stressed short-term earnings rather than long-term vision. Momentum was sufficient to keep going for another 10 years, but stiff competition and price-cutting by the Big Three doomed the enterprise.

From 1950 Studebaker declined rapidly, and by 1954 was losing money. It negotiated a strategic takeover by Packard, a smaller but less financially troubled car manufacturer. However, the cash position was worse than it had led Packard to believe, and by 1956, the company (renamed Studebaker-Packard Corporation and under the guidance of CEO James J. Nance) was nearly bankrupt, though it continued to make and market both Studebaker and Packard cars until 1958.[6]: 254 The "Packard" element was retained until 1962, when the name reverted to "Studebaker Corporation".

Contract with Curtiss-Wright

[edit]A three-year management contract was made by CEO Nance with aircraft maker Curtiss-Wright in 1956[30] with the aim of improving finances due to Studebaker's experience building aircraft engines during the war and military grade trucks.[6] C-W's president, Roy T. Hurley, attempted to reduce labor costs. Under C-W's guidance, Studebaker-Packard also sold the old Detroit Packard plant and returned the then-new Packard plant on Conner Avenue (where Packard production had moved in 1954, at the same time Packard took its body-making operations in house after its longtime body supplier, Briggs Manufacturing Company, was acquired by Chrysler in late 1953) to its lessor, Chrysler. The company became the American importer for Mercedes-Benz, Auto Union, and DKW automobiles and many Studebaker dealers sold those brands, as well. C-W gained the use of idle car plants and tax relief on their aircraft profits while Studebaker-Packard received further working capital to continue car production.

Last automobiles produced

[edit]The automobiles that came after the diversification process began, including the redesigned compact Lark (1959) and the Avanti sports car (1962), were based on old chassis and engine designs. The Lark, in particular, was based on existing parts to the degree that it even used the central body section of the company's 1953–58 cars, but was a clever enough design to be popular in its first year, selling over 130,000 units and delivering a $28.6 million profit to the automaker ($298,928,767 in 2023 dollars[15]). "S-P rose from 56,920 units in 1958 to 153,844 in 1959."[31]

However, Lark sales began to drop precipitously after the Big Three manufacturers introduced their own compact models in 1960, and the situation became critical once the so-called "senior compacts" debuted for 1961. The Lark had provided a temporary reprieve, but nothing proved enough to stop the financial bleeding.

A labor strike occurred at the South Bend plant[32] starting on January 1, 1962, and lasting 38 days.[33] The strike came to an end after an agreement was reached between company president Sherwood H. Egbert and Walter P. Reuther, president of the UAW.[34] Despite a sales uptick in 1962, continuing media reports that Studebaker was about to leave the auto business became a self-fulfilling prophecy as buyers shied away from the company's products for fear of being stuck with an "orphan". NBC reporter Chet Huntley made a television program called "Studebaker – Fight for Survival" which aired on May 18, 1962.[35] By 1963, all of the company's automobiles and trucks were selling poorly.

Exit from auto business

[edit]Closure of South Bend plant, 1963

[edit]After insufficient initial sales of the 1964 models and the ousting of president Sherwood Egbert, on December 9, 1963, the company announced the closure of the aging South Bend plant.[36] The last Larks and Hawks were assembled on December 20,[8][37] and the last Avanti was assembled on December 26. To fulfill government contracts, production of military trucks and Zip Vans for the United States Postal Service continued into early 1964. The engine foundry remained open until the union contract expired in May 1964. The supply of engines produced in the first half of 1964 supported Zip Van assembly until the government contract was fulfilled, and automobile production at the Canadian plant until the end of the 1964 model year. The Avanti model name, tooling, and plant space were sold off to Leo Newman and Nate Altman, a longtime South Bend Studebaker-Packard dealership. They revived the car in 1965 under the brand name "Avanti II". (See main article Avanti (car).) They likewise purchased the rights and tooling for Studebaker's trucks, along with the company's vast stock of parts and accessories. The plant, alongside Studebaker's General Products Division, was bought by Kaiser Jeep Corporation who used it to produce military vehicles. That unit formed the nucleus for what would later become AM General Corporation, which today is the world’s largest producer of tactical wheeled vehicles.[38] Nevertheless, as Newman and Altman decided not to progress with any Studebaker truck production, the tooling was then sold off again to Kaiser Jeep in late 1965, which continued producing parts for Studebaker trucks for a few more years. Some '1965' model Champ trucks were built in South America using completely knocked-down kits and left-over parts.[citation needed] These models used a different grille from all previous Champ models.

The closure of the South Bend plant hit the community particularly hard, since Studebaker was the largest employer in St. Joseph County, Indiana. Nearly a quarter of the South Bend work force was African-American.[39]

Closure of Hamilton plant, 1966

[edit]

Limited automotive production was consolidated at the company's last remaining production facility in Hamilton, Ontario, which had always been profitable and where Studebaker produced cars until March 1966 under the leadership of Gordon Grundy. It was projected that the Canadian operation could break even on production of about 20,000 cars a year, and Studebaker's announced goal was 30,000–40,000 1965 models.[citation needed] While 1965 production was just shy of the 20,000 figure, the company's directors felt that the small profits were not enough to justify continued investment. Rejecting Grundy's request for funds to tool up for 1967 models, Studebaker left the automobile business on March 17, 1966, after an announcement on March 4.[40] A turquoise and white Cruiser sedan[41] was the last of fewer than 9,000 1966 models manufactured (of which 2,045 were built in the 1966 calendar year[42]). In reality, the move to Canada had been a tactic by which production could be slowly wound down and remaining dealer franchise obligations honored.[citation needed] The 1965 and 1966 Studebaker cars used "McKinnon" engines sourced from General Motors Canada Limited, which were based on Chevrolet's 230-cubic-inch six-cylinder and 283 cubic-inch V8 engines when Studebaker-built engines were no longer available.[citation needed]

The closure adversely affected not only the plant's 700 employees, who had developed a sense of collegiality around group benefits such as employee parties and day trips, but the city of Hamilton as a whole; Studebaker had been Hamilton's 10th-largest employer.[41]

Potential link with Nissan and Toyota

[edit]In 1965, Gordon Grundy of Studebaker Canada was sent by Studebaker management to Japan to investigate potential links with Nissan and Toyota, to sell their vehicles badged as Studebakers. While Grundy was negotiating with Nissan to possibly import the Nissan Cedric, the Studebaker board found out about the Toyota Century, which was not introduced until February 1968, and then the attorney representing the board, former United States Vice President Richard Nixon, asked Grundy to contact Toyota, as well. Toyota was insulted at being Studebaker's second choice, and when word got out to Nissan that Grundy was also speaking with Toyota executives, Nissan ended negotiations, leaving Grundy empty-handed.[43]

Network and other assets

[edit]Many of Studebaker's dealers either closed, took on other automakers' product lines, or converted to Mercedes-Benz dealerships following the closure of the Canadian plant. Studebaker's General Products Division, which built vehicles to fulfill defense contracts, was acquired by Kaiser Industries, which built military and postal vehicles in South Bend. In 1970, American Motors (AMC) purchased the division, which still exists today as AM General.

The grove of 5,000 trees planted on the proving grounds in 1937, spelling out the Studebaker name, still stands and has proven to be a popular topic on such satellite photography sites as Google Earth.[44] The proving grounds were acquired by Bendix in 1966[45] and Bosch in 1996. After Bosch closed its South Bend operation in 2011,[46][47] a part of the proving ground was retained and, as of April 2013[update], has been restored to use under the name "New Carlisle Test Facility".[45][48]

For many years a rumor persisted of the existence of a Studebaker graveyard. The rumor was later confirmed to be true when the remains of many prototype automobiles and a few trucks were discovered at a remote, heavily wooded site bounded by the proving grounds' high-speed oval. Most of the prototypes were left to rot in direct contact with the ground and full exposure to the weather and falling trees. Attempts to remove some of these rusting bodies resulted in the bodies crumbling under their own weight as they were moved, so now they exist only in photographs.

However, there were a few notable exceptions. A few of the prototypes were rescued. The only example of a never-produced 1947 Champion wood-sided station wagon was restored and is on display at the Studebaker National Museum.

Another prototype initially slated for disposal at the proving grounds escaped the fate of the others. In late 1952 Studebaker produced one 1953 Commander convertible as an engineering study to determine if the model could be profitably mass-produced. The car was based on the 1953 2-door hardtop coupe. The car was later modified to 1954-model specifications, and was occasionally driven around South Bend by engineers. Additional structural reinforcements were needed to reduce body flexure. Even though the car was equipped with the 232 cu. in. V-8, the added structural weight increased the car's 0-60 mph acceleration time to an unacceptable level. In addition, the company did not have the financial resources to add another body type to the model line. The company's leadership mistakenly thought the 2-door sedans, 4-door sedans, and 1954 Conestoga wagon would sell better than the 2-door coupes, so the company's resources were focused on production of the sedans and the wagon. When the prototype convertible was no longer needed, engineer E. T. Reynolds ordered the car to be stripped and the body sent to the secret graveyard at the proving grounds. A non-engineering employee requested permission to purchase the complete car, rather than see it rot away with the other prototypes. Chief engineer Gene Hardig discussed the request with E. T. Reynolds. They agreed to let the employee purchase the car on the condition that the employee never sell it. In the 1970s, the car was re-discovered behind a South Bend gas station and no longer owned by the former employee. After eventually passing through several owners, the car is now in a private collection of Studebaker automobiles.

In May 1967, Studebaker and its diversified units were merged with Wagner Electric.[49] In November 1967, Studebaker was merged with the Worthington Corporation to form Studebaker-Worthington.[50][51] The Studebaker name disappeared from the American business scene in 1979, when McGraw-Edison acquired Studebaker-Worthington, except for the still existing Studebaker Leasing, based in Jericho, NY. McGraw-Edison was itself purchased in 1985 by Cooper Industries, which sold off its auto-parts divisions to Federal-Mogul some years later. As detailed above, some vehicles were assembled from left-over parts and identified as Studebakers by the purchasers of the Avanti brand and surplus material from Studebaker at South Bend.

Diversified activities

[edit]By the early 1960s, Studebaker had begun to diversify away from automobiles. Numerous companies were purchased, bringing Studebaker into such diverse fields as the manufacture of tire studs and missile components.

The company's 1963 annual report listed the following divisions:

- Clarke – Floor Machine Division, Muskegon, Michigan

- CTL – Missile/Space Technology Division, Cincinnati, Ohio

- Franklin – Appliance Division, Minneapolis, Minnesota (home office; other locations also in Minnesota, Iowa, and Ontario). Manufactured private label kitchen and laundry appliances for major retailers until it was sold to White Consolidated Industries.[52]

- Gravely Tractor – Tractors Division, Dunbar, West Virginia, and Albany, Georgia

- International – South Bend, Indiana (handled business matters for all divisions doing business overseas)

- Onan – Engine/Generator Division, Minneapolis, Minnesota

- Paxton Automotive – automobile superchargers

- STP – Chemical Compounds Division, Des Plaines, Illinois, and Santa Monica, California. Produced automotive engine additives.

- Schaefer – Commercial Refrigeration Division, Minneapolis, Minnesota, and Aberdeen, Maryland

- Studebaker of Canada – Automotive Manufacturing, Hamilton, Ontario

- SASCO – Studebaker Automotive Sales Corp., South Bend, Indiana.

- Studegrip – Tire Stud Division, South Bend, Indiana, Jefferson, Iowa, and Minneapolis, Minnesota

- Trans International Airlines – founded by Kirk Kerkorian

Having built the Wright R-1820 under license during World War II, Studebaker also attempted to build what would perhaps have been the largest aircraft piston engine ever built. With 24 cylinders in an "H" configuration, a bore of 8 in (203 mm) and stroke of 7.75 in (197 mm), displacement would have been 9,349 cubic inches (153.20 L), hence the H-9350 designation. It was not completed.[53]

Attempts at revival

[edit]Studebaker XUV (2003)

[edit]In 2003, Avanti Motor Company revealed the Studebaker XUV concept at the Chicago Auto Show. The company was able to use the Studebaker name since it had also purchased the rights to Studebaker Trucks alongside the Avanti tooling back in 1963. The large SUV was built on the chassis of a Ford Super-Duty and was powered by a 310-horsepower Ford V10 engine. Due to its close resemblance to the Hummer H2, General Motors filed a lawsuit against Avanti, claiming the XUV was a blatant copy of the H2. A revised design was shown at the 2004 Chicago Auto Show, although did not make production due to Avanti CEO Michael Kelly's arrest in 2006 and subsequent imprisonment.[54]

Ric Reed ownership (2012-)

[edit]In 2001, the rights to the Studebaker name were acquired by Colorado based clothing shop owner Ric Reed, who revealed his plans for the company in 2011. Firstly planned to be used on a retro-modern pickup truck reminiscent of the Champ, Reed later intended to use the brand name on a range of Chinese-made petrol and electric scooters, before progressing onto producing hybrid cars using the Lark, Hawk and president model names.[55][56] Reportedly, the cars were to use a Hydristor, a hydraulic transistor device originally invented by Tom Kasmer for use in a DeLorean sports car.[57] Despite intentions of restarting production in the United States, the proposal did not come to fruition.

Advertisements and logos

[edit]- Advertisements and Logos

-

1902 advertisement for horse-drawn vehicles

-

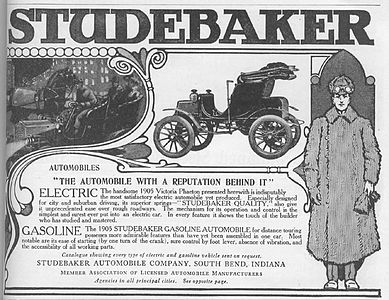

1905 advertisement for electric and gasoline-powered cars

-

1909 advertisement for new and used cars

-

1924 illuminated tiled display for Big Six touring car in Seville

-

Studebaker "turning wheel" badge on cars produced 1912–1934

-

1917 Studebaker logo

Studebaker factories

[edit]South Bend, Indiana

[edit]Downtown location

[edit]635 S. Lafayette Blvd., South Bend, IN[58]

- manufactured conestoga wagons, horse-drawn carriages, electric cars, automobiles

Clement and Henry Studebaker Jr., became blacksmiths and foundrymen in South Bend, Indiana, in February 1852.[6]: 229 [45] They first made metal parts for freight wagons and later expanded into the manufacture of complete wagons. At this time, John M. was making wheelbarrows in Placerville, California. The site of his business is California Historic Landmark #142 at 543 Main St, Placerville.[59]

The first major expansion in Henry and Clem's South Bend business came from their being in the right place to meet the needs of the California Gold Rush that began in 1849. From his wheelbarrow enterprise at Placerville, John M. had amassed $8,000 ($292,992 in 2023 dollars[15]). In April 1858, he quit and moved out to apply this to financing the vehicle manufacturing of H & C Studebaker, which was already booming because of an order to build wagons for the US Army. In 1857, they had also built their first carriage—"Fancy, hand-worked iron trim, the kind of courting buggy any boy and girl would be proud to be seen in".[16]: 24

That was when John M. bought out Henry's share of the business. Henry was deeply religious and had qualms about building military equipment. The Studebakers were Dunkard Brethren, conservative German Baptists,[60] a religion that viewed war as evil. Longstreet's official company history simply says, "Henry was tired of the business. He wanted to farm. The risks of expanding were not for him".[16]: 26 Expansion continued from manufacture of wagons for westward migration, as well as for farming and general transportation. During the height of westward migration and wagon train pioneering, half of the wagons used were Studebakers. They made about a quarter of them, and manufactured the metal fittings for other builders in Missouri for another quarter-century.

The fourth brother, Peter E, was running a successful general store in Goshen, Indiana, which was expanded in 1860 to include a wagon distribution outlet.[16]: 28 A major leap forward came from supplying wagons for the Union Army in the Civil War (1861–1865). By 1868, annual sales had reached $350,000 ($11,868,889 in 2023 dollars [15]).[6]: 229 That year, the three older brothers formed the Studebaker Brothers Manufacturing Company—Clem (president), Peter (secretary), and John M. (treasurer).[16]: 38 By this time, the factory had a spur line to the Lake Shore railroad and, with the Union Pacific Railroad finished, most wagons were now dispatched by rail and steamship.

World's largest vehicle house

[edit]

In 1875, the youngest brother, 30-year-old Jacob, was brought into the company to take charge of the carriage factory, making sulkies and five-glass landaus. Following a great fire in 1874, which destroyed two-thirds of the entire works, they had rebuilt in solid brick, covering 20 acres (81,000 m2) and were now "The largest vehicle house in the world".[16]: 43 Customers could choose from Studebaker sulkies, broughams, clarences, phaetons, runabouts, victorias, and tandems. For $20,000, a four-in-hand for up to a dozen passengers, with red wheels, gold-plated lamps, and yellow trim, could be had.

In the 1880s, roads started to be surfaced with tar, gravel, and wooden blocks. In 1884, when times were hard, Jacob opened a carriage sales and service operation in a fine new Studebaker Building on Michigan Avenue, Chicago. The two granite columns at the main entrance, 3 ft 8 in (1.12 m) in diameter and 12 ft 10 in (3.91 m) high, were said to be the largest polished monolithic shafts in the country.[61] Three years later, Jacob died, the first death among the brothers.

In 1889, incoming President Harrison ordered a full set of Studebaker carriages and harnesses for the White House.[62] As the 20th century approached, the South Bend plant "covered nearly 100 acres (0.40 km2) with 20 big boilers, 16 dynamos, 16 large stationary engines, 1000 pulleys, 600 wood- and iron-working machines, 7 mi (11 km) of belting, dozens of steam pumps, and 500 arc and incandescent lamps making white light over all".[16]: 54 The worldwide economic depression of 1893 caused a dramatic pause in sales and the plant closed down for five weeks, but industrial relations were good and the organized workforce declared faith in their employer. Studebaker would end the nineteenth century as the largest buggy and wagon works in the world, and by 1900, with around 3,000 workers, the plant in South Bend was producing over 100,000 horse-drawn vehicles of all types yearly.

The wagons pulled by the Budweiser Clydesdales are Studebaker wagons modified to carry beer, originally manufactured circa 1900.[63]

Family association continues

[edit]The five brothers died between 1887 and 1917 (John Mohler was the last to die).[64] Their sons and sons-in-law remained active in the management, most notably lawyer Fred Fish after his marriage to John M's daughter Grace in 1891.[65] "Col. George M Studebaker, Clement Studebaker Jr, J M Studebaker Jr, and [Fred Sr's son] Frederick Studebaker Fish served apprenticeships in different departments and rose to important official positions, with membership on the board."[13]: 41 Erskine adds sons-in-law Nelson J Riley, Charles A Carlisle, H D Johnson, and William R Innis.

Chippewa Factory

[edit]701 W Chippewa Ave, South Bend, IN[58]

Due to the war effort, and the capacity of the Downtown Facility was dedicated to Studebaker US6 truck and M29 Weasel production, the Chippewa Factory was built south of the city to initially manufacture Wright R-2600 Twin Cyclone aircraft engines to be installed in the North American B-25 Mitchell. Construction began January 1941 and completed in June 1942. Due to logistics challenges, the initial order was cancelled, and Studebaker was asked to build Wright R-1820 Cyclone aircraft engines instead. Retooling of the factory commenced and by January 1944 was the exclusive location of the Wright R-1820 installed in the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress.

After the war ended, the factory was idled until the Korean War began, and the M35 series 2½-ton 6×6 cargo truck resumed in 1950, and the M54 5-ton 6x6 truck was also manufactured at this location. Ownership of the factory changed hands a few times, but the M35 and M54 stayed in production until they were replaced by the FMTV in 1989.

Chicago, Illinois

[edit]5555 S. Archer Ave, Chicago, IL

During World War II, the plant produced aircraft engines for the B-17 Flying Fortress starting in January 1944 until the August 9, 1945, announcement for the building sale. Studebaker built 63,789 engines at the plant and each had nearly 8,000 finished parts. The aircraft were equipped with engines known as the Studebaker-built R-1820. The plant's main building, just west of Midway Airport, contained 782,988 square feet and sat on a 50-acre site. Although, engine items were fabricated and produced in the Chicago plant, they were sent to South Bend, Indiana for final assembly.[66] The plant was acquired by Western Electric to produce telephones that were already in backlog orders because of their war efforts.

Detroit, Michigan

[edit]4333 W Fort St, Detroit, MI

461 Piquette Street, Detroit, MI

6230 John R St, Detroit, MI (E-M-F)

- Manufactured automobiles

E-M-F and Flanders

[edit]Studebaker's agreement with the E-M-F Company, made in September 1908,[13]: 47 was a different relationship, one John Studebaker had hoped would give Studebaker a quality product without the entanglements found in the Garford relationship, but this was not to be. Under the terms of the agreement, E-M-F would manufacture vehicles and Studebaker would distribute them exclusively through its wagon dealers.

The E-M-F gasoline-powered cars proved disastrously unreliable, causing wags to say that E-M-F stood for Every Morning Fix-it, Easy Mark's Favorite, and the like.[6]: 231 Compounding the problems was the infighting between E-M-F's principal partners, Everitt, Flanders, and Metzger. Eventually in mid-1909, Everitt and Metzger left to start a new enterprise.[67]: 88 Flanders also quit and joined them in 1912, but the Metzger Motor Car Co could not be saved from failure by renaming it the Flanders Automobile Company.

Studebaker's president, Fred Fish, had purchased one-third of the E-M-F stock in 1908 and followed up by acquiring all the remainder from J.P. Morgan & Co. in 1910 and buying E-M-F's manufacturing plants at Walkerville, Ontario, Canada, and across the river in Detroit.[24] The former Ford Piquette Avenue Plant, located across Brush Street from the old E-M-F plant in the Milwaukee Junction area of Detroit, was purchased from Ford in January 1911 to become Studebaker Plant 10, used for assembly work until 1933.[23]

E-M-F was bought out by Studebaker, which formed Studebaker Canada. This was followed by rebadging E-M-F's products: the E-M-F as the Studebaker 30, the Flanders as the Studebaker 20[68] Sales of these rebadged models continued through the end of 1912.[68]

Elyria, Ohio (Studebaker-Garford)

[edit]400 Clark St, Elyria, OH

- Manufactured automobiles

Garford

[edit]

Under the agreement with Studebaker, Garford would receive completed chassis and drivetrains from Ohio and then mate them with Studebaker-built bodies, which were sold under the Studebaker-Garford brand name at premium prices. Prices listed for the Model G were $3,700 to $5,000 based on the body style used, equal to ($125,471 in 2023 dollars[15]) to ($169,556 in 2023 dollars [15]).[69] Eventually, vehicles with Garford-built engines began to carry the Studebaker name. Garford also built cars under its own name, and by 1907, attempted to increase production at the expense of Studebaker. Once the Studebakers discovered this, John Mohler Studebaker enforced a primacy clause, forcing Garford back on to the scheduled production quotas. The decision to drop the Garford name was made and the final product rolled off the assembly line by 1911, leaving Garford alone until it was acquired by John North Willys in 1913.

Vernon, California

[edit]

4530 Loma Vista Ave, Vernon, CA

- Manufactured automobiles

In 1938, the company built an assembly location at 4530 Loma Vista Avenue in Vernon, California, which remained in production until 1956. At one time, the facility was averaging 65 cars a day assembled from knock-down kits shipped by rail from the factory in South Bend, Indiana.[70] The factory manufactured the Champion, the Land Cruiser, and the Starlight. During the war, the factory was in close proximity to Douglas Aircraft and Lockheed Aircraft and built engine assemblies and nacelles for B-17s and PV-2 Harpoons.[27]

Hamilton, Ontario, Canada

[edit]391 Victoria Ave N, Hamilton, ON L8L 5G7

- Manufactured automobiles

On August 18, 1948, surrounded by more than 400 employees and a battery of reporters, the first vehicle, a blue Champion four-door sedan, rolled off of the Studebaker assembly line in Hamilton, Ontario.[41] The company was located in the former Otis-Fenson military weapons factory off Burlington Street on Victoria Avenue North, which was built in 1941. Having previously operated its British Empire export assembly plant at Walkerville, Ontario, Studebaker settled on Hamilton as a postwar Canadian manufacturing site because of the city's proximity to the Canadian steel industry.[citation needed]

Studebaker manufactured cars in Hamilton from 1948 to 1966.[68] After the South Bend plant shut, Hamilton was Studebaker's sole factory.[68] Studebaker briefly manufactured cars in Windsor, Ontario, from 1912 to 1936.

Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

[edit]Studebakers were assembled in Melbourne in right-hand drive configuration from CKD kits manufactured at Hamilton, Ontario, Canada beginning in 1960. The first location was the Canada Cycle and Car Company in the neighborhood of Tottenham, which assembled Studebaker Lark sedans and station wagons, the Studebaker Champ pickup truck and the Studebaker Silver Hawk. In 1964, after the South Bend, Indiana factory closed, Australian assembly was handed off to Continental & General's factory in West Heidelberg until 1968 when the last car was built. When the factory ceased operations Renault products were brought in to replace them. Previously, Studebakers were exported to Australia fully assembled beginning in 1948 in limited numbers.[71][72]

Studebaker had a long history of selling products in Australia, starting in the 1880s when horse-drawn wagons and carts were imported from the South Bend, Indiana factory, and as the company transitioned to automobiles, they were also brought in.[73]

Legacy

[edit]Due to the success that the Studebaker US6 proved in the Soviet Union, based on its design, mechanical parts, and technology, GAZ developed the GAZ-51 and GAZ-63 truck types, both of which outlived the US6 and the Studebaker company itself, being produced until the 1970s and were much more successful than the US6 truck was.[74]

The designers of the 1993 Dodge Ram stated that the Studebaker E series pickup was their main inspiration for the design.[75]

Spectra Merchandising International, Inc. produces a number of "retro" styled audio equipment under the brand name "Studebaker."[76]

Products

[edit]

Studebaker automobile models

[edit]- Studebaker Electric (1902–1912)

- Studebaker-Garford (1904–1911)

- Studebaker Six monobloc-engine models (1911–1918)

- Studebaker Light Four (1918–1920)

- Studebaker Big Six (1918–1927)

- Studebaker Special Six (1918–1927)

- Studebaker Light Six (includes Standard Six model) (1918–1927)

- Studebaker Commander (1927–1935, 1937–1958, 1964–1966)

- Studebaker President (1928–1942, 1955–1958)

- Studebaker Dictator/Director (1927–1937)

- Studebaker Champion (1939–1958)

- Studebaker Land Cruiser (1934–1954)

- Studebaker Conestoga (1954–1955)

- Studebaker Speedster (1955)

- Studebaker Scotsman (1957–1958)

- Hawk series:

- Studebaker Golden Hawk (1956–1958)

- Studebaker Silver Hawk (1957–1959)

- Studebaker Sky Hawk (1956)

- Studebaker Flight Hawk (1956)

- Studebaker Power Hawk (1956)

- Studebaker Hawk (1960–1961)

- Studebaker Gran Turismo Hawk (1962–1964)

- Studebaker Lark (1959–1966) (Includes the Lark-based 1964–66 Cruiser, Daytona, Commander, and Challenger)

- Studebaker Avanti (1962–1964)

- Studebaker Wagonaire (1963–1966)

Studebaker trucks

[edit]- Studebaker GN series (1929–1930)

- Studebaker S series (1930–1934)

- Studebaker T series (1934–1936)

- Studebaker W series (1934–1936)

- Studebaker J series (1937)

- Studebaker Coupe Express (1937–1939)

- Studebaker K series (1938–1940)

- Studebaker M series (1941–1942, 1945, 1946–1948)

- Studebaker US6 (1941–1945)

- Studebaker M29 Weasel (1942–1945)

- Studebaker 2R Series (1949–1953)

- Studebaker 3R Series (1954)

- Studebaker E series (1955–1964)

- Studebaker Transtar (1956–1958, 1960–1964)

- Studebaker Champ (1960–1964)

- Studebaker Zip Van (1964)

- M35 2-1/2 ton cargo truck (1950s through 1964)

Studebaker body styles

[edit]- Studebaker Starlight (1947–1955, 1958)

- Studebaker Starliner

- Coupe Express

Affiliated automobile marques

[edit]- Tincher: An early independent builder of luxury cars financed by Studebaker investment, 1903–1909

- Studebaker-Garford: Studebaker-bodied cars, 1904–1911

- E-M-F: Independent auto manufacturer that marketed cars through Studebaker wagon dealers, 1909–1912

- Erskine: Brand of automobile produced by Studebaker, 1926–1930

- Pierce-Arrow: owned by Studebaker 1928–1934[68]

- Rockne: Brand of automobile produced by Studebaker, 1932–1933

- Packard: 1954 merger partner of Studebaker

- Mercedes-Benz: Distributed through Studebaker dealers, 1958–1966

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "Out of the Inkwell Films, Incorporated". Progressive Silent Film List. Silent Era. Archived from the original on January 21, 2022. Retrieved January 21, 2022.

- ^ "Inkwell". Fleischer Studios. Archived from the original on January 21, 2022. Retrieved January 21, 2022.

- ^ "1600 broadway". bixography. Archived from the original on January 21, 2022. Retrieved January 21, 2022.

- ^ "1600 Broadway on The Square". Condopedia. Archived from the original on April 4, 2023. Retrieved January 21, 2022.

- ^ "German heritage biography: Studebaker Brothers". Archived from the original on October 17, 2006. Retrieved February 6, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Hendry, Maurice M (1972). Studebaker: One can do a lot of remembering in South Bend. New Albany, Indiana: Automobile Quarterly. pp. 228–75. Vol X, 3rd Q, 1972.

- ^ E.g., see motoring review "An ideal car Archived October 21, 2020, at the Wayback Machine" in The Brisbane Courier, April 25, 1928, p.8

- ^ a b "South Bend builds last Studebaker". Spokesman-Review. (Spokane, Washington). Associated Press. December 21, 1963. p. 15.

- ^ "Studebaker Corporation And Wagner Electric". The New York Times. December 17, 1966. Archived from the original on March 3, 2022. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

- ^ "Worthington Completes Merger With Studebaker". The New York Times. November 28, 1967. Archived from the original on March 4, 2022. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

- ^ "A brief history of Studebaker, 1852–1966". Hemmings. Archived from the original on December 1, 2022. Retrieved December 1, 2022.

- ^ Genealogy at Conway's of Ireland Archived October 5, 2011, at the Wayback Machine—John Clement Studebaker

- ^ a b c d e f g h Erskine, Albert Russel (1918). History of the Studebaker corporation. Retrieved February 7, 2016.

- ^ "Exhibits are evidence of the historical significance of Peter Studebaker Archived August 16, 2017, at the Wayback Machine"

- ^ a b c d e f g h i 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Longstreet, Stephen (1952). A Century on Wheels: The Story of Studebaker. New York: Henry Holt and Company. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-8371-3978-4. 1st edn., 1952.

- ^ Petrol Motor Vehicles on Railways Bunbury Herald, Western Australia, May 3, 1919, at Trove

- ^ Clymer, Floyd. Treasury of Early American Automobiles, 1877–1925 (New York: Bonanza Books, 1950), p. 178.

- ^ Magazines, Hearst (October 7, 1930). "Popular Mechanics". Hearst Magazines. Archived from the original on June 3, 2023. Retrieved March 11, 2023 – via Google Books.

- ^ Strohl, Daniel. "Studebaker's tree sign to be restored for 75th anniversary". Hemmings Daily. Hemmings Motor News. Archived from the original on August 3, 2013. Retrieved July 31, 2013.

- ^ "Discuss Detroit: Old Car Factories – 6". Discuss Detroit: Old car Factories. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved February 25, 2021.

- ^ "What Makes Detroit A Great City? "Industry and Henry Ford"". Detroit Historical Society. Archived from the original on March 3, 2022. Retrieved February 25, 2021.

- ^ a b "National Historic Landmark Nomination – Ford Piquette Avenue Plant, pp. 22–23" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on February 22, 2017. Retrieved November 20, 2015.

- ^ a b "Studebaker Factory Supports 500 Families Living in Border Area". Financial Post. Western Libraries (Ontario). October 31, 1929. Archived from the original on July 25, 2011. Retrieved June 9, 2011.

- ^ Peck, Merton J. & Scherer, Frederic M. The Weapons Acquisition Process: An Economic Analysis (1962) Harvard Business School p. 619

- ^ Herman, Arthur (2012). Freedom's Forge: How American Business Produced Victory in World War II, pp. 81, 215–18, 312, Random House, New York. ISBN 978-1-4000-6964-4.

- ^ a b "Studebaker Pacific Corporation". usautoindustryworldwartwo.com. Archived from the original on November 26, 2019. Retrieved December 2, 2019.

- ^ a b Virgil M. Exner’s Striking Studebaker Starlight Coupe Design Archived November 19, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. The Old Motor, September 26, 2016. Accessed November 19, 2016

- ^ Studebaker Champion Starlight coupe Archived August 26, 2011, at the Wayback Machine in America on the Move history website

- ^ Dallas Morning News, August 9, 1956, Part 3, p. 5.

- ^ The Washington Post and Times-Herald, January 6, 1960, p. 21.

- ^ "The President & the Picket". Time. January 26, 1962. Archived from the original on May 10, 2008. Retrieved June 9, 2011.

- ^ Studebaker-Packard Corporation Annual Report, 1961, p. 4.

- ^ Aberdeen Daily News, February 8, 1962, p. 7.

- ^ Plain Dealer, May 18, 1962, p. 25

- ^ "Studebaker says U.S. closings due". Spokane Daily Chronicle. (Washington). Associated Press. December 9, 1963. p. 18.

- ^ "U.S. plant plans last Studebaker". Spokane Daily Chronicle. (Washington). Associated Press. December 20, 1963. p. 18.

- ^ "A look at Studebaker's last trucks, 1960-'64". Hemmings. Pat Foster. Archived from the original on June 11, 2023. Retrieved June 11, 2023.

- ^ "Negroes Lose 1,500 Posts in South Bend". Pittsburgh Courier. December 21, 1963.

- ^ Johnson, Dale (March 4, 2006). "The last days of Studebaker". The Toronto Star. Archived from the original on March 15, 2007. Retrieved February 6, 2007 – via Hemmings.com.

- ^ a b c "The Hamilton Memory Project: Studebaker" (Press release). The Hamilton Spectator – Souvenir Edition. June 10, 2006. p. MP45.

- ^ Gloor, Roger (March 13, 1969). Braunschweig, Robert; et al. (eds.). "Die Personenwagen-Weltproduktion 1968/La production mondiale de voitures en 1968" [The world's car production 1968]. Automobil Revue – Katalognummer 1969/Revue Automobile – Numéro catalogue 1969 (in German and French). 64. Berne, Switzerland: Hallwag AG: 526.

- ^ Arlt, Glenn (December 27, 2015). "The Link Between Studebaker and Nissan – Revealed!". Archived from the original on December 27, 2016. Retrieved December 26, 2016.

- ^ Turnbull, Alex (October 26, 2005). "Arboreal typography". Google Sightseeing. Archived from the original on May 2, 2010. Retrieved June 9, 2011.

- ^ a b c Brochure: South Bend's Titans of Industry Archived May 22, 2013, at the Wayback Machine (2012) at St Joseph County Indiana. Accessed April 12, 2013

- ^ Bosch Complete Plant Closure (Auction) Archived January 7, 2012, at the Wayback Machine at Britton Management Group, November 2011

- ^ Ferreira, Colleen Bosch plant to close in South Bend at wsbt.com news, November 16, 2010 Archived July 23, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ History of the New Carlisle Test Facility at Bosch US website

- ^ Wagner Electric, Studebaker Vote To Merger Firms Archived March 3, 2022, at the Wayback Machine Toledo Blade May 10, 1967, p 70. At Google News, accessed March 24, 2013

- ^ Worthington to merge Railway Age July 31, 1967 page 64

- ^ Studebaker, Worthington Vote Merger Despite Antitrust Archived March 3, 2022, at the Wayback Machine Montreal Gazette February 16, 1968, p. 14. At Google News, accessed March 24, 2013

- ^ White company history Archived September 29, 2007, at the Wayback Machine at fundinguniverse.com

- ^ The U.S. Air Force project designation MX-232 was allocated to the proposed 5000-hp engine, according to researchers George Cully & Andreas Parsch. See explanation and link Archived July 25, 2010, at the Wayback Machine from Designations Of U.S. Air Force Projects Archived June 16, 2016, at the Wayback Machine (2005)

- ^ Holderith, Peter (May 27, 2020). "The 2003 Studebaker XUV Attempted to Revive a Classic Name with an Illegal Hummer Clone". The Drive. Retrieved December 17, 2024.

- ^ Dowling, Neil (February 22, 2012). "Studebaker revival bid as hybrid - Car News". CarsGuide. Retrieved December 17, 2024.

- ^ Beissmann, Tim (February 6, 2012). "Studebaker planning a comeback". Drive. Retrieved December 17, 2024.

- ^ Gastelu, Gary (February 17, 2012). "Colorado man plots return of Studebaker". Fox News. Retrieved December 17, 2024.

- ^ a b "Studebaker South Bend Plant Photos". The American Automobile Industry in World War Two. Archived from the original on June 10, 2021. Retrieved March 3, 2021.

- ^ Register Archived June 4, 2011, at the Wayback Machine California Historic Landmark Project Collection 1936–1940

- ^ Guttman, Jon. "Studebaker Wagon". Military History (July 2013). WHG: 23.

- ^ See building No.3 on illustration Looking West from Michigan Boulevard Archived January 14, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The Presidential Carriage Collection Archived August 29, 2016, at the Wayback Machine at Studebaker National Museum. Accessed February 7, 2016

- ^ "Clydesdales". Archived from the original on May 9, 2009. Retrieved February 2, 2013.

- ^ "John Mohler Studebaker". Automotive Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved March 4, 2016.

- ^ "Ex-State Senator Frederick S. Fish will leave Newark to become the general counsel of the Studebaker Brothers' Manufacturing Company at South Bend, Ind." NYT City & Suburban News Archived February 10, 2022, at the Wayback Machine, March 26, 1891 (PDF)

- ^ "Connecting the Windy City- Studebaker Engine Plant Up for Sale". August 9, 2019. Archived from the original on June 27, 2022. Retrieved August 1, 2022.

- ^ Yanik, Anthony J. (2001). The E-M-F Company. SAE. ISBN 0-7680-0716-X.

- ^ a b c d e Windsor Public Library online(retrieved June 13, 2017) Archived September 19, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Copy of Advertisement from "Cosmopolitan Magazine" unknown date". Myn Transport Blog. Archived from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved February 11, 2021.

- ^ "L.A.T.E: Who Knew #8 L.A.'s Booming Auto Industry a Thing of the Past". January 13, 2015. Archived from the original on January 13, 2015.

- ^ "Australian Motor Vehicle Manufacture". All about Australia. Australia For Everyone. Archived from the original on February 28, 2021. Retrieved March 3, 2021.

- ^ "Item MM 137690 Negative – Canada Cycle & Motor Company, Pair with Motor Car Brochure, Victoria, 15 Feb 1960". Museum Victoria Collections. Museums Victoria. Archived from the original on August 8, 2020. Retrieved March 3, 2021.

- ^ "Studebaker in Australia". The Studebaker Car Club of Australia. Studebaker car club. Archived from the original on March 3, 2021. Retrieved March 3, 2021.

- ^ "ГАЗ-51". Denisovets. Retrieved December 23, 2024.

- ^ "U.S. Patent D396,828 – Body Styling of 1994 Dodge Ram". United States Patent and Trademark Office. August 11, 1998. Archived from the original on February 24, 2021. Retrieved November 22, 2010.

- ^ https://spectraintl.com/index.php/brands/studebaker Archived June 10, 2021, at the Wayback Machine Spectra Merchandising International: Studebaker products (Retrieved: 10 June 2021)

References

[edit]- Bonsall, Thomas E More Than They Promised: The Studebaker Story Stanford University Press (2000)

- Erskine, A R History of the Studebaker Corporation, South Bend (1918) (via – Google Books)

- Foster, Patrick Studebaker: America's Most Successful Independent Automaker Motorbooks

- Grist, Peter Virgil Exner: Visioneer: The official biography of Virgil M. Exner, designer extraordinaire Veloce, US

- Longstreet, Stephen A Century on Wheels: The Story of Studebaker, A History, 1852–1952, New York: Henry Holt and Co (1952)

Further reading

[edit]- Bodnar, John. "Power and memory in oral history: Workers and managers at Studebaker." Journal of American History 75.4 (1989): 1201–1221. JSTOR 1908636.

- Clement Studebaker House, Tippecanoe Place National Register of Historic Places Inventory – Nomination Form. (The heritage research includes details of the early history of the firm at South Bend.)

- Severson A. Lark and Super Lark: The Last Days of Studebaker at Ate Up With Motor October 17, 2009

- Justice L. The Studebaker Company: A Journey from Wagons to Wheels at "Classic Cars Online US" December 1, 2023

External links

[edit]- Collection of mid-twentieth-century advertising featuring Studebaker automobiles Archived October 24, 2020, at the Wayback Machine from The TJS Labs Gallery of Graphic Design.

- 1963 model range at RitzSite

- The Studebaker Drivers Club

- Studebaker

- 1852 establishments in Indiana

- 1900s cars

- 1910s cars

- 1920s cars

- 1930s cars

- 1940s cars

- 1950s cars

- 1960s cars

- American companies disestablished in 1968

- American companies established in 1852

- Brass Era vehicles

- Car brands

- Coachbuilders of the United States

- Companies based in St. Joseph County, Indiana

- Defunct brands

- Defunct companies based in Indiana

- Defunct motor vehicle manufacturers of the United States

- Former components of the Dow Jones Industrial Average

- History of Hamilton, Ontario

- Motor vehicle manufacturers based in Indiana

- South Bend, Indiana

- Truck manufacturers of the United States

- Vehicle manufacturing companies disestablished in 1968

- Vehicle manufacturing companies established in 1852

- Vintage vehicles