The Spirit of the Age

This article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. (June 2023) |

Title page of The Spirit of the Age 2nd London edition | |

| Author | William Hazlitt |

|---|---|

| Genre | Social criticism biography |

| Published | 11 January 1825 (Henry Colburn) |

| Publication place | England |

| Media type | |

| Preceded by | Liber Amoris: Or, The New Pygmalion |

| Followed by | The Plain Speaker: Opinions on Books, Men, and Things |

| Text | The Spirit of the Age: Or, Contemporary Portraits at Wikisource |

The Spirit of the Age (full title The Spirit of the Age: Or, Contemporary Portraits) is a collection of character sketches by the early 19th century English essayist, literary critic, and social commentator William Hazlitt, portraying 25 men, mostly British, whom he believed to represent significant trends in the thought, literature, and politics of his time. The subjects include thinkers, social reformers, politicians, poets, essayists, and novelists, many of whom Hazlitt was personally acquainted with or had encountered. Originally appearing in English periodicals, mostly The New Monthly Magazine in 1824, the essays were collected with several others written for the purpose and published in book form in 1825.

The Spirit of the Age was one of Hazlitt's most successful books.[1] It is frequently judged to be his masterpiece,[2] even "the crowning ornament of Hazlitt's career, and ... one of the lasting glories of nineteenth-century criticism."[3] Hazlitt was also a painter and an art critic, yet no artists number among the subjects of these essays. His artistic and critical sensibility, however, infused his prose style—Hazlitt was later judged to be one of the greatest of English prose stylists as well[4]—enabling his appreciation of portrait painting to help him bring his subjects to life.[5] His experience as a literary, political, and social critic contributed to Hazlitt's solid understanding of his subjects' achievements, and his judgements of his contemporaries were later often deemed to have held good after nearly two centuries.[6]

The Spirit of the Age, despite its essays' uneven quality, has been generally agreed to provide "a vivid panorama of the age".[7] Yet, missing an introductory or concluding chapter, and with few explicit references to any themes, it was for long also judged as lacking in coherence and hastily thrown together.[8] More recently, critics have found in it a unity of design, with the themes emerging gradually, by implication, in the course of the essays and even supported by their grouping and presentation.[9] Hazlitt also incorporated into the essays a vivid, detailed and personal, "in the moment" kind of portraiture that amounted to a new literary form and significantly anticipated modern journalism.[10]

Background

[edit]Preparation

[edit]Hazlitt was well prepared to write The Spirit of the Age. Hackney College, where he studied for two years, was known for fostering radical ideas,[11] immersing him in the spirit of the previous age, and a generation later helping him understand changes he had observed in British society.[12] He was befriended in his early years by the poets Wordsworth and Coleridge,[13] who at that time shared his radical thinking, and soon he entered the circle of reformist philosopher William Godwin.[14] His brother John was also responsible for helping him connect with other like-minded souls,[15] leading him to the centre of London intellectual culture, where he met others who, years later, along with Wordsworth, Coleridge, and Godwin, would be brought to life in this book, particularly Charles Lamb[16] and, some time afterward, Leigh Hunt.[17]

Although Hazlitt had aimed at a career in philosophy, he was unable to make a living by it.[15] His studies and extensive thinking about the problems of the day, however, provided a basis for judging contemporary thinkers. (He had already begun, before he was thirty, with an extensive critique of Malthus's theory of population.)[18] After having practised for a while as an artist[19] (a major part of his background that entered into the making of this book not in the selection of its content but as it helped inform his critical sensibility and his writing style),[20] he found work as a political reporter, which exposed him to the major politicians and issues of the day.[21]

Hazlitt followed this by many years as a literary, art, and theatre critic, at which he enjoyed some success.[22] He was subsequently beset by numerous personal problems, including a failed marriage, illness,[23] insolvency,[24] a disastrous love entanglement that led to a mental breakdown,[25] and scurrilous attacks by political conservatives, many of them fuelled by his indiscreet publication of Liber Amoris, a thinly disguised autobiographical account of his love affair.[26] English society was becoming increasingly prudish,[27] the ensuing scandal effectively destroyed his reputation, and he found it harder than ever to earn a living.[28] He married a second time. Consequently, more than ever in need of money,[29] he was forced to churn out article after article for the periodical press.

"The Spirits of the Age"

[edit]Hazlitt had always been adept at writing character sketches.[30] His first was incorporated into Free Thoughts on Public Affairs, written in 1806, when he was scarcely 28 years old.[31] Pleased with this effort, he reprinted it three times as "Character of the Late Mr. Pitt", in The Eloquence of the British Senate (1807), in The Round Table (1817), and finally in Political Essays (1819).[32]

Another favourite of his own was "Character of Mr. Cobbett", which first appeared in Table-Talk in 1821 and was later incorporated into The Spirit of the Age. Following this proclivity, toward the end of 1823 Hazlitt developed the idea of writing "a series of 'characters' of men who were typical of the age".[30] The first of these articles appeared in the January 1824 issue of The New Monthly Magazine, under the series title "The Spirits of the Age".[30]

Publication

[edit]

Four more articles appeared in the series, and then Hazlitt prepared numerous others with the goal of collecting them into a book. After he had left England for a tour of the continent with his wife, that book, bearing the title The Spirit of the Age: Or Contemporary Portraits, was published in London on 11 January 1825,[33] by Henry Colburn, and printed by S. and R. Bentley. In Paris, Hazlitt arranged to have an edition, with a somewhat different selection and ordering of articles, published there by A. & W. Galignani. Unlike either English edition, this one bore his name on the title page. Finally, later in the same year, Colburn brought out the second English edition, with contents slightly augmented, revised, and rearranged but in many respects similar to the first edition. No further editions would appear in Hazlitt's lifetime.[34]

Editions

[edit]Four of the essays that made it into the first edition of The Spirit of the Age, plus part of another, had appeared, without authorial attribution, in the series "The Spirits of the Age", in the following order: "Jeremy Bentham", "Rev. Mr. Irving", "The Late Mr. Horne Tooke", "Sir Walter Scott", and "Lord Eldon", in The New Monthly Magazine for 1824 in the January, February, March, April, and July issues, respectively.[35]

In the book first published in January 1825, these essays, with much additional material, appeared as follows: "Jeremy Bentham", "William Godwin", "Mr. Coleridge", "Rev. Mr. Irving", "The Late Mr. Horne Tooke", "Sir Walter Scott", "Lord Byron", "Mr. Campbell—Mr. Crabbe", "Sir James Mackintosh", "Mr. Wordsworth", "Mr. Malthus", "Mr. Gifford", "Mr. Jeffrey", "Mr. Brougham—Sir F. Burdett", "Lord Eldon—Mr. Wilberforce", "Mr. Southey", "Mr. T. Moore—Mr. Leigh Hunt", and "Elia—Geoffrey Crayon". An untitled section characterising James Sheridan Knowles concludes the book.[34] A portion of "Mr. Campbell—Mr. Crabbe" was adapted from an essay Hazlitt contributed (on Crabbe alone) to the series "Living Authors" in The London Magazine, "No. V" in the May 1821 issue.[36]

Despite the closeness in the ordering of the contents of the first and second English editions, there are numerous differences between them, and even more between them and the Paris edition that appeared in between. The Paris edition, the only one to credit Hazlitt as the author, omitted some material and added some. The essays (in order) were as follows: "Lord Byron", "Sir Walter Scott", "Mr. Coleridge", "Mr. Southey", "Mr. Wordsworth", "Mr. Campbell and Mr. Crabbe" (the portion on Campbell was here claimed by Hazlitt to be "by a friend", though he wrote it himself),[36] "Jeremy Bentham", "William Godwin", "Rev. Mr. Irving", "The Late Mr. Horne Tooke", "Sir James Mackintosh", "Mr. Malthus", "Mr. Gifford", "Mr. Jeffrey", "Mr. Brougham—Sir F. Burdett", "Lord Eldon and Mr. Wilberforce", "Mr. Canning" (brought in from the 11 July 1824 issue of The Examiner, where it bore the title "Character of Mr. Canning", this essay appeared only in the Paris edition),[37] "Mr. Cobbett" (which had first appeared in Hazlitt's book Table-Talk in 1821),[34] and "Elia". This time the book concludes with two untitled sections, the first on "Mr. Leigh Hunt" (as shown in the page header), the second again on Knowles, with the page header reading "Mr. Knowles".[38]

Finally, later in 1825, the second English edition was brought out (again, anonymously). There, the essays were "Jeremy Bentham", "William Godwin", "Mr. Coleridge", "Rev. Mr. Irving", "The Late Mr. Horne Tooke", "Sir Walter Scott", "Lord Byron", "Mr. Southey", "Mr. Wordsworth", "Sir James Mackintosh", "Mr. Malthus", "Mr. Gifford", "Mr. Jeffrey", "Mr. Brougham—Sir F. Burdett", "Lord Eldon—Mr. Wilberforce", "Mr. Cobbett", "Mr. Campbell and Mr. Crabbe", "Mr. T. Moore—Mr. Leigh Hunt", and "Elia, and Geoffrey Crayon". Again, an account of Knowles completes the book.[34]

Essays

[edit]The order of the following accounts of the essays in the book follows that of the second English edition. (The essay on George Canning, however, appeared only in the Paris edition.)

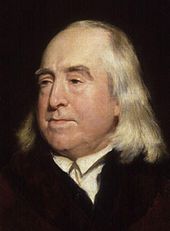

Jeremy Bentham

[edit]Jeremy Bentham (1748–1832) was an English philosopher, jurist, and social and legislative reformer. He was a major proponent of Utilitarianism, based on the idea of "the greatest happiness of the greatest number", which he was the first to systematise, introducing it as the "principle of utility".[39] Hazlitt's link with Bentham was unusual, as Bentham was his landlord and lived close by.[40] Bentham would sometimes take his exercise in his garden, which was visible from Hazlitt's window. The two were not personally acquainted,[41] yet what Hazlitt observed enabled him to interweave personal observations into his account of the older man.[42]

Bentham was a representative of the reformist element of the time. Yet, also symptomatic of "the spirit of the age"—and the note Hazlitt strikes on the opening of his sketch—was the fact that Bentham had only a small following in England, yet enjoyed respectful celebrity in nations half a world away. "The people of Westminster, where he lives, hardly dream of such a person ...."[43] "His name is little known in England, better in Europe, best of all in the plains of Chili and the mines of Mexico."[43]

Hazlitt notes Bentham's persistent unity of purpose, "intent only on his grand scheme of Utility .... [r]egarding the people about him no more than the flies of a summer. He meditates the coming age .... he is a beneficent spirit, prying into the universe ...."[44]

But Hazlitt soon qualifies his admiring tone. First, he cautions against mistaking Bentham for the originator of the theory of utility; rather, "his merit is, that he has brought all the objections and arguments, more distinctly labelled and ticketed, under this one head, and made a more constant and explicit reference to it at every step of his progress, than any other writer."[45]

As Bentham's thinking gained complexity, his style, unfortunately, deteriorated. "It is a barbarous philosophical jargon" even though it "has a great deal of acuteness and meaning in it, which you would be glad to pick out if you could. ... His works have been translated into French", quips Hazlitt. "They ought to be translated into English."[46]

"His works have been translated into French.

They ought to be translated into English."

Bentham's refined and elaborated logic fails, in Hazlitt's assessment, to take into account the complexities of human nature.[47] In his attempt to reform mankind by reasoning, "he has not allowed for the wind ". Man is far from entirely "a logical animal", Hazlitt argues.[45] Bentham bases his efforts to reform criminals on the fact that "'all men act from calculation'". Yet, Hazlitt observes, "it is of the very essence of crime to disregard consequences both to ourselves and others."[48]

Hazlitt proceeds to contrast in greater detail the realities of human nature with Bentham's benevolent attempts to manipulate it. Bentham would observe and attempt to alter the behaviour of a criminal by placing him in a "Panopticon, that is, a sort of circular prison, with open cells, like a glass bee-hive."[49] When the offender is freed from its restraints, however, Hazlitt questions whether it is at all likely he will maintain the altered behaviour that had seemed so amenable to change. "Will the convert to the great principle of Utility work when he was from under Mr. Bentham's eye, because he was forced to work when under it? ... Will he not steal, now that his hands are untied? ... The charm of criminal life ... consists in liberty, in hardship, in danger, and in the contempt of death, in one word, in extraordinary excitement".[49]

Further, there is a flaw in Bentham's endlessly elaborating on his single idea of utility. His "method of reasoning" is "comprehensive ..." but it "includes every thing alike. It is rather like an inventory, than a valuation of different arguments."[50] Effective argument needs more colouring. "By aiming at too much ... it loses its elasticity and vigour".[51] Hazlitt also objects to Bentham's considering "every pleasure" as "equally a good".[45] This is not so, "for all pleasure does not equally bear reflecting on." Even if we take Bentham's reasoning as presenting "the whole truth", human nature is incapable of acting solely upon such grounds, "needing helps and stages in its progress" to "bring it into a tolerable harmony with the universe."[51]

In the manner of later journalists[52] Hazlitt weaves into his criticism of the philosopher's ideas an account of Bentham the man. True to his principles, "Mr. Bentham, in private life, is an amiable and exemplary character", of regular habits, and with childlike characteristics, despite his advanced age. In appearance, he is like a cross between Charles Fox and Benjamin Franklin,[42] "a singular mixture of boyish simplicity and the venerableness of age."[53] He has no taste for poetry, but relaxes by playing the organ. "He turns wooden utensils in a lathe for exercise, and fancies he can turn men in the same manner."[54]

A century and a half later, critic Roy Park acclaimed "Hazlitt's criticism of Bentham and Utilitarianism" here and in other essays as constituting "the first sustained critique of dogmatic Utilitarianism."[55]

William Godwin

[edit]William Godwin (1756–1836) was an English philosopher, social reformer, novelist, and miscellaneous writer. After the French Revolution had given fresh urgency to the question of the rights of man, in 1793, in response to other books written in reaction to the upheaval, and building on ideas developed by 18th-century European philosophers,[56] Godwin published An Enquiry Concerning Political Justice. There he espoused (in the words of historian Crane Brinton) "the natural goodness of man, the corruptness of governments and laws, and the consequent right of the individual to obey his inner voice against all external dictates."[57]

Godwin immediately became an inspiration to Hazlitt's generation.[12] Hazlitt had known Godwin earlier, their families having been friends since before Hazlitt's birth; as he also often visited the elder man in London in later years, he was able to gather impressions over many decades.[12] While so many of his contemporaries soon abandoned Godwin's philosophy, Hazlitt never did so completely; yet he had never quite been a disciple either.[58] Eventually, although he retained respect for the man, he developed a critical distance from Godwinian philosophy.[59]

By the time Hazlitt wrote this sketch some thirty years after Godwin's glory years, the political climate had changed drastically, owing in large part to the British government's attempts to repress all thinking they deemed dangerous to the public peace.[60] Consequently, Godwin, though he had never been an advocate of reform by violent means,[61] had disappeared almost completely from the public eye. Hazlitt, at the start of his essay, focuses on this drastic change.

At the turn of the 19th century, notes Hazlitt, Godwin had been hailed as the philosopher who expounded "liberty, truth, justice".[54] His masterwork, An Enquiry Concerning Political Justice, "gave ... a blow to the philosophical mind of the country". To those with a penchant for thinking about the human condition, Godwin was "the very God of our idolatry" who "carried with him all the most sanguine and fearless understandings of the time" and engaged the energy of a horde of "young men of talent, of education, and of principle."[62] These included some of Hazlitt's most famous former friends, the poets Wordsworth, Coleridge, and Southey.[63]

Twenty-five years later, Hazlitt looks back in astonishment that, in the interval, Godwin's reputation "has sunk below the horizon, and enjoys the serene twilight of a doubtful immortality."[64] "The Spirit of the Age", he declares in the opening sentence, "was never more fully shown than in its treatment of this writer—its love of paradox and change, its dastard submission to prejudice and to the fashion of the day."[54]

Yet there are problems with Godwin's philosophy, Hazlitt concedes. "The author of the Political Justice took abstract reason for the rule of conduct, and abstract good for its end. He absolves man from the gross and narrow ties of sense, custom, authority, private and local attachment, in order that he may devote himself to the boundless pursuit of universal benevolence."[65] In its rules for determining the recipients of this benevolence, Godwin's philosophy goes further than Christianity in completely removing from consideration personal ties or anything but "the abstract merits, the pure and unbiassed justice of the case."[66]

In practice, human nature can rarely live up to this exalted standard. "Every man ... was to be a Regulus, a Codrus, a Cato, or a Brutus—every woman a Mother of the Gracchi. ... But heroes on paper might degenerate into vagabonds in practice, Corinnas into courtezans."[67] Hazlitt proceeds with several examples:

... a refined and permanent individual attachment is intended to supply the place and avoid the inconveniences of marriage; but vows of eternal constancy, without church security, are found to be fragile. ... The political as well as the religious fanatic appeals from the overweening opinion and claims of others to the highest and most impartial tribunal, namely, his own breast. ... A modest assurance was not the least indispensable virtue in the new perfectibility code; and it was hence discovered to be a scheme, like other schemes where there are all prizes and no blanks, for the accommodation of the enterprizing and cunning, at the expense of the credulous and honest. This broke up the system, and left no good odour behind it![67]

Yet the social failure of this attempt to guide our conduct by pure reason alone is no ground for discrediting reason itself. On the contrary, Hazlitt argues passionately, reason is the glue that binds civilisation together. And if reason can no longer be considered as "the sole and self-sufficient ground of morals",[68] we must thank Godwin for having shown us why, by having "taken this principle, and followed it into its remotest consequences with more keenness of eye and steadiness of hand than any other expounder of ethics."[68] By doing so, he has revealed "the weak sides and imperfections of human reason as the sole law of human action."[68]

"The Spirit of the Age was never more fully shown than in its treatment of this writer—its love of paradox and change, its dastard submission to prejudice and to the fashion of the day."

Hazlitt moves on to Godwin's accomplishments as a novelist. For over a century, many critics took the best of his novels, Caleb Williams, as a kind of propaganda novel, written to impress the ideas of Political Justice on the minds of the multitude who could not grasp its philosophy;[69] this was what Godwin himself had claimed in the book's preface. But Hazlitt was impressed by its strong literary qualities, and, to a lesser extent, those of St. Leon, exclaiming: "It is not merely that these novels are very well for a philosopher to have produced—they are admirable and complete in themselves, and would not lead you to suppose that the author, who is so entirely at home in human character and dramatic situation, had ever dabbled in logic or metaphysics."[70]

Next Hazlitt compares Godwin's literary method to Sir Walter Scott's in the "Waverley Novels". Hazlitt devoted considerable thought to Scott's novels over several years, somewhat modifying his views about them;[71] this is one of two discussions of them in this book, the other being in the essay on Scott. Here, it is Godwin's method that is seen as superior. Rather than, like Scott, creating novels out of "worm-eaten manuscripts ... forgotten chronicles, [or] fragments and snatches of old ballads",[72] Godwin "fills up his subject with the ardent workings of his own mind, with the teeming and audible pulses of his own heart."[72] On the other hand, the flaw in relying so intensively on one's own imagination is that one runs out of ideas. "He who draws upon his own resources, easily comes to an end of his wealth."[72]

Hazlitt then comments on Godwin's other writings and the nature of his genius. His productions are not spontaneous but rather rely on long, laboured thought. This quality also limits Godwin's powers of conversation, so he fails to appear the man of genius he is. "In common company, Mr. Godwin either goes to sleep himself, or sets others to sleep."[73] But Hazlitt closes his essay with personal recollections of the man (and, as with Bentham, a description of his appearance) that set him in a more positive light: "you perceive by your host's talk, as by the taste of seasoned wine, that he has a cellarage in his understanding."[73]

The scholar, critic, and intellectual historian Basil Willey, writing a century later, thought that Hazlitt's "essay on Godwin in The Spirit of the Age is still the fairest and most discerning summary I know of".[74]

Mr. Coleridge

[edit]Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772–1834) was a poet, philosopher, literary critic, and theologian who was a major force behind the Romantic movement in England. No single person had meant more to Hazlitt's development as a writer than Coleridge, who changed the course of Hazlitt's life on their meeting in 1798.[75] Afterwards at odds over politics, they became estranged, but Hazlitt continued to follow the intellectual development of one who answered more closely to his idea of a man of genius than anyone he had ever met,[76] as he continued to chastise Coleridge and other former friends for their abandonment of the radical ideals they had once shared.[77]

Unlike the accounts of Bentham and Godwin, Hazlitt's treatment of Coleridge in The Spirit of the Age presents no sketch of the man pursuing his daily life and habits. There is little about his appearance; the focus is primarily on the development of Coleridge's mind. Coleridge is a man of undoubted "genius", whose mind is "in the first class of general intellect".[78] His problem is that he has been too bewitched by the mass of learning and literature from antiquity to the present time to focus on creating any truly lasting literary or philosophical work of his own, with the exception of a few striking poems early in his career.

In an extensive account later acclaimed as brilliant,[79] even "a rhetorical summit of English prose",[80] Hazlitt surveys the astonishing range and development of Coleridge's studies and literary productions, from the poetry he wrote as a youth, to his deep and extensive knowledge of Greek dramatists, "epic poets ... philosophers ... [and] orators".[81] He notes Coleridge's profound and exhaustive exploration of more recent philosophy—including that of Hartley, Priestley, Berkeley, Leibniz, and Malebranche—and theologians such as Bishop Butler, John Huss, Socinus, Duns Scotus, Thomas Aquinas, Jeremy Taylor, and Swedenborg. He records Coleridge's fascination also with the poetry of Milton and Cowper, and the "wits of Charles the Second's days".[82] Coleridge, he goes on, also "dallied with the British Essayists and Novelists, ... and Johnson, and Goldsmith, and Junius, and Burke, and Godwin ... and ... Rousseau, and Voltaire".[82] And then, observes Hazlitt, Coleridge "lost himself in ... the Kantean philosophy, and ... Fichte and Schelling and Lessing".[83]

Having followed in its breadth and depth Coleridge's entire intellectual career, Hazlitt now pauses to ask, "What is become of all this mighty heap of hope, of thought, of learning, and humanity? It has ended in swallowing doses of oblivion and in writing paragraphs in the Courier.—Such, and so little is the mind of man!"[83]

Hazlitt treats Coleridge's failings more leniently here than he had in earlier accounts[84] (as he does others of that circle who had with him earlier "hailed the rising orb of liberty").[83] It is to be understood, he explains, that any man of intellect born in that age, with its awareness of so much that had already been accomplished, might feel incapable of adding anything to the general store of knowledge or art. Hazlitt characterises the age itself as one of "talkers, and not of doers. ... The accumulation of knowledge has been so great, that we are lost in wonder at the height it has reached, instead of attempting to climb or add to it; while the variety of objects distracts and dazzles the looker-on." And "Mr. Coleridge [is] the most impressive talker of his age ...".[85]

"What is become of all this mighty heap of hope, of thought, of learning, and humanity? It has ended in swallowing doses of oblivion and in writing paragraphs in the Courier.—Such, and so little is the mind of man!"

As for Coleridge's having gone over "to the unclean side"[83] in politics, however regrettable, it may be understood by looking at the power then held by government-sponsored critics of any who seemed to threaten the established order. "The flame of liberty, the light of intellect was to be extinguished with the sword—or with slander, whose edge is sharper than the sword."[86] Though Coleridge did not go as far as some of his colleagues in accepting a government office in exchange for withholding criticism of the current order, neither did he, in Hazlitt's account, align himself with such philosophers as Godwin, who, overtly steadfast in their principles, could be more resistant to "discomfiture, persecution, and disgrace."[86]

Following his typical method of explaining by antitheses,[87] Hazlitt contrasts Coleridge and Godwin. The latter, having far less general capacity, nevertheless was capable of fully utilising his talents by focusing intently on work he was capable of; while the former, "by dissipating his [mind], and dallying with every subject by turns, has done little or nothing to justify to the world or to posterity, the high opinion which all who have ever heard him converse, or known him intimately, with one accord entertain of him."[88]

Critic David Bromwich finds in what Hazlitt does portray of Coleridge the man—metaphorically depicting the state of his mind—as rich with allusions to earlier poets and "echoes" of Coleridge's own poetry:[89]

Mr. Coleridge has a "mind reflecting ages past": his voice is like the echo of the congregated roar of the 'dark rearward and abyss' of thought. He who has seen a mouldering tower by the side of a chrystal lake, hid by the mist, but glittering in the wave below, may conceive the dim, gleaming, uncertain intelligence of his eye; he who has marked the evening clouds uprolled (a world of vapours), has seen the picture of his mind, unearthly, unsubstantial, with gorgeous tints and ever-varying forms ...[90]

Rev. Mr. Irving

[edit]The Reverend Edward Irving (1792–1834) was a Scottish Presbyterian minister who, beginning in 1822, created a sensation in London with his fiery sermons denouncing the manners, practices, and beliefs of the time. His sermons at the Caledonian Asylum Chapel were attended by crowds that included the rich, the powerful, and the fashionable.[91] Hazlitt was present on at least one occasion, 22 June 1823, as a reporter for The Liberal.[92]

Curious visitors to the chapel, along with some uneasy regular members of the congregation,[93] would have been faced with a man of "uncommon height, a graceful figure and action, a clear and powerful voice, a striking, if not a fine face, a bold and fiery spirit, and a most portentous obliquity of vision" with, despite this slight defect, "elegance" of "the most admirable symmetry of form and ease of gesture", as well as "sable locks", a "clear iron-grey complexion, and firm-set features".[94]

Moreover, with the sheer novelty of a combination of the traits of an actor, a preacher, an author—even a pugilist—Irving

keeps the public in awe by insulting all their favourite idols. He does not spare their politicians, their rulers, their moralists, their poets, their players, their critics, their reviewers, their magazine-writers .... He makes war upon all arts and sciences, upon the faculties and nature of man, on his vices and virtues, on all existing institutions, and all possible improvement ...[95]

Irving, with his reactionary stance, has "opposed the spirit of the age".[96] Among those subjected to Irving's brutal verbal onslaughts were "Jeremy Bentham ... [with Irving looking] over the heads of his congregation to have a hit at the Great Jurisconsult in his study", as well as "Mr. Brougham ... Mr. Canning[97] ... Mr. Coleridge ... and ... Lord Liverpool" (Prime Minister at the time).[98] Of these notable figures, only Lord Liverpool did not rate his own chapter in The Spirit of the Age.

But Irving's popularity, which Hazlitt suspected would not last,[99] was a sign of another tendency of the age: "Few circumstances show the prevailing and preposterous rage for novelty in a more striking point of view, than the success of Mr. Irving's oratory."[100]

"Few circumstances show the prevailing and preposterous rage for novelty in a more striking point of view, than the success of Mr. Irving's oratory."

Part of Irving's appeal was due to the increased influence of evangelical Christianity, notes historian Ben Wilson; the phenomenon of an Edward Irving preaching to the great and famous would have been inconceivable thirty years earlier.[101] But the novelty of such a hitherto unseen combination of talents, Wilson concurs with Hazlitt, played no small part in Irving's popularity. And the inescapable fact of Irving's dominating physical presence, Wilson also agrees, had its effect. "William Hazlitt believed that no one would have gone to hear Irving had he been five feet high, ugly and soft-spoken."[102]

As a case in point, Hazlitt brings in Irving's own mentor, the Scottish theologian, scientist, philosopher, and minister Dr. Thomas Chalmers (1780–1847), whom Hazlitt had heard preach in Glasgow.[103] Comparing the published writings of both men, Chalmers was, thought Hazlitt, much more interesting as a thinker.[96] Although he ultimately dismisses Chalmers' arguments as "sophistry",[104] Hazlitt admires the elder clergyman's "scope of intellect" and "intensity of purpose".[96] His Astronomical Discourses were engaging enough that Hazlitt had eagerly read through the entire volume at a sitting.[105] His claim to our attention must rest on his writings; his unprepossessing appearance and ungainly manner in themselves, maintains Hazlitt, drew no audience. Chalmers' follower Irving, on the other hand, gets by on the strength of his towering physique and the novelty of his performances; judging him as a writer (his For the Oracles of God, Four Orations had just gone into a third edition),[106] Hazlitt finds that "the ground work of his compositions is trashy and hackneyed, though set off by extravagant metaphors and an affected phraseology ... without the turn of his head and wave of his hand, his periods have nothing in them ... he himself is the only idea with which he has yet enriched the public mind!"[105]

John Kinnaird suggests that in this essay, Hazlitt, with his "penetration" and "characteristically ruthless regard for truth", in his reference to Irving's "portentous obliquity of vision" insinuates that "one eye of Irving's imagination ... looks up to a wrathful God cast in his own image, 'endowed with all his own ... irritable humours in an infinitely exaggerated degree' [while] the other is always squinting askew at the prestigious image of Edward Irving reflected in the gaze of his fashionable audience—and especially in the rapt admiration of the 'female part of his congregation'".[107]

Kinnaird also notes that Hazlitt's criticism of Irving anticipated the judgement of Irving's friend, the essayist, historian, and social critic Thomas Carlyle, in his account of Irving's untimely death a few years later.[108]

The Late Mr. Horne Tooke

[edit]John Horne Tooke (1736–1812) was an English reformer, grammarian, clergyman, and politician. He became especially known for his support of radical causes and involvement in debates about political reform, and was briefly a Member of the British Parliament.[109] He was also known for his ideas about English grammar, published in ἔπεα πτερόεντα, or The Diversions of Purley (1786, 1805).[110]

By the time he was profiled as the third of "The Spirits of the Age" in Hazlitt's original series, Tooke had been dead for a dozen years. He was significant to Hazlitt as a "connecting link" between the previous age and the present. Hazlitt had known Tooke personally, having attended gatherings at his home next to Wimbledon Common until about 1808.[111]

"Mr. Horne Tooke", writes Hazlitt, "was in private company, and among his friends, the finished gentleman of the last age. His manners were as fascinating as his conversation was spirited and delightful."[112] Yet "his mind, and the tone of his feelings were modern."[113] He delighted in raillery, and prided himself on his cool, even temper. "He was a man of the world, a scholar bred, and a most acute and powerful logician ... his intellect was like a bow of polished steel, from which he shot sharp-pointed poisoned arrows at his friends in private, at his enemies in public."[113] Yet his thinking was one-sided: "he had no imagination ... no delicacy of taste, no rooted prejudices or strong attachments".[113]

Tooke's greatest delight, as seen by Hazlitt, was in contradiction, in startling others with radical ideas that at the time were considered shocking: "It was curious to hear our modern sciolist advancing opinions of the most radical kind without any mixture of radical heat or violence, in a tone of fashionable nonchalance, with elegance of gesture and attitude, and with the most perfect good-humour."[112]

His mastery of the art of verbal fencing was such that many eagerly sought invitation to his private gatherings, where they could "admire" his skills "or break a lance with him."[114] With a rapier wit, Tooke excelled in situations where "a ready repartee, a shrewd cross-question, ridicule and banter, a caustic remark or an amusing anecdote, whatever set [himself] off to advantage, or gratifie[d] the curiosity or piqued the self-love of the hearers, [could] keep ... attention alive and secure[d] his triumph ...." As a "satirist" and "a sophist" he could provoke "admiration by expressing his contempt for each of his adversaries in turn, and by setting their opinion at defiance."[115]

"It was his delight to make mischief and spoil sport. He would rather be against himself than for any body else."

Tooke was in Hazlitt's view much less successful in public life. In private, he could be seen at his best and afford amusement by "say[ing] the most provoking things with a laughing gaiety".[112] In public, as when he briefly served as a member of parliament, this attitude would not do. He did not really seem to believe in any great "public cause" or "show ... sympathy with the general and predominant feelings of mankind."[115] Hazlitt explains that "it was his delight to make mischief and spoil sport. He would rather be against himself than for any body else."[116]

Hazlitt also notes that there was more to Tooke's popular gatherings than verbal repartee. Having been involved in politics over a long life, Tooke could captivate his audience with his anecdotes, especially in his later years:

He knew all the cabals and jealousies and heart-burnings in the beginning of the late reign [of King George III], the changes of administration and the springs of secret influence, the characters of the leading men, Wilkes, Barrè, Dunning, Chatham, Burke, the Marquis of Rockingham, North, Shelburne, Fox, Pitt, and all the vacillating events of the American war:—these formed a curious back-ground to the more prominent figures that occupied the present time ...[117]

Hazlitt felt that Tooke would be longest remembered, however, for his ideas about English grammar. By far the most popular English grammar of the early 19th century was that of Lindley Murray, and, in his typical method of criticism by antitheses,[87] Hazlitt points out what he considers to be its glaring deficiencies compared to that of Tooke: "Mr. Lindley Murray's Grammar ... confounds the genius of the English language, making it periphrastic and literal, instead of elliptical and idiomatic."[118] Murray, as well as other, earlier grammarians, often provided "endless details and subdivisions"; Tooke, in his work commonly known by its alternate title of The Diversions of Purley, "clears away the rubbish of school-boy technicalities, and strikes at the root of his subject."[119] Tooke's mind was particularly suited for his task, as it was "hard, unbending, concrete, physical, half-savage ..." and he could see "language stripped of the clothing of habit or sentiment, or the disguises of doting pedantry, naked in its cradle, and in its primitive state."[119] That Murray's book should have been the grammar to have "proceeded to [its] thirtieth edition" and find a place in all the schools instead of "Horne Tooke's genuine anatomy of the English tongue" makes it seem, exclaims Hazlitt, "as if there was a patent for absurdity in the natural bias of the human mind, and that folly should be stereotyped!".[120]

A century and a half later, critic John Kinnaird saw this essay on Horne Tooke as being essential to Hazlitt's implicit development of his idea of the "spirit of the age". Not only did Tooke's thinking partake of the excessive "abstraction" that was becoming so dominant,[121] it constituted opposition for the sake of opposition, thereby becoming an impediment to any real human progress. It was this sort of contrariness, fuelled by "self-love", that, according to Kinnaird, is manifested in many of the later subjects of the essays in The Spirit of the Age.[122]

Hazlitt's criticism of Tooke's grammatical work has also been singled out. Critic Tom Paulin notes the way Hazlitt's subtle choice of language hints at the broader, politically radical implications of Tooke's linguistic achievement. Paulin observes also that Hazlitt, himself the author of an English grammar influenced by Tooke, recognised the importance of Tooke's grammatical ideas in a way that presaged and accorded with the radical grammatical work of William Cobbett, whom Hazlitt sketched in a later essay in The Spirit of the Age.[123]

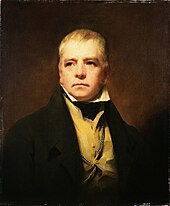

Sir Walter Scott

[edit]Sir Walter Scott (1771–1832), a Scottish lawyer and man of letters, was the most popular poet[124] and, beginning in 1814, writing novels anonymously as "The Author of Waverley ", the most popular author in the English language.[125] Hazlitt was an admirer as well as a reviewer of Scott's fiction, yet he never met the man, despite ample opportunities to do so.[126]

In Hazlitt's view, the essence of Scott's mind lay in its "brooding over antiquity."[120] The past provided nearly all his subject matter; he showed little interest in depicting modern life. This was true of his poetry as much as his prose. But, in Hazlitt's view, as a poet, his success was limited, even as a chronicler of the past. His poetry, concedes Hazlitt, has "great merit", abounding "in vivid descriptions, in spirited action, in smooth and glowing versification."[127] Yet it is wanting in "character ".[127] Though composed of "quaint, uncouth, rugged materials",[128] it is varnished over with a "smooth, glossy texture ... It is light, agreeable, effeminate, diffuse."[128] Hazlitt declares, "We would rather have written one song of Burns, or a single passage in Lord Byron's Heaven and Earth, or one of Wordsworth's 'fancies and good-nights,' than all of [Scott's] epics."[128]

The matter is altogether different with Scott the novelist.[129] The poems were read because they were fashionable. But the popularity of the novels was such that fanatically devoted readers fiercely debated the respective merits of their favourite characters and scenes.[130] Hazlitt, whose reviews had been highly favourable and appreciated these books as much as anyone, here elaborates on his own favourites, after first discussing a qualifying issue.[131] The greatest literary artists, Hazlitt had pointed out in the essay on Godwin, give shape to their creations by infusing them with imagination.[72] As creator of such works as Old Mortality, The Heart of Midlothian, and Ivanhoe, Scott, adhering closely to his sources, restricts his imaginative investment in the story, hemming himself in by the historical facts.[132] Even so, he manages to bring the past to life. He is the "amanuensis of truth and history" by means of a rich array of characters and situations.[131] Hazlitt recalls these characters in a rhapsodic passage, described by critic John Kinnaird as "a stunning pageant, two pages in length, of more than forty Scott characters, which he summons individually from his memory, citing for each some quality or act or association which makes them unforgettable."[133]

From Waverley, the first of these books, published in 1814, he recalls "the Baron of Bradwardine, stately, kind-hearted, whimsical, pedantic; and Flora MacIvor". Next, in Old Mortality, there are

that lone figure, like a figure in Scripture, of the woman sitting on the stone at the turning to the mountain, to warn Burley [of Balfour] that there is a lion in his path; and the fawning Claverhouse, beautiful as a panther, smooth-looking, blood-spotted; and the fanatics, Macbriar and Mucklewrath, crazed with zeal and sufferings; and the inflexible Morton, and the faithful Edith, who refused "to give her hand to another while her heart was with her lover in the deep and dead sea." And in The Heart of Midlothian we have Effie Deans (that sweet, faded flower) and Jeanie, her more than sister, and old David Deans, the patriarch of St. Leonard's Crags, and Butler, and Dumbiedikes, eloquent in his silence, and Mr. Bartoline Saddle-tree and his prudent helpmate, and Porteous, swinging in the wind, and Madge Wildfire, full of finery and madness, and her ghastly mother.[134]

He continues enthusiastically through dozens of others, exclaiming, "What a list of names! What a host of associations! What a thing is human life! What a power is that of genius! ... His works (taken together) are almost like a new edition of human nature. This is indeed to be an author!"[134]

Scott's "works (taken together) are almost like a new edition of human nature. This is indeed to be an author!"

Writing a century and a half later, critic John Kinnaird observes that Hazlitt was "Scott's greatest contemporary critic" and wrote the first important criticism of the novel, particularly in the form it was then beginning to assume.[135] Hazlitt's thinking on the new historical fiction of Scott was in the process of evolving.[71] Earlier, even to an extent in this essay, he had downplayed the novels as being little more than a transcription from old chronicles. But Hazlitt had begun to recognise the degree of imagination Scott had to apply in order to bring dry facts to life.[136]

Hazlitt also recognised that, at his best, Scott conveyed his characters' traits and beliefs impartially, setting aside his own political bias. Having faithfully and disinterestedly described "nature" in all its detail was in itself a praiseworthy accomplishment. "It is impossible", writes Hazlitt, "to say how fine his writings in consequence are, unless we could describe how fine nature is."[131] Kinnaird also notes Hazlitt's psychologically acute observation of how Scott, in taking us back to our more primitive past, recognised "the role of the repressed unconscious self in shaping modern literary imagination."[137] He sees Hazlitt, too, in The Spirit of the Age along with some other essays, as the first to recognise how Scott traced the action of historical forces through individual characters.[138]

Scott the man, laments Hazlitt, was quite different from Scott the poet and novelist. Even in his fiction, there is a notable bias, in his dramatisation of history, toward romanticising the age of chivalry and glorifying "the good old times".[139] Hazlitt sarcastically observes that Scott appeared to want to obliterate all of the achievements of centuries of civilised reform and revive the days when "witches and heretics" were burned "at slow fires", and men could be "strung up like acorns on trees without judge or jury".[140]

Scott was known to be a staunch Tory.[141] But what especially roused Hazlitt's ire was his association with the unprincipled publisher William Blackwood, the ringleader of a pack of literary thugs hired to smear the reputations of writers who expressed radical or liberal political views.[142] One of the pack was Scott's own son-in-law, John Gibson Lockhart. Hazlitt grants that Scott was "amiable, frank, friendly, manly in private life" and showed "candour and comprehensiveness of view for history".[143] Yet he also "vented his littleness, pique, resentment, bigotry, and intolerance on his contemporaries". Hazlitt concludes this account by lamenting that the man who was "(by common consent) the finest, most humane and accomplished writer of his age [could have] associated himself with and encouraged the lowest panders of a venal press ... we believe that there is no other age or country of the world (but ours), in which such genius could have been so degraded!"[143]

Lord Byron

[edit]Lord Byron (1788–1824) was the most popular poet of his day, a major figure of the English Romantic movement, and an international celebrity.[144] Although Hazlitt never met Byron, he had been following his career for years. Besides reviewing his poetry and some of his prose, Hazlitt had contributed to The Liberal, a journal Byron helped establish but later abandoned.[145]

"Intensity", writes Hazlitt, "is the great and prominent distinction of Lord Byron's writing. ... He grapples with his subject, and moves, and animates it by the electric force of his own feelings ... he is never dull".[146] His style is "rich and dipped in Tyrian dyes ... an object of delight and wonder".[147] Though he begins with "commonplaces", he "takes care to adorn his subject matter "with 'thoughts that breathe and words that burn' ... we always find the spirit of the man of genius breathing from his verse".[146] In Childe Harold's Pilgrimage, for example, though the subject matter is no more than "what is familiar to the mind of every school boy", Byron makes of it a "lofty and impassioned view of the great events of history", "he shows us the crumbling monuments of time, he invokes the great names, the mighty spirit of antiquity." Hazlitt continues, "Lord Byron has strength and elevation enough to fill up the moulds of our classical and time-hallowed recollections, and to rekindle the earliest aspirations of the mind after greatness and true glory with a pen of fire."[146]

Despite being impressed by such passages, Hazlitt also voices serious reservations about Byron's poetry as a whole:[148] "He seldom gets beyond force of style, nor has he produced any regular work or masterly whole." Hazlitt mentions having heard that Byron composed at odd times, whether inspired or not,[147] and this shows in the results, with Byron "chiefly think[ing] how he shall display his own power, or vent his spleen, or astonish the reader either by starting new subjects and trains of speculation, or by expressing old ones in a more striking and emphatic manner than they have been expressed before."[149]

Such "wild and gloomy romances" like "Lara, the Corsair, etc.", while often showing "inspiration", also reveal "the madness of poetry", being "sullen, moody, capricious, fierce, inexorable, gloating on beauty, thirsting for revenge, hurrying from the extremes of pleasure to pain, but with nothing permanent, nothing healthy or natural".[146]

Byron's dramas are undramatic. "They abound in speeches and descriptions, such as he himself might make either to himself or others, lolling on his couch of a morning, but do not carry the reader out of the poet's mind to the scenes and events recorded."[150] In this Byron follows most of his contemporaries, as Hazlitt argued in many of his critical writings, the tendency of the age, in imaginative literature as well as philosophical and scientific, being toward generalisation, "abstraction".[151] Also counteracting his immense power, the tone of even some of the best of Byron's poetry is violated by annoying descents into the ridiculous.[152] "You laugh and are surprised that any one should turn round and travestie himself". This is shown especially in the early parts of Don Juan, where, "after the lightning and the hurricane, we are introduced to the interior of the cabin and the contents of wash-hand basins."[152] After noting several such provoking incongruities, Hazlitt characterises Don Juan overall as "a poem written about itself" (he reserves judgement about the later cantos of that poem).[152]

The range of Byron's characters, Hazlitt contends, is too narrow. Returning again and again to the type that would later be called the "Byronic hero",[153] "Lord Byron makes man after his own image, woman after his own heart; the one is a capricious tyrant, the other a yielding slave; he gives us the misanthrope and the voluptuary by turns; and with these two characters, burning or melting in their own fires, he makes out everlasting centos of himself."[154]

Byron, observes Hazlitt, was born an aristocrat, but "he is the spoiled child of fame as well as fortune."[152] Always parading himself before the public, he is not satisfied simply to be admired; he "is not contented to delight, unless he can shock the public. He would force them to admire in spite of decency and common sense. ... His Lordship is hard to please: he is equally averse to notice or neglect, enraged at censure and scorning praise."[155] In his poetry—Hazlitt's example is the drama Cain—Byron "floats on swelling paradoxes" and "panders to the spirit of the age, goes to the very edge of extreme and licentious speculation, and breaks his neck over it."[155]

Lord Byron "is not contented to delight, unless he can shock the public. He would force them to admire in spite of decency and common sense. ... His Lordship is hard to please: he is equally averse to notice or neglect, enraged at censure and scorning praise."

In the course of characterising Byron, Hazlitt glances back to Scott, subject of the preceding chapter, and forward to Wordsworth and Southey, each of whom secures his own essay later in The Spirit of the Age. Scott, the only one of these writers who rivals Byron in popularity, notes Hazlitt in a lengthy comparison, keeps his own character offstage in his works; he is content to present "nature" in all its variety.[147] Scott "takes in half the universe in feeling, character, description"; Byron, on the other hand, "shuts himself up in the Bastile of his own ruling passions."[154]

While Byron's poetry, with all its power, is founded on "commonplaces", Wordsworth's poetry expresses something new, raising seemingly insignificant objects of nature to supreme significance. He is capable of seeing the profundity, conveying the effect on the heart, of a "daisy or a periwinkle", thus lifting poetry from the ground, "creat[ing] a sentiment out of nothing." Byron, according to Hazlitt, does not show this kind of originality.[146]

As for Robert Southey, Byron satirised Southey's poem "A Vision of Judgment"— which celebrates the late King George III's ascent to heaven—with his own The Vision of Judgment. Although Hazlitt says he does not much care for Byron's satires (criticising especially the heavy-handedness of the early English Bards and Scotch Reviewers),[150] he grants that "the extravagance and license of [Byron's poem] seems a proper antidote to the bigotry and narrowness of" Southey's.[156]

Hazlitt argues that "the chief cause of most of Lord Byron's errors is, that he is that anomaly in letters and in society, a Noble Poet. ... His muse is also a lady of quality. The people are not polite enough for him: the court not sufficiently intellectual. He hates the one and despises the other. By hating and despising others, he does not learn to be satisfied with himself."[156]

In conclusion—at least his originally intended conclusion—Hazlitt notes that Byron was now in Greece attempting to aid a revolt against Turkish occupation. With this sentence the chapter would have ended; but Hazlitt adds another paragraph, beginning with an announcement that he has just then learned of Byron's death. This sobering news, he says, has put "an end at once to a strain of somewhat peevish invective".[157]

Rather than withhold what he has written or refashion it into a eulogy, however, Hazlitt maintains that it is "more like [Byron] himself" to let stand words that were "intended to meet his eye, not to insult his memory."[158] "Death", Hazlitt concludes, "cancels everything but truth; and strips a man of everything but genius and virtue." Byron's accomplishments will be judged by posterity. "A poet's cemetery is the human mind, in which he sows the seeds of never-ending thought—his monument is to be found in his works. ... Lord Byron is dead: he also died a martyr to his zeal in the cause of freedom, for the first, last, best hopes of man. Let that be his excuse and his epitaph!"[158]

While Hazlitt showed an "obvious relish"[159] for some of Byron's poetry, on the whole his attitude toward Byron was never simple,[160] and later critics' assessments of Hazlitt's view of Byron's poetry diverge radically. Andrew Rutherford, who includes most of The Spirit of the Age essay on Lord Byron in an anthology of criticism of Byron, himself expresses the belief that Hazlitt had a "distaste for Byron's works".[161] Biographer Duncan Wu, on the other hand, simply notes Hazlitt's admiration for the "power" of Don Juan.[162] Biographer A. C. Grayling asserts that Hazlitt "was consistent in praising his 'intensity of conception and expression' and his 'wildness of invention, brilliant and elegant fancy, [and] caustic wit'."[148] John Kinnaird judges that Hazlitt, in assessing the relative merits of Wordsworth's and Byron's poetry, dismisses too readily as morbid the obsession with death in Byron's poetry, thus minimising one of its strengths.[163] David Bromwich emphasises the significance of Hazlitt's observation that Byron thought he stood "above his own reputation",[149] pointing out that Hazlitt ties this attitude to Byron's imperfect sympathy with the feelings common to all humanity, which in turn undermines the best in his poetry and diminishes its value relative to the best of Wordsworth's.[164]

Mr. Southey

[edit]Robert Southey (1774–1843) was a prolific author of poetry, essays, histories, biographies, and translations, and Poet Laureate of the United Kingdom from 1813 to 1843. Hazlitt first met Southey in London in 1799.[165] The two, along with Coleridge and Wordsworth, whom he had met not long before, were swept up in the movement supporting the rights of the common man that inspired much of the educated English population in the wake of the French Revolution.[166] During his brief career as a painter, until about 1803, Hazlitt spent time in the Lake District with Southey and the others, where they debated the future improvement of society as they rambled over the countryside.[167]

Years earlier, a reaction by the establishment to the reformers had already begun to set in,[168] and, after another fifteen years, the English political atmosphere had become stifling to the champions of liberty.[169] Wordsworth, Coleridge, and Southey all shifted their political allegiance to the right, which, among other things, drove a wedge between them and Hazlitt.[170] The alteration in Southey's politics was the sharpest. His earlier extreme radical position was implied in his play Wat Tyler, which seemed to advocate violent revolt by the lower classes. Now he expressed a stance of absolute support of the severest reprisals against any who dared criticise the government,[171] declaring that "a Reformer is a worse character than a housebreaker".[172] This opinion was put forth in an article in the conservative Quarterly Review, published—anonymously but widely believed (and later confessed) to be Southey's—in 1817, the same year his Wat Tyler was brought to light and published against his will, to Southey's embarrassment.[173] Hazlitt's reaction to Southey's abrupt about-face was a savage attack in the liberal Examiner. Wordsworth and Coleridge supported Southey and tried to discredit Hazlitt's attacks.[174]

By 1824, when Hazlitt reviewed the history of his relationship with Southey, his anger had considerably subsided. As with the other character sketches in The Spirit of the Age, he did his best to treat his subject impartially.[175]

He opens this essay with a painterly image of Southey as an embodiment of self-contradiction: "We formerly remember to have seen him [with] a hectic flush on his cheek [and] a smile betwixt hope and sadness that still played upon his quivering lip."[158] Hazlitt continues:

While he supposed it possible that a better form of society could be introduced than any that had hitherto existed ... he was an enthusiast, a fanatic, a leveller ... in his impatience of the smallest error or injustice, he would have sacrificed himself and his generation (a holocaust) to his devotion to the right cause. But when ... his chimeras and golden dreams of human perfectibility once vanished from him, he turned suddenly round, and maintained that "whatever is, is right".... He is ever in extremes, and ever in the wrong![176]

In a detailed psychological analysis, Hazlitt explains Southey's self-contradiction: rather than being wedded to truth, he is attached to his own opinions, which depend on "the indulgence of vanity, of caprice, [of] prejudice ... regulated by the convenience or bias of the moment." As a "politician", he is governed by a temperament that is fanciful, "poetical, not philosophical."[177] He "has not patience to think that evil is inseparable from the nature of things."[176] Hazlitt's explanation is that, despite Southey's changing opinions, based on "impressions [that] are accidental, immediate, personal", he is "of all mortals the most impatient of contradiction, even when he has turned the tables on himself." This is because at bottom he knows his opinions have nothing solid to back them. "Is he not jealous of the grounds of his belief, because he fears they will not bear inspection, or is conscious he has shifted them? ... He maintains that there can be no possible ground for differing from him, because he looks only at his own side of the question!"[177] "He treats his opponents with contempt, because he is himself afraid of meeting with disrespect! He says that 'a Reformer is a worse character than a house-breaker,' in order to stifle the recollection that he himself once was one!"[177]

Despite Southey's then assumed public "character of poet-laureat and courtier",[177] his character at bottom is better suited to the role of reformer. "Mr. Southey is not of the court, courtly. Every thing of him and about him is from the people."[178] As evidenced in his writings, "he bows to no authority; he yields only to his own wayward peculiarities." His poetic eulogy of the late King George III, for example, which had been mercilessly mocked by Byron, was, oddly, also a poetic experiment, "a specimen of what might be done in English hexameters."[178]

Mr. Southey is "ever in extremes, and ever in the wrong!"

Surveying the range of Southey's voluminous writings, constituting a virtual library,[179] Hazlitt finds worth noting "the spirit, the scope, the splendid imagery, the hurried and startled interest"[179] of his long narrative poems, with their exotic subject matter. His prose volumes of history, biography, and translations from Spanish and Portuguese authors, while they lack originality, are well researched and are written in a "plain, clear, pointed, familiar, perfectly modern" style that is better than that of any other poet of the day, and "can scarcely be too much praised."[180] In his prose, "there is no want of playful or biting satire, of ingenuity, of casuistry, of learning and of information."[180]

Southey's major failing is that, with a spirit of free inquiry that he cannot suppress in himself, he attempts to suppress free inquiry in others.[181] Yet, even in Southey's political writings, Hazlitt credits him as refraining from advocating what might be practised by "those whose hearts are naturally callous to truth, and whose understandings are hermetically sealed against all impressions but those of self-interest".[181] He remains, after all, "a reformist without knowing it. He does not advocate the slave-trade, he does not arm Mr. Malthus's revolting ratios with his authority, he does not strain hard to deluge Ireland with blood."[181]

In Southey's personal appearance, there is something eccentric, even off-putting: he "walks with his chin erect through the streets of London, and with an umbrella sticking out under his arm, in the finest weather."[178] "With a tall, loose figure, a peaked austerity of countenance, and no inclination to embonpoint, you would say he has something puritanical, something ascetic in his appearance."[179] Hazlitt hopes the negative aspects of his character will dissipate, wishing that Southey live up to his own ideal as expressed in his poem "The Holly-Tree" so that "as he mellows into maturer age, all [his] asperities may wear off...."[180]

Continuing with a more balanced view than any he had expressed before, Hazlitt notes Southey's many fine qualities: he is a tireless worker, "is constant, unremitting, mechanical in his studies, and the performance of his duties. ... In all the relations and charities of private life, he is correct, exemplary, generous, just. We never heard a single impropriety laid to his charge."[182] "With some gall in his pen, and coldness in his manner, he has a great deal of kindness in his heart. Rash in his opinions", concludes Hazlitt, Southey "is steady in his attachments—and is a man, in many particulars admirable, in all respectable—his political inconsistency alone excepted!"[182]

Historian Crane Brinton a century later applauded Hazlitt's "fine critical intelligence" in judging Southey's character and works.[183] Later, Tom Paulin, with admiration for the richness of Hazlitt's style, traced his writing on Southey from the "savage" attacks in 1816 and 1817[184] through the more balanced assessment in this sketch. Paulin especially notes allusive and tonal subtleties in Hazlitt's poetic prose that served to highlight, or at times subtly qualify, the portrait of Southey he was trying to paint. This, Paulin observes, is an example of how Hazlitt "invest[s] his vast, complex aesthetic terminology with a Shakespearean richness ... perhaps the only critic in English" to do so.[185]

Mr. Wordsworth

[edit]William Wordsworth (1770–1850) was an English poet, often considered, with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, to have inaugurated the Romantic movement in English poetry with the publication in 1798 of their Lyrical Ballads. Hazlitt was introduced to Wordsworth by Coleridge, and both had a shaping influence on him, who was privileged to have read Lyrical Ballads in manuscript. Though Hazlitt was never close with Wordsworth, their relationship was cordial for many years.[186] As between Coleridge and Hazlitt, as well as Southey and Hazlitt, differences between Wordsworth and Hazlitt over politics were a major cause of the breakdown of their friendship.

But there was another cause for the rupture. Hazlitt had reviewed Wordsworth's The Excursion in 1814, approvingly, but with serious reservations.[187] Wordsworth's poetry was appreciated by few at that time. The Excursion was notoriously demeaned by the influential Francis Jeffrey in his Edinburgh Review criticism beginning with the words, "This will never do",[188] while Hazlitt's account was later judged to have been the most penetrating of any written at the time.[189] Still, Wordsworth was unable to tolerate less than unconditional acceptance of his poetry,[190] and he resented Hazlitt's review as much as he did Jeffrey's.[191] Their relations deteriorated further, and by 1815 they were bitter enemies.[192]

Despite his grievous disappointment with a man he had once thought an ally in the cause of humanity, after nearly ten years of severe and sometimes excessive criticism of his former idol (some of it in reaction to Wordsworth's attempt to impugn his character),[193] as with his other former friends of the period, in The Spirit of the Age Hazlitt attempts to reassess Wordsworth as fairly as he can.[194] For all of Wordsworth's limitations, he is after all the best and most representative poetic voice of the period:

"Mr. Wordsworth's genius is a pure emanation of the Spirit of the Age."[182] His poetry is revolutionary in that it is equalizing.[195] Written more purely in the vernacular style than any earlier poetry, it values all humanity alike rather than taking an aristocratic viewpoint. It is something entirely new: Mr. Wordsworth "tries to compound a new system of poetry from [the] simplest elements of nature and of the human mind ... and has succeeded perhaps as well as anyone could."[196]

Wordsworth's poetry conveys what is interesting in the commonest events and objects. It probes the feelings shared by all. It "disdains" the artificial,[195] the unnatural, the ostentatious, the "cumbrous ornaments of style",[197] the old conventions of verse composition. His subject is himself in nature: "He clothes the naked with beauty and grandeur from the stores of his own recollections". "His imagination lends 'a sense of joy to the bare trees and mountains bare, and grass in the green field'. ... No one has shown the same imagination in raising trifles into importance: no one has displayed the same pathos in treating of the simplest feelings of the heart."[197]

"There is no image so insignificant that it has not in some mood or other found its way into his heart...." He has described the most seemingly insignificant objects of nature in such "a way and with an intensity of feeling that no one else had done before him, and has given a new view or aspect of nature. He is in this sense the most original poet now living...."[198]

"Mr. Wordsworth's genius is a pure emanation of the Spirit of the Age."

Hazlitt notes that, in psychological terms, the underlying basis for what is essential in Wordsworth's poetry is the principle of the association of ideas. "Every one is by habit and familiarity strongly attached to the place of his birth, or to objects that recal the most pleasing and eventful circumstances of his life. But to [Wordsworth], nature is a kind of home".[198]

Wordsworth's poetry, especially when the Lyrical Ballads had been published 26 years earlier, was such a radical departure that scarcely anyone understood it. Even at the time Hazlitt was writing this essay, "The vulgar do not read [Wordsworth's poems], the learned, who see all things through books, do not understand them, the great despise, the fashionable may ridicule them: but the author has created himself an interest in the heart of the retired and lonely student of nature, which can never die."[198] "It may be considered as a characteristic of our poet's writings," Hazlitt reflects, "that they either make no impression on the mind at all, seem mere nonsense-verses, or that they leave a mark behind them that never wears out. ... To one class of readers he appears sublime, to another (and we fear the largest) ridiculous."[199]

Hazlitt then briefly comments on some of Wordsworth's more recent "philosophical production" which (for example, "Laodamia") he finds "classical and courtly ... polished in style without being gaudy, dignified in subject without affectation."[200] As in the earlier sketches, Hazlitt finds links between his earlier and later subjects. If there are a few lines in Byron's poems that give him the heartfelt satisfaction that so many of Wordsworth's poems do, it is only when "he descends with Mr. Wordsworth to the common ground of a disinterested humanity" by "leaving aside his usual pomp and pretension."[200]

Ten years earlier Hazlitt had reviewed what was then Wordsworth's longest and most ambitious published poem, The Excursion, and he briefly remarks on it here. Though he does not disdainfully dismiss it as Jeffrey had, he expresses serious reservations. It includes "delightful passages ... both of natural description and of inspired reflection [yet] it affects a system without having an intelligible clue to one."[201] The Excursion suffers from what Hazlitt highlights as a major flaw in contemporary poetry in general: it tends toward excessive generalisation, "abstraction". Thus it ends up being both inadequate philosophy and poetry that has detached itself from the essence and variety of life.[202]

As in his essays in this book on other subjects he had seen personally, Hazlitt includes a sketch of the poet's personal appearance and manner: "Mr. Wordsworth, in his person, is above the middle size, with marked features, and an air somewhat stately and Quixotic."[203] He is especially effective at reading his own poetry. "No one who has seen him at these moments could go away with the impression that he was a man 'of no mark or likelihood.'"[201]

Then Hazlitt comments on the nature of Wordsworth's taste in art and his interest in and judgements of artists and earlier poets. His tastes show the elevation of his style, but also the narrowness of his focus. Wordsworth's artistic sympathies are with Poussin and Rembrandt, showing an affinity for the same subjects. Like Rembrandt, he invests "the minute details of nature with an atmosphere of sentiment".[204] Wordsworth has little sympathy with Shakespeare. Related to this, asserts Hazlitt, is the undramatic nature of Wordsworth's own poetry. This is the result of a character flaw, egotism.[205] He regrets his own harsh criticism of a few years earlier,[206] but still maintains that Wordsworth's egotism, narrowing the range of his interests, restricts his literary achievement. And yet, Hazlitt reflects, as is frequently the case with men of genius, an egotistic narrowness is often found together with an ability to do one thing supremely well.[207]

Hazlitt concludes with a psychological analysis of the effect on Wordsworth's character of his disappointment with the poor reception of his poetry.[208] But he ends on a note of optimism. Wordsworth has gained an increasing body of admirers "of late years". This will save him from "becoming the God of his own idolatry!"[209]

The 20th-century critic Christopher Salvesen notes that Hazlitt's observation in The Spirit of the Age that Wordsworth's poetry is "synthetic"[201] characterises it best,[210] and Roy Park in an extensive study expresses the view that Hazlitt, as the poet's contemporary, most completely understood the essence of his poetry as a significant component of the "spirit of the age".[211]

Sir James Mackintosh

[edit]Sir James Mackintosh (1765–1832), widely admired as one of the most learned men in Europe, was a Scottish lawyer, legislator, educator, philosopher, historian, scholar, and Member of Parliament from 1813 to 1830. Mackintosh came to Hazlitt's attention as early as 1791, when he published his Vindiciae Gallicae, a defence of the French Revolution, then unfolding. Written as a response to Edmund Burke's Reflections on the Revolution in France, it was warmly received by liberal thinkers of the time.[212] However, later persuaded by Burke himself to renounce his earlier views about the Revolution, Mackintosh, in his 1799 lectures at Lincoln's Inn (published as A Discourse on the Study of the Law of Nature and Nations), attended by Hazlitt, reversed his position, subjecting reformers, particularly Godwin, to severe criticism, and dealing a blow to the liberal cause.[213]

Mackintosh thereafter became a bitter disappointment to Hazlitt. Looking back at the elder man's change of political sentiments, Hazlitt observed that the lecturer struck a harsh note if he felt it were a triumph to have exulted in the end of all hope for the "future improvement" of the human race; rather it should have been a matter for "lamentation".[214] The two later again crossed paths, when Hazlitt, as a political reporter, attended Mackintosh's "maiden speech" in Parliament, in 1813,[215] leading Hazlitt to think deeply about what constitutes an effective speech in a legislative body (Mackintosh's was presented as a counter-example in Hazlitt's 1820 essay on the subject).[216] By this time, Mackintosh's return to the liberal camp had begun to take the edge off Hazlitt's bitterness, although he regretted that the nature of his talents kept Mackintosh from being an effective ally in Parliament.[217]

Eleven years later, in his summing up of Mackintosh's place among his contemporaries, as elsewhere in The Spirit of the Age, Hazlitt attempts a fair reassessment. As he analyses the characteristics of Mackintosh as a public speaker, a conversationalist, and a scholarly writer, Hazlitt traces the progress of his life, noting his interactions with Edmund Burke over the French Revolution, his tenure as chief judge in India, and his final career as Member of Parliament.

"As a writer, a speaker, and a converser", he begins, Mackintosh is "one of the ablest and most accomplished men of the age", "a man of the world", and a "scholar" of impressive learning, "master of almost every known topic".[209] "His Vindiciae Gallicae is a work of great labour, great ingenuity, great brilliancy, and great vigour."[218] After he changed political sides for a time, Mackintosh then began to excel as an "intellectual gladiator". Of his qualifications in this regard, Hazlitt remarks, "Few subjects can be started, on which he is not qualified to appear to advantage as the gentleman and scholar. ... There is scarce an author he has not read; a period of history he is not conversant with; a celebrated name of which he has not a number of anecdotes to relate; an intricate question that he is not prepared to enter upon in a popular or scientific manner."[219]

As he praises Mackintosh's impressive talents and intellect, however, Hazlitt also brings out his limitations. In demolishing his adversaries, including Godwin and the reformers in his famous lectures, Mackintosh "seemed to stand with his back to the drawers in a metaphysical dispensary, and to take out of them whatever ingredients suited his purpose. In this way he had an antidote for every error, an answer to every folly. The writings of Burke, Hume, Berkeley, Paley, Lord Bacon, Jeremy Taylor, Grotius, Puffendorf, Cicero, Aristotle, Tacitus, Livy, Sully, Machiavel, Guicciardini, Thuanus, lay open beside him, and he could instantly lay his hand upon the passage, and quote them chapter and verse to the clearing up of all difficulties, and the silencing of all oppugners."[220] But there is a fatal flaw in all this impressive intellectual "juggling"[221] (which, Tom Paulin notes, alludes to Hazlitt's earlier contrast between the deft but mechanical "Indian jugglers" and representatives of true genius):[222] his performances were "philosophical centos", the thoughts of others simply stitched together. "They were profound, brilliant, new to his hearers; but the profundity, the brilliancy, the novelty were not his own."[220] For all his impressive erudition, Mackintosh's writing and speaking are entirely unoriginal.

Sir James "strikes after the iron is cold."

In his characteristic fashion, Hazlitt looks back to an earlier subject of these essays and compares Mackintosh with Coleridge. While the latter's genius often strays from reality, his imagination creates something new. Mackintosh, on the other hand, with a similarly impressive command of his subject matter, mechanically presents the thinking of others. There is no integration of his learning with his own thinking, no passion, nothing fused in the heat of imagination.[218]