The Red Christ

| The Red Christ | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Lovis Corinth |

| Year | 1922 |

| Medium | Oil on wood |

| Dimensions | 129 cm × 108 cm (51 in × 43 in) |

| Location | Pinakothek der Moderne, Munich |

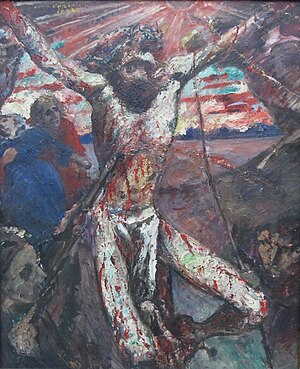

'The Red Christ is an oil on wood painting by the German painter Lovis Corinth, from 1922. It is a depiction of the crucifixion of Jesus Christ, belonging to his expressionist phase. The painting is signed and dated in yellow in two lines on the upper left: “Lovis Corinth 1922 ”. It is held in the Pinakothek der Moderne, in Munich.[1]

This work belongs to a group of religious paintings where Corinth took inspiration by the episodes of the crucifixion and the Passion of Christ. He painted this expressionist work on wood, not in canvas, similarly to the historical altarpieces. His last painting, a self-portrait where he portrays the suffering Christ (Ecce Homo), from 1925, also deals with this theme.

Description

[edit]The painting depicts a crucifixion scene, with the body of Jesus Christ in the center, slightly moved to the left edge. Neither His hands nor the horizontal beam of the cross are seen. The feet and the right knee touch the lower edge of the painting. According to Sonja de Puinef, the body of the suffering Christ "dominates and breaks up" the composition "with his hands protruding above the picture frame".[2] The scene, according to the same art historian, is thus "fitted very precisely into the unusually crowded picture space." The body, tilting to the left towards the viewer, hangs on the cross with outstretched arms and bent knees. The head with the crown of thorns has fallen to the side onto the left shoulder. The eyes of Jesus look forward and thus towards the viewer. His naked and bleeding body is largely depicted in white. A loincloth covers his nakedness. The cross is only visible in the lower part of the painting. In the upper part it is outshone by the sun; its crossbeam lies outside the picture. The viewer can only suppose how and whether the body of Jesus is fixed.

A man standing in the lower left of the picture is thrusting a lance into the crucified Christ, below his left breast; blood is spurting from the wound. The man is probably Longinus, the Roman soldier mentioned in the Bible, but whose names comes from tradition, who is mentioned to have stabbed Jesus with a spear after his death. Above him, there are two other figures, they are supposed to represent the Apostle John and the Virgin Mary. John, dressed in a red robe, stands slightly offset behind the unconscious Mary in her blue robe. On the right side there is another figure, who is holding a sponge on a long staff, a branch of hyssop, who according to the Gospel of John, was soaked in vinegar. All the people, except the unconscious Mary, are looking from their positions in the direction of the crucified body of Jesus.[3]

The background is a three-part composition. While there are three other people at the left of the crucified Jesus, the landscape is indistinctly depicted on the right, and only a single person appears in the lower section. The landscape in the painting represents a lake instead of the Mount Golgotha, where the crucifixion is believed to have taken place, according the New Testament. The horizon line is shown at the chest height of the crucified Jeus, above that there is the sky, and in the third section between the outstretched arms, the sun is depicted with accentuated rays of sunlight. The sky, the lake, and the sun are all permeated with red, creating an impression of twilight.ref>Sonja de Puinef, "Der rote Christus", in Ulrike Lorenz, Marie-Amélie zu Salm-Salm, Hans-Werner Schmiedt (coordinators), Lovis Corinth und die Geburt der Moderne, Kerber, Bielefeld, 2008 (German)</ref>

Analysis

[edit]The crucifixion scene depicted corresponds in its basic features to the way it is described in the Gospel of John. It is a summary of several scenes described in John 19:29; 34, and encompassing the death of Jesus Christ.

Corinth painted the work in wood following the tradition of altarpieces by German and Dutch masters of the Renaissance. The depiction is described by Andrea Bärnreuther as “the most horrific interpretation of the theme”, depicting "brutally"! the “horror of martyrdom”. According to Bärnreuther, Corinth chose the expressionist style because of his “insight into the limits of naturalistic representation, which must fail where it is about the intangible, not immediately accessible to the senses.”[4] Bärnreuther also recognizes in the style of representation an “aesthetic of the ugly” that goes “beyond aesthetic limits” and “in which the brutality of the abstraction in the figure, the arbitrariness in the coloring of the omnipresent red that violates all rules of good taste and, last but not least, the violent application of paint in the thick patches and the maltreating treatment with palette knife and brush” represent an “attack on perception.”

Sonja de Puinef places the picture in the context of the political situation in Germany, and in Corinth's personal situation, in 1922. That year, Germany faced a severe inflation. At the same time, Corinth's physical health and mental state were at a low point. According to de Puinef, "his Christ with uncertain facial features is undoubtedly also a projection of the suffering of the artist himself and, beyond him, of an entire nation." She also explains that Corinth chose "a religious subject of universal significance in order to express his personal shock."[5]

Context

[edit]The painting The Red Christ was created in 1922 and is one of the late works of the artist, who was then 64 years old. It is one of the numerous depictions of the Passion of Jesus Christ that Corinth made during his career. His first painting on the subject was a Descent from the Cross (1895), and his last painting before his death was a self-portrait in the role of the Ecce Homo (1925). His style developed from a naturalist, as in the Descent from the Cross to an expressionist, as shown in The Red Christ and Ecce Homo.[6]

Provenance

[edit]The Red Christ was first exhibited in the Berlin Secession in 1922. Until 1956, it was in the collection by the artist's wife, Charlotte Berend-Corinth, who took it with her when she emigrated to the United States in 1939. It came into the possession of the Bavarian State Painting Collections in 1956.[7]

References

[edit]- ^ Andrea Bärnreuther, "Der rote Christus", in Peter-Klaus Schuster, Christoph Vitali, Barbara Butts (coordinators), Lovis Corinth, Prestel, Munich, 1996, pp. 266–267 (German)

- ^ Sonja de Puinef, "Der rote Christus", in Ulrike Lorenz, Marie-Amélie zu Salm-Salm, Hans-Werner Schmiedt (coordinators), Lovis Corinth und die Geburt der Moderne, Kerber, Bielefeld, 2008 (German)

- ^ Barbara Butts, "Gekreuzigter Christus", in Peter-Klaus Schuster, Christoph Vitali, Barbara Butts (coordinators), Lovis Corinth, Munich, Prestel, 1996

- ^ Andrea Bärnreuther, "Der rote Christus", in Peter-Klaus Schuster, Christoph Vitali, Barbara Butts (coordinators), Lovis Corinth, Prestel, Munich, 1996, pp. 266–267 (German)

- ^ Sonja de Puinef, "Der rote Christus", in Ulrike Lorenz, Marie-Amélie zu Salm-Salm, Hans-Werner Schmiedt (coordinators), Lovis Corinth und die Geburt der Moderne, Bielefeld, Kerber, 2008 (German)

- ^ Horst Uhr, Lovis Corinth, Berkeley and Los Angeles, California Press, 1990

- ^ Charlotte Berend-Corinth, Lovis Corinth. Werkverzeichnis, new version by Béatrice Hernad, Munich, Bruckmann Verlag, 1958, 1992 (German)