The Overlanders (film)

| The Overlanders | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Harry Watt |

| Written by | |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Osmond Borradaile |

| Edited by | |

| Music by | John Ireland |

Production company | |

| Distributed by |

|

Release dates |

|

Running time | 91 minutes |

| Countries |

|

| Language | English |

| Budget | £40,000[1] or £80,000[2] or £130,000[3] |

| Box office | £160,000 (Australia)[4] 1,143,888 admissions (France)[5] £250,000 (total)[2] |

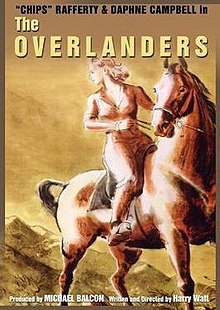

The Overlanders is a 1946 British-Australian Western film about drovers driving a large herd of cattle 1,600 miles (2,575 km) overland from Wyndham, Western Australia through the Northern Territory outback of Australia to pastures north of Brisbane, Queensland, during World War II.

The film was the first of several produced in Australia by Ealing Studios and featured among the cast Chips Rafferty. It was an early example of the genre later dubbed the "meat pie western".

Plot

[edit]In 1942, the Japanese army is thrusting southwards and Australia fears invasion. Bill Parsons becomes concerned, and leaves his homestead in northern Australia along with his wife and two daughters, Mary and Helen. They join up with a cattle drive heading south led by Dan McAlpine. Others on the drive include the shonky Corky; British former sailor, Sinbad; Aboriginal stockmen, Nipper and Jackie.

The cattle drive is extremely difficult, encountering crocodiles, blazing heat and other dangers. Mary and Sinbad start a romance. Dan speaks out against Corky's plans to develop the Northern Territory.

Cast

[edit]- Chips Rafferty as Dan McAlpine

- John Nugent Hayward as Bill Parsons

- Daphne Campbell as Mary Parsons

- Jean Blue as Mrs Parsons

- Helen Grieve as Helen Parsons

- John Fernside as Corky

- Peter Pagan as Sinbad

- Frank Ransome as Charlie

- Stan Tolhurst as Bert

- Marshall Crosby as Minister

- Clyde Combo as Jackie

- Henry Murdoch as Nipper

- Edmund Allison as two-up player

- Jock Levy as two-up player

- John Fegan as Police Sergeant

- Steve Dodd

Development

[edit]The film came about because the Australian government was concerned that Australia's contribution to the war effort was not being sufficiently recognised. It contacted the British Ministry of Information, who in turn spoke with Michael Balcon at Ealing Studios, who was enthusiastic about the idea of making a film in Australia. He sent Harry Watt to Australia to find a subject. Watt travelled the country as an official war correspondent and guest of the Australian government. He spent eighteen months in Australia making the film.[1]

Watt decided to exploit the Australian landscape, by making a film set entirely outdoors. When visiting a government office in Canberra to advise on making documentaries, he heard about an incident in 1942, when 100,000 cattle were driven 2,000 miles (3,218.7 km) in the Northern Territory to escape a feared Japanese invasion.[6]

Watt was allowed to import only four technicians from Britain to assist – editor Inman Hunter, cinematographer Osmond Borradaile, production supervisor Jack Rix[7] and camera operator Carl Kayser. The rest of the crew was drawn from Australia. The sound recording engineer was Beresford Charles Hallett.[8][9]

Watt spent 1944 travelling the route of the trek. Dora Birtles researched the subject in government files and archives. She later wrote a novelisation of the script, which was published.

Casting

[edit]There were nine lead roles and the casting process took two months.[10] Watt ended up selecting four professional actors, an experienced amateur and four newcomers to films. Chips Rafferty, whom Watt described as an "Australian Gary Cooper",[11] was given his first lead role. Daphne Campbell was a nursing orderly who had grown up in the country, but had never acted before. She was screen-tested after her picture was seen on the cover of a magazine, and selected over hundreds of applicants.[12] Peter Pagan had worked in Sydney theatre and was serving in the army, when selected by Watt.[13]

Clyde Combo and Henry Murdoch were cast as the Aboriginal stockmen; they came from Palm Island because Harry Watt believed Northern Territory Aboriginal people did not speak English sufficiently well.[14] New South Wales Aboriginal activist Bill Onus appeared in a minor role.[15]

Chips Rafferty and John Nugent-Hayward were paid £25 a month for five months.[16]

Production

[edit]Five hundred cattle were purchased by Ealing for use in the film. They were marked with the "overland" brand and later sold off, for profit.

Shooting began in April 1945 at Sydney's North Head Quarantine Station, which stood in for the meat export centre at Wyndham, in Western Australia.[17] The unit was then flown by the RAAF to Alice Springs, where they were based in an army camp.[10]

A second unit headed by John Heyer spent several weeks filming movement of cattle from the air.[18]

Three months later, the unit moved to the Roper River camp on the Elsey Station for another month, where the river crossing sequence was shot. This station was famous from the book We of the Never Never. In mid-September, the unit returned to Sydney after five months of shooting.[19]

During the making of the film, Campbell met and married her future husband.[20]

The Australian government later declared they spent £4,359 to assist in the production of the film.[21]

Post-production work was done in Britain. The film score was written by the English composer John Ireland, his only film score. Ireland wrote to a friend "the subject of the film is one I can perhaps tackle... and the music director will be very helpful, tending my inexperience". He also liked the fact that there were no stars, and although he had never been to Australia, the challenge of portraying the landscapes and natural world.[22] He stayed in London with easy access to Ealing during the composition; he commented that "it needs a lot of heavy, symphonic music, and what I have done is extremely good and will make an excellent concert suite".[22] After Ireland's death an orchestral suite was extracted from the score by the conductor Sir Charles Mackerras[23] in 1965 consisting of a march 'Scorched Earth', a romance 'Mary and the Sailor', an intermezzo 'Open Country', a scherzo 'Brumbies', and as a finale 'Night Stampede'.[22]

Harry Watt claimed the original ending was more cynical, finishing with the unscrupulous 'Corky' being the only one who got a good job out of the trek, and a fade out on a roar of sardonic laughter from the rest of the overlanders. However, he says he was advised to put a more upbeat ending.[24]

Ealing were so pleased with Rafferty's performance, they signed him to a long-term contract even before the film had been released.

Post-production

[edit]According to Leslie Norman, Harry Watt was not satisfied with the editing job done by Inman Hunter, "so, they asked me to take it over. I actually ripped it all apart and started over again. But, I thought this could ruin Ted Hunter's career so I suggested they credit him as editor and I would take the title of supervising editor."[25]

Reception

[edit]Neither Rafferty, nor Campbell were able to make the film's Sydney premiere because Rafferty was making a film in the UK, and Campbell was looking after her one-week-old baby in Alice Springs. However local actor Ron Randell attended and was mobbed.[20]

Critical

[edit]Reviews were extremely positive.[26] The Monthly Film Bulletin stated that, without the "tawdry "fictionalisation"", it was a worthy film, "with many fine directorial details, accurate if broad characterisation, and full exploitation of periodic climactic incident", and that "it succeeds magnificently in capturing the authentic drama of its setting and its main action". However, what it couched as 'fictional' elements were less successful: "It begins self-consciously, tails badly in its final few minutes. Particularly it fumbles with the personal dramas inevitable in a tiny community living in close proximity in circumstances like these...".[27]

Years later Filmink magazine said "This is one of the best of the meat pie Westerns – it takes a very American concept, the cattle drive, and grounds it in the local culture. Sure, there's stampedes and romance, but no outlaws and shoot outs, and there's a feisty "squatter's daughter" character who is sensibly given a romance with Peter Pagan rather than Chips Rafferty."[28]

Box office

[edit]The film was enormously successful at the box office in Australia and Britain; by February 1947 it was estimated 350,000 Australians had seen it, making it the most widely seen Australian film of all time.[29]

According to trade papers, the film was a "notable box office attraction" at British cinemas in 1946.[30] According to one report it was the 11th most popular film at the British box office in 1946 after The Wicked Lady, The Bells of St. Mary's, Piccadilly Incident, The Captive Heart, Road to Utopia, Caravan, Anchors Away, The Corn is Green, Gilda, and The House on 92nd Street'.[31] According to Kinematograph Weekly the 'biggest winner' at the box office in 1946 Britain was The Wicked Lady, with "runners up" being: The Bells of St Marys, Piccadilly Incident, The Road to Utopia, Tomorrow is Forever, Brief Encounter, Wonder Man, Anchors Away, Kitty, The Captive Heart, The Corn is Green, Spanish Main, Leave Her to Heaven, Gilda, Caravan, Mildred Pierce, Blue Dahlia, Years Between, O.S.S., Spellbound, Courage of Lassie, My Reputation, London Town, Caesar and Cleopatra, Meet the Navy, Men of Two Worlds, Theirs is the Glory, The Overlanders, and Bedelia.[32]

It was also the first Ealing picture to be widely seen in Europe.

US release

[edit]Some minor changes for censorship were made for the film's US release including the removal of the word "damn".[33] The film was listed one of the 15 best films of the year by Bosley Crowther of the New York Times.[34]

The movie was distributed in the US by a prestige department of Universal, a company created specifically to distribute British films from the Rank Organisation. The Overlanders was the second most popular of such movies, after Brief Encounter (1945).[35]

Impact

[edit]This acclaim prompted Ealing (and its parent company, Rank, who distributed) to make a series of films in Australia out of Pagewood Film Studios.[6] Among the first discussed projects was an adaptation of the James Aldridge novel, Signed with Their Honour.[36]

By mid-1947, it appeared the company would make a co-production deal with Cinesound Productions, but in August, Sir Norman Rydge withdrew Cinesound. Ealing went ahead by themselves to make Eureka Stockade with Chips Rafferty.

Daphne Campbell received Hollywood enquiries and made a series of screen tests in Sydney, but elected not to pursue a Hollywood career, staying with her husband and children in Alice Springs.[37] Peter Pagan moved overseas and worked extensively in the US and London.

Home media

[edit]The Overlanders was released on DVD by Umbrella Entertainment in November 2012. The DVD is compatible with all region codes.[38]

Ireland's music has been recorded commercially several times; by the London Symphony Orchestra conducted by Muir Mathieson (two sides of a 78rpm Decca LP in 1947),[39] the London Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Adrian Boult (the suite, for Lyrita in 1971),[40] the London Symphony Orchestra conducted by Richard Hickox (the suite, for Chandos in 1991),[41] The Hallé conducted by John Wilson (the suite in 2007), and the complete score by the Royal Scottish National Orchestra conducted by Martin Yates (Dutton, 2018).

References

[edit]- ^ a b Andrew Pike and Ross Cooper, Australian Film 1900–1977: A Guide to Feature Film Production, Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 1998, 204.

- ^ a b "The research bureau holds an autopsy". Sunday Mail. Brisbane. 17 February 1952. p. 11. Retrieved 28 April 2013 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Tomholt, Sydney (23 September 1950). "FILMS Cost of Australian Productions". ABC Weekly. p. 30.

- ^ 'Who doesn't go to the pictures today?', The Mail (Adelaide) Saturday 22 May 1954 Supplement: Sunday Magazine p 21

- ^ Box office figures in 1947 France at Box Office Story

- ^ a b Philip Kemp, 'On the Slide: Harry Watt and Ealing's Australian Adventure', Second Take: Australian Filmmakers Talk, Ed Geoff Burton and Raffaele Caputo, Allen & Unwin 1999 p 145-164

- ^ "Film producer in Sydney". The Sydney Morning Herald. 29 December 1944. p. 4. Retrieved 20 August 2012 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ IMDB

- ^ "The Overlanders (1946) - IMDb". IMDb.

- ^ a b "Romance on Location". The Sydney Morning Herald. 9 February 1946. p. 6. Retrieved 20 August 2012 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Late News: Australia Could Be Film-making Centre". The Sydney Morning Herald. 21 December 1945. p. 1. Retrieved 20 August 2012 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Women's News AAMWS in film role". The Sydney Morning Herald. 22 March 1945. p. 5. Retrieved 20 August 2012 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "U.S. stage offer to film actor". The Daily News (Emergency Final ed.). Perth. 22 November 1946. p. 6. Retrieved 20 August 2012 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Cast for Overlanders' passes through Broken Hill". The Barrier Miner. Broken Hill, NSW. 11 April 1945. p. 1. Retrieved 20 August 2012 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Howie-Willis, Ian (2000). "Onus, William Townsend (Bill) (1906 - 1968)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-522-84459-7. ISSN 1833-7538. OCLC 70677943. Retrieved 16 August 2021.

This article was published in hardcopy in Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 15, (Melbourne University Press), 2000

- ^ "To confer on Actors' pay". The Sydney Morning Herald. 19 November 1946. p. 3. Retrieved 19 March 2012 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Filming of cattle trek story begins". The Australian Women's Weekly. 14 April 1945. p. 16. Retrieved 20 August 2012 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Filming Great Cattle Trek For "The Overlanders"". The Sydney Morning Herald. 5 June 1945. p. 5. Retrieved 20 August 2012 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ ""Overlanders" film unit returns". The Sydney Morning Herald. 5 September 1945. p. 5. Retrieved 20 August 2012 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ a b "Stars Of "The Overlander" Had To Miss The Premiere". The Sydney Morning Herald. 28 September 1946. p. 1. Retrieved 19 August 2012 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ ""THE OVERLANDERS"". The Morning Bulletin. Rockhampton, Qld. 15 November 1946. p. 1. Retrieved 20 August 2012 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ a b c Searle, Muriel V. John Ireland - the Man and his Music. Midas Books, Tunbridge Wells, 1979, p119-121.

- ^ Stevenson, Joseph. "John Ireland: The Overlanders, film score". www.allmusic.com. Retrieved 1 September 2018.

- ^ "Watt Talks on Plans For Australian Films". The Mail. Adelaide. 21 December 1946. p. 9 Supplement: SUPPLEMENT TO "THE MAIL" MAGAZINE. Retrieved 14 February 2012 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Brian McFarlane, An Autobiography of British Cinema, Metheun 1997 p439

- ^ "New films reviewed". The Sydney Morning Herald. 30 September 1946. p. 10. Retrieved 20 August 2012 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Overlanders, The (1946). Monthly Film Bulletin, Volume 13, No.154, October 1946, page 135.

- ^ Vagg, Stephen (24 July 2019). "50 Meat Pie Westerns". Filmink.

- ^ "'Outlaw' gets past censors". The Daily News (First ed.). Perth. 15 February 1947. p. 14. Retrieved 20 August 2012 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Murphy, Robert (2003). Realism and Tinsel: Cinema and Society in Britain 1939–48. Routledge. p. 209. ISBN 978-1-134-90150-0.

- ^ "Hollywood Sneaks in 15 Films on '25 Best' List of Arty Britain". The Washington Post. 15 January 1947. p. 2.

- ^ Lant, Antonia (1991). Blackout : reinventing women for wartime British cinema. Princeton University Press. p. 232.

- ^ ""The Overlanders'" Damn Was Not For Americans". The Sydney Morning Herald. 21 December 1946. p. 3. Retrieved 20 August 2012 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "The World This Week". The Sydney Morning Herald. 1 January 1947. p. 1 Supplement: Playtime. Retrieved 20 August 2012 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Variety (September 1947)". 1947.

- ^ Pope, Quentin (30 June 1946). "British Move in on Aussie Motion Picture Making: Will Have 2 Units There Before 1947". Chicago Daily Tribune. p. e7.

- ^ "Actress Says Goodbye To Films". The Advertiser. Adelaide. 17 April 1947. p. 1. Retrieved 14 February 2012 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Umbrella Entertainment". Retrieved 4 May 2013.

- ^ Stuart, Philip. The World's Most Recorded Orchestra - The LSO Discography - August 2017 edition, entry 0216.

- ^ Searle, Muriel V. John Ireland - the Man and his Music. Chapter 12: Gramophone Records. Midas Books, Tunbridge Wells, 1979, p158.

- ^ Stuart, Philip. The World's Most Recorded Orchestra - The LSO Discography - August 2017 edition, entry 1702.

Further reading

[edit]- Atkinson, Ann; Knight, Linsay; McPhee, Margaret (1996). Arts in Australia – Theatre, Film, Radio, Television – Volume 1. Allen & Unwin Pty. Ltd.

- Harrison, Tony (1994). The Australian Film and Television Companion. Simon & Schuster Australia.

External links

[edit]- "The Overlanders". Australia: National Film and Sound Archive. Retrieved 18 May 2010.

- The Overlanders at IMDb

- The Overlanders at Australian Screen Online

- The Overlanders at BFI Screenonline

- The Overlanders at Oz Movies

- Review of film at Variety

- 1946 films

- 1946 Western (genre) films

- British Western (genre) films

- British black-and-white films

- Australian Western (genre) films

- Australian films based on actual events

- British films based on actual events

- Australian World War II films

- British World War II films

- Ealing Studios films

- Films directed by Harry Watt

- Films produced by Michael Balcon

- Films scored by John Ireland (composer)

- 1940s English-language films

- 1940s British films

- 1940s Australian films

- English-language Western (genre) films