The Long Tomorrow (novel)

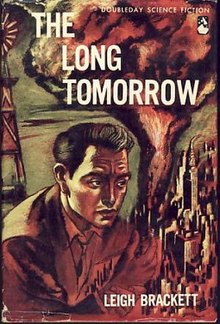

First edition | |

| Author | Leigh Brackett |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Irv Docktor |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Science fiction, post-apocalypse |

| Publisher | Doubleday |

Publication date | 1955 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | Print (hardcover & paperback) |

| Pages | 222 |

The Long Tomorrow is a post-apocalyptic science fiction novel by American writer Leigh Brackett, originally published by Doubleday & Company, Inc in 1955. Set in the aftermath of a nuclear war, it portrays a world where scientific knowledge is feared and restricted. It was nominated for a Hugo Award in 1956.

Plot summary

[edit]This article's plot summary may be too long or excessively detailed. (December 2023) |

In the aftermath of a devastating nuclear war, Americans have come to blame technology for the disaster, and far from seeking to recover what was destroyed, are actively opposed to any such attempt. Religious sects which even before the war opposed modern technology have adjusted to the post-apocalypse situation far more easily than anyone else, and have come to dominate the post-war society. All the pre-war American cities have been destroyed in the war, and their re-construction is expressly forbidden. The US Constitution has been amended, with the Thirtieth Amendment disallowing the presence of more than a thousand residents or the existence of more than two hundred buildings per square mile anywhere in the United States.

Len Colter and his cousin Esau are adolescent members of the New Mennonite community of Piper's Run. Against their fathers' wishes, the boys attend a preaching where a trader named Soames is stoned to death for his apparent involvement with a forbidden bastion of technology known as Bartorstown. They are saved when a trader, Ed Hostetter, intervenes. Hostetter grabs a box from Soames' wagon, from which Esau steals a radio. Though sickened by the stoning and harshly punished by their fathers, Len and Esau are fascinated by the idea of a community that secretly still harnesses the forbidden technologies. Len's grandmother, a little girl at the time of the destruction, sparks his interest in the technological past with her stories of big, brightly lit cities and little boxes with moving pictures.

Esau and Len begin to work the radio, trying to make 'noise' come out of it. Esau steals three books from the schoolhouse in the hope that they would teach the boys to utilise the radio. The two are punished harshly after Hostetter outs them as thieves. The radio is smashed by Esau's father in rage, and Hostetter demands his wagon be searched lest he be accused of being a member of Bartorstown. Esau is whipped and Len's father is visibly disappointed. Subsequently, Esau and Len become determined to find their way to the fabled Bartorstown and leave Piper's Run in search of it, following broken dialogue heard over the radio towards a river.

The boys make their way to a town called Refuge, living with Judge Taylor and his family and working for a warehouse owner, Mike Dulinsky. Esau starts a romantic relationship with the judge's daughter, Amity Taylor. Dulinsky wants to build a fifth warehouse to compete economically with the town on the other side of the river, Shadwell. However, this would violate the Constitution's Thirtieth Amendment as the number of buildings would exceed two hundred. He rallies the Refuge residents, who initially pledge their support, but Judge Taylor warns Len and Dulinsky of the consequences and that he would go to the state authority. The Judge eventually betrays Dulinsky to the Shadwell residents. The Shadwell residents double-cross the Judge, kill Dulinsky and set fire to Refuge.

Len, Esau and Amity are saved by Hostetter, who is revealed to be an actual member of Bartorstown. Previously, he had to out Esau as a thief to conceal his own identity. Len is let down when Hostetter's ship turns out to be a coal-powered steamship, though eventually understanding it was for concealment. Hostetter wishes to settle in a place like Piper's Run, but is unable to do so. They make a long journey to Bartorstown, a place called Fall Creek Canyon. Hostetter remarks that even those who set foot in Bartorstown do not know it is the Bartorstown, as the scientific facilities were buried, and Fall Creek Canyon resembles any ordinary settlement. Before the journey is complete, Len begins to think of Hostetter as a father-figure, the latter reciprocating that sentiment.

In Fall Creek, Amity and Esau are wed, while the three are sworn to secrecy and are told they will be shot if they attempt to leave. The town's leaders seek to use the childlike vision that Len and Esau had of Bartorstown to inspire the workers, who have been working for a long time without an end in sight. Len becomes romantically tangled with Joan Wepplo, who possesses a red dress. Joan, in contrast to Len, has resented her upbringing in Bartorstown and seeks to leave, though the residents of Bartorstown are unable to.

The scientists of Bartorstown have been working on a long-term project with an artificial intelligence, Clementine, aimed at creating a forcefield that would eradicate the splitting of atoms, preventing future misuse of nuclear technology. They feed Clementine equations in the hope of creating the ultimate equation to produce the forcefield. Len is shocked to find that Bartorstown relies on nuclear power, conflicting with his religious beliefs that the devilish nuclear power which annihilated society should be abstained from entirely. The community's rationalisation that others would eventually unlock the lost secrets of nuclear technology and that it would be better to take preventive measures does not sit well with Len and his religious upbringing.

Len and Joan, now married, plot an escape from Bartorstown, and the two succeed, blending in with tribals to evade Bartorstown's surveillance. Len's journey is painful and he thinks of the long walk back to Piper's Run as his religious redemption. However, they are tracked down by Hostetter. The three sit together in a small town where a preaching is occurring, in similar circumstances where Soames was stoned. Len mentally prepares for himself to die, thinking of Soames and Dulinsky and the disillusioned Bartorstown scientists and acknowledging that change would come around eventually, even if he as an individual passed on. Len gives up the opportunity to out Hostetter as a Bartorstown member to the crowd to be stoned, and Hostetter reciprocates by not outing Len. Hostetter is revealed to have armed backup that would have shot Len and Joan if he had outed Hostetter, but Hostetter reiterates that he knew and trusted Len so long that he never would have needed the backup. Hostetter, Len and Joan then make their way back to Bartorstown.

Critical reception

[edit]Damon Knight wrote of the novel:[1]

Unhappily, as the story progresses, it seems more and more to support Koestler's assertion that literature and science fiction cancel each other out. Most of the book, particularly the early part, is compellingly written, but not speculative... as the invented elements of the story grow more important, the vision dims... This novel illustrates a problem which science fiction writers are going to have to solve before long: how to write honestly about a mildly speculative future without dragging in pseudoscientific props by the cartload.

Writing in The New York Times, J. Francis McComas described The Long Tomorrow as "Brackett's best novel to date [and] awfully close to being a great work of science fiction". He declared that "Brackett has written a moving but always objective account of the ever-recurring clash between action and reaction in human thought and feeling".[2] Galaxy reviewer Floyd C. Gale praised the novel as a "powerful and sensitive opus".[3] In 2012 the novel was included in the Library of America two-volume boxed set American Science Fiction: Nine Classic Novels of the 1950s, edited by Gary K. Wolfe.[4] That July, io9 included the book on its list of "10 Science Fiction Novels You Pretend to Have Read".[5]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Knight, Damon (1967). In Search of Wonder. Chicago: Advent.

- ^ "In the Realm of the Spaceman", The New York Times Book Review, October 23, 1955, p.30

- ^ "Galaxy's 5 Star Shelf", Galaxy Science Fiction, March 1955, p.97

- ^ Dave Itzkoff (July 13, 2012). "Classic Sci-Fi Novels Get Futuristic Enhancements from Library of America". Arts Beat: The Culture at Large. The New York Times. Retrieved January 9, 2013.

- ^ Anders, Charlie Jane (July 10, 2012). "10 Science Fiction Novels You Pretend to Have Read (And Why You Should Actually Read Them)". io9. Archived from the original on 2014-10-14. Retrieved June 5, 2013.