The Judgement of Solomon (Poussin)

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in French. (August 2024) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

The Judgement of Solomon is an oil on canvas painting of the judgement of Solomon by the French artist Poussin, from 1649. Produced during his 1647-1649 stay in Rome, it is now in the Louvre, in Paris. It measures 101 by 150 cm. Art historians largely consider it as one of the artist masterpieces, in the art of the 17th century French School and French art as a whole. Several engravings were produced of the work.

It was commissioned by Jean Pointel, a banker from Lyon and a close friend and faithful patron of Poussin, and sent to him to display in Paris during the following months. After Pointel's death, the work passed to the financier Nicolas du Plessis-Rambouillet, then the Procureur Général to the Parliament of Paris Achille III de Harlay, and then to Charles-Antoine Hérault, a painter and a member of the Académie française. Hérault sold the work to Louis XIV in 1685 for 5000 livres.

The French royal collection initially hung it in a cabinet in the surintendance des Bâtiments, before moving it to the château de Versailles around 1710, before being seen in the salon of the directeur des Bâtiments du roi in 1784. In 1792–1793, in accordance with the principles of the Decree of 2 November 1789, the painting was seized by the revolutionary state and moved to the Louvre as one of the works displayed there when it first opened as a public museum on 10 August 1793.

History

[edit]Commission

[edit]

Towards the end of the 1640s two major figures became patrons of Poussin[1][2] The first of these was Paul Fréart de Chantelou, a friend of the artist, secretary to François Sublet de Noyers and collector of French art, whose commissions from Poussin included The Seven Sacraments and a self-portrait now in the Louvre[3][4][5] The second, Jean Pointel, was a silk merchant and banker from Lyon who had moved to rue Saint-Germain in Paris and become not only a great admirer of Poussin's work but also a friend of the artist.[6][7][8][9] Around 1645-1646 he travelled to Rome and became Poussin's friend, commissioning several works from him,[10] including The Discovery of Moses, Eliezer and Rebecca, Landscape with Polyphemus, Landscape with Orpheus and Eurydice and another self-portrait, less well-known than the one sent to Chantelou[11][3][6][7][12][13]

Pointel also owned Holy Family with Ten Figures, Noli me tangere, Landcape with Calm Weather and The Storm[11][8] and stayed in Rome again from 1647 to 1649, during which stay he commissioned the work that became Judgement.[2][10][14][15] During this productive period, Poussin also had to contend with letters from Chantelou, jealously accusing him of sending all his finer and more successful works to Pointel not Chantelou.[11][1][2][8][16][17] By contrast, the great trust between Poussin and Pointel allowed the latter to place large sums in the former's bank and he even made Pointel executor of his will, although in the end Pointel predeceased Poussin in 1660.[7][9][18][19] At the end of his life Pointel owned 21 paintings and 80 drawings by Poussin.[7][9][18]

Described as a spiritual descendant of Raphael and sometimes even as "the new Raphael", "France's Raphael" or the "French Raphael",[20][21] Poussin's Judgement was particularly influenced by Raphael's 1518-1519 treatment of the same subject[22][23] and his The Conversion of the Proconsul. In 1649, the year Judgement was completed, Poussin also produced an Assumption, Eliezer and Ebecca and his first self-portrait,[24] although around this period the Fronde made it difficult for him to contact his patrons back in France[2][25] - Oskar Bätschmann even argues from Judgement that Poussin wanted France's religious conflicts to end, with the artist superimposing an idea of justice, wisdom and equity on an emotional debate in the work.[25]

On sending Pointel Judgement around 1649-1650 Poussin called it his best work.[26][27]

Private owners

[edit]Shortly after Pointel's death, his collection was auctioned off.[18][19] According to British art historian Timothy James Clark, the executors of Pointel's will very quickly realised that they were not knowledgeable enough to assess the works and took on academician Philippe de Champaigne to catalogue and value them before putting them on the market.[28] This included Judgement and twenty other works by Poussin, but only Landscape in Calm Weather is recorded as still being in the Pointel family until 1685, with all the others sold off.[9][18][28] de Champaigne wrote of Judgement as "Item, another painting on canvas, around three feet high by four or five feet representing the Judgement of Solomon, without a frame, work by the said Poussin, taken for the sum of 800 livres".[28]

Between 1660 and 1665 it was acquired for 2200 livres by Nicolas Du Plessis-Rambouillet, financier, fermier général and secrétaire du roi - at the same time he also acquired Poussin's Landscape with a Snake for 1800 livres, also from Pointel's collection.[10][28][29] Between 1665 and 1685 the work was owned by Achille III de Harlay, Procureur Général to the Parlement de Paris from 1671 to 1689 Premier Président of the Parlement de Paris from 1689 to 1707, who hung it in his cabinet.[10][14][30][31] In 1685 Charles-Antoine Hérault was recorded as the work's owner.[14][15][32][33][34]

Royal collection

[edit]Louis XIV bought two Poussin works from Hérault for 5000 livres each in 1685,[14][15][32][33][34] one being Judgement and the other The Death of Saphira[32][35] - at other times Hérault also sold him Poussin's Madonna and Child with Saint John the Baptist, Holy Family with Saint John and Saint Elizabeth in a Landscape (also known as The Wide Holy Family) and The Shepherds of Arcadia.[34]

In 1687 Judgement was number 443 in Charles Le Brun's catalogue of the royal collection, then it was recorded in 1695 and by 1701 at the latest in the cabinet des Tableaux in the Petit Appartement du roi at the château de Versailles.[32][33] Around 1706 it was hung in the cabinet des Tableaux of the surintendance des Bâtiments, then in 1710 it returned to Versailles' cabinet des Tableaux.[32][33][36] In 1760 it was recorded in the library of the hôtel de la Surintendance, although in 1784 it was also recorded in the salon of the directeur des Bâtiments du roi with the note "It must be left wholly visible, there are five inches hidden above under the frame".[33] In 1789 Martin de la Porte was taken on to restore the 1637-1638 version of Poussin's Rape of the Sabine Women and he also worked on Judgement, with the account book stating the latter was "cleaned and [its] holes repaired" for 60 livres.[33]

State ownership

[edit]No source is known to survive showing what happened to Judgement immediately after the passing of the décret des biens du clergé mis à la disposition de la Nation on 2 November 1789 during the French Revolution.[37] That decree paved the way for royal possessions such as Judgement to be converted into 'biens nationaux' (i.e. property of the Republican and later imperial French state). It was placed in the Louvre around 1793, the year it was inaugurated as a public museum.[32][38][39] It has remained on permanent display within the museum walls ever since 1793, except for travelling exhibitions, and as of 2024 was in Room 826 of the aile Richelieu alongside six other works by the artist.[15][40]

Composition

[edit]- Studies for Judgement.

-

The background figures in this 1648-49 autograph study (now in the École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts) were dropped for the painting itself.[41]

-

Signed advanced and revised study from 1649 (now in the Louvre), with most of the figures in their final positions other than two women who were omitted in the final painting.

French poet, art critic and art historian Georges Lafenestre collaborated with Eugène Lazare Richtenberger from 1893 to 1905 to produce a catalogue raisonné of works in various European museums, including the Louvre.[36] This included producing the most factual description of Judgement possible:

Critical reception

[edit]

André Félibien noted simply and conclusively that Judgement is admirable for the correction of drawing and the beauty of expressions".[44] In an 1823 collection of works on artists' techniques and of general observations, the French medievalist and curator Alexandre Lenoir devoted a chapter to fathers' and mothers' love,[42] using Andromache, the play of the same name and the mothers in Judgement as examples of the latter:

Certainly, he knew a mother's heart as well as Racine did, this Poussin who painted the Judgement of Solomon in such an admirable manner. This work must serve as the model for all those who would wish to convey the feeling experienced by a mother who sees her infant about to be sacrificed before her eyes ; she would rather renounce her son than see him lose its life. I cite this painting, because it simultaneously conveys the tenderness of the true mother and the feelings of one who wants to seem like one without being one. Two women argue over a child : one is the mother, the other pretends to be. The affair if doubtful, how to decide it? "That the child be divided, and that a part be given to each woman" says the wise Solomon. One agrees to this, the other renounces her claim to be the mother, and gives up the child to save him from death. "That is the true mother" says the king : and the argument is ended. Painters and poets have often had cause to show maternal love carried to the last extremity by the being who is the object of that love being put in danger ; and I do not believe one may find more beautiful examples to follow of the expression of that passion, which dominates all other interests and is above all sacrifices, than in Racine and Poussin.[45]

Jean-François Sobry, author of a Poétique des arts, also praised the work:

The Judgement of Solomon by Poussin offers just as perfect details ; but it is so well-known a treatment that any educated viewer can take pleasure in devoping them for himself. Nevertheless, we observe the proud, calm and almost symmetrical pose of Solomon, seated on his throne, in the middle of the painting. Everything in it competes to show in spirit the idea of the judge's elevation, impassivity and penetration. There is nothing, not even in the lines and parallel lines or in the architecture, which does not here announce the presence of justice. And this was not the only time Poussin made the material of his composition compete with the moral effect of his painting.[46]

For the author of an article in an 1826 encyclopaedic review, Poussin was one of the greatest geniuses France has produced. He explained in these terms what - for him - made Poussin a great master of painting:

The gravity of his style, the beautiful ordering of his compositions, the truth and the variety of his various characters, are a continual subject of admiration and study. Among the works by this master in the Museum, there is one, The Judgement of Solomon, which offers to the highest degree all the kinds of merit that I have just mentioned.[47]

The French art historian, engraver and painter Charles-Paul Landon wrote that it "is impossible to render better than Poussin did the fierce joy imprinted on the livid face of the bad mother, and which appears in her commanding gesture",[48] adding that "the figures in this painting are perfectly drawn" and that "the draperies are adjusted with this noble and severe taste that Poussin drew from his study of the antique".[48] In Pierre-Marie Gault de Saint-Germain's 1806 biography of the artist he staed "we must look upon this painting as one of the greatest models of the art of imitation of impression by expression, [we] can think nothing above the characters and sentiments that animate the actors in this scene".[49] The British writer and traveller Maria Graham wrote that Judgement "is considered as one of Poussin's finest works, and perhaps no other painter has produced a better treatment of the subject", though she added that "there is not much beauty in the women, and their violent expressions excite more horror than sympathy".[50]

For François Emmanuel Toulongeon, the work "is above praise; it is even among Poussin's masterpieces, a model of sentiment, of expression, of spirit and of morality".[51] Charles de Brosses agreed and declared that it was not only one of Poussin's best paintings but also one of the best easel paintings that he knew.[52]

Mistakes

[edit]

French parliamentarian and historian François Emmanuel Toulongeon praised the work but also noted some errors and imperfections in it:

the bas-relief [on the throne] is in too Greek a style, much more modern ... [one man] is shaved; the Hebrews wore beards; this historical fault is very rare in Poussin's works ... [the half-nude] soldier is an inconvenience, especially before the king, [he is] innappropriately wearing an [ancient] Greek helmet; he is also beardless ... the child [which the soldier holds] hanging by a foot must have its belly hanging on its stomach due to its position; it is a fault of anatomy, and its foot is not felt in the soldier's hand ... there is also to the right an admiring head, whose espression is cold and filling ... Solomon's right hand is not correctly drawn ... the two hands of the woman on the right, in a blue dress, are not in the same flesh ... [and] [the background architecture], although rich, noble and wise, is too reminiscent of Greek architecture of Pericles' time[51]

Toulongeon explains his rigorous approach by admitting that "its in the first rank of paintings that one must search for and note imperfections; in others one searches for beauties".[51]

Despite praising the work, Charles-Paul Landon also noted what he held to be imperfections in it - "maybe it is [artistic] licence to represent the soldier about to strike as semi-nude, [he] more closely resembles a Greek warrior than a man guarding the king of Israel ... the tones of the draperies have no harmony with one another ... [and] the shades of the skin tones lack truthfulness".[48] Jacques Depauw notes in his article "À propos du 'Jugement de Salomon' de Poussin" that the painter made a mistake in the painting's composition.[53] In its initial paragraphs he states:

It is not rare for commentators on this painting to remark that Poussin was wrong regarding the two mothers by representing the "bad" mother with the dead child while, according to the [biblical] account of the judgement of Solomon, the "bad" mother should have with her the living child that she had substituted for her own when she realised the latter was dead. This interpretation was so established that it was mentioned in the label next to the painting at the large exhibition last winter. As soon as the "error" is pointed out we are forced to recognise that we cannot explain it. [Such a mistake] is indeed improbable if we recall the fame of this story and the seriousness with which Poussin composed his paintings.

Let us take the same subject painted by Valentin. We have no such difficulty. The dead child is at the bottom of the painting, in the middle. Above, the young Solomon, on a throne. To the left, the mother, from whose arms the executioner has just torn the child, and to the right, the other woman, came with the dead child that she has placed at the king's feet. To the softness of his face, his humble attitude, we have no hesitation - it is indeed the one who in an instant will abandon her own child to the other woman to save him from death. The arms crossed on her chest announce her prayer - "Lord, if it pleases you ...".[53]

Depauw disagrees with this premise and elaborates a theory discussed below.[53] This mistake attributed to the painter was also noted by Oskar Bätschmann, whose 1999 Dialectics of Painting stated "the painting is difficult to read since it deviates from the Biblical text and from painterly conventions".[25]

Reproductions

[edit]Prints

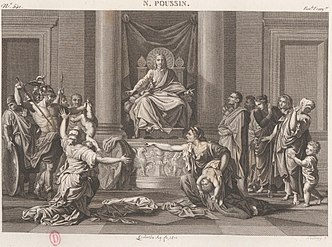

[edit]The earliest surviving print is a burin one by Jean Dughet, Poussin's brother-in-law, and dates to between 1653 and 1670. A brother of Gaspard Dughet and Anne-Marie Dughet, Jean Dughet closely collaborated with Poussin and inherited many goods from him, including his studio.[54][55] It is dedicated to Camillo Massimo.[56] Two other counter-proof prints were made but instead dedicated to an otherwise unknown Matteo Giudice.[57][58] The example of it shown below is one from these two print runs after Dughet's death in 1676, with the Medici coat of arms at the top.[57]

Guillaume Chasteau's 1685 engraving measures 37 by 52.7 centimetres and has a Latin inscription with a French translation reading "Wise Solomon invoked Nature to arbitrate his Judgement, the true mother was unable to let her son be divided. Third Book of Kings, chapter III".[59][60][61][62] The final 17th century print of the painting was one from 1691 by Martial Desbois for Charlotte-Catherine Patin's Tabellæ selectæ ac explicatæ (Paintings Chosen and Explained).[63] It is 27.8 by 39.5 cm, with two inscriptions, both in Latin, with the first in large characters translating as "The most famous of Solomon's judgements" and the second one in smaller characters stating it showed a painting by Poussin, "a Frenchman in Paris".[56][57][64]

"Engraver to the King" Étienne Gantrel produced a print of the painting measuring 46.2 by 52.5 cm around 1700.[65][66] Its French and Latin inscription exactly reproduces Chasteau's. Gantrel's version was published around 1750 by the print seller Robert Hecquet at a size of 55 by 74.5 cm[67] with a new inscription, replacing the twinned Latin and French of previous prints with a single French one reading “Wise Solomon invoked Nature to be arbitrator of his Judgement, the true mother was unable to allow her son to be divided”. Another 'engraver to the King', Étienne Baudet, also tried to make a print of the painting, but with little success.[68][69] The Baudet print in counter-proof was catalogued by Roger-Armand Weigert, qui noted that it measured 45.2 by 69 cm.[70][G 1] Baudet produced it in Rome around 1700 but we do not have a clear date for either his or Gantrel's version.[71]

In 1802 the Louvre commissioned the 22-year-old Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres to make a print of Judgement,[72][73] his first official commission.[74] Due to a dispute over money, he abandoned the project and the print, completing less than a quarter of it[75] and leaving only a pencil, brush, and wash drawing for it, now in the Louvre. Two years later, in 1804, the sixth volume of Annales du Musée et de l'École moderne des beaux-arts featured that century's first completed print after Judgement, this time by Charles Normand.[76] Another by Denis-Sébastien Leroy, Louis-Yves Queverdo and Antoine-Claude-François Villerey was published in the eighth volume of Cours historique et élémentaire de peinture, published by Filhol, Artiste-Graveur et éditeur in 1814.[77][78]

The surviving 1825 print by Antoine-Alexandre Morel is one proof before the letter, that is one of the first proofs before the caption was engraved below it by a different printing process.[79][80] A pupil of Jacques-Louis David, Morel also produced an etching in burin after the painting.[81][82] It measures 58.5 by 78.9 cm.[59][83]

| External images | |

|---|---|

The British painter and engraver Leon Kossoff produced a series of Expressionist etchings on paper after works by Poussin, known as The Poussin Project : A series of Prints after Nicolas Poussin, in collaboration with Ann Dowker.[84][85][86] Judgement is the first of them and Tate Britain and the Metropolitan Museum of Art both have two versions of it, produced in 1998, one 21.3 by 29.8 cm[87][88] and the other 42.9 by 59.7 cm.[89][90] Another version entitled From Poussin : Judgment of Solomon is now at the Annadale Galleries in Australia.[91]

- Engravings

-

Jean Dughet, 1653-1670

-

Guillaume Chasteau, 1680

-

Martial Desbois, 1691

-

Étienne Gantrel, published by Robert Hecquet, c. 1750

-

Louis-Yves Queverdo and Antoine-Claude-François Villerey, c. 1810

-

Antoine-Alexandre Morel, 1825

Other copies

[edit]A c.1649 drawing of Judgement was produced by Poussin himself almost as soon as the painting was complete and is almost identical to the painting other than the lack of clothing on the floor between the two mothers.

Very little is known of the life of French artist Denis-Sébastien Leroy, but he is known to be the artist behind a c.1800 watercolour after Judgement which notably inspired Queverdo and Villerey's print.[77][92][93] It is now in the musée Baron-Martin in Gray.[94][95][96]

Theories and analysis

[edit]The humours

[edit]

For Poussin's contemporary André Félibien, the characters in the painting are a good fit for Hippocrates's theory of the four humours and act as good visual aids for them.[98] He argued that people's complexions and skin tones demonstrated their dominant humour and that historic and contemporary painters observed this from life and depicted it. He states that in Judgement "because the true mother is in good faith, [Poussin] paints her as a simple woman without malice, whose flesh colour witnesses to the goodness of her nature; for sanguine people are not usually capable of doing ill deeds; they can be quick and choleric, but their fire soon evaporates, and they keep no hatred in their souls" whereas he "not only makes known the malice [of the bad mother] through her skin colour, but still more in her thinness and dryness caused by black bile which dominates bad people, who are hot and burning, dried out, and makes their bodies skinnier, unlike those who are a little sanguine, whose skin is fresher and firmer".[99]

Toulongeon uses similar language to describe the two women:

The bad mother's face has the more knowing expression; her red and dry eye, her flared nostrils, her toothy and gaping mouth painting her natural evil and the evil of her character; this is neither anger nor an outburst; she was born evil; her whole costume fits this; she is dirty and scruffy; she carries her dead child as if she is holding a package, uninterested, with no pain, no affection; this figure is a masterpiece of feeling and execution; she contrasts with the good mother, whose costume is simple and tidy; her head has a simple and common beauty; the two heads are both beautiful in profile".[51]

He also described the depiction of the king:

Solomon's head is the most beautiful choice if one chooses by form; he is entering adolescence, and his features already have the tranquil character of youth; his skin tone is pale and bilious, because a sanguine temperament at this age will not be susceptible to profound thoughts and reflections; his right eye squints slightly - this movement adds to his expression deciding his look towards the action.[51]

'Good' versus 'bad' mother

[edit]

In his short article in the bulletin de la Société d'étude du XVIIe siècle, Depauw reverses the usual identification of the woman on the right as the bad mother and the one on the left as the good mother, solving the artist's apparent mistake compared to the biblical account.[53] He starts from what "bothers [me] in the representation of this woman as to attributing her the role of the bad mother".[53] He notes that the woman normally understood to be the bad mother is not sympathetic to us, with a "vehement expression", "hardened features", "hair bound with a simple band", "pale skin", "rumpled clothes", "unalluring", "dull in colour". In short, she "does not correspond to our idea of the "good mother" and thus does not inspire us with the appropriate compassion".[53] By contrast, on the treatment of the bad mother (normally identified as the good mother), he writes "dressed in generous drapery in live colours, who we can guess is shapely from the little pink flesh we can see on her back, wearing a beautiful scarf, is she sympathetic to us? Maybe not so much, but she does not provoke us and as a consequence we interpret her gesture as a "Stop! Don't do that!" of protest".[53]

However, Depauw insists that this is not how the scene plays out in the biblical text - before Solomon are the woman who stole the living child, and the other woman, who firstly believed her child was dead, secondly noted that it had been substituted by another woman, and thirdly that she was persisting in wanting to keep the stolen child.[53] A dialogue of the deaf has just played out, before the king ordered the living child to be cut in half, an order a soldier is about to carry out, in the moment just before Solomon changes his mind.[53] The woman holding the dead child "is seized with an outburst and protests at the last moment, [under] the influence of anger, [born] out of a feeling of injustice".[53] Depauw continues

There is more. Let us pay attention to her pale and greenish complexion - the same as the dead child. In Valentin's painting [of the same subject], the dead child has a dead colour, but no other characters. Solomon and the two women are pink and alive. Poussin gives the good mother the skin colour of the dead child she carries. A beautiful idead by the poet-painter to represent a passion pushed to the extreme, a maternal carnal passion, and just at the moment when the fear has already entered his heart that can cause the decision in Solomon's heart that opens it up to compassion; isn't this also the complexion of the two other women in the painting, taken up, although to a lesser degree, by the same feeling? Neither the philosopher adviser who is only astonished nor evidently the bad mother have this skin tone, one which the painter conventionally lends to bodies from which life has departed.

According to this analysis, Depauw argues that this anger is at the very moment of turning into pity mixed with a feeling of terror. For him her lifted arm and pointing finger prove her to be the true mother of the child who, according to the biblical account, is about to say "My lord, if you please, give her the child; only do not kill him".[53] and is shown by Poussin at the last moment of righteous anger, about to abandon her child for love of him.[53]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Roberta Prevost (2001). Nicolas Poussin's Self-Portraits for Pointel and Chantelou. Montreal: McGill University, Department of Art History. p. 91. Retrieved 2 June 2022.

- ^ a b c d (in French) Michèle Ménard, « L’amitié de Nicolas Poussin et de Paul Fréart de Chantelou », in Foi, Fidélité, Amitié en Europe à la période moderne : Mélanges offerts à Robert Sauzet, Presses universitaires François-Rabelais, coll. « Hors Collection », 15 June 2020 ( ISBN 978-2-86906-727-1), p. 499–509

- ^ a b (in French) Horen, Guillaume (2011-04-08). "Paul Fréart de Chantelou (1609-1694)". Nicolas Poussin, peintre classique du 17e siècle. Retrieved 2022-06-02.

- ^ (in French) "Autoportrait - Petite Galerie - musée du Louvre". petitegalerie.louvre.fr. Retrieved 2022-06-02.

- ^ (in French) Poussin, Nicolas. "Autoportrait, 1650". Retrieved 2022-06-02.

- ^ a b (in French) Paul Desjardins (1903). Les Grands Artistes - Poussin. Collection d'enseignement et de vulgarisation. France: Henri Laurens Éditeur. p. 72. Retrieved 2 June 2022.

- ^ a b c d (in French) Horen, Guillaume (2011-04-08). "Jean Pointel". Nicolas Poussin, peintre classique du 17e siècle. Retrieved 2022-06-02..

- ^ a b c (in French) Louis-Firmin-Hervé Bouchitté (1858). Le Poussin, Sa vie et son oeuvre, Suivi d'une notice sur la vie et les ouvrages de Philippe de Champaigne et de Champagne le neveu. Paris: Didier et Cie, Libraires-Éditeurs. pp. 66–67, 173–178. Retrieved 2 June 2022.

- ^ a b c d (in French) "Nicolas Poussin. Paysage par temps calme (1651)". rivagedeboheme.fr. Retrieved 2022-06-05..

- ^ a b c d (in French) Edmond Bonnaffé (1884). Dictionnaire des amateurs français au XVIIe siècle. Paris: A. Quantin, Imprimeur-Éditeur. pp. 95, 134, 257. Retrieved 2 June 2022.

- ^ a b c L[ouis] Poillon (1868). Nicolas Poussin - étude biographique (1 ed.). Lille ; Paris: J. Lefort. pp. 97–99, 109.

- ^ "The artist has a preference". Self-Portrait of the Artist. 2013-03-10. Retrieved 2022-06-02..

- ^ (in French) Pierre Rosenberg et Louis-Antoine Prat, Nicolas Poussin 1594-1665, Paris, Réunion des musées nationaux, 1994, page 425-427

- ^ a b c d (in French) Thérèse Bertin-Mourot (1949). Société Poussin & Musée du Louvre (ed.). Nicolas Poussin : peintures, dessins et gravures : exposition, Paris, Bibliothèque nationale. Paris. p. 20. Retrieved 2 June 2022.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d (in French) "Le jugement de Salomon". pop.culture.gouv.fr. Retrieved 2022-06-03.

- ^ (in French) Poussin, Nicolas (1647). "Moïse sauvé des eaux". Retrieved 2022-06-03.

- ^ (in French) Nicolas Poussin; Charles Jouanny (1911). Correspondance de Nicolas Poussin, publiée d'après les originaux. Paris: Jean Shemit, libraire de la Société de l'histoire de l'art français. pp. 371–375. Retrieved 2 June 2022.

- ^ a b c d (in French) "Nicolas Poussin. Paysage par temps calme (1651)". rivagedeboheme.fr. Retrieved 2022-06-02..

- ^ a b "Nicolas Poussin. Les tableaux du Louvre (extrait) by Somogy éditions d'Art - Issuu". issuu.com. 18 August 2015. Retrieved 2022-06-02..

- ^ (in French) "Dix choses que vous ne saviez pas sur Poussin". Geo.fr. 2018-08-11.

- ^ (in French) "LA FRANCE PITTORESQUE - 19 novembre 1665 : mort du peintre Nicolas Poussin à Rome". La France pittoresque. Histoire de France, Patrimoine, Tourisme, Gastronomie. 2012-11-17..

- ^ Cummings, Frederick (1962). "Poussin, Haydon, and The Judgement of Solomon". The Burlington Magazine. 104 (709): 146–155. JSTOR 873616. Retrieved 2022-06-05.

- ^ Hoakley (2016-07-28). "The Story in Paintings: The judgement of Solomon". The Eclectic Light Company..

- ^ (in French) Pierre Rosenberg and Louis-Antoine Prat, Nicolas Poussin 1594-1665, Paris, Réunion des musées nationaux, 1994, p. 416-417.

- ^ a b c Oskar Bätschmann (1999). Nicolas Poussin - Dialectics of Painting. United Kingdom: Reaktion Books Ltd. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-948462-43-6. Retrieved 5 June 2022.

- ^ (in Italian) Giovanni Pietro Bellori, Vite dei pittori, scultori ed architetti moderni descritte da Gio. Pietro Bellori: Tomo II, Pisa, Presso Niccolò Capurro, 1821, pages 197-198

- ^ (in French) "Le Jugement de Salomon, peint par Poussin, huile sur toile de 1649". Nicolas Poussin, peintre classique du 17e siècle. 2013-02-24. Retrieved 2022-06-02.

- ^ a b c d Timothy James Clark (2008). The Sight of Death: An Experiment in Art Writing. USA: Yale University Press. pp. 69–79. ISBN 978-0300117264.

- ^ (in French) Isabelle Richefort (1998). Peintre à Paris au XVIIe siècle. France: Éditions Imago. pp. Note 15.

- ^ (in French) "POUSSIN Nicolas : LE JUGEMENT DE SALOMON". devoir-de-philosophie.com..

- ^ (in French) André Félibien, Entretiens sur les vies et sur les ouvrages des plus excellens peintres anciens et modernes, volume IV. Paris: S. Marbre-Cramoisy. 1666–1688. p. 99.

- ^ a b c d e f "Catalogue entry". 1649.

- ^ a b c d e f (in French) Nicolas Bailly; Fernand Engerand (1899). Inventaire des tableaux du roy : inventaires des collections de la Couronne - rédigé en 1709 et 1710 par Nicolas Bailly ; publié pour la première fois, avec des additions et des notes, par Fernand Engerand. Paris: Ernest Leroux, Éditeur. pp. 304–306.

- ^ a b c Pierre Rosenberg; Louis-Antoine Prat (1994). Nicolas Poussin 1594-1665. Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux. pp. 416–417. ISBN 978-2-7118-3027-5.

- ^ (in French) "Catalogue entry". 1653.

- ^ a b (in French) Georges Lafenestre (1893–1905). La Peinture en Europe - Catalogues raisonnés des œuvres principales conservées dans les musées, collections, édifices civils et religieux - Le musée national du Louvre. Paris: Ancienne Maison Quantin, Librairies-Imprimeurs Réunies. p. 252.

- ^ (in French) Émile Laurent; Jérôme Mavidal, eds. (1877). "« Motion de M. de Talleyrand sur les biens ecclésiastiques, lors de la séance du 10 octobre 1789 », in Archives Parlementaires de 1787 à 1860, volume IX". Archives Parlementaires de la Révolution Française. 9 (1). Paris: Librairie Administrative P. Dupont: 398–404.

- ^ (in French) Musée du Louvre (1793). Catalogue des objets contenus dans la Galerie du Muséum français : décrété par la Convention nationale, le 27 juillet 1793 l'an second de la République française. Paris: Imprimerie de C.-F. Patris, imprimeur du Musée national. p. 9.

- ^ (in French) Société de l'histoire de l'art français (1909). Archives de l'art français - Recueil de documents inédits - Nouvelle période - Tome III. Paris: Jean Schemit, Libraire de la Société de l'histoire de l'art français. p. 381.

- ^ (in French) "Catalogue entry". collections.louvre.fr..

- ^ "Spencer Alley: Anthony Blunt on Nicolas Poussin - Old Testament (II)". Spencer Alley. 2021-02-25.

- ^ a b Alexandre Lenoir (1823). La Vraie science des artistes, ou Recueil de préceptes et d'observations , formant un corps complet de doctrine, sur les arts dépendans du dessin. Paris: B. Mondor, Éditeur des Annales françaises. pp. 195–196.

- ^ (in French)Mathieu-Guillaume-Thérèse Villenave, Les Métamorphoses d'Ovide, traduction nouvelle - Tome Quatrième, Imprimerie de P. Didot l'Aîné, 1906, Paris, p. 118–119.

- ^ André Félibien (1666–1688). Entretiens sur les vies et sur les ouvrages des plus excellens peintres anciens et modernes. Vol. IV. Paris: S. Marbre-Cramoisy. pp. 59–60.

- ^ (in French) Lenoir, Alexandre (1823). La Vraie science des artistes, ou Recueil de préceptes et d'observations , formant un corps complet de doctrine, sur les arts dépendans du dessin. Paris: B. Mondor, Éditeur des Annales françaises. pp. 195–196.

- ^ (in French) Jean-François Sobry (1810). Poétique des arts, ou Cours de peinture et de littérature comparées. Paris: Delaunay, Brunot-Labbé et Colnet, Libraires. pp. 188–189.

- ^ (in French) Members of the Office of the revue encyclopédique (1826). Revue encyclopédique, ou Analyse raisonnée des productions les plus remarquables dans la littérature, les sciences et les arts - Volume 29. France: Bureau de la revue encyclopédique. p. 341.

- ^ a b c (in French) Charles-Paul Landon (1804). Annales du musée et de l'école moderne des beaux-arts. France: Imprimerie des Annales du Musée. pp. 136–138.

- ^ (in French) Pierre-Marie Gault de Saint-Germain (1806). A.A. Renouard (ed.). Vie de Nicolas Poussin - considéré comme chef de l'école française, suivie de notes inédites et authentiques sur sa vie et ses ouvrages, des mesures de la statue de l'Antinous, de la description de ses principaux tableaux, et du catalogue de ses œuvres complétes. Paris: A.A. Renouard. p. 51.

- ^ (in French) Maria Graham (1821). Mémoires sur la vie de Nicolas Poussin. France: Pierre Dufart, Libraire. p. 151.

- ^ a b c d e (in French) François Emmanuel Toulongeon (1802). Manuel du muséum français , avec une description analytique et raisonnée de chaque tableau indiqué au trait par une gravure à l'eau-forte, tous classés par écoles et par oeuvre des grands artistes. Paris: Treuttel et Würtz, Libraires. pp. 13–17.

- ^ (in French) Charles de Brosses (1798). Lettres historiques et critiques sur l'Italie, de Charles de Brosses - Avec des notes relatives à la situation actuelle de l'Italie, et la liste raisonnée des Tableaux et autres Monuments qui ont été apportés à Paris, de Milan, de Rome, de Venise, etc. - Tome Second. Paris: Ponthieu, Libraire. pp. 399–401.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Jacques Depauw (April 1996). "À propos du Jugement de Salomon de Poussin". XVIIe siècle : Bulletin de la Société d'étude du XVIIe siècle. 191 (2): 241–245.

- ^ (in French) Chennevières-Pointel, Charles-Philippe de (1894). Essais sur l'histoire de la peinture française / Ph. de Chennevières.

- ^ (in French) Robarts, Pierre François (1865). Catoloque général des ventes publiques de tableaux et estampes depuis 1737 jusqu'à nos jours. Contenant: 1. Les prix des plus beaux tableaux, dessins, miniatures, estampes, ouvrages à figures et livres sur les arts. 2. Des notes biographiques, formant un dictionnaire des peinters et des graveurs les plus célèbres de toutes les écoles. Paris Aubry.

- ^ a b (in French) Weigert, Roger-Armand (1954). Inventaire du fonds français, graveurs du XVIIe siècle. Tome III, Chauvel-Duvivier / Bibliothèque nationale, cabinet des estampes. France: Chauvel - Duvivier, Bibliothèque nationale de France. pp. 411, 519.

- ^ a b c (in French) Wildenstein, Georges (1957). Les graveurs de Poussin au XVIIe siècle / par Georges Wildenstein ; introduction par Julien Cain.

- ^ (in French) Dughet; Nicolas Poussin. Jugement de Salomon (Le).

- ^ a b (in German) Andresen, Andreas (1863). Nicolaus Poussin.

- ^ (in French)"Gravures de l'oeuvre de Poussin". Nicolas Poussin, peintre classique du 17e siècle. 14 October 2021.

- ^ (in French) Bibliothèque nationale (France) Département des estampes et de la photographie (1951). Inventaire du fonds français, graveurs du XVIIe siècle. Tome II, Boulanger (Jean)-Chauveau (François) / Bibliothèque nationale, Département des estampes ; [réd.] par Roger-Armand Weigert,... Retrieved 2022-07-13.

- ^ (in French) Chavignerie, Émile Bellier de La (1882). Dictionnaire général des artistes de l'école française depuis l'origine des arts du dessin jusqu'à nos jours. Renouard.

- ^ (in French) Patin, Charlotte-Catherine (1691). Tabellae selectae ac explicatae. Patavii, Ex Typographia Seminarii. pp. 15–16. Retrieved 2022-07-13.

- ^ Alexandre-Pierre-François Robert-Dumesnil; Georges Duplessis (1835–1871). Le peintre-graveur français, ou Catalogue raisonné des estampes gravées par les peintres et les dessinateurs de l'école française : ouvrage faisant suite au Peintre-graveur de M. Bartsch. Tome 4 / par A.-P.-F. Robert-Dumesnil (in French).

- ^ (in French) Bibliothèque nationale (France) Département des estampes et de la photographie (1961). Inventaire du fonds français, graveurs du XVIIe siècle. Tome IV, Ecman-Giffart / Bibliothèque nationale, Cabinet des estampes ; [réd.] par Roger-Armand Weigert.

- ^ (in French) "Le jugement de Salomon". numelyo..

- ^ (in French) "Catalogue entry".

- ^ "Collections Online - British Museum". britishmuseum.org..

- ^ (in French) Revue universelle des arts. Revue. 1858.

- ^ (in French) Bibliothèque nationale (France) Département des estampes et de la photographie (1939). Inventaire du fonds français, graveurs du XVIIe siècle. Tome premier, Alix (Jean)-Boudeau (Jean) / Bibliothèque nationale, Département des estampes ; [réd.] par Roger-Armand Weigert,...

- ^ (in French) Remi Porcher (1885). Étienne Baudet, graveur du Roi (1638-1711), par R. Porcher,... 2e édition. Edition 2.

- ^ (in French) Dictionnaire de la peinture ([Nouv. éd.]) / sous la dir. de Michel Laclotte et Jean-Pierre Cuzin ; avec la collab. d'Arnauld Pierre. 2003.

- ^ "Catalogue entry". 1802.

- ^ (in French) La Revue de Paris. Bureau de la Revue de Paris. 1909.

- ^ (in French) La Nouvelle revue. Progrès. 1909.

- ^ (in French) Landon, Charles Paul (1804). Annales du musée et de l'école moderne des beaux-arts...: Pictures. Sculpture. Architecture, 1800-08. 16 v. C. P. Landon.

- ^ a b "print - British Museum". The British Museum..

- ^ (in French) Nouvelles de l'estampe. Comité national de la gravure française. 2006.

- ^ "Dictionnaire Technique de l'estampe par André Béguin". presse-estampe.com..

- ^ "avant la lettre - Définition de l'expression - Dictionnaire Orthodidacte". dictionnaire.orthodidacte.com..

- ^ (in French) Roger baron Portalis; Henri Béraldi (1882). Les graveurs du dix-huitième siècle. D. Morgand et C. Fatout.

- ^ (in French) Jean Duchesne (1855). Description des estampes exposées dans la Galerie de la Bibliothèque Impériale, formant un aperçu historique des productions de l'art de la gravure. Imprimérie Simon Raçon.

- ^ "Catalogue entry". Gallica. 1825.

- ^ Tate. "'From Poussin: The Judgement of Solomon', Leon Kossoff, 2000". Tate.

- ^ L.A. Louver (galerie d'art). "Leon Kossoff - Biography" (PDF). lalouver.com..

- ^ "Poussin Landscapes by Kossoff". lalouver.com..

- ^ "Catalogue entry". Tate Britain.

- ^ "Catalogue entry". Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ^ "Catalogue entry". Tate Britain.

- ^ "Catalogue entry". Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ^ "Catalogue entry". annandalegalleries.com.au..

- ^ "Collections Online - British Museum"..

- ^ (in French) Harvard University (1865). Guide théorique et pratique de l'amateur de tableaux. Vve. Jules Renouard.

- ^ (in French) Nicolas Poussin : 1594-1665 : Galeries nationales du Grand Palais, 27 septembre 1994-2 janvier 1995. Paris : Réunion des musées nationaux. 1994. ISBN 978-2-7118-3027-5.

- ^ (in French) Catalogue d'une belle collection aquarelles et dessins des écoles anglaise et française par Bentley, Bonington, Boys, Callow Copley, Frédéric et Newton Fielding, Harding, Prout, C. Stanfield, H. Bellangé, de Boissieu, Charlet, Dauzats, Decamps, E. Delacroix, Géricault, Girodet, Granet, Grenier, Gué, Mme Haudebourt-Lescot, Eugène Isabey, Alfred Johannot, Nicolle, Prud'hon, Robert-Fleury, Camille Roqueplan, Ary Scheffer, Siméon-Fort, Horace Fernet, Wille, etc. Beau tableau par Sébastien Vrancx et Jean Brueghel le Jeune. Beaux bronzes des époques Louis XIV, Louis XV et Louis XVI. Coffret du XVIe siècle en argent, ivoires, porcelaines de Chine et autres. Grands vases Louis XVI en albatre orientale, montés en bronze doré. Bronzes d'ameublement, meubles en bois sculpté et en marqueterie. Objets variés. Dépendant de la succession de M. Charles Turpin... Provenant du chateau de Villetard, près Blois. Renou, Maulde et Cock. 1874.

- ^ (in French) Rosenberg, Pierre; Poussin, Nicolas; Prat, Louis-Antoine (1994). Nicolas Poussin : 1594-1665 : Galeries nationales du Grand Palais, 27 septembre 1994-2 janvier 1995. Réunion des musées nationaux. p. 86. ISBN 978-2-7118-3027-5.

- ^ (in French) "Early Medicine and Physiology". webspace.ship.edu..

- ^ (in French) André Félibien, Entretiens sur les vies et sur les ouvrages des plus excellens peintres anciens et modernes, volume IV, Paris, S. Marbre-Cramoisy, 1666-1688, pages 341 to 343.

- ^ (in French) André Félibien, Entretiens sur les vies et sur les ouvrages des plus excellens peintres anciens et modernes, volume IV, Paris, S. Marbre-Cramoisy, 1666-1688, pages 341-343.

- ^ Étienne Baudet, Le Jugement de Salomon, d'après Nicolas Poussin, vers 1700, gravure, 45,2 x69 centimètres.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bellori, Giovanni Pietro (1821). Presso Niccolò Capurro (ed.). Vite dei pittori, scultori ed architetti moderni descritte da Gio. Pietro Bellori: Tomo II (in Italian). Pise. pp. 145–207.

- Jacques Thuillier (1974). Groupe Flammarion (ed.). Toute l'œuvre de Poussin. Paris.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Jacques Thuillier; Claude Mignot (1978). Revue de l'Art (ed.). Collectionneur et peintre au XVIIe : Pointel et Poussin. France. pp. 50–51.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Jacques Thuillier (1994). Groupe Flammarion (ed.). Nicolas Poussin. Paris. pp. 121–135, 203–204.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Nicolas Milovanovic (2021). Editions Gallimard / Musée du Louvre Editions (ed.). Peintures françaises du XVIIe du musée du Louvre. France.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Olivier Bonfait (2015). Hazan (ed.). Poussin et Louis XIV: Peinture et Monarchie dans la France du Grand Siècle. Paris.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Musée du Louvre (2015). Hazan/ Louvre éditions (ed.). Poussin et Dieu. Paris.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Pierre Rosenberg (2015). Louvre éditions/ Somogy (ed.). Nicolas Poussin : les tableaux du Louvre. Paris. pp. 210–215.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Pierre Rosenberg; Louis-Antoine Prat (1994). Réunion des musées nationaux (ed.). Nicolas Poussin 1594-1665. Paris. pp. 416–417. ISBN 978-2-7118-3027-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Pierre Rosenberg (2015). The Burlington Magazine (ed.). Poussin and God. États-Unis. pp. 561–563.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Matthieu Lett (2014). Presses universitaires (ed.). « Les tableaux du Petit Appartement de Louis XIV à Versailles », dans Louis XIV, l'image et le mythe, actes du colloques. Rennes. p. 125.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Drago, ed. (2011). Poussin et Moïse. Du dessin à la tapisserie, 1. Rome.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Drago, ed. (2011). Poussin et Moïse. Du dessin à la tapisserie, 2. Rome. p. 84.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Marie-Martine Dubreuil (2001). Bulletin de la Société de l’histoire de l’art français (ed.). Le catalogue du Muséum Français (Louvre) en 1793. Etude critique. France. pp. 125–165.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Paul Fréart de Chantelou (2001). Macula (ed.). Journal de voyage du cavalier Bernin en France. France. p. 181.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Maurizio Fagiolo dell'Arco (1996). Ugo Bozzi (ed.). Jean Lemaire pittore antiquario (in Italian). Rome. p. 80.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Stéphane Loire (1989). Réunion des musées nationaux (ed.). Musée du Louvre. Peintures françaises. XIV-XVII. Guide de visite. Paris. pp. 58–59.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Isabelle Compin; Anne Roquebert (1986). Réunion des musées nationaux (ed.). Catalogue sommaire illustré des peintures du musée du Louvre et du musée d'Orsay. IV. Ecole française, L-Z. Paris. p. 142.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Isabelle Compin; Nicole Reynaud; Pierre Rosenberg (1974). Musées nationaux (ed.). Musée du Louvre. Catalogue illustré des peintures. Ecole française. XVII-XVIII : II, M-Z. Paris. p. 60.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Isabelle Compin; Nicole Reynaud (1972). Réunion des musées nationaux (ed.). Catalogue des peintures du musée du Louvre. I, Ecole française. Paris. p. 300.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Rudolf Wittkower (1963). Princeton University Press (ed.). The Role of Classical Models in Bernini's and Poussin's Preparatory », dans Studies in Western Art, Latin American Art and The Baroque Period in Europe, actes du colloque. New York. pp. 41–50.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Gaston Brière (1924). Musées nationaux (ed.). Musée national du Louvre. Catalogue des peintures exposées dans les galeries. I.Ecole française. Paris. p. 204.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - André Félibien (1666–1688). S. Marbre-Cramoisy (ed.). Entretiens sur les vies et sur les ouvrages des plus excellens peintres anciens et modernes, tome IV. Paris. pp. 59–60, 99, 341–343.

- Guy de Compiègne (2015). Le point de vue chez Nicolas Poussin (PDF).

Exhibitions

[edit]It appeared in a touring exhibition from 1994 to 1995, staged at the Galeries nationales du Grand Palais in Paris (27 September 1994 to 2 January 1995) and the Royal Academy in London (19 January to 13 April 1995).

![The background figures in this 1648-49 autograph study (now in the École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts) were dropped for the painting itself.[41]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/93/%C3%89tude_du_Jugement_de_Salomon%2C_entre_1648_et_1649.jpg/225px-%C3%89tude_du_Jugement_de_Salomon%2C_entre_1648_et_1649.jpg)