The Face in the Frost

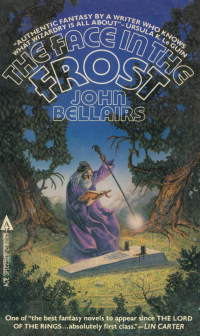

Third Ace Books paperback edition (1981) with cover illustration by Carl Lundgren | |

| Author | John Bellairs |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | Marilyn Fitschen |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Fantasy |

| Publisher | Macmillan Publishers |

Publication date | 17 February 1969 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | Print (Hardback) |

| Pages | ix, 174 |

| ISBN | 0-441-22529-2 |

| OCLC | 21238446 |

The Face in the Frost is a short fantasy novel by American author John Bellairs published in 1969.[1] Unlike most of his later works, this book is meant for adult readers. It centers on two accomplished wizards, Prospero ("and not the one you're thinking of") and Roger Bacon, tracking down the source of a great magical evil. The subject matter prompted Ursula K. Le Guin to say of the novel,

- "The Face in the Frost takes us into pure nightmare before we know it—and out the other side."

This novel was listed in the "recommended reading" list in the first edition Advanced Dungeons and Dragons Dungeon Master's Guide by Gary Gygax. Although being listed, it was not an influence on the formation of the game. In a review of the book by Gygax in Dragon magazine, issue 22, he states,

- "As I have not read the book until recently, there is likewise no question of it influencing the game. Nonetheless, The Face in the Frost could have been a prime mover of the underlying spirit of D&D."[2]

Plot

[edit]The story opens with Prospero at home on a late summer day when he feels particularly uneasy. In the evening he receives an unexpected visit from his friend Roger Bacon, and the two discuss unusual phenomena that have transpired lately, especially those concerning a mysterious book for which Roger has been searching England. The following morning the two wizards find Prospero’s house besieged by agents of some other wizard who seems to have ill designs for them. They escape the house by shrinking themselves down and sailing out on a model ship via an underground stream accessible through Prospero’s basement. Once they regain their normal size they visit a library of records where Prospero discovers, as Roger stands guard outside, that a seal appearing in the mysterious aforementioned book belongs to Melichus, an old rival of his. Unfortunately, at that point a person comes into the library and claims to have killed Roger.

Prospero flees the library and spends the night in a nearby town, where he luckily escapes an attack from some sort of evil creature sent by Melichus. The following day he travels to the cursed grove where Melichus is supposed to be buried, only to discover that the one buried there is not Melichus, but only one of his former servants. He presumes, therefore, that Melichus is still alive. After narrowly escaping from the cursed grove he travels to the town of Five Dials, where he stays at an inn with somewhat unsettling clientele and staff. Unable to sleep, he becomes suspicious of the inn and begins checking the other rooms, only to find them all empty. In the last room he finds the innkeeper with a large knife and flees the inn, whereupon he discovers that the entire town was an illusion (presumably created by Melichus).

At last, Prospero and Roger are reunited at the actual site called Five Dials, a lone inn on the edge of the country. Here they discuss why Melichus is after Prospero: they once created a magical item together, a kind of crystal ball resembling a green glass paperweight. Since neither one can fully possess it without the other’s cooperation, Prospero will have some share in Melichus’ power until he is dead. They also determine that Melichus is using the mysterious book mentioned early in the story to create a permanent winter over the world. While staying the night at Five Dials they meet a small armed force that intends to attack a village across the border. Roger and Prospero thwart the army by destroying a necessary bridge and begin traveling to the village where the paperweight is kept, and where, they presume, Melichus is now. As they travel, unseasonably cold weather gradually sets in. Though the way to their destination is blocked, they find a monk herbalist who lets them in through a back entrance. Once in the village they do find Melichus studying the book. Prospero attempts to steal the paperweight, only to be transported to a different world. Melichus follows him there, but Prospero meets another wizard who takes the magical item and defeats Melichus. In the end, Prospero returns home to find that the early winter has subsided.

The novel closes with a victory celebration of the wizards involved in vanquishing Melichus and destroying the book Melichus used.

Critical reception

[edit]The novel was well-reviewed upon its initial release. Lin Carter praised it as one of only three best fantasy novels to be published since The Lord of the Rings.[3] Ursula Le Guin described it as an

- "authentic fantasy by a writer who knows what wizardry is all about."

She also praised the skill with which Bellairs navigated between humor and darker elements.

Since its publication, the book has continued to receive acclaim, both from within the fantasy community[4] and from the mainstream media. John Clute echoes Le Guin's praise of the novel's balance between humor and darker content, and praises it as "a unique classic".[5] Literary critic Michael Dirda has praised the novel as "fine adult fantasy".[6]

Further adventures

[edit]Lin Carter said that during their correspondence, Bellairs had shared with him

- “sketchy maps of the South Kingdom and some unpublished scraps, notes, and outlines for ... further adventures”

and that Bellairs had also produced a prequel, “which tells how his diabolic duo first became friends”.[7] The prequel piece was to be included in Carter’s juvenile fantasy anthology Magic Kingdoms, but that anthology was never published and Bellairs' short story is presumed lost.

In early 1980, Bellairs shared with author Ellen Kushner an unfinished manuscript for a sequel to The Face in the Frost entitled The Dolphin Cross. Over the years Kushner urged Bellairs to complete the story – in which Prospero is mysteriously kidnapped to a solitary island – but Bellairs instead focused his attention on his successful young adult adventures.[8] The unfinished manuscript survived and The Dolphin Cross was included in the 2009 anthology Magic Mirrors, which was published by the New England Science Fiction Association press.

References

[edit]- ^ Catalog of Copyright Entries. Third Series: 1969: January-June. Copyright Office, Library of Congress. 1972. p. 117.

- ^ Gygax, E. Gary; Cur, Mike; Minch, Dave (1979). "Reviews". Dragon. Vol. III, no. 8. p. 15. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- ^ Carter, Lin, ed. (1973). Imaginary Worlds. New York, NY: Ballantine. pp. 165–167. ISBN 978-0-34503309-3.

- ^ Tymn, Marshall B.; Zahorski, Kenneth J.; Boyer, Robert H., eds. (1979). Fantasy Literature: A core collection and reference guide. New York, NY: R.R. Bowker Co. p. 51. ISBN 0-8352-1431-1.

- ^ Clute, John; Grant, John, eds. (1997). "Bellairs, John". The Encyclopedia of Fantasy. pp. 103–104. ISBN 978-1-85723-368-1. OCLC 37106061.

- ^ Dirda, M. (19 January 2000). "Dirda on books". Washington Post. Dirda 119. Retrieved 9 August 2014 – via WashingtonPost.com.

- ^ Carter, L. (1973). Imaginary Worlds. New York, NY: Ballantine Books / Random House. — book cites Carter's correspondence with Bellairs

- ^ Kushner, E. (2009). "John and Me". Magic Mirrors. NESFA Press.