The 20th-Century Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

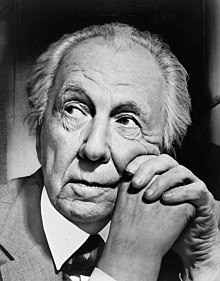

Frank Lloyd Wright, the architect whose buildings are designated as a World Heritage Site | |

| Includes | Eight locations in the United States |

| Criteria | Cultural: (ii) |

| Reference | 1496 |

| Inscription | 2019 (43rd Session) |

| Area | 26.369 ha (65.16 acres) |

| Buffer zone | 710.103 ha (1,754.70 acres) |

The 20th-Century Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright is a UNESCO World Heritage Site consisting of eight buildings across the United States designed by American architect Frank Lloyd Wright.[1][2] These sites demonstrate his philosophy of organic architecture, designing structures that were in harmony with humanity and its environment. Wright's work had an international influence on the development of architecture in the 20th century.[3]

Background

[edit]The architect Frank Lloyd Wright (1867–1959) was raised in rural Wisconsin and studied civil engineering at the University of Wisconsin. He then apprenticed with noted architects in the Chicago school of architecture, particularly Louis Sullivan. Wright opened his own practice in Chicago in 1893, and developed a home and studio in Oak Park, Illinois. In the 20th century, he became a world-renowned architect.[4][5]

Through efforts led by the Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy, a nonprofit organization, Taliesin and Taliesin West were jointly nominated as a World Heritage Site in the late 1980s.[6] The U.S. federal government endorsed the nomination,[7] but UNESCO rejected it because the organization wanted to see a larger nomination with more Wright properties.[6] In 2008, the National Park Service submitted ten Frank Lloyd Wright properties to a tentative World Heritage list.[8][9] It grew to 11 structures across seven U.S. states in July 2011.[10][11] The nominated buildings included two of Wright's studios; two office buildings; four private residences; and one museum, church, and government building each.[10][12] The S. C. Johnson & Son Inc. Administration Building and Research Tower in Racine, Wisconsin, was later removed from the nomination.[13][14]

In March 2015, the United States Department of the Interior again nominated ten Wright–designed structures for inclusion on the World Heritage List.[13][15][16] UNESCO declined to designate Wright's buildings in July 2016, referring the nomination back to the Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy for revision.[17][18] The Conservancy–led Frank Lloyd Wright World Heritage Council collaborated with the National Park Service and UNESCO to modify the nomination.[19] Eight of Wright's buildings were re-nominated to the World Heritage List in December 2018;[20][21] the Price Tower in Bartlesville, Oklahoma, and the Marin County Civic Center in San Rafael, California, were excluded from the proposal.[19] The following June, the International Council on Monuments and Sites recommended the nomination's approval.[22] The site was inscribed on the World Heritage list on July 7, 2019.[23] It was the 24th World Heritage listing in the United States to be designated,[1][2][24] and it was the first time that modern American architecture had been recognized by UNESCO.[25]

World Heritage listing

[edit]The eight Wright buildings in the World Heritage Site are located in six U.S. states and were designed over a 50-year period.[2] The first building included, Unity Temple, was completed in 1908.[1] The last, the Guggenheim Museum, was completed in 1959,[1][2] although its design began in the 1940s.[26] All eight buildings are also listed as U.S. National Historic Landmarks.[16][27] These structures were nominated because, out of all of Wright's buildings, they were deemed "his masterpieces with the highest levels of integrity".[28]

| Picture | ID[29] | Name | Location | Description | Coordinates | Property Area [Buffer Zone] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1496rev-001 | Unity Temple | Oak Park, Illinois | Completed in 1908, this unprecedented church building used reinforced concrete in novel ways, creating a light-filled space with natural features. Its use of this single material has caused it to be thought of as the first "modern building" in the world.[30] | 41°53′18″N 87°47′48″W / 41.88833°N 87.79667°W | 0.167 ha (0.41 acres) [10.067 ha (24.88 acres)] |

|

1496rev-002 | Frederick C. Robie House | Chicago, Illinois | This 1910 single-family home is considered a masterpiece of the Prairie School of architecture. Its "broad, sweeping horizontal lines; low, cantilevered roofs with overhanging eaves; and an open interior floor plan, . . . epitomizes Wright’s aim to design structures in harmony with nature."[31] A significant contributor to the concept of bringing nature indoors is the 175 leaded glass windows and doors, which feature a design of "abstraction of organic shapes".[32] | 41°47′23.4″N 87°35′45.3″W / 41.789833°N 87.595917°W | 0.130 ha (0.32 acres) [1.315 ha (3.25 acres)] |

|

1496rev-003 | Taliesin | Spring Green, Wisconsin | Begun in 1911 and expanded several times over the years,[33] Taliesin (Welsh for 'shining brow') became Wright's home, studio, and school of architecture. He built the large estate on the brow of a ridge, to be "'of the hill' not on it".[34] It may be his most expansive and longest exploration of the organic theory of architecture and the Prairie School.[34] | 43°08′30″N 90°04′15″W / 43.14153°N 90.07091°W | 4.931 ha (12.18 acres) [200.899 ha (496.43 acres)] |

|

1496rev-004 | Hollyhock House | Los Angeles, California | Wright's first commission in Los Angeles, Hollyhock House (built 1918–1921) was intended to be part of an arts colony and live theater complex in East Hollywood, built when the Southern California movie business was taking off. The work of Wright and his young apprentices became a springboard to what became known as California Modernism.[35] The structure's outdoor gardens and interior spaces are integrated.[36] | 34°05′59.85″N 118°17′40.61″W / 34.0999583°N 118.2946139°W | 4.608 ha (11.39 acres) [13.986 ha (34.56 acres)] |

|

1496rev-005 | Fallingwater | Stewart Township, Pennsylvania | Built as a summer home in 1935, Fallingwater epitomizes Wright's ideas of organic architecture. Placed over a stream and waterfall, its cantilevered terraces of rock and geometric reinforced concrete spaces blend with the setting's natural rock formations. Wright wanted the couple that commissioned the work to not just look out at the stream on their summer property but "live with the waterfall . . . as an integral part of [their] lives".[37] The American Institute of Architects has called Fallingwater "the best all-time work of American architecture".[38] | 39°54′22″N 79°28′5″W / 39.90611°N 79.46806°W | 11.212 ha (27.71 acres) [282.299 ha (697.58 acres)] |

|

1496rev-006 | Herbert and Katherine Jacobs House | Madison, Wisconsin | Built during the Great Depression, ideas for the Jacobs House (1937) grew out of an urban planning idea of Wright's that would provide a community of well-built, single-family affordable housing. Wright initially called this aesthetic Usonian, a word coined in the early 1900s for "American." Working within a budget of less than $5000, Wright combined his open design plan, functional spaces, and the use of wood, brick, dyed concrete, and large windows, to match a small landscaped neighborhood lot.[39][40] | 43°3′31″N 89°26′29″W / 43.05861°N 89.44139°W | 0.139 ha (0.34 acres) [1.286 ha (3.18 acres)] |

|

1496rev-007 | Taliesin West | Scottsdale, Arizona | In 1937 Wright began building his winter home, studio, and architectural fellowship center in the foothills of the Arizona's McDowell Mountains. The property was designed by Wright and his students, and built using timber, locally sourced stone, and a mixed sand concrete. Taliesin West was set within the landscape with overlapping indoor and outdoor rooms, a triangular garden of native plants, and triangular pool.[41] | 33°36′22.8″N 111°50′45.5″W / 33.606333°N 111.845972°W | 4.285 ha (10.59 acres) [198.087 ha (489.48 acres)] |

|

1496rev-008 | Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum | New York, New York | Wright's work for the Guggenheim Foundation in the 1940s and 1950s re-conceived the modern museum building as a place in conversation with the art within.[23] Placed across from Central Park, the spiral structure incorporates the sinuous forms of nature.[4][42] | 40°46′59″N 73°57′32″W / 40.782975°N 73.958992°W | 0.251 ha (0.62 acres) [2.164 ha (5.35 acres)] |

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Messman, Lauren (July 7, 2019). "Unesco Adds Frank Lloyd Wright's Architecture to World Heritage List". The New York Times. Retrieved December 14, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Goldsborough, Jamie Evelyn (July 8, 2019). "Eight Frank Lloyd Wright buildings are now UNESCO World Heritage Sites". The Architect’s Newspaper. Retrieved December 14, 2024.

- ^ "The 20th-century Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on July 9, 2019. Retrieved July 7, 2019.

- ^ a b "The Architecture of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum". Guggenheim.org. Archived from the original on July 12, 2019. Retrieved July 12, 2019.

- ^ Miller, Hugh C. (1973). "Chicago School of Architecture" (PDF). United States Department of the Interior. pp. 8–9. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 29, 2023. Retrieved July 12, 2019.

- ^ a b Allsopp, Phil (Fall 2008). "Preservation, Maintenance Key Funding Priorities for Capital Campaign". Frank Lloyd Wright Quarterly. 19 (4).

- ^ Goldstein, Lauren (June 29, 1990). "Taliesin preservation sought". The Capital Times. p. 24. Retrieved November 28, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "World Attention Fallingwater is Commanding a Greater View". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. January 26, 2008. pp. B.6. ProQuest 390486630.

- ^ For the list of nominated buildings, refer to: "New US World Heritage Tentative List". National Park Service. January 22, 2008. Archived from the original on October 26, 2012. Retrieved August 15, 2012; "Tentative List: Frank Lloyd Wright Buildings". UNESCO. Archived from the original on November 13, 2013. Retrieved October 17, 2013.

- ^ a b "Fallingwater to be proposed to U.N. World Heritage List". Latrobe Bulletin. July 14, 2011. pp. A5. Retrieved December 14, 2024.

- ^ Schumacher, Mary Louise (July 14, 2011). "Frank Lloyd Wright buildings to be nominated to World Heritage List". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Retrieved December 14, 2024.

- ^ Rein, Lisa (July 17, 2011). "Wright buildings, Louisiana's Poverty Point to be nominated for World Heritage List". Washington Post. ProQuest 877258974. Retrieved December 14, 2024.

- ^ a b Kamin, Blair (January 29, 2015). "Wright buildings to be nominated to list of significant world sites". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on January 29, 2023. Retrieved July 7, 2019.

- ^ "Frank Lloyd Wright Buildings Nominated for UNESCO Heritage List". Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation. February 17, 2015. Archived from the original on January 29, 2023. Retrieved June 29, 2019.

- ^ Edelson, Zachary (February 2, 2015). "Ten Frank Lloyd Wright Buildings Nominated for UNESCO Distinction". Metropolis. Archived from the original on November 28, 2024. Retrieved November 28, 2024; Winston, Anna (February 3, 2015). "Frank Lloyd Wright buildings nominated for UNESCO World Heritage List". Dezeen. Archived from the original on July 2, 2024. Retrieved November 28, 2024.

- ^ a b Geiling, Natasha (February 9, 2015). "Frank Lloyd Wright Buildings Nominated for Unesco World Heritage Status". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved December 14, 2024.

- ^ Kamin, Blair (July 20, 2016). "Frank Lloyd Wright sites don't make cut for UN World Heritage List". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved December 14, 2024.

- ^ Guarino, Ben (July 20, 2016). "UNESCO adds 21 new World Heritage sites, but Frank Lloyd Wright buildings don't make the cut". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 14, 2024.

- ^ a b "Eight Buildings Designed by Frank Lloyd Wright Nominated to the UNESCO World Heritage List". Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation. December 20, 2018. Archived from the original on June 25, 2019. Retrieved June 25, 2019.

- ^ Howarth, Dan (December 24, 2018). "Frank Lloyd Wright buildings re-nominated for World Heritage List". Dezeen. Retrieved December 14, 2024.

- ^ Stinson, Liz (December 20, 2018). "8 Frank Lloyd Wright buildings nominated to be World Heritage Sites". Curbed. Retrieved December 14, 2024.

- ^ "World Heritage Committee to meet in Baku (Azerbaijan) to examine inscription of new sites on World Heritage List". Mirage News. June 20, 2019.

- ^ a b Kamin, Blair (July 7, 2019). "Column: 8 Frank Lloyd Wright buildings, including Chicago's Robie House and Oak Park's Unity Temple, named to World Heritage List". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on January 29, 2020. Retrieved July 12, 2019.

- ^ Block, India (July 8, 2019). "8 Frank Lloyd Wright buildings added to UNESCO World Heritage List". Dezeen. Retrieved December 14, 2024.

- ^ Kamin, Blair (July 7, 2019). "Column: Why the addition of Frank Lloyd Wright buildings to World Heritage List is a big deal". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on July 12, 2019. Retrieved July 8, 2019.

- ^ Pfeiffer, Bruce Brooks (1995). The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. New York: Guggenheim Museum Publications. p. 5. ISBN 0-8109-6889-4. OCLC 35797856.

- ^ "NHLs Associated with Frank Lloyd Wright". National Park Service. March 29, 2007. Retrieved December 12, 2024.

- ^ Stiefel, Barry Louis (February 6, 2018). "Rethinking and revaluating UNESCO World Heritage Sites: Lessons experimented within the USA". Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development. 8 (1): 47–61. doi:10.1108/JCHMSD-02-2017-0006. ISSN 2044-1266.

- ^ "The 20th-Century Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright : Multiple locations". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on January 9, 2022. Retrieved July 7, 2019.

- ^ "Unity Temple". Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation. Archived from the original on November 14, 2019. Retrieved July 10, 2019.

- ^ Garcia, Evan (April 1, 2019). "Frank Lloyd Wright's Robie House Reopens After Massive Renovation". WTTW. Archived from the original on June 16, 2019. Retrieved July 10, 2019.

- ^ Desai, Sapna (April 22, 1019). "Robie House Reopens After Extensive Restoration". The Chicago Maroon. Archived from the original on July 10, 2019. Retrieved July 10, 2019.

- ^ Waldek, Stefanie (May 11, 2018). "7 Things You Didn't Know About Frank Lloyd Wright's Taliesin". Architectural Digest. Archived from the original on February 3, 2023. Retrieved July 10, 2019.

- ^ a b "Taliesin". Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation. Archived from the original on July 10, 2019. Retrieved July 10, 2019.

- ^ "Hollyhock House". Barnsdall Art Park Foundation. Archived from the original on November 20, 2019. Retrieved July 10, 2019.

- ^ "Hollyhock House". Los Angeles Conservancy. Archived from the original on July 11, 2019. Retrieved July 11, 2019.

- ^ Kamin, Blair (August 18, 2002). "Terrace firma ; Engineering feats shore up Fallingwater, restoring Frank Lloyd Wright's masterpiece". Chicago Tribune. p. 7.1. ProQuest 419704752.

- ^ "Fallingwater". Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation. Archived from the original on June 25, 2019. Retrieved July 11, 2019.

- ^ "First Jacobs House". WTTW Chicago. March 26, 2016. Archived from the original on January 29, 2023. Retrieved July 11, 2019.

- ^ Wright, Amy Beth (July 4, 2017). "Seven Hidden Gems from Frank Lloyd Wright's Usonian Period". Metropolis. Archived from the original on November 19, 2019. Retrieved July 11, 2019.

- ^ "Taliesin West". The Cultural Landscape Foundation. Archived from the original on July 11, 2019. Retrieved July 11, 2019.

- ^ "Organic Architecture". Guggenheim.org. September 8, 2010. Archived from the original on May 3, 2019. Retrieved July 12, 2019.