Robie House

| Robie House | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | 5757 South Woodlawn Avenue, Chicago, Illinois, United States |

| Coordinates | 41°47′23.4″N 87°35′45.3″W / 41.789833°N 87.595917°W |

| Area | 0.3 acres (0.12 ha) |

| Built | 1909 |

| Architect |

|

| Architectural style(s) | Prairie style |

| Governing body | The University of Chicago |

| Criteria | Cultural: (ii) |

| Designated | 2019 (43rd session) |

| Part of | The 20th-Century Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright |

| Reference no. | 1496-002 |

| Region | North America |

| Designated | October 15, 1966[1] |

| Reference no. | 66000316[1] |

| Designated | November 27, 1963[2] |

| Designated | February 14, 1979[3] |

| Part of | Hyde Park–Kenwood Historic District |

| Designated | September 15, 1971[4] |

The Robie House (also the Frederick C. Robie House) is a historic house museum on the campus of the University of Chicago in the Hyde Park neighborhood of Chicago, Illinois, United States. Designed by the architect Frank Lloyd Wright in the Prairie style, it was completed in 1910 for manufacturing executive Frederick Carlton Robie and his family. George Mann Niedecken oversaw the interior design, while associate architects Hermann von Holst and Marion Mahony also assisted with the design. Robie House is described as one of Wright's best Prairie style buildings[5] and was one of the last structures he designed at his studio in Oak Park, Illinois.

The house is a three-story, four-bedroom residence with an attached three-car garage. The house's open floor plan consists of two large, offset rectangles or "vessels". The facade and perimeter walls are made largely of Roman brick, with concrete trim, cut-stone decorations, and art glass windows. The massing includes several terraces, which are placed on different levels, in addition to roofs that are cantilevered outward. The house spans around 9,065 square feet (842.2 m2), split between communal spaces in the southern vessel and service rooms in the northern vessel. The first floor has a billiard room, playroom, and several utility rooms. The living room, dining room, kitchen, guest bedroom, and servants' quarters are on the second story, while three additional bedrooms occupy the third floor.

Fred Robie purchased the land in May 1908, and construction began the next year. The Robie, Taylor, and Wilber families lived there in succession until 1926, when the nearby Chicago Theological Seminary bought it. The seminary used the house as a dormitory, meeting space, and classrooms, and it attempted to demolish the house and redevelop the property in both 1941 and 1957. Following an outcry over the second demolition attempt, the developer William Zeckendorf acquired the house in 1958. He donated it in early 1963 to the University of Chicago, which renovated the house. The Adlai E. Stevenson Institute of International Affairs, and later the university's alumni association, subsequently occupied the Robie House. The National Trust for Historic Preservation leased the building in 1997, jointly operating it as a museum with the Frank Lloyd Wright Trust. The mechanical systems and exterior was renovated in the early 2000s, followed by parts of the interior in the late 2000s and the 2010s.

The Robie House was highly influential, having helped popularize design details such as picture windows, protruding roofs, and attached garages in residential architecture. The house has received extensive architectural commentary over the years, and it has been the subject of many media works, including books and museum exhibits. The Robie House is designated as a Chicago Landmark, a National Historic Landmark, and it forms part of a designated World Heritage Site.

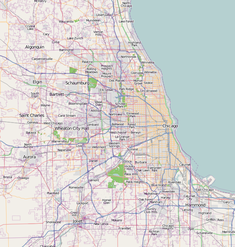

Site

[edit]The Robie House is located at 5757 South Woodlawn Avenue,[6][7] on the northeast corner of Woodlawn Avenue and 58th Street in the Hyde Park neighborhood of Chicago in Illinois, United States.[8] The lot measures 60 feet (18 m) wide and 180 feet (55 m) long, the larger dimension extending west–east parallel to 58th Street.[9][10][11][a] The house itself measures 60 by 154+3⁄4 feet (18.3 by 47.2 m) across.[12] Due to an existing covenant on the site, the Robie House and the neighboring residences are set back 35 feet (11 m) from Woodlawn Avenue.[13][14]

At the time of the Robie House's construction, the block immediately to the south was vacant, and the nearest building to the south was 1,400 feet (430 m) away, across the Midway Plaisance park. Due to the flat topography of Chicago's South Side, the site was also not particularly prominent.[15] The houses to the north, along Woodlawn Avenue, were set back from the street and were 2 feet (0.61 m) above the sidewalk.[13] These houses were largely made of brick.[16] Although the Robie House's architect, Frank Lloyd Wright, characterized the house as a "city dwelling", it was more akin to a suburban house in a streetcar suburb full of single-family homes.[17] To the west are the Rockefeller Chapel and the Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures.[18] To the south is the University of Chicago Booth School of Business building designed by Rafael Viñoly.[19]

History

[edit]The house was commissioned for Frederick Carlton Robie (1879–1962), a manufacturing executive who, in the 1900s, worked at his father's Excelsior Supply Company.[20][21] Robie married Lora Hieronymus in 1902, and they moved to Hyde Park, Chicago, in 1904, relocating again within the same neighborhood in 1907.[21] Concurrently, Robie wanted a residence that would incorporate the latest architectural innovations, rather than the old-fashioned details of conventional buildings.[22][23] He had sketched tentative plans for a house of his own, showing them to several builders, who told him, "You want one of those damn Wright houses."[14][24][25] At the end of 1906, Robie and Wright discussed the house for the first time.[24][25]

Development

[edit]Site acquisition and design

[edit]Robie decided to build his house at 5757 South Woodlawn Avenue, at the corner with 58th Street. This site was close to Lora's alma mater, the University of Chicago, where she was still socially active.[8][10] In April 1908, he agreed to obtain the site from the mining-machinery executive Herbert E. Goodman, on the condition that the site be used exclusively for residential purposes.[8] Robie bought the site on May 19.[8][26][b] As a condition of his purchase, he was required to spend at least $20,000 on a house there.[I][25]

Robie hired Wright to design the house, saying that "he was in my world" when it came to the design.[14] Robie recalled in 1958 that he had wanted a house illuminated by natural light, with uninterrupted living space, simple fixtures, and minimal bric-à-brac.[30][23] He also wanted several bedrooms, a nursery, and an enclosed yard for his children, and he wanted to be able to see outward without having passersby look in.[30][31][32] Robie eschewed older architectural styles such as the Cape Cod style, and he also did not want a monumental building or dark closets.[23] In addition, he wanted a fireproof house, particularly one made of steel and concrete.[32] The historian Joseph Connors wrote that Robie's recollections may have been tainted because he had lived in the house and read Wright's autobiography,[33] while the historian Donald Hoffmann wrote that Robie came to adopt many aspects of Wright's design philosophy as his own.[34] According to Hoffmann, the house was to be "radical and masculine", as Wright had designed the structure mainly around Robie's needs, not those of his wife.[35] Robie's original budget had been $60,000,[36][37][II] up to ten times the cost of a typical house at the time.[27][9]

Wright designed the Robie House in his studio in Oak Park, Illinois;[38] he was preoccupied with several other projects, so the design of Robie's residence was not a particularly urgent matter.[39] Wright first devised the plans for the Robie House mentally; unlike his contemporaries, Wright would focus on the building's symmetry and proportions rather than on its exact dimensions. One night, he sat down with a blank sheet of paper and sketched three diagrams for the house.[40] Wright paid so much attention to the house's architectural details, he drew up blueprints just for the carpets.[41] The original plans for the house may have been discarded or destroyed, but blueprints and renderings of the house remain extant.[42] Robie signed the working drawings for his house in late March 1909,[43][26] and construction began soon after.[44][26]

Construction

[edit]H. B. Barnard Co. of Chicago was hired as the contractor.[25][44] Robie recalled that the house did not need to use deep foundations and that the structural core—the chimney—was built rapidly.[25][45] According to Robie, H. B. Barnard personally inspected the house's brickwork every time laborers laid two or three courses of bricks.[45][28] Robie's son Frederick Jr. recalled playing with piles of sand (a material used in the mortar on the facade) and walking on the catwalks that contractors had set up.[37] During construction, some of the brickwork had to be disassembled after stonemasons accidentally built five brick piers, rather than two piers and three bollards, underneath the house's southern balcony.[46]

Interior work continued through late 1909,[47] and Wright left for Europe around that time.[48][49][50] He hired the interior designer George Mann Niedecken to furnish the Robie House.[48][51][d] Niedecken oversaw the interior decoration and the color scheme.[50] Also involved in the project were the architect Hermann V. von Holst, as well as one of Wright's draftswomen, Marion Mahony Griffin.[51] By early 1910, the house was nearly complete.[44] The furniture arrived in February, followed by curtains in March and carpets in April.[36]

Use as residence

[edit]The house was used as a residence for less than 20 years. During this time, it was used by three families: the Robies, Taylors, and Wilbers.[52][53] The Robie family—Frederick, Lora, and their two children, Frederick Jr. and Lorraine—moved into the home in May 1910, although interior decorations were not completed for several more months.[36][50] Robie said in 1958 that the house had cost about $59,000; the land cost $14,000, the design and construction cost $35,000, and furnishings cost $10,000.[27][28][29][III] This was far more than Wright's studio in Oak Park, which cost $4,700 in 1889; the Winslow House, which cost $20,000 in 1892; or the Willits House, which cost $20,000 in 1903.[29][IV]

Despite the house's high cost, the Robies owned the site for only two and a half years,[52][53] and they lived in the house for just over a year.[54] Frederick Robie's father died soon after the family had moved in.[55][54] Robie offered to pay his father's debts, which reportedly totaled roughly $1 million.[54][56][57][V] Lora Robie, who claimed that her husband had been unfaithful,[57] moved out of the house in April 1911 and subsequently filed for divorce, which was finalized the next year.[54] Frederick Robie moved to New York City, while Lora and their children moved to Springfield.[54] Frederick Jr. later recalled that the family had taken just one bed when they moved out.[58] When the elder Frederick declared bankruptcy in 1913, he reported having $25,672 in assets, nearly all of which consisted of a $25,000 mortgage loan that the Union Trust Company had placed on the house.[59] Despite Robie's personal issues, Wright would later call the residence "a good house for a good man".[57]

The Robies sold the house in December 1911[54][60] to David Lee Taylor, president of the advertising agency Taylor-Critchfield Company.[52] The final sale price was approximately 20% less than the construction cost.[51] David's son Phillips, who was 10 years old when his father bought the house, recalled that he frequently ran half-mile laps between the living and dining rooms, although his siblings did not join him.[61] David Taylor died in the house on October 22, 1912, less than a year after he bought the house.[62] Taylor's widow, Ellen Taylor, sold the house and most of its contents to Marshall Dodge Wilber, treasurer of the Wilber Mercantile Agency, that November.[61][63] Marshall reportedly paid $45,000 for the house;[63] he, his wife Isadora, and their two daughters lived nearby on Dorchester Avenue at the time.[61] According to Phillips, the only objects his mother took with them were a lamp, a chair, and a humidor.[61]

The Wilbers were the last family to occupy the house, moving in on December 3, 1912,[55][64] and living there for fourteen years.[51][60] The billiard room became a music room, and the living room became a parlor. The Wilbers employed a cook and a "second girl", who lived on site, and a handyman, who came to the house every day.[64] The Wilbers' residence sometimes hosted events, such as meetings of the Chicago Dramatic Society and the Quadranglers of the University of Chicago.[65] Marshall also constructed a machine shop near the garage, while Isadora hired three men to restore the facade c. 1913.[64] The roof and three windows were replaced in 1916, and the Wilbers decorated the house with several photographs of their 25-year-old daughter Marcia after she died that year.[66] The original coal-fired boiler was ineffective at warming the house during winter, so the Wilbers added an oil-fired furnace in 1919, replacing it in 1921. The Wilbers' surviving daughter, Jeannette, recalled that Wright often visited their house on short notice.[67] By 1926, Jeannette had moved out.[67] Marshall was in his sixties and wished to sell the house, as he was not in good health.[67][55]

Chicago Theological Seminary ownership

[edit]1920s to early 1950s

[edit]

In June 1926, the Wilbers sold their Woodlawn Avenue residence to the Chicago Theological Seminary,[55][68] whose campus was just to the south.[60] The seminary paid $90,000 for the house and the furnishings, which remained largely intact, except for a bedspread that Isadora took as a souvenir.[68] Originally, the residence was to be used as an administrative building until the seminary completed a new building.[69] The seminary used the house as a dormitory, meeting space, and classrooms,[53] though it wanted to redevelop the site in the long term.[60][70] Seminary officials placed some of the furniture in storage.[60] In addition, it sometimes gave tours of the Robie House.[52][60] The architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, the director of the Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT), was among those who toured the house.[71]

By 1941, the seminary was considering demolishing the house,[71][72] which was then being used as a women's dormitory.[72] A graduate student at IIT inadvertently learned of the demolition plans and informed his instructors, including Mies.[71] In response, writers such as Alexander Woollcott, Carl Sandburg, and Lewis Mumford, as well as architects such as Buckminster Fuller and Eliel Saarinen, protested the demolition.[71] One of Wright's apprentices, William F. Deknatel, led a committee to advocate for the house's preservation.[71][73] Ultimately, the plans were postponed due to World War II.[73] In 1952, the seminary applied for a zoning variance to convert the first story into a dormitory.[74] By that decade, the Robie House was being used for conferences,[75][76] and much of its original decorations had been destroyed.[70] At the time, the building was called the Conference House.[77]

Redevelopment plans

[edit]The University of Chicago's president Lawrence A. Kimpton was planning to redevelop the surrounding neighborhood.[78] As part of this project, Holabird & Root were hired to design a dormitory on the Robie House's site.[75][79] In response to a request from a local teacher, city alderman Leon Despres, who represented the neighborhood, introduced a resolution in the Chicago City Council to create a landmark commission.[79] In March 1957, the seminary announced that it would replace the Robie House with a dormitory,[75][78] which would have also involved demolishing the Goodman House and the Zeta Beta Tau fraternity house immediately to the north.[80] The seminary planned to begin demolishing the house that September,[81] saying it would have cost up to $100,000 to modernize the building.[82][83] The seminary's president Arthur Cushman McGiffert said that two institutions had declined an offer to take over the house and relocate it.[83]

Architects, students, and artists shortly expressed opposition to the proposed demolition, as did Despres and Chicago's mayor Richard J. Daley.[84] The University of Fine Arts of Hamburg,[85] the American Institute of Architects,[86] and fellows at Wright's Taliesin studio also opposed the demolition.[79] Wright himself returned to the Robie House on March 18 to protest its demolition,[82][87] saying, "It all goes to show the danger of entrusting anything spiritual to the clergy."[70][88] Wright claimed that the building was in relatively good condition, "considering the abuse it has suffered",[82][87] and that the kitchen was the only decrepit part of the house.[89][90] He also claimed that he could repair the house for $15,000.[76] McGiffert offered to move the house to Jackson Park or the Midway,[91] but Wright dismissed the idea as inappropriate.[92] Among other things, it would have cost hundreds of thousands of dollars to disassemble and rebuild the house elsewhere.[93] Wright offered to design a dormitory for the seminary if the Robie House remained in place, but the seminary declined his offer.[87][91] The Chicago government designated the house as a landmark in April 1957[92][94] and formed a committee of three men to preserve the house that July.[95]

Meanwhile, the University of Chicago chapter of Phi Delta Theta, Wright's old fraternity,[e] offered to swap ownership of the Robie House and its own fraternity house at 5737 South Woodlawn Avenue, three houses north.[80][81][83] The house's demolition was postponed while the fraternity negotiated with the seminary. By October, the seminary had tentatively agreed to give the house to the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation if the foundation raised $200,000.[81][VI] Phi Delta Theta and Zeta Beta Tau ultimately offered to donate their houses to the seminary.[81] Julian Levi, who led the South East Chicago Commission, asked his friend William Zeckendorf, whose real-estate development firm Webb and Knapp was developing structures in Hyde Park, if he wanted to temporarily occupy the house.[93] In December 1957, Zeckendorf offered to buy the Robie House for $125,000.[81][96][97][VII] To facilitate the house's sale, in February 1958, the seminary applied for permission to rezone the lots immediately to the north.[98] A City Council subcommittee recommended that August that the rezoning be approved.[99] Aline B. Saarinen, architecture writer for The New York Times, wrote that the houser's preservation "was an uphill fight the whole way".[100]

Zeckendorf and University of Chicago ownership

[edit]Acquisition and resale

[edit]

Zeckendorf formally acquired the house in August 1958,[101] paying $102,000, in exchange for allowing the seminary to approve any subsequent sales.[102] He planned to occupy it for four years.[96][97] Prior to taking over the house, he wanted to donate it to the National Trust for Historic Preservation,[93][97] and he suggested that the building could be converted to a library or museum.[96][103] Immediately after buying the house, Zeckendorf announced that he would instead donate it to the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation.[101] Although the agreement between Zeckendorf and the seminary specified that the National Trust would take over the house, the National Trust agreed to give the house to the Wright Foundation.[101] There were unofficial suggestions to turn the house into Chicago's official mayoral residence[104] or into an artists' studio.[105]

Zeckendorf's firm vacated the house in February 1962 after their Hyde Park developments were completed, and he wanted to donate the house to a "responsible organization" that could preserve it.[106] The University of Chicago agreed to take over the house in June 1962, in exchange for giving the seminary a nearby plot of land.[107] Two months later, preservationists formed a committee to raise $250,000 for the building's restoration.[108][109] William Hartmann of the architectural firm SOM said that structural repairs would cost $198,000, while the rest of the funds would be spend on furnishings.[108] There were suggestions for the house to be converted into a residence for visiting scholars, for the university's president, or classrooms for a department of the university.[110] Another proposal called for the National Park Service to take over the house and operate it as a monument.[111] Regardless of which option was selected, the university planned to allow visitors to tour the house.[107][112] The university formally took title to the Robie House on February 4, 1963,[113][114] and agreed to occupy the building and maintain it.[115]

University officials immediately began raising money for the restoration;[112][115][116] by then, the basement walls were leaking, the paint was peeling, and the wiring and mechanical systems were out of date.[113] More than 100 architects and academics from around the world were appointed to the restoration committee.[117] The university wanted to use the lower stories as a conference center, while the third floor bedrooms would be used by visiting scholars.[118] Students from various universities began touring the house in April 1963,[119] and the committee had collected about $31,000 by August.[120] Among the donors to the house's restoration were the Edgar J. Kaufmann Charitable Foundation[114] and Edward Bok's American Foundation.[121] The Robie House's fundraising committee spent $975 in late 1963 to repair damage caused by winter weather,[122] and it had raised about $40,000 by early 1964.[123][124] The fundraising committee continued to give tours of the house to raise money.[125][126] Ira J. Bach, who led the committee, said the house needed additional funds, even as it received donations from around the world.[123]

Usage

[edit]

In February 1965, the Wright Foundation determined that the house could be restored for $109,000, rather than the originally planned $250,000.[90] Taliesin Associated Architects, a firm composed of Wright's former acolytes, was hired to design the renovation.[127] Renovations began in mid-1965, after the University of Chicago had raised approximately $55,000.[102][128] The house also began opening to the public on Saturdays,[129] charging a $1 admission fee, proceeds from which would be used for the renovation.[130] The first phase included weatherproofing, plumbing, heating, and roof upgrades.[127][128][131] The house's original contractor, H. B. Barnard Co., was hired to rebuild the roof,[129] though the new roof was more vulnerable to water damage than the original.[56] The plaster surfaces were also repainted, and the window frames were replaced.[117] A second phase involved renovating the interiors, while the rest of the restoration was canceled due to a lack of funds.[131] The house was still vacant by 1966, and the University of Chicago needed another $200,000.[130] The same year, the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development announced a preservation program for historic buildings in Chicago, which would provide for the restoration of the Robie House.[132]

In July 1966, Adlai Stevenson III announced that the newly-formed Adlai E. Stevenson Institute of International Affairs, a think tank devoted to left-wing causes, would be headquartered at the Robie House.[133][134] The institute intended to convert part of the house into offices, and it would also host meetings and seminars there.[134] The house had no structural issues, so the institute hired SOM to refurbish the house and add some furnishings. At ground level, the entrance hall became a reception room; the billiard room became a library, and the playroom became a seminar hall.[135] The living room was converted to a lounge, the dining room retained its original function, and the second-floor guest rooms became a public relations office. The third-floor bedrooms also became offices.[136] The Stevenson Institute moved into the building in February 1967,[137] and the institute hosted its first party at the house in 1968.[138] Though the house was poorly suited as a workplace for the institute's 25 employees, the University of Chicago allowed the institute to stay there without paying rent.[139] Some of the Robie House's decorations were damaged in a burglary in 1970.[140][141]

The Stevenson Institute formally merged with the University of Chicago in 1975, and the university continued to use the house's meeting rooms.[142] The institute also allowed the public to make appointments to tour the house.[143] Subsequently, the university's office of development used the house, followed by the university's alumni association.[144] By the 1980s, the Robie House served as the alumni association's headquarters.[53][145] At the time, a reporter described the house as being in poor shape, with cracked walls, peeling paint, and damaged decorations due to patchwork repairs. Meanwhile, the university spent only $15,000 annually on maintenance, and it did not even try to obtain funding from external sources.[145] The house was filled with desks and cabinets.[53] The university continued to host guided tours of the Robie House for a fee,[53][146] though photography was not allowed at the time.[147] In addition, the interior tours covered only two[147][148] or three rooms.[149]

Frank Lloyd Wright Trust use

[edit]As early as 1992, the University of Chicago was negotiating to have the Frank Lloyd Wright Home and Studio Foundation (later the Frank Lloyd Wright Trust) take over the house's operation.[144][150] In February 1995, the University of Chicago announced that the building would be converted to a historic house museum.[148][150] The university would spend $2.5 million on renovations and turn over operations to the Frank Lloyd Wright Trust.[150][151] The National Trust for Historic Preservation agreed to lease the house in October 1996,[152] and the university moved out during early 1997.[144][153]

1990s and 2000s

[edit]

After taking over the house, the Wright Trust began hosting more frequent tours,[154][155] and it opened a bookstore in the garage in August 1997.[154] The Wright Trust planned to begin a 10-year-long renovation project in 2001,[156] which was to cost $7 million.[157][158] The bricks had cracked due to repeated freezing and thawing,[159] and there were stains, termite infestations, and deteriorated porches.[56][160] In addition, the roof was leaking, and the heating system was ineffective.[161] This prompted the trust to create a master plan for the renovation.[162] In 1999, workers removed asbestos from the site in preparation for the wider ranging renovation.[163][157] The house received a $1 million grant for its restoration through the Pritzker Foundation and the federal Save America's Treasures program.[9][164] The Illinois government also provided $2 million through the Illinois First program, which covered the remainder of the first phase of the renovation.[9]

A renovation of the Robie House commenced in 2002,[162] though the house continued to host tours in the meantime.[154][165] The conservation–restoration firm Gunny Harboe Architects oversaw the renovation.[166][167] As part of the first phase, workers documented the art glass, mechanical systems, and climate in the house; added wheelchair-accessible restrooms; and created architectural drawings.[162] Workers also fixed water damage, replaced the roof, and remedied the termite infestations.[168][160] In addition, new mechanical systems and utilities were installed, and the facade and terraces were stabilized.[168] The original brickwork manufacturer, Belden Brick, manufactured replacement bricks for the house.[56] This work was completed in 2003.[9][169] The third story remained closed to the public after the renovation,[158] since it did not comply with Chicago fire-safety regulations.[9][170]

The second phase, which involved renovating the interior, was delayed due to a lack of funds.[9][171] Visitation, and by extension revenue, had declined after the September 11 attacks;[9] at the time, the trust needed another $4 million for the interior.[160][171] The trust sold engraved bricks to finance the renovations of the Robie House and Wright's Oak Park studio.[172] Work on the pantry and dining room began in 2006 or 2007,[169] with an estimated cost of $3 million.[166][173] During its renovation, the house continued to host tours and events.[174] In 2009, the trust began allowing visitors to tour the third floor and servants' rooms, and it began allowing visitors to interact with artifacts from the house.[175] By then, the house hosted 30,000 visitors annually.[56] The trust wanted to reproduce or build replicas of the original decorations and fixtures.[169]

2010s to present

[edit]The Frank Lloyd Wright Trust continued to raise funding for the house's renovation.[176] In 2014, the house received a grant through the Getty Foundation's Keeping It Modern initiative;[177] the $50,000 grant was used to develop a preservation plan.[178][179] By then, the trust had already raised $2 million of a projected $6 million renovation budget.[178] The same year, the house became part of Museum Campus South, a group of museums in Hyde Park.[180] An interior restoration began in late 2017,[11] covering the first and second stories.[167] The interior restoration focused on the interior elements, such as woodwork, glass, and furniture.[181] Workers restored original design elements such as millwork and sconces,[166] and the project involved repainting the house to its original colors and repairing the original front door.[167][173][182] The Frank Lloyd Wright Trust borrowed some of the house's original furniture from the Smart Museum of Art.[173]

The restoration was completed in March 2019,[173][182] having cost $3.5 million.[11] In total, the renovation project had cost over $11 million.[183][181] Tours of the house were suspended in March 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic in Illinois.[184] The house reopened that June,[184][185] though tour groups were initially restricted to eight people.[185]

Architecture

[edit]

The Robie House (also known as the Frederick C. Robie House[186]) is designed in the Prairie style.[187][188] Wright wanted the architecture, art, and furnishings to have a consistent design;[174] and he aspired for the house to be a Gesamtkunstwerk, an ideal work of art.[27][50] Though many components of the Robie House were symmetrical or nearly so,[189] the house as a whole is asymmetrical.[190] The author Joseph Connors writes that Wright's use of symmetrical details had been inspired by the teachings of Friedrich Fröbel and the École des Beaux-Arts.[189] The design shares elements with Wright's F. F. Tomek House in Riverside, Illinois,[13][191] and his Larkin Administration Building in Buffalo, New York.[192] Connors cites the Yahara Boat Club in Madison, Wisconsin, and the River Forest Tennis Club in River Forest, Illinois, as additional forerunners to the Robie House.[193]

In designing the Robie House, Wright largely avoided the cruciform and pinwheel plans that he had used in previous houses.[43] The house still uses a variation of a pinwheel plan, albeit one in which the west–east axis is more heavily emphasized than the north–south axis.[194][195] The house's floor plan consists of two large rectangles, or "vessels", offset from one another.[39][196] Each vessel is about one-half the site's length.[39] The southern, primary vessel extends west and contains communal spaces,[39][197] which terminate in prow-shaped bays to the west and east.[194][198] The northern, secondary vessel extends east and contains service rooms, such as the kitchen and entrance hall.[43][197]

Exterior

[edit]Unlike similar houses, which had roofs supported by load-bearing walls, the Robie House's roofs are cantilevered outward from the house's core. The exterior walls are treated as curtain walls or non-structural screens.[199] In addition, Wright wanted people to view the house primarily from its southwest corner, where 58th Street and Woodlawn Avenue intersect.[200] In contrast to his contemporaries, who prioritized exterior design over interior design, Wright believed that the facade's design should be subordinate to the house's interior function.[126]

Because the site was flat and significantly longer on one side, Wright designed the house as a long, low building,[13][17] similarly to other Prairie style buildings.[188] As such, even though the house is three stories tall, the massing gives the impression of a single-story house with a small attic.[17] The strong horizontal emphasis of the design was atypical of contemporary homes, which generally emphasized their vertical details.[7][201] According to Wright, the low-to-the-ground design was intended to give the house a "more intimate relation with outdoor environment and far-reaching vistas".[202] As it was not possible for Wright to add a garden, the house is instead decorated with urns and planters.[6][203] The primary rooms on the second story are raised;[12][13] this provided privacy, as it allowed views outward while preventing passersby from looking in.[22][174][196] The house is set back from Woodlawn Avenue, but the main roof and one perimeter wall extend past the western elevation of the facade, reducing the visual effect of the setback.[204][203]

Facade

[edit]

The house sits on a water table made of concrete,[6][205] while the facade is made largely of brick.[12] The house also uses concrete for balconies; cut stone for window sills and copings; and a wood frame for the third story.[47] According to Frederick Robie Jr., Wright ordered custom-made bricks for the house, which measure 1+5⁄8 by 11+5⁄8 inches (41 by 295 mm) across.[37] The low, narrow bricks in the facade are laid horizontally.[6][205][197] The bricks are colored violet, red, and orange with scattered dark spots.[9][205] Wright emphasized the horizontal axis further by deepening the horizontal joints between each row of bricks,[110][113] while filling in the vertical joints.[206] The horizontal joints were infilled with mortar in the mid-20th century.[110][113] The water table and cut-stone sills and copings were also oriented horizontally, further emphasizing the fact that the house was low to the ground.[205] The northern facade is a plain brick wall.[207] An L-shaped chimney rises from the center of the house; it is topped by a brick closet leading to a rooftop balcony.[208]

Wright incorporated horizontal bands of windows into the facade.[209] These windows are made of art glass to blur the distinction between indoor and outdoor spaces[210] and to illuminate the rooms.[143] In contrast to double-hung windows, which consist of sliding window panes stacked above each other, Wright used casement windows, which are side-by-side and can swing outward.[211] There are 175 art glass panels throughout the house,[56][170][212][f] arranged in 29 patterns.[201] These panels have intricate, vertically oriented geometric motifs.[211]

The main entrance leads to the first floor[203][213] and is recessed significantly from the western facade on Woodlawn Avenue.[214][215][216] The entrance courtyard has a floor made of red tiles.[214][216] A staircase leads up to a porch hanging off the western side of the second floor.[203][214] There are three additional entrances to the house from the eastern driveway, which lead to the first-floor playroom, the first-floor laundry and furnace room, and the second-floor kitchen.[217] An ornamental gate was originally installed outside the driveway.[217][218] A brick perimeter wall runs along the northern and eastern boundaries of the site.[207][219] The wall originally was about one story high;[189] the top of the wall was shortened in the 1960s[220] to provide bricks for the construction of a storage room near the garage.[12]

The house's attached garage can fit three cars.[113][213] The attached garage was a novelty when the house was built;[221][111] at the time, cars were considered especially vulnerable to catching fire, so houses generally had detached garages.[222] To visually separate the garage and the rest of the house, Wright added a gap to the roof, and he added posts and lintels beneath the rooftop gap.[223] The garage functions as a bookstore for the museum.[154][212]

Terraces and roofs

[edit]The massing includes several terraces on different levels.[224] The largest such terrace is a balcony on the south side of the second floor,[13][206][215] which has a brick parapet.[22] It measures 40 feet (12 m) long[50] and is accessed by a row of 12 French doors.[125][225][226] The southern balcony is supported by several metal beams, which are concealed beneath a stone coping and are flanked by brick columns.[206] During construction, Wright added a pit at each end of the balcony, and the French doors next to these pits were converted to windows.[226] Under the balcony are two full-height brick piers, alternating with three half-height brick bollards.[46] There is another balcony to the northwest, a porch to the west, and several smaller porches hanging off the building.[13] The western porch measures 9+2⁄3 feet (2.9 m) wide and is cantilevered off the western facade.[50]

The house is topped by several hip roofs, which have shallow pitches[12] and are made of red Ludowici tile.[227] The roofs have projecting eaves, emphasizing the horizontal orientation of the facade,[6][14] and there are upturned bronze gutters.[228] Above the second floor, a shallow eave allows light to be reflected off the second-story terrace into the living and dining rooms. There is a deeper eave above the third-story bedrooms.[216]

Interior

[edit]

The house has around 9,065 square feet (842.2 m2),[50] with four bedrooms, six bathrooms, eleven closets, and a servants' quarters.[29] In contrast to contemporary residences, the Robie House has several open plan spaces,[7] and it lacks side rooms such as a reading room and a women's lounge,[190] Wright used low ceilings throughout the house,[53][90] juxtaposing them with high ceilings for esthetic effect.[229] The superstructure is made of horizontal steel beams and brick piers.[6][230] Steel is used extensively, including under the terraces and in the living-room ceiling,[220] the latter of which uses bolted-steel beams 15 inches (380 mm) thick.[37][50] The house had a central lighting system,[231][232] which was operated from three control panels.[111] There were also a central vacuum system,[61][190] burglar and fire alarms,[232] a valve to water all the planters,[61] and a heating and air-cooling system.[231][233] Radiators for the heating and cooling system are concealed in cabinets,[234] and there are also four fireplaces.[201]

Originally, the rooms were decorated in a cream, brown, ocher, and salmon color scheme.[50] Rougher-textured paint was used in bedrooms, while smoother paint was used in the communal areas.[11] The house was originally illuminated by 30 sconces designed by Wright, of which only two remained in the 1960s.[235] Wright designed two types of sconces: oak and brass fixtures for the bedrooms and other private spaces, and frosted-glass fixtures for communal spaces.[56] The house includes eight Japanese–inspired oak screens, which served as partitions; each screen consists of square bars measuring 1+5⁄8 inches (41 mm) thick.[236] To provide privacy, some of the windows have roller shades.[211] Lora Robie's closet includes built-in hooks, since clothes hangers had not been invented when the Robie House was built.[237]

First story

[edit]In contrast to the light-filled upper stories, the first story is a dark space with low ceilings.[238][239] From the main entrance on Woodlawn Avenue, visitors had to follow a circuitous path to access the rest of the house.[203] The entrance foyer is on the first (ground) floor of the northern vessel[240] and has a plaque on its east wall.[236] The billiard room and playroom are to the south of the foyer; a coat closet and a stair to the second-floor kitchen are to the east; and a bathroom is to the north.[240] The coat-closet doorway and the foyer's southern doorway both have movable oak screens. There is also a window alcove on the north wall, next to a radiator with three windows.[241]

The billiard room was originally at the west end of the southern vessel, while the playroom occupied the east end.[110][242] The windowless western wall of the billiard room, which exists mostly to support the living room above it, could be used as storage space or as a wine cellar.[211] The billiard room's northern wall has clerestory windows with lozenge motifs.[243] On the southern wall is a small garden and a concrete terrace.[17][243] The billiard room is separated from the playroom by a stairway leading to the second floor.[213][238] Within the playroom, there is a cantilevered bench within an inglenook,[218] as well as a prow-shaped niche to the east.[90][218] The billiard room and playroom both have individual fireplaces.[201] Subsequent owners used wood-and-plasterboard partitions to divide the playroom and billiard room into six rooms.[110]

The Robie House has a partial cellar with a boiler plant.[12][118][230] The house does not have a full cellar because the site was originally swampland[12] and because Wright did not want to excavate the "damp sticky clay of the prairie".[240] The boiler plant, consisting of a coal room and furnace room, is only four steps below ground.[240] It is located at the west end of the house's northern vessel, along with the coat room, laundry, and workshop. At the east end of the northern vessel's first story is the garage.[242] There were maintenance pits in the garage,[9][174] but these were filled in when the garage was converted into offices in the mid-20th century.[240] The garage and the other service rooms could be accessed only from the outside.[240]

Second story

[edit]

In designing the second floor, Wright sought to eliminate "boxes beside or inside other boxes" by blurring the boundaries between the rooms.[110] The rooms were still distinguished from each other by the use of different cabinetry and carpet designs.[244] The stairway from the center of the first floor leads to an intermediate hall on the second floor, between the northern and southern vessels.[215][239][244] The stair hall is separated from the southern vessel by a 5-foot-tall (1.5 m) screen made of wooden slats.[245] Movable portières, or curtains, hang above the doorways in the stair hall.[238][244] In addition, the stair hall has a bookcase on its northern wall, and a doorway leads northwest to the guest bedroom's balcony.[244]

The living and dining rooms in the southern vessel have similar design features and are separated only by a fireplace.[228][242] Their ceilings vary in height, dividing both rooms into three bays from north to south.[29][246] The outer bays have 7.5-foot (2.3 m) ceilings, while the central bay has 9-foot (2.7 m) ceilings.[246] Wooden boards, which are designed to resemble ceiling beams, span the ceiling's width.[231][246] The spaces are illuminated both by recessed lights above the outer bays (which are hidden behind grilles), as well as spherical lamps.[29][246][247] There is also a chimney flue and ventilation openings near the ceiling, in addition to two steel beams that support the roof.[246] The house's south balcony extends from the living and dining rooms,[228][248] and both rooms have decorative wooden screens as well.[238][244]

The living room occupies the western part of the southern vessel.[242] The prow on the living room's west wall serves as a niche[89][246] and has windows and doors with multicolored glass.[249] The north wall of the living room has five casement windows, while the western section of the south wall has a narrow sidelight and casement window. The carpet is decorated with a rose rectangle and a dozen green squares.[247] The fireplace between the living and dining rooms has narrow brick piers[250] and a fieldstone mantel.[111] The fireplace serves a mostly ceremonial function, since the house is heated by concealed radiators.[246][250] The dining room is east of the living room;[242] its east wall has a breakfast nook within a bay window.[238] The north wall of the dining room has a wooden sideboard, complementing the French doors on the opposite wall.[245][251]

The northern vessel includes servants' quarters, a kitchen, and a guest room.[252][194] The guest bedroom, at the western end,[242] has a carpet with rotated squares and vessel motifs.[253] The guest room's bathroom has frosted-glass windows,[252] and a balcony next to the guest bedroom overhangs the entrance court.[238][239] A stairway separates the guest room from the kitchen, which is located at the center of the northern vessel.[242] The kitchen has a plain design with casement windows and some wood and glass decorations.[254] At the east end of the northern vessel, there are three servants' rooms,[126][29] above the garage.[213] These consist of two bedrooms for maids, in addition to a servants' dining room.[29][242] The servant bedrooms have flower boxes, intricate casement windows, and sloped ceilings.[254]

Third story

[edit]

A stairwell leads from the second story to the third story, which Wright described as a "belvedere".[194][254] The third floor is T-shaped in plan, with the stem of the T being above the northern vessel;[189][255] the floor plan vaguely resembles a Greek cross with asymmetrical arms.[256] The third story abuts the chimney to its west and visually connects the vessels below it.[256] It has three bedrooms,[39] each of which overlooks a balcony with planters and urns.[29] The master bedroom occupies the southern end of the T.[256] The master bedroom has a walk-in closet, a master bathroom, a dressing room with built-in drawers, and a fireplace.[29][257] Another bedroom at the northwest corner overlooks Woodlawn Avenue and has a closet and glass decorations. The smallest bedroom in the house is at the northeast corner, whose windows mostly face eastward. In all three bedrooms, there are small casement windows for flower boxes.[257]

Furniture

[edit]Wright designed many pieces of the house's original furniture.[197] George Niedecken built much of the furniture,[29][258] which was made of oak.[12] In the foyer, there were objects such as oak furniture and patterned carpets.[240] The foyer's oak furniture, which included a cantilevered table, a geometrically patterned table scarf, and chairs, was intended to complement the design.[259] The living room's original furniture included a sofa with extended armrests.[163] The living room also included a bench with side tables; a smoker's cabinet; a small study with a desk and lamp; and movable chairs.[260][261] The dining chairs had high seatbacks to give the dining table a more intimate feel,[251][260] thereby creating a "room within a room".[9] The rectangular dining table was expandable and had table scarves.[262] There were lampposts at each of the dining table's corners,[245][260] which were intended to draw diners' focus toward the center of the table, discouraging side conversations.[147] The house also had an imported Austrian carpet.[12][263] For the guestroom, Wright designed a dresser, a double bed, and side chairs.[253] Wright did not design the third-story furniture, which included wardrobes and built-in drawers.[257]

When the house was converted into the Stevenson Institute's headquarters in the 1960s, some contemporary furniture designed by SOM was added to the house, including upholstered chairs. The house's original sofa was reproduced at that time.[136] By then, the house was decorated in a plum, dark red, brown, and saffron gold color palette. Some pieces of furniture were upholstered in silk, wool, or mohair, while other furnishings (primarily seating) were covered with natural leather.[264]

Some of Wright's original furniture is in the collection of the University of Chicago's Smart Museum of Art.[70][9] The Smart Museum also owns disassembled pieces of furniture from the Robie House, pieces from other Wright houses, and pieces not designed by Wright.[70] In 2019, the Smart Museum lent the dining chairs and table to the Frank Lloyd Wright Trust.[173] The original sofa, also in the Smart Museum's collection, has been on loan to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York since 1982.[265] When the house was being considered for demolition, some of the art glass windows were moved to a police station at the University of Chicago.[9] Replicas of the Robie House's dining room chairs,[266] the lamps,[267] the sconces,[268] and the cantilevered living-room couch have also been sold.[269] A lamp from the house was auctioned off for $704,000 in 1988, making it the most expensive Wright–designed furnishing ever sold at the time.[270]

Management

[edit]

The University of Chicago owns the house, leasing it to the National Trust for Historic Preservation,[153][158] which jointly operates the museum with the Frank Lloyd Wright Trust.[156] The Wright Trust hosts guided tours of the house, which are hosted five days a week[170] and last 45 to 60 minutes each.[271] There are also audio tours of the house.[272] The third floor is excluded from most of the house's tours but is part of the "Private Spaces" tour.[170][175] The Robie House is part of the annual "Wright Plus" walking tour,[273] which includes visits to several buildings designed by Wright.[274] Since 2018, the Robie House has been part of the Frank Lloyd Wright Trail, a collection of 13 buildings designed by Wright in Illinois.[275]

The trust typically hosts training courses for volunteer tour guides twice annually.[276] Over the years, the trust has trained several grade-school students as tour guides.[277] In addition, the trust rents out the house for events.[278]

Impact

[edit]Reception

[edit]When the Robie House was built, local residents disliked how the building stood out from its surroundings.[160][161] The house was viewed more positively in the architecture community,[279] though its historic significance was not widely recognized until the 1930s.[280] After its demolition was proposed in 1957, The Christian Science Monitor described the house as "one of the most important works of one of the world's most influential architects", calling the proposed demolition a "needless tragedy".[281] Another commentator called the Robie House "for many Americans the finest work of art turned out by any of our architects in our history as a nation."[282] The Swiss architect Werner M. Moser said that Europeans regarded the Robie House "as a monument of historic value".[116] The Chicago Tribune said in 1965 that a visit to the house's living room was comparable to seeing a Giotto painting or hearing a Ludwig van Beethoven symphony for the first time.[89]

A critic for the Chicago Tribune said in 1984 that "the strength and vitality that turned so many heads in 1909 still shine brightly."[53] The same year, Donald Hoffman said that the house "embraced so many opposite tendencies"; for instance, the house's attic contrasted with its low-lying form, and its closed-off exteriors stood in contrast to the openness of the interiors.[219] Robert Campbell of The Boston Globe called the Robie House "probably the greatest the master [Wright] ever did", along with Fallingwater in Greater Pittsburgh.[145] The Condé Nast Traveler wrote that "the essential integrity of the design, inside and out, is intact and engrossing".[271] The writer Neil Levine said that the Robie House felt "buoyant and spacious" despite its low-lying massing,[17] and a writer for The Ottawa Citizen said the house was representative of the "energy and optimism" that characterized the early 20th century.[190]

The house has been the subject of various comparisons. A writer for The Wall Street Journal described the Robie House as "a sheet cake that wants to be a ziggurat".[174] Other sources called the building a "quintessential Prairie School house"[263] and one of his best Prairie style structures.[5][176] Writers have also likened the building's low massing to a ship,[159][141][283] and it was described as an example of "Dampfer architecture", in reference to the German word for "steamship".[27][232] Another source described the house as the "culmination" of Wright's early work.[158]

Architectural influence

[edit]

The Robie House was one of the first residences in the U.S. to be made of cement blocks and poured concrete.[124] A writer for The Sydney Morning Herald said that some of the house's design features had since become commonplace, including cantilevered slabs, concrete floors, and corner windows.[284] The house's continuous windows and protruding roof were also popularized nationwide.[285] Newspapers have cited the house as having introduced other architectural details, such as spare bathrooms, self-watering planters, attached garages, picture windows, and split-level spaces.[111][147] Some of the house's architectural features had been used in Wright's previous designs, such as Warren McArthur's house[286] and Wright's Oak Park studio.[287] The Robie House was one of the most prominent buildings that Wright designed in his Oak Park studio,[141][288] as well as one of the last structures he designed there.[49] Wright himself considered the house to be a "cornerstone of modern architecture".[289]

The Commission on Chicago Landmarks said: "The bold interplay of horizontal planes about the chimney mass, and the structurally expressive piers and windows, established a new form of domestic design."[290] A 1957 article in House & Home magazine said that "The house introduced so many concepts in planning and construction that its full influence cannot be measured accurately for many years to come",[291][292] calling it the most consequential house to be built in the U.S. in a century.[292] Similarly, The Christian Science Monitor said in 1962 that the Robie House was Wright's first residence to "have an effective influence on modern residential architecture",[293] and Walter Gropius called the house "a milestone in independent architecture".[213]

In contrast to the Robie House, Wright's later designs (with exceptions such as Fallingwater) were not designed with a diagonal vantage point in mind. Nonetheless, some architects such as Ludwig Mies van der Rohe did design buildings that were intended to be viewed from an angle.[294] The Robie House's other architectural features inspired architects in Europe, starting with the Dutch architect J. J. P. Oud, who in 1918 was the first to publish an article about the house.[294][279] These features influenced the design of European structures such as Mies's Barcelona Pavilion and the Rietveld Schröder House.[279] In turn, American architects began using these design features in the 1930s.[60] Specific structures influenced by the Robie House include a residence in Franklin Park, Pennsylvania;[295] the Domino's Pizza headquarters in Ann Arbor, Michigan;[296] and a residence on Navajo Avenue in Edgebrook, Chicago.[183] Decorations from the house, such as the sconces, have also been replicated.[297]

The Robie House was listed as "one of the seven most notable residences ever built in America" in a 1956 Architectural Record article.[201][298] A 1976 poll of American-architecture experts ranked the Robie House among the top structures in the U.S.,[299] while a 1982 poll of Architecture: the AIA journal readers ranked the Robie House as the country's third-best building.[300] In 1991, the American Institute of Architects (AIA) named the house among the Top All-Time Work of American Architects.[197][301] In celebration of the 2018 Illinois Bicentennial, the Robie House was selected as one of the Illinois 200 Great Places by AIA's Illinois chapter.[302]

Landmark designations

[edit]Chicago's Commission on Architectural Landmarks designated the Robie House as a landmark in 1957, in an attempt to stave off the building's demolition.[115][92][94] The house was also the first 20th-century building that the National Trust for Historic Preservation tried to preserve.[87] The AIA's Chicago chapter gave the building's owners a plaque in 1960, recognizing the building as a landmark.[303] After the Commission on Chicago Landmarks replaced the Commission on Architectural Landmarks in 1968,[304] the Robie House was again nominated for city-landmark designation in early 1971.[305] At the landmark commission's recommendation,[306] a Chicago City Council committee approved the designation that August.[307] The Commission on Chicago Landmarks' designation applied only to the exterior[308] and prevented unauthorized alterations.[304]

When the house was being considered for demolition in 1957, the National Park Service initially refused to consider preserving the house, as it was not yet 50 years old.[280] The Robie House was ultimately designated as Chicago's first National Historic Landmark in July 1963,[309] and a plaque affirming this designation was dedicated in April 1964.[124][310] The house was also added to the National Register of Historic Places on October 15, 1966,[1] the day the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 went into effect.[311] The Robie House is a contributing property to the Hyde Park–Kenwood Historic District, designated in 1979,[3] and the house was further designated as an Illinois Historic Landmark in 1980.[2]

The United States Department of the Interior nominated the Robie House and nine other Wright–designed buildings to the World Heritage List in 2015;[312][313] the buildings had previously been nominated in 2008.[314] UNESCO added eight properties, including the Robie House, to the World Heritage List in July 2019 under the title "The 20th-Century Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright".[315]

Media and exhibits

[edit]The Robie House was detailed in Ernst Wasmuth's 1910 Wasmuth Portfolio.[27][g] The Historic American Buildings Survey cataloged the building's architectural details and floor plans in the 1960s,[316] and Donald Hoffmann wrote a book about the house in 1984.[317] In addition, presentations from a 1984 symposium at the house were published in the book The Nature of Frank Lloyd Wright.[318] An animated tour of the house was released on CD-ROM in 1995,[149][319] and the house was depicted in a stamp issued by the United States Postal Service in 1998.[320] The house has been the subject of several documentary films, including a 1975 BBC documentary,[321] a 2004 episode of HGTV's Restore America: A Salute to Preservation series,[322] and the 2013 PBS documentary and companion book 10 Buildings that Changed America.[323]

Several exhibits have featured the Robie House. For example, models of the house were displayed at the Cincinnati Art Museum in 1933[324] and at the Exhibition of American Art in Paris during 1938.[325] The house was also featured in several exhibits at New York City's Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in 1941, 1961, and 1994,[326] and a model of the house was displayed at MoMA in 1964.[327] Furniture from the house was displayed at the University of Chicago's Smart Museum of Art in 1979.[328] and at the National Gallery of Art,[329] while chairs from the house was displayed at New York's Cooper Hewitt Museum in 1983[330] and at the Boston Design Center in 1992.[331] The Chicago Athenaeum organized an exhibit about the Robie House and Wright's other Chicago designs in 1992.[332]

The house has been depicted in other creative works as well. For instance, the graphic designer Steven Brower cut a pizza box into the shape of the Robie House.[333] Edmund V. Gillon Jr. released a model of the house in 1998,[334] and a rendering of the house was also included in a 2002 pop-up book about Wright's work.[335] Lego started selling a model of the Robie House in 2011.[336] In addition, Blue Balliett's mystery novel The Wright 3 was set in the house.[337]

See also

[edit]- List of Frank Lloyd Wright works

- List of Chicago Landmarks

- List of National Historic Landmarks in Illinois

- List of World Heritage Sites in the United States

- National Register of Historic Places listings in South Side Chicago

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]Explanatory notes

- ^ National Park Service 1966, p. 2, gives different dimensions of 60 by 200 feet (18 by 61 m).

- ^ a b In 1958, Robie claimed to have bought the land for $14,000 (equivalent to $335,000 in 2023).[27][28][29] However, other sources give a figure of $13,500 (equivalent to $323,000 in 2023).[8][26]

- ^ a b c d e f g Johnston, Louis; Williamson, Samuel H. (2023). "What Was the U.S. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved November 30, 2023. United States Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the MeasuringWorth series.

- ^ For an in-depth description of the working relationship between Wright and Niedecken in connection with the Robie House, see Robertson, Cheryl; Wright, Frank Lloyd; Niedecken, George M.; Milwaukee Art Museum (1999). Frank Lloyd Wright and George Mann Niedecken : Prairie School collaborators. Milwaukee, Lexington, Mass.: Milwaukee Art Museum ; Museum of Our National Heritage. ISBN 978-1-889541-01-3. OCLC 41038278.

- ^ When he was a student at the University of Wisconsin, Wright had joined that university's chapter of Phi Delta Theta.[80]

- ^ One pane was later removed, so sources have also cited the house as having 174 panes of glass.[212] Hoffmann 1984, p. 53, gives a different figure of 265 panes.[211]

- ^ An online copy of the Wasmuth Portfolio, including Plate XXXVII of Volume 2 containing a rendering of the Robie House and third floor plans, as well as an overlay of the first and second floor plans, is available through the J. Willard Marriott Library at the University of Utah.

Inflation figures

- ^ Equivalent to $476,000 in 2023[c]

- ^ Equivalent to $1,427,000 in 2023[c]

- ^ The total cost is equivalent to $1,403,000 in 2023. This is broken down into $333,000 for the land,[b] $833,000 for the design and construction, and $238,000 for the furnishings.[c]

- ^ This is equivalent to the following in 2023:[c]

- Wright's studio: $144,000

- Winslow House: $607,000

- Willits House: $545,000

- ^ Equivalent to $23,788,000 in 2023[c]

- ^ Equivalent to $1,659,000 in 2023[c]

- ^ Equivalent to $1,037,000 in 2023[c]

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ a b "Frederick C. Robie House". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Archived from the original on July 31, 2012. Retrieved June 11, 2008.

- ^ a b "National Register of Historic Places Inventory – Nomination Form" (PDF). Illinois Historic Preservations Society. February 14, 1979. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 28, 2009. Retrieved November 1, 2011.

- ^ "Chicago Landmarks – Robie House" (PDF). 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 18, 2016. Retrieved August 26, 2016.

- ^ a b Huxtable, Ada Louise (May 15, 1972). "Metropolitan to Set Up Wright interior". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 23, 2025; Ure-Smith, Jane (June 27, 2009). "Architectour of Chicago". Financial Times. Retrieved January 25, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f Sanderson, Arlene, ed. (2001). A Guide to Frank Lloyd Wright Public Places: Wright Sites. Princeton Architectural Press. pp. 41–42. ISBN 978-1-56898-275-5. Retrieved January 20, 2025.

- ^ a b c Davis 2013, p. 209.

- ^ a b c d e Hoffmann 1984, p. 6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Donovan Daily Herald, Deborah (February 7, 2003). "Renovation for Robie Restoration continues on Wright's prairie- style masterpiece". p. 1. ProQuest 312702899.

- ^ a b Lucas 2006, p. 9.

- ^ a b c d Clark, Brian E. (July 12, 2019). "Frank Lloyd Wright-designed Robie House in Chicago's Hyde Park is now a UNESCO treasure". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Retrieved January 27, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i National Park Service 1966, p. 2.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hoffmann 1984, p. 17.

- ^ a b c d McCarter 1997, p. 93.

- ^ Hoffmann 1984, p. 15.

- ^ Hoffmann 1984, p. 13.

- ^ a b c d e Levine 1997, p. 53.

- ^ "Zoning Website". City of Chicago. Retrieved January 26, 2025.

- ^ Kamin, Blair (February 22, 2000). "U. Of C. Looks Outside Again for Architect". Chicago Tribune. p. 2C.3. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 419011952.

- ^ Connors 1984, p. 5.

- ^ a b Hoffmann 1984, p. 5.

- ^ a b c Gill 1987, p. 193.

- ^ a b c Architectural Forum 1958, p. 126.

- ^ a b Connors 1984, p. 7.

- ^ a b c d e Architectural Forum 1958, p. 127.

- ^ a b c d Smith 2008, p. 6.

- ^ a b c d e f Hoffmann 1984, p. 14.

- ^ a b c Architectural Forum 1958, p. 206.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Connors 1984, p. 39.

- ^ a b Connors 1984, p. 8; Hoffmann 1984, p. 8.

- ^ Architectural Forum 1958, pp. 126–127.

- ^ a b Lucas 2006, p. 8.

- ^ Connors 1984, p. 9.

- ^ Hoffmann 1984, p. 9.

- ^ Hoffmann 1984, pp. 12–13.

- ^ a b c Hoffmann 1984, p. 34.

- ^ a b c d Architectural Forum 1958, p. 210.

- ^ Daniels, Mary (February 7, 1982). "Resurrection of a Frank Lloyd Wright legacy is the work of a team of Oak Park detectives.: Renovation Frank Lloyd Wright's legacy will rise again". Chicago Tribune. p. S_A1. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 172590369.

- ^ a b c d e Hoffmann 1984, p. 19.

- ^ Connors 1984, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Baer, Susan (January 24, 1978). "Tempo". Chicago Tribune. pp. 2.1, 2.2. ISSN 1085-6706. Retrieved January 23, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Connors 1984, p. 46.

- ^ a b c Hoffmann 1984, p. 21.

- ^ a b c Hoffmann 1984, p. 27.

- ^ a b Hoffmann 1984, p. 28.

- ^ a b Hoffmann 1984, p. 29.

- ^ a b Hoffmann 1984, p. 31.

- ^ a b Hoffmann 1984, pp. 32–33.

- ^ a b Connors 1984, pp. 59–60.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Smith 2008, p. 7.

- ^ a b c d Rodkin, Dennis (June 29, 2023). "What's That Building? Chicago Icons: Robie House". WBEZ. Retrieved January 24, 2025.

- ^ a b c d The Prairie School Review 1967, p. 10.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Sullivan, Barbara (November 4, 1984). "Wright's Robie House: 75 years, and still shining". Chicago Tribune. p. 308. ISSN 1085-6706. Retrieved January 24, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f Hoffmann 1984, p. 89.

- ^ a b c d Lucas 2006, p. 10.

- ^ a b c d e f g Pitz, Marylynne (November 6, 2010). "Restoring a Wright". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. pp. C1, C3. Retrieved January 27, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c Gill 1987, p. 195.

- ^ Robie, Frederick C. Jr. (March 29, 1957). "Voice of the People: the Robies Comment on Robie House". Chicago Daily Tribune. p. 14. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 180089035.

- ^ "Forced to Wall by Honor Debts: Fred C. Robie, Who Assumed Obligations of Excelsior Supply Co., Files Petition. Liabilities Are $591,805. Schedules Residence as Part of Assets to Pay Bills He Stood Good for". Chicago Daily Tribune. June 25, 1913. p. 15. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 173711781; "Director Bankrupt for Company's Debt". The Inter Ocean. June 25, 1913. p. 7. Retrieved January 24, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g Smith 2008, p. 9.

- ^ a b c d e f Hoffmann 1984, p. 90.

- ^ "Obituary". The Inter Ocean. October 24, 1912. p. 2. Retrieved January 24, 2025 – via newspapers.com; "David Lee Taylor Is Dead". Chicago Tribune. October 23, 1912. p. 2. ISSN 1085-6706. Retrieved January 24, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Realty Deals of Week Reviewed". The Inter Ocean. November 24, 1912. p. 24. Retrieved January 24, 2025 – via newspapers.com; "Chicago Apartment Is Part of $300,000 Deal at Evanston". Chicago Examiner. November 26, 1912. p. 16. Retrieved January 24, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c Hoffmann 1984, p. 91.

- ^ For the Chicago Dramatic Society meeting, see, for example: "Society and Entertainments". Chicago Tribune. May 6, 1919. p. 21. ISSN 1085-6706. Retrieved January 24, 2025 – via newspapers.com and "Music and the Stage". The Inter Ocean. March 13, 1913. p. 6. Retrieved January 24, 2025 – via newspapers.com. For the Quadranglers meeting, see "What Society People Are Doing". The Inter Ocean. February 7, 1914. p. 4. Retrieved January 24, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Hoffmann 1984, pp. 91–92.

- ^ a b c Hoffmann 1984, p. 92.

- ^ a b Hoffmann 1984, pp. 92–94.

- ^ Bargelt, Louise (June 20, 1926). "Designed Serve Needs Two Families: All Appearances of Single Residence". Chicago Daily Tribune. p. B7. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 180704589.

- ^ a b c d e Hoffmann 1984, p. 94.

- ^ a b c d e Smith 2008, p. 11.

- ^ a b Hansen, Harry (October 12, 1941). "First Reader". The Pittsburgh Press. p. 23. Retrieved January 25, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b The Prairie School Review 1967, pp. 10–11.

- ^ "Zone Board OK's Diamond Tool Shop on S. Side". Chicago Tribune. December 14, 1952. p. 9. ISSN 1085-6706. Retrieved January 25, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c "Plan Seminary Dormitory for Married Folk". Chicago Daily Tribune. March 2, 1957. p. 7. ISSN 1085-6706. Retrieved January 20, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Lister, Walter (March 19, 1957). "Frank Lloyd Wright Fights To Save '06 House He Built". New York Herald Tribune. p. 12. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1326293280.

- ^ "Laymen Vow to Promote Church Work". Chicago Tribune. May 28, 1956. p. 14. ISSN 1085-6706. Retrieved January 25, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Smith 2008, p. 12.

- ^ a b c Smith 2008, p. 13.

- ^ a b c Fuller, Ernest (March 12, 1957). "Fraternity Acts to Save Home Wright Designed". Chicago Daily Tribune. p. 26. ISSN 1085-6706. Retrieved January 20, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e Smith 2008, p. 15.

- ^ a b c "Wright Terms Doomed Robie House Sound, Hits Plan to Raze Structure: Only Kitchen is Out of Date, He Finds". Chicago Daily Tribune. March 19, 1957. p. B10. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 180080335.

- ^ a b c "Frank Lloyd Wright Fights to Save His 1906 Creation". The Grand Rapids Press. March 13, 1957. p. 5. Retrieved January 20, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Smith 2008, pp. 12–13.

- ^ "Save the Robie House, German Artists Urge". Chicago Daily Tribune. March 28, 1957. p. 3. ISSN 1085-6706. Retrieved January 20, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Realty Notes". Chicago Tribune. June 15, 1957. p. 39. ISSN 1085-6706. Retrieved January 20, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d Smith 2008, p. 14.

- ^ Gill 1987, p. 494.

- ^ a b c Fitzpatrick, Thomas (March 21, 1965). "Doom Haunts Wright's Robie House: Only a Fifth of Aid Fund Is in Hand". Chicago Tribune. p. B1. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 179834555.

- ^ a b c d Pippert, Wesley G. (May 8, 1965). "Chances Grow for Saving Wright's Robie House, Landmark in Chicago". The Wichita Beacon. United Press International. p. 2. Retrieved January 23, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Horne, Louther S. (April 15, 1957). "House by Wright Appears Doomed; Chicago Seminary Firm on Plan to Raze Robie Home Despite Pleas to Save It Wright Would Waive Fee". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 20, 2025.

- ^ a b c "Robie House Recognized as Landmark". Wisconsin State Journal. April 22, 1957. p. 8. Retrieved January 20, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c "Prototype of American Homes to Be Saved From Demolition". The Columbia Record. January 2, 1958. p. 26. Retrieved January 20, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Robie House Aided; Chicago Board Names Doomed Wright Home a Landmark". The New York Times. April 22, 1957. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 20, 2025.

- ^ "Three Named to Help Save Robie House". Chicago Daily Tribune. July 3, 1957. p. 22. ISSN 1085-6706. Retrieved January 20, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c "New York Builder Offers $125,000 for Robie House". Chicago Daily Tribune. December 21, 1957. p. 9. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 180275528.

- ^ a b c "Wright Building Saved; Zeckendorf Will Pay $125,000 for Doomed Robie House". The New York Times. December 21, 1957. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 20, 2025.

- ^ "Famed Robie House's Fate Up to City Council". Chicago Tribune. July 18, 1958. p. 5. ISSN 1085-6706. Retrieved January 20, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Urge Rezoning of Land Near Robie House". Chicago Daily Tribune. August 19, 1958. p. 2. ISSN 1085-6706. Retrieved January 20, 2025 – via newspapers.com; "Robie House Saved". The La Crosse Tribune. Associated Press. August 20, 1958. p. 17. Retrieved January 20, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Saarinen, Aline B. (April 19, 1959). "Preserving Wright Architecture; Steps Must Be Taken To Assure Future Of His Buildings". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 21, 2025.

- ^ a b c Smith 2008, p. 16.

- ^ a b "Robie House Restoration to Commence in Month: $250,000 Goal Set for Repairs of Monument". Chicago Tribune. April 18, 1965. p. SA2. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 179885236. Retrieved January 23, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Murtagh, William J. (April 1960). "Something Worth Saving: the National Trust and Our Heritage". Americas. Vol. 12, no. 4. p. 8. ProQuest 1792717068.

- ^ "Propose Robie House Use as Mayor's Home". Chicago Tribune. February 7, 1959. p. 11. ISSN 1085-6706. Retrieved January 20, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Truit, Richard (September 21, 1958). "Woman Urges Revival of Hyde Pk. Art Center: Former Headquarters of Art Colony". Chicago Daily Tribune. p. S1. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 182127102.

- ^ Philbrick, Richard (April 4, 1962). "U. Of Chicago May Take Over Robie House: Wright Masterpiece Adjoins Campus". Chicago Daily Tribune. p. 6. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 183124559. Retrieved January 23, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Philbrick, Richard (June 9, 1962). "U. Of C. Given F. L. Wright's Robie House: Plan to Restore Famed Building". Chicago Daily Tribune. p. C9. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 183190983. Retrieved January 23, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Drive Begun to Restore Robie House: National Campaign to Seek $250,000". Chicago Daily Tribune. August 21, 1962. p. A6. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 182979504. Retrieved January 23, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Landmark Saved". The Decatur Daily Review. Associated Press. August 21, 1962. p. 4. Retrieved January 23, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f Huff, Mary (September 9, 1962). "Robie House Restoration Is Campaign Goal". Chicago Tribune. pp. 8.1, 8.10. ISSN 1085-6706. Retrieved January 23, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e Sembower, John F. (August 21, 1964). "Quarter Million Dollars Needed to Repair Structure That Cost Only $40,000 to Build". Republican and Herald. p. 9. Retrieved January 23, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "International Group Seeks Funds to Restore Robie House in Chicago". The New York Times. February 2, 1963. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 23, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e Nelson, Robert (February 19, 1963). "Posterity Gets Robie House: Chicago Gem". The Christian Science Monitor. p. 4. ISSN 0882-7729. ProQuest 510486661.

- ^ a b Philbrick, Richard (February 5, 1963). "U. C. Deeded Robie House; Drive Begins". Chicago Daily Tribune. p. 23. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 182577323. Retrieved January 23, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c The Prairie School Review 1967, p. 12.

- ^ a b Philbrick, Richard (February 3, 1963). "Seek $250,000 to Restore Robie House: U. of C. to Accept Zeckendorf's Gift of Deed". Chicago Tribune. p. 12. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 182613024.

- ^ a b The Prairie School Review 1967, p. 14.

- ^ a b "The House That Wright Built". Democrat and Chronicle. June 20, 1965. p. 71. Retrieved January 23, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Student Tours of Robie House Are Started". Chicago Tribune. April 8, 1963. p. 19. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 182674875.

- ^ "$31,000 Gifts in Robie House Project Bared". Chicago Tribune. August 15, 1963. p. D14. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 182790787.

- ^ "Fund for the Robie House Of Wright Is Given $10,000". The New York Times. June 6, 1964. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 23, 2025.

- ^ "Robie House to Be Sealed Up for Winter". Chicago Tribune. October 17, 1963. p. C15. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 179312883.

- ^ a b Buck, Thomas (January 5, 1964). "Robie House Restoration Fund Is Short $210,000". Chicago Tribune. p. B10. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 179358135.

- ^ a b c "Dedicated as U.S. Landmark". The Belleville News-Democrat. Associated Press. April 2, 1964. p. 19. Retrieved January 23, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Starr, Frank (May 14, 1964). "Robie House Tours Teach History, Art". Chicago Tribune. p. S1. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 179468611. Retrieved January 23, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c Hoffmann, Donald L. (August 22, 1963). "Seek to Save Architectural Masterpiece". The Kansas City Times. p. 12. Retrieved January 23, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b National Park Service 1966, p. 5.

- ^ a b "Robie House Restoration Underway" (PDF). Progressive Architecture. Vol. 46, no. 10. October 1965. pp. 55, 57.

- ^ a b "Wright's Robie House to Be Open Sundays". Chicago Tribune. May 23, 1965. p. 18. ISSN 1085-6706. Retrieved January 23, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Robie House Job Waits for Money". Chicago Tribune. June 5, 1966. p. 4. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 178999465. Retrieved January 23, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Nolte, Robert (July 8, 1965). "Robie House Repairs Near Mid-way Point". Chicago Tribune. p. 3. ISSN 1085-6706. Retrieved January 23, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Federal Program To Save Historic Chicago: Famous Houses To Be Restored, Preserved". Chicago Daily Defender. August 24, 1966. p. 4. ProQuest 494237948.

- ^ "Name World Affairs Site for Stevenson: Will Be Located in Robie House". Chicago Tribune. July 15, 1966. p. C13. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 178999484; "U.N. Told of Center to Honor Stevenson". The New York Times. July 15, 1966. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 23, 2025.

- ^ a b The Prairie School Review 1967, p. 15.

- ^ The Prairie School Review 1967, pp. 15–16.

- ^ a b The Prairie School Review 1967, pp. 16–17.