Ali Kosh

32°33′28.13″N 47°19′29.72″E / 32.5578139°N 47.3249222°E

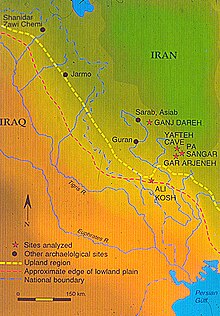

Map showing location of Ali Kosh and other locations of early herding activity | |

Neolithic sites in Iran | |

| Location | Ilam province |

|---|---|

| Region | Iran |

| Diameter | 135 m |

| History | |

| Founded | c. 7500 BC |

| Cultures | Pre-Pottery Neolithic |

| Site notes | |

| Discovered | 1960s |

| Archaeologists | |

Ali Kosh is a small Tell of the Early Neolithic period located in Ilam province in west Iran, in the Zagros Mountains.[1] It was excavated by Frank Hole and Kent Flannery in the 1960s.[2]

Site

[edit]The site is about 135 m in diameter.[3]

Research has found three phases of occupation of the site. The exact length of the occupation is debated; earlier authors saw the site as inhabited over an almost 2,000 year period, starting from about 9,500 years ago (7500 BCE).[3] But recent (2018) analysis indicates only a 1000-year occupation.[4]

The site was occupied originally by pre-pottery peoples.[5] Pottery was introduced to Ali Kosh during the third phase of its occupation. Nearby Chogha Sefid has only one pre-pottery phase, after which the occupation extended into the Chalcolithic period.[6]

Occupational phases

[edit]

Three phases of occupations have been identified.

Bus Mordeh phase

[edit]Bus Mordeh phase started around 7500 BC.[4] The settlement began as a group of small, rectangular houses with several rooms made of rammed earth. The occupants develop an economy based on the herding of sheep, goats, hunting and gathering wild plants.

Ali Kosh phase

[edit]This phase is dated around 7250-7000 BC. With larger houses, the deceased are buried under the house floors, sometimes with various burial gifts. The skull deformation using bandages during childhood is introduced, possibly as a sign of the different status of the bearers. The economy shows a more intense agricultural base supported by fishing and shell-fishing as a complement to the diet.

Mohammed Jaffar phase

[edit]This phase is dated 7000-6500 BC.[4] The houses are made of stone and a necropolis is established in the nearby area. The tools are made of flint, with some obsidian use. Polished stone containers, hand mills, mortars, and baskets (sometimes lined with pitch) are in use. Ceramics appeared at the site during this period around 7000 B.C; decorated vases, and human and animal figurines are produced.[4] Some materials are imported from other areas, such as copper, and turquoise. There are also other links with the contemporary cultures of the Middle East. During the summer, the herds are moved to the grazing areas in the highland areas.

The settlement was no longer occupied after this time.

Earliest agriculture

[edit]Ali Kosh was the earliest agricultural community in western Iran, where emmer was already cultivated in the eighth millennium BC. This crop was not native to the area. Wild two-row hulled barley was also present. Goats and sheep were also herded.[7]

Similar site on the Deh Luran plain is Chogha Sefid, and also Tepe Abdul Hosein in Luristan. All three have similar stone tools. Ganj Dareh in Luristan (seen on the map), also similar, is even somewhat older than these.[7][6]

Genetic analysis

[edit]Human remains from the area have been analyzed in 2016 for their ancestry. Researchers sequenced the genome from a 30-50-year-old woman from Ganj Dareh. mtDNA analysis shows that she belonged to Haplogroup X (mtDNA).[8]

Skull modification

[edit]In 2017, several skeletons were found by archaeologists in Ali Kosh. 7 crania were found, all showing the evidence of ritual cranial deformation.

- "The most striking feature of all crania was their more or less pronounced artificial deformation that was evident in spite of post-mortem alteration and fragmentation of all crania. In all cases circumferential modification was evident,[9] resulting from application of a band wrapped around the cranium ... Artificial cranial deformation was common in the Near East and especially in Iran during the Neolithic and Chalcolithic[10]..."[11]

Previously, similar crania were already excavated in the area by Hole and Flannery.[12]

Ritual tooth avulsion

[edit]Another unusual cultural practice observed by researchers in these skulls was the ritual front tooth avulsion (removal of one or more teeth). Such a practice was quite common around the world in ancient times.[13]

- "Another cultural modification of the head observed at Ali Kosh was avulsion of the upper right first incisor in all adult males, but not in children nor adolescent individuals. ... Tooth avulsion was common during the Early Holocene in North Africa,[14] and it was also occasionally observed in the Natufian culture ..."[15]

According to these researchers, such a custom has not been previously reported for the eastern part of the Fertile Crescent.[15]

Relative chronology

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Hole, Frank (10 October 2011). "Ali Kosh". Yale Campus Press. Yale University. Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- ^ Darvill, Timothy (2008). The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Archaeology (2nd ed.). Oxford Reference. doi:10.1093/acref/9780199534043.001.0001. ISBN 9780191727139.

- ^ a b Smith, Andrew Brown (2005). African herders: emergence of pastoral traditions. Rowman Altamira. pp. 67–68. ISBN 978-0-7591-0748-9.

- ^ a b c d Darabi, H. (2018). 'Revisiting Stratigraphy of Ali Kosh, Deh Luran Plain', Pazhoheshha-ye Bastan shenasi Iran, 8(16), pp. 27-42. doi:10.22084/nbsh.2018.14908.1661

- ^ Langer, William L. (1972). An Encyclopedia of World History (5th ed.). Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company. p. 17. ISBN 0-395-13592-3. LCCN 72186219.

- ^ a b Frank Hole (2004), NEOLITHIC AGE IN IRAN Archived 2012-10-23 at the Wayback Machine iranicaonline.org

- ^ a b Mukhtar Ahmed, Ancient Pakistan – An Archaeological History: Volume II: A Prelude to Civilization. 2014, pp.214-215

- ^ Gallego-Llorente, M.; et al. (2016). "The genetics of an early Neolithic pastoralist from the Zagros, Iran". Scientific Reports. 6: 31326. Bibcode:2016NatSR...631326G. doi:10.1038/srep31326. PMC 4977546. PMID 27502179.

This article contains quotations from this source, which is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) license.

This article contains quotations from this source, which is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) license.

- ^ Frieß & Baylac 2003

- ^ Meiklejohn et al. 1992; Daems & Croucher 2007

- ^ Arkadiusz Sołtysiak*1, Hojjat Darabi, Human remains from Ali Kosh, Iran, 2017. Bioarchaeology of the Near East, 11:76–83 (2017) Short fieldwork report.

- ^ Hole F., Flannery K.V., Neely J.A. (1969), Prehistory and human ecology of the Deh Luran plain. An early village sequence from Khuzistan, Iran, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan.

- ^ Pinchi, Vilma; Barbieri, Patrizia; Pradella, Francesco; Focardi, Martina; Bartolini, Viola; Norelli, Gian-Aristide (2015). "Dental Ritual Mutilations and Forensic Odontologist Practice: a Review of the Literature". Acta Stomatologica Croatica. 49 (1): 3–13. doi:10.15644/asc49/1/1. ISSN 0001-7019. PMC 4945341. PMID 27688380.

- ^ Stojanowskiet al. 2014; De Groote & Humphrey 2016

- ^ a b Arkadiusz Sołtysiak, Hojjat Darabi, Human remains from Ali Kosh, Iran, 2017. Bioarchaeology of the Near East, 11:76–83 (2017) Short fieldwork report.

Bibliography

[edit]- F. Hole and K. V. Flannery, The Prehistory of Southwestern Iran: A Preliminary Report, Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 33, 1968

- F. Hole, K. V. Flannery, and J. A. Neely, Prehistory and Human Ecology of the Deh Luran Plain. Memòria 1, Ann Arbor, 1969.

- F. Hole, Studies in the Archeological History of the Deh Luran Plain. Memòria 9, Ann Arbor, 1977