Temple Sinai (Oakland, California)

| Temple Sinai | |

|---|---|

The synagogue building, in 2008 | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Reform Judaism |

| Ecclesiastical or organisational status | Synagogue |

| Leadership |

|

| Status | Active |

| Location | |

| Location | 2808 Summit Street, Oakland, California 94609 |

| Country | United States |

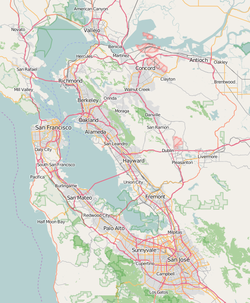

Location in San Francisco Bay Area, California | |

| Geographic coordinates | 37°49′00″N 122°15′52″W / 37.81667°N 122.26444°W |

| Architecture | |

| Architect(s) | G. Albert Lansburgh (1914) |

| Type | Synagogue architecture |

| Style | Beaux-Arts (1914) |

| Date established | 1875 (as a congregation) |

| Groundbreaking | 1913 |

| Completed |

|

| Construction cost | $100,000 (today $3 million)[1] |

| Specifications | |

| Dome(s) | One |

| Materials | Pressed brick, carved wood |

| Designated | 1995 |

| Reference no. | 118 |

| Website | |

| oaklandsinai | |

| [2][3][4][5][6][7] | |

Temple Sinai (officially the First Hebrew Congregation of Oakland[8]) is a Reform Jewish congregation and synagogue located at 2808 Summit Street (28th and Webster Streets) in Oakland, California, in the United States. Founded in 1875, it is the oldest Jewish congregation in the East San Francisco Bay region.[9][10]

Its early members included Gertrude Stein and Judah Leon Magnes, who studied at Temple Sinai's Sabbath school, and Ray Frank, who taught them. Originally traditional, the temple reformed its beliefs and practices under the leadership of Rabbi Marcus Friedlander (1893–1915). By 1914, it had become a Classical Reform congregation.[11][12][13] That year the current sanctuary was built: a Beaux-Arts structure designed by G. Albert Lansburgh, which is the oldest synagogue building in Oakland.[4]

The congregation weathered four major financial crises by 1934. From then until 2011, it was led by just three rabbis, William Stern (1934–1965), Samuel Broude (1966–1989), and Steven Chester (1989–2011).[11][14]

In 2006 Temple Sinai embarked on a $15 million capital campaign to construct an entirely new synagogue campus adjacent to its current sanctuary.[15] Groundbreaking took place in October 2007,[16] and by late 2009 the congregation had raised almost $12 million towards the construction.[17] As of 2015, Temple Sinai had nearly 1,000 member families.[16] The rabbis were Jacqueline Mates-Muchin and Yoni Regev, and the cantor was Ilene Keys.[2] The synagogue has two emeritus rabbis, Samuel Broude (1924-2020) and Steven Chester.

Early years

[edit]Founded in 1875 as the First Hebrew Congregation of Oakland, Temple Sinai is the oldest synagogue in the East Bay region of the San Francisco Bay Area.[9][10] It grew out of Oakland's Hebrew Benevolent Society, which had been organized in 1862 by eighteen merchants and shopkeepers from several foreign countries—predominantly Polish Jews from Poznań.[18] Although Hebrew Benevolent Societies typically ceased operations upon the founding of a synagogue, Oakland's was unusual in continuing to function independently for a number of years (the two groups did not merge until 1881).[19]

By 1876, the congregation had purchased land on the south side of 14th and Webster streets; however, due to a severe recession in California at the time, the congregation did not construct a building until 1878.[9] The wooden structure, with Moorish Revival elements and onion domes, was completed at a cost of around $8,000 (today $253,000).[20]

Services were initially traditional, following the Polish rite. Men and women sat separately, but the mehitza separating them was soon done away with. In 1881 the new president, David Hirschberg, led a campaign to modernize, and convinced a small majority to introduce a number of reforms, including the addition of a mixed choir of Christians and Jews and organ music, and the removal of the requirement for a minyan.[18] Traditionalists—who mostly came from the Hebrew Benevolent Society—objected and withdrew, forming their own Orthodox minyan, which eventually became Oakland's Congregation Beth Jacob.[21]

Levy, Sessler eras: 1881–1892

[edit]In 1881, the congregation hired Oakland's first rabbi, Meyer Solomon Levy. Born in England in January 1852 and raised there, he was the son of Rabbi Solomon Levy of Borough Synagogue in London.[22] Meyer Solomon Levy had been ordained in England as an Orthodox rabbi before he was twenty, and moved to Australia as a young man.[23] An early supporter of Zionism,[24][25] he had served as a rabbi in Melbourne before moving to California in 1872[22] or 1873,[24] where he served as the rabbi of Temple Emanu-El (then Bickur Cholim) in San Jose.[23] Levy was paid $100 a month (today $3,160), and donated a percentage to the poor.[26]

Levy came into conflict with Oakland's public schools, which refused to excuse Jewish students on High Holy Days. He petitioned that they be excused, but the superintendent and district went even further, and directed teachers not to schedule examinations for those days.[26] Although sensitive to the needs of the members, Levy was more observant than his congregants, which also led to conflict. He accepted the reforms of shortening the Shabbat services, and facing the congregation (rather than the ark) during prayer, but he successfully resisted attempts to adopt Isaac Mayer Wise's 1885 "Minhag America" Prayer-Book.[27]

Although traditional in some ways, Levy was progressive in others. "Deeply affected by the enlightened spirit of his day", according to historian Fred Rosenbaum, he "delivered lectures with titles such as 'Progress of Science' and, while at the First Hebrew Congregation, he invited Oakland's Unitarian minister to give a series of talks at the synagogue. Levy in turn was well received at the Unitarian Church, where he spoke on the theory of evolution."[25]

In 1885, the synagogue burned down, although the Torah scrolls were saved by a congregant who entered the burning building to retrieve them. Levy made prodigious efforts to raise funds for a new building, traveling as far away as Vancouver. The synagogue's female members also raised significant funds through a "Grand Fair". Their combined efforts were successful, and by 1886 a new building had been erected at 13th and Clay streets.[28] The structure had "Moorish elements inspired by Isaac Mayer Wise's Plum Street Temple in Cincinnati".[26]

The tensions between liberal-minded members and the traditional Levy were never resolved, and in 1891, the rabbi moved to San Francisco's Congregation Beth Israel.[27] That year the women of the congregation formed the Ladies Auxiliary (Temple Sisterhood), whose initial mandate was to assist the work of the synagogue's Sunday school, and increase its enrollment.[6]

During Levy's tenure, the synagogue had several congregants who were famous, or would become so. Ray Frank, the first Jewish woman to preach formally from a pulpit in the United States, settled in Oakland around 1885, and taught Hebrew Bible studies and Jewish history at First Hebrew Congregation's Sabbath school,[12][29] where she was superintendent.[30] Her students there in the 1880s included Gertrude Stein, later to become a famous writer, and Judah Leon Magnes, who would become a prominent Reform rabbi.[12][31] Magnes's views of the Jewish people were strongly influenced by First Hebrew's Rabbi Levy,[24] and it was at the building on 13th and Clay that Magnes first began preaching—his bar mitzvah speech of 1890 was quoted at length in The Oakland Tribune.[13]

Morris Sessler succeeded Levy as rabbi in 1892. He had served at Congregation of the Sons of Israel and David in Providence, Rhode Island, from 1887 to 1892.[11][32] His tenure lasted only six months, as "his ideas did not harmonize with those of the congregation".[33] He became rabbi of Congregation Gates of Prayer in New Orleans that same year, where he served until 1904.[34]

Friedlander, Franklin eras: 1893–1919

[edit]

The congregation hired Marcus Friedlander of Congregation Baith Israel in Brooklyn, New York in 1893. Soon after he was hired, California experienced another economic downturn, which hurt the finances of members of the congregation. The congregation sold its property at 13th and Clay (which had become the heart of the business district) in 1895, and moved to a less expensive location at the northwest corner of 12th and Castro streets, and renovated the building there in 1896.[5] Over 500 people, both Jews and non-Jews, were sheltered in the building for days after the 1906 San Francisco earthquake.[35] The synagogue had 95 members by 1907,[36] with annual revenues of $6,000 (today $196,000).[37]

Friedlander and former congregation president Abraham Jonas persuaded the congregation to introduce a number of significant reforms in the service: they first adopted the Jastrow prayer book, and later the Reform movement's Union Prayer Book (though in a revised, less radical version published specifically for First Hebrew, and authorized by the Central Conference of American Rabbis).[5][38] By 1908, the congregation had eliminated the second day of Rosh Hashanah, and few men wore head coverings in the service,[5] and by 1914 the congregation had moved completely to the radicalism of "Classical Reform".[13]

In 1910, First Hebrew bought a lot on Telegraph Avenue at Sycamore Street, near 26th Street, for $28,000 (today $920,000), and sold its property at 12th and Castro for the same amount. The congregation, however, decided not to build there. In 1912 it found a better location, and purchased its current site at 28th and Webster for $12,050 (today $390,000).[39] Groundbreaking took place on October 26, 1913, and the building was completed there in 1914 at a cost of $100,000 (today $3 million).[3][39] Fourteen thousand dollars (today $440,000) of the costs were raised by the Ladies Auxiliary, which also purchased a new Austin pipe organ for the sanctuary at a cost of $5,000 (today $150,000).[6][40] The new building was called "Temple Sinai", and thereafter the congregation itself became known as "Temple Sinai", although it retained the official name of "First Hebrew Congregation of Oakland".[8]

Designed by noted American architect G. Albert Lansburgh, the Beaux-Arts structure had six tall stained glass windows, an "elliptical dome", and an entrance characterized by "graceful Corinthian columns supporting a Greco-Roman portico".[7] Carved into the entablature above the entrance was the Biblical verse "MY HOUSE SHALL BE CALLED A HOUSE OF PRAYER FOR ALL PEOPLE" (Isaiah 56:7).[3][41] More modest in size than most Beaux-Arts buildings, it nevertheless had features typical of that style, including its "cross-axial composition". However, it was adorned with "simpler materials such as pressed brick and carved wood", rather than the usual "florid Classical design elements". Along with the sanctuary, the building included a social hall and classrooms.[4] It is the only example of Lansburgh's work in Oakland, and one of about 150 Oakland buildings given an "A" or "Highest Importance" rating by the Oakland Cultural Heritage Survey, which signifies "outstanding architectural example or extreme historical importance".[42] The building has a status code of "3S" in the California Historical Resource Information System database, indicating that it "appears eligible for the National Register of Historic Places" (NRHP).[43]

The outbreak of World War I, and the costs of the new mortgage, placed a significant financial strain on the members, and in 1915 they decided to release Friedlander from his contract.[5][16] Temple Sinai hired Harvey B. Franklin as rabbi in 1917, but his tenure there was only two years.[5] During his term, the congregational school held classes twice a week, and had 285 students and 8 teachers.[44] Franklin next served at Bickur Cholim in San Jose—the congregation from which Temple Sinai's first rabbi, Myer Solomon Levy, had come.[45]

Coffee era: 1921–1933

[edit]After going without a rabbi for another two years, in 1921 Temple Sinai hired Rudolph I. Coffee, an Oakland native and cousin of Judah Leon Magnes.[16] Coffee was outspoken, and passionately advocated liberal causes: he supported disarmament, birth control, and separation of church and state, and opposed prohibition, antisemitism, and Tammany Hall.[5] Along with other local rabbis Jacob Nieto and Jacob Weinstein, he demanded the release of labor leaders and accused bombers Thomas Mooney and Warren Billings.[46] He also supported California's compulsory sterilization of the mentally ill and mentally retarded, and eugenicist E. S. Gosney's advocacy on this issue.[47]

Coffee was involved in the California State Prison System, and during his tenure at Temple Sinai he was head of the Jewish Committee of Personal Service, a California-wide organization that "ministered to Jews in state prisons". In January 1924, California's governor appointed Coffee to the State Board of Charities and Corrections, which was responsible for supervising California's state prisons.[48]

In 1931, Coffee opposed California legislation intended to regulate the kosher food industry and prohibit fraudulent claims that foods were kosher. In a letter to state senator E.H. Christian he stated:

I am unalterably opposed to this bill because Judaism need not call upon the State to settle its own internal affairs. We are starting a dangerous precedent in California which can only lead to evil consequences.

Four years ago you assisted in preventing an increase of "wine rabbis." The law relative to sacramental wine was properly surrounded, and California Jews do not suffer the disgrace which eastern brethren feel.

This will bring a "meat rabbi" into existence. New York state has this kosher law and yet it did not prevent the terrible scandal which was uncovered last month in New York City. Use your best influence to prevent it.

If Judaism has not enough inner resources to meet present day conditions, the sooner it passes away the better.

Despite Coffee's opposition, the legislation was enacted.[49]

Coffee's advocacy, and Temple Israel's financial instability, eventually contributed to his dismissal from Temple Sinai in 1933; at the same time that the membership was experiencing financial distress due to the Great Depression, Coffee was advocating higher salaries for government employees.[50] After leaving Temple Sinai, he became chaplain at San Quentin State Prison.[48]

Stern era: 1934–1965

[edit]In 1934, Temple Sinai hired William M. Stern (originally Sternheser) as rabbi.[5] A San Francisco native and son of an Orthodox rabbi, he had been persuaded by Rabbi Martin Meyer of the Reform Congregation Emanu-El to attend Hebrew Union College (HUC), where Stern received his ordination. He served as rabbi at a number of Southern and Midwestern synagogues in the 1920s and early 1930s.[51]

Much less formal than his predecessor Coffee, Stern was seen as a poker-playing, cigar-smoking "regular guy",[16] and he focused on combating the spread of antisemitism.[5] His wife Rae was also very active in the congregation. She taught at the synagogue's Hebrew school, and led the sisterhood.[52]

Although originally anti-Zionist, Stern's views changed in the 1940s, and by 1942 he was strongly supported Jewish nationalism.[53] When an Oakland branch of the anti-Zionist American Council for Judaism formed in 1944, Stern opposed its creation, even though many members, including its president, were leading members of Temple Sinai.[54] By 1948, however, the congregation had also become supportive of Zionism.[5]

During Stern's tenure Temple Sinai expanded its facilities, adding a religious school building, offices, and a chapel in 1947–1948, and moving the main entrance to Summit Street.[55] The main building's interior was also significantly remodeled, aside from the sanctuary.[40] The congregation also built the Temple House (called Covenant Hall), in 1950.[5] The following year the synagogue put on an exhibition called "Arts in Action", "that included sculptors, weavers, filmmakers, ceramists, and others." The event's director asked poet, artist and art critic Weldon Kees to jury a show of paintings; Kees ended up having to find the paintings as well. When the Temple's board saw the selected works, they did not want display all of them, but acquiesced after "a strong protest".[56]

In 1965, the congregation bought land in Oakland Hills, anticipating a future move.[14] In December of that year Stern died unexpectedly.[57] Following his death, Temple Sinai held for many years an annual Stern Lecture series in his memory.[58]

Broude era: 1966–1989

[edit]In 1966, the congregation hired Samuel Broude as rabbi. A graduate of the University of Chicago, in the late 1940s he had worked in Pasadena at a Reconstructionist synagogue, as a part-time cantor and Hebrew teacher, and then in the early 1950s as cantor of Reform University Synagogue of Los Angeles. After completing his rabbinic training, he became associate rabbi at Congregation Ansche Chesed in Cleveland, where he served under Rabbi Arthur Lelyveld for six years before coming to Temple Sinai.[59]

Like Temple Sinai's previous rabbis, Broude passionately supported liberal causes, opposing U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War, and taking part in marches during the Civil Rights Movement. Although he was a Reform rabbi, he had gone to an Orthodox yeshiva as a boy, and religiously he was in many ways more traditional than his predecessors.[60] He re-introduced ritual into the synagogue, but more contentiously opposed intermarriage. His immediate predecessor, Stern, had officiated at intermarriages "under certain conditions". Broude initially did so as well, under "extenuating circumstances" (e.g. if the bride were pregnant). His position later hardened, and he refused to perform such marriages under any circumstances. He even refused to allow other rabbis who would be willing to do so officiate at intermarriages at Temple Sinai. The issue eventually came to a congregational vote in 1972, which supported Broude, although the debate was never completely settled.[61]

Broude was, however, not opposed to all religious innovations. Under his leadership, Temple Sinai began holding monthly fine arts performances as part of the Friday night service, in place of the usual sermon. In December 1970, the Temple's fine arts committee commissioned an original dance work from Anna Halprin and her multi-racial dance troupe. For the next two months Broude met weekly with Halprin, educating her regarding the Friday night prayers.[62] The completed work, titled Kadosh, included a candlelight vigil, and dancers tearing their clothes and shouting questions at Broude that reframed the classic question about God and The Holocaust in terms of the Vietnam War: "How can there be a God if He allows all the suffering of the Vietnam War to continue?"[63] The performance engendered passionate responses from the congregation; according to Broude "I don't know if anyone was neutral. Half thought it was fantastic, half thought it was terrible!"[64]

Broude also argued that the congregation should remain in downtown Oakland, and in 1975, convinced them to stay. He retired in 1989, the year the buildings survived the Loma Prieta earthquake.[65] After his retirement from Temple Sinai he remained active, filling in at synagogues mostly in the Bay Area, and teaching. He also wrote an autobiography, and a one-man show based on it called "Listening for the Voice", which he performed at a number of East Bay synagogues, including, in 2009, at Temple Sinai.[66]

Rabbi Broude died on January 24, 2020, at the age of 95, three days after suffering a stroke at his wife, Judith's, funeral.[67]

Chester era: 1989–2011

[edit]

Steven Chester, a graduate of UCLA, and ordained by HUC in 1971, became rabbi in 1989.[14] He had previously served as rabbi of Temple Beth Israel in Jackson, Michigan, from 1971 to 1976, and Temple Israel in Stockton, California, from 1976 to 1989, where he was also an adjunct professor in the Religious Studies department of the University of the Pacific. Chester added a pre-school and adult education programs to the services offered by the synagogue, and supported the congregation's return to more traditional practices, including the re-introduction of Hebrew into the service. He also continued his predecessors' passion for social justice, taking up causes "from advocating for local affordable housing and health care for the disenfranchised to supporting women's reproductive rights and protesting the genocide in Darfur." In 2006, Chester was voted Reader's Choice for "Minister/Rabbi/Imam with the Biggest Heart" in the East Bay Express.[68]

The synagogue survived the Oakland firestorm of 1991 mostly unscathed,[14] although a number of congregants lost their homes.[16] Membership was over 640 families by 1993.[14] In 1994, the congregation again significantly remodeled the interior of the main building, aside from the sanctuary.[40] In December of that year, the building was designated a Historic Property by the City of Oakland.[42]

Temple Sinai has had three associate or assistant rabbis since 1998.[16] Andrea Berlin joined the synagogue as its first assistant rabbi in 1998, after being ordained at HUC in Cincinnati. From 2006 to 2008, she also served on the board of the Jewish Family and Children's Services of the East Bay.[69] Suzanne Singer joined Temple Sinai in 2003, after graduating from HUC in Los Angeles. Before becoming a rabbi, Singer had for two decades been a producer of television programs and documentaries, winning two Emmy Awards.[70] In 2005 she became interim rabbi of Temple Beth El of Riverside, California, and later its permanent rabbi.[71] Jacqueline Mates-Muchin, a San Francisco native, graduated from HUC in New York in 2002. She is the first Chinese-American rabbi in the world.[72][73] After serving as an assistant rabbi in Buffalo, New York, she joined Temple Sinai in 2005.[2][74]

To accommodate the large number of people attending on the High Holy Days, since 2001 Temple Sinai has held its main High Holy Day services at Oakland's NRHP-listed Art Deco Paramount Theater. While it still holds smaller High Holy Day services in the sanctuary at 2808 Summit Street, the main services at the Paramount fill the entire 1,800 seats on the mezzanine of the theater, and most of the 1,200 seats in the balcony.[75]

In 2006, the congregation embarked on a campaign to create a new campus for Temple Sinai, to be located adjacent to the existing sanctuary and social hall. The $15 million project included "new offices, a larger chapel, a kitchen upgrade, outdoor sacred space, a new preschool with six classrooms and a 4,500-square-foot playground ... 10 additional classrooms for Midrasha teens and adult education, an art room, library, teen lounge and expanded parking."[15] The L-shaped two-story school/office building would be 16,300 square feet (1,510 m2), and accommodate approximately 100 children in the pre-school. The 2,500-square-foot (230 m2) chapel, which would hold up to 250 people, would be an addition to the rear of the existing social hall.[76]

Groundbreaking took place in October 2007,[77] and the building was completed in 2010.[16] In order to accommodate the new buildings, the school and chapel built in the late 1940s were razed, along with two office buildings on adjoining lots purchased for the expansion. Nine portable buildings were installed on the campus of Merritt College in Oakland Hills to serve in the interim.[78] By December, 2009, Temple Sinai had raised almost $12 million from 651 households (70% of the congregation).[17]

Chester had planned to retire in June 2009, and the congregation embarked on a search for a new senior rabbi in 2008. Twenty-three candidates were narrowed down to one finalist, but in early December that individual informed the search committee that he was withdrawing his name from consideration.[79] While the search was progressing, Chester had realized that, due to the 2008 financial crisis, he would have to keep working. After the main candidate withdrew, the synagogue's president approached Chester, asking if he would stay on for another term, which Chester agreed to do.[80] Chester retired in June 2011, becoming (along with Broude) Rabbi Emeritus.[2]

Present era: 2011–2021

[edit]Andrew Straus joined Temple Sinai as senior rabbi in December 2011. A graduate of Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion (HUC), he had previously served as assistant rabbi of Peninsula Temple Sholom in Burlingame, California, Temple Beth Sholom of New City, New York, and most recently for 13 years as rabbi of Temple Emanuel of Tempe, Arizona. Rabbi Straus resigned his position in 2014 by mutual consent with the Board of Trustees. He joined Central Synagogue in New York City as Interim Rabbi for one year.[81]

In January 2015, Rabbi Mates-Muchin was overwhelmingly elected senior rabbi. As of 2014, Temple Sinai, the East Bay's oldest synagogue, had nearly 1,000 member families.[82] The full-time rabbis were Mates-Muchin and Yoni Regev, and the cantor was Ilene Keys.[2]

In 2017, antisemitic graffiti was written on the temple walls on Rosh Hashanah.[83]

Notable congregants

[edit]- Judah Leon Magnes, rabbi, first President of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Clergy, Temple Sinai website.

- ^ a b c Isaac (2009), p. 35.

- ^ a b c Palmer (2008), p. 4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Olitzky and Raphael (1996), p. 55.

- ^ a b c Voorsanger (1916), pp. 66–67.

- ^ a b See Isaac (2009), p. 35, Palmer (2008), p. 4 and Rosenbaum (2009), p. 89.

- ^ a b The name of the congregation is "First Hebrew Congregation of Oakland". The name of the current synagogue building is "Temple Sinai". See Olitzky and Raphael (1996), p. 55, Temple Sinai Bylaws, October 2006, Articles 1 and 2, and History of Temple Sinai (1875–2009), Temple Israel website.

- ^ a b c Olitzky and Raphael (1996), p. 54.

- ^ a b Bibel (2009).

- ^ a b c Olitzky and Raphael (1996), pp. 54–55.

- ^ a b c Rosenbaum (1987), p. 21.

- ^ a b c Rosenbaum (1987), p. 23.

- ^ a b c d e Olitzky and Raphael (1996), p. 56.

- ^ a b Pine (2008).

- ^ a b c d e f g h History of Temple Sinai (1875–2009), Temple Israel website.

- ^ a b Im Tirtzu: If you will it, it is no dream, Temple Sinai website.

- ^ a b See Olitzky and Raphael (1996), p. 54 and Rosenbaum (2009), p. 66.

- ^ Kahn (2002), p. 237.

- ^ See Kahn (2002), p. 240, Isaac (2009), p. 15 and Rosenbaum (1976), p. 7.

- ^ Rosenbaum (2009), pp. 66–67.

- ^ a b American Jewish Year Book Vol. 5, p. 75.

- ^ a b See Rosenbaum (2009), p. 66, Rosenbaum (1987), p. 22 and Isaac (2009), p. 15.

- ^ a b c Rosenbaum (1987), p. 22.

- ^ a b Rosenbaum (2009), p. 108.

- ^ a b c Isaac (2009), p. 15.

- ^ a b See Rosenbaum (2009), pp. 66 and 108, Rosenbaum (1987), p. 23 and Olitzky and Raphael (1996), p. 54

- ^ See Rosenbaum (1987), p. 23, Olitzky and Raphael (1996), p. 54 and Isaac (2009), p. 15.

- ^ Rosenbaum (2009), p. 121.

- ^ Taylor and Weir (2006), p. 90.

- ^ Rosenbaum (2009), pp. 67–68.

- ^ See Landman (1942), Vol. 8, p. 260 and Landman (1943), Vol. 9, p. 17.

- ^ According to Olitzky and Raphael (1996), pp. 54–55. Rosenbaum (1976), p. 45 writes similarly "A Rabbi Sessler of Providence, Rhode Island, succeeded him but lasted only six months in the Golden State; we know only that 'the ideas of the people here did not harmonize with his'."

- ^ Lachoff and Kahn (2005), p. 96.

- ^ Rosenbaum (2009), p. 173.

- ^ At the time only male heads of households were counted as members.

- ^ American Jewish Yearbook Vol. 9, p. 132.

- ^ Wachs (1997), p. 125.

- ^ a b See Voorsanger (1916), pp. 66–67 and Olitzky and Raphael (1996), p. 55.

- ^ a b c Palmer (2008), p. 7.

- ^ Rosenbaum (1976), p. 52.

- ^ a b Palmer (2008), p. 2.

- ^ Palmer (2008), p. 3.

- ^ American Jewish Year Book, Vol. 21, p. 440.

- ^ See Olitzky and Raphael (1996), p. 70 and Weissbach (2001).

- ^ Rosenbaum (2009), p. 129.

- ^ Kline (2005), p. 94.

- ^ a b Raphael (2008), p. 227.

- ^ American Jewish Yearbook, Vol. 73, pp. 35–37.

- ^ According to Olitzky and Raphael (1996), p. 55. According to Conmy (1961), p. 51, he "resign[ed] first to rest and later to participate in other Jewish activities."

- ^ Rosenbaum (2000), p. 130.

- ^ Isaac (2009), p. 55.

- ^ See Olitzky and Raphael (1996), p. 55 and Rosenbaum (2009), p. 315.

- ^ Rosenbaum (2009), p. 316.

- ^ See Olitzky and Raphael (1996), p. 55 and Isaac (2009), p. 59.

- ^ Reidel (2007), p. 251.

- ^ See Olitzky and Raphael (1996), p. 55 and Isaac (2009), p. 71.

- ^ Isaac (2009), p. 74.

- ^ See Pine (2010) and History of Temple Sinai (1875–2009), Temple Israel website.

- ^ See Olitzky and Raphael (1996), p. 56 and Pine (2010).

- ^ See Olitzky and Raphael (1996), p. 56 and Rosenbaum (1976), p. 120.

- ^ Ross and Schechner (2007), p. 292.

- ^ Ross (2003), p. 37.

- ^ Ross and Schechner (2007), p. 293.

- ^ See Olitzky and Raphael (1996), p. 56 and History of Temple Sinai (1875–2009), Temple Israel website.

- ^ Pine (2010).

- ^ Fernandez, Lisa. "Oakland couple, both 95, die within 3 days of each other after 70-year marriage". KTVU. KTVU. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- ^ See Tracey (2007), Roth (2001), Isaac (2009), p. 92, Temple History, Temple Beth Israel (Jackson, Michigan) website and Clergy, Temple Sinai website.

- ^ See Isaac (2009), p. 105 and Board of Directors, July 1, 2007, to June 30, 2008, JFCS of East Bay website.

- ^ Cohn (2003).

- ^ Olson (2009).

- ^ dan pine. "New lecture series in Oakland hopes to generate a better acceptance of Jews of color". jweekly.com.

- ^ "China, Israel and Judaism". shma.com.

- ^ "Shorts", j., September 1, 2005.

- ^ Altman-Ohr (2009).

- ^ Palmer (2008), p. 9.

- ^ According to History of Temple Sinai (1875–2009), Temple Israel website. According to Isaac (2009), p. 123, the groundbreaking took place in October 2008.

- ^ See Pine (2008), Palmer (2008), p. 9 and Isaac (2009), p. 123.

- ^ Letter from Rabbinic Search Co-chairs, December 2008.

- ^ Letter from Rabbi Chester to the congregation, December 18, 2008.

- ^ "Introducing Rabbi Andrew Straus". April 3, 2014. Retrieved February 27, 2021.

- ^ See Isaac (2009), p. 92, Bibel (2009) and History of Temple Sinai (1875–2011), Temple Israel website.

- ^ Fishkoff, Sue (September 21, 2017). "Anti-Semitic graffiti defaces Oakland Temple Sinai on Rosh Hashanah – J". Jweekly.com. Retrieved September 27, 2017.

References

[edit]- History of Temple Sinai (1875–2011), Temple Sinai website, Who We Are, History & Bylaws. Accessed January 2, 2012.

- Clergy, Temple Sinai website, Who We Are, Staff. Accessed January 2, 2012.

- Im Tirtzu: If you will it, it is no dream. Synagogue website, Who We Are, Capital Campaign/Expansion Project. Accessed March 27, 2010.

- "By-Laws of the First Hebrew Congregation of Oakland" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 27, 2011. (77.0 KB), First Hebrew Congregation of Oakland, October 2006.

- "From Lynn Simon and Wayne Batavia, Co-chairs of the Rabbinic Search Committee" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 27, 2011. (42.5 KB), Temple Sinai website, Rabbinic Search. Accessed March 27, 2010.

- "Letter from Rabbi Chester to the congregation" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 27, 2011. (15.1 KB), Temple Sinai website, December 18, 2008. Accessed March 27, 2010.

- American Jewish Committee. "Special Articles" (PDF). (1.27 MB), American Jewish Year Book, Jewish Publication Society, Volume 5 (1903–1904).

- American Jewish Committee. "Directories" (PDF). (7.72 MB), American Jewish Year Book, Jewish Publication Society, Volume 9 (1907–1908).

- American Jewish Committee. "Directories" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 13, 2010. Retrieved June 9, 2010. (6.06 MB), American Jewish Year Book, Jewish Publication Society, Volume 21 (1919–1920).

- American Jewish Committee. "Directories" (PDF). (1.62 MB), American Jewish Year Book, Jewish Publication Society, Volume 73 (1972).

- Board of Directors, July 1, 2007, to June 30, 2008, Jewish Family and Child Services of the East Bay website. Archived on the Internet Archive. Accessed March 27, 2010.

- Board of Directors, July 1, 2009, to June 30, 2010, Jewish Family and Child Services of the East Bay website. Accessed March 27, 2010.

- Altman-Ohr, Andy. "Grandeur takes center stage for High Holy Days", J. The Jewish News of Northern California, September 10, 2009.

- Bibel, Barbara M. Jews of Oakland and Berkeley, Association of Jewish Libraries Newsletter, December 1, 2009.

- Cohn, Abby."Ex-TV documentarian shifts focus, takes Sinai bimah", J. The Jewish News of Northern California, August 22, 2003.

- Conmy, Peter Thomas. The Beginnings of Oakland, California, A.U.C., Oakland Public Library, 1961.

- Isaac, Frederick. Jews of Oakland and Berkeley, Arcadia Publishing, 2009. ISBN 978-0-7385-7033-4

- Kahn, Ava Fran. Jewish Voices of the California Gold Rush: A Documentary History, 1849–1880, Wayne State University Press, 2002. ISBN 978-0-8143-2859-0

- Kline, Wendy. Building a Better Race: Gender, Sexuality, and Eugenics from the Turn of the Century to the Baby Boom, University of California Press, 2005. ISBN 978-0-520-24674-4

- Lachoff, Irwin; Kahn, Catherine C. The Jewish Community of New Orleans, Arcadia Publishing, 2005. ISBN 978-0-7385-1835-0

- Landman, Isaac. The Universal Jewish Encyclopedia, Volume 8, Universal Jewish Encyclopedia Co. Inc., 1942.

- Landman, Isaac. The Universal Jewish Encyclopedia, Volume 9, Universal Jewish Encyclopedia Co. Inc., 1943.

- No byline. "Shorts: Bay Area", J. The Jewish News of Northern California, September 1, 2005.

- Olitzky, Kerry M.; Raphael, Marc Lee. The American Synagogue: A Historical Dictionary and Sourcebook, Greenwood Press, 1996. ISBN 978-0-313-28856-2

- Olson, David. "Riverside rabbi took nontraditional path", The Press–Enterprise, October 16, 2009.

- Palmer, Cora. "Evaluation of Proposed Project Affecting Temple Sinai, Oakland" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 27, 2011. (6.31 MB), Page and Turnbull, March 10, 2008.

- Pine, Dan. "It's back to school for Temple Sinai: Oakland congregation moving to Merritt College during construction", J. The Jewish News of Northern California, August 29, 2008.

- Pine, Dan. "At 85, well-known rabbi returns to the bimah ... with a one-man show that includes singing", J. The Jewish News of Northern California, January 14, 2010

- Raphael, Marc Lee. The Columbia History of Jews and Judaism in America, Columbia University Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0-231-13222-0

- Reidel, James. Vanished Act: The Life and Art of Weldon Kees, University of Nebraska Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0-8032-5977-5

- Rosenbaum, Fred. Free to Choose: The Making of a Jewish Community in the American West, Judah L. Magnes Museum, 1976.

- Rosenbaum, Fred, "San Francisco-Oakland: The Native Son", in Brinner, William M.; Rischin, Moses. Like All the Nations?: The Life and Legacy of Judah L. Magnes, State University of New York Press, 1987. ISBN 978-0-88706-507-1

- Rosenbaum, Fred. Visions of Reform: Congregation Emanu-El and the Jews of San Francisco, 1849–1999, Judah L. Magnes Museum, 2000. ISBN 978-0-943376-69-1

- Rosenbaum, Fred. Cosmopolitans: A Social and Cultural History of the Jews of the San Francisco Bay Area, University of California Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0-520-25913-3

- Ross, Janice, "Anna Halprin and the 1960s: Acting in the Gap between the Personal, the Public, and the Political", in Banes, Sally; Baryshnikov, Mikhail; Harris, Andrea. Reinventing Dance in the 1960s: Everything was Possible, University of Wisconsin Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0-299-18014-0

- Ross, Janice; Schechner, Richard. Anna Halprin: Experience as Dance, University of California Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0-520-24757-4

- Roth, Arnold. "Stockton's Jewish Community and Temple Israel", History, Temple Israel (Stockton, California) website, December 17, 2001. Accessed March 27, 2010.

- Taylor, Marion Ann; Weir, Heather E. Let Her Speak for Herself: Nineteenth-century Women Writing on Women in Genesis, Baylor University Press, 2006. ISBN 978-1-932792-53-9

- Temple History, Temple Beth Israel (Jackson, Michigan) website. Accessed March 27, 2010.

- Tracey, Julia Park. "Man with a Mission", The Monthly, December 2007.

- Voorsanger, A.W. "Western Jewry: An Account of the Achievements of the Jews and Judaism in California Including Eulogies and Biographies", Emanu-El, California Press, 1916.

- Wachs, Sharona R. American Jewish Liturgies: A Bibliography of American Jewish Liturgy from the Establishment of the Press in the Colonies Through 1925, Volume 14 of Bibliographica Judaica, Hebrew Union College Press, 1997. ISBN 978-0-87820-912-5

- Weissbach, Lee Shai. "Community and subcommunity in small-town America, 1880–1950", Jewish History, Springer Netherlands, Volume 15, Number 2 / May, 2001.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Eskenazi, Joe (August 4, 2005). "That's the ticket: Sinai, Oakland reach parking compromise". J. The Jewish News of Northern California.

- 1875 establishments in California

- 20th-century synagogues in the United States

- Beaux-Arts architecture in California

- Beaux-Arts synagogues

- Classical Reform Judaism

- Culture of Oakland, California

- Jewish organizations established in 1875

- Oakland Designated Landmarks

- Polish-Jewish culture in the United States

- Reform synagogues in California

- Synagogue buildings with domes

- Synagogues completed in 1878

- Synagogues completed in 1886

- Synagogues completed in 1896

- Synagogues completed in 1914

- Synagogues in Oakland, California

- Synagogues in California