Template:Excerpt/testcases2

| This is the template test cases page for the sandbox of Template:Excerpt. to update the examples. If there are many examples of a complicated template, later ones may break due to limits in MediaWiki; see the HTML comment "NewPP limit report" in the rendered page. You can also use Special:ExpandTemplates to examine the results of template uses. You can test how this page looks in the different skins and parsers with these links: |

Lists

[edit]| {{Excerpt}} | {{Excerpt/sandbox}} |

|---|---|

|

|

|

Paragraphs

[edit]| {{Excerpt}} | {{Excerpt/sandbox}} | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Science is a systematic discipline that builds and organises knowledge in the form of testable hypotheses and predictions about the universe.[1][2] Modern science is typically divided into two or three major branches:[3] the natural sciences (e.g., physics, chemistry, and biology), which study the physical world; and the behavioural sciences (e.g., economics, psychology, and sociology), which study individuals and societies.[4][5] The formal sciences (e.g., logic, mathematics, and theoretical computer science), which study formal systems governed by axioms and rules,[6][7] are sometimes described as being sciences as well; however, they are often regarded as a separate field because they rely on deductive reasoning instead of the scientific method or empirical evidence as their main methodology.[8][9] Applied sciences are disciplines that use scientific knowledge for practical purposes, such as engineering and medicine.[10][11][12] |

Science is a systematic discipline that builds and organises knowledge in the form of testable hypotheses and predictions about the universe.[1][2] Modern science is typically divided into two or three major branches:[3] the natural sciences (e.g., physics, chemistry, and biology), which study the physical world; and the behavioural sciences (e.g., economics, psychology, and sociology), which study individuals and societies.[4][5] The formal sciences (e.g., logic, mathematics, and theoretical computer science), which study formal systems governed by axioms and rules,[6][7] are sometimes described as being sciences as well; however, they are often regarded as a separate field because they rely on deductive reasoning instead of the scientific method or empirical evidence as their main methodology.[8][9] Applied sciences are disciplines that use scientific knowledge for practical purposes, such as engineering and medicine.[10][11][12] |

| {{Excerpt}} | {{Excerpt/sandbox}} | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

The history of science spans the majority of the historical record, with the earliest identifiable predecessors to modern science dating to the Bronze Age in Egypt and Mesopotamia (c. 3000–1200 BCE). Their contributions to mathematics, astronomy, and medicine entered and shaped the Greek natural philosophy of classical antiquity, whereby formal attempts were made to provide explanations of events in the physical world based on natural causes, while further advancements, including the introduction of the Hindu–Arabic numeral system, were made during the Golden Age of India.[1]: 12 [2][3][4] Scientific research deteriorated in these regions after the fall of the Western Roman Empire during the Early Middle Ages (400–1000 CE), but in the Medieval renaissances (Carolingian Renaissance, Ottonian Renaissance and the Renaissance of the 12th century) scholarship flourished again. Some Greek manuscripts lost in Western Europe were preserved and expanded upon in the Middle East during the Islamic Golden Age,[5] along with the later efforts of Byzantine Greek scholars who brought Greek manuscripts from the dying Byzantine Empire to Western Europe at the start of the Renaissance. |

The history of science spans the majority of the historical record, with the earliest identifiable predecessors to modern science dating to the Bronze Age in Egypt and Mesopotamia (c. 3000–1200 BCE). Their contributions to mathematics, astronomy, and medicine entered and shaped the Greek natural philosophy of classical antiquity, whereby formal attempts were made to provide explanations of events in the physical world based on natural causes, while further advancements, including the introduction of the Hindu–Arabic numeral system, were made during the Golden Age of India.[1]: 12 [2][3][4] Scientific research deteriorated in these regions after the fall of the Western Roman Empire during the Early Middle Ages (400–1000 CE), but in the Medieval renaissances (Carolingian Renaissance, Ottonian Renaissance and the Renaissance of the 12th century) scholarship flourished again. Some Greek manuscripts lost in Western Europe were preserved and expanded upon in the Middle East during the Islamic Golden Age,[5] along with the later efforts of Byzantine Greek scholars who brought Greek manuscripts from the dying Byzantine Empire to Western Europe at the start of the Renaissance. |

| {{Excerpt}} | {{Excerpt/sandbox}} | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Science is a systematic discipline that builds and organises knowledge in the form of testable hypotheses and predictions about the universe.[1][2] Modern science is typically divided into two or three major branches:[3] the natural sciences (e.g., physics, chemistry, and biology), which study the physical world; and the behavioural sciences (e.g., economics, psychology, and sociology), which study individuals and societies.[4][5] The formal sciences (e.g., logic, mathematics, and theoretical computer science), which study formal systems governed by axioms and rules,[6][7] are sometimes described as being sciences as well; however, they are often regarded as a separate field because they rely on deductive reasoning instead of the scientific method or empirical evidence as their main methodology.[8][9] Applied sciences are disciplines that use scientific knowledge for practical purposes, such as engineering and medicine.[10][11][12] The history of science spans the majority of the historical record, with the earliest identifiable predecessors to modern science dating to the Bronze Age in Egypt and Mesopotamia (c. 3000–1200 BCE). Their contributions to mathematics, astronomy, and medicine entered and shaped the Greek natural philosophy of classical antiquity, whereby formal attempts were made to provide explanations of events in the physical world based on natural causes, while further advancements, including the introduction of the Hindu–Arabic numeral system, were made during the Golden Age of India.[13]: 12 [14][15][16] Scientific research deteriorated in these regions after the fall of the Western Roman Empire during the Early Middle Ages (400–1000 CE), but in the Medieval renaissances (Carolingian Renaissance, Ottonian Renaissance and the Renaissance of the 12th century) scholarship flourished again. Some Greek manuscripts lost in Western Europe were preserved and expanded upon in the Middle East during the Islamic Golden Age,[17] along with the later efforts of Byzantine Greek scholars who brought Greek manuscripts from the dying Byzantine Empire to Western Europe at the start of the Renaissance. The recovery and assimilation of Greek works and Islamic inquiries into Western Europe from the 10th to 13th centuries revived natural philosophy,[18][19][20] which was later transformed by the Scientific Revolution that began in the 16th century[21] as new ideas and discoveries departed from previous Greek conceptions and traditions.[22][23] The scientific method soon played a greater role in knowledge creation and it was not until the 19th century that many of the institutional and professional features of science began to take shape,[24][25] along with the changing of "natural philosophy" to "natural science".[26] |

Science is a systematic discipline that builds and organises knowledge in the form of testable hypotheses and predictions about the universe.[1][2] Modern science is typically divided into two or three major branches:[3] the natural sciences (e.g., physics, chemistry, and biology), which study the physical world; and the behavioural sciences (e.g., economics, psychology, and sociology), which study individuals and societies.[4][5] The formal sciences (e.g., logic, mathematics, and theoretical computer science), which study formal systems governed by axioms and rules,[6][7] are sometimes described as being sciences as well; however, they are often regarded as a separate field because they rely on deductive reasoning instead of the scientific method or empirical evidence as their main methodology.[8][9] Applied sciences are disciplines that use scientific knowledge for practical purposes, such as engineering and medicine.[10][11][12] The history of science spans the majority of the historical record, with the earliest identifiable predecessors to modern science dating to the Bronze Age in Egypt and Mesopotamia (c. 3000–1200 BCE). Their contributions to mathematics, astronomy, and medicine entered and shaped the Greek natural philosophy of classical antiquity, whereby formal attempts were made to provide explanations of events in the physical world based on natural causes, while further advancements, including the introduction of the Hindu–Arabic numeral system, were made during the Golden Age of India.[13]: 12 [14][15][16] Scientific research deteriorated in these regions after the fall of the Western Roman Empire during the Early Middle Ages (400–1000 CE), but in the Medieval renaissances (Carolingian Renaissance, Ottonian Renaissance and the Renaissance of the 12th century) scholarship flourished again. Some Greek manuscripts lost in Western Europe were preserved and expanded upon in the Middle East during the Islamic Golden Age,[17] along with the later efforts of Byzantine Greek scholars who brought Greek manuscripts from the dying Byzantine Empire to Western Europe at the start of the Renaissance. The recovery and assimilation of Greek works and Islamic inquiries into Western Europe from the 10th to 13th centuries revived natural philosophy,[18][19][20] which was later transformed by the Scientific Revolution that began in the 16th century[21] as new ideas and discoveries departed from previous Greek conceptions and traditions.[22][23] The scientific method soon played a greater role in knowledge creation and it was not until the 19th century that many of the institutional and professional features of science began to take shape,[24][25] along with the changing of "natural philosophy" to "natural science".[26] |

| {{Excerpt}} | {{Excerpt/sandbox}} |

|---|---|

|

Science is a systematic discipline that builds and organises knowledge in the form of testable hypotheses and predictions about the universe.[1][2] Modern science is typically divided into two or three major branches:[3] the natural sciences (e.g., physics, chemistry, and biology), which study the physical world; and the behavioural sciences (e.g., economics, psychology, and sociology), which study individuals and societies.[4][5] The formal sciences (e.g., logic, mathematics, and theoretical computer science), which study formal systems governed by axioms and rules,[6][7] are sometimes described as being sciences as well; however, they are often regarded as a separate field because they rely on deductive reasoning instead of the scientific method or empirical evidence as their main methodology.[8][9] Applied sciences are disciplines that use scientific knowledge for practical purposes, such as engineering and medicine.[10][11][12] The history of science spans the majority of the historical record, with the earliest identifiable predecessors to modern science dating to the Bronze Age in Egypt and Mesopotamia (c. 3000–1200 BCE). Their contributions to mathematics, astronomy, and medicine entered and shaped the Greek natural philosophy of classical antiquity, whereby formal attempts were made to provide explanations of events in the physical world based on natural causes, while further advancements, including the introduction of the Hindu–Arabic numeral system, were made during the Golden Age of India.[13]: 12 [14][15][16] Scientific research deteriorated in these regions after the fall of the Western Roman Empire during the Early Middle Ages (400–1000 CE), but in the Medieval renaissances (Carolingian Renaissance, Ottonian Renaissance and the Renaissance of the 12th century) scholarship flourished again. Some Greek manuscripts lost in Western Europe were preserved and expanded upon in the Middle East during the Islamic Golden Age,[17] along with the later efforts of Byzantine Greek scholars who brought Greek manuscripts from the dying Byzantine Empire to Western Europe at the start of the Renaissance. The recovery and assimilation of Greek works and Islamic inquiries into Western Europe from the 10th to 13th centuries revived natural philosophy,[18][19][20] which was later transformed by the Scientific Revolution that began in the 16th century[21] as new ideas and discoveries departed from previous Greek conceptions and traditions.[22][23] The scientific method soon played a greater role in knowledge creation and it was not until the 19th century that many of the institutional and professional features of science began to take shape,[24][25] along with the changing of "natural philosophy" to "natural science".[26] New knowledge in science is advanced by research from scientists who are motivated by curiosity about the world and a desire to solve problems.[27][28] Contemporary scientific research is highly collaborative and is usually done by teams in academic and research institutions,[29] government agencies,[30] and companies.[31] The practical impact of their work has led to the emergence of science policies that seek to influence the scientific enterprise by prioritising the ethical and moral development of commercial products, armaments, health care, public infrastructure, and environmental protection. |

Science is a systematic discipline that builds and organises knowledge in the form of testable hypotheses and predictions about the universe.[1][2] Modern science is typically divided into two or three major branches:[3] the natural sciences (e.g., physics, chemistry, and biology), which study the physical world; and the behavioural sciences (e.g., economics, psychology, and sociology), which study individuals and societies.[4][5] The formal sciences (e.g., logic, mathematics, and theoretical computer science), which study formal systems governed by axioms and rules,[6][7] are sometimes described as being sciences as well; however, they are often regarded as a separate field because they rely on deductive reasoning instead of the scientific method or empirical evidence as their main methodology.[8][9] Applied sciences are disciplines that use scientific knowledge for practical purposes, such as engineering and medicine.[10][11][12] The history of science spans the majority of the historical record, with the earliest identifiable predecessors to modern science dating to the Bronze Age in Egypt and Mesopotamia (c. 3000–1200 BCE). Their contributions to mathematics, astronomy, and medicine entered and shaped the Greek natural philosophy of classical antiquity, whereby formal attempts were made to provide explanations of events in the physical world based on natural causes, while further advancements, including the introduction of the Hindu–Arabic numeral system, were made during the Golden Age of India.[13]: 12 [14][15][16] Scientific research deteriorated in these regions after the fall of the Western Roman Empire during the Early Middle Ages (400–1000 CE), but in the Medieval renaissances (Carolingian Renaissance, Ottonian Renaissance and the Renaissance of the 12th century) scholarship flourished again. Some Greek manuscripts lost in Western Europe were preserved and expanded upon in the Middle East during the Islamic Golden Age,[17] along with the later efforts of Byzantine Greek scholars who brought Greek manuscripts from the dying Byzantine Empire to Western Europe at the start of the Renaissance. The recovery and assimilation of Greek works and Islamic inquiries into Western Europe from the 10th to 13th centuries revived natural philosophy,[18][19][20] which was later transformed by the Scientific Revolution that began in the 16th century[21] as new ideas and discoveries departed from previous Greek conceptions and traditions.[22][23] The scientific method soon played a greater role in knowledge creation and it was not until the 19th century that many of the institutional and professional features of science began to take shape,[24][25] along with the changing of "natural philosophy" to "natural science".[26] New knowledge in science is advanced by research from scientists who are motivated by curiosity about the world and a desire to solve problems.[27][28] Contemporary scientific research is highly collaborative and is usually done by teams in academic and research institutions,[29] government agencies,[30] and companies.[31] The practical impact of their work has led to the emergence of science policies that seek to influence the scientific enterprise by prioritising the ethical and moral development of commercial products, armaments, health care, public infrastructure, and environmental protection. |

| {{Excerpt}} | {{Excerpt/sandbox}} |

|---|---|

| Science is a systematic discipline that builds and organises knowledge in the form of testable hypotheses and predictions about the universe.[1][2] Modern science is typically divided into two or three major branches:[3] the natural sciences (e.g., physics, chemistry, and biology), which study the physical world; and the behavioural sciences (e.g., economics, psychology, and sociology), which study individuals and societies.[4][5] The formal sciences (e.g., logic, mathematics, and theoretical computer science), which study formal systems governed by axioms and rules,[6][7] are sometimes described as being sciences as well; however, they are often regarded as a separate field because they rely on deductive reasoning instead of the scientific method or empirical evidence as their main methodology.[8][9] Applied sciences are disciplines that use scientific knowledge for practical purposes, such as engineering and medicine.[10][11][12] | Science is a systematic discipline that builds and organises knowledge in the form of testable hypotheses and predictions about the universe.[1][2] Modern science is typically divided into two or three major branches:[3] the natural sciences (e.g., physics, chemistry, and biology), which study the physical world; and the behavioural sciences (e.g., economics, psychology, and sociology), which study individuals and societies.[4][5] The formal sciences (e.g., logic, mathematics, and theoretical computer science), which study formal systems governed by axioms and rules,[6][7] are sometimes described as being sciences as well; however, they are often regarded as a separate field because they rely on deductive reasoning instead of the scientific method or empirical evidence as their main methodology.[8][9] Applied sciences are disciplines that use scientific knowledge for practical purposes, such as engineering and medicine.[10][11][12] |

Infoboxes

[edit]| {{Excerpt}} | {{Excerpt/sandbox}} |

|---|---|

Aristotle[A] (Attic Greek: Ἀριστοτέλης, romanized: Aristotélēs;[B] 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, and the arts. As the founder of the Peripatetic school of philosophy in the Lyceum in Athens, he began the wider Aristotelian tradition that followed, which set the groundwork for the development of modern science. Little is known about Aristotle's life. He was born in the city of Stagira in northern Greece during the Classical period. His father, Nicomachus, died when Aristotle was a child, and he was brought up by a guardian. At around eighteen years old, he joined Plato's Academy in Athens and remained there until the age of thirty seven (c. 347 BC). Shortly after Plato died, Aristotle left Athens and, at the request of Philip II of Macedon, tutored his son Alexander the Great beginning in 343 BC. He established a library in the Lyceum, which helped him to produce many of his hundreds of books on papyrus scrolls. Though Aristotle wrote many treatises and dialogues for publication, only around a third of his original output has survived, none of it intended for publication. Aristotle provided a complex synthesis of the various philosophies existing prior to him. His teachings and methods of inquiry have had a significant impact across the world, and remain a subject of contemporary philosophical discussion. Aristotle's views profoundly shaped medieval scholarship. The influence of his physical science extended from late antiquity and the Early Middle Ages into the Renaissance, and was not replaced systematically until the Enlightenment and theories such as classical mechanics were developed. He influenced Judeo-Islamic philosophies during the Middle Ages, as well as Christian theology, especially the Neoplatonism of the Early Church and the scholastic tradition of the Catholic Church. Aristotle was revered among medieval Muslim scholars as "The First Teacher", and among medieval Christians like Thomas Aquinas as simply "The Philosopher", while the poet Dante called him "the master of those who know". He has been referred to as the first scientist. His works contain the earliest known formal study of logic, and were studied by medieval scholars such as Peter Abelard and Jean Buridan. His influence on logic continued well into the 19th century. In addition, his ethics, although always influential, gained renewed interest with the modern advent of virtue ethics. |

Aristotle[C] (Attic Greek: Ἀριστοτέλης, romanized: Aristotélēs;[D] 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, and the arts. As the founder of the Peripatetic school of philosophy in the Lyceum in Athens, he began the wider Aristotelian tradition that followed, which set the groundwork for the development of modern science. Little is known about Aristotle's life. He was born in the city of Stagira in northern Greece during the Classical period. His father, Nicomachus, died when Aristotle was a child, and he was brought up by a guardian. At around eighteen years old, he joined Plato's Academy in Athens and remained there until the age of thirty seven (c. 347 BC). Shortly after Plato died, Aristotle left Athens and, at the request of Philip II of Macedon, tutored his son Alexander the Great beginning in 343 BC. He established a library in the Lyceum, which helped him to produce many of his hundreds of books on papyrus scrolls. Though Aristotle wrote many treatises and dialogues for publication, only around a third of his original output has survived, none of it intended for publication. Aristotle provided a complex synthesis of the various philosophies existing prior to him. His teachings and methods of inquiry have had a significant impact across the world, and remain a subject of contemporary philosophical discussion. Aristotle's views profoundly shaped medieval scholarship. The influence of his physical science extended from late antiquity and the Early Middle Ages into the Renaissance, and was not replaced systematically until the Enlightenment and theories such as classical mechanics were developed. He influenced Judeo-Islamic philosophies during the Middle Ages, as well as Christian theology, especially the Neoplatonism of the Early Church and the scholastic tradition of the Catholic Church. Aristotle was revered among medieval Muslim scholars as "The First Teacher", and among medieval Christians like Thomas Aquinas as simply "The Philosopher", while the poet Dante called him "the master of those who know". He has been referred to as the first scientist. His works contain the earliest known formal study of logic, and were studied by medieval scholars such as Peter Abelard and Jean Buridan. His influence on logic continued well into the 19th century. In addition, his ethics, although always influential, gained renewed interest with the modern advent of virtue ethics. |

| {{Excerpt}} | {{Excerpt/sandbox}} |

|---|---|

|

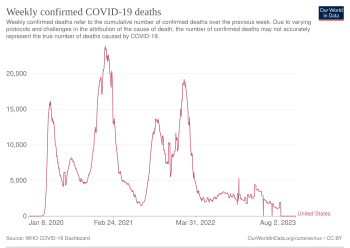

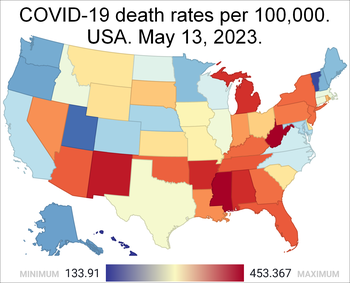

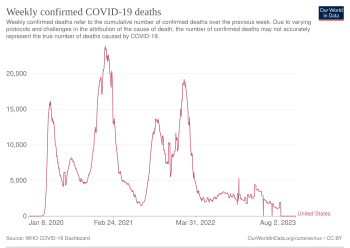

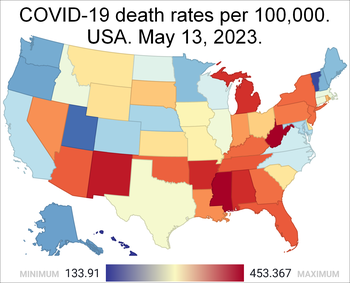

On December 31, 2019, China announced the discovery of a cluster of pneumonia cases in Wuhan. The first American case was reported on January 20,[2] and Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar declared a public health emergency on January 31.[3] Restrictions were placed on flights arriving from China,[4][5] but the initial U.S. response to the pandemic was otherwise slow in terms of preparing the healthcare system, stopping other travel, and testing.[6][7][8][a][10] The first known American deaths occurred in February[11] and in late February President Donald Trump proposed allocating $2.5 billion to fight the outbreak. Instead, Congress approved $8.3 billion with only Senator Rand Paul and two House representatives (Andy Biggs and Ken Buck) voting against, and Trump signed the bill, the Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2020, on March 6.[12] Trump declared a national emergency on March 13.[13] The government also purchased large quantities of medical equipment, invoking the Defense Production Act of 1950 to assist.[14] By mid-April, disaster declarations were made by all states and territories as they all had increasing cases. A second wave of infections began in June, following relaxed restrictions in several states, leading to daily cases surpassing 60,000. By mid-October, a third surge of cases began; there were over 200,000 new daily cases during parts of December 2020 and January 2021.[15][16] COVID-19 vaccines became available in December 2020, under emergency use, beginning the national vaccination program, with the first vaccine officially approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on August 23, 2021.[17] Studies have shown them to be highly protective against severe illness, hospitalization, and death. In comparison with fully vaccinated people, the CDC found that those who were unvaccinated were from 5 to nearly 30 times more likely to become either infected or hospitalized. There has nonetheless been some vaccine hesitancy for various reasons, although side effects are rare.[18][19] There were also numerous reports that unvaccinated COVID-19 patients strained the capacity of hospitals throughout the country, forcing many to turn away patients with life-threatening diseases. A fourth rise in infections began in March 2021 amidst the rise of the Alpha variant, a more easily transmissible variant first detected in the United Kingdom. That was followed by a rise of the Delta variant, an even more infectious mutation first detected in India, leading to increased efforts to ensure safety. The January 2022 emergence of the Omicron variant, which was first discovered in South Africa, led to record highs in hospitalizations and cases in early 2022, with as many as 1.5 million new infections reported in a single day.[20] By the end of 2022, an estimated 77.5% of Americans had had COVID-19 at least once, according to the CDC.[21] State and local responses to the pandemic during the public health emergency included the requirement to wear a face mask in specified situations (mask mandates), prohibition and cancellation of large-scale gatherings (including festivals and sporting events), stay-at-home orders, and school closures.[22] Disproportionate numbers of cases were observed among Black and Latino populations,[23][24][25] as well as elevated levels of vaccine hesitancy,[26][27] and there was a sharp increase in reported incidents of xenophobia and racism against Asian Americans.[28][29] Clusters of infections and deaths occurred in many areas.[b] The COVID-19 pandemic also saw the emergence of misinformation and conspiracy theories,[32] and highlighted weaknesses in the U.S. public health system.[10][33][34] In the United States, there have been 103,436,829[35] confirmed cases of COVID-19 with 1,209,009[35] confirmed deaths, the most of any country, and the 17th highest per capita worldwide.[36] The COVID-19 pandemic ranks as the deadliest disaster in the country's history.[37] It was the third-leading cause of death in the U.S. in 2020, behind heart disease and cancer.[38] From 2019 to 2020, U.S. life expectancy dropped by three years for Hispanic and Latino Americans, 2.9 years for African Americans, and 1.2 years for white Americans.[39] In 2021, U.S. deaths due to COVID-19 rose,[40] and life expectancy fell.[41] |

On December 31, 2019, China announced the discovery of a cluster of pneumonia cases in Wuhan. The first American case was reported on January 20,[2] and Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar declared a public health emergency on January 31.[3] Restrictions were placed on flights arriving from China,[4][5] but the initial U.S. response to the pandemic was otherwise slow in terms of preparing the healthcare system, stopping other travel, and testing.[6][7][8][c][10] The first known American deaths occurred in February[11] and in late February President Donald Trump proposed allocating $2.5 billion to fight the outbreak. Instead, Congress approved $8.3 billion with only Senator Rand Paul and two House representatives (Andy Biggs and Ken Buck) voting against, and Trump signed the bill, the Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2020, on March 6.[12] Trump declared a national emergency on March 13.[13] The government also purchased large quantities of medical equipment, invoking the Defense Production Act of 1950 to assist.[14] By mid-April, disaster declarations were made by all states and territories as they all had increasing cases. A second wave of infections began in June, following relaxed restrictions in several states, leading to daily cases surpassing 60,000. By mid-October, a third surge of cases began; there were over 200,000 new daily cases during parts of December 2020 and January 2021.[15][16] COVID-19 vaccines became available in December 2020, under emergency use, beginning the national vaccination program, with the first vaccine officially approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on August 23, 2021.[17] Studies have shown them to be highly protective against severe illness, hospitalization, and death. In comparison with fully vaccinated people, the CDC found that those who were unvaccinated were from 5 to nearly 30 times more likely to become either infected or hospitalized. There has nonetheless been some vaccine hesitancy for various reasons, although side effects are rare.[18][19] There were also numerous reports that unvaccinated COVID-19 patients strained the capacity of hospitals throughout the country, forcing many to turn away patients with life-threatening diseases. A fourth rise in infections began in March 2021 amidst the rise of the Alpha variant, a more easily transmissible variant first detected in the United Kingdom. That was followed by a rise of the Delta variant, an even more infectious mutation first detected in India, leading to increased efforts to ensure safety. The January 2022 emergence of the Omicron variant, which was first discovered in South Africa, led to record highs in hospitalizations and cases in early 2022, with as many as 1.5 million new infections reported in a single day.[20] By the end of 2022, an estimated 77.5% of Americans had had COVID-19 at least once, according to the CDC.[21] State and local responses to the pandemic during the public health emergency included the requirement to wear a face mask in specified situations (mask mandates), prohibition and cancellation of large-scale gatherings (including festivals and sporting events), stay-at-home orders, and school closures.[22] Disproportionate numbers of cases were observed among Black and Latino populations,[23][24][25] as well as elevated levels of vaccine hesitancy,[26][27] and there was a sharp increase in reported incidents of xenophobia and racism against Asian Americans.[28][29] Clusters of infections and deaths occurred in many areas.[d] The COVID-19 pandemic also saw the emergence of misinformation and conspiracy theories,[32] and highlighted weaknesses in the U.S. public health system.[10][33][34] In the United States, there have been 103,436,829[35] confirmed cases of COVID-19 with 1,209,009[35] confirmed deaths, the most of any country, and the 17th highest per capita worldwide.[36] The COVID-19 pandemic ranks as the deadliest disaster in the country's history.[37] It was the third-leading cause of death in the U.S. in 2020, behind heart disease and cancer.[38] From 2019 to 2020, U.S. life expectancy dropped by three years for Hispanic and Latino Americans, 2.9 years for African Americans, and 1.2 years for white Americans.[39] In 2021, U.S. deaths due to COVID-19 rose,[40] and life expectancy fell.[41] |

| {{Excerpt}} | {{Excerpt/sandbox}} | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Map of Belgium and its provinces with the spread of COVID-19 as of 9 July 2020[1]

The COVID-19 pandemic in Belgium has resulted in 4,891,945[2] confirmed cases of COVID-19 and 34,339[2] deaths. The virus was confirmed to have spread to Belgium on 4 February 2020, when one of a group of nine Belgians repatriated from Wuhan to Brussels was reported to have tested positive for the coronavirus.[3][4] Transmission within Belgium was confirmed in early March; authorities linked this to holidaymakers returning from Northern Italy at the end of the half-term holidays.[5][6] The epidemic increased rapidly in March–April 2020. By the end of March all 10 provinces of the country had registered cases.[citation needed] By March 2021, Belgium had the third highest number of COVID-19 deaths per head of population in the world, according to data compiled by Johns Hopkins University. However, Belgium may have been over-reporting the number of cases, with health officials reporting that suspected cases were being reported along with confirmed cases.[7] Unlike some countries that publish figures based primarily on confirmed hospital deaths, the death figures reported by the Belgian authorities included deaths in the community, such as in care homes, confirmed to have been caused by the virus, as well as a much larger number of such deaths suspected to have been caused by the virus, even if the person was not tested.[8] |

Map of Belgium and its provinces with the spread of COVID-19 as of 9 July 2020[1]

The COVID-19 pandemic in Belgium has resulted in 4,891,945[2] confirmed cases of COVID-19 and 34,339[2] deaths. The virus was confirmed to have spread to Belgium on 4 February 2020, when one of a group of nine Belgians repatriated from Wuhan to Brussels was reported to have tested positive for the coronavirus.[3][4] Transmission within Belgium was confirmed in early March; authorities linked this to holidaymakers returning from Northern Italy at the end of the half-term holidays.[5][6] The epidemic increased rapidly in March–April 2020. By the end of March all 10 provinces of the country had registered cases.[citation needed] By March 2021, Belgium had the third highest number of COVID-19 deaths per head of population in the world, according to data compiled by Johns Hopkins University. However, Belgium may have been over-reporting the number of cases, with health officials reporting that suspected cases were being reported along with confirmed cases.[7] Unlike some countries that publish figures based primarily on confirmed hospital deaths, the death figures reported by the Belgian authorities included deaths in the community, such as in care homes, confirmed to have been caused by the virus, as well as a much larger number of such deaths suspected to have been caused by the virus, even if the person was not tested.[8] |

Quotes

[edit]| {{Excerpt}} | {{Excerpt/sandbox}} | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

text text texttext text text |

text text texttext text text | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| {{Excerpt}} | {{Excerpt/sandbox}} | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

text text texttext text text |

text text texttext text text | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| {{Excerpt}} | {{Excerpt/sandbox}} | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

text text texttext text text |

text text texttext text text | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| {{Excerpt}} | {{Excerpt/sandbox}} | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

text text text

Saurita nigripalpia is a species of moth in the subfamily Arctiinae. It was described by George Hampson in 1898. It is found in Mexico and Costa Rica.[1] |

text text text

Saurita nigripalpia is a species of moth in the subfamily Arctiinae. It was described by George Hampson in 1898. It is found in Mexico and Costa Rica.[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Templates

[edit]| {{Excerpt}} | {{Excerpt/sandbox}} | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

| {{Excerpt}} | {{Excerpt/sandbox}} | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Housing refers to the usage and possibly construction of shelter as living spaces, individually or collectively. Housing is a basic human need and a human right, playing a critical role in shaping the quality of life for individuals, families, and communities,[1] As such it is the main issue of housing organization and policy. |

Housing refers to the usage and possibly construction of shelter as living spaces, individually or collectively. Housing is a basic human need and a human right, playing a critical role in shaping the quality of life for individuals, families, and communities,[1] As such it is the main issue of housing organization and policy. |

Notes

[edit]- ^ A lack of mass testing obscured the extent of the outbreak.[9]

- ^ Examples of areas in which clusters occurred include urban areas, nursing homes, long-term care facilities, group homes for the intellectually disabled,[30] detention centers (including prisons), meatpacking plants, churches, and navy ships.[31]

- ^ A lack of mass testing obscured the extent of the outbreak.[9]

- ^ Examples of areas in which clusters occurred include urban areas, nursing homes, long-term care facilities, group homes for the intellectually disabled,[30] detention centers (including prisons), meatpacking plants, churches, and navy ships.[31]

- ^ /ˈærɪstɒtəl/ ARR-ih-stot-əl[1]

- ^ pronounced [aristotélɛːs]

- ^ /ˈærɪstɒtəl/ ARR-ih-stot-əl[1]

- ^ pronounced [aristotélɛːs]