Talk:History of the International Phonetic Alphabet

| This article is rated B-class on Wikipedia's content assessment scale. It is of interest to the following WikiProjects: | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Untitled

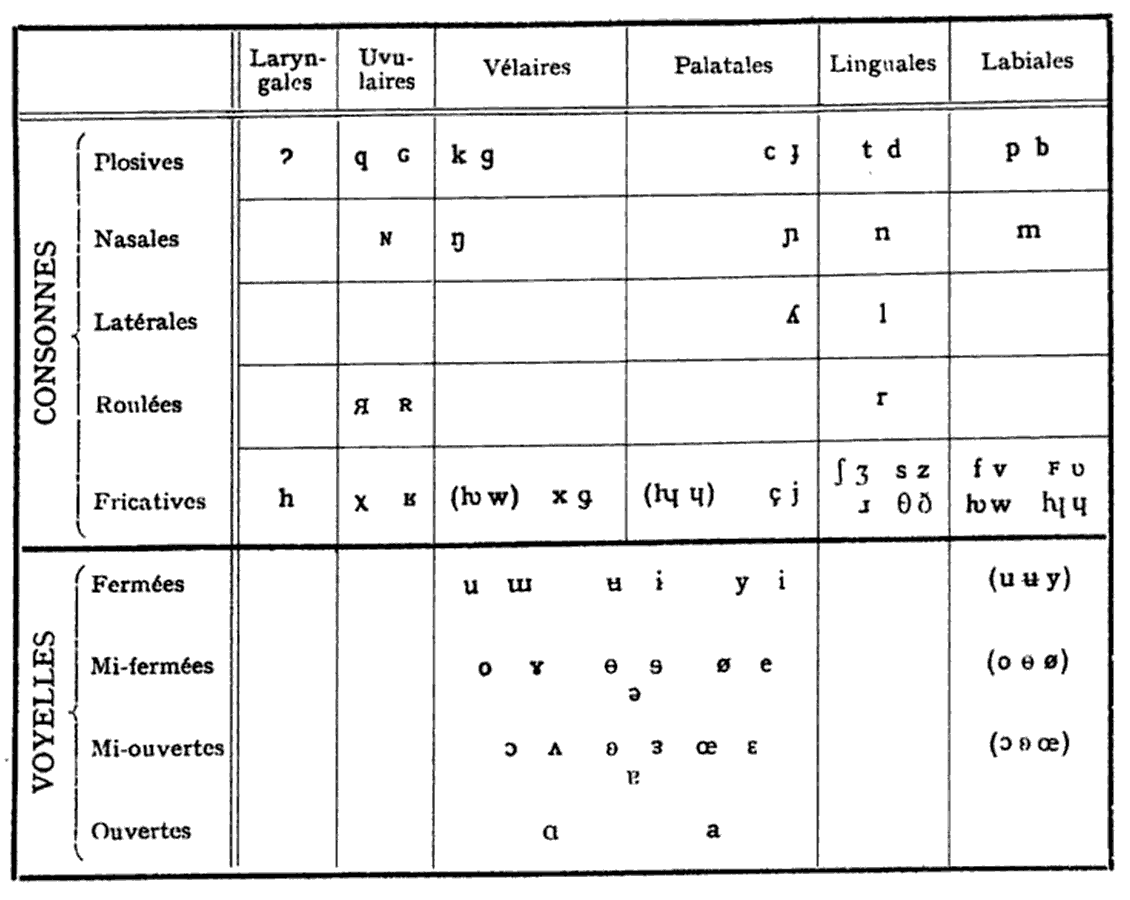

[edit]Why is the 1900 year table in French? - 81.15.146.91 22:34, 21 December 2005 (UTC)

- hi. that is the language it was published in. – ishwar (speak) 04:25, 22 December 2005 (UTC)

Dictionaries

[edit]I've written a bit about the history of IPA's use in dictionaries, at Pronunciation respelling for English, with a couple of online references. Might be useful for this article. Cheers. —Michael Z. 2006-08-17 08:01 Z

Near-close vowels

[edit]The charts uniformly give /ɪ, ʊ/ as the symbols for the near-close vowels. I'm pretty sure they were officially /ɩ, ɷ/ before 1989. This is confirmed also by Obsolete and nonstandard symbols in the IPA, so I'm changing it accordingly. User:Angr 19:00, 26 August 2006 (UTC)

- Yes, they were, I have a resource that shows the old forms in the 1949 version of the IPA. The ikiroid (talk·desk·Advise me) 20:00, 27 August 2006 (UTC)

Unrounded o

[edit]Another thing that's changed in the IPA is the symbol for the close-mid back unrounded vowel. The symbol used to be "baby gamma", with a flat top, which looked exactly like ɣ except without a descender. At some point (1989? 1993?) it was changed to "ram's horns", with a rounded top. The problem with showing this is that Unicode doesn't have separate characters for these: U+0264 LATIN SMALL LETTER RAMS HORN ɤ can, despite its name, be either "baby gamma" or "ram's horns" depending on the font. User:Angr 19:29, 26 August 2006 (UTC)

- Well, the article close-mid back unrounded vowel uses actual images to distinguish the two. We could do that, but it may be easier to just create a link to close-mid back unrounded vowel. The ikiroid (talk·desk·Advise me) 01:40, 16 September 2006 (UTC)

Aims and goals

[edit]Where did the "Formation of Aims and Goals" section come from? It seems to be uncited. Would it be reasonable to assume that it comes from the 1888 article by Paul Passy, cited in the bibliography? --Siva 00:32, 2 March 2007 (UTC)

- I haven't looked at that section yet, but I would bet either Principles or Handbook would cover it. --Kjoonlee 16:57, 6 September 2007 (UTC)

History unclear

[edit]Hi, I think it would be better to use a more chronological format, kind of like a changelog. The 1989 section mentions what changed with the 1993 version; this can be confusing, IMHO. --Kjoonlee 15:32, 17 May 2007 (UTC)

- I was thinking I would have to get Pullum's Phonetic Symbol Guide to polish up this article, but Handbook seems to cover a lot of the history (at least indirectly) in the appendices. I'll see what I can do... --Kjoonlee 16:56, 6 September 2007 (UTC)

Foundation of IPA: Places of articulation as alphabet

[edit]The ancient Tamil Grammar Tolkappiyam defines alphabet as the names of the places of articulation. Each place of articulation can produce a number of phonemes. The foundation for IPA is this principle of "Places of artiulation". One of the major functions of IPA is to identify, decribe and represent all of the possible phonemes under the title "Phonetic Alphabet". Sisrivas (talk) 11:42, 6 January 2008 (UTC)

First work to use apply IPA throughout

[edit]I would have thought that A Grammar of the Dialect of Windhill in 1893 by Joseph Wright would be a contender for this title? Does anyone know of other early linguistic works that made practical use of IPA? Epa101 (talk) 21:19, 16 April 2008 (UTC)

revisions of 1938, 1947 and 1951

[edit]Tsutomu Akamatsu, "A critique of the IPA chart (revised to 1951, 1979 and 1989)" has a copy of the 1951 revision. Should we fix the following sentence?

- The alphabet has undergone a number of revisions during its history, with the 1932 version used for over half a century, until the IPA Kiel Convention of 1989.

- And replace it with the following :

- The alphabet has undergone a number of revisions during its history, with the 1951 version used for almost thirty years, until the IPA Kiel Convention of 1989.

The differences with the 1932 revision are:

- ʓ and ʆ are in IPA-1951, not in IPA-1932

- ř (IPA-1932) is replaced by ɼ in IPA-1951

- ƞ and ɧ are in IPA-1951, not in IPA-1932

- already ɪ (small capital i) in IPA-1932

- ƾ and ƻ as alternatives to ts and dz are in IPA-1951, not in IPA-1932

- the r-coloured eɹ, aɹ, ɔɹ, ... and alternatives eʴ, aʴ, ɔʴ, ... and ᶒ, ᶏ, ᶗ, ... are in IPA-1951, not in IPA-1932

- the r-coloured əɹ, əʴ, ᶕ or ɚ are in IPA-1951, not in IPA-1932

- tongue raised e˔ or e̝ and tongue lowered e˕ or e̞ in IPA-1951, but only tongue slightly raised ˔ and tongue slightly lowered ˕ in IPA-1932

- tongue advanced u˖ or u̟, t˖ or t̟ and tongue retracted i˗ or i̠, t˗ or t̠ are in IPA-1951, not in IPA-1932

--Moyogo/ (talk) 19:07, 20 June 2012 (UTC)

- There's also revisions for 1938 and 1947 in Le Maître phonétique. I'll note the differences. --Moyogo/ (talk) 12:17, 21 June 2012 (UTC)

non IPA

[edit]I removed the illustration of Wulff 1888. There were many phonetic transcription systems back then, IPA borrowed from many. We are not going to illustrate all those here, at least not with full charts. --Moyogo/ (talk) 05:31, 20 July 2012 (UTC)

- It was an example, to clarify that the IPA was not created ex nihilo. We don't need to list them all just because we have one example. If you have a better example, great, but otherwise better this than nothing. — kwami (talk) 08:06, 20 July 2012 (UTC)

- It think including the full charts of Wulff is misleading, as it would be for the systems of Müller, Lepsius, Powell, Böhmer, Ascoli, Rousselot, or Lundell. Also is Wulff's system relevant? Did anybody use it? Did IPA actually borrow from it? An illustration from Sweet's Romic alphabet would be much more on point since IPA did borrow from it. --Moyogo/ (talk) 09:39, 20 July 2012 (UTC)

What about the 2015 revision?

[edit]

I think someone should add a few notes on the latest revision of 2015. Love —LiliCharlie (talk) 22:42, 18 March 2016 (UTC)

- What are the differences? — Sebastian 07:33, 11 April 2016 (UTC)

- There are hardly any, see the Association's page Full IPA Chart: "The 2015 chart makes minor changes to wording and layout, but otherwise reproduces the appearance of the 2005 chart. A few symbol substitutions have been made: [...]" As far as wording is concerned, the line of text underneath the pulmonic consonant table now reads "Symbols to the right in a cell are voiced, to the left are voiceless. [...]" instead of "Where symbols appear in pairs, the one to the right represents a voiced consonant. [...]" — Maybe the article should just mention that although a revised version was published in 2015 no symbols were added or withdrawn, but the appearance/glyphs of a few symbols has very slightly changed. Love —LiliCharlie (talk) 11:20, 11 April 2016 (UTC)

- I see; the text you quote is at https://www.internationalphoneticassociation.org/content/full-ipa-chart. I like your wording and will add it to the 2005 revision section. I will also rename that to 2005 revision and 2015 chart in analogy to the preceding section, with "chart", rather than "revision" or "update", being the name used at the full-ipa-chart. — Sebastian 15:35, 11 April 2016 (UTC)

Recent edit by Umimmak

[edit]This edit by Umimmak seems to contain several errors. The French is simply ungrammatical. The following might be the corrected versions:

- desizjɔ̃ dy kɔ̃sɛːj

desizjɔ̃ dyrəlativmɑ̃o prɔpozisjɔ̃ d la kɔ̃ferɑ̃ːs də *kɔpnag Décisions du conseil relativesmentaux propositions de la conférence de Copenhague - Il décide de remplacer les signes ꜰ, ʋ

withpar ɸ, β. Le signe ʋ sera désormais disponible pour représenterlela consonne labio-dentale non-fricative telle qu'elle existe dans certaines langues indiennes et en hollandais.

Can somebody please check? Love —LiliCharlie (talk) 11:25, 28 May 2017 (UTC)

- @LiliCharlie: Sorry, that's what I get for editing while sleepy :p. Thank you for catching those. The only thing that I think got over-corrected was that the original text definitely has "rəlativmɑ̃" [1], but all the other corrections make sense. Umimmak (talk) 11:47, 28 May 2017 (UTC)

Unusual symbols in Passy's 1921 chart

[edit]

In the chart from Paul Passy's 1921 L'Écriture phonétique internationale, 2nd ed., p. 6,[1] one encounters very peculiar symbols: an h-v ligature ⟨ƕ⟩ standing for what is now transcribed as [ʍ], and an h-ɥ ligature standing for [ɥ̊].[2] Adding ⟨h⟩ before a voiced consonant to denote voicelessness was apparently a common practice, so these seem like its logical extensions. Pullum & Ladusaw's Phonetic Symbol Guide (2nd ed., 1996) includes the former, saying "Recommended by Boas et al. (1916, 12) for a voiceless [w], following the use for Gothic" (p. 73), but doesn't mention an IPA or European usage, and doesn't include the latter ligature.

What is also interesting is that the set of vowel symbols on the chart is identical to the one in the 1993 chart, with the exception of ⟨ɒ ɪ ʏ ʊ æ ɶ⟩.[3] Pullum & Ladusaw only cite Abercrombie (1967: 161), Catford (1977: 178), Kurath (1939: 123), and Trager (1964: 22) as the earliest confirmed uses of ⟨ɘ ɜ ɞ⟩ (≠ ⟨ʚ⟩) in their current IPA values,[4] while we know ⟨ɵ⟩ as having the current value was already recognized as an alternative to [ö] as early as 1932 (see the article).[5] This means that the use of ⟨ɘ ɵ ɜ ʚ⟩ as their 1993 values dates back decades earlier than previously thought.[6]

How did these symbols wind up on the chart? Passy is the founder of the Association and L'Écriture was published by the Association, so they might as well be considered as having been part of the official IPA at one point, but none of them appear in the 1912 or 1932 chart. I wonder if they were ever mentioned in Le Maître Phonétique, apart from ⟨ɵ ʚ⟩ being suggested as alternatives to [ø œ].[7] And more important, what was Passy's rationale for including them?

When they revised the alphabet in 1993, did they know the IPA already had a history of publishing the symbols ⟨ɘ ɵ ɜ ʚ⟩ in their new definitions more than 70 years prior? Neither IPA (1993), a report on the revision, nor Catford (1990), the proposal upon which the revision of the vowels was based, mention this precedent. Esling (1995) cites again Abercrombie (1967) and Catford (1977) as the reason for the 1996 correction.[8] So it seems pretty unlikely they had the knowledge of ⟨ʚ⟩ having been used as open-mid central by an IPA publication 70 years prior. Had they known, I wonder if they would have still "corrected" it to ⟨ɞ⟩.

Does anyone have access to the book? If so I'd love to know if these symbols were mentioned elsewhere in the book. And, should they be so kind, I'd love to see it uploaded to Archive.org or wherever.[9] Nardog (talk) 15:01, 8 February 2018 (UTC)

References

- ^ Reprinted in Collins & Mees's 1998 Daniel Jones biography, The Real Professor Higgins: The Life and Career of Daniel Jones, p. 491.

- ^ The closest symbol I could find in Unicode to the latter ligature was ⟨խ⟩, but the final stroke isn't long enough.

- ^ Which is a bit weird considering ⟨ɪ ʏ ʊ æ⟩ comfortably predate 1921 and the non-cardinal [ɐ] is still included.

- ^ pp. 50, 55, 57. The earliest use of ⟨ʚ⟩ confirmed by Pullum & Ladusaw was Kurath (1939: 125), albeit as open-mid front, not central (p. 54).

- ^ According to the French Wikipedia, ⟨ɵ⟩ was approved in 1928 along with ⟨ɨ ʉ⟩.

- ^ The 1905 Exposé des principes and 1912 Principles mention ⟨ɵ ʚ⟩ as having been suggested in Le Maître Phonétique as alternatives to [ø œ], but not as central.

- ^ The journal was on hiatus between 1914 and 1922. I nonetheless found [ʍ] in a 1914 article, so apparently ⟨ƕ⟩ was at least not in official use right before the outbreak of World War I.

- ^ Catford (1990), who had used ⟨ɞ⟩ as open-mid in 1977, doesn't even mention the symbol and instead proposes a barred open O (a turned ⟨ꞓ⟩) be added as the symbol for the close-mid central rounded vowel. Yet Esling (1995) says "The symbol which J. C. Catford had in mind when he proposed ... in 1990 was in fact a closed reversed epsilon ([ɞ])"—I have to assume this was simply a mistake.

- ^ Passy died more than 70 years ago so I believe it's in the public domain.

- Kewitsch uses closed epsilon ʚ much earlier. Already in 1881, Kewitsch proposed ʚ in the article Internationale Alphabet in Zeitschrift für Orthographie (p. 126-130) [2] The symbol is used instead of œ by several German linguists, in the unofficial IPA they used, notably Wilhelm Viëtor along with ɵ as an alternate for ø since the 1890s. After much discussion on which to use between 1900 and 1910 (see Exposé des principes 1905 [3]), these two were eventually admitted as alternates. In 1907, Kewitsch uses ʚ for a different sounds than œ [4], and again in 1911. I don’t know when it was admitted as such but it seems to have happened between 1912 and the 2nd edition of the Exposé. If we look outside of the IPA, ꞝ was used briefly (circa 1880 to 1887) in Volapük spelling for ö, and before that in Andrew Comstock’s alphabet in 1846. --Moyogo/ (talk) 13:39, 13 February 2018 (UTC)

- Thank you for the information. What I find particularly interesting about the vowel chart in question, though, is not just the symbols per se but the phonetic values they are given (i.e. central in backness) and the fact that the same type of arrangement of vowels is not, as far as I know, seen in any other IPA (or non-IPA) publication from this period.

- Kewitsch (1907) is indeed very curious. ⟨ɜ⟩ is also seen, and, if I'm reading the chart correctly, ⟨ɜ ʚ⟩ are given the same values as the 1921 and 1993 charts. But we know this scheme was not adopted by the Association at least in 1912, so it is unlikely Kewitsch was Passy's direct inspiration for the 1921 chart, but we can certainly see an inkling there.

- I don't think it is likely that these symbols were added sometime between 1912 and 1921 only to be retracted by 1932. Especially to replace the already established ⟨ʍ⟩ with ⟨ƕ⟩ and then undo it within eleven years seems like an uncharacteristically mercurial move by the Association, so I have to assume the chart was rather a solo act by Passy (or by whoever revised L'Écriture on behalf of Passy, who by 1923 was "in retirement and fully involved with his Christian Socialist commune" [Collins & Mees 1998: 309]). Nardog (talk) 19:55, 15 February 2018 (UTC)

I somehow neglected to write a followup and proceeded to edit the article directly, but here's the belated update.

I was able to obtain L'Écriture. Turns out, it's not a book by Passy—it's just another iteration of the good-old familiar booklets credited to no particular writer, and the writing looks like Jones was largely responsible for it (as confirmed by Gimson by way of Breckwoldt 1972). It says "2e édition" on the cover and MacMahon (2010) identified it to be the second edition of the 1896 L'Écriture phonétique ; exposé populaire avec application au français et à 72 autres langues ou dialectes, but the Internet tells me there was the second edition of that book published in 1898, so MacMahon seems inaccurate in this regard—however, I don't know what the first edition of the 1921 L'Écriture phonétique internationale was.

There were many findings as I read through Collins & Mees' biography (a magnificent book). I learned that ⟨ɘ, ʚ⟩ were included in Trofimov & Jones (1923), and,

ɘ ʚ were until recently generally defunct. Jones appears to have gone on for some time using these symbols in his own teaching, and the whole set (with ʚ reversed as ɞ) cropped up again in Abercrombie (1967: 161; 177 n. 7), who stated, however, that "not all these six vowels are acknowledged by Daniel Jones" ... Recently, with the latest 1993 revision of the International Phonetic Alphabet, these symbols have achieved a second wind, and Jones could hardly have guessed that they would appear on the current 1993 IPA chart in exactly the same form as he had devised them precisely 60 years previously. (Collins & Mees 1998: 293–4)

Wells (1975: 52) also gives a valuable summary:

In 1926–7 these letters appeared briefly in the IPA Chart, though without the sanction of the Council; as Jones explained (m.f. 18.17 fn.), 'ɘ has only been included in charts for the sake of completeness. The symbol has never yet been used in practical transcriptions, ə is intended to have an elastic value which includes ɘ'. By 1928 they had disappeared from the Chart. Myself I doubt the usefulness of these symbols, finding that the symbols [ə] and [ɵ, œ], flexibly applied, are adequate.

So it seems Abercrombie was ultimately responsible for the mix-up of ⟨ʚ⟩ and ⟨ɞ⟩, perpetuated by Catford (1977) and, of course, Pullum & Ladusaw. I find it ironic that Abercrombie, who was responsible for the reversal and failed to attribute Jones as the source of the symbols in 1967, was pointing out that the symbols were included in L'Écriture in 1992, and Esling, who announced the "correction" of ⟨ʚ⟩ to ⟨ɞ⟩ as the IPA secretary in 1996, was citing the 1926 chart "to emphasize [the IPA's] consistency" in Esling (2010). Personally I would prefer ⟨ʚ⟩ because, when seen from somewhat of a distance, ⟨ɜ⟩ and ⟨ʚ⟩ look like they are facing the same direction and thus easier to recognize as related—even though I'm sure the idea is that ⟨ɞ⟩ is the "closed" version of ⟨ɜ⟩, analogous to ⟨ɘ⟩–⟨ɵ⟩. But alas, the damage has been done.

Speaking of irony, the case of ⟨![]() ⟩ and ⟨ɡ⟩ is even more tragic. In 1935, Jones was already lamenting that "our agitation in favour of the form ɡ for the ordinary letter

⟩ and ⟨ɡ⟩ is even more tragic. In 1935, Jones was already lamenting that "our agitation in favour of the form ɡ for the ordinary letter ![]() has been a complete failure", expressing "I think it would be well for our Council to consider seriously the possibility of reverting to the use of

has been a complete failure", expressing "I think it would be well for our Council to consider seriously the possibility of reverting to the use of ![]() for the ordinary ɡ-sound" (Maître Phonetique 1935: 44–51), which would be followed by the 1948 decision that they are equivalent and may be used to distinguish ordinary and advanced velar plosives in languages such as Russian. However, Jones somehow failed to address the equivalency and only mentioned the alternation for Russian etc. in the 1949 Principles, adding to the confusion. Pullum & Ladusaw missed the 1948 decision as well as its reaffirmation in 1993 (for the 1996 2nd edition), perpetuating the rather pointless adherence to ⟨ɡ⟩ well into the 21st century. Had they known about these decisions by the IPA Council, they might have not even added ⟨ɡ⟩ in Unicode... Nardog (talk) 22:00, 22 June 2018 (UTC)

for the ordinary ɡ-sound" (Maître Phonetique 1935: 44–51), which would be followed by the 1948 decision that they are equivalent and may be used to distinguish ordinary and advanced velar plosives in languages such as Russian. However, Jones somehow failed to address the equivalency and only mentioned the alternation for Russian etc. in the 1949 Principles, adding to the confusion. Pullum & Ladusaw missed the 1948 decision as well as its reaffirmation in 1993 (for the 1996 2nd edition), perpetuating the rather pointless adherence to ⟨ɡ⟩ well into the 21st century. Had they known about these decisions by the IPA Council, they might have not even added ⟨ɡ⟩ in Unicode... Nardog (talk) 22:00, 22 June 2018 (UTC)

IPA markup for charts

[edit]It is strange to see even non-IPA parts of the article's charts in the IPA font defined in my global wiki stylesheet. I would very much prefer a clear distinction between metalanguage and object language. Love —LiliCharlie (talk) 18:42, 3 September 2018 (UTC)

- Thanks Nardog for correcting this. Love —LiliCharlie (talk) 04:38, 8 September 2018 (UTC)

1900 and 1904 charts: [ꜰ ʋ] overlap with [ɥ]

[edit]In my Firefox browser the symbols [ꜰ ʋ] don't immediately follow [f v] (as in the 1921 chart) but overlap with [ɥ] of the following line. Is this an HTML syntax error? Love —LiliCharlie (talk) 04:35, 8 September 2018 (UTC)

- @LiliCharlie: Perhaps I should use div instead of span? Do the following cells appear differently for you?

- f vꜰ ʋʍ w ɥf vꜰ ʋʍ w ɥ

- Nardog (talk) 04:48, 8 September 2018 (UTC)

- No, they look the same. The trouble probably comes from the

float: right;styling which is interpreted by the Firefox engine as referring to the end of the table cell, not the end of the division/paragraph. Love —LiliCharlie (talk) 05:00, 8 September 2018 (UTC)- @LiliCharlie: I hope it's fixed now. Nardog (talk) 05:38, 8 September 2018 (UTC)

- Yes it is. Tausend Dank for your efforts. Love —LiliCharlie (talk) 06:26, 8 September 2018 (UTC)

- @LiliCharlie: I hope it's fixed now. Nardog (talk) 05:38, 8 September 2018 (UTC)

- No, they look the same. The trouble probably comes from the

Further reading / references on Kiel convention

[edit]Before International Phonetic Association Kiel Convention got merged with the present article, I had gathered a few JIPA papers about that conference and added them as Further Readings. For convenience, here are papers about or presented at that conference which are not yet used in the article.

- International Phonetic Association (1988). "The 1989 Kiel Convention". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 18 (2): 60–109.

- Ladefoged, Peter (1988). "The 1989 Kiel Convention". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 18 (2): 60–61. doi:10.1017/S0025100300003613.

- "Coordinators for the 1989 Kiel Convention". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 18 (2): 62–64. 1988. doi:10.1017/S0025100300003625.

- Bladon, Anthony (1988). "Editorial note to the coordinators' reports". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 18 (2): 65. doi:10.1017/S0025100300003637.

- Abramson, Arthur S. (1988). "1. The principles on which the IPA should be based". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 18 (2): 66–68. doi:10.1017/S0025100300003649.

- Nolan, Francis (1988). "2.2 Vowels". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 18 (2): 69–74. doi:10.1017/S0025100300003650.

- Bruce, Gösta (1988). "2.3 Suprasegmental categories and 2.4 The symbolization of temporal events". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 18 (2): 75–76. doi:10.1017/S0025100300003662.

- Pullum, Geoffrey K. (1988). "4. The form of presentation of the International Phonetic Alphabet". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 18 (2): 77–84. doi:10.1017/S0025100300003674.

- Henton, Caroline G. (1988). "5. Individual symbols and diacritics". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 18 (2): 85–94. doi:10.1017/S0025100300003686.

- Macmahon, Michael (1988). "6. Past successes and failures of the IPA". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 18 (2): 95–98. doi:10.1017/S0025100300003698.

- Esling, John H. (1988). "7.1 Computer coding of IPA symbols and 7.3 Detailed phonetic representation of computer data bases". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 18 (2): 99–106. doi:10.1017/S0025100300003704.

- Bernstein, Jared (1988). "9. Recorded illustrations of the IPA". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 18 (2): 107–109. doi:10.1017/S0025100300003716.

- "The IPA 1989 Kiel Convention Workgroup 9 report: Computer Coding of IPA Symbols and Computer Representation of Individual Languages". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 19 (2): 81–82. 1989. doi:10.1017/S002510030000387X.

- International Phonetic Association (1990). "Further report on the 1989 Kiel Convention". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 20 (2): 22–24. doi:10.1017/S0025100300004205.

Hopefully these are of use to someone to expand the section on Kiel. Umimmak (talk) 21:19, 7 April 2019 (UTC)

New symbols found in the 1907 chart

[edit]The voiceless palatal fricative (now represented by ʝ) was represented by ȷ in the chart, but the symbol was removed in 1912 and a dedicated symbol wouldn't be added until 1989. Also, ɜ ʚ (currently used for open mid-central vowels) were originally used for "less wide" vowels. — Preceding unsigned comment added by Bsslover371 (talk • contribs) 16:11, 6 June 2021 (UTC)

- You mean this one? Although I don't know enough German to decipher what the article is about, it doesn't look like an official publication of the IPA. Nardog (talk) 02:30, 7 June 2021 (UTC)

- The article is about Japan, written in German IPA. I could confirm that ȷ was actually used to represent a voiced palatal fricative, as the chart is official. Proof is https://www.internationalphoneticassociation.org/IPAcharts/IPA_hist/IPA_hist_2018.html#7 Bsslover371 (talk) 17:22, 10 June 2021 (UTC)

The article is about Japan, written in German IPA.

Well, I got that ;). And that article, by Kewitsch, is where that chart appears (see "page scan"). The 1899 chart on that page is also from an article by Kewitsch. It's no proof of anything. (According to MacMahon, the 1899 article is about vowels and the 1907 one about "progress made in romanizing Japanese; description of Japanese pronunciation".) Nardog (talk) 04:12, 11 June 2021 (UTC)- I see two obscure symbols for the chart. The apostraphe was used for an uvular nasal, and a turned digit 2 was used for an uvular trill.Bsslover371 (talk) 19:23, 19 June 2021 (UTC)

- The article is about Japan, written in German IPA. I could confirm that ȷ was actually used to represent a voiced palatal fricative, as the chart is official. Proof is https://www.internationalphoneticassociation.org/IPAcharts/IPA_hist/IPA_hist_2018.html#7 Bsslover371 (talk) 17:22, 10 June 2021 (UTC)

A typographical note: That voiced palatal fricative symbol of 1907, whatever its status, has the shape of a turned serif long s (ſ) rather than a dotless j. At that time, long s was a regular German letter that contrasted with short s. — Similarly, the voiced palatal plosive symbol used to have the shape of a turned serif f. Later (when?) the horizontal bar was raised from the baseline to the height of the bar of ɨ and ʉ, and its current IPA symbol name is "Barred dotless J". Love —LiliCharlie (talk) 12:12, 11 June 2021 (UTC)

- In the 1979 chart, the bar on the symbol for the "voiced palatal plosive" was raised from the baseline to the height of the bar of ɨ and ʉ. Proof is https://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/97984.pdf, which has the 1951, 1979, and 1989 charts. — Preceding unsigned comment added by Bsslover371 (talk • contribs) 19:15, 19 June 2021 (UTC)

- It was not. JSTOR has a hi-res image of the 1979 chart and the bar is clearly at the baseline. So it's in 1989 that it was raised. Nardog (talk) 19:31, 19 June 2021 (UTC)

- Actually, the symbol was unchanged. The reason why the voiced palatal plosive looks like it was raised in the 1989 chart was because the font was different. IPA charts prior to 1989 used a font that rendered it as a turned f. Times New Roman (which is used in the 1989 chart) has the bar of the turned f raised. — Preceding unsigned comment added by Bsslover371 (talk • contribs) 01:17, 20 June 2021 (UTC)

- 1. This is not the place to discuss the vagueness of the term "symbol". It seems clear, however, that the typographical change that took place is of a kind that even laypersons can easily spot and describe. The new glyph is so different that it might have been introduced as a new letter that carries its own semantics and contrasts with the extant letter represented by a turned f. 2. What makes you think that the IPA

's Alphabet Charts and Fonts committeeselected glyphs from only one typeface for the 1989 chart, and that that typeface was Times New Roman? — It seems that the first digital version (1.00) of Times New Roman was the one that shipped with Windows 3.1, and that it defined only 220 glyphs, the glyphs necessary to represent the displayable characters of what is now Windows-1252. A number in that ballpark was also a technical limitation of early TrueType versions that MS Windows relied on. Times New Roman v. 2.00 that shipped with Windows 95 and Windows NT 4 is reported to be the first version with more glyphs, 654 to be precise. — Also note that the initial version of Unicode had not been published by 1989. Love —LiliCharlie (talk) 19:33, 20 June 2021 (UTC)- The typeface is most likely one called IPAKiel made by a company called Linguist's Software. Here, then Secretary Keating writes: "the 2005 chart uses a legacy font that is not Unicode-compliant (Linguist's Software's IPA Kiel with IPAAdditions) ... Our use of the Linguist's Software font in the pdf image of our 2005 chart is under an embedding license. In 2014 Linguists Software was being sold, and possibly would go out of business, so at that time the Association purchased several licenses-in-perpetuity for all of the firm's fonts."

- The "Alphabet Charts and Fonts committee" didn't exist until 2017, by the way. Nardog (talk) 19:45, 20 June 2021 (UTC)

- 1. This is not the place to discuss the vagueness of the term "symbol". It seems clear, however, that the typographical change that took place is of a kind that even laypersons can easily spot and describe. The new glyph is so different that it might have been introduced as a new letter that carries its own semantics and contrasts with the extant letter represented by a turned f. 2. What makes you think that the IPA

- Actually, the symbol was unchanged. The reason why the voiced palatal plosive looks like it was raised in the 1989 chart was because the font was different. IPA charts prior to 1989 used a font that rendered it as a turned f. Times New Roman (which is used in the 1989 chart) has the bar of the turned f raised. — Preceding unsigned comment added by Bsslover371 (talk • contribs) 01:17, 20 June 2021 (UTC)

- It was not. JSTOR has a hi-res image of the 1979 chart and the bar is clearly at the baseline. So it's in 1989 that it was raised. Nardog (talk) 19:31, 19 June 2021 (UTC)

English sample words 'full', 'eye', and 'how'

[edit]I'm no linguist but surely the English example words 'full', 'eye', and 'how' in the first table are at best confusing and at worst wrong. Could someone check?

For 'full', I expect /fʊl/ not /ful/. I see that /ʊ/ doesn't seem to be an option at the time, but was no distinction made? For 'eye' /aɪ/ and 'how' /haʊ/ I wish there was a note that the /a/ was only there as part of a diphthong.

Bobagem (talk) 19:05, 17 October 2021 (UTC)

- You mean in the table in the 1888 alphabet section? The same intention as that of your suggested note is already expressed by putting the letter corresponding to the phone in italics. (That is not a very reliable way, though. E.g. if I marked the personal pronoun ‘I’ in italics, it would correspond to two phones.) I wouldn't worry about the /ʊ/ in the word ‘full’, since what matters there is the letter ‘f’. But if you find it distracting, you're free to change the sample word; it doesn't seem to me that these sample words need to remain unchanged. (Caveat: I can't access the whole reference, but I think any such need should have been expressed in our article.) ◅ Sebastian 13:17, 12 January 2022 (UTC)

- No, please do not change the table as it is a quote. The source is available here, which is linked in the last section, and here, among other places. full is seen not only for ⟨f⟩ but for ⟨u⟩. The prevailing practice at the time (which lasted until around 1970) was to represent lax and tense vowels as short and long versions of the same vowels, which is why you don't see FLEECE and THOUGHT on the table either. Nardog (talk) 13:39, 12 January 2022 (UTC)

- Thanks, Nardog, I included your references accordingly. It might also help to add a note to the section like ‘the sample words are from the original, so they may not be reflecting modern distinctions.’. ◅ Sebastian 14:34, 12 January 2022 (UTC)

- No, please do not change the table as it is a quote. The source is available here, which is linked in the last section, and here, among other places. full is seen not only for ⟨f⟩ but for ⟨u⟩. The prevailing practice at the time (which lasted until around 1970) was to represent lax and tense vowels as short and long versions of the same vowels, which is why you don't see FLEECE and THOUGHT on the table either. Nardog (talk) 13:39, 12 January 2022 (UTC)

Where to put diachronic information?

[edit]The conversation at Talk:International Phonetic Alphabet#Principles of the IPA contradicting the Council of the Association? made me aware that that article's section Letter_g is largely duplicate with text here. However, that section has two advantages:

- It covers the history of this one character across the years

- It contains a nice illustration

By contrast to the first point, this article divides the information in the two sections 1949 Principles and 1993 revision, squeezing 1948 into 1949 as if it were the same. This is a case where the (mostly) chronological structure of the article is not helpful. Would it be OK to start a new section for such diachronic information? It could be called ‘History of individual issues’, ‘History of selected values’, or some such. There already is a section for Values that have been represented by different characters, but that is under the headline ‘Summary’ and consequently only has summary tables, not allowing for the prose and picture we have about the letter g. ◅ Sebastian 13:52, 12 January 2022 (UTC)

References accessible to all

[edit]user:Nardog has just reverted the addition of the two links originally provided by him above, with the rationale “Redundant to IPA 1888b”. However, as I wrote above, the links are not redundant, since the 1888b reference is behind a paywall for many of us. Moreover, the current references occur in places where they can be understood to support individual statements rather than the whole content of the section. I therefore respectfully ask for the reversion to be undone. ◅ Sebastian 14:57, 12 January 2022 (UTC)

- We cite works, not resources that allow access to them. What you did is akin to adding separate references to publisher site, author webpage, JSTOR, Google Books, etc. that host the exact same paper. So you may add either URL to

|url=in {{cite journal}} for IPA (1888b), but adding different references to the same work is something we never do and is confusing and pointless. (Also, you should get in on The Wikipedia Library.) - I don't really see how someone could mistake the reference to be only about the inline quotation when the asterisks are in the table referenced by "as follows", but you apparently did. I'm not a fan of paragraphs with the exact same reference at the end of each sentence (see WP:REPCITE), but copy the reference to the previous sentence if you really think we should. Nardog (talk) 22:04, 12 January 2022 (UTC)

- Thanks for your explanation. I agree with many of your points, in particular your first paragraph in its entirety. In your second paragraph, you write “the asterisks are in the table”, which is no doubt true – they have been there since 1888. Taken literally, that has nothing to do with the topic of this section, but I presume you meant something like “the reference is attached to the sentence about the asterisks, which follows the sentence that contains ‘as follows’.”. (Edited 09:14, 13 January 2022 (UTC): From what I see now, this belongs to the later point about the reference location, but I won't go so far as to move around sentences here.) Somewhat more relevant is your imputation that I “[apparently did] mistake the reference to be only about the inline quotation”. That is obviously not the case; search for "the whole reference" above. (If I may add my personal advice: Before you write “I don't really see”, take another look.) I agree with WP:REPCITE and am not for copying any link, only for thinking about its best location, but that's not an issue for this talk page section. Thank you for your recommendation to get in on the Wikipedia Library; I should really do that. Now this leads us to the topic of this section, which is my main concern here:

- Why do you prefer a reference that has, as its only URL, one with limited access? You could, as you nicely explain in your first paragraph, easily have added at least one of the accessible URLs to the reference. Wouldn't that be better for the majority of our readers? ◅ Sebastian 08:52, 13 January 2022 (UTC)

- Granted, you knew the existing ref was the "whole reference", but then why attach the new refs to the first sentence instead of the second? By doing that you made the ref to IPA (1888b) only about the second.

- What makes you think I "prefer a reference that has, as its only URL, one with limited access"? Adding a free-access URL to {{cite journal}} as I suggested will precisely make the reference no longer have only a limited-access link. Nardog (talk) 21:05, 13 January 2022 (UTC)

- The simple answer is that, contrary to how you're misrepresenting my statement, I couldn't see the the whole text of 1888b. I had thought that should be clear by now. But since that's germane to the main point of this section, I can expand on it some more here, if there is anything that can help you understand the situation.

- Huh? How could a deliberate edit by an experienced editor not be what the editor prefers? ◅ Sebastian 22:53, 13 January 2022 (UTC)

- When did I say you could see the whole text of 1888b? I'm just clarifying that I thought you thought the ref was only about the last sentence because you added separate refs at the end of the preceding sentence, which certainly made the preexisting ref look like only about the last sentence whether you intended or not.

- I suggested adding

either URL to

as an alternative to your edit. Nardog (talk) 23:03, 13 January 2022 (UTC)|url=in {{cite journal}} for IPA (1888b)

For the record, some of my last statements have been moved, ridding them of context. It appears that nowadays that is allowed by WP:TPOC. So I am abstaining from further discussion here and will take this page off my watchlist. ◅ Sebastian 02:47, 12 February 2022 (UTC)

- You're the one who broke up my comment and got its second and third paragraphs rid of context. Using {{Interrupted}}, your creation that does not have consensus support by the community at large, does not excuse that. If you want to make clear which part you're replying to, use {{tq}}. Nardog (talk) 16:15, 12 February 2022 (UTC)