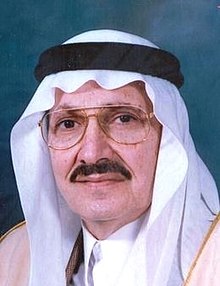

Talal bin Abdulaziz Al Saud

| Talal bin Abdulaziz Al Saud | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Minister of Communications | |||||

| In office | 1952 – April 1955 | ||||

| Predecessor | Office established | ||||

| Successor | Office abolished | ||||

| Monarch | |||||

| Born | 15 August 1931 Ta'if, Kingdom of Nejd and Hejaz | ||||

| Died | 22 December 2018 (aged 87) Riyadh, Saudi Arabia[citation needed] | ||||

| Burial | 23 December 2018 Al Oud Cemetery, Riyadh | ||||

| Spouse |

| ||||

| Issue | 15 | ||||

| |||||

| House | Al Saud | ||||

| Father | King Abdulaziz | ||||

| Mother | Munaiyir | ||||

Talal bin Abdulaziz Al Saud (Arabic: طلال بن عبد العزيز آل سعود Ṭalāl bin ʿAbdulʿazīz Āl Saʿūd; 15 August 1931 – 22 December 2018), formerly also called The Red Prince,[1] was a Saudi Arabian politician, dissident, businessman, and philanthropist. A member of the House of Saud, he was notable for his liberal stance, striving for a national constitution, the full rule of law and equality before the law. He was also the leader of Free Princes Movement in the 1960s.

Early life

[edit]

Prince Talal was born in Shubra Palace, Taif,[2] on 15 August 1931[3] as the twentieth son of King Abdulaziz.[4][5] His mother was an Armenian woman, Munaiyir, whose family escaped from the Ottoman Empire between 1915 and 1923, a period of turmoil in Armenia.[6] Munaiyir was presented by the emir of Unayza in 1921, when she was 12 years old, to the 45-year-old Abdulaziz.[6] Their first child was born when she was 15 years old, a son named Talal.[6] Following tradition, Munaiyir became known as Umm Talal, "mother of Talal". However, in 1927, the three-year-old Talal died.[6] In 1931, a second son was born to the couple, and was named Talal in honor of his late brother, following local tradition; thus, Munaiyir continued to be addressed as Umm Talal.[6] He was followed by another son, Nawwaf, and a daughter, Madawi. It is unknown when Abdulaziz divorced his fourth wife and formally wed Munaiyir.[6] She is reported by her family to have remained illiterate all her life and to have converted to Islam.[6] British diplomats in Saudi Arabia regarded Munaiyir as one of Abdulaziz's favourite wives.[7] She was as known for her intelligence as for her beauty.[7] She died in December 1991.[8]

During the reign of King Saud, Talal and Nawwaf became bitter enemies, to the point of contesting their inheritances.[9] Their full sister, Princess Madawi, died in November 2017.[10]

Positions held

[edit]Minister of Communications

[edit]Prince Talal was made minister of communications when the office was established in 1952.[11] Prince Talal became one of the wealthiest young princes, but his bureau suffered major corruption problems.[12] Then, King Abdulaziz created the ministry of the air force to represent all flight-related matters from his administration.[12] Because Prince Talal and Prince Mishaal contended over who controlled the national airlines, Saudi Arabia was to have two separate fleets.[12] The dispute ended when Prince Talal resigned in April 1955.[12] Later, the ministry of communication was merged with the ministry of finance after Prince Talal's resignation.[12] This allowed King Saud to skip choosing Talal's successor, which would have caused friction in the royal family no matter whom King Saud selected.[12]

Ambassador to France and Spain

[edit]Prince Talal served as Saudi ambassador to France and Spain between 1955 and 1957.[13]

Minister of Finance and National Economy

[edit]King Saud appointed Prince Talal as minister of finance and national economy in 1960.[14] He was removed from office on 11 September 1961.[15][16] The reason for his dismissal was his proposal to establish a constitution in Saudi Arabia in September 1961. However, King Saud had no intention or plan to reform the political system. Therefore, he forced Prince Talal to resign from the cabinet.[17] First, Prince Muhammed bin Saud[18] and then, his full brother Prince Nawwaf succeeded him in the post.[14]

Controversy

[edit]Free Princes Movement

[edit]After Prince Talal's palaces were searched by the Saudi Arabian National Guard while he was abroad, he held a press conference in Beirut on 15 August 1962. His statements caused a stir since he openly criticized and attacked the Saudi regime. As a consequence, his passport was withdrawn, his property confiscated, and some of his supporters in Saudi Arabia arrested. Soon the North Yemen Civil War began, and one week later, four crews of Saudi Arabian Airlines employees defected to Egypt. Prince Talal adopted the name of the 'Free Princes' in Cairo on 19 August 1962, and broadcast his progressive views on the Radio Cairo. Later, he, his half-brothers Fawwaz and Badr,[19] and his cousin Fahd bin Saad began to make statements on behalf of the Saudi Liberation Front. After four years, during which King Faisal offered tremendous financial inducements to the Free Princes, the latter were again reconciled with the royal family.[17]

In exile, his own family did not support him and even criticized him for his intensive sympathy with then Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser, Saudi Arabia's foremost enemy. On 8 September 1963, The Sunday Telegraph reported that Talal's mother, Munaiyir, advised her son that he was behaving foolishly while his younger sister Madawi kept asking him to return home. King Faisal reportedly refused to forgive Prince Talal but privately assured his mother that his assets would be unfrozen and that he could safely return home.[7] On 23 February 1964, Prince Talal returned to Saudi Arabia, and upon his return he issued a statement acknowledging his mistake in criticizing the Saudi government.[20]

Views

[edit]In September 1961 Prince Talal called for establishing a constitutional monarchy in Saudi Arabia[21][22] and for closing the Dhahran Air Base which had been constructed by the US. Although he served in the cabinet led by King Saud, in August 1962 Prince Talal argued that King Saud had no quality to be the ruler of the country in the 20th century.[22] Years later Prince Talal expressed his regret to form a political movement, namely Free Princes, due to the fact that it was commonly considered as a threat to the monarchy.[23]

On 6 June 1999 Prince Talal publicly reported that the Kingdom should "find a smooth way to pass the monarchy to the next generation, or face a power struggle after the era of old royals passes."[9] After the September 11 attacks, he challenged the "potentially very confusing" claim that rulers and religious scholars should jointly decide affairs of state.[24] In 2001 he openly stated his support for the establishment of an elected assembly in Saudi Arabia.[25] In September 2007, he announced his desire to form a political party to advance his goal of liberalizing the country.[26]

In 2009, Prince Talal stated, "King Abdullah is the ruler. If he wills it, it will be done."[27] However, in March 2009, he called on King Abdullah to clarify the appointment of Prince Nayef as second deputy prime minister.[28] He publicly questioned whether it would make Prince Nayef the next crown prince.[28] Prince Nayef was in fact named crown prince in October 2011 following the death of his brother, Prince Sultan. Prince Talal was a member of the Allegiance Council when the members were named in 2007. He resigned from the Council in November 2011, apparently in protest of late Prince Nayef's appointment as Crown Prince.[23] In April 2012, he said that the "hand of justice" should reach all the corrupt in Saudi Arabia, and called on the National Anti-Corruption Authority (NACA) to reach everyone, regardless of status.[29] In his June 2012 Al Quds Al Arabi interview, Prince Talal stated that the princes on the Allegiance Council were not consulted on the succession of Prince Salman and that the Council became ineffective.[21]

Various official and honorary positions

[edit]

Prince Talal was one of the members of Al Saud Family Council which consisted of royals and was established by Crown Prince Abdullah in June 2000 to discuss private issues such as business activities of princes and marriages of princess to individuals who were not member of House of Saud.[30]

Prince Talal was the chairman of Arab Gulf Program For The United Nations Development (AGFUND), which promoted socioeconomic development in the Middle East.[31][32] As part of AGFUND, he led the board of trustees of the Arab Network for NGOs based in Cairo[33] and established the Arab Open University.[32] He also supported training of women through AGFUND.[34] Through AGFUND, he provided significant monetary support for UNICEF and UNICEF declared him as its Special Envoy in 1980.[35] He became UNESCO's Special Envoy for Water in 2002 to encourage the development of safe water.[36]

Prince Talal was the president of the Arab Council for Childhood and Development.[37] He also helped create the Mentor Foundation and was an honorary member of its board of trustees.[38] He co-founded the Independent Commission for International Humanitarian Issues.[38] He was also a prominent member of the League for Development of the Pasteur Institute[38] and the honorary president of Saudi Society of Family and Community Medicine.[39]

Philanthropy

[edit]According to Riz Khan, "Prince Talal spent his post-political years developing humanitarian work, shedding the epithet 'The Red Prince' and becoming known as 'The Children's Prince' for his work with UNICEF, the United Nations Children's Fund."[40]: 39

Personal life

[edit]Prince Talal married four times. He first married Umm Faisal, who is the mother of Faisal. He later divorced her.[citation needed]

Next, Talal married Mona Al Solh, a daughter of Riad Al Solh, the first prime minister of Lebanon.[1][41] Their children are Prince Al Waleed,[41] Prince Khalid and Princess Reema.[40] They married in September 1954.[42] The marriage collapsed in 1962; they remained separated until their divorce in 1968.[40] One of his co-brothers was Prince Moulay Abdallah of Morocco, brother of King Hassan II of Morocco. Prince Abdallah of Morocco was married to another daughter of Riad Al Solh.[43] Prince Talal hired one professor from the University of Houston and an instructor to teach English, psychology and Western civilization to his daughter Reema, who was 18 years old, in Riyadh in 1976.[44]

His third wife was Moudie bint Abdul Mohsen Al Angari.[45] They had three children: a son, Turki, and two daughters, Sara and Noura. Moudie and Talal were later divorced, and she died in 2008.[45] In July 2012, their daughter Sara sought political asylum in the United Kingdom on the grounds that she was fearful for her safety in Saudi Arabia.[46]

Lastly, Talal was married to Magdah bint Turki Al Sudairi, daughter of former Human Rights Commission President Turki bin Khaled Al Sudairi.[47]

Prince Talal had a total of fifteen children, nine sons and six daughters. His sons are Faisal (died 1991), Al Waleed, Khalid, Turki, Abdulaziz, Abdul Rahman, Mansour, Mohammed and Mashour. His daughters are Reema, Sara, Noura, Al Jawhara, Hibatallah and Maha. From this information, it may be surmised that with his last wife, Magdah, he had six sons and three daughters. This may not be accurate, because he may also have had children by one or more concubines.

Death

[edit]Prince Talal bin Abdulaziz Al Saud died in Riyadh[citation needed] on 22 December 2018.[23][48] His son Prince Abdulaziz bin Talal tweeted in Arabic language: "Prince Talal bin Abdulaziz has passed away on Saturday. May God forgive him and grant him heaven".[49] Funeral prayers were held at Imam Turki bin Abdullah Mosque, Riyadh, following day.[50]

Ancestry

[edit]| Ancestors of Talal bin Abdulaziz Al Saud | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

[edit]- ^ a b Vijay Prashad (2007). The Darker Nations- A Biography of the Short-Lived Third World. New Delhi: LeftWord Books. p. 275. ISBN 978-81-87496-66-3.

- ^ "Shubra Palace: An architectural treasure house in Taif". Saudi Gazette. Taif. 26 July 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ^ "The International Who's Who: Royal Families". The International Who's Who. Routledge. Archived from the original on 5 May 2017. Retrieved 5 May 2017.

- ^ Amir Taheri (2012). "Saudi Arabia: Change Begins within the Family". The Journal of the National Committee on American Foreign Policy. 34 (3): 138–143. doi:10.1080/10803920.2012.686725. S2CID 154850947.

- ^ Jonathan Gornail (8 March 2013). "Newsmaker: Prince Al Waleed bin Talal bin Abdulaziz Al Saud". The National. Archived from the original on 1 August 2013. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g John Rossant (19 March 2002). "The return of Saudi Arabia's red prince". Online Asia Times. Hong Kong. Archived from the original on 1 October 2018. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ a b c Stig Stenslie (2011). "Power Behind the Veil: Princesses of House of Saud". Journal of Arabian Studies: Arabia, the Gulf, and the Red Sea. 1 (1): 69–79. doi:10.1080/21534764.2011.576050. S2CID 153320942.

- ^ Sharaf Sabri (2001). The House of Saud in Commerce: A Study of Royal Entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia. New Delhi: I.S. Publications. p. 126. ISBN 978-81-901254-0-6.

- ^ a b Joseph A. Kéchichian (2001). Succession in Saudi Arabia. New York: Palgrave. pp. 1, 28. ISBN 9780312238803.

- ^ David Hearst (1 January 2018). "Senior Saudi royal on hunger strike over purge". Middle East Eye. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- ^ "Brief History". Ministry of Communications and Information Technology. Archived from the original on 18 July 2012. Retrieved 31 August 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f Steffen Hertog (2011). Princes, Brokers, and Bureaucrats: Oil and the State in Saudi Arabia. Ithaca, NY; London: Cornell University Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-8014-5753-1.

- ^ Kai Bird (2010). Divided City: Coming of Age Between the Arabs and Israelis. Simon & Schuster. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-85720-019-8.

- ^ a b Yitzhak Oron, ed. (1961). Middle East Record. Vol. 2. The Moshe Dayan Center. p. 419. GGKEY:4Q1FXYK79X8.

- ^ "Chronology" (PDF). Springer. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- ^ Islam Yasin Qasem (16 February 2010). Neo-rentier theory: The case of Saudi Arabia (1950-2000) (PhD thesis). Leiden University. hdl:1887/14746.

- ^ a b Michel G. Nehme (October 1994). "Saudi Arabia 1950-80: Between Nationalism and Religion". Middle Eastern Studies. 30 (4): 930–943. doi:10.1080/00263209408701030. JSTOR 4283682.

- ^ "Saud Fires 2nd Brother". Dayton Daily News. Damascus. Associated Press. 12 September 1961. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ^ Simon Henderson (1994). "After King Fahd" (PDF). Washington Institute. Archived from the original (Policy Paper) on 17 May 2013. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ^ "Chronology December 16, 1963 - March 15, 1964". The Middle East Journal. 18 (2): 232. 1964. JSTOR 4323704.

- ^ a b "Saudi Allegiance council ineffective: Saudi prince Talal". Islam Times. 21 June 2012. Retrieved 22 June 2012.

- ^ a b "Princely Revolt". Time. Vol. 80, no. 8. 24 August 1962.

- ^ a b c Naser Al Wasmi (23 December 2018). "Saudi Arabia's Prince Talal bin Abdulaziz dies aged 87". The National. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- ^ Rachel Bronson (2005). "Rethinking Religion: The Legacy of the U.S.-Saudi Relationship". The Washington Quarterly. 28 (4): 121–137. doi:10.1162/0163660054798672. S2CID 143684653.

- ^ The Middle East and North Africa 2003 (49th ed.). London; New York: Europa Publications. 2002. p. 952. ISBN 978-1-85743-132-2.

- ^ "Saudi Arabia's Ailing Gerontocracy". David Ottoway. 1 December 2010. Archived from the original on 20 April 2014. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- ^ Abeer Allam (30 September 2010). "The House of Saud: Rulers of modern Saudi Arabia". Financial Times. Retrieved 22 July 2013.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Souhail Karam (28 March 2009). "Saudi prince questions king's deputy appointment". Reuters. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ^ Y. Admon (4 April 2012). "First Signs of Protest by Sunnis in Saudi Arabia". MEMRI. Retrieved 5 April 2012.

- ^ Simon Henderson (August 2009). "After King Abdullah. Succession in Saudi Arabia" (PDF). Policy Focus. 96. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 February 2017. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- ^ "AGFUND contributes in the relief effort for the stranded on the Libyan border". AGFUND. 7 March 2011. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ^ a b "Arab Open University". Archived from the original on 24 March 2012. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- ^ "Civil Society Development". AGFUND. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- ^ "Prince Talal heads the meetings of the trustees of CAWTAR and the "Five Sisters" committee in Tunisia". AGFUND. 14 December 2009. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- ^ "Partnership with AGFUND". UNICEF. Archived from the original on 25 September 2012. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- ^ "UNESCO Special Envoy for Water". UNESCO. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- ^ "ACCD's President". Arab Council for Childhood and Development. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- ^ a b c "HRH Prince Talal Bin Abdulaziz Al Saud". The Mentor Foundation. Archived from the original on 18 March 2012. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- ^ "Prince Talal bin Abdulaziz to Patronize Medical Conference". Saudi Press Agency. 3 February 2010. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- ^ a b c Riz Khan. (2005). Alwaleed: Businessman, Billionaire, Prince. New York: William Morrow, pp. 17-19.

- ^ a b Simon Henderson (27 August 2010). "The Billionaire Prince". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 13 October 2012. Retrieved 21 October 2012.

- ^ "Trinkets from Talal". Time Magazine. 64 (12). 20 September 1954.

- ^ Samir Bennis (3 April 2019). "The Moroccan-Saudi Rift: The Shattering of a Privileged Political Alliance" (Report). Al Jazeera Centre for Studies. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- ^ "Arab prince brought college to daughter". The Milwaukee Sentinel. 21 October 1976. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- ^ a b "Royal rivalries force princess into exile; Sara bint Talal bin Abdulaziz claims political asylum in Britain". The Ottawa Citizen. 9 July 2012. ProQuest 1024460632. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ^ Hugh Miles; Robert Mendick (7 July 2012). "Saudi Arabia's Princess Sara claims asylum in the UK". The Telegraph. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ^ "Profiles". Saudi Gazette. 15 February 2009. Archived from the original on 9 April 2015. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ "Saudi Prince Talal bin Abdulaziz passes away aged 87". Al Arabiya. 22 December 2018. Retrieved 23 December 2018.

- ^ عبدالعزيز بن طلال (22 December 2018). "انتقل الى رحمة الله الامير طلال بن عبدالعزيز غفر الله له واسكنه فسيح جناته اليوم السبت، وسيتقبل ابناءه العزاء "للرجال والنساء" بالفاخرية، ايام الاحد، الاثنين والثلاثاء من بعد صلاة المغرب حتى صلاة العشاءرحمه الله واسكنه فسيح جناته {انا لله وانا اليه راجعون}٠١١٤٤٢٢١١١ للاستفسار". @AAzizTalal (in Arabic). Retrieved 23 December 2018.

- ^ Taha Kılıç (26 December 2018). "The Red Prince of Saudi Arabia". Yeni Şafak. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Talal bin Abdulaziz Al Saud at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Talal bin Abdulaziz Al Saud at Wikimedia Commons

- Official website, (in Arabic and English)

- 20th-century Saudi Arabian diplomats

- 20th-century Saudi Arabian businesspeople

- 20th-century Saudi Arabian politicians

- 21st-century Saudi Arabian businesspeople

- 1931 births

- 2018 deaths

- Communication ministers of Saudi Arabia

- Ambassadors of Saudi Arabia to France

- Ambassadors of Saudi Arabia to Spain

- Finance ministers of Saudi Arabia

- Economy ministers of Saudi Arabia

- Arab Open University people

- Burials at Al Oud cemetery

- People from Taif

- Saudi Arabian Arab nationalists

- Saudi Arabian dissidents

- Saudi Arabian human rights activists

- Saudi Arabian people of Armenian descent

- Saudi Arabian philanthropists

- Sons of Ibn Saud