Taenia (flatworm)

| Taenia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Taenia saginata | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Platyhelminthes |

| Class: | Cestoda |

| Order: | Cyclophyllidea |

| Family: | Taeniidae |

| Genus: | Taenia Linnaeus, 1758 |

| Type species | |

| Taenia solium | |

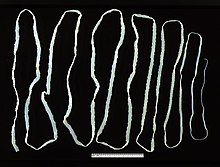

Taenia is the type genus of the Taeniidae family of tapeworms (a type of helminth). It includes some important parasites of livestock. Members of the genus are responsible for taeniasis and cysticercosis in humans, which are types of helminthiasis belonging to the group of neglected tropical diseases. More than 100 species are recorded. They are morphologically characterized by a ribbon-like body composed of a series of segments called proglottids; hence the name Taenia (Greek ταίνια, tainia meaning ribbon, bandage, or stripe). The anterior end of the body is the scolex. Some members of the genus Taenia have an armed scolex (hooks and/or spines located in the "head" region); of the two major human parasites, Taenia saginata has an unarmed scolex, while Taenia solium has an armed scolex.[1]

The proglottids have a central ovary, with a vitellarium (yolk gland) posterior to it. As in all cyclophyllid cestodes, a genital pore occurs on the side of the proglottid. Eggs are released when the proglottid deteriorates, so a uterine pore is unnecessary.

Selected species

[edit]- Taenia asiatica, the Asian taenia, has humans as definitive hosts, and pigs and rarely cattle as intermediate hosts.

- Taenia bubesei was known to infect both the lion and tiger. Though it was the Asiatic lion's range which would have overlapped with that of the tiger, rather than the African lion, two Caspian tigers in southwestern Tajikistan harbored a few tapeworms in their small and large intestines, and they had been recovered earlier from the African lion, according to Chernyshev (1953).[2]

- Taenia crassiceps usually infects canines and also rodents, but rarely infect humans.

- Taenia gonyamai is parasite of antelope (as larvae) and lions (as adults).[3]

- Taenia hydatigena uses ruminants and swine as intermediate hosts to infect mainly dogs.

- Taenia mustelae infects small carnivorans.

- Taenia ovis uses sheep as intermediate hosts to infect dogs and foxes.

- Taenia pisiformis is common in wild dogs and in rabbits, which serve as intermediate hosts.

- Taenia rileyi infects bobcats.

- Taenia saginata, beef tapeworm, infects cattle and humans, and can only reproduce while in the human gut.

- Taenia solium, pork tapeworm, like T. saginata, has humans serving as its primary host, and it can only reproduce by the dispersal of proglottids while in the gut. These reinfect pigs when human faeces are improperly disposed of. This infection is most common in parts of Africa.

- Taenia taeniaeformis uses rodents as intermediate hosts and then inhabits cats as the definitive hosts.

- Taenia serialis is a parasite of dogs and foxes which has rabbits as the intermediate host.

Life cycle

[edit]

- The life cycle begins with either the gravid proglottids or free eggs (embryophores) with oncospheres (also known as hexacanth embryos) being passed in the feces, which can last for days to months in the environment. Sometimes, these segments will still be motile upon excretion—they either empty themselves of their eggs within a matter of minutes, or in some species, retain them as a cluster and await the arrival of a suitable intermediate vertebrate host.

- The intermediate host (cattle, pigs, rodents, etc., depending on the species) must then ingest the eggs or proglottids.

- If the host is a correct one for the particular species, then the embryophores will hatch, and the hexacanth embryos will invade the wall of the small intestine of the intermediate host to travel to the striated muscles to develop into cysticerci larvae.

- Here they grow, cavitate, and differentiate into the second larval form shaped like a bladder (and erroneously believed until the middle of the 19th century to be a separate parasite, the bladderworm) which is infectious to the definitive host when an invaginated protoscolex is completely developed.

- To continue the process, the definitive host must eat the uncooked meat of the intermediate host. Once in the small intestine of the definitive host, the bladder is digested away, the scolex embeds itself into the intestinal wall, and the neck begins to bud off segments to form the strobila. New eggs usually appear in the feces of the definitive host within 6 to 9 weeks, and the cycle repeats itself.

T. saginata is about 1,000–2,000 proglottids long with each gravid proglottid containing 100,000 eggs, while T. solium contains about 1,000 proglottids with each gravid proglottid containing 60,000 eggs.[4]

Divergence of Taenia in humans

[edit]Humans were previously thought to have acquired Taenia species (T. solium, T. asiatica, and T. saginata) after the domestication of large mammals, although the omnivorous diet and foraging of early hominids suggest the contact between the ancestral Taenia was established prior to the rise of modern humans and advanced agriculture. Evidence suggests the domestication of animals by humans consequently introduced Taenia species to new intermediate hosts, cattle, and swine.[5]

Morphological and molecular data suggest that the divergence of Taenia specialised human parasites has been directly associated with earlier hominids and prior to the existence of modern Homo sapiens. Direct predator-prey relationships between humans and the original definitive and intermediate hosts of Taenia resulted in this host switch. Ecological evidence showed that early hominids preyed heavily on one of the intermediate hosts, antelope, of Taenia, thus resulting in earlier colonization by the parasite prior to mammalian domestication. The early hominids had an omnivorous diet; they were hunters and scavengers. The abundance of antelope in sub-Saharan Africa savannah in the Late Pliocene resulted in a vast food resource for hominids and other carnivorous animals such as felids, canids, and hyaenids.[5] Hominids who hunted antelopes or scavenged killed antelopes bridged the beginning of a host-parasite relationship between hominids and Taenia. During this time, hominids may not have had the means of cooking their food. This would have greatly increased their chances of catching the cysticerci, as a result of eating uncooked meat. Also, transmission of the parasite may have been enhanced by directly consuming the definitive host. Parasitological data support the foraging of antelope by Homo species during the Late Pliocene and Pleistocene periods. This corresponds to the initial contact of the ancestral Taenia and specialize into T. solium, T. saginata, and T. asiatica, thus resulting in colonization of the early hominids as definitive hosts.

Host switching for Taenia is most prevalent among carnivores and less prevalent among herbivores through cospeciation. An excess of 50–60% of Taenia colonization occurs among carnivores—hyaenids, felids, and hominids.[6] Acquisition of the parasite occurs more frequently among definitive hosts than among intermediate hosts.[6] Therefore, host switching likely could not have come from cattle and pigs. The establishment of cattle and pigs as intermediate host by Taenia species is consequently due to the synanthropic relationship with humans. During the past 8,000–10,000 years, the colonization of respective Taenia species from humans to cattle and to swine was established.[6] In contrast, the colonization of ancestral Taenia onto the early hominids was established 1.0–2.5 million years ago.[6] It clearly shows that the colonization of human Taenia antedates the domestication of mammals.

References

[edit]- ^ Roberts, L.S. and Janovy, John Jr. Foundations of Parasitology 7th Edition. McGraw-Hill. 2005.

- ^ Heptner, V. G.; Sludskij, A. A. (1992) [1972]. Mlekopitajuščie Sovetskogo Soiuza. Moskva: Vysšaia Škola [Mammals of the Soviet Union. Volume II, Part 2. Carnivora (Hyaenas and Cats)]. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution and the National Science Foundation. pp. 1–732.

- ^ Sachs, R (1969). "Untersuchungen zur Artbestimmung und Differenzierung der Muskelfinnen ostafrikanischer Wildtiere". Zeitschrift für Tropenmedizin und Parasitologie (in German). 20 (1): 39–50.

- ^ "Taeniasis". DPDx - Laboratory Identification of Parasitic Diseases of Public Health Concern. 29 November 2013. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- ^ a b Hoberg, E. P.; Alkire, N. L.; Queiroz, A. D.; Jones, A. (2001). "Out of Africa: origins of the Taenia tapeworms in humans". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 268 (1469): 781–787. doi:10.1098/rspb.2000.1579. PMC 1088669. PMID 11345321.

- ^ a b c d Hoberg, Eric P. (2006). "Phylogeny of Taenia: Species definitions and origins of human parasites". Parasitology International. 55: S23 – S30. doi:10.1016/j.parint.2005.11.049. PMID 16371252.