Symphony No. 3 (Tchaikovsky)

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky's Symphony No. 3 in D major, Op. 29, was written in 1875. He began it at Vladimir Shilovsky's estate at Ussovo on 5 June and finished on 1 August at Verbovka. Dedicated to Shilovsky, the work is unique in Tchaikovsky's symphonic output in two ways: it is the only one of his seven symphonies (including the unnumbered Manfred Symphony) in a major key (discounting the unfinished Symphony in E♭ major); and it is the only one to contain five movements (an additional Alla tedesca movement occurs between the opening movement and the slow movement).

The symphony was premiered in Moscow on 19 November 1875, under the baton of Nikolai Rubinstein, at the first concert of the Russian Music Society's season. It had its St. Petersburg premiere on 24 January 1876, under Eduard Nápravník. Its first performance outside Russia was on 8 February 1879, at a concert of the New York Philharmonic Society.

Its first performance in the United Kingdom was at the Crystal Palace in 1899, conducted by Sir August Manns, who seems to have been the first to refer to it as the "Polish Symphony", in reference to the recurring Polish dance rhythms prominent in the symphony's final movement. Several musicologists, including David Brown and Francis Maes, consider this name a faux pas. Western listeners, conditioned by Chopin's use of the polonaise as a symbol of Polish independence, interpreted Tchaikovsky's use of the same dance likewise; actually, in Tsarist Russia it was musical code for the Romanov dynasty and, by extension, Russian imperialism.

The symphony was used by George Balanchine as the score for the Diamonds section of his full length 1967 ballet Jewels, omitting the opening movement.

Instrumentation

[edit]The Symphony is scored for an orchestra comprising piccolo, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets (in A, B-flat), 2 bassoons, 4 horns (in F), 2 trumpets (in F), 3 trombones, tuba, 3 timpani and strings (violins I, violins II, violas, cellos, and double basses).

On the symphony's instrumentation, musicologist Francis Maes writes that here, Tchaikovsky's "feeling for the magic of sound is revealed for the first time" and likens the music's "sensual opulence" to the more varied and finely shaded timbres of the orchestral suites.[1] Wiley adds about this aspect, "Is the symphony a discourse or the play of sound? It revels in the moment."[2]

Form

[edit]Like Robert Schumann's Rhenish Symphony, the Third Symphony has five movements instead of the customary four in a suite-like formal layout, with a central slow movement flanked on either side by a scherzo.[3] The work also shares the Rhenish's overall tone of exuberant optimism.[1] For these reasons, musicologist David Brown postulates that Tchaikovsky might have conceived the Third Symphony with the notion of what Schumann might have written had he been Russian.[4][a 1] The Rhenish, in fact, was one of two works that had most impressed Tchaikovsky during his student days at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory; the other was the Ocean Symphony by his teacher, Anton Rubinstein.[5]

The average performance of this symphony runs about 45 minutes.[6]

- Introduzione e Allegro: Moderato assai (Tempo di marcia funebre) (D minor) — Allegro briliante (D major)

- This movement, in common time, begins with a slow funeral march opening in the parallel minor. The movement then accelerandos and crescendos up to a key change back into the parallel major, where, in a typical sonata-allegro form, after the exposition in the major key it modulates to the dominant (A major), before repeating the theme from the key change and then returning to the tonic at the end instead of the dominant, with a developmental section in between before the recapitulation. The movement closes with a coda, which occurs twice (essentially back to back) and accelerandos to an extremely fast tempo towards the very end.

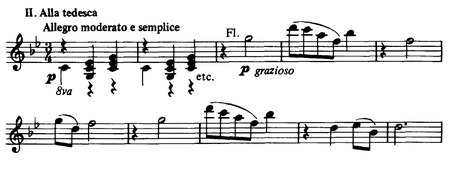

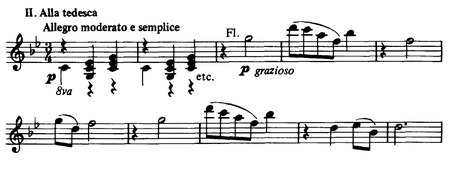

- Alla tedesca: Allegro moderato e semplice (B♭ major→G minor)

- In a sort of ternary form, this begins as a waltz, and then after a trio consisting of a many-times-repeated triplet eighth note figure in the winds and strings, after which the beginning up to the trio is basically repeated again. The movement closes with a brief coda consisting of string pizzicatos and clarinet and bassoon solos.

- Andante elegiaco (D minor→B♭ major→D major)

- Also in 3

4 time, this movement opens with all winds, notably a flute solo. This movement is the most romantic in nature of the five, and it is roughly a variation of slow sonata ternary form without a development, although the traditional dominant-tonic recapitulation is abandoned for more distant keys, the first being in B♭ major (the subdominant to F) and the recapitulation in D major (the parallel major to D minor). This movement is atypically more lyrical than the second. Between the two is a contrasting middle section, consisting of material closely resembling the repeated eighth note triplet figures in the trio of the second movement. The movement closes with a brief coda with string tremolos, and a repeat of the wind solos accompanied by string pizzicatos from the opening of the movement.

- Also in 3

- Scherzo: Allegro vivo (B minor)

- The scherzo is in 2

4 time. This is somewhat unusual, as scherzi in classical music of the time are traditionally in triple meter, although the name scherzo (literally meaning 'joke' in Italian) does not in itself imply this metric convention. Like other scherzi of its time, the movement is fast enough to be conducted in one and is composed in ternary form. After a prolonged 'question and answering' of sixteenth note figures between the upper strings and woodwinds, there is a trio in the form of a march, which modulates through a number of different keys, starting with G minor, before returning to the relative major to the tonic B minor of the movement, D major. The entire opening of the movement up to the trio is then repeated, and the movement closes with a brief reprise of some of the trio's march material. The trio uses material Tchaikovsky had composed for an 1872 cantata to celebrate the bicentenary of the birth of Tsar Peter the Great. The entire movement has muted strings, and there is a trombone solo at the exposition before the trio and the recapitulation after the trio, the only appearance of the trombone in the symphony outside the first and last movements.

- The scherzo is in 2

- Finale: Allegro con fuoco (Tempo di polacca) (D major)

- This movement is characterized by rhythms typical of a polonaise, a Polish dance, from which the symphony draws its name. The opening theme is effectively a variety of a rondo theme, and it returns several more times in the movement, with different episodes in between each occurrence: the first is fugal, the second is a wind-choral, and the third is a section in the relative minor, B minor, where some of the second movement's trio's triplet figures make another reprise. There is then another longer fugal section, a variation of the main theme which modulates into a number of different keys along the way. It is characterized by staggered entrances of the theme, before another variation on another reprise of the main theme slows dramatically into a slower chorale section featuring all the winds and brass. There is then a section with another variation on the original theme up to the original tempo, and then a presto in 1 which drives to the end, which concludes with 12 D major chords over a long timpani roll, and then 3 long Ds, the third of which is a fermata in the very last bar of the symphony.

Analysis

[edit]In his biography and analysis of Tchaikovsky's music, Roland John Wiley likens the five-movement format to a divertimento and questions whether Tchaikovsky wanted to allude in this work to the 18th century.[2] Rosa Newmarch mentions the 3rd Symphony in D is a work altogether different in style to his two earlier ones, and totally western in character.[7] Such a move would not be unique or unprecedented in Tchaikovsky's work; David Brown points out in the 1980 edition of the New Grove that the composer occasionally wrote in a form of Mozartian pastiche throughout his career.[8] (The Variations on a Rococo Theme for cello and orchestra, which Wiley suggests by Tchaikovsky's use of the word Rococo in the title is his "first nominal gesture toward 18th century music," is in fact a near-contemporary of the symphony.)[9] Musicologist Richard Taruskin made a similar statement by calling the Third Symphony 'the first 'typical' [Tchaikovsky] symphony (and the first Mozartean one!) in the sense that it is the first to be thoroughly dominated by the dance."[10]

In explaining his analogy, Wiley points out how the composer holds back the full orchestra occasionally in a manner much like that of a concerto grosso, "the winds as concertino to the ripieno of the strings" in the first movement, the waltz theme and trio of the second movement and the trio of the fourth movement (in other words, the smaller group of winds balanced against the larger group of strings).[2] The finale, Wiley states, does not decide which format Tchaikovsky may have actually had in mind. By adding a fugue and a reprise of the movement's second theme in the form of a recapitulation to the opening polonaise, Wiley says Tchaikovsky concludes the work on a note "more pretentious than a divertimento, less grand than a symphony, [and] leaves the work's genre identity suspended in the breach."[2]

For other musicologists, the Schumannesque formal layout has been either a blessing or a curse. John Warrack admits the second movement, Alla tedesca, "balances" the work but he nonetheless senses "the conventional four-movement pattern being interrupted" unnecessarily, not amended in an organic manner.[11] Brown notes that if Tchaikovsky amended the four-movement pattern because he felt it no longer adequate, his efforts proved unsuccessful.[12] Hans Keller disagrees. Rather than a "regression" in symphonic form, Keller sees the five-movement form, along "with the introduction of dance rhythms into the material of every movement except the first," as widening "the field of symphonic contrasts both within and between movements."[13]

Composition and initial performances

[edit]Tchaikovsky recorded little about the composition of his Third Symphony. He penned the work quickly, between June and August 1875.[14] After its premiere, he wrote Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, "As far as I can see this symphony presents no particularly successful ideas, but in workmanship it's a step forward."[15] Not long before composing this symphony, Tchaikovsky had received a thorough drubbing from Nikolai Rubinstein over the flaws in his First Piano Concerto, the details of which he would later recount to his patroness, Nadezhda von Meck. This incident may have influenced Tchaikovsky to be more cautious in following academic protocol, at least in the symphony's outer movements.[16]

The symphony was premiered in Moscow in November 1875 under the baton of the composer's friend and champion, Nikolai Rubinstein. Tchaikovsky, who attended rehearsals and the performance, was "generally satisfied" but complained to Rimsky-Korsakov that the fourth movement "was played far from well as it could have been, had there been more rehearsals."[17] The first performance in Saint Petersburg, given in February 1876 under Eduard Nápravník, "went off very well and had a considerable success," in the composer's estimation.[18] Nápravník, who had conducted the first performance of the revised overture–fantasia Romeo and Juliet three years earlier,[19] would become a major interpreter of Tchaikovsky's music. He would premiere five of the composer's operas[20] and, among many traversals of the orchestral works, conduct the first performance of the Pathétique symphony after Tchaikovsky's death.[21]

The first performance of the Third outside Russia was scheduled for October 1878 with the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra under Hans Richter.[22] Richter, an admirer of Tchaikovsky's work, had already conducted Romeo and Juliet there in November 1876.[23] However, after the symphony had been rehearsed, the Philharmonic Society cancelled the performance, citing the work's apparent difficulty and lack of public familiarity with the composer.[22] The fact that Romeo had been hissed by the audience and unfavorably reviewed by Eduard Hanslick might have also contributed to its decision.[23]

The British premiere of the Third Symphony was led by Sir August Manns at the Crystal Palace in London in 1899.[1] Manns dubbed the work with the sobriquet Polish at that time.[14]

Critical opinion

[edit]The initial critical response to the Third Symphony in Russia was uniformly warm.[24] However, over the long run, opinion has remained generally mixed, leaning toward negative. Among musicologists, Martin Cooper considers it "the weakest, most academic" of the seven the composer completed.[25] Warrack notes a disjunction between the work's various musical elements. He writes that it "lacks the individuality of its fellows" and notes "a somewhat awkward tension between the regularity of a symphonic form he was consciously trying to achieve in a 'Germanic' way and his own characteristics."[14] Wiley, less polarizing, calls the Third the "least comformative" of the symphonies and admits its unorthodox structure and wide range of material "may produce an impression of strangeness, especially of genre."[26] These factors, he says, make the Third difficult to categorize: "It is not folkish, nor classical, nor Berliozian/Lisztian, nor particularly Tchaikovskian in light of his other symphonies."[26]

On the positive side of the spectrum, Keller calls the Third Symphony the composer's "freest and most fluent so far"[3] and Maes dismisses naysayers of the piece as those who judge the quality of a Tchaikovsky composition "by the presence of lyric charm, and [reject] formal complexity ... as incompatible with the alleged lyric personality of the composer."[1] Maes points out the symphony's "high degree of motivic and polyphonic intricacies," which include the composer's use of asymmetrical phrases and a Schumannesque play of hemiolas against the normal rhythmic pattern of the first movement.[1] He also notes the Third's "capricious rhythms and fanciful manipulation of musical forms,"[1] which presage the music Tchaikovsky would write for his ballets (his first, Swan Lake, would be his next major work) and orchestral suites.[1] Wiley seconds the stylistic nearness to the orchestral suites and notes that the creative freedom, beauty and lack of apparent internal logic between movements which is characteristic of those compositions also seems apparent in the symphony.[2]

Occupying the middle ground between these extremes, Brown deems the Third "the most inconsistent ... least satisfactory" of the symphonies[27] and "badly flawed"[28] but admits it is "not so devoid of 'particularly successful ideas' as the composer's own judgment would have us believe."[27] He surmises that Tchaikovsky, caught between the proscriptions of sonata form and his own lyric impulses, opted for the latter and "was at least wise enough not to attempt an amalgamation" of academic and melodic veins, which fundamentally worked against each other.[29] The best parts of the symphony, he continues, are the three inner movements, where the composer allowed his gift for melody "its full unfettered exercise."[29] Brown says the symphony "discloses the widening dichotomy within Tchaikovsky's style, and powerfully proclaims the musical tensions that matched those within the man himself."[29]

Controversy over the nickname "Polish"

[edit]Western critics and audiences began calling this symphony the Polish after Sir August Manns led the first British performance in 1899, with the finale seen as an expression by the Polish people for their liberation from Russian domination and the reinstatement of their independence.[1] Since this was the way Chopin had treated the dance in his works and people had heard them in that light for at least a generation, their interpretation of the finale of the Third Symphony in a similar manner was completely understandable. Unfortunately, it was also completely wrong.[1]

In Tsarist Russia, the polonaise was considered musical code for the Romanov dynasty and a symbol of Russian imperialism[citation needed]. In other words, Tchaikovsky's use of the polonaise was the diametric opposite to Chopin's.[30] This context for the dance began with Osip Kozlovsky (1757–1831) (Polish: Józef Kozłowski), a Pole who served in the Russian army and whose greatest successes as a composer were with his polonaises. To commemorate Russian victory over the Ottoman Empire in Ukraine, Kozlovsky wrote a polonaise entitled "Thunder of Victory, Resound!" This set the standard for the polonaise as the preeminent genre for Russian ceremony.[31]

One thing to keep in mind is that Tchaikovsky lived and worked in what was probably the last 19th-century feudal nation. This made his creative situation more akin to Mendelssohn or Mozart than to many of his European contemporaries.[32] Because of this cultural mindset, Tchaikovsky saw no conflict in making his music accessible or palatable to his listeners, many of whom were among the Russian aristocracy and would eventually include Tsar Alexander III.[33] He remained highly sensitive to their concerns and expectations and searched constantly for new ways to meet them. Part of meeting his listeners' expectations was using the polonaise, which he did in several of his works, including the Third Symphony. Using it in the finale of a work could assure its success with Russian listeners.[34]

Use in Jewels

[edit]The symphony, without its first movement, was used by choreographer George Balanchine for Diamonds, the third and final part of his ballet Jewels.[35] Created for the New York City Ballet, of which Balanchine was cofounder and founding choreographer, Jewels premiered on April 13, 1967 and is considered the first full-length abstract ballet.[36] Choreographed with ballerina Suzanne Farrell in mind and inspired by the unicorn tapestries in the Musée de Cluny in Paris, Diamonds was meant to evoke the work of Marius Petipa at the Imperial Russian Ballet. Petipa collaborated with Tchaikovsky on the ballets The Sleeping Beauty and The Nutcracker, hence the use of Tchaikovsky's music in Diamonds.[35]

Notes and references

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Tchaikovsky was not the only Russian composer to use Schumann in general, or the Rhenish in particular, as a model. Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov acknowledged it as a reference when, as a naval cadet, he wrote his First Symphony; the work itself is closely patterned after Schumann's Fourth.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i Maes, 78.

- ^ a b c d e Wiley, Tchaikovsky, 133.

- ^ a b Keller, 344.

- ^ Brown, Crisis, 44; Maes, 78.

- ^ Brown, Early, 63–4.

- ^ Cummings, allmusic.com.

- ^ Newmarch, Rosa (1908) [1899]. Tchaikovsky His Life and Works (Revised ed.). New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. p. 51. ISBN 978-0838303108.

- ^ Brown, New Grove (1980), 18:628.

- ^ Wiley, Tchaikovsky, 143.

- ^ Taruskin, Russian, 130.

- ^ Warrack, Symphonies, 20–1.

- ^ Brown, Final, 441.

- ^ Keller, 344–5.

- ^ a b c Warrack, Symphonies, 20.

- ^ As quoted in Brown, Crisis, 42.

- ^ Brown, Crisis, 42.

- ^ As quoted in Brown, Crisis, 52.

- ^ As quoted in Brown, Crisis, 61.

- ^ Brown, Early, 186.

- ^ Brown, Early, 226.

- ^ Brown, Final, 487.

- ^ a b Brown, Crisis, 241.

- ^ a b Brown, Crisis, 102.

- ^ Brown, Crisis, 66.

- ^ Cooper, 30.

- ^ a b Wiley, Tchaikovsky, 132.

- ^ a b Brown, Crisis, 50.

- ^ Brown, Final, 150.

- ^ a b c Brown, Crisis, 30.

- ^ Figes, 274; Maes, 78–9, 137.

- ^ Maes, 78–9.

- ^ Figes, 274; Maes, 139–41.

- ^ Maes, 137; Taruskin, Grove Opera, 4:663.

- ^ Maes, 137.

- ^ a b Potter. "Company premiere of Jewels, BalletMet Columbus at the Ohio Theatre". Retrieved 2013-02-12.

- ^ Reynolds, 247.

Bibliography

[edit]- Brown, David, "Tchaikovsky, Pyotr Ilyich." In The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (London: MacMillan, 1980), 20 vols., ed. Sadie, Stanley. ISBN 0-333-23111-2.

- Brown, David, Tchaikovsky: The Early Years, 1840–1874 (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1978). ISBN 0-393-07535-2.

- Brown, David, Tchaikovsky: The Crisis Years, 1874–1878, (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1983). ISBN 0-393-01707-9.

- Brown, David, Tchaikovsky: The Final Years, 1885–1893, (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1991). ISBN 0-393-03099-7.

- Cooper, Martin, "The Symphonies." In Music of Tchaikovsky (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1945), ed. Abraham, Gerald. ISBN n/a.

- Cummings, Robert, Description of Tchaikovsky Symphony No. 3, allmusic.com. Accessed 17 Mar 2012.

- Figes, Orlando, Natasha's Dance: A Cultural History of Russia (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2002). ISBN 0-8050-5783-8 (hc.).

- Keller, Hans, "Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky." In The Symphony (New York: Drake Publishers Inc., 1972), 2 vols., ed. Simpson, Robert. ISBN 0-87749-244-1.

- Maes, Francis, A History of Russian Music: From Kamarinskaya to Babi Yar (Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press, 2002), tr. Pomerans, Arnold J. and Erica Pomerans. ISBN 0-520-21815-9.

- Potter, Jeannine, Program notes for Jewels, BalletMet Columbus, Sep 2003. Accessed 17 Mar 2012.

- Reynolds, Nancy, Repertory in Review (New York: Dial Press, 1977).

- Taruskin, Richard, "Tchaikovsky, Pyotr Il'yich", The New Grove Dictionary of Opera (London and New York: Macmillan, 1992), 4 vols, ed. Sadie, Stanley. ISBN 0-333-48552-1.

- Taruskin, Richard, On Russian Music (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2009). ISBN 0-520-26806-7.

- Warrack, John, Tchaikovsky Symphonies and Concertos (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1969). Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 78–105437.

- Wiley, Roland John, The Master Musicians: Tchaikovsky (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2009). ISBN 978-0-19-536892-5.