Swift Current

Swift Current | |

|---|---|

| City of Swift Current | |

| |

| Nicknames: | |

| Motto: Where Life Makes Sense | |

| Coordinates: 50°17′17″N 107°47′38″W / 50.28806°N 107.79389°W | |

| Country | Canada |

| Province | Saskatchewan |

| Established | 1883 |

| Incorporated (village) | September 21, 1903 |

| Incorporated (town) | March 15, 1907 |

| Incorporated (city) | January 15, 1914 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Al Bridal |

| • Governing body | Swift Current City Council |

| • MP | Jeremy Patzer |

| • MLA | Everett Hindley |

| Area | |

| • Land | 29.31 km2 (11.32 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 817 m (2,680 ft) |

| Population (2021) | |

• Total | 16,750 [2] |

| • Agglomeration | 18,536 |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (CST) |

| Forward sortation area | |

| Website | www |

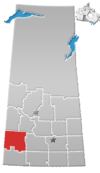

Swift Current is the sixth-largest city in the Canadian province of Saskatchewan. It is situated along the Trans Canada Highway 177 kilometres (110 mi) west of Moose Jaw, and 223 kilometres (139 mi) east of Medicine Hat, Alberta. As of 2024, Swift Current has an estimated population of 18,430, a growth of 1.32[4]% from the 2016 census population of 16,604.[5] The city is surrounded by the Rural Municipality of Swift Current No. 137.

History

[edit]

Swift Current's history began with Swift Current Creek which originates at Cypress Hills and traverses 160 kilometres (99 mi) of prairie and empties into the South Saskatchewan River at Lake Diefenbaker. The creek was a camp for First Nations for centuries. The name of the creek comes from the Cree, who called the South Saskatchewan River Kisiskâciwan, meaning "it flows swiftly". Fur traders found the creek on their westward treks in the 1800s, and called it "rivière au Courant" (lit: "river of the current"). Henri Julien, an artist travelling with the North-West Mounted Police expedition in 1874, referred to it as "Du Courant", and Commissioner George French used "Strong Current Creek" in his diary. While it took another decade before being officially recorded, the area has always been known as "Swift Current".[6]

The settlement of Swift Current was established in 1883, after the CPR surveyed a railway line as far as Swift Current Creek. In 1882, initial grading and track preparation commenced, with the first settlers arriving in the spring of 1883. During the early part of its settlement, the economy was based almost exclusively on serving the new railway buildings and employees. There was also a significant ranching operation known as the "76" ranches. It included 10 ranches raising sheep and cattle and stretched from Swift Current to Calgary. The ranch located at Swift Current dealt with sheep. At one point there were upwards of 20,000 sheep grazing on the present day Kinetic Grounds. The head shepherd was John Oman, originally from Scotland. He donated land to build Oman School in 1913.[7] Other early industries included gathering bison bones for use in fertilizer manufacturing, the making of bone china and sugar refining. Métis residents also ran a successful Red River ox cart "freighting" business along the Swift Current-Battleford Trail to Battleford until the late 1880s. During the Riel Rebellion of 1885, Swift Current became a major military base and troop mustering area due to its proximity to Battleford but this was only for a short time. On February 4, 1904, the hamlet became a village and then a town on March 15, 1907, when a census indicated a population of 550. Swift Current became incorporated as a city on January 15, 1914, with Frank E. West being the mayor at the time.

During World War II, the United Kingdom was considered an unsuitable site for training pilots. The British Commonwealth Air Training Plan identified the Canadian Prairies, with their clear weather and great distance from enemy territory, as an ideal alternative. In 1941, the No. 39 Service Training Flying School was constructed east of Swift Current, hosting over one thousand servicemen at all times until its closure in March 1944.[8] Today, the facility is maintained as the Swift Current Airport, and was taken over by the city of Swift Current from Transport Canada in 1996. Airport services were then contracted out. There have been recent (2005–2006) plans to expand and revitalize the airport alongside the rural municipalities surrounding Swift Current.

Oil was discovered at Fosterton in 1952, 30 miles northwest of the city. This first well continued to pump oil for over 40 years. Since then, with almost 4,000 wells completed in the area, the Shaunavon Formation has yielded 500 million barrels in total production.[9]

Swift Current is affectionately known as "Speedy Creek", a synonymous play on words. This phrase occurs in the name of many local businesses and organizations. As the primary service centre for most of Southwestern Saskatchewan, its name is also frequently contracted to "Swift" or "Swifty".

Landmarks

[edit]

Swift Current is home to Saskatchewan's oldest operating theatre: the Lyric Theatre, built in 1912 at a cost of $50,000 is the "crown jewel" of Swift Current's historical downtown buildings, with instantly recognizable advertisements painted on the north and south sides of the building dating back to the early 1920s. The building has served many functions over the years: at first it housed glamorous vaudeville performances by traveling companies, was later converted into a movie theatre and, in the mid-1980s, a bar and nightclub. A volunteer non-profit group (Southwest Cultural Development Group) purchased the facility in 2005 and is raising money for its preservation while staging cultural events, such as a mock Chautauqua annually in July, since 2008, open mic nights throughout the year, and administering rentals of the building. The current musician in residence is Al Hudec.

Swift Current's tallest commercial building is the EI Wood Building, located downtown.

The longest running business in Swift Current is the Imperial Hotel, also known as "The Big Eye" due to the large eye painted on the side. It was built in 1903 and was used as evidence that Swift Current should be granted village status. The owner, R.H. Corbett of Medicine Hat, needed the designation to obtain a liquor licence.[10]

The Swift Current railway station has been designated a historic railway station in 1991. [11] The Court House is also a designated historical building.

Swift Current is located at the start of the historic Swift Current-Battleford Trail, the remnants of which can still be seen today at the Battleford Trail Ruts Heritage Site.

Demographics

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1901 | 121 | — |

| 1906 | 554 | +357.9% |

| 1911 | 1,852 | +234.3% |

| 1916 | 3,181 | +71.8% |

| 1921 | 3,518 | +10.6% |

| 1926 | 4,175 | +18.7% |

| 1931 | 5,296 | +26.9% |

| 1936 | 5,074 | −4.2% |

| 1941 | 5,594 | +10.2% |

| 1946 | 6,379 | +14.0% |

| 1951 | 7,458 | +16.9% |

| 1956 | 10,612 | +42.3% |

| 1961 | 12,186 | +14.8% |

| 1966 | 14,485 | +18.9% |

| 1971 | 15,415 | +6.4% |

| 1976 | 14,264 | −7.5% |

| 1981 | 14,747 | +3.4% |

| 1986 | 15,666 | +6.2% |

| 1991 | 14,815 | −5.4% |

| 1996 | 14,890 | +0.5% |

| 2001 | 14,821 | −0.5% |

| 2006 | 14,946 | +0.8% |

| 2011 | 15,503 | +3.7% |

| 2016 | 16,264 | +4.9% |

| 2021 | 16,304 | +0.2% |

| Source: Statistics Canada [12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][3] | ||

In the 2021 Census of Population conducted by Statistics Canada, Swift Current had a population of 16,750 living in 7,214 of its 7,891 total private dwellings, a change of 0.9% from its 2016 population of 16,604. The city's official webpage lists the population as "approximately 18,500 people".[20] With a land area of 29.3 km2 (11.3 sq mi), it had a population density of 571.7/km2 (1,480.6/sq mi) in 2021.[21]

| 2011 | |

|---|---|

| Population | 15,503 (3.7% from 2006) |

| Land area | 24.04 km2 (9.28 sq mi) |

| Population density | 644.9/km2 (1,670/sq mi) |

| Median age | 41.9 (M: 39.8, F: 44.1) |

| Private dwellings | 7,266 (total) |

| Median household income |

Ethnicity

[edit]| Panethnic group | 2021[23] | 2016[24] | 2011[25] | 2006[26] | 2001[27] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | |

| European[a] | 13,025 | 80.7% | 13,855 | 86.46% | 13,675 | 90.23% | 14,070 | 95.58% | 13,900 | 95.04% |

| Southeast Asian[b] | 1,370 | 8.49% | 730 | 4.56% | 440 | 2.9% | 20 | 0.14% | 15 | 0.1% |

| Indigenous | 800 | 4.96% | 655 | 4.09% | 450 | 2.97% | 280 | 1.9% | 280 | 1.91% |

| South Asian | 395 | 2.45% | 210 | 1.31% | 70 | 0.46% | 120 | 0.82% | 160 | 1.09% |

| East Asian[c] | 205 | 1.27% | 295 | 1.84% | 355 | 2.34% | 165 | 1.12% | 205 | 1.4% |

| Latin American | 120 | 0.74% | 125 | 0.78% | 55 | 0.36% | 30 | 0.2% | 60 | 0.41% |

| African | 120 | 0.74% | 55 | 0.34% | 100 | 0.66% | 10 | 0.07% | 10 | 0.07% |

| Middle Eastern[d] | 30 | 0.19% | 45 | 0.28% | 0 | 0% | 30 | 0.2% | 0 | 0% |

| Other/multiracial[e] | 50 | 0.31% | 55 | 0.34% | 0 | 0% | 10 | 0.07% | 0 | 0% |

| Total responses | 16,140 | 96.36% | 16,025 | 96.51% | 15,155 | 97.43% | 14,720 | 98.49% | 14,625 | 98.68% |

| Total population | 16,750 | 100% | 16,604 | 100% | 15,554 | 100% | 14,946 | 100% | 14,821 | 100% |

| Note: Totals greater than 100% due to multiple origin responses | ||||||||||

Climate

[edit]Swift Current experiences a humid continental climate (Köppen climate classification Dfb) that does not fall far from being classified as semi-arid (Köppen BSk). Winters are long, dry, and cold, while summers are short, warm, and relatively wet, drying out in the latter part. The coldest month is January, with a mean temperature of −10.1 °C (14 °F), while the warmest month is July, with a mean temperature of 18.2 °C (65 °F). The driest month is February, with an average of 11.8 mm (0.46 in) of precipitation, while the wettest month is June, with an average of 77 mm (3.0 in). Annual precipitation is low, with an average of 392.5 mm (15.45 in). Its location in southwest Saskatchewan gives it slightly milder winters than the provincial capital, Regina, even though it is higher in elevation. Chinook winds happen several times a year allowing residents to enjoy unseasonably warm weather for short periods of time.

The highest temperature ever recorded in Swift Current was 41.7 °C (107 °F) on 12 July 1886.[28] The coldest temperature ever recorded was −47.8 °C (−54 °F) on 16 February 1936.[29]

| Climate data for Swift Current Airport, 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1885–present[f] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 17.2 (63.0) |

20.6 (69.1) |

22.2 (72.0) |

33.8 (92.8) |

37.3 (99.1) |

40.0 (104.0) |

41.7 (107.1) |

40.1 (104.2) |

36.5 (97.7) |

31.7 (89.1) |

25.0 (77.0) |

20.0 (68.0) |

41.7 (107.1) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | −5.9 (21.4) |

−4.3 (24.3) |

2.1 (35.8) |

10.9 (51.6) |

17.6 (63.7) |

21.3 (70.3) |

25.0 (77.0) |

25.2 (77.4) |

19.5 (67.1) |

10.8 (51.4) |

1.7 (35.1) |

−4.6 (23.7) |

9.9 (49.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −10.8 (12.6) |

−9.3 (15.3) |

−3.1 (26.4) |

4.5 (40.1) |

10.7 (51.3) |

15.2 (59.4) |

18.3 (64.9) |

18.0 (64.4) |

12.7 (54.9) |

4.9 (40.8) |

−3.2 (26.2) |

−9.3 (15.3) |

4.1 (39.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −15.7 (3.7) |

−14.2 (6.4) |

−8.4 (16.9) |

−1.9 (28.6) |

3.8 (38.8) |

9.1 (48.4) |

11.6 (52.9) |

10.8 (51.4) |

5.9 (42.6) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

−8.0 (17.6) |

−13.8 (7.2) |

−1.8 (28.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −45.0 (−49.0) |

−47.8 (−54.0) |

−36.1 (−33.0) |

−28.9 (−20.0) |

−12.2 (10.0) |

−3.3 (26.1) |

0.6 (33.1) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

−13.3 (8.1) |

−24.2 (−11.6) |

−35.0 (−31.0) |

−44.4 (−47.9) |

−47.8 (−54.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 16.1 (0.63) |

11.4 (0.45) |

16.2 (0.64) |

21.3 (0.84) |

45.3 (1.78) |

91.7 (3.61) |

46.2 (1.82) |

48.1 (1.89) |

40.6 (1.60) |

24.4 (0.96) |

17.9 (0.70) |

15.0 (0.59) |

394.2 (15.52) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 0.8 (0.03) |

1.0 (0.04) |

3.9 (0.15) |

15.4 (0.61) |

43.9 (1.73) |

81.5 (3.21) |

50.8 (2.00) |

47.6 (1.87) |

33.2 (1.31) |

14.3 (0.56) |

3.5 (0.14) |

0.9 (0.04) |

296.6 (11.68) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 15.6 (6.1) |

9.9 (3.9) |

14.5 (5.7) |

7.2 (2.8) |

2.7 (1.1) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

2.1 (0.8) |

6.1 (2.4) |

13.2 (5.2) |

16.9 (6.7) |

88.0 (34.6) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 98.4 | 122.7 | 166.4 | 230.1 | 275.6 | 299.8 | 340.4 | 301.1 | 202.5 | 175.6 | 110.4 | 83.9 | 2,406.9 |

| Percentage possible sunshine | 37.1 | 43.3 | 45.3 | 55.7 | 57.6 | 61.2 | 68.9 | 67.1 | 53.3 | 52.6 | 40.6 | 33.3 | 51.3 |

| Source: Environment Canada (sun 1981–2010)[30][31][32][33][34][35] | |||||||||||||

Transit

[edit]Swift Transit provides transit service in the city of Swift Current. The Saskatchewan Abilities Council provides both bus and paratransit (called Access Transit) to Swift Current and Yorkton.[36][37][38]

Service began in April 2015, replacing the Swift Current Tele-Bus. The Red line provides core service, running Monday to Saturday, from 7 am to 7 pm; starting the last run at 6pm. The Blue line, which started in 2017, runs Monday to Friday, from 8:45 am to 3 pm. No service is offered Sundays or holidays.[39] Swift Transit also runs three high school routes, as well as accommodating students from the downtown area on the Red line.[40][38]

The stop downtown at 41 Chaplin Street E, serves as the main transfer point between the lines, with the Red line servicing it twice on its route; and a second transfer point at the Swift Current Mall.[41][42]

Swift Current purchased three new Arboc buses which arrived in 2021, enhancing both regular and Access Transit services.[43]

Arts and culture

[edit]

The city is home to the Swift Current Museum, the Art Gallery of Swift Current, the Lyric Theatre and the Swift Current Library. The city is also host to the Windscape Kite Festival, which is the largest festival of its kind in Western Canada. A group of local talent started up a movie company called Dead Prairies and their first feature-length film Zombageddon was filmed in Swift Current. Zombageddon premiered at the Living Sky Casino on October 31, 2012 and made over $4,000 for the Swift Current SPCA.

In 2016, Swift Current became the first city in Saskatchewan to install a permanent rainbow crosswalk.[44]

Notable people

[edit]- Jeff Buchanan - hockey player

- Steve Buzinski - hockey player

- Reggie Cleveland - former Major League Baseball pitcher

- Brandin Cote - hockey player

- Lorna Crozier - poet

- Ken Epp - politician

- Nancy Heppner - politician

- Bill Hogaboam - hockey player

- Eric Malling - journalist, former host of CBC's The Fifth Estate and CTV's W5

- Patrick Marleau - ice hockey player for the San Jose Sharks, holds the NHL record for most games played.

- Trent McCleary - hockey player

- Travis Moen - ice hockey player for Montreal Canadiens, Anaheim Mighty Ducks, Dallas Stars, San Jose Sharks, Chicago Blackhawks. Stanley Cup Champion

- Caia Morstad - volleyball player

- Scotty Munro – ice hockey coach

- Darcy Regier - hockey executive

- Kelly Schafer - curler

- Darrel Scoville - hockey player

- Claire Drainie Taylor - actor

- Jeff Toms - hockey player

- Fred Wah - poet

- Brad Wall - former Premier of Saskatchewan

- Colter Wall - musician

- Dorothy Walton - badminton player

- Jack Wiebe - politician

Sports and recreation

[edit]Swift Current is home to the Swift Current Broncos, a hockey team that plays in the Western Hockey League. They play in the 2,879 seat Credit Union iPlex in the east end of town. The team has developed a number of NHL players such as Dave "Tiger" Williams, Joe Sakic, and Bryan Trottier. The Credit Union iPlex is also the home of the Swift Current Rampage a junior box lacrosse team along with SaskTel Curling Stadium Swift Current, opening inside the Swift Current Curling Club in 2021, offering live broadcasts from all games played.[45]

Swift Current hosted the 2016 World Women's Curling Championship.[46]

Swift Current is also home to the Swift Current 57's, a baseball team that plays in Canada's premier summer collegiate level baseball league called the Western Canadian Baseball League (WCBL). Former Major League Baseball players Reggie Cleveland (Boston Red Sox), Jim Dedrick (Baltimore Orioles) and Shawn Wooten (Anaheim Angels) all played for Swift Current before being drafted into professional baseball. Since 1992, Swift Current has won an unprecedented 11 league championships (1992, 1994, 1996, 1997, 1998, 2000, 2001, 2005, 2006, 2010, and 2016). The 57's play at Mitchell Field, located just north of the Iplex.

Other sports institutions in the city include:

- Speedy Creek Racing Club

- Chinook Golf Course

- Elmwood Golf Course

Lake Diefenbaker and Saskatchewan Landing Provincial Park are 50 km (31 mi) north of the city on Highway 4. The park provides recreational activities like fishing, swimming, boating, camping, hiking and 4 RV parks.

Swift Current Motorcross Club has a track on the west side of town, just off 11th Ave NW.

Swift Current is also home to Canadian professional track and field/cross-country athlete Kelly Wiebe.

Government

[edit]Swift Current has had its own Saskatchewan Legislature district since 1908. The current incarnation of Swift Current (provincial electoral district) is nearly coterminous with Swift Current's city limits, excluding only an industrial park on the western side of the Trans-Canada Highway.[47] In the House of Commons, Swift Current is part of Cypress Hills—Grasslands, whose boundaries extend to Caronport and Kindersley.[48] Following the 2021 federal election the riding is represented by Jeremy Patzer, MP and from 2018 provincially by Everett Hindley, MLA.[49][50]

At both higher levels of government, Swift Current is predominantly conservative. The city was the home constituency of the first Saskatchewan Party premier, Brad Wall, who won more than 80% of the popular vote on two occasions.[51][52] Federally, its last non-conservative MP was Irvin Studer, a Liberal who represented Swift Current—Maple Creek from 1953 to 1958.[53]

The city's current mayor is Al Bridal, who defeated incumbent Denis Perrault in the 2020 Saskatchewan municipal elections. On the same ballot, two of five incumbent councillors held their seats. After 40 centimetres of snow fell on election day, voting in the city was postponed by two days.[54][55]

Media

[edit]- Southwest Booster

- Prairie Post

- Radio

- AM 540 - CBK, CBC Radio One, Canadian Broadcasting Corporation

- AM 570 - CKSW, country music, Golden West Broadcasting

- FM 94.1 - CIMG-FM, "The Eagle 94 One" classic hits, Golden West Broadcasting

- FM 95.7 - CBK-FM-4, CBC Radio 2, Canadian Broadcasting Corporation

- FM 97.1 - CKFI-FM, "Magic 97" adult contemporary, Golden West Broadcasting

- Television

- Channel 12 - CKMC-TV, CTV (analogue repeater of CKCK-DT Regina)

- Southwest TV News is an internet-based news program focused on Swift Current and area. It is sometimes broadcast on Citytv Saskatchewan.

Swift Current was previously served by CJFB-TV channel 5, a private CBC Television outlet; this station would close down in 2002, with its transmitter becoming CBKT-4, a repeater of CBKT Regina. CBKT-4 would close down on July 31, 2012, due to budget cuts handed down by the CBC.[56][57]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Statistic includes all persons that did not make up part of a visible minority or an indigenous identity.

- ^ Statistic includes total responses of "Filipino" and "Southeast Asian" under visible minority section on census.

- ^ Statistic includes total responses of "Chinese", "Korean", and "Japanese" under visible minority section on census.

- ^ Statistic includes total responses of "West Asian" and "Arab" under visible minority section on census.

- ^ Statistic includes total responses of "Visible minority, n.i.e." and "Multiple visible minorities" under visible minority section on census.

- ^ Climate data was recorded in the city of Swift Current from December 1885 to July 1938 and at Swift Current Airport from May 1938 to present.

Citations

[edit]- ^ "Saskatchewan slang". canada.com. Postmedia Network Inc. November 7, 2007. Archived from the original on November 9, 2012. Retrieved December 21, 2013.

- ^ "2021 Census of Population Swift Current". Statistics Canada. Retrieved 11 February 2023.

- ^ a b Census Profile, 2016 Census

- ^ "Swift Current Population 2024". worldpopulationreview.com. Retrieved 23 January 2024.

- ^ "2021 Census of Population Swift Current". Statistics Canada. Retrieved 11 February 2023.

- ^ Tourism Swift Current

- ^ McGowan, Don C. The Green and Growing Years: Swift Current, 1907-1914. Victoria: Cactus Publications, 1982.

- ^ "History of Swift Current". City of Swift Current. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- ^ "Natural Resources". Grow with Swift Current. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- ^ McGowan, Don C. Grassland Settlers: The Swift Current Region During the Era of the Ranching Frontier. Regina: Canadian Plains Research Centre, University of Regina, 1975.

- ^ "Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada - The Directory of Designated Heritage Railway Stations in Saskatchewan". Parks Canada. Archived from the original on October 8, 2012. Retrieved February 7, 2011.

- ^ "Table 5: Population of urban centres, 1916-1946, with guide to locations". Census of the Prairie Provinces, 1946. Vol. I: Population. Ottawa: Dominion Bureau of Statistics. 1949. pp. 397–400.

- ^ "Table 6: Population by sex, for census subdivisions, 1956 and 1951". Census of Canada, 1956. Vol. I: Population. Ottawa: Dominion Bureau of Statistics. 1958.

- ^ "Table 9: Population by census subdivisions, 1966 by sex, and 1961". 1966 Census of Canada. Western Provinces. Vol. Population: Divisions and Subdivisions. Ottawa: Dominion Bureau of Statistics. 1967.

- ^ "Table 3: Population for census divisions and subdivisions, 1971 and 1976". 1976 Census of Canada. Census Divisions and Subdivisions, Western Provinces and the Territories. Vol. Population: Geographic Distributions. Ottawa: Statistics Canada. 1977.

- ^ "Table 2: Census Subdivisions in Alphabetical Order, Showing Population Rank, Canada, 1981". 1981 Census of Canada. Vol. Census subdivisions in decreasing population order. Ottawa: Statistics Canada. 1982. ISBN 0-660-51563-6.

- ^ "Table 2: Population and Dwelling Counts, for Census Divisions and Census Subdivisions, 1986 and 1991 – 100% Data". 91 Census. Vol. Population and Dwelling Counts – Census Divisions and Census Subdivisions. Ottawa: Statistics Canada. 1992. pp. 100–108. ISBN 0-660-57115-3.

- ^ "Population and Dwelling Counts, for Canada, Provinces and Territories, and Census Divisions, 2001 and 1996 Censuses – 100% Data (Saskatchewan)". Statistics Canada. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

- ^ "Population and dwelling counts, for Canada, provinces and territories, and census subdivisions (municipalities), 2006 and 2001 censuses – 100% data (Saskatchewan)". Statistics Canada. 6 January 2010. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

- ^ "About Us | Swift Current". www.swiftcurrent.ca. Retrieved 16 February 2023.

- ^ "Population and dwelling counts: Canada, provinces and territories, census divisions and census subdivisions (municipalities), Saskatchewan". Statistics Canada. 9 February 2022. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- ^ "2011 Community Profiles". 2011 Canadian census. Statistics Canada. 21 March 2019. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (26 October 2022). "Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (27 October 2021). "Census Profile, 2016 Census". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (27 November 2015). "NHS Profile". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (20 August 2019). "2006 Community Profiles". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (2 July 2019). "2001 Community Profiles". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ "July 1886". Environment Canada. 22 September 2015. Retrieved 25 June 2016.

- ^ "February 1936". Environment Canada. 22 September 2015. Retrieved 25 June 2016.

- ^ Environment Canada—Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010, accessed February 20, 2016.

- ^ "1991–2020 normals". Environment Canada. 30 January 2024. Retrieved 17 April 2024.

- ^ "Swift Current". Environment Canada. 22 September 2015. Retrieved 25 June 2016.

- ^ "Swift Current CDA". Environment Canada. 31 October 2011. Retrieved 12 August 2018.

- ^ "Daily Data Report for September 2022". Canadian Climate Data. Environment and Climate Change Canada. Retrieved 17 April 2024.

- ^ "Daily Data Report for January 2024, Swift Current". Environment and Climate Change Canada. Retrieved 17 April 2024.

- ^ "Access Transit - SaskAbilities". Retrieved 23 December 2022.

- ^ "Year in Review 2015: Abilities Council Taking Over City Transit Operations". SwiftCurrentOnline. Retrieved 24 December 2022.

- ^ a b "City's Transit Operational Contract Renewed". SwiftCurrentOnline. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ "Swift Transit - The RED & BLUE LINES | Swift Current". www.swiftcurrent.ca. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ "Swift Transit | High School Routes" (PDF).

- ^ "Swift Transit | Dec 2022 Map".

- ^ "Swift Transit | Swift Current". www.swiftcurrent.ca. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ "New Buses Expand Ride Options for Those Experiencing Disability". SwiftCurrentOnline. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ "1st Saskatchewan rainbow crosswalk installed in Swift Current | CBC News".

- ^ "SaskTel Powers Curling Stadium Swift Current". 7 October 2021. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ^ "Visitor Guide". www.curling.ca. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ^ "Swift Current, 29th General Election" (PDF). Elections Saskatchewan. Retrieved 21 March 2021.

- ^ "Cypress Hills-Grasslands". Elections Canada. Retrieved 21 March 2021.

- ^ "Hon. Everett Hindley". Legislative Assembly of Saskatchewan. Retrieved 21 March 2021.

- ^ "Cypress Hills—Grasslands". Our Commons. Parliament of Canada. Retrieved 21 March 2021.

- ^ Boda, Michael (7 November 2011). Statement of Votes - Volume I (PDF). Regina: Elections Saskatchewan. p. 134. Retrieved 21 March 2021.

- ^ Boda, Michael (4 April 2016). Statement of Votes - Volume I (PDF). Regina: Elections Saskatchewan. p. 287. Retrieved 21 March 2021.

- ^ "Irvin William Studer, M.P." Parlinfo. Library of Parliament. Retrieved 21 March 2021.

- ^ Radford, Evan (13 November 2020). "Swift Current elects new mayor; to focus on smart spending, 'healthy discussion'". Regina Leader-Post. Retrieved 21 March 2021.

- ^ Zammit, David (12 November 2020). "Bridal Wins Swift Current Mayoral Race". Swift Current Online. Retrieved 21 March 2021.

- ^ "Speaking notes for Hubert T. Lacroix regarding measures announced in the context of the Deficit Reduction Action Plan". CBC Radio. 4 April 2012. Retrieved 19 April 2017.

- ^ "Broadcasting Decision CRTC 2012-384". Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission. 17 July 2012. Retrieved 19 April 2017.