Old Town, Warsaw

Old Town | |

|---|---|

Neighbourhood and City Information System area | |

| Stare Miasto | |

The Castle Square, located in Old Town, in 2018 | |

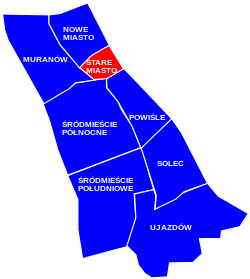

The location of the neighbourhood of Old Town in the district of Śródmieście, in accordance to the City Information System | |

| Coordinates: 52°14′59″N 21°0′44″E / 52.24972°N 21.01222°E | |

| Country | |

| Voivodeship | Masovian Voivodeship |

| City county | Warsaw |

| District | Śródmieście |

| Municipal neighbourhood | Staromiejskie |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Official name | Historic Centre of Warsaw |

| Criteria | Cultural: (ii), (vi) |

| Designated | 1980 Minor boundary modification inscribed year: 2014 |

| Reference no. | 30bis |

| UNESCO region | Europe |

| Area | 25.93 ha (64.1 acres) |

| Buffer zone | 666.78 ha (1,647.6 acres) |

Warsaw Old Town,[a] also known as Old Town,[b] and historically known as Old Warsaw,[c][1] is a neighbourhood, and an area of the City Information System, in the city of Warsaw, Poland, located within the district of Śródmieście.[2] It is the oldest portion of the city, and contains numerous historic buildings, mostly from 17th and 18th centuries, such as the Royal Castle, city walls, St. John's Cathedral, and the Barbican, the Old Town Market Square and the Warsaw Mermaid Statue[3][4].[1][5] The settlement itself dates back to between the 13th and 14th centuries, and was granted town privileges c. 1300.[1][6]

During World War II, the Old Town was nearly totally destroyed, and subsequently reconstructed. The project was the world's first attempt to resurrect an entire historic city core and was included on the UNESCO World Heritage list in 1980.[7][8] The reconstruction efforts were again recognized in 2011 when all its documents and records were added to UNESCO's Memory of the World Programme.[9]

History

[edit]

The Old Town was established in the 13th century. Initially surrounded by an earthwork rampart, prior to 1339 it was fortified with brick city walls. The town originally grew up around the castle of the Dukes of Mazovia that later became the Royal Castle. The Market Square (Rynek Starego Miasta) was laid out sometime in the late 13th or early 14th century, along the main road linking the castle with the New Town to the north.

Until 1817 the Old Town's most notable feature was the Town Hall built before 1429. In 1701 the square was rebuilt by Tylman Gamerski, and in 1817 the Town Hall was demolished. Since the 19th century, the four sides of the Market Square have borne the names of four notable Poles who once lived on the respective sides: Ignacy Zakrzewski (south), Hugo Kołłątaj (west), Jan Dekert (north) and Franciszek Barss (east).

In the early 1910s, Warsaw Old Town was the home of the prominent Yiddish writer Alter Kacyzne, who later depicted life there in his 1929 novel "שטאַרקע און שוואַכע" (Shtarke un Shvache, "The Strong and the Weak"). As depicted in the novel, the Old Town at that time was a slum neighborhood, with poor families—some Jewish, other Christian—living very crowded in subdivided tenements that had once been aristocrats' palaces. Parts of it were bohemian, with painters and artists having their studios, while some streets were a Red-light district housing brothels.

In 1918 the Royal Castle once again became the seat of Poland's highest authorities: the President of Poland and his chancellery. In the late 1930s, during the mayoralty of Stefan Starzyński, the municipal authorities began refurbishing the Old Town and restoring it to its former glory. The Barbican and the Old Town Market Place were partly restored. These efforts, however, were brought to an end by the outbreak of World War II.

During the Invasion of Poland (1939), much of the district was badly damaged by the German Luftwaffe, which targeted the city's residential areas and historic landmarks in a campaign of terror bombing.[11][12] Following the Siege of Warsaw, parts of the Old Town were rebuilt, but immediately after the Warsaw Uprising (August–October 1944) what had been left standing was systematically blown up by the German Army. A statue commemorating the Uprising, "the Little Insurgent," now stands on the Old Town's medieval city wall.[13]

After World War II, the Old Town was meticulously rebuilt.[12] In an effort at anastylosis, as many as possible of the original bricks were reused. However, the reconstruction was not always accurate to prewar Warsaw, sometimes deference being given to an earlier period, an attempt being made to improve on the original, or an authentic-looking facade being made to cover a more modern building.[14] The rubble was sifted for reusable decorative elements, which were reinserted into their original places. Bernardo Bellotto's 18th-century vedute, as well as pre-World War II architecture students' drawings, were used as essential sources in the reconstruction effort; however, Bellotto's drawings had not been entirely immune to artistic licence and embellishment, and in some cases this was transferred to the reconstructed buildings.

Squares

[edit]The Old Town Market Place (Rynek Starego Miasta), which dates back to the end of the 13th century, is the true heart of the Old Town, and until the end of the 18th century it was the heart of all of Warsaw.[15] Here the representatives of guilds and merchants met in the Town Hall (built before 1429, pulled down in 1817), and fairs and the occasional execution were held. The houses around it represented the Gothic style until the great fire of 1607, after which they were rebuilt in late-Renaissance style.[16]

Castle Square (plac Zamkowy) is a visitor's first view of the reconstructed Old Town, when approaching from the more modern center of Warsaw. It is an impressive sight, dominated by Sigismund's Column, which towers above the beautiful Old Town houses. Enclosed between the Old Town and the Royal Castle, Castle Square is steeped in history. Here was the gateway leading into the city called the Kraków Gate (Brama Krakowska).[17] It was developed in the 14th century and continued to be a defensive area for the kings. The square was in its glory in the 17th century when Warsaw became the country's capital and it was here in 1644 that King Władysław IV erected the column to glorify his father Sigismund III Vasa, who is best known for moving the capital of Poland from Kraków to Warsaw.[17] The Museum of Warsaw is also located there.

Canon Square (plac Kanonia), behind St. John's Cathedral, is a small triangular square.[18] Its name comes from the 17th-century tenement houses which belonged to the canons of the Warsaw chapter.[18] Some of these canons were quite famous, like Stanisław Staszic who was the co-author of the Constitution of 3 May 1791. Formerly, it was a parochial cemetery, of which there remains a Baroque figure of Our Lady from the 18th century.[18] In the middle of the square, is the bronze bell of Warsaw, that Grand Crown Treasurer Jan Mikołaj Daniłowicz, founded in 1646 for the Jesuit Church in Jarosław.[18] The bell was cast in 1646 by Daniel Tym—the designer of Sigismund's Column. Where the Canon Square meets the Royal Square is a covered passage built for Queen Anna Jagiellon in the late 16th century and extended in the 1620s after Michał Piekarski's failed 1620 attempt to assassinate King Sigismund III Vasa as he was entering the cathedral.[19] Also the narrowest house in Warsaw is located there.

Recognition

[edit]In 1980, Warsaw's Old Town was placed on the UNESCO's list of World Heritage Sites as "an outstanding example of a near-total reconstruction of a span of history covering the 13th to the 20th century.[12]

The site is also one of Poland's official national Historic Monuments (Pomnik historii), as designated 16 September 1994. Its listing is maintained by the National Heritage Board of Poland.

In 2011, the Archive of Warsaw Reconstruction Office was added to UNESCO’s Memory of the World Programme.[9]

Gallery

[edit]-

1:300 model of Warsaw Old Town in 2nd half of 18th century, in Museum of Warsaw

-

Palace Square

-

Warsaw old town wide (Rynek Starego Miasta)

-

Reconstructed townhouses

-

Road to the Old Town

-

Market Square

-

An alley

-

Medieval basements at the Museum of Warsaw

-

Historical houses around Castle Square

-

Old Town Market Place with tourists

-

Statue of the mermaid (Old Town)

-

Jan Kiliński monument

-

Warsaw Old Town surrounded by the old medieval defensive walls

-

Defensive walls and the Barbican

-

Old Town street

-

Old Town

-

St. John's Cathedral, 14th century[20]

-

Jesuit Church, 1609[20]

-

St. Martin's Church, 1353–1752[20]

-

Warsaw Barbican, 1548

-

Gunpowder Tower, after 1379

-

Defensive walls, detail

-

Szeroki Dunaj Street

-

Piwna Street

-

Queen Anna's corridor connecting the Royal Castle with the St. John's Cathedral, 16th century. King Sigismund III was attacked by an assassin in the corridor before attending mass.

-

Canonicity Square

-

St John Street

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Encyklopedia Warszawy. Warsaw: Polish Scientific Publishers PWN, 1994, p. 806. ISBN 83-01-08836-2.

- ^ "Obszary MSI. Dzielnica Śródmieście". zdm.waw.pl (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2023-06-01. Retrieved 2023-03-12.

- ^ "Syrenka Warszawska" (in Polish). 2023-04-15. Retrieved 2024-11-03.

- ^ "Stare Miasto w Warszawie – odkrywamy warszawską starówkę". www.suerteprzewodnicy.pl (in Polish). 2024-09-28. Retrieved 2024-11-03.

- ^ Jerzy Lileyko: Najcenniejsze Zabytki Warszawy. Warsaw: Krajowa Agencja Wydawnicza, 1989, p. 30–36. ISBN 83-03-02485-X.

- ^ Robert Krzysztofik: Lokacje miejskie na obszarze Polski. Dokumentacja geograficzno-historyczna, Katowice, 2007, p. 80-81.

- ^ Stuart Dowell (21 July 2023). "Monumental reconstruction of Warsaw's Old Town which was devastated by WWII completed 70 years ago". thefirstnews.com. Archived from the original on 22 July 2023. Retrieved 22 July 2023.

- ^ "Historic Centre of Warsaw". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 15 March 2017. Retrieved 22 July 2023.

- ^ a b "Archive of Warsaw Reconstruction Office". en.unesco.com. Retrieved 22 July 2023.

- ^ "Kamienica "Pod Okrętem"". ePrzewodnik / Perełki Warszawy on-line (in Polish). Archived from the original on 7 February 2006. Retrieved 16 March 2009.

- ^ "Historic Centre of Warsaw". whc.unesco.org. Archived from the original on 15 March 2017. Retrieved 18 August 2008.

- ^ a b c "Old Town". www.destinationwarsaw.com. Archived from the original on 3 February 2014. Retrieved 18 August 2008.

- ^ "Warsaw's Old Town". www.ilovepoland.co.uk. Archived from the original on 26 May 2013. Retrieved 18 August 2008.

- ^ 99% invisible episode 72

- ^ "The Old Town Market Square". eGuide / Treasures of Warsaw on-line. Archived from the original on 18 February 2006. Retrieved 8 July 2008.

- ^ Marek Lewandowski. "Rynek Starego Miasta". www.stare-miasto.com (in Polish). Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 8 July 2008.

- ^ a b "Plac zamkowy". zapiecek.com (in Polish). Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 1 July 2008.

- ^ a b c d "Canonicity". eGuide / Treasures of Warsaw on-line. Archived from the original on 18 February 2006. Retrieved 12 May 2009.

- ^ Stefan Kieniewicz, ed., Warszawa w latach 1526-1795 (Warsaw in 1526–1795), vol. II, Warsaw, 1984, ISBN 83-01-03323-1.

- ^ a b c "Kościoły w Warszawie - Stare Miasto" Archived 2023-03-21 at the Wayback Machine. List of churches located in the Old Town in Warsaw.

![St. John's Cathedral, 14th century[20]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/ed/Warszawa%2C_bazylika_archikatedralna_%C5%9Bw._Jana_Chrzciciela_w_Warszawie_DZolopa_2022-08-18_141753_1207.jpg/120px-Warszawa%2C_bazylika_archikatedralna_%C5%9Bw._Jana_Chrzciciela_w_Warszawie_DZolopa_2022-08-18_141753_1207.jpg)

![Jesuit Church, 1609[20]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/89/Ko%C5%9Bci%C3%B3%C5%82_Matki_Bo%C5%BCej_%C5%81askawej_w_Warszawie_2020.jpg/105px-Ko%C5%9Bci%C3%B3%C5%82_Matki_Bo%C5%BCej_%C5%81askawej_w_Warszawie_2020.jpg)

![St. Martin's Church, 1353–1752[20]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/13/Kosciol_sw_marcina_warszawa.jpg/135px-Kosciol_sw_marcina_warszawa.jpg)