Saint Paul, Minnesota

Saint Paul | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Nicknames: "the Capital City", "the Saintly City", "Twin Cities" (with Minneapolis), "Pig's Eye", "STP", "Last City of the East" | |

| Motto: The most livable city in America* | |

Interactive map of St. Paul | |

| Coordinates: 44°56′52″N 93°06′14″W / 44.94778°N 93.10389°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Minnesota |

| County | Ramsey |

| Incorporated | March 4, 1854 |

| Named for | St. Paul the Apostle |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor–council[1] |

| • Mayor | Melvin Carter (DFL) |

| • Body | Saint Paul City Council |

| Area | |

• City | 56.10 sq mi (145.31 km2) |

| • Land | 51.97 sq mi (134.61 km2) |

| • Water | 4.13 sq mi (10.70 km2) |

| Elevation | 824 ft (251 m) |

| Population | |

• City | 311,527 |

• Estimate (2022)[5] | 303,176 |

| • Rank | US: 67th MN: 2nd |

| • Density | 5,994.02/sq mi (2,314.32/km2) |

| • Metro | 3,693,729 (US: 16th) |

| • Demonym | Saint Paulite |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 55101–55131, 55133, 55144-55146, 55150, 55155, 55164, 55170 |

| Area code | 651 |

| FIPS code | 27-58000 |

| GNIS ID | 2396511[3] |

| Website | stpaul.gov |

| Current as of October 12, 2023 | |

Saint Paul (often abbreviated St. Paul) is the capital of the U.S. state of Minnesota and the county seat of Ramsey County.[6] Situated on high bluffs overlooking a bend in the Mississippi River, Saint Paul is a regional business hub and the center of Minnesota's government.[7][8] The Minnesota State Capitol and the state government offices all sit on a hill close to the city's downtown district. One of the oldest cities in Minnesota, Saint Paul has several historic neighborhoods and landmarks, such as the Summit Avenue Neighborhood, the James J. Hill House, and the Cathedral of Saint Paul.[9][10] Like the adjacent city of Minneapolis, Saint Paul is known for its cold, snowy winters and humid summers.

According to census estimates, in 2022 the city's population was 303,176, making it the 67th-most populous city in the United States, the 12th-most populous in the Midwest, and the second-most populous in Minnesota.[11][12] Most of the city lies east of the Mississippi River near its confluence with the Minnesota River. Minneapolis is mostly across the Mississippi River to the west. Together, they are known as the "Twin Cities" and make up the core of the Minneapolis–Saint Paul metropolitan area, the third most populous metropolitan area in the Midwest.[13]

The Legislative Assembly of the Minnesota Territory established the Town of Saint Paul as its capital near existing Dakota Sioux settlements in November 1849.[14] It remained a town until 1854. The Dakota name for where Saint Paul is situated is "Imnizaska" for the "white rock" bluffs along the river.[15] The city has three sports venues: Xcel Energy Center, home to the Minnesota Wild and the Minnesota Frost, CHS Field, home to the St. Paul Saints, and Allianz Field, home to Minnesota United.[16]

Saint Paul has a mayor–council government. The current mayor is Melvin Carter III, who was first elected in 2018.

History

[edit]

Burial mounds in present-day Indian Mounds Park suggest the area was inhabited by the Hopewell Native Americans about 2,000 years ago.[17][18] From the early 17th century to 1837, the Mdewakanton Dakota, a band of the Dakota people, lived near the mounds at the village of Kaposia and consider the area encompassing present-day Saint Paul Bdóte, the site of creation for their people.[17][19] The Dakota called the area Imniza-Ska ("white cliffs") for its exposed white sandstone cliffs on the river's eastern side.[20][21] The Imniza-Ska were full of caves that were useful to the Dakota. The explorer Jonathan Carver documented the historic Wakan Tipi in the bluff below the burial mounds in 1767. In the Menominee language Saint Paul was called Sāēnepān-Menīkān, which means "ribbon, silk or satin village", suggesting its role in trade throughout the region after the introduction of European goods.[22]

After the 1803 Louisiana Purchase, U.S. Army Lieutenant Zebulon Pike negotiated approximately 100,000 acres (40,000 ha; 160 sq mi) of land from the indigenous Dakota in 1805 to establish a fort. A military reservation was intended for the confluence of the Mississippi and Minnesota rivers on both sides of the Mississippi up to Saint Anthony Falls. All of what is now the Highland Park neighborhood was included in this. Pike planned a second military reservation at the confluence of the St. Croix and Mississippi rivers.[23] In 1819, Fort Snelling was built at the Minnesota and Mississippi confluence. The 1837 Treaty with the Sioux ceded all tribal lands east of the Mississippi to the U.S. government.[24] Chief Little Crow III moved his village, Kaposia, from south of Mounds Park across the river a few miles onto Dakota land.[25][26] Fur traders, explorers, and settlers came to the area for the fort's security. Many were French-Canadians who predated American pioneers by some time. A whiskey trade flourished among the squatters and the fort's commander evicted them all from the fort's reservation. Fur trader turned bootlegger "Pig's Eye" Parrant, who set up business just outside the reservation, particularly irritated the commander.[27][21] By the early 1840s, a community had developed nearby that locals called Pig's Eye (French: L'Œil du Cochon) or Pig's Eye Landing after Parrant's popular tavern.[27] In 1842, a raiding party of Ojibwe attacked the Kaposia encampment south of Saint Paul. A battle ensued where a creek drained into wetlands two miles south of Wakan Tipi.[28] The creek was thereafter called Battle Creek and is today parkland. In the 1840s-70s the Métis brought their oxen and Red River Carts down Kellogg Street to Lambert's landing to send buffalo hides to market from the Red River of the North. Saint Paul was the southern terminus of the Red River Trails. In 1840, Pierre Bottineau became a prominent resident with a claim near the settlement's center.[29]

In 1841, Catholic missionary Lucien Galtier was sent to minister to the French Canadians at Mendota. He had a chapel he named for St. Paul built on the bluff above the riverboat landing downriver from Fort Snelling.[30][31] Galtier informed the settlers that they were to adopt the chapel's name for the settlement and cease the use of "Pig's Eye".[27] In 1847, New York educator Harriet Bishop moved to the settlement and opened the city's first school.[32] The Minnesota Territory was created in 1849 with Saint Paul as the capital. The U.S. Army made the territory's first improved road, Point Douglas Fort Ripley Military Road, in 1850. It passed through what became Saint Paul neighborhoods.[33] In 1857, the territorial legislature voted to move the capital to Saint Peter, but Joe Rolette, a territorial legislator, stole the text of the bill and went into hiding, preventing the move.[34]

The year 1858 saw more than 1,000 steamboats service Saint Paul,[32] making it a gateway for settlers to the Minnesota frontier or Dakota Territory. Geography was a primary reason the city became a transportation hub. The location was the last good point to land riverboats coming upriver due to the river valley's topography. For a time, Saint Paul was called "The Last City of the East."[35] Fort Snelling was important to Saint Paul from the start. Direct access from Saint Paul did not happen until the 7th bridge was built in 1880. Before that, there was a cable ferry crossing dating to at latest the 1840s. Once streetcars appeared, a new bridge to Saint Paul was built in 1904. Until the town built its first jail the fort's brig served Saint Paul. Industrialist James J. Hill founded his railroad empire in Saint Paul. The Great Northern Railway and the Northern Pacific Railway were both headquartered in Saint Paul until they merged with the Burlington Northern. Today they are part of the BNSF Railway.[35]

On August 20, 1904, severe thunderstorms and tornadoes damaged hundreds of downtown buildings, causing $1.78 million ($60.36 million today) in damages and ripping spans from the High Bridge.[36] During the 1960s, in conjunction with urban renewal, Saint Paul razed neighborhoods west of downtown for the creation of the interstate freeway system.[37] From 1959 to 1961, the Rondo neighborhood was demolished for the construction of Interstate 94. The loss of that African American enclave brought attention to racial segregation and unequal housing in northern cities.[38] The annual Rondo Days celebration commemorates the African American community.[39]

Downtown Saint Paul had skyscraper-building booms beginning in the 1970s. Because the city center is directly beneath the flight path into the airport across the river there is a height restriction for all construction. The tallest buildings, such as Galtier Plaza (Jackson and Sibley Towers), The Pointe of Saint Paul condominiums, and the city's tallest building, Wells Fargo Place (formerly Minnesota World Trade Center), were constructed in the late 1980s.[40] In the 1990s and 2000s, the tradition of bringing new immigrant groups to the city continued. As of 2004, nearly 10% of the city's population were recent Hmong immigrants from Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Thailand, and Myanmar.[41] Saint Paul is the location of the Hmong Archives.[42]

Geography

[edit]

Saint Paul's history and growth as a landing port are tied to water. The city's defining physical characteristic, the confluence of the Mississippi and Minnesota Rivers, was carved into the region during the last ice age, as were the steep river bluffs and dramatic palisades on which the city is built. Receding glaciers and Lake Agassiz forced torrents of water from a glacial river that served the river valleys.[43] The city is situated in east-central Minnesota.

The Mississippi River forms a municipal boundary on part of the city's west, southwest, and southeast sides. Minneapolis, the state's largest city, lies to the west. Falcon Heights, Lauderdale, Roseville, and Maplewood are north, with Maplewood lying to the east. The cities of West Saint Paul and South Saint Paul are to the south, as are Lilydale, Mendota, and Mendota Heights, across the river from the city. The city's largest lakes are Pig's Eye Lake, which is part of the Mississippi, Lake Phalen, and Lake Como. According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has an area of 56.18 square miles (145.51 km2), of which 51.98 square miles (134.63 km2) is land and 4.20 square miles (10.88 km2) is water.[44]

The Parks and Recreation department is responsible for 160 parks and 41 recreation centers.[45] The city ranked #2 in park access and quality, after only Minneapolis, in the 2018 ParkScore ranking of the top 100 park systems across the United States according to the nonprofit Trust for Public Land.[46]

Neighborhoods

[edit]Saint Paul's Department of Planning and Economic Development divides Saint Paul into 17 Planning Districts, created in 1979 to allow neighborhoods to participate in governance and use Community Development Block Grants. With a funding agreement directly from the city, the councils share a pool of funds.[47] The councils have significant land-use control, a voice in guiding development, and they organize residents.[48] The planning districts mostly represent traditional neighborhoods and combinations of smaller neighborhoods within the city.

The city's 17 Planning Districts are:

Climate

[edit]

Saint Paul has a humid continental climate typical of the Upper Midwestern United States. Winters are frigid and snowy, while summers are warm to hot and humid. On the Köppen climate classification, Saint Paul falls in the hot summer humid continental climate zone (Dfa). The city experiences a full range of precipitation and related weather events, including snow, sleet, ice, rain, thunderstorms, tornadoes, and fog.[49]

Due to its northerly location and lack of large bodies of water to moderate the air, Saint Paul is sometimes subjected to cold Arctic air masses, especially during late December, January, and February. The average annual temperature of 46.5 °F (8.1 °C) gives the Minneapolis−Saint Paul metropolitan area the coldest annual mean temperature of any major metropolitan area in the continental U.S.[50]

Saint Paul is expected to be affected by climate change. More extreme heat waves are expected, as is increased precipitation in the spring and summer, which could cause river and flash flooding. Vector-borne transmission of such diseases as West Nile Virus, Lyme disease, and human anaplasmosis may increase because of changes in temperature and precipitation patterns.[51]

| Climate data for St. Paul Downtown Airport, Minnesota (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1872–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 58 (14) |

64 (18) |

83 (28) |

93 (34) |

99 (37) |

101 (38) |

104 (40) |

104 (40) |

101 (38) |

90 (32) |

78 (26) |

63 (17) |

104 (40) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 23.9 (−4.5) |

28.7 (−1.8) |

41.7 (5.4) |

56.8 (13.8) |

68.9 (20.5) |

78.5 (25.8) |

82.6 (28.1) |

80.4 (26.9) |

72.4 (22.4) |

58.0 (14.4) |

42.1 (5.6) |

28.6 (−1.9) |

55.2 (12.9) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 16.3 (−8.7) |

20.8 (−6.2) |

33.1 (0.6) |

47.0 (8.3) |

58.9 (14.9) |

68.8 (20.4) |

73.3 (22.9) |

71.1 (21.7) |

62.9 (17.2) |

49.0 (9.4) |

34.6 (1.4) |

21.7 (−5.7) |

46.5 (8.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 8.6 (−13.0) |

12.9 (−10.6) |

24.6 (−4.1) |

37.2 (2.9) |

48.9 (9.4) |

59.2 (15.1) |

64.0 (17.8) |

61.7 (16.5) |

53.4 (11.9) |

40.0 (4.4) |

27.1 (−2.7) |

14.8 (−9.6) |

37.7 (3.2) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −41 (−41) |

−33 (−36) |

−26 (−32) |

6 (−14) |

23 (−5) |

34 (1) |

45 (7) |

39 (4) |

28 (−2) |

8 (−13) |

−25 (−32) |

−39 (−39) |

−41 (−41) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.48 (12) |

0.52 (13) |

1.43 (36) |

2.58 (66) |

3.97 (101) |

4.63 (118) |

3.97 (101) |

4.10 (104) |

3.08 (78) |

2.47 (63) |

1.32 (34) |

0.65 (17) |

29.20 (742) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 4.0 | 4.3 | 7.1 | 10.6 | 12.7 | 13.0 | 9.9 | 10.0 | 9.6 | 9.2 | 6.2 | 4.9 | 101.5 |

| Source 1: NOAA[52][53] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: The Weather Channel[54] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 1,112 | — | |

| 1860 | 10,401 | 835.3% | |

| 1870 | 20,030 | 92.6% | |

| 1880 | 41,473 | 107.1% | |

| 1890 | 133,156 | 221.1% | |

| 1900 | 163,065 | 22.5% | |

| 1910 | 214,744 | 31.7% | |

| 1920 | 234,698 | 9.3% | |

| 1930 | 271,606 | 15.7% | |

| 1940 | 287,736 | 5.9% | |

| 1950 | 311,349 | 8.2% | |

| 1960 | 313,411 | 0.7% | |

| 1970 | 309,980 | −1.1% | |

| 1980 | 270,230 | −12.8% | |

| 1990 | 272,235 | 0.7% | |

| 2000 | 287,151 | 5.5% | |

| 2010 | 285,068 | −0.7% | |

| 2020 | 311,527 | 9.3% | |

| 2023 (est.) | 303,820 | [5] | −2.5% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[55] 2020 Census[4] | |||

| Demographic profile | 2020[56] | 2010[57] | 2000[58] | 1990[59] | 1970[59] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (non-Hispanic) | 48.8% | 55.9% | 64.0% | 80.4% | 93.6%[60] |

| Asian (non-Hispanic) | 19.2% | 14.9% | 12.4% | 7.1% | 0.2% |

| Black or African American (non-Hispanic) | 16.5% | 15.3% | 11.7% | 7.4% | 3.5% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 9.7% | 9.6% | 7.9% | 4.2% | 2.1%[60] |

2020 census

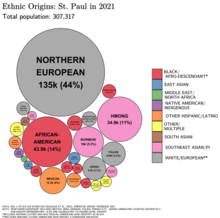

[edit]As of the census of 2020,[61] the population was 311,527. The population density was 5,994.0 inhabitants per square mile (2,314.3/km2). There were 127,392 housing units at an average density of 2,451.1 per square mile (946.4/km2). In terms of race, the city's population was 50.5% White (21.1% German), 19.2% Asian (10.9% Hmong, 2.53% Burmese, 0.85% Vietnamese, 0.69% Chinese, 0.51% Indian), 16.8% Black or African American (1.7% Somali, 1.5% Ethiopian), 1.0% Native American, 4.8% from other races, and 7.6% from two or more races. Residents of Hispanic or Latino ancestry, of any race, made up 9.7% of the population (6.58% Mexican, 0.68% Salvadoran).[62]

The 2020 census of the city included 291 people incarcerated in adult correctional facilities and 5,640 people in student housing.[63]

According to the American Community Survey estimates for 2016–2020, the median income for a household in the city was $59,717, and the median income for a family was $74,852. Male full-time workers had a median income of $50,186 versus $45,541 for female workers. The per capita income was $32,779. About 13.2% of families and 17.9% of the population were below the poverty line, including 27.0% of those under age 18 and 10.1% of those age 65 or over.[64] Of the population age 25 and over, 87.6% were high school graduates or higher and 41.3% had a bachelor's degree or higher.[65]

2010 census

[edit]As of the 2010 census,[66] there were 285,068 people, 111,001 households, and 59,689 families residing in the city. The population density was 5,484.2 inhabitants per square mile (2,117.5/km2). There were 120,795 housing units at an average density of 2,323.9 per square mile (897.3/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 60.1% white, 15.7% African American, 1.1% Native American, 15.0% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 3.9% from other races, and 4.2% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino people of any race were 9.6% of the population.

There were 111,001 households, of which 30.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 34.1% were married couples living together, 14.8% had a female householder with no husband present, 4.9% had a male householder with no wife present, and 46.2% were non-families. 35.8% of all households were made up of individuals, and 8.5% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.47 and the average family size was 3.33.

The median age in the city was 30.9 years. 25.1% of residents were under the age of 18; 13.9% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 29.6% were from 25 to 44; 22.6% were from 45 to 64; and 9% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 48.9% male and 51.1% female.

Ethnic history

[edit]The earliest known inhabitants of the St. Paul area, from about 400 AD, were members of the Hopewell tradition, who buried their dead in mounds on the river bluffs (now Indian Mounds Park). The next known inhabitants were the Mdewakanton Dakota in the 17th century, who fled their ancestral home of Mille Lacs Lake in central Minnesota in response to westward expansion of the Ojibwe nation.[19] The Ojibwe later occupied the north (east) bank of the Mississippi River.

By 1800, French-Canadian explorers came through the region and attracted fur traders. Fort Snelling and Pig's Eye Tavern also brought the first Yankees from New England and English, Irish, and Scottish immigrants, who had enlisted in the army and settled nearby after discharge. These early settlers and entrepreneurs built houses on the heights north of the river. The first wave of immigration came with the Irish, who settled at Connemara Patch along the Mississippi, named for their home, Connemara, Ireland. The Irish became prolific in politics, city governance, and public safety, much to the chagrin of the Germans and French, who had grown into the majority. In 1850, the first of many groups of Swedish immigrants passed through St. Paul on their way to farming communities in northern and western regions of the territory. A large group settled in Swede Hollow, which later became home to Poles, Italians, and Mexicans. The last Swedish presence moved up St. Paul's East Side along Payne Avenue in the 1950s.[67]

Of people who specified European ancestry in the 2005–07 American Community Survey of St. Paul, 26.4% were German, 13.8% Irish, 8.4% Norwegian, 7.0% Swedish, and 6.2% English. There is also a visible community of people of Sub-Saharan African ancestry, representing 4.2% of the population.

By the 1980s, the Thomas-Dale area, once an Austro-Hungarian enclave known as Frogtown (German: Froschburg), became home to Vietnamese and other Southeast Asian people who had left their war-torn countries. A settlement program for the Hmong diaspora came soon after, and by 2000, St. Paul had the largest urban Hmong contingent in the nation.[68][69][70]

Hmong Americans make up 11% of St. Paul's population as of 2021, and Saint Paul, as well as the Twin Cities area in general, is considered the center of Hmong culture in America. Hmongs are most concentrated in the neighborhoods of Frogtown, Payne-Phalen, Dayton's Bluff, the North End, and the Greater East Side,[62] which are considered ethnic enclaves for Hmong Minnesotans, with a large number of businesses, organizations, and events catering to the Hmong population, such as the Hmongtown Marketplace in Frogtown.

Other large Southeast Asian populations live in Saint Paul, particularly Burmese Americans of the Karen and Karenni ethnic group, who immigrated to the U.S. as refugees in the 2000s and 2010s due to internal conflict and discrimination in Myanmar. Minnesota is believed to have the largest population of Karen Americans, with a population of 12,000 in 2017,[71] who are mostly concentrated in Saint Paul. Burmese and Karen residents of Saint Paul make up 5.2% of the population in 2021, and are most concentrated in the neighborhoods of the North End, Payne-Phalen, and Frogtown.[62]

Mexican immigrants have settled in St. Paul since the 1930s; although Mexican populations exist throughout Saint Paul, by far the largest concentration of Mexican Americans is on St. Paul's West Side, where Mexicans form a plurality of the population; Mexico opened a foreign consulate there in 2005.[72][73] Saint Paul also has a large population of Central Americans, particularly Salvadorans, throughout eastern St. Paul and the West Side.

St. Paul has become home to a large number of Somalis and Ethiopians since the 1990s, largely as refugees fleeing conflict in their home regions. Somali and Ethiopian populations are largest in the neighborhoods of Summit-University and Frogtown, where there are many businesses and organizations for Somali and Ethiopian populations.[62]

African Americans in St. Paul initially entered through servitude to officers at Fort Snelling, marking a crucial point in their history. Despite the absence of legal slavery in Minnesota, Army officers were permitted to bring their enslaved individuals into the region.[74] Today, African Americans are one of the largest groups among Saint Paul's population; African Americans make up approximately 14% of Saint Paul's population, the second-largest background group, before Hmongs and after German-Americans. The city's African American residents are concentrated in its central and eastern neighborhoods.

Most St. Paul residents claiming religious affiliation are Christian, split between the Roman Catholic Church and various Protestant denominations. The Roman Catholic presence comes from Irish, German, Scottish, and French Canadian settlers, later bolstered by Hispanic immigrants. There are Jewish synagogues such as Mount Zion Temple and significant populations of Hindus, Muslims, and Buddhists.[75] The city has been dubbed "paganistan" due to its large Wiccan population.[76]

Economy

[edit]

The Minneapolis–Saint Paul–Bloomington area employs 1,570,700 people in the private sector as of July 2008, 82.43% of whom work in private service providing-related jobs.[77]

Major corporations headquartered in Saint Paul include Ecolab, a chemical and cleaning product company[78] that the Minneapolis/St. Paul Business Journal named in 2008 as the eighth-best place to work in the Twin Cites for companies with 1,000 full-time Minnesota employees,[79] and Securian Financial Group Inc.[80]

The 3M Company moved to St. Paul in 1910. It built an art deco headquarters at 900 Bush that still stands. Headquarters operations moved to the Maplewood campus in 1964. 3M manufacturing continued for a couple more decades until all St. Paul operations ceased.

The city was home to the Ford Motor Company's Twin Cities Assembly Plant, which opened in 1924 and closed at the end of 2011. The plant was in Highland Park on the Mississippi River, adjacent to Lock and Dam No. 1, Mississippi River, which generates hydroelectric power.[81] The site is being redeveloped into a mixed-used area called Highland Bridge which, when complete, will include 3,800 housing units, most opening in 2023.[82]

Saint Paul has financed city development with tax increment financing (TIF). In 2018, it had 55 TIF districts. Projects that have benefited from TIF funding include the St. Paul Saints stadium, and the affordable housing along the Twin Cities Metro Green Line.[83]

Housing

[edit]In November 2021, Saint Paul became the only Midwestern city to regulate rent increases when voters passed a rent control ordinance as part of a larger effort to curb rising housing costs.[84][85] The law limited annual rent increases to three percent and prohibited higher increases after a tenant vacated a unit.[85] In September 2022, the Saint Paul City Council voted to amend the law, allowing higher vacancy increases and exempting units built in the preceding or following 20 years from the increase cap.[86][87]

Culture

[edit]

Every January, Saint Paul hosts the Saint Paul Winter Carnival, a tradition that began in 1886 when a New York reporter called Saint Paul "another Siberia". The organizers had a model in the Montreal Winter Carnival the year before. Architect A. C. Hutchinson designed the Montreal ice castle and was hired to design St. Paul's first.[88] The event has now been held 135 times with an attendance of 350,000. It includes an ice sculpting competition, a snow sculpting competition, a medallion treasure hunt, food, activities, and an ice palace when it can be arranged.[89] The Como Zoo and Conservatory and adjoining Japanese Garden are popular year-round. The historic Landmark Center in downtown Saint Paul hosts cultural and arts organizations. The city's recreation sites include Indian Mounds Park, Battle Creek Regional Park, Harriet Island Regional Park, Highland Park, the Wabasha Street Caves, Lake Como, Lake Phalen, and Rice Park, as well as several areas abutting the Mississippi River. The Irish Fair of Minnesota is held annually at the Harriet Island Pavilion area. The country's largest Hmong American sports festival, the Freedom Festival, is held the first weekend of July at McMurray Field near Como Park.

The city is associated with the Minnesota State Fair in neighboring Falcon Heights just west of Como Park. The fair dates to before statehood. With the competing interests of Minneapolis and St. Paul, it was held on "neutral ground" between both. That area refused to become part of St. Paul or Roseville and became Falcon Heights in the 1950s. The University of Minnesota Saint Paul Campus is actually in Falcon Heights.

Fort Snelling is often identified as being in St. Paul but is actually its own unorganized territory. The eastern part of Fort Snelling Unorganized Territory (MSP included) has a St. Paul mailing address. The western side has a Minneapolis ZIP code.

Saint Paul is the birthplace of cartoonist Charles M. Schulz, who lived in Merriam Park from infancy until 1960.[90] Schulz's Peanuts inspired giant, decorated sculptures around the city, a Chamber of Commerce promotion in the late 1990s.[91] Other notable residents include writer F. Scott Fitzgerald and playwright August Wilson, who premiered many of the ten plays in his Pittsburgh Cycle at the local Penumbra Theater.[92]

The Ordway Center for the Performing Arts hosts theater productions and the Minnesota Opera is a founding tenant.[93] RiverCentre, attached to Xcel Energy Center, serves as the city's convention center. The city has contributed to the music of Minnesota and the Twin Cities music scene through various venues. Great jazz musicians have passed through the influential Artists' Quarter, first established in the 1970s in Whittier, Minneapolis, and moved to downtown Saint Paul in 1994.[94] Artists' Quarter also hosts the Soapboxing Poetry Slam, home of the 2009 National Poetry Slam Champions. At The Black Dog, in Lowertown, many French or European jazz musicians (Evan Parker, Tony Hymas, Benoît Delbecq, François Corneloup) have met Twin Cities musicians and started new groups touring in Europe. Groups and performers such as Fantastic Merlins, Dean Magraw/Davu Seru, Merciless Ghosts, and Willie Murphy are regulars. The Turf Club in Midway has been a music scene landmark since the 1940s.[95] Saint Paul is also the home base of the internationally acclaimed Rose Ensemble.[96] As an Irish stronghold, the city boasts popular Irish pubs with live music, such as Shamrocks, The Dubliner, and until its closure in 2019, O'Gara's.[97] The internationally acclaimed Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra is the nation's only full-time professional chamber orchestra.[98] The Minnesota Centennial Showboat on the Mississippi River began in 1958 with Minnesota's first centennial celebration.[99]

Saint Paul has a number of museums, including the University of Minnesota's Goldstein Museum of Design,[100] the Minnesota Children's Museum,[101] the Schubert Club Museum of Musical Instruments,[102][103] the Minnesota Museum of American Art,[104][105] the Traces Center for History and Culture,[106] the Minnesota History Center, the Alexander Ramsey House, the James J. Hill House, the Minnesota Transportation Museum, the Science Museum of Minnesota, and the Twin City Model Railroad Museum.

Sports

[edit]

The Saint Paul division of Parks and Recreation runs over 1,500 organized sports teams.[107]

Saint Paul hosts a number of professional, semi-professional, and amateur sports teams. The Minnesota Wild play their home games at downtown Saint Paul's Xcel Energy Center, which opened in 2000. The Wild brought the NHL back to Minnesota for the first time since 1993, when the Minnesota North Stars left the state for Dallas, Texas.[16] The World Hockey Association's Minnesota Fighting Saints played in Saint Paul from 1972 to 1977. Citing the history of hockey in the Twin Cities and teams at all levels, Sports Illustrated called Saint Paul the new Hockeytown U.S.A. in 2007.[108]

The Xcel Energy Center, a multipurpose entertainment and sports venue, can host concerts and accommodate nearly all sporting events. It occupies the site of the demolished Saint Paul Civic Center. The Xcel Energy Center hosts the Minnesota high school boys hockey tournament, the Minnesota high school girls' volleyball tournament, and concerts throughout the year. In 2004, it was named the best overall sports venue in the US by ESPN.[109]

The St. Paul Saints are the city's Minor League Baseball team, which plays in the International League as an affiliate of the Minnesota Twins.[110] There have been several different teams called the Saints over the years. Founded in 1884, they were shut down in 1961 after the Minnesota Twins moved to Bloomington. The Saints were brought back in 1993 as an independent baseball team in the Northern League, moving to the American Association in 2006. They joined affiliated baseball in 2021. Their home games are played at the open-air CHS Field in downtown's Lowertown Historic District.[111] Four noted Major League All-Star baseball players are natives of Saint Paul: Hall of Fame outfielder Dave Winfield, Hall of Fame infielder Paul Molitor, Hall of Fame pitcher Jack Morris, and Hall of Fame catcher and first baseman Joe Mauer, all of whom played for the Minnesota Twins during their careers. The all-black St. Paul Colored Gophers played four seasons in Saint Paul from 1907 to 1911.[112]

The St. Paul Twin Stars of the National Premier Soccer League play their home games at Macalester Stadium.[113] St. Paul's first curling club was founded in 1888. The current club, the St. Paul Curling Club, was founded in 1912 and is the largest curling club in the United States.[114] Minnesota Roller Derby is a flat-track roller derby league based in the Roy Wilkins Auditorium, made up of women and gender expansive athletes. Minnesota's oldest athletic organization, the Minnesota Boat Club, resides in the Mississippi River on Raspberry Island.[115] Saint Paul is also home to Circus Juventas, the largest circus arts school in North America.[116]

On March 25, 2015, Major League Soccer announced that it had awarded its 23rd MLS franchise to Minnesota United FC, a team from the lower-level North American Soccer League. Bill McGuire and his ownership group, which includes Jim Pohlad of the Minnesota Twins, Glen Taylor of the Minnesota Timberwolves, former Minnesota Wild investor Glen Nelson, and his daughter Wendy Carlson Nelson of the Carlson hospitality company, had intended to build a privately financed soccer-specific stadium in Downtown Minneapolis near the Minneapolis Farmer's Market. But their plan was met with heavy opposition from former Minneapolis Mayor Betsy Hodges, who said her city was suffering from "stadium fatigue" after building three stadiums for the Minnesota Twins, Minnesota Vikings and the Minnesota Golden Gophers, within a six-year span.[117] On July 1, 2015, after failing to reach an agreement with the city of Minneapolis, McGuire and his partners turned their focus to Saint Paul.[118]

On October 23, 2015, Bill McGuire of Minnesota United FC and former Saint Paul Mayor Chris Coleman announced that a privately financed soccer-specific stadium would be built on the vacant Metro Transit bus barn site in Saint Paul's Midway neighborhood near the intersection of Snelling Avenue and University Avenue. It is midway between downtown Saint Paul and downtown Minneapolis. The stadium, Allianz Field, opened in April 2019 and seats 19,400.[119] The team began playing in the MLS in 2017.[120]

The Minnesota Whitecaps began play in the Western Women's Hockey League in 2004 before going independent in 2010 when that league folded. In 2018, the Whitecaps joined the Premier Hockey Federation (then the National Women's Hockey League) as its fifth franchise.[121][122] The team won the Isobel Cup in its first season in the new league.[123] In the summer of 2023, the PHF ceased operations as part of the launch of a new, unified professional women's league, the Professional Women's Hockey League (PWHL).[124] Minnesota Frost was awarded one of the six charter franchises in the new league, and it was announced that the new team would play its home games at the Xcel Energy Center.[125][126]

The Timberwolves, Twins, Vikings, and Lynx all play in Minneapolis.[127]

| Club | Sport | League | Venue (capacity) | Championships |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minnesota Wild | Ice hockey | National Hockey League | Xcel Energy Center (17,954) | — |

| Minnesota Frost | Ice hockey | Professional Women's Hockey League | Xcel Energy Centre | PWHL: 2024 |

| Minnesota United FC | Soccer | Major League Soccer | Allianz Field (19,400) | NASL: 2011[128] and 2014[129] |

| Minnesota Wind Chill | Ultimate | Ultimate Frisbee Association | Sea Foam Stadium (3,500) | UFA: 2024 |

| St. Paul Saints | Baseball | International League | CHS Field (7,210) | NL: 1993, 1995, 1996, and 2004

AA: 2019 |

Government and politics

[edit]Saint Paul has a variant of the strong mayor–council form of government.[130] The mayor is the chief executive and chief administrative officer of the city and the seven-member city council is its legislative body.[131][132] The mayor is elected by the entire city, while members of the city council are elected from seven different geographic wards of approximately equal population.[133][134] The first female councilor, Elizabeth DeCourcy, was elected in 1956.[135] Municipal elections in Saint Paul use ranked choice voting.[136] Both the mayor and council members serve four-year terms.[137]

The current mayor is Melvin Carter (DFL), Saint Paul's first African-American mayor. Aside from Norm Coleman, who became a Republican during his second term, Saint Paul has not elected a Republican mayor since 1952.[138] As of 2024, following the 2023 elections, all seven city councilors are women, making Saint Paul potentially the largest city in American history with an all-female legislative body.[135]

The city is also the county seat of Ramsey County, named for Alexander Ramsey, the state's first governor. The county once spanned much of the present-day metropolitan area and was originally to be named Saint Paul County after the city. Today it is geographically the smallest county and the most densely populated.[6] Ramsey is the only home rule county in Minnesota; the seven-member Board of Commissioners appoints a county manager whose office is in the combination city hall/county courthouse along with the Minnesota Second Judicial Courts.[139][140] The nearby Law Enforcement Center houses the Ramsey County Sheriff's office.

State and federal

[edit]| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third party(ies) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| 2020 | 27,764 | 18.27% | 120,687 | 79.43% | 3,490 | 2.30% |

| 2016 | 23,530 | 16.86% | 104,226 | 74.68% | 11,800 | 8.46% |

| 2012 | 30,035 | 21.01% | 108,983 | 76.23% | 3,946 | 2.76% |

| 2008 | 31,667 | 22.38% | 106,926 | 75.58% | 2,883 | 2.04% |

| 2004 | 35,671 | 25.93% | 99,851 | 72.59% | 2,026 | 1.47% |

| 2000 | 32,520 | 26.65% | 77,158 | 63.22% | 12,369 | 10.13% |

Biden: 50–60% 60–70% 70–80% 80–90%

Saint Paul is the capital of Minnesota. The city hosts the capitol building, designed by Saint Paul resident Cass Gilbert, and the House and Senate office buildings. The Minnesota Governor's Residence, which is used for some state functions, is on Summit Avenue. The Minnesota Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party (affiliated with the Democratic Party) is headquartered in Saint Paul. Numerous state departments and services are also headquartered in Saint Paul, such as the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources.

The city is split into four Minnesota Senate districts (64, 65, 66 and 67) and eight Minnesota House of Representatives districts (64A, 64B, 65A, 65B, 66A, 66B, 67A and 67B), all of which are held by Democrats.[142][143]

Saint Paul is the heart of Minnesota's 4th congressional district, represented by Democrat Betty McCollum. The district has been in DFL hands without interruption since 1949. Minnesota is represented in the U.S. Senate by Democrat Amy Klobuchar, a former Hennepin County Attorney, and Democrat Tina Smith, a former lieutenant governor of Minnesota.

*District also includes Falcon Heights, Lauderdale and Roseville.

Education

[edit]

Saint Paul is second in the United States in the number of higher education institutions per capita, behind Boston.[144] Higher education institutions that call Saint Paul home include three public and eight private colleges and universities and five post-secondary institutions. Well-known colleges and universities include the Saint Catherine University, Concordia University, Hamline University, Macalester College, and the University of St. Thomas. Metropolitan State University and Saint Paul College, which focus on non-traditional students, are based in Saint Paul, as well as a law school, Mitchell Hamline School of Law.[145]

The Saint Paul Public Schools district is the state's largest school district and serves approximately 39,000 students. The district is extremely diverse with students from families speaking 90 different languages, although only five languages are used for most school communication: English, Spanish, Hmong, Karen, and Somali. The district runs 82 different schools, including 52 elementary schools, 12 middle schools, seven high schools, ten alternative schools, and one special education school, employing over 6,500 teachers and staff. The school district also oversees community education programs for pre-K and adult learners, including Early Childhood Family Education, GED Diploma, language programs, and various learning opportunities for community members of all ages. In 2006, Saint Paul Public Schools celebrated its 150th anniversary.[146] Some students attend public schools in other school districts chosen by their families under Minnesota's open enrollment statute.[147]

A variety of K-12 private, parochial, and public charter schools are also represented in the city. In 1992, Saint Paul became the first city in the US to sponsor and open a charter school, now found in most states across the nation.[148] Saint Paul is home to 21 charter schools and 38 private schools.[149] The Saint Paul Public Library system includes a central library, twelve branch locations, and a bookmobile.[150]

Media

[edit]

Saint Paul residents can receive 10 broadcast television stations, five of which broadcast from Saint Paul. One newspaper, the St. Paul Pioneer Press, and several monthly or semimonthly neighborhood papers serve the city. Several media outlets based in Minneapolis also serve the Saint Paul community, including the Star Tribune.

Saint Paul is home to two national broadcast companies. Hubbard Broadcasting is headquartered on the line between Saint Paul and Minneapolis on University Avenue.

Minnesota Public Radio (MPR) is a three-format system that broadcasts on nearly 40 stations[151] around the Midwest. It delivers local news and information, classical, and The Current (which plays a wide variety of music). The station has 110,000 regional members and more than 1 million listeners each week throughout the Upper Midwest, the largest audience of any regional public radio network.[152] Its parent company, American Public Media Group, creates and distributes programming that reaches millions listeners, most notably Marketplace, hosted by Kai Ryssdal.

Transportation

[edit]Interstate and roadways

[edit]

Residents use Interstate 35E running north–south and Interstate 94 running east–west. Trunk highways include U.S. Highway 52, Minnesota State Highway 280, and Minnesota State Highway 5. Saint Paul has several unique roads, such as Ayd Mill Road, Phalen Boulevard, and Shepard Road/Warner Road, that diagonally follow particular geographic features in the city. Biking is also gaining popularity, due to the creation of more paved bike lanes that connect to other bike routes throughout the metropolitan area[153] and the creation of Nice Ride Minnesota, a seasonally operated nonprofit bicycle sharing and rental system that has over 1,550 bicycles and 170 stations in both Minneapolis and Saint Paul.[154] Downtown Saint Paul has a five-mile (8 km) enclosed skyway system over 25 city blocks.[155] The 563-mile (906 km) Avenue of the Saints connects Saint Paul with St. Louis, Missouri.

The layout of city streets and roads has often drawn complaints. While he was Governor of Minnesota, Jesse Ventura appeared on the Late Show with David Letterman,[156] and remarked that the streets were designed by "drunken Irishmen".[157] He later apologized, though people had been complaining about the fractured grid system for more than a century by that point.[157] Some of the city's road design is the result of the curve of the Mississippi River, hilly topography, conflicts between developers of different neighborhoods in the early city, and grand plans only half-realized. Outside of downtown, the roads are less confusing, but most roads are named, rather than numbered, increasing the difficulty for non-natives to navigate.[158]

Mass transit

[edit]

Metro Transit provides bus service and light rail in the Minneapolis–Saint Paul area. The METRO Green Line is an 11-mile (18 km) light rail line that connects downtown Saint Paul to downtown Minneapolis with 14 stations in Saint Paul. The Green Line runs west along University Avenue, through the University of Minnesota campus, until it links up and then shares stations with the METRO Blue Line in downtown Minneapolis. Construction began in November 2010 and the line began service on June 14, 2014.[159][160] The Green Line averaged 42,500 rides per weekday in 2018.[161] Planning is underway for the Riverview Corridor, a rail line that will connect downtown Saint Paul to the airport and Mall of America.[162]

The METRO A Line opened in 2016 as Minneapolis–Saint Paul's first arterial bus rapid transit line. The A Line connects the Blue Line at 46th Street station to Rosedale Center with a connection at the Green Line Snelling Avenue station.[163] Future METRO lines are planned that will serve Saint Paul with the B Line and E Line Line running primarily on arterial streets, and the Gold Line and Purple Line running primarily in their own right of way.[164][165]

Railroad

[edit]Amtrak's Empire Builder between Chicago and Seattle or Portland stops twice daily in each direction at the newly renovated Saint Paul Union Depot.[166] Ridership on the train increased about 6% from 2005 to over 505,000 in fiscal year 2007.[167] A Minnesota Department of Transportation study found that increased daily service to Chicago should be economically viable, especially if it originates in Saint Paul and does not experience delays from the rest of the western route of the Empire Builder.[168] Based on that proposition, a new Amtrak line, the Borealis, began service on May 21, 2024, running the segment of the Empire Builder route between Saint Paul and Chicago, with several stops along the way, including one in Milwaukee.[169]

Saint Paul is the site of the Pig's Eye Yard, a major freight classification yard for Canadian Pacific Railway.[170] As of 2003, the yard handled over 1,000 freight cars per day.[170] Both Union Pacific and Burlington Northern Santa Fe run trains through the yard, though they are not classified at Pig's Eye.[170] BNSF operates the large Northtown Yard in Minneapolis, which handles about 600 cars per day.[171] There are several other small yards around the city.

Airports

[edit]Holman Airfield is across the river from Downtown St. Paul. Lamprey Lake was there until the Army Corps of Engineers filled it with dredgings starting in the early 1920s. Northwest Airlines began initial operations from Holman in 1926. During WWII Northwest had a contract to install upgraded radar systems in B-24s, employing 5,000 at the airfield. After WWII, Holman Airfield competed with the Speedway Field for the Twin Cities' growing aviation industry and lost out in the end. Today Holman is a reliever airport run by the Metropolitan Airports Commission. It is home to Minnesota's Air National Guard and a flight training school and is tailored to local corporate aviation. There are three runways, with the Holman Field Administration Building and Riverside Hangar on the National Register of Historic Places.[172] The original Northwest Airlines building's historical importance was realized only after demolition commenced.

For the most part Saint Paul's aviation needs are served by the Minneapolis–Saint Paul International Airport (MSP), which sits on 2,930 acres (11.9 km2) in the Fort Snelling Unorganized Territory bordering the city to the southwest. MSP serves 17 commercial passenger airlines[173] and is the hub of Delta Air Lines and Sun Country Airlines.[174]

Sister cities

[edit]Saint Paul's sister cities are:[175][176]

Changsha, China

Changsha, China Ciudad Romero, El Salvador

Ciudad Romero, El Salvador Culiacán, Mexico

Culiacán, Mexico Djibouti City, Djibouti

Djibouti City, Djibouti George, South Africa

George, South Africa Manzanillo, Mexico

Manzanillo, Mexico Modena, Italy

Modena, Italy Mogadishu, Somalia

Mogadishu, Somalia Nagasaki, Japan (from 1955 – the oldest sister city in Japan)

Nagasaki, Japan (from 1955 – the oldest sister city in Japan) Neuss, Germany

Neuss, Germany Novosibirsk, Russia

Novosibirsk, Russia Tiberias, Israel

Tiberias, Israel

Notable people

[edit]- Walter Abel (1898–1987), actor

- Loni Anderson (born 1946), actress

- Louie Anderson (1953–2022), comedian

- Wendell Anderson (1933–2016), U.S. senator

- Richard Arlen (1899–1976), actor

- Merrill Ashley (born 1950), ballet dancer and répétiteur

- Roger Awsumb (1928–2002), TV show host "Casey Jones"

- Azayamankawin (c. 1803–c. 1873), canoe ferry operator and entrepreneur known as "Old Bets"

- Harry Blackmun (1908–1999), U.S. Supreme Court associate justice, grew up in St. Paul

- Justin Braun (born 1987), hockey player

- Herb Brooks (1937–2003), hockey coach

- Warren E. Burger (1907–1995), U.S. Supreme Court chief justice

- Charles Burlingame (1949–2001), pilot of American Airlines Flight 77

- Melva Clemaire (1874–1937), soprano

- Laura Coates, attorney and media personality

- Nia Coffey (born 1995), WNBA player

- Kevin Eakin (born 1981), NFL player

- Sarah K. England, physiologist and biophysicist

- Robert J. Ferderer (1934–2009), politician and businessman

- F. Scott Fitzgerald (1896–1940), author

- David Graham (born 1953), American architect

- Daniel W. Hand (1869–1945), U.S. Army brigadier general[177]

- Josh Hartnett (born 1978), actor

- Andrew Osborne Hayfield (1905–1981), businessman and state legislator

- Mitch Hedberg (1968–2005), comedian

- James J. Hill (1838–1916), railroad tycoon

- Paul Holmgren (born 1955), NHL player, general manager, president of Philadelphia Flyers

- Nellie A. Hope (1864–1918), violinist, music teacher, orchestra conductor

- JoAnna James (born 1980), singer/songwriter

- Nick Jensen (born 1990), NHL player

- Timothy M. Kaine (born 1958), U.S. senator, governor of Virginia

- Rachel Keller (born 1992), actress

- Allan Kingdom (born 1993), rap artist

- Norman Kittson (1814–1888), fur trader integral to Saint Paul's foundation

- Jim Lange (1932–2014), TV presenter, game show host, and disc jockey

- Sunisa Lee (born 2003), Olympic gymnast and gold medalist

- Joe Mauer (born 1983), MLB player

- Ryan McDonagh (born 1989), NHL player

- Margaret Bischell McFadden, philanthropist and social worker

- K'Andre Miller (born 2000), NHL player

- Kate Millett (1934–2017), scholar, author

- Paul Molitor (born 1956), MLB player

- Jack Morris (born 1955), MLB player

- LeRoy Neiman (1921–2012), artist

- Kyle Okposo (born 1988), NHL player

- Bruce Olson (born 1941), missionary

- Tim Pawlenty (born 1960), governor of Minnesota

- Alfred E. Perlman (1902–1983), president of New York Central Railroad and its successor, Penn Central

- Dave Peterson (1931–1997), teacher and coach of the United States men's national ice hockey team[178]

- Emily Rudd (born 1993), actress

- Charles M. Schulz (1922–2000), cartoonist, born in Minneapolis, grew up in St. Paul

- Ervin Harold Schulz (1911–1978), newspaper editor, state representative, grew up in Saint Paul

- Meta Schumann (1887–1937), composer

- Joe Shiely Sr (1885–1972), civic leader and industrialist

- Chad Smith (born 1961), drummer of the Red Hot Chili Peppers since 1988, born in Saint Paul

- William Smith (1831–1912), paymaster-general of the United States Army, worked in and retired to St. Paul[179]

- Terrell Suggs, NFL player

- W.A. Swanberg (1907–1992), biographer

- Frances Tarbox (1874–1959), composer

- Fred Tschida (born 1949), artist, born in Saint Paul

- Lindsey Vonn (born 1984), Olympic skier and gold medalist

- DeWitt Wallace (1889–1981), magazine publisher and co-founder of Reader's Digest

- Dave Winfield (born 1951), MLB player

Medal of Honor recipients:

- Civil War: Private Marshall Sherman, Co C 1st Minnesota captured the flag of the 28th Virginia Infantry at Gettysburg

- Indian Wars: Pvt. John Tracy G Co. 8th Cavalry Chiricahua Mountains, Arizona, Apache War

- Indian Wars: Charles H. Welch, I Co. 9th Cavalry (Buffalo soldiers) Ghost Dance War

- Spanish-American War: Captain Jesse Dyer USMC, Vera Cruz, Mexico

- World War II: Captain Richard Fleming USMC VMA-241 Squadron, for whom Fleming Field is named

- Korean War: Lt. Colonel John Page, U.S. Army, Battle of Chosin Reservoir

See also

[edit]- Minneapolis–Saint Paul

- USS Saint Paul, 5 ships (including 2 as Minneapolis-Saint Paul)

References

[edit]- ^ St. Paul Charter §1.04

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- ^ a b "City of Saint Paul". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved December 9, 2024.

- ^ a b "Explore Census Data". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 7, 2022.

- ^ a b "City and Town Population Totals: 2020-2022". United States Census Bureau. October 12, 2023. Retrieved October 12, 2023.

- ^ a b "Ramsey County". Metro MSP. Minneapolis Regional Chamber Development Foundation. 2008. Archived from the original on July 8, 2008. Retrieved July 30, 2008.

- ^ "The St. Paul and Pacific was a pioneering railroad in Minnesota, if not a very successful one (at least, at first)". MinnPost. January 30, 2017. Archived from the original on November 6, 2021. Retrieved November 6, 2021.

- ^ "A City Where People Work". Capital City Partnership. 2006. Archived from the original on April 27, 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "About Saint Paul". Saint Paul, Minnesota. Archived from the original on December 1, 2021. Retrieved December 1, 2021.

- ^ "Saint Paul: Minnesota's Livable & Dynamic Capital City". Saint Paul, Minnesota. Archived from the original on December 1, 2021. Retrieved December 1, 2021.

- ^ "Cleveland.com News". Cleveland.com. January 30, 2019. Archived from the original on January 26, 2022. Retrieved January 28, 2022.

- ^ "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Archived from the original on April 21, 2019. Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- ^ "Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas on July 1, 2018 Population Estimates: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2018". U.S. Census Bureau. June 1, 2018. Retrieved June 1, 2018.[dead link] Alt URL[permanent dead link]

- ^ "An Early History of Saint Paul". Visit Saint Paul.

- ^ Fun Facts, Visit St. Paul, Official Convention and Visitors Bureau webpage, 175 West Kellogg Boulevard, Suite 502, Saint Paul, MN [1] Archived September 27, 2020, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "Stars Can't Go Home Again". CBS Sports. Associated Press. December 17, 2000. Archived from the original on December 11, 2008. Retrieved July 30, 2008.

- ^ a b Trimble, Steve (July 2, 2000). "A Short history of Indian Mounds Park". Neighborhood Pride Celebration. daytonsbluff.org. Archived from the original on May 1, 2011. Retrieved December 7, 2006.

- ^ "Indian Mounds Park". Mississippi National River and recreation Area. National Park Service. Archived from the original on January 18, 2011. Retrieved December 20, 2010.

- ^ a b Morrison, Mark (2008). "Dakota Life". City of Bloomington. Archived from the original on May 1, 2008.

- ^ Stephen Return Riggs; James Owen Dorsey (1892). A Dakota-English Dictionary. University of Michigan. p. 197. Retrieved July 30, 2008.

imniza ska.

- ^ a b "Lambert's Landing". National Park Services. February 16, 2023. Archived from the original on June 7, 2023.

- ^ Hoffman, Mike. "Menominee Place Names in Wisconsin". The Menominee Clans Story. Archived from the original on October 5, 2018. Retrieved October 6, 2018.

- ^ "The Treaty Story". Minnesota History Center. 1999. Archived from the original on January 5, 2009.

- ^ "Treaty with the Sioux, 1837". Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties. Oklahoma State University Library. September 29, 1837. Archived from the original on December 1, 2008. Retrieved July 15, 2016.

- ^ 1983 Survey Dist 1.pdf - Historic Saint Paul, Historic Saint Paul website, 400 Landmark Center, 75 West 5th Street, Saint Paul, MN [2] Archived November 27, 2020, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kappler, Charles J., ed. (1904). Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties. Vol. II (Treaties, 1778–1883). Government Printing Office – via Oklahoma State University Library. and "Treaty with the Sioux". September 29, 1837. Archived from the original on December 1, 2008. and "Treaty with the Sioux—Sisseton and Wahpeton Bands". July 23, 1851. Archived from the original on June 16, 2008. and "Treaty With the Sioux—Mdewakanton and Wapahkoota Bands". August 5, 1851. Archived from the original on July 11, 2007. Retrieved June 26, 2007.

- ^ a b c Schaper, Julie; Horwitz, Steven (2006). Twin Cities Noir. New York, New York: Akashic Books. pp. 16. ISBN 978-1-888451-97-9. Retrieved July 28, 2008.

- ^ Carver's Cave- Subterranean Twin Cities, Ramsey County History, G.A. Brick, p.17 [3] Archived November 28, 2020, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Pierre Bottineau, GENi, Joe Eickhoff, July 2020". Archived from the original on April 29, 2021. Retrieved September 4, 2020.

- ^ "Overview of the Cathedral". Cathedral of Saint Paul. 2004. Archived from the original on August 6, 2007.

- ^ Mougel, Patricia (June 2007). "Catholicisme dans le Midwest Lucien Galtier et l'origine du nom de la capitale du Minnesota" (PDF) (in French). Reflets de l'étoile du nord. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 9, 2008. Retrieved July 28, 2008.

- ^ a b Gilman, Rhonda R. (1989). The Story of Minnesota's Past. Saint Paul, Minnesota: Minnesota Historical Society Press. pp. 99–104. ISBN 978-0-87351-267-1.

- ^ "MNDOT Historic Roadside Development Structures Inventory, RA-SPC-2928" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 19, 2020. Retrieved September 9, 2020.

- ^ "Rolette, Jr., Joseph "Joe"". Minnesota Legislators Past & Present. Minnesota Legislature. Archived from the original on December 29, 2008. Retrieved July 30, 2008.

- ^ a b Wingerd, Mary Lethert. "Separated at Birth: The Sibling Rivalry of Minneapolis and St. Paul". Organization of American Historians. Archived from the original on July 7, 2012. Retrieved November 19, 2007.

- ^ "St. Paul, Minneapolis and other cities in Minnesota suffer from gale". GenDisasters.com. Archived from the original on October 22, 2007. Retrieved March 28, 2008.

- ^ "Rondo Neighborhood & the Building of I-94". Minnesota Historical Society. 2008. Archived from the original on February 4, 2013. Retrieved July 2, 2008.

- ^ Davis, F. James (1965). "The Effects of a Freeway Displacement on Racial Housing Segregation in a Northern City". Phylon. 26 (3): 209–215. doi:10.2307/273848. JSTOR 273848.

- ^ "Rondo Days official site". Rondo Avenue Inc. Archived from the original on May 1, 2008. Retrieved August 3, 2008.

- ^ "Tallest skyscrapers of Saint Paul". Emporis. 2008. Archived from the original on May 18, 2007. Retrieved August 15, 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Hmong Refugee Resettlement". Minnesota Council of Non-Profits. Archived from the original on February 2, 2008. Retrieved March 28, 2008.

- ^ Moua, Teng. "Hmong Archives Reaches a Milestone". Hmong Today. Archived from the original on May 15, 2011. Retrieved December 18, 2010.

- ^ "Mississippi: River Facts". U.S. National Park Service. August 14, 2006. Archived from the original on January 6, 2009. Retrieved July 28, 2008.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 2, 2012. Retrieved November 13, 2012.

- ^ Havens, Chris (October 31, 2007). "In St. Paul, they're passionate about parks". Star Tribune. pp. AA1. ISSN 0895-2825. Archived from the original on November 2, 2007. Retrieved November 4, 2007.

- ^ "ParkScore". www.parkscore.tpl.org. Archived from the original on May 24, 2018. Retrieved May 23, 2018.

- ^ Medcalf, Myron P. (September 11, 2007). "St. Paul's neighborhood councils scrutinize their financial status". Star Tribune. pp. B4 Local. Archived from the original on March 10, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2008.

- ^ "District Councils". City of Saint Paul. 2008. Archived from the original on February 11, 2009.

- ^ Kottek, Markus; Grieser, Jürgen; Beck, Christoph; Rudolf, Bruno; Rubel, Franz (June 2006). "World Map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification updated". Meteorologische Zeitschrift. 15 (3): 259–263. Bibcode:2006MetZe..15..259K. doi:10.1127/0941-2948/2006/0130. Retrieved December 15, 2010.[permanent dead link]

- ^ 45.4 °F for 1971 through 2000 per U.S. Census Archived January 3, 2007, at the Wayback Machine who cites "Normals 1971–2000". National Climatic Data Center. Archived from the original on April 1, 2007. Retrieved March 25, 2007. or 44.6 °F (7.0 °C) per Fisk, Charles (March 3, 2007). "Minneapolis-Saint Paul Area Daily Climatological History of Temperature, Precipitation, and Snowfall, A Year-by-Year Graphical Portrayal (1820–present)". Archived from the original on May 18, 2007. Retrieved March 25, 2007.

- ^ "Saint Paul Climate Action & Resilience Plan" (PDF). stpaul.gov. December 2019. Retrieved February 27, 2024.

- ^ "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on August 17, 2021. Retrieved June 22, 2021.

- ^ "Station: St Paul Downtown AP, MN". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991-2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on June 24, 2021. Retrieved June 22, 2021.

- ^ "Seasonal Temperature and Precipitation Information". The Weather Channel. August 2011. Archived from the original on May 10, 2008. Retrieved July 28, 2008.

- ^ United States Census Bureau. "Census of Population and Housing". Archived from the original on March 21, 2021. Retrieved June 9, 2014.

- ^ "2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171)". US Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 12, 2022. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ "St. Paul (city), Minnesota". State & County QuickFacts. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on September 16, 2008.

- ^ "Race and Hispanic or Latino: 2000". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved June 14, 2017.

- ^ a b "Race and Hispanic Origin for Selected Cities and Other Places: Earliest Census to 1990". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on August 12, 2012. Retrieved April 20, 2012.

- ^ a b From 15% sample

- ^ "2020 Decennial Census: St. Paul city, Minnesota". data.census.gov. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved January 1, 2023.

- ^ a b c d "The Demographic Statistical Atlas of the United States - Statistical Atlas". statisticalatlas.com. Retrieved March 20, 2024.

- ^ "Group Quarters Population, 2020 Census: St. Paul city, Minnesota". data.census.gov. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved January 1, 2023.

- ^ "Selected Economic Characteristics, 2020 American Community Survey: St. Paul city, Minnesota". data.census.gov. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved January 1, 2023.

- ^ "Selected Social Characteristics, 2020 American Community Survey: St. Paul city, Minnesota". data.census.gov. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved January 1, 2023.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved November 13, 2012.

- ^ Lanegran, David A. (2001). "From Swede Hollow to Arlington Hills, From Snoose Boulevard to Minnehaha Parkway: Swedish Neighborhoods of the Twin Cities" (PDF). Macalester College. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 24, 2008. Retrieved July 28, 2008.

- ^ "District 7: Thomas-Dale or Frogtown". Ramsey County Historical Society. 2005. Archived from the original on April 11, 2008.

- ^ Kenworthy, Tom (November 29, 2004). "Hmong get closer look since shootings". USA Today. Archived from the original on June 30, 2012. Retrieved September 11, 2017.

- ^ "Hmong Resettlement Revisited". Bridging Refugee Youth and Children's Services. June 2004. Archived from the original on August 23, 2007. Retrieved November 4, 2007.

- ^ "Homepage | Literacy Minnesota". www.literacymn.org. Retrieved March 20, 2024.

- ^ "Saint Paul Ethnic Population Growth". City of Saint Paul. Archived from the original on January 16, 2009. Retrieved November 6, 2007.

- ^ Toness, Bianca Vazquez (May 24, 2005). "Mexican consulate opens in June". Minnesota Public Radio. Archived from the original on September 18, 2006. Retrieved November 6, 2007.

- ^ Tour | African American Heritage: Points of Entry

- ^ "Ramsey County, Minnesota". Religious Congregations and Membership in the United States, 2000. Association of Religion Data Archives. Archived from the original on December 5, 2010. Retrieved December 21, 2010.

- ^ Gihring, Tim (April 2009). "Welcome to Paganistan". Minnesota Monthly. Archived from the original on September 8, 2011. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ "Databases, Tables & Calculators by Subject". Bureau of Labor Statistics. U.S. Department of Labor. August 26, 2008. Archived from the original on March 10, 2022. Retrieved August 26, 2008. This data may not be directly reproducible via this link. BLS.gov Archived September 12, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, Select "27 Minnesota" and "33460 Minneapolis–St. Paul–Bloomington, MN-WI" and all subsectors.

- ^ Orrick, Dave (July 28, 2008). "Downtown goal: Fill storefronts — at least for now". Pioneer Press. MediaNews Group. Archived from the original on August 3, 2008. Retrieved July 30, 2008.

- ^ Johnson, Kim (August 20, 2008). "Business Journal names Best Places to Work". Minneapolis / St. Paul Business Journal. American City Business Journals. Archived from the original on May 19, 2009. Retrieved August 26, 2008.

- ^ Abbe, Mary (July 21, 2008). "Same old struggles at the MMAA". Star Tribune. Chris Harte. p. 3. Archived from the original on September 18, 2008. Retrieved July 21, 2008.

- ^ "Lock and Dam 1". St. Paul District. US Army Corps of Engineers. Archived from the original on December 6, 2008. Retrieved August 27, 2008.

- ^ Bloomquist, Madison (November 8, 2022). "Big Picture: Highland Bridge". Mpls. St. Paul. Archived from the original on December 3, 2022. Retrieved March 5, 2023.

- ^ "Frederick Melo: You don't know TIF!". Twin Cities. April 14, 2018. Archived from the original on April 15, 2018. Retrieved April 15, 2018.

- ^ Melo, Frederick (September 7, 2022). "St. Paul City Council likely to prune rent-control ordinance next week". St. Paul Pioneer Press. Retrieved September 27, 2022.

- ^ a b Nesterak, Max (September 21, 2022). "St. Paul City Council passes sweeping overhaul of rent control ordinance". Minnesota Reformer. Retrieved March 5, 2023.

- ^ Galioto, Katie (September 20, 2022). "St. Paul leaders poised to limit controversial rent control policy". Star Tribune. Retrieved September 27, 2022.

- ^ Melo, Frederick (September 21, 2022). "St. Paul City Council amends rent control, exempts new construction with 5-2 vote". St. Paul Pioneer Press. Retrieved September 27, 2022.

- ^ Ice Palaces in Montreal 1883-89, The Ice Cubicle, [4] Archived October 14, 2020, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "History of the Saint Paul Winter Carnival". St Paul Winter Carnival. 2008. Archived from the original on May 17, 2008. Retrieved July 2, 2008.

- ^ "Harry F. Schroeder, Jr. The Kid After Whom Charles M. Schulz Named His Beethoven-Loving Character in His "Peanuts" Cartoon". Delehanty – Sullivan – Kinsman – Schroeder Family History Workspace. 2006. Archived from the original on July 29, 2012.

- ^ "Saint Paul kicks off encore to the successful 'Peanuts on Parade' summer art project". PRnewswire.co.uk. Archived from the original on May 27, 2012. Retrieved August 13, 2008.

- ^ "John Vachon: A Register of His Papers in the Library of Congress". Prepared by Connie L. Cartledge. Manuscript Division, Library of Congress. 2006. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved October 10, 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "Ordway Center for the Performing Arts". Ordway Center for the Performing Arts. 2006. Archived from the original on December 5, 2006. Retrieved December 7, 2006.

- ^ Berryman, Don (April 21, 2004). "Artists' Quarter". Jazz Police. Archived from the original on July 5, 2008. Retrieved July 30, 2008.

- ^ Gelhhar, Jenny (2007). "The Turf Club". Features. Saint Paul Almanac. Archived from the original on January 6, 2009. Retrieved July 30, 2008.

- ^ "History of the Rose Ensemble". Archived from the original on December 22, 2008. Retrieved November 23, 2008.

- ^ Belcamino, Kristi (November 4, 2019). "O'Gara's Bar and Grill, a landmark St. Paul institution, won't reopen". Twin Cities.com. St. Paul Pioneer Press. Archived from the original on April 29, 2021. Retrieved March 23, 2021.

- ^ "Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra Three concerts". University of Chicago. 2008. Archived from the original on May 31, 2008.

- ^ "Minnesota Centennial Showboat!". University of Minnesota. July 3, 2008. Archived from the original on June 25, 2008. Retrieved July 29, 2008.

- ^ "Goldstein Museum of Design". College of Design. Regents of the University of Minnesota. 2008. Archived from the original on June 25, 2008. Retrieved July 31, 2008.

- ^ "Hours, Parking, and Directions". Visitor Information. Minnesota Children's Museum. 2010. Archived from the original on December 13, 2010. Retrieved December 19, 2010.

- ^ Ong, Bao (July 31, 2006). "Carlson's legacy: Schubert Club: Thanks to him, once-tiny arts group attracts top artists to Twin Cities". Pioneer Press. Archived from the original (registration required) on December 31, 2008. Retrieved July 31, 2008.

- ^ "Schubert Club Museum of Musical Instruments". The Schubert Club. 2008. Archived from the original on September 21, 2008. Retrieved July 31, 2008.

- ^ Wyant, Carissa (July 26, 2008). "St. Paul art museum loses director; searches for new home". Minneapolis St. Paul Business Journal. American City Business Journals, Inc. Archived from the original on August 1, 2008. Retrieved July 25, 2008.

- ^ Abbe, Mary (July 21, 2008). "Same old struggles at the MMAA". Star Tribune. Chris Harte. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 18, 2008. Retrieved July 21, 2008.

- ^ "St. Paul Culture: Museums". M.R. Danielson Advertising Associates. 2002. Archived from the original on October 31, 2007. Retrieved December 7, 2006.

- ^ Schulman, Andrew. "St. Paul takes SI Sportstown Honors for the Land of 10,000 Lakes". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on October 7, 2007. Retrieved October 30, 2007.

- ^ Farber, Michael (December 4, 2007). "In Search of... Hockeytown U.S.A". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on May 11, 2008. Retrieved August 5, 2008.

- ^ "About Xcel Energy Center". Minnesota Twins. Archived from the original on August 12, 2007. Retrieved October 30, 2007.

- ^ Mayo, Jonathan (February 12, 2021). "MLB Announces New Minors Teams, Leagues". Major League Baseball. Archived from the original on March 6, 2021. Retrieved February 12, 2021.

- ^ "St. Paul Baseball History". St. Paul Saints. Archived from the original on July 17, 2006. Retrieved August 13, 2008.

- ^ Sheldon, Mark (February 7, 2003). "Colored Gophers made history". MLB.com. Archived from the original on January 17, 2008. Retrieved October 30, 2007.

- ^ "About Us". St. Paul Twin Stars. Archived from the original on July 12, 2014. Retrieved December 19, 2010.

- ^ "About the St. Paul Curling Club". Saint Paul Curling Club. Archived from the original on February 16, 2007.

- ^ "Minnesota Boat Club". Archived from the original on May 11, 2008. Retrieved August 28, 2008.

- ^ Pioneer Press staff (June 19, 2012). "Tickets for Circus Juventas summer show announced". St. Paul Pioneer Press. Archived from the original on January 15, 2016. Retrieved October 4, 2014.

- ^ Ervin, Phil (May 19, 2015). "MLS fight won, Minnesota United still going through 'process' of financing facility". Archived from the original on December 11, 2015. Retrieved October 24, 2015.

- ^ "MLS Turns to St. Paul After United FC Misses Stadium Deadline for Expansion Rights". Minneapolis/St. Paul Business Journal. Archived from the original on July 5, 2015. Retrieved October 24, 2015.

- ^ "Fast Facts". mnufc.com. Archived from the original on July 12, 2017.

- ^ Gonzalez, Roger (March 12, 2017). "Look: Minnesota United plays first MLS home match in the pouring snow". Archived from the original on September 5, 2018. Retrieved September 5, 2018.

- ^ Thiede, Dana (May 15, 2018). "MN Whitecaps join National Women's Hockey League". kare11.com. Archived from the original on March 10, 2022. Retrieved September 5, 2018.

- ^ Wawrow, John (September 7, 2021). "NWHL Rebrands to 'Premier Hockey Federation' to Promote Inclusivity, Inspire Youth". WNBC. Archived from the original on October 20, 2021. Retrieved November 9, 2021.

- ^ Mizutani, Dane (March 17, 2019). "Minnesota Whitecaps capture Isobel Cup championship in inaugural NWHL season". Pioneer Press. Archived from the original on March 5, 2020. Retrieved January 6, 2024.

- ^ Wyshynski, Greg (June 29, 2023). "Sources: Premier Hockey Federation sale could unite women's hockey". ESPN. Archived from the original on June 30, 2023. Retrieved January 6, 2024.

- ^ "PWHL unveils locations of first six teams, player selection process". Sportsnet. AP. August 29, 2023. Archived from the original on August 30, 2023. Retrieved January 6, 2024.

- ^ Kennedy, Ian (November 28, 2023). "PWHL Officially Announces Venues". The Hockey News. Archived from the original on November 29, 2023. Retrieved January 6, 2024.

- ^ "Professional Sports". Meet Minneapolis. 2011. Archived from the original on December 1, 2008. Retrieved February 14, 2011.

- ^ Quarstad, Brian (October 30, 2011). "NSC Minnesota Stars Win the 2011 NASL Championship". Archived from the original on December 11, 2015. Retrieved October 24, 2015.

- ^ "Minnesota United crowned 2014 NASL spring champion". Archived from the original on April 1, 2019. Retrieved September 15, 2019.

- ^ "Description of Saint Paul's Form of Government". 2008 Mayor's Proposed Budget. City of Saint Paul. Archived from the original (pdf) on December 11, 2008. Retrieved November 10, 2007.

- ^ "Sec. 2.01. Chief executive". Administrative Code. City of Saint Paul. Retrieved November 10, 2007.[dead link]

- ^ "Sec. 4.01. Legislative power". Saint Paul City Charter. City of Saint Paul. Archived from the original on December 14, 2012. Retrieved November 11, 2007.

- ^ "Sec. 2.01. Elective officials". Saint Paul City Charter. City of Saint Paul. Archived from the original on December 14, 2012. Retrieved November 11, 2007.

- ^ "Sec. 4.01.2. Initial districts". Saint Paul City Charter. City of Saint Paul. Archived from the original on December 14, 2012. Retrieved November 10, 2007.

- ^ a b Galioto, Katie; Boone, Anna; Steinberg, Jake (January 8, 2024). "St. Paul will swear in its first all-female City Council on Tuesday. How did we get here?". Star Tribune. Retrieved January 8, 2024.

- ^ "Ranked Voting". Ramsey County. June 10, 2015. Retrieved September 13, 2023.

- ^ "Sec. 2.02. Terms". Saint Paul City Charter. City of Saint Paul. Archived from the original on February 17, 2003. Retrieved November 10, 2007.

- ^ Ostermeier, Eric J. "Twin Cities Mayoral Historical Overview" (PDF). Center for the Study of Politics and Governance. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 25, 2008. Retrieved January 1, 2008.

- ^ "Ramsey County Home Rule Charter". Ramsey County. 2008. Archived from the original on October 18, 2008.

- ^ "Ramsey County Building Locations". Ramsey County. 2008. Archived from the original on December 21, 2008.

- ^ "Minnesota Election Results". Office of the Minnesota Secretary of State. Retrieved August 13, 2024.

- ^ "Minnesota Senate Maps & Data". Geographic Information Services. Minnesota State Legislature. 2007. Archived from the original on September 16, 2008. Retrieved July 24, 2008.

- ^ "Minnesota House Maps & Data". Geographic Information Services. Minnesota State Legislature. 2007. Archived from the original on September 16, 2008. Retrieved July 24, 2008.

- ^ El Nasser, Haya (April 11, 2004). "Most livable? Depends on your definition". USA TODAY. Archived from the original on October 15, 2007. Retrieved October 16, 2007.

- ^ "Post-Secondary Schools". Minnesota Department of Education. 2005. Archived from the original on December 12, 2006. Retrieved March 24, 2007.

- ^ Saint Paul Public Schools. "About Us". Archived from the original on June 4, 2007. Retrieved June 8, 2007.

- ^ "Open Enrollment". Minnesota Department of Education. Archived from the original on August 26, 2010. Retrieved November 19, 2010.

- ^ "Charter School Facts". MN Association of Charter Schools. Archived from the original on October 24, 2007. Retrieved November 6, 2007.

- ^ Minnesota Department of Education (2005). "Alphabetical List of Nonpublic Schools". Archived from the original on August 18, 2007. and "Charter Schools". 2005. Archived from the original on June 1, 2007. Retrieved June 8, 2007.

- ^ "Find a Location". Saint Paul Public Library. 2021. Archived from the original on November 5, 2021. Retrieved November 5, 2021.

- ^ "Stations". Minnesota Public Radio. 2008. Archived from the original on September 18, 2008. Retrieved August 27, 2008.

- ^ "Company Information". Minnesota Public Radio. 2008. Archived from the original on September 18, 2008. Retrieved August 27, 2008.

- ^ "Bike-n-Ride by bus". Metro Transit. Archived from the original on August 20, 2007. Retrieved September 20, 2007.

- ^ "Nice Ride Minnesota: Ambitious plans set for 2014 season". Star Tribune. Archived from the original on October 31, 2013. Retrieved November 16, 2013.