Speculative fiction by writers of color

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Speculative fiction is defined as science fiction, fantasy, and horror. Within those categories exists many other subcategories, for example cyberpunk, magical realism, and psychological horror.

"Person of color" is a term used in the United States to denote non-white persons, sometimes narrowed to mean non-WASP persons or non-Hispanic whites, if "ethnic whites" are included. The term "person of color" is used to redefine what it means to be a part of the historically marginalized racial and ethnic groups within Western society. A writer of color is a writer who is a part of a marginalized culture in regards to traditional Euro-Western mainstream culture. This includes Asians, African-Americans, Africans, Native Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans, and Pacific Islanders.

While writers of color may sometimes focus on experiences unique to their cultural heritage, which have sometimes been considered "subcategories" of national heritage (e.g. the black experience within American culture), many do not only write about their particular culture or members within that culture, in the same way that many Americans of European descent (traditionally categorized as Caucasian or white) do not only write about Western culture or members of their cultural heritage. The works of many well-known writers of color tend to examine issues of identity politics, religion, feminism, race relations, economic disparity, and the often unacknowledged and rich histories of various cultural groups.

African-American speculative fiction

[edit]African-American science fiction and fantasy

[edit]Black speculative fiction often focuses on race and the history of race relations in Western society. The history of slavery, the African diaspora, and the Civil Rights Movement sometimes influence the narrative of SF stories written by black authors. Within science fiction, the concern is that many traditional science fiction works do not include black people in the future under any context, or only in sidelined roles.

As the popularity of science fiction and other speculative genres grows within the black community, some longtime fans and black writers branch out to write about "universal" themes that cross cultural lines and feature African and African-American protagonists. These stories and novels may not deal heavily with issues concerning race but instead primarily focus on other aspects of life. They are notable because, historically, many science fiction works that deal with traditional science fiction subject matter do not feature characters of color.

The cultural significance of science fiction works by black writers is being recognized in the mainstream as more fans indicate a desire for stories that reflect their interests in speculative fiction and also reflect their unique experiences as people of color. Non-POC fans are also interested in these works. While they may or may not identify with the cultural contexts of the work, they can and do identify with the characters within the context of the story and enjoy the science fiction themes and plots. This is indicated by the popularity of writers like Octavia E. Butler, Walter Mosley, Nalo Hopkinson, Jeffery Renard Allen, and Tananarive Due.

The contributions of writers such as Octavia E. Butler, usually credited as the first black woman to gain widespread acclaim and recognition as a speculative fiction writer, have influenced the works of new generations of SF writers of color.

Hope Wabuke, a writer and assistant professor at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln of English and Creative Writing, argues that the term "Black Speculative Literature" can encompass the terms Afrofuturism, Africanfuturism, and Africanjujuism, the latter two coined by Nnedi Okorafor, all of which center "African and African diasporic culture, thought, mythos, philosophy, and worldviews."[1]

See also

[edit]African-American, African-Canadian, and African-British science fiction, fantasy, and horror

[edit]- Linda Addison (poet)

- Leslie Esdaile Banks

- Steven Barnes

- K. Tempest Bradford

- Maurice Broaddus

- Octavia Butler

- P. Djèlí Clark

- Samuel R. Delany

- Nicky Drayden

- Tananarive Due

- Sutton Griggs (Sutton E. Griggs)

- Virginia Hamilton

- Ehigbor Okosun

- Andrea Hairston

- Nalo Hopkinson

- N. K. Jemisin

- Alaya Dawn Johnson

- Victor Lavalle

- Walter Mosley

- Charles Saunders

- Geoffrey Thorne

- Jewelle Gomez

- Tomi Adeyemi

- Namina Forna

- Kai Ashante Wilson

- Colson Whitehead

- Jordan Ifueko

- Tracy Deonn

- Holland, Jesse

- L.L. McKinney

- Schuyler, George

- Justina Ireland

- Kamal Mansour

- Kimberly Drew

- Janelle Monáe

- Mohammed Dib

- Dilman Dila

- Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki

- Chukwuemeka Ike

- Kojo Laing

- Nnedi Okorafor

- Ben Okri

- Tochi Onyebuchi

- Sofia Samatar

- Sony Lab'ou Tansi

- Ahmed Khaled Tawfik

- Sheree Renée Thomas

- Tade Thompson

- Amos Tutuola

- Abdourahman Waberi

- Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o

- Minister Faust

- Kacen Callendar

- Ishmael Reed

- Toyin Omoyeni Falola

- Nuzo Onoh

- Eloghosa Osunde

- C. L. Polk

- Lisa Yaszek

See also:

Arab speculative fiction

[edit]Arab speculative fiction is speculative fiction written by Arab authors that commonly portrays themes of repression, cyclical violence, and the concept of a utopia long lost by years of destruction.[2] Culture specific subgenres have their own distinct themes from one another characterized by the experiences of those within their respective states. Two such states, the land referred to as Palestine, and Egypt, each have themes specific to their individual histories and cultural experiences.[3][4] Examples of themes in Palestinian Speculative Fiction include settler occupation, lost futures, and stoicism in the face of opposition.[3] Examples of themes in Egyptian Speculative Fiction include militant governments, repressed uprisings, and totalitarianism.[4]

Palestinian speculative fiction

A subsection of Arab Speculative Fiction is that of Palestinian Speculative Fiction, a subgenre written through the lens of the people of Palestine experiencing settler colonialism after the State of Israel was established in 1948, along with the concurrent effort to expel Palestinians from the claimed land, called Nakba.[3]

This subgenre includes different mediums of expression, including art, film, and literature.[3] The works of this subgenre focus on a range of present days and futures for Palestine.[3]

Some examples are tied to the irreparably changed routines of Palestinians, such as Tarzan and Arab's short film Condom Lead, which portrays a Palestinian family trapped underneath a 22-day-long Israeli assault.[3] The film includes depictions of troubled childcare, anxiety, and deprivation of sexual pleasure as a result of the assault.[3]

Other examples speculate Palestinian futures rendered impossible by the reality of the present, such as Rabah's The Palestinian Museum of Natural History and Human Kind. Rabah's conceptual, multisite exhibit blends fictional and real events to fabricate implausible Palestinian pasts and futures.[3] This exhibit is an exercise in the purpose and execution of museums, depicting a land and culture whose legitimacy is questioned.[3]

Amongst the themes present in Palestinian Speculative Fiction, there is the concept and practice of Sumūd, which is a uniquely Palestinian form of stoicism. In Palestinian Speculative Fiction, Sumūd portrays a form of rebellion in the act of endurance and perseverance in the face of constant struggle.[3] This passive resistance is the effort to fend off the erasure of Palestinian knowledge and cultural norms that comes with the acknowledgement that systemic destruction of the Palestinian people is a possibility.[3] This concept is present in Shibli's novella Masās, which depicts the third-person perspective of an unnamed Palestinian girl's life, who interprets her overwhelming surroundings through colors.[3] As she grows, she takes in the major and minute details of her surroundings, becoming resolute in the instability of her home and life by the time she's married at the end of the novel.[3]

Themes of Palestinian and cultural destruction have multiple levels, one of the simplest and most expansive being the act of Palestinian reproduction, and the deprivation of sexual recreation and pleasure.[3] These themes are present in Condom Lead.[3] These themes are presented both through the lens of children and afflicted adults under the assumption that ‘life must go on’, and many things must be left behind.[3]

Egyptian speculative fiction

Egyptian speculative fiction arguably dates back to as early as 1906.[5] In recent years, people from Egypt have been writing speculative fiction in response to the injustices they face.

Since a military coup in 2013, Egypt has been under a military rule. President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi has enforced an authoritative rule by severely punishing anyone who opposes, or has the threat of opposing, their actions.[4] Since then, people have been arrested for protesting, and have faced extreme punishments if the security forces have even suspicions of disagreeing with those in power. Because of the strict laws around protesting, many citizens switch to creative critiques instead. Since 2014, the security forces have shut down and prevented any public expression of the arts, calling them “suspicious”.[4] With activism and creativity being silenced and oppressed, many literary critics have turned to speculative fiction to express and comment on the dystopian qualities of their daily lives.

The works of Egyptian speculative writers, express themes such as anxiety of the possible punishment of expression, the pain that Egyptians are enduring under the military regime, and the effect of violence on the citizens. One example of speculative fiction is Otared by Egyptian writer Mohammed Rabie which follows an apocalyptic future in Egypt that ends in many deaths. Rabie expresses the pain of living under a military regime, that leads to love. Another author who works in the speculative genre, is Ahmed Khaled Towfik. He is one of the first Arab writers to write science-fiction. He inspired other authors such as Ahmed Mourad. Nawal El Saadawi was a feminist writer who wrote from the unique perspective of experience womanhood in a politically oppressive state.[6] Her 1975 novel, Woman at Point Zero, is based on a woman facing execution.[7] The novel is the woman's account of the oppression she faced as a woman in Egyptian society and goes on to express the feminist idea of female agency.[7]

Much of the speculative works coming from Egypt express the hopelessness that they feel under an authoritative rule. Many authors, however, still hold onto their agency as writers and critics.

Asian and Asian American speculative fiction

[edit]While the term Afrofuturism is widely used and accepted to explain the mingling of the African American experience with technology, science, and the future, a similar term, "Asianfuturism," has yet to catch on.[8] Popularity is growing for English translations of Chinese science fiction novels, but the number of Asian-American science fiction authors remains small and underrepresented.[9]

With various perspectives from the diaspora, many works of Asian speculative fiction present commentary on xenophobia, imperialism, environmental degradation, independence, identity, and belonging. Sometimes introducing elements of cyberpunk and the supernatural, works in this genre can also transport readers to a realm separate from reality while discussing similar themes. Asian speculative fiction allows readers a space for discovery and understanding of unfamiliar settings and norms with stories set in countries such as China, Japan, India, and many more.

Chinese American speculative fiction written by and about women work on creating the feeling of nostalgia in readers, focusing in on experiences by second-generation Americans.[10] Women's experiences are also explored through the lens of cyberpunk fiction, with an emphasis on the female body.[11]

Japanese speculative fiction

[edit]Japanese speculative fiction, encompassing a diverse range of literary works, has a rich history deeply intertwined with the country's cultural and social contexts. Often characterized by its imaginative narratives, futuristic themes, and exploration of societal issues,[12] Japanese speculative fiction has gained international recognition for its unique blend of traditional storytelling elements with modern speculative concepts.

History and influences

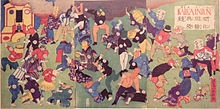

[edit]The roots of Japanese speculative fiction can be traced back to ancient folklore, where mythical creatures and supernatural phenomena played prominent roles in storytelling.[13] However, the genre began to evolve significantly during the Meiji Restoration in the late 19th century, as Japan rapidly modernized and embraced Western ideas. Influences from Western science fiction literature, particularly the works of Jules Verne and H.G. Wells, started to permeate Japanese culture, laying the groundwork for the emergence of modern speculative fiction.

Early pioneers

[edit]

One of the earliest pioneers of Japanese speculative fiction was Rampo Edogawa, a pen name of Hirai Taro, who gained prominence in the early 20th century for his psychological thrillers and surrealistic narratives. His works, such as "The Human Chair" (1925) and "The Fiend with Twenty Faces" (1936),[14] blurred the lines between reality and fantasy, setting a precedent for future generations of Japanese speculative fiction writers.

Post-World War II boom

[edit]Following World War II, Japanese speculative fiction experienced a significant boom,[14] with authors exploring themes of post-apocalyptic landscapes, technological advancements, and the repercussions of war. Notable authors during this period include Yasutaka Tsutsui, known for his satirical and thought-provoking tales, and Kobo Abe, whose existentialist novels often delved into the human condition within surreal settings.[15]

Contemporary trends

[edit]In contemporary Japanese speculative fiction, themes of artificial intelligence, genetic engineering, and environmental degradation are prevalent, reflecting the anxieties and realities of the modern world.[16] Writers like Haruki Murakami have garnered international acclaim for their fusion of magical realism with speculative elements,[15] creating narratives that blur the boundaries between the ordinary and the extraordinary.

Japanese horror

[edit]Belief in ghosts, demons and spirits has been deep-rooted in Japanese folklore throughout history. It is entwined with mythology and superstition derived from Japanese Shinto, as well as Buddhism and Taoism brought to Japan from China and India. Stories and legends, combined with mythology, have been collected over the years by various cultures of the world, both past and present. Folklore has evolved in order to explain or rationalize various natural events. Inexplicable phenomena arouse a fear in humankind because there is no way for us to anticipate them or to understand their origins.[17] The early horror stories of Japan (also known as Kaidan or more recently J-Horror) revolved around vengeful spirits or Yūrei. In recent years, interest in these tales have been revived with the release of such films as Ju-on: The Grudge and Ring .[18][citation needed]

Japanese science fiction and fantasy

[edit]Japanese fiction has assumed a position of significance in many genres of world literature as it continues to chart its own creative course. Whereas science fiction in the English-speaking world developed gradually over a period of evolutionary change in style and content, SF in Japan took off from a very different starting line. Starting in the 1950s and 1960s, Japanese SF writers worked to combine their own thousand-year-old literary tradition with a flood of Western SF and other fiction. Contemporary Japanese SF thus began in a jumble of ideas and periods, and ultimately propelled Japanese authors into a quantum leap of development, rather than a steady process of evolution.

See also

[edit]Chinese science fiction and fantasy

[edit]Chinese American speculative fiction

[edit]

Many speculative works by Asian American authors delve into the immigrant experience, addressing themes of displacement, assimilation, and the search for belonging in a new land. Like speculative fiction in general, Chinese American speculative fiction often serves as a platform for social commentary. It may address current issues such as racism, discrimination, environmental degradation, and political unrest through the lens of speculative elements.[19]

One notable Asian American speculative fiction author is Ted Chiang, who is especially known for his short stories. His 1998 short story "Story of Your Life" is the basis for the 2016 film Arrival, which tells the story of a linguist who tries to decipher an alien language, and as she does so, her perception of time is profoundly altered.[20]

Chiang is the winner of numerous Hugo, Locus, and Nebula awards. He was born in Port Jefferson, New York, and his parents are immigrants from China.[21] Chiang refers to himself as an "occasional writer" and doesn't feel the need to write constantly or prolifically. His goal as a writer is to engage in philosophical thought experiments and try to work out the implications of various concepts.[22] He has said that he won't start writing a story until he knows how it's going to end,[23] and actually spent five years researching linguistics before feeling prepared to write "Story of Your Life."[24]

Chinese American author, Ken Liu, was born in China but immigrated to the US at age 11, has not only translated numerous Chinese science fiction novels into English, (including Three Body Problem by Liu Cixin, which became the first Asian novel to with the Hugo Award for Best Novel in 2015[25]), but has also won the Hugo, Nebula, Locus and other awards for his short stories and novels.[26]

When translating Chinese works to English, Liu has said that it can be difficult trying to translate the historical references and literary allusions that Chinese works are filled with. Unless a reader was fluent in Chinese culture, most of these references would not be easily understood.[27]

Liu has coined his own sub-genre mix of ancient Chinese legend and western fantasy as "silkpunk." This can be read in several of his novels such as The Grace of Kings and The Wall of Storms.[28]

Chinese American speculative fiction written by and about women

[edit]Chinese American speculative fiction written by and about women work on creating the feeling of nostalgia in readers, focusing in on experiences by second-generation Americans.[29] Women's experiences are also explored through the lens of cyberpunk fiction, with an emphasis on the female body.[11]

Texts written by female authors place women in the lead in previously male-dominated spaces, bringing about themes of empowerment.[11] These Chinese American fiction texts pull from the past, invoking the feeling of nostalgia in readers.[29] Novels such as Salt Fish Girl by Larissa Lai, may also pull from Chinese mythology in their works.[11] It is common for varying forms of privilege to be discussed and to examine the myriad of ways in which it affects those who have it versus those who do not.[29]

History is also largely taken into account in these texts from when people first immigrated from China to the United States.[29] Chinese American fiction texts then often give the perspectives of second-generation Americans and how their experiences affect both daily and family life, pulling from historical influences or personal experience.[29] Issues surrounding race are prominent and examined in these texts, both through metaphor and explicit statements.[11]

With the novel Severance by Ling Ma as a guide, other themes can be found of transformation, including that of both people and landscapes.[29] Common themes in this text and others, focus on the ways that corporations determine societal norms and expectations, and the effect that has on the individual.[11]

A sub-genre of some Chinese American speculative fiction texts can be described as cyberpunk, in which an emphasis is placed onto technology.[11] Reproductive rights are another common theme and issue, often discussed through a cyberpunk lens.[11] In texts centering women, the clone is discussed as a metaphor for the female body.[11] Female Chinese American authors in speculative fiction may discuss varying issues surrounding sexuality of the female body and the way it is seen and used in corporate society, utilizing the previously mentioned common themes.[11]

Indian speculative fiction

[edit]

Indian speculative fiction has had long-standing roots with the earliest known examples being published in 1835. Early authors such as Henry Meredith Parker, Henry Goodeve, Kylas Chunder Dutt, Soshee Chunder Dutt, Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain, and Jagadish Chandra Bose helped develop the genre.[30] From "The Junction of the Ocean: A Tale of the Year 2098", a story of how the construction of the Panama Canal changed the landscape of the world[31] to "The Republic of Orissá; A Page from the Annals of the Twentieth Century”, a dystopia about a revolt against Britain's institutionalization of a law supporting slavery on colonial India,[32] and "Sultana's Dream", a feminist utopia in where traditional gender norms are turned on their head,[33] as well as, "Runaway Cyclone", about a man who calmed a sea storm using hair oil, which anticipated the phenomenon known as the "butterfly effect,"[34] these authors' contributions bring unique perspectives on imperial and anti-imperial sentiments during colonial times.[30]

Contemporary examples of speculative fiction from an Indian perspective include Anil Menon's 2009 debut novel The Beast With Nine Billion Feet set in India in 2040 about two siblings who deal with their father's legacy by joining forces with another sibling duo from Sweden,[35] Vandana Singh's 2018 short story collection Ambiguity Machines and Other Stories which include stories like that of a poet from the eleventh century suddenly waking up in a futuristic spaceship as an AI and an unassuming woman with the ability to see the past,[36] and The Gollancz Book of South Asian Science Fiction, which are anthologies of Indian science fiction stories from various authors with two volumes currently out published in 2019 and 2021 respectively. They feature stories from the previously mentioned authors and many more. Some of these include stories about Karachi losing its sea, Gandhi reappearing in the present times, and aliens appearing on the railways of Uttar Pradesh.[37] With their twists on the genre, these stories present a different take for readers to appreciate.[38]

See also

[edit]Thai science fiction and fantasy

[edit]Caribbean speculative fiction writers of note

[edit]- Ángel Arango

- R.S.A Garcia

- Tobias Buckell

- Daína Chaviano

- Nalo Hopkinson

- Oscar Hurtado

- Marlon James[39]

- Karen Lord

- Baptiste, Tracey

See also:

South American speculative fiction writers of note

[edit]Latino/Latinx speculative fiction

[edit]This section may incorporate text from a large language model. (September 2024) |

The rise of Latino/Latinx speculative fiction offers a powerful platform for exploring complex themes and issues relevant to the Latinx community. By infusing elements of speculative fiction—such as science fiction, fantasy, and magical realism—with Latinx cultural motifs and narratives, authors are able to delve into pressing social, political, and cultural concerns in imaginative and thought-provoking ways. In her memoir In the Dream House, Carmen Maria Machado employs speculative fiction to discuss an abusive relationship. Machado notes, “in many cases we need more than reality to accurately describe reality.”[40]

Adam Silvera's They Both Die at the End, presents a noteworthy exploration of bisexuality, particularly through the contrast between Mateo and Rufus.[41] While Mateo's queerness is not explicitly labeled, Rufus's bisexuality is portrayed in a matter-of-fact manner throughout the narrative. The absence of explicit acknowledgment of Mateo's sexual identity raises questions about effective representation, as suggested by Jennifer Colette. However, the novel's portrayal of Rufus, who has already embraced his bisexuality as an integral part of his Latinidad, offers a nuanced intervention into discussions of queer identity within Latinx communities. Silvera's depiction of Rufus aligns with Lázaro Lima's proposition that queer identity practices can provide alternative social imaginaries, bridging past, present, and future experiences. By presenting Rufus's acceptance of his queerness as a part of his Latinidad, Silvera contributes to unraveling the complexities of Latinx queer experiences, offering a valuable perspective that enriches discussions of identity and representation in literature.

Latinx Authors contributions to speculative fiction

[edit]U.S.-based Latinx authors use speculative fiction to depict the experiences and struggles their communities face with the United States, including issues of prejudice, discrimination, marginalization, gentrification, and displacement. In his story "Monstro," Junot Diaz uses a pandemic to discuss social class and colonialism in the Caribbean. In his story "Room for Rent," Richie Narvaez uses a story about extraterrestrials coming to Earth and looking for a place to live to examine issues of colonialism and immigration. Author Ana Castillo touches on topics such as displacement and spirituality in her short story “Cowboy Medium.” As one of the characters in this story, Hawk tries to navigate his gift of spirituality to see beyond and the integration of newcomers changing the environment of the town.[42]

Latino American authors contributions to speculative fiction

[edit]Authors from Latin America are use speculative fiction to examine reality. For instance, Rodrigo Bastidad, co-founder of the independent publisher Vestigo, explains, “People do not have time to think about the future because they are too busy surviving the present."[43] As many authors want to envision a prosperous future in their writing many focus on the chaos that is happening currently. Colombian author Luis Carlos Barragan also emphasizes appropriating the future.[43] Authors are taking control of their narrative creating their own world filled with powerful beings and a country that thrives through chaos. Although these worlds have some futuristic aspects to them, they very much mirror current events. Latin American authors have the ability to rewrite the future in their work to change the story of their culture.

Chicano futurism

[edit]Chicano futurism has witnessed a surge in popularity in recent years. A prevalent theme within Chicano futurism is the connection of indigenous past to a place-rooted present, envisioning imagined futures, and the dwelling of syncretic gods. These narratives serve as vital threads, resonating like entangled particles of ancestors and descendants, offering boundless possibilities rooted in Latinx identity. These stories intertwine diverse cultural elements, offering a nuanced portrayal of Latinx identity and its potential trajectories. In doing so, U.S. Latino speculative fiction not only entertains but also provokes thought and reflection on the intricate layers of history, culture, and identity.[42] For example, Smoking Mirror Blues, by Ernest Hogan, delves deeply into the complexities of Western rationalism, which is deeply entrenched in the patriarchal history of modernity and colonialism.

Other topics in Latino/Latinx speculative fiction

[edit]Latino Speculative Fiction encompasses many current events and how authors get inspiration from their own experiences and experiences from what is going on in the world with this specific community. Latino Futurism might have to do with many things that are happening today in the Latin community. Too Mexican for the white community and too white for the Mexican community, issues with immigration, issues with the sexist machismo culture that is present in the Latin community with individuals wanting to find themselves. A novel that has all of this and a great coming of age story is a novel called, Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe. This is one example of as well as many that have shown a representation of current events with storytelling.[44]

This type of futurism may not always be invited with open arms by others. With many current events that are attacking the LGBTQ+ community and Latino/Latinx community. These stories of wanting to belong in a community of people can be seen in connection of wanting to belong in today's world. With many struggles in the LGBTQ community and Latino community. there are many in connection with literature and book that have to do with this. Such as Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe. [45]

Native American speculative fiction

[edit]Two-Spirit speculative fiction

[edit]

Two-Spirit speculative fiction is a genre that explores gender identity and cultural perspectives through Indigenous traditions and futuristic or alternate realities. The genre offers Indigenous authors and readers a chance to express, reclaim, and reshape their narratives while questioning conventional views on gender and culture through fictional stories.[46] The emergence of Two-Spirit speculative fiction can be understood in the context of queer literature's broader landscape. This includes its efforts to challenge heteronormative narratives and enhance representation within the LGBTQ+ community.

The term 'Two-Spirit' refers to transgender or non-binary individuals from Indigenous and Native American tribes. It was coined in 1990 by Indigiqueer/Two-Spirit people to replace the term 'berdache,' which marginalized those with non-traditional gender and sexual identities in Indigenous communities.[47]

The concept of "two-spirit" identity can affirm sovereignty by representing a modern interpretation of a traditional aspect of Native American heritage. Although the term serves as a catch-all, some Indigenous communities or tribes have their own specific terms for third-gender or non-binary gender roles.[48]

Queer identity

[edit]

Throughout history and into the present day, colonialism in the Western world has often erased or marginalized Indigenous identities. This erasure and replacement included views on queer identities, where men and women were expected to conform to specific and narrow gender roles within societal constraints.

In numerous indigenous tribes, the term "two-spirit" connotes a person who embodies both male and female archetypes or "spirits", resulting in a balance or mixture of gender expression.[49]

Two-Spirit literature

[edit]Two-Spirit speculative literature delves into the intersection of identity, culture, and queerness, and can inspire and empower readers to explore these aspects in their own lives. Often these works attempt to imagine futures and worlds, either in reality or fantastical, in which colonialism may have never happened or happened differently with varying outcomes. Two-Spirit literature is characterized by a sense of optimism and hope for the future, contrasting with the dark history of Indigenous peoples in the Americas, marked by destruction and genocide.[50]

Recognition of Two-Spirit literature and media by the wider literary community—including both academic review and mainstream audiences—offers Indigenous queer creators a platform to share their stories and experiences, addressing their frequent marginalization in mainstream media. Monica Martinez[51] says, ""Current conceptions of queerness equate queer with white, and actively work to harm Indigenous queer - "Indigiqueer" - and Two-Spirit identities that defy Western labels." In other words, associating queerness largely or solely with white experiences erases the unique struggles and life experiences of indigenous queer individuals.

Examples of Two-Spirit literature

[edit]- Love after the End: An Anthology of Two-Spirit and Indigiqueer Speculative Fiction by Joshua Whitehead

- Asegi Stories: Cherokee Queer and Two-Spirit Memory by Qwo-Li Driskill

- Jonny Appleseed by Joshua Whitehead

- To Shape a Dragon's Breath by Moniquill Blackgoose

- Elatsoe by Darcie Little Badger

- Mohawk Trail by Beth Brant

- Kiss of the Fur Queen by Tomson Highway

- Drowning in Fire by Craig S. Womack

Two Spirit speculative fiction and decolonization

[edit]Speculative fiction has been a vital medium for Two-Spirit authors to express their creativity and connect with readers through their stories. These stories often explore the concept of utopia, where people live in ideal worlds beyond the limits of our current reality. Two-Spirit authors use their writing to assert their independence from settler counter-parts and envision a better future for themselves and their communities.[citation needed]

Through their writing, these authors shed light on the harsh realities that queer indigenous people face in modern times, including systemic oppression, loss of native language, and cultural and sexual identity. They use their stories to break away from the colonial way of thinking about sex, gender, and cultural identity, and instead offer a unique perspective that challenge the social norms that were implemented by colonial settlers.[citation needed]

By imagining worlds where people live on other planets, dimensions, and realities in both the past and present, Two-Spirit authors allow readers to explore the endless possibilities of the human experience.[citation needed]

Two-Spirit media

[edit]Speculative media created by Two-Spirit individuals is characterized by its ability to challenge existing power structures and norms, as well as to envision and create new possibilities for gender and cultural identities. There, of course, is an on-going relationship between written and audio/visual media within the Two-Spirit community, and themes and adaptations exist between them.

Examples of Two-Spirit media

[edit]- "Drunktown's Finest" by Sydney Freeland

- "Two Spirits" by Lydia Nibley

List of Native authors of note

[edit]- Sherman Alexie

- Winfred Blevins

- Louise Erdrich

- Stephen Graham Jones

- Daniel Heath Justice

- Susan Power

- Rebecca Roanhorse

- William Sanders (writer)

- Greg Sarris

- Leslie Marmon Silko (non-enrolled Laguna Pueblo descendant)

- Cynthia Leitich Smith

- Martin Cruz Smith

- Craig Strete

- Gerald Vizenor

Asian diaspora speculative fiction writers of note

[edit]- Aliette de Bodard

- Ted Chiang

- Wesley Chu

- Larissa Lai

- Fonda Lee

- Ken Liu

- Marjorie Liu

- Malinda Lo

- Marie Lu

- Mary Anne Mohanraj

- Vandana Singh

- Alyssa Wong

- Laurence Yep

- Charles Yu

- Kat Zhang

Anglo-Indian speculative fiction writers

[edit]See also

[edit]Further reading

[edit]- hooks, bell (1999). Yearning: Race, Gender, and Cultural Politics. Boston: South End Press.

- Bogle, Donald (2001). Toms, Coons, Mulattoes, Mammies, and Bucks: An Interpretive History of Blacks in American Films (4th ed.). New York: Bloomsbury.

- Carrington, André M. (2016). Speculative Blackness: The Future of Race in Science Fiction. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

References

[edit]- ^ Wabuke, Hope (27 August 2020). "Afrofuturism, Africanfuturism, and the Language of Black Speculative Literature". LA Review of Books. Archived from the original on 29 August 2020. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- ^ Alter, Alexandra (29 May 2016). "Middle Eastern Writers Find Refuge in the Dystopian Novel". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 8 April 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p El Shakry, Hoda (4 July 2021). "Palestine and the Aesthetics of the Future Impossible". Interventions. 23 (5): 669–690. doi:10.1080/1369801X.2021.1885471. ISSN 1369-801X.

- ^ a b c d Marusek, Sarah (20 October 2022). "Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow: social justice and the rise of dystopian art and literature post-Arab Uprisings". British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies. 49 (5): 747–768. doi:10.1080/13530194.2020.1853504. ISSN 1353-0194.

- ^ Michalak-Pikulska, Barbara; Gadomski, Sebastian (30 November 2022). "The Beginnings of Egyptian Science Fiction Literature". Studia Litteraria. 17 (3): 227–239. doi:10.4467/20843933ST.22.019.16171.

- ^ Khaleeli, Homa (15 April 2010). "Nawal El Saadawi: Egypt's radical feminist". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 5 May 2024.

- ^ a b Salami, Minna (7 October 2015). "An Egyptian classic of feminist fiction". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 5 May 2024.

- ^ "Musings on Asianfuturism? – ED(MOND)CHANG(ED)AGOGY". 27 April 2020. Retrieved 27 April 2024.

- ^ "A Reflection on Chinese and Asian American Representation in Sci-Fi and Fantasy". Santa Fe Writers Project. Retrieved 27 April 2024.

- ^ Gullander-Drolet, Claire (2021). "Imperialist Nostalgia and Untranslatable Affect in Ling Ma's Severance". Science Fiction Studies. 48 (1): 94–108. doi:10.1353/sfs.2021.0024. ISSN 2327-6207.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Roh, David S.; Huang, Betsy; Niu, Greta A., eds. (2015). Techno-Orientalism: imagining Asia in speculative fiction, history, and media. Asian American studies today. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-7064-8.

- ^ Schnellbächer, Thomas (2002). "Has the Empire Sunk Yet? The Pacific in Japanese Science Fiction". Science Fiction Studies. 29 (3): 382–396. ISSN 0091-7729. JSTOR 4241106.

- ^ "Special Issue: Mixed Heritage Asian American Literature". MixedRaceStudies.org. Retrieved 18 April 2024.

- ^ a b "Musings on Asianfuturism? – ED(MOND)CHANG(ED)AGOGY". 27 April 2020. Retrieved 18 April 2024.

- ^ a b Fan, Christopher T. (5 November 2014). "Melancholy Transcendence: Ted Chiang and Asian American Postracial Form". Post45: Peer Reviewed. ISSN 2168-8206.

- ^ Cordasco, Rachel (2021). Out of This World: Speculative Fiction in Translation from the Cold War to the New Millennium. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 9780252052910.

- ^ Rubin, Norman A. (26 June 2000). "Ghosts, Demons and Spirits in Japanese Lore". Asianart.com.

- ^ Orenstein, C. & Cusack, T. (2024). Puppet and spirit: Ritual, religion, and performing objects: Volume II. London: Routledge. DOI: 10.4324/9781003150589

- ^ Esaki, Brett J. (22 January 2020). "Ted Chiang's Asian American Amusement at Alien Arrival". Religions. 11 (2): 56. doi:10.3390/rel11020056. hdl:10150/641210.

- ^ Smith, Andy (3 January 2020). "Alien Worlds". Brown Alumni Magazine. Retrieved 27 April 2024.

- ^ "Ted Chiang". Penguin Random House. 25 April 2024. Retrieved 25 April 2024.

- ^ Rothman, Joshua (5 January 2017). "Ted Chiang's Soulful Science Fiction". The New Yorker. Retrieved 25 April 2024.

{{cite magazine}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Solomon, Avi (29 January 2014). "Stories of Ted Chiang's Life and Others". Medium. Retrieved 25 April 2024.

- ^ Ulaby, Neda (11 November 2016). "'Arrival' Author's Approach to Science Fiction? Slow, Steady and Successful". NPR. Retrieved 25 April 2024.

- ^ Alter, Alexandra (3 December 2019). "How Chinese Sci-Fi Conquered America". The New York Times. Retrieved 25 April 2024.

- ^ Liu, Ken (27 April 2024). "About". Ken Liu, Writer. Retrieved 27 April 2024.

- ^ Sullivan, Collin (20 August 2016). "Chinese SF and the Art of Translation - A Q&A With Ken Liu". Nature.com. Retrieved 27 April 2024.

- ^ Tonkin, Boyd (30 October 2016). "Meet the Man Bringing Chinese Science Fiction to the West". Newsweek. Retrieved 27 April 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Gullander-Drolet, Claire (2021). "Imperialist Nostalgia and Untranslatable Affect in Ling Ma's Severance". Science Fiction Studies. 48 (1): 94–108. doi:10.1353/sfs.2021.0024. ISSN 2327-6207.

- ^ a b "Science Fiction in Colonial India, 1835–1905". AnthemPress. Retrieved 26 April 2024.

- ^ Parker, Henry Meredith (1835). ""The Junction of the Ocean. A Tale of the Year 2098"". openpublishing.psu.edu. Retrieved 26 April 2024.

- ^ Dutt, Shoshee Chunder (1845). ""The Republic of Orissá; A Page from the Annals of the Twentieth Century"". openpublishing.psu.edu. Retrieved 26 April 2024.

- ^ "Sultana's Dream". digital.library.upenn.edu. Retrieved 26 April 2024.

- ^ words, Anil MenonBy: Vandana Singh Issue: 30 September 2013 1139 (30 September 2013). "Introduction to "Runaway Cyclone" and "Sheesha Ghat"". Strange Horizons. Retrieved 26 April 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "The Beast With Nine Billion Feet | Anil Menon". Retrieved 31 March 2024.

- ^ "Ambiguity Machines | Small Beer Press". Small Beer Press | Really rather good books. 13 February 2018. Retrieved 31 March 2024.

- ^ "The Gollancz Book of South Asian Science Fiction". Goodreads. Retrieved 31 March 2024.

- ^ "Perspective | Let's talk about wonderful Indian science-fiction and fantasy novels". Washington Post. 23 March 2021. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ "Marlon James's Next Book Will Be 'African Game Of Thrones'". Gizmodo. 12 December 2015. Retrieved 15 February 2023.

- ^ Stefanakou, Athena (14 June 2023). "The (Un)Reality of Abuse in Carmen Maria Machado's In the Dream House". Leiden Elective Academic Periodical (3). Retrieved 24 October 2024.

- ^ Boffone, Trevor (19 April 2022). "When Bisexuality Is Spoken: Normalizing Bi Latino Boys in Adam Silvera's They Both Die At the End". Research on Diversity in Youth Literature. 4 (2). doi:10.21900/j.rydl.v4i2.1593.

- ^ a b Castillo, Ana (2020). Latinx Rising: An Anthology of Latinx Science Fiction and Fantasy. Matthew David Goodwin (published June 2020). p. 60. ISBN 978-0-8142-7798-0.

- ^ a b Hart, Emily (10 June 2023). "Science Fiction From Latin America, With Zombie Dissidents and Aliens in the Amazon". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 8 April 2024.

- ^ Staff, Gateway (21 November 2022). "Latino Representation and Stereotypes in American Film and Television". Gateway. Retrieved 29 April 2024.

- ^ Abate, Michelle (10 June 2019). "Out of the Past: Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe, the AIDS Crisis, and Queer Retrosity". Research on Diversity in Youth Literature. 2 (1). doi:10.21900/j.rydl.v2i1.1539.

- ^ Pearson, Wendy Gay (19 October 2022), "Speculative Fiction and Queer Theory", Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication, doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.1214, ISBN 978-0-19-022861-3, retrieved 1 May 2024

- ^ Schmoll, E. Nastacia (2023). "Indigiqueer Reimaginings of Science Fiction". Swiss Papers in English Language and Literature (in German). 2023 (42): 175–193. doi:10.33675/SPELL/2023/42/14.

- ^ Waard, N. S. de (30 June 2021). "The Representation of Two-Spiritness in Contemporary Native American Poetry: Defining Two-Spiritness and Reclaiming Sovereignty".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Laing, Marie (2018). "Conversations with Young Two-Spirit, Trans and Queer Indigenous People About the Term Two-Spirit" (PDF). Ontario Institute for Studies in Education University of Toronto.

- ^ Elm, Jessica H. L.; Lewis, Jordan P.; Walters, Karina L.; Self, Jen M. (2016). ""I'm in this World for a Reason": Resilience and recovery among American Indian and Alaska Native Two Spirit Women". Journal of Lesbian Studies. 20 (3–4): 352–371. doi:10.1080/10894160.2016.1152813. ISSN 1089-4160. PMC 6424359. PMID 27254761.

- ^ Martinez, Monica (1 May 2022). "Decolonizing Queer Advocacy: Two-Spirit Futurisms and the Importance of Indigenous Speculative Fiction".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)