Cinema of South Korea

| Cinema of South Korea | |

|---|---|

Movie theater in Sincheon | |

| No. of screens | 3475 (2024)[1] |

| • Per capita | 5.3 per 100,000 (2015)[1] |

| Main distributors | CJ E&M (21%) NEW (18%) Lotte (15%)[2] |

| Produced feature films (2015)[3] | |

| Total | 269 |

| Number of admissions (2015)[4] | |

| Total | 217,300,000 |

| National films | 113,430,600 (52%) |

| Gross box office (2015)[4] | |

| Total | ₩1.59 trillion |

| National films | ₩830 billion (52%) |

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Korea |

|---|

| Society |

| Arts and literature |

| Other |

| Symbols |

|

South Korean films have been heavily influenced by such events and forces as the Korea under Japanese rule, the Korean War, government censorship, the business sector, globalization, and the democratization of South Korea.[5][6]

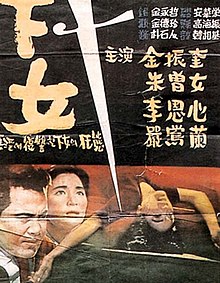

The golden age of South Korean cinema in the mid-20th century produced what are considered two of the best South Korean films of all time, The Housemaid (1960) and Obaltan (1961),[7] while the industry's revival with the Korean New Wave from the late 1990s to the present produced both of the country's highest-grossing films, The Admiral: Roaring Currents (2014) and Extreme Job (2019), as well as prize winners on the festival circuit including Golden Lion recipient Pietà (2012) and Palme d'Or recipient and Academy Award winner Parasite (2019) and international cult classics including Oldboy (2003),[8] Snowpiercer (2013),[9] and Train to Busan (2016).[10]

With the increasing global success and globalization of the Korean film industry, the past two decades have seen Korean actors like Lee Byung-hun and Bae Doona star in American films, Korean auteurs such as Park Chan-wook and Bong Joon-ho direct English-language works, Korean American actors crossover to star in Korean films as with Steven Yeun and Ma Dong-seok, and Korean films be remade in the United States, China, and other markets. The Busan International Film Festival has also grown to become Asia's largest and most important film festival.

American film studios have also set up local subsidiaries like Warner Bros. Korea and 20th Century Fox Korea to finance Korean films like The Age of Shadows (2016) and The Wailing (2016), putting them in direct competition with Korea's Big Four vertically integrated domestic film production and distribution companies: Lotte Cultureworks (formerly Lotte Entertainment), CJ Entertainment, Next Entertainment World (NEW), and Showbox. Netflix has also entered Korea as a film producer and distributor as part of both its international growth strategy in search of new markets and its drive to find new content for consumers in the U.S. market amid the "streaming wars" with Disney, which has a Korean subsidiary, and other competitors.

History

[edit]The earliest movie theaters in the country opened during the late Joseon to Korean Empire periods. The first was Ae Kwan Theater,[11] followed by Dansungsa.[12]

Liberation and war (1945–1953)

[edit]

With the surrender of Japan in 1945 and the subsequent liberation of Korea, freedom became the predominant theme in South Korean cinema in the late 1940s and early 1950s.[5] One of the most significant films from this era is director Choi In-gyu's Viva Freedom! (1946), which is notable for depicting the Korean independence movement. The film was a major commercial success because it tapped into the public's excitement about the country's recent liberation.[13]

However, during the Korean War, the South Korean film industry stagnated, and only 14 films were produced from 1950 to 1953. All of the films from that era have since been lost.[14] Following the Korean War armistice in 1953, South Korean president Syngman Rhee attempted to rejuvenate the film industry by exempting it from taxation. Additionally foreign aid arrived in the country after the war that provided South Korean filmmakers with equipment and technology to begin producing more films.[15]

Golden age (1955–1972)

[edit]

Though filmmakers were still subject to government censorship, South Korea experienced a golden age of cinema, mostly consisting of melodramas, starting in the mid-1950s.[5] The number of films made in South Korea increased from only 15 in 1954 to 111 in 1959.[16]

One of the most popular films of the era, director Lee Kyu-hwan's now lost remake of Chunhyang-jeon (1955), drew 10 percent of Seoul's population to movie theaters[15] However, while Chunhyang-jeon re-told a traditional Korean story, another popular film of the era, Han Hyung-mo's Madame Freedom (1956), told a modern story about female sexuality and Western values.[17]

South Korean filmmakers enjoyed a brief freedom from censorship in the early 1960s, between the administrations of Syngman Rhee and Park Chung Hee.[18] Kim Ki-young's The Housemaid (1960) and Yu Hyun-mok's Obaltan (1960), now considered among the best South Korean films ever made, were produced during this time.[7] Kang Dae-jin's The Coachman (1961) became the first South Korean film to win an award at an international film festival when it took home the Silver Bear Jury Prize at the 1961 Berlin International Film Festival.[19][20]

When Park Chung Hee became acting president in 1962, government control over the film industry increased substantially. Under the Motion Picture Law of 1962, a series of increasingly restrictive measures was enacted that limited imported films under a quota system. The new regulations also reduced the number of domestic film-production companies from 71 to 16 within a year. Government censorship targeted obscenity, communism, and unpatriotic themes in films.[21][22] Nonetheless, the Motion Picture Law's limit on imported films resulted in a boom of domestic films. South Korean filmmakers had to work quickly to meet public demand, and many films were shot in only a few weeks. During the 1960s, the most popular South Korean filmmakers released six to eight films per year. Notably, director Kim Soo-yong released ten films in 1967, including Mist, which is considered to be his greatest work.[19]

In 1967, South Korea's first animated feature film, Hong Kil-dong, was released. A handful of animated films followed including Golden Iron Man (1968), South Korea's first science-fiction animated film.[19]

Censorship and propaganda (1973–1979)

[edit]Government control of South Korea's film industry reached its height during the 1970s under President Park Chung Hee's authoritarian "Yusin System." The Korean Motion Picture Promotion Corporation was created in 1973, ostensibly to support and promote the South Korean film industry, but its primary purpose was to control the film industry and promote "politically correct" support for censorship and government ideals.[23] According to the 1981 International Film Guide, "No country has a stricter code of film censorship than South Korea – with the possible exception of the North Koreans and some other Communist bloc countries."[24]

Only filmmakers who had previously produced "ideologically sound" films and who were considered to be loyal to the government were allowed to release new films. Members of the film industry who tried to bypass censorship laws were blacklisted and sometimes imprisoned.[25] One such blacklisted filmmaker, the prolific director Shin Sang-ok, was kidnapped by the North Korean government in 1978 after the South Korean government revoked his film-making license in 1975.[26]

The propaganda-laden movies (or "policy films") produced in the 1970s were unpopular with audiences who had become accustomed to seeing real-life social issues onscreen during the 1950s and 1960s. In addition to government interference, South Korean filmmakers began losing their audience to television, and movie-theater attendance dropped by over 60 percent from 1969 to 1979.[27]

Films that were popular among audiences during this era include Yeong-ja's Heydays (1975) and Winter Woman (1977), both box office hits directed by Kim Ho-sun.[26] Yeong-ja's Heydays and Winter Women are classified as "hostess films," which are movies about prostitutes and bargirls. Despite their overt sexual content, the government allowed the films to be released, and the genre was extremely popular during the 1970s and 1980s.[22]

Recovery (1980–1996)

[edit]In the 1980s, the South Korean government began to relax its censorship and control of the film industry. The Motion Picture Law of 1984 allowed independent filmmakers to begin producing films, and the 1986 revision of the law allowed more films to be imported into South Korea.[21]

Meanwhile, South Korean films began reaching international audiences for the first time in a significant way. Director Im Kwon-taek's Mandala (1981) won the Grand Prix at the 1981 Hawaii Film Festival, and he soon became the first Korean director in years to have his films screened at European film festivals. His film Gilsoddeum (1986) was shown at the 36th Berlin International Film Festival, and actress Kang Soo-yeon won Best Actress at the 1987 Venice International Film Festival for her role in Im's film, The Surrogate Woman.[28]

In 1988, the South Korean government lifted all restrictions on foreign films, and American film companies began to set up offices in South Korea. In order for domestic films to compete, the government once again enforced a screen quota that required movie theaters to show domestic films for at least 146 days per year. However, despite the quota, the market share of domestic films was only 16 percent by 1993.[21]

The South Korean film industry was once again changed in 1992 with Kim Ui-seok's hit film Marriage Story, released by Samsung. It was the first South Korean movie to be released by business conglomerate known as a chaebol, and it paved the way for other chaebols to enter the film industry, using an integrated system of financing, producing, and distributing films.[29]

It is important to note that until 1996, when the Film Promotion Law was passed,[30] the film industry was still subject to censorship. Censoring of scripts in pre-production was officially dismissed in the late 1980s, still producers were unofficially expected to present two copies to the Public Performance Ethics Committee,[31] who had the power to modify by completely cutting scenes.[32]

Renaissance (1997–present)

[edit]As a result of the 1997 Asian financial crisis, many chaebols began to scale back their involvement in the film industry. However, they had already laid the groundwork for a renaissance in South Korean film-making by supporting young directors and introducing good business practices into the industry.[29] "New Korean Cinema," including glossy blockbusters and creative genre films, began to emerge in the late 1990s and 2000s.[6] At the same time, representation of women in visual media drastically declined in the aftermath of the 1997 IMF Crisis.[33]

South Korean cinema saw domestic box-office success exceeding that of Hollywood films in the late 1990s largely due to screen quota laws that limited the public showing foreign films.[34] First enacted in 1967, South Korea's screen quota placed restrictions on the number of days per year that foreign films could be shown at any given theater—garnering criticism from film distributors outside South Korea as unfair. As a prerequisite for negotiations with the United States for a free-trade agreement, the Korean government cut its annual screen quota for domestic films from 146 days to 73 (allowing more foreign films to enter the market).[35] In February 2006, South Korean movie workers responded to the reduction by staging mass rallies in protest.[36] According to Kim Hyun, "South Korea's movie industry, like that of most countries, is grossly overshadowed by Hollywood. The nation exported US$2 million-worth of movies to the United States last year and imported $35.9 million-worth".[37]

One of the first blockbusters was Kang Je-gyu's Shiri (1999), a film about a North Korean spy in Seoul. It was the first film in South Korean history to sell more than two million tickets in Seoul alone.[38] Shiri was followed by other blockbusters including Park Chan-wook's Joint Security Area (2000), Kwak Jae-yong's My Sassy Girl (2001), Kwak Kyung-taek's Friend (2001), Kang Woo-suk's Silmido (2003), and Kang Je-gyu's Taegukgi (2004). In fact, both Silmido and Taegukgi were seen by 10 million people domestically—about one-quarter of South Korea's entire population.[39]

South Korean films began attracting significant international attention in the 2000s, due in part to filmmaker Park Chan-wook, whose movie Oldboy (2003) won the Grand Prix at the 2004 Cannes Film Festival and was praised by American directors including Quentin Tarantino and Spike Lee, the latter of whom directed the remake Oldboy (2013).[8][40]

Director Bong Joon-ho's The Host (2006) and later the English-language film Snowpiercer (2013), are among the highest-grossing films of all time in South Korea and were praised by foreign film critics.[41][9][42] Yeon Sang-ho's Train to Busan (2016), also one of the highest-grossing films of all time in South Korea, became the second highest-grossing film in Hong Kong in 2016.[43]

In 2019, Bong Joon-ho's Parasite became the first film from South Korea to win the prestigious Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival.[44] At the 92nd Academy Awards, Parasite became the first South Korean film to receive any sort of Academy Awards recognition, receiving six nominations. It won Best Picture, Best Director, Best International Feature Film and Best Original Screenplay, becoming the first film produced entirely by an Asian country to receive a nomination for the Academy Award for Best Picture since Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, as well as the first film not in English ever to win the Oscar for Best Picture.[45]

LGBTQ cinema

[edit]LGBTQ films and representations of LGBTQ characters in South Korean cinema can be seen since the beginning of South Korean cinema despite public perceptions of South Korea as being largely anti-LGBT. Defining "queer cinema" has been up for debate by critics of cinema because of the difficulties in defining "queer" in film contexts. The term "queer" has its roots in the English language and although its origins held negative connotations, reclamation of the term began in the 1980s in the U.S. and has come to encompass non-heteronormative sexualities even outside of the U.S.[46] Thus, queer cinema in South Korea can be thought of as encompassing depictions of non-heteronormative sexualities. On this note, LGBTQ and queer have been used interchangeably by critics of South Korean cinema.[47] While the characteristics that constitute a film as LGBTQ can be subjective due to defining the term "queer" as well as how explicit or implicit LGBTQ representation is in a film, there are a number of films that have been considered as such in Korean cinema.

According to Pil Ho Kim, Korean queer cinema can be categorized into three different categories regarding visibility and public reception. There is the Invisible Age (1945–1997), where films with queer themes have received limited attention as well as discrete representations due to societal pressures, the Camouflage Age (1998–2004) characterized by a more liberal political and social sphere that encouraged filmmakers to increase production of LGBTQ films and experiment more with their overt depictions but still remaining hesitant, and finally, the Blockbuster Age (2005–present) where LGBTQ themed films began to enter the mainstream following the push against censorship by independent films prior.[48]

Though queer Korean cinema has mainly been represented through independent films and short films, there exists a push for the inclusion of LGBTQ representation in the cinema as well as a call for attention to these films. Turning points include the dismantling of the much stricter Korean Performing Arts Ethics Committee and the emergence of the Korean Council for Performing Arts Promotions and the "Seoul Queer Film and Video Festival" in 1998 after the original gay and lesbian film festival was shut down by Korean authorities.[49] The Korea Queer Film Festival, part of the Korea Queer Culture Festival, has also pushed for visibility of queer Korean films.

LGBTQ films by openly LGBTQ directors

[edit]LGBTQ films by openly LGBTQ identifying directors have historically been released independently, with a majority of them being short films. The films listed reflect such films and reveal how diverse the representations can be.

- Everyday is Like Sunday (Lee Song Hee-il 1997): The independent, short film directed by openly-LGBTQ identifying Lee Hee-il follows two male characters who meet then become separated, with direct representation of their relationship as homosexual. The independent aspect of the film may have had a role in allowing for a more obvious representation of homosexuality since there is less pressure for appealing to a mainstream audience and does not require government sponsorship.[49]

- No Regret (Lee Song Hee-il, 2006): An independent film co-directed by Lee Hee-il and Kim-Cho Kwang-su, both of whom had ties to the gay activist group Ch'in'gusai, portrays LGBTQ characters in a way that normalizes their identities.[48] The film was also able to see more success than usual for independent films for its marketing strategy that targeted a primarily female audience with an interest in what is known as Boys' Love.[48][50]

- Boy Meets Boy (Kimjo Kwang-soo, 2008): Claimed by the director to be inspired by their own personal experience, the independent short film tells an optimistic story of two men, with the possibility of mutual feelings of attraction after a brief encounter.[51] Even though there is homosexual attraction, it is told through a heterosexual lens, since the masculinity of one character and the femininity of the other are in contrast with each other, creating ambiguity about their queerness due in part to homophobia in society and the political climate.[50]

- Just Friends? (Kimjo Kwang-soo, 2009): This independent short film by Kimjo Kwang-soo, also written as Kim Cho Kwang-soo, represents LGBTQ characters, with the main character, Min-soo, having to deal with his mother's disapproval of his relationship with another male character. This short film, like Boy Meets Boy also offers a more optimistic ending.[52]

- Stateless Things (Kim Kyung-mook, 2011): In the film, both LGBT characters and Korean-Chinese immigrant workers are considered non-normative and are marginalized.[47] The film can be considered to have a queer point-of-view in the sense that it has an experimental quality that creates ambiguity when it comes to non-normative themes. However, the film does depict graphic, homoeroticism, making the representation of homosexuality clear.[53]

LGBTQ films not by openly LGBTQ directors

[edit]- The Pollen of Flowers (Ha Gil-jong, 1972): Regarded as the first gay Korean film by the director's brother Ha Myong-jung, the film depicts homosexuality in the film through tension in LGBTQ relationships though it was not typically regarded as a queer film at the time of release.[48] The film's political message and critique of the president at the time, Park Chung Hee, may be the reason that queer relationships were overshadowed.[54] In spite of being an earlier Korean film depicting homosexuality, the film is more explicit in these relationships than might be expected at the time.[54]

- Ascetic: Woman and Woman (Kim Su-hyeong, 1976): Though the film was given award-winning status by the Korean press, during the time of the release, Ascetic remained an under-recognized film by the public.[49] The film is seen as the first lesbian film by Korean magazine Buddy and tells the story of two women who develop feelings for each other.[48] Though the homosexual feelings between the women are implied through "thinly-veiled sex acts" that could be more explicit, it was considered homosexual given the context of the heavy censorship regulations of the 1970s.[48] Despite the film's status as a lesbian film, it has been noted that the director did not intend to make an LGBTQ film, but rather a feminist film by emphasizing the meaningfulness of the two women's interactions and relationships. Even so, Kim Su-hyeong has said the film can be seen as both lesbian and feminist.[49]

- Road Movie (Kim In-shik, 2002): Even though the film was released through a large distribution company, the film did not reach the expected mainstream box office success, yet it is still seen as a precursor to queer blockbuster films to come.[48] The film is explicit in its homosexual content[50] and portrays a complicated love triangle between two men and a woman while focusing primarily on a character who is homosexual.[50] It is noteworthy that Road Movie is one of the few full-length feature films in South Korea to revolve around a queer main character.[50]

- The King and the Clown (Lee Joon-ik, 2005): The King and the Clown is seen as having a major impact in queer cinema for its great mainstream success. In the film, one of the characters is seen as representing queer-ness through his embodiment of femininity, which is often regarded as the character trope of the "flower boy" or kkonminam.[48] However, actual depictions of homosexuality are limited and are depicted only through a kiss.[48] The King and the Clown is seen as influential because of its representation of suggested gay characters that preceded other queer films to come after it.[50] The film depicts undertones of a love triangle between two jesters and a king and suggests homosexuality in a pre-modern time period (Joseon Dynasty)[50] and is based on the play Yi (2000) which drew on the passage The Annals of the Choseon Dynasty, two pieces that were more explicit in their homosexuality in comparison the film.[50] The representation of gay intimacy and attraction remains ambiguous in the film and has been criticized by the LGBT community for its portrayal of queerness.[50]

- Frozen Flower (Yoo Ha, 2008): A Frozen Flower followed other queer films such as The King and the Clown, Broken Branches, and Road Movie.[47] This film reached a mainstream audience which may have been due in part to a well-received actor playing a homosexual character. Critiques of the film have questioned the character Hong Lim's homosexuality, however, it may be suggested that his character is actually bisexual.[55] Despite the explicit homosexual/queer love scenes in the film that brought a shock to mainstream audiences,[55] the film still managed to be successful and expose a large audience to a story about queer relationships.[47]

- The Handmaiden (Park Chan-wook, 2016): The film is a cross-cultural adaptation of the lesbian novel Fingersmith written by Sarah Waters.[56] The Handmaiden includes representation of lesbian characters who are seen expressing romantic feelings towards each other in a sensual way that has been critiqued as voyeuristic for its fetishization of the female body.[57] Explicitly depicting the homosexual attraction of the characters Sook-hee and Lady Hideko is a bath scene where the act of filing down the other's tooth has underlying sexual tension.[57] The film had mainstream box-office success and "over the first six weeks of play [reached a gross] of £1.25 million".[57]

Horror Cinema

[edit]Korean horror entered its first fertile period in the 1960s.[58] Modern South Korean horror films are typically distinguished by stylish directing, themes of social commentary, and genre blending.[59] Horror films are designed to 'cool' the audience; traditionally, horror films are screened domestically during the summer months, as they are thought to be effective at lowering body temperature by providing 'chills'.[58]

Highest-grossing films

[edit]The Korean Film Council has published box office data on South Korean films since 2004. As of March 2021, the top ten highest-grossing domestic films in South Korea since 2004 are as follows.[41]

- The Admiral: Roaring Currents (2014)

- Extreme Job (2019)

- Along with the Gods: The Two Worlds (2017)

- Ode to My Father (2014)

- Veteran (2015)

- The Thieves (2012)

- Miracle in Cell No.7 (2013)

- Assassination (2015)

- Masquerade (2012)

- Along with the Gods: The Last 49 Days (2018)

Film awards

[edit]South Korea's first film awards ceremonies were established in the 1950s, but have since been discontinued. The longest-running and most popular film awards ceremonies are the Grand Bell Awards, which were established in 1962, and the Blue Dragon Film Awards, which were established in 1963. Other awards ceremonies include the Baeksang Arts Awards, the Korean Association of Film Critics Awards, and the Busan Film Critics Awards.[60]

Film festivals

[edit]In South Korea

[edit]Founded in 1996, the Busan International Film Festival is South Korea's major film festival and has grown to become one of the largest and most prestigious film events in Asia.[61]

South Korea at international festivals

[edit]The first South Korean film to win an award at an international film festival was Kang Dae-jin's The Coachman (1961), which was awarded the Silver Bear Jury Prize at the 1961 Berlin International Film Festival.[19][20] The tables below list South Korean films that have since won major international film festival prizes.

| Year | Award | Film | Recipient[63] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1961 | Silver Bear Extraordinary Jury Prize | The Coachman | Kang Dae-jin |

| 1962 | Silver Bear Extraordinary Jury Prize | To the Last Day | Shin Sang-ok |

| 1994 | Alfred Bauer Prize | Hwa-Om-Kyung | Jang Sun-woo |

| 2004 | Silver Bear for Best Director | Samaritan Girl | Kim Ki-duk |

| 2005 | Honorary Golden Bear | — | Im Kwon-taek |

| 2007 | Alfred Bauer Prize | I'm a Cyborg, But That's OK | Park Chan-wook |

| 2011 | Golden Bear for Best Short Film | Night Fishing | Park Chan-wook, Park Chan-kyong |

| Silver Bear for Best Short Film | Broken Night | Yang Hyo-joo | |

| 2017 | Silver Bear for Best Actress | On the Beach at Night Alone | Kim Min-hee |

| 2020 | Silver Bear for Best Director | The Woman Who Ran | Hong Sang-soo |

| 2021 | Silver Bear for Best Screenplay | Introduction | Hong Sang-soo |

| Year | Award | Film | Recipient[64] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | Best Director | Chi-hwa-seon | Im Kwon-taek |

| 2004 | Grand Prix | Oldboy | Park Chan-wook |

| 2007 | Best Actress | Secret Sunshine | Jeon Do-yeon |

| 2009 | Prix du Jury | Thirst | Park Chan-wook |

| 2010 | Best Screenplay Award | Poetry | Lee Chang-dong |

| Prix Un Certain Regard | Hahaha | Hong Sang-soo | |

| 2011 | Arirang | Kim Ki-duk | |

| 2013 | Short Film Palme d'Or | Safe | Moon Byoung-gon |

| 2019 | Palme d'Or | Parasite | Bong Joon-ho |

| 2022 | Best Director | Decision to Leave | Park Chan-wook |

| Year | Award | Film | Recipient[65] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1987 | Best Actress | The Surrogate Woman | Kang Soo-yeon |

| 2002 | Silver Lion | Oasis | Lee Chang-dong |

| 2004 | 3-Iron | Kim Ki-duk | |

| 2012 | Golden Lion | Pietà |

| Year | Award | Film | Recipient[66] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | Grolsch People's Choice Award 2nd Runner-Up | Parasite | Bong Joon-ho |

| Year | Award | Film | Recipient[67] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | Freedom of Expression Award | Repatriation | Kim Dong-won |

| 2013 | World Cinema Grand Jury Prize: Dramatic | Jiseul | O Muel |

| Year | Award | Film | Recipient[68] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | Silver Medallion | N/A | Im Kwon-taek |

| Year | Award | Film | Recipient[69] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1987 | FIPRESCI Prize | The Man with Three Coffins | Lee Jang-ho |

| 1992 | Grand Prix | White Badge | Chung Ji-young |

| Best Director | |||

| 1998 | Gold Award | Spring in My Hometown | Lee Kwang-mo |

| 1999 | Special Jury Prize | Rainbow Trout | Park Jong-won |

| 2000 | Special Jury Prize | Virgin Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors | Hong Sang-soo |

| Asian Film Award - Special Mention | |||

| 2001 | Best Artistic Contribution Award | One Fine Spring Day | Hur Jin-ho |

| 2003 | Asian Film Award | Memories of Murder | Bong Joon-ho |

| Asian Film Award - Special Mention | Jealousy Is My Middle Name | Park Chan-ok | |

| 2004 | Best Director | The President's Barber | Im Chan-sang |

| Audience Award | |||

| Asian Film Award | Possible Changes | Min Byeong-guk | |

| Asian Film Award - Special Mention | Springtime | Ryu Jang-ha | |

| 2009 | Asian Film Award | A Brand New Life | Ounie Lecomte |

| 2012 | Special Jury Prize | Juvenile Offender | Kang Yi-Kwan |

| Best Actor | Seo Young-Joo | ||

| 2013 | Audience Award | Red Family | Lee Ju-hyoung |

| Year | Award | Film | Recipient[70] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1989 | Golden Leopard | Why Has Bodhi-Dharma Left for the East? | Bae Yong-kyun |

| 2013 | Best Direction Award | Our Sunhi | Hong Sang-soo |

| 2015 | Golden Leopard | Right Now, Wrong Then |

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Table 8: Cinema Infrastructure - Capacity". UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- ^ "Table 6: Share of Top 3 distributors (Excel)". UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- ^ "Table 1: Feature Film Production - Method of Shooting". UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- ^ a b "Table 11: Exhibition - Admissions & Gross Box Office (GBO)". UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- ^ a b c Stamatovich, Clinton (25 October 2014). "A Brief History of Korean Cinema, Part One: South Korea by Era". Haps Magazine. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

- ^ a b Paquet, Darcy (2012). New Korean Cinema: Breaking the Waves. Columbia University Press. pp. 1–5. ISBN 978-0231850124..

- ^ a b Min, p.46.

- ^ a b Chee, Alexander (16 October 2017). "Park Chan-wook, the Man Who Put Korean Cinema on the Map". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ^ a b Nayman, Adam (27 June 2017). "Bong Joon-ho Could Be the New Steven Spielberg". The Ringer. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ^ Jin, Min-ji (13 February 2018). "Third 'Detective K' movie tops the local box office". Korea JoongAng Daily. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ^ 오, 승훈; 김, 경애 (2 November 2021). "한국 최초의 영화관 '애관극장' 사라지면 안되잖아요" ["We Can't Let the First Movie Theater in Korea, 'Ae Kwan Theater' Disappear"]. The Hankyoreh (in Korean). Retrieved 10 September 2023.

- ^ 이, 재덕 (7 February 2015). 저당 잡힌 '109살 한국 예술의 요람' 단성사는 웁니다 [Dansungsa, the '109 Year Old Cradle of Korean Cinema', Weeps After Being Mortgaged]. Kyunghyang Shinmun. Retrieved 10 September 2023.

- ^ "Viva Freedom! (Jayumanse) (1946)". Korean Film Archive. Archived from the original on 14 March 2018. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ^ Gwon, Yeong-taek (10 August 2013). 한국전쟁 중 제작된 영화의 실체를 마주하다 [Facing the reality of film produced during the Korean War]. Korean Film Archive (in Korean). Archived from the original on 8 September 2014. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ^ a b Paquet, Darcy (1 March 2007). "A Short History of Korean Film". KoreanFilm.org. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ^ Paquet, Darcy. "1945 to 1959". KoreanFilm.org. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- ^ McHugh, Kathleen; Abelmann, Nancy, eds. (2005). South Korean Golden Age Melodrama: Gender, Genre, and National Cinema. Wayne State University Press. pp. 25–38. ISBN 0814332536.

- ^ Goldstein, Rich (30 December 2014). "Propaganda, Protest, and Poisonous Vipers: The Cinema War in Korea". The Daily Beast. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

- ^ a b c d Paquet, Darcy. "1960s". KoreanFilm.org. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ^ a b "Prizes & Honours 1961". Berlin International Film Festival. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ^ a b c Rousse-Marquet, Jennifer (10 July 2013). "The Unique Story of the South Korean Film Industry". French National Audiovisual Institute (INA). Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ^ a b Kim, Molly Hyo (2016). "Film Censorship Policy During Park Chung Hee's Military Regime (1960-1979) and Hostess Films" (PDF). IAFOR Journal of Cultural Studies. 1 (2): 33–46. doi:10.22492/ijcs.1.2.03 – via wp-content.

- ^ Gateward, Frances (2012). "Korean Cinema after Liberation: Production, Industry, and Regulatory Trend". Seoul Searching: Culture and Identity in Contemporary Korean Cinema. SUNY Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0791479339.

- ^ Kai Hong, "Korea (South)", International Film Guide 1981, p.214. quoted in Armes, Roy (1987). "East and Southeast Asia". Third World Film Making and the West. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. p. 156. ISBN 0-520-05690-6.

- ^ Taylor-Jones, Kate (2013). Rising Sun, Divided Land: Japanese and South Korean Filmmakers. Columbia University Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-0231165853.

- ^ a b Paquet, Darcy. "1970s". KoreanFilm.org. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ^ Min, p.51-52.

- ^ Hartzell, Adam (March 2005). "A Review of Im Kwon-Taek: The Making of a Korean National Cinema". KoreanFilm.org. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ^ a b Chua, Beng Huat; Iwabuchi, Koichi, eds. (2008). East Asian Pop Culture: Analysing the Korean Wave. Hong Kong University Press. pp. 16–22. ISBN 978-9622098923.

- ^ Paquet, Darcy. "The Korean Film Industry: 1992 To The Present" in New Korean Cinema. Edited by Chi-Yun Shin and Julia Stringer, 35. Edinburgh, U.K: Edinburgh University Press. 2005.

- ^ Park, Seung Hyun. 2002. "Film Censorship And Political Legitimation In South Korea, 1987-1992". Cinema Journal 42 (1): 123. doi:10.1353/cj.2002.0024.

- ^ Paquet, Darcy. 2009. New Korean Cinema: Breaking The Waves (Short Cuts). New York, USA: Columbia University Press.

- ^ Sohn, Hee Jeong. 2020. "Feminism Reboot: Korean Cinema Under Neoliberalism In The 21St Century". Journal Of Japanese And Korean Cinema 12 (2): 100. doi:10.1080/17564905.2020.1840031.

- ^ Jameson, Sam (19 June 1989). "U.S. Films Troubled by New Sabotage in South Korea Theater". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "'Movie Industry Heading for Crisis'". The Korea Times.

- ^ Brown, James (9 February 2007). "Screen quotas raise tricky issues". Variety.

- ^ "Korean movie workers stage mass rally to protest quota cut". Korea Is One. Archived from the original on 26 May 2006. Retrieved 11 February 2010.

- ^ Artz, Lee; Kamalipour, Yahya R., eds. (2007). The Media Globe: Trends in International Mass Media. New York: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers. p. 41. ISBN 978-0742540934.

- ^ Rosenberg, Scott (1 December 2004). "Thinking Outside the Box". Film Journal International. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- ^ Lee, Hyo-won (18 November 2013). "Original 'Oldboy' Gets Remastered, Rescreened for 10th Anniversary in South Korea". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ a b "Box Office: All Time". Korean Film Council. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ Pomerantz, Dorothy (8 September 2014). "What The Economics Of 'Snowpiercer' Say About The Future Of Film". Forbes. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ Kang Kim, Hye Won (11 January 2018). "Could K-Film Ever Be As Popular As K-Pop In Asia?". Forbes. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ "PARASITE Crowned Best Foreign Language Film at Golden Globes". Korean Film Biz Zone.

- ^ Khatchatourian, Klaritza Rico,Maane; Rico, Klaritza; Khatchatourian, Maane (10 February 2020). "'Parasite' Becomes First South Korean Movie to Win Best International Film Oscar".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Leanne Dawson (2015) Queer European Cinema: queering cinematic time and space, Studies in European Cinema, 12:3, 185-204, doi:10.1080/17411548.2015.1115696.

- ^ a b c d Kim, Ungsan (2 January 2017). "Queer Korean cinema, national others, and making of queer space in Stateless Things (2011)". Journal of Japanese and Korean Cinema. 9 (1): 61–79. doi:10.1080/17564905.2017.1296803. ISSN 1756-4905. S2CID 152116199.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i 김필호; C. COLIN SINGER (June 2011). "Three Periods of Korean Queer Cinema: Invisible, Camouflage, and Blockbuster". Acta Koreana. 14 (1): 117–136. doi:10.18399/acta.2011.14.1.005. ISSN 1520-7412.

- ^ a b c d Lee, Jooran (28 November 2000). "Remembered Branches: Towards a Future of Korean Homosexual Film". Journal of Homosexuality. 39 (3–4): 273–281. doi:10.1300/J082v39n03_12. ISSN 0091-8369. PMID 11133136. S2CID 26513122.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Shin, Jeeyoung (2013). "Male Homosexuality in The King and the Clown: Hybrid Construction and Contested Meanings". Journal of Korean Studies. 18 (1): 89–114. doi:10.1353/jks.2013.0006. ISSN 2158-1665. S2CID 143374035.

- ^ Giammarco, Tom. (2013). Queer Cinema. In C. Balmain (Ed.), Directory of World Cinema: South Korea (pp. 170-171) Chicago, IL: Intellect.

- ^ Balmain, Colette. (2013). Queer Cinema. In C. Balmain (Ed.), Directory of World Cinema: South Korea (pp. 175-176) Chicago, IL: Intellect.

- ^ Kim, Ungsan (2 January 2017). "Queer Korean cinema, national others, and making of queer space in Stateless Things (2011)". Journal of Japanese and Korean Cinema. 9 (1): 61–79. doi:10.1080/17564905.2017.1296803. ISSN 1756-4905. S2CID 152116199.

- ^ a b Conran, Pierce. (2013). Queer Cinema. In C. Balmain (Ed.), Directory of World Cinema: South Korea (pp. 178-179) Chicago, IL: Intellect.

- ^ a b Giammarco, Tom. (2013). Queer Cinema. In C. Balmain (Ed.), Directory of World Cinema: South Korea (pp. 173-174) Chicago, IL: Intellect.

- ^ 영화 '아가씨' 원작… 800쪽이 금세 읽힌다. The Chosun Ilbo (in Korean). 20 July 2020. Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- ^ a b c Shin, Chi-Yun (2 January 2019). "In another time and place: The Handmaiden as an adaptation". Journal of Japanese and Korean Cinema. 11 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1080/17564905.2018.1520781. ISSN 1756-4905.

- ^ a b Peirse, Alison; Martin, Daniel (14 March 2013). Korean Horror Cinema. p. 1. doi:10.1515/9780748677658. ISBN 978-0-7486-7765-8.

- ^ The Playlist Staff (26 June 2014). "Primer: 10 Essential Films Of The Korean New Wave". IndieWire. Retrieved 18 November 2023.

- ^ Paquet, Darcy. "Film Awards Ceremonies in Korea". KoreanFilm.org. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ Steger, Isabella (10 October 2017). "South Korea's Busan film festival is emerging from under a dark political cloud". Quartz. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ "IMDb OSCARS". IMDb. Retrieved 21 March 2021.

- ^ "Prizes & Honours". Berlin International Film Festival. Archived from the original on 21 March 2019. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ "Cannes Film Festival". IMDb. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ "History of Biennale Cinema". La Biennale di Venezia. 7 December 2017. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ "Announcing the TIFF '19 Award Winners". TIFF. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- ^ "2013 Sundance Film Festival Announces Feature Film Awards". Sundance Institute. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- ^ "Telluride Film Festival". IMDb. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- ^ "Tokyo International Film Festival". IMDb. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ "Locarno International Film Festival". IMDb. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- Bowyer, Justin (2004). The Cinema of Japan and Korea. London: Wallflower Press. ISBN 1-904764-11-8.

- Min, Eungjun; Joo Jinsook; Kwak HanJu (2003). Korean Film : History, Resistance, and Democratic Imagination. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 0-275-95811-6.

- New Korean Cinema (2005), ed. by Chi-Yun Shin and Julian Stringer. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0814740309