Souders–Brown equation

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2020) |

In chemical engineering, the Souders–Brown equation (named after Mott Souders and George Granger Brown[1][2]) has been a tool for obtaining the maximum allowable vapor velocity in vapor–liquid separation vessels (variously called flash drums, knockout drums, knockout pots, compressor suction drums and compressor inlet drums). It has also been used for the same purpose in designing trayed fractionating columns, trayed absorption columns and other vapor–liquid-contacting columns.

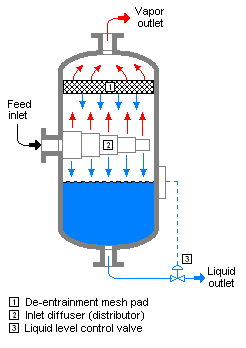

A vapor–liquid separator drum is a vertical vessel into which a liquid and vapor mixture (or a flashing liquid) is fed and wherein the liquid is separated by gravity, falls to the bottom of the vessel, and is withdrawn. The vapor travels upward at a design velocity which minimizes the entrainment of any liquid droplets in the vapor as it exits the top of the vessel.

Use

[edit]The diameter of a vapor–liquid separator drum is dictated by the expected volumetric flow rate of vapor and liquid from the drum. The following sizing methodology is based on the assumption that those flow rates are known.

Use a vertical pressure vessel with a length–diameter ratio of about 3 to 4, and size the vessel to provide about 5 minutes of liquid inventory between the normal liquid level and the bottom of the vessel (with the normal liquid level being somewhat below the feed inlet).

Calculate the maximum allowable vapor velocity in the vessel by using the Souders–Brown equation:

where

- v is the maximum allowable vapor velocity in m/s

- ρL is the liquid density in kg/m3

- ρV is the vapor density in kg/m3

- k = 0.107 m/s (when the drum includes a de-entraining mesh pad)

Then the cross-sectional area of the drum can be found from:

where

- is the vapor volumetric flow rate in m3/s

- A is the cross-sectional area of the drum

And the drum diameter is:

The drum should have a vapor outlet at the top, liquid outlet at the bottom, and feed inlet at about the half-full level. At the vapor outlet, provide a de-entraining mesh pad within the drum such that the vapor must pass through that mesh before it can leave the drum. Depending upon how much liquid flow is expected, the liquid outlet line should probably have a liquid level control valve.

As for the mechanical design of the drum (materials of construction, wall thickness, corrosion allowance, etc.) use the same criteria as for any pressure vessel.

Recommended values of k

[edit]The GPSA Engineering Data Book[3] recommends the following k values for vertical drums with horizontal mesh pads (at the denoted operating pressures):

- At a gauge pressure of 0 bar: 0.107 m/s

- At a gauge pressure of 7 bar: 0.107 m/s

- At a gauge pressure of 21 bar: 0.101 m/s

- At a gauge pressure of 42 bar: 0.092 m/s

- At a gauge pressure of 63 bar: 0.083 m/s

- At a gauge pressure of 105 bar: 0.065 m/s

GPSA notes:

- k = 0.107 at a gauge pressure of 7 bar. Subtract 0.003 for every 7 bar above a gauge pressure of 7 bar.

- For glycol or amine solutions, multiply above k values by 0.6 – 0.8

- Typically use one-half of the above k values for approximate sizing of vertical separators without mesh pads

- For compressor suction scrubbers and expander inlet separators, multiply k by 0.7 – 0.8

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ M. Souders and G. G. Brown (1934). "Design of Fractionating Columns, Entrainment and Capacity". Industrial & Engineering Chemistry. 38 (1): 98–103. doi:10.1021/ie50289a025.

- ^ Analytical Study of Liquid/Vapour Separation Efficiency Archived 2009-04-24 at the Wayback Machine, study developed by W.D. Monnery, Chem-Pet Process Technology Ltd. and W.Y. Svrcek, University of Calgary, Calgary, Canada, 2005, for Petroleum Technology Alliance Canada

- ^ Gas Processing Suppliers Association (GPSA) (1987). Engineering Data Book. Vol. 1 (10th ed.). Gas Processing Suppliers Association, Tulsa, Oklahoma.