Sonnet 19

| Sonnet 19 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

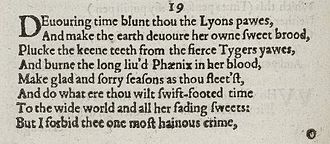

The first two stanzas of Sonnet 19 in the 1609 Quarto | |||||||

| |||||||

Sonnet 19 is one of 154 sonnets published by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare in 1609. It is considered by some to be the final sonnet of the initial procreation sequence. The sonnet addresses time directly, as it allows time its great power to destroy all things in nature, but the poem forbids time to erode the young man's fair appearance. The poem casts time in the role of a poet holding an “antique pen”. The theme is redemption, through poetry, of time's inevitable decay. Though there is compunction in the implication that the young man himself will not survive time's effects, because redemption brought by the granting of everlasting youth is not actual, but rather ideal or poetic.[2]

Structure

[edit]Sonnet 19 is a typical English or Shakespearean sonnet. The English sonnet consists of three quatrains followed by a couplet. It follows the form's typical rhyme scheme: ABAB CDCD EFEF GG. Like all but one of Shakespeare's sonnets, Sonnet 19 is written in a type of metre called iambic pentameter based on five pairs of metrically weak/strong syllabic positions. The eighth line exemplifies a regular iambic pentameter:

× / × / × / × / × / But I forbid thee one most heinous crime: (19.8)

- / = ictus, a metrically strong syllabic position. × = nonictus.

Both the first and third lines exhibit reversals which thrust extra emphasis on an action verb, a practice Marina Tarlinskaja calls rhythmical italics[3]

(line three also exhibits an ictus moved to the right, resulting in a four-position figure, × × / /, sometimes referred to as a minor ionic):

× / × / / × × /× / Devouring Time, blunt thou the lion's paws, (19.1) / × × / × × / / × / Pluck the keen teeth from the fierce tiger's jaws, (19.3)

Synopsis and analysis

[edit]Sonnet 19 addresses time directly as "Devouring Time", a translation of the often-used phrase from Ovid, "tempus edax" (Met. 15.258).[4] G. Wilson Knight notes and analyzes the way in which devouring time is developed by trope in the first 19 sonnets.[citation needed] Jonathan Hart notes the reliance of Shakespeare's treatment on tropes from not only Ovid but also Edmund Spenser.[citation needed]

The sonnet consists of a series of imperatives, where time is allowed its great power to destroy all things in nature: As it will "blunt ... the lion's paws;" cause mother earth to "devour" her children ("own sweet brood"); and ("pluck") the tiger's "keen teeth", its 'eager', its 'sharp', and its 'fierce' teeth from the jaw of a tiger. The quarto's "yawes" was amended to "jaws" by Edward Capell and Edmond Malone; this change is now almost universally accepted.[citation needed]

Time will even "burn the long-liv'd phoenix, in her blood." The phoenix is a long-lived bird that is cyclically regenerated or reborn. Associated with the sun, a phoenix obtains new life by arising from the ashes of its predecessor. George Steevens glosses "in her blood" as "burned alive" by analogy with Coriolanus (4.6.85); Nicolaus Delius has the phrase "while still standing."[citation needed]

As time speeds by ("fleet'st", although variations in early modern spelling allow "flee'st" as in 'time flies' or 'tempus fugit'), it will bring the seasons ("make glad and sorry seasons"), which are not only cycles of nature but ups and downs of human moods. Time may "do what ere thou wilt." The epithet "swift-footed time" was commonplace, as was "the wide world".[4]

Finally the poet forbids time a most grievous sin ("one most hainous crime"): It must "carve not with thy hours my love's fair brow". In associating crime and wrinkles Shakespeare has drawn on Ovid again, "de rugis crimina multa cadunt" ('from wrinkles many crimes are exposed' from Amores 1.8.46), rendered by Christopher Marlowe as "wrinckles in beauty is a grieuous fault".[4] The hours must not etch into the beloved's brow any wrinkle (compare Sonnet 63, "When hours have .. fill'd his brow / With lines and wrinkles"). Nor must time's "antique pen," both its 'ancient' and its 'antic' or crazy pen, "draw ... lines there".[4]

Time must allow the youth to remain "untainted" in its "course"; one meaning of "untainted" (from tangere = to touch) is 'untouched' or 'unaffected' by the course of time. The couplet asserts that time may do its worst ("Yet do thy worst old Time") – whatever injuries or faults ("wrongs") time might commit, the poet's "love," both his affection and the beloved, will live forever young in the poet's lines ("verse").

Interpretations

[edit]In Gustav Holst's opera, At the Boar's Head, the sonnet is performed as a song sung by Prince Hal in disguise as entertainment for Falstaff and Doll Tearsheet.

David Harewood reads it for the 2002 compilation album, When Love Speaks (EMI Classics)

References

[edit]- ^ Pooler, C[harles] Knox, ed. (1918). The Works of Shakespeare: Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare [1st series]. London: Methuen & Company. OCLC 4770201.

- ^ Shakespeare, William. Duncan-Jones, Katherine. Shakespeare’s Sonnets. Bloomsbury Arden 2010. ISBN 9781408017975. p. 148

- ^ Tarlinskaja, Marina (2014). Shakespeare and the Versification of English Drama, 1561–1642. Farnham: Ashgate. pp. 29–32. ISBN 978-1-4724-3028-1.

- ^ a b c d Larsen, Kenneth J. "Sonnet 19". Essays on Shakespeare's Sonnets. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

Further reading

[edit]- Baldwin, T. W. (1950). On the Literary Genetics of Shakspeare's Sonnets. University of Illinois Press, Urbana.

- Hart, Jonathan (2002). "Conflicting Monuments." In the Company of Shakespeare. AUP, New York.

- Hubler, Edwin (1952). The Sense of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

- Schoenfeldt, Michael (2007). The Sonnets: The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare's Poetry. Patrick Cheney, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- First edition and facsimile

- Shakespeare, William (1609). Shake-speares Sonnets: Never Before Imprinted. London: Thomas Thorpe.

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1905). Shakespeares Sonnets: Being a reproduction in facsimile of the first edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 458829162.

- Variorum editions

- Alden, Raymond Macdonald, ed. (1916). The Sonnets of Shakespeare. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. OCLC 234756.

- Rollins, Hyder Edward, ed. (1944). A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare: The Sonnets [2 Volumes]. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. OCLC 6028485. — Volume I and Volume II at the Internet Archive

- Modern critical editions

- Atkins, Carl D., ed. (2007). Shakespeare's Sonnets: With Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-4163-7. OCLC 86090499.

- Booth, Stephen, ed. (2000) [1st ed. 1977]. Shakespeare's Sonnets (Rev. ed.). New Haven: Yale Nota Bene. ISBN 0-300-01959-9. OCLC 2968040.

- Burrow, Colin, ed. (2002). The Complete Sonnets and Poems. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192819338. OCLC 48532938.

- Duncan-Jones, Katherine, ed. (2010) [1st ed. 1997]. Shakespeare's Sonnets. Arden Shakespeare, third series (Rev. ed.). London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4080-1797-5. OCLC 755065951. — 1st edition at the Internet Archive

- Evans, G. Blakemore, ed. (1996). The Sonnets. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521294034. OCLC 32272082.

- Kerrigan, John, ed. (1995) [1st ed. 1986]. The Sonnets ; and, A Lover's Complaint. New Penguin Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-070732-8. OCLC 15018446.

- Mowat, Barbara A.; Werstine, Paul, eds. (2006). Shakespeare's Sonnets & Poems. Folger Shakespeare Library. New York: Washington Square Press. ISBN 978-0743273282. OCLC 64594469.

- Orgel, Stephen, ed. (2001). The Sonnets. The Pelican Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140714531. OCLC 46683809.

- Vendler, Helen, ed. (1997). The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-63712-7. OCLC 36806589.

External links

[edit] Works related to Sonnet_19_(Shakespeare) at Wikisource

Works related to Sonnet_19_(Shakespeare) at Wikisource- Paraphrase and analysis (Shakespeare-online)

- Analysis