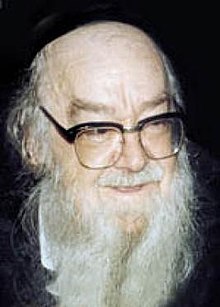

Sholom Schwadron

Rabbi Sholom Schwadron | |

|---|---|

| |

| Title | Maggid of Jerusalem |

| Personal life | |

| Born | Sholom Mordechai Schwadron 1912 |

| Died | 21 December 1997 Jerusalem |

| Nationality | Israeli |

| Spouse | Leah Auerbach |

| Parent(s) | Rabbi Yitzchak and Freida Schwadron |

| Alma mater | Hebron yeshiva |

| Religious life | |

| Religion | Judaism |

| Denomination | Haredi |

| Other | Mashgiach ruchani, Yeshivat Tiferet Tzvi Rosh yeshiva, Mekor Chaim Yeshiva |

| Buried | Mount of Olives |

Sholom Mordechai Hakohen Schwadron (Hebrew: הרב שלום מרדכי הכהן שבדרון) (1912–21 December 1997) was a Haredi rabbi and orator. He was known as the "Maggid of Jerusalem" for his fiery, inspirational mussar talks. Some of the stories he told about the character and conduct of Torah leaders and tzadikim of previous generations were incorporated in the "Maggid" series of books by Rabbi Paysach Krohn, whom Rabbi Schwadron mentored.

Early life

[edit]Rabbi Schwadron was born in the Beit Yisrael neighborhood of Jerusalem to Rabbi Yitzchak and Freida Schwadron. His father was formerly the av beis din (head of the rabbinical court) of Khotymyr. He was the son of Rabbi Sholom Mordechai Schwadron, a leading halachic authority known by the Hebrew acronym Maharsham.[1][2]

This was his father's second marriage. Rabbi Yitzchak Schwadron was widowed of his first wife, Chaya Leah, in 1898, leaving him with nine children.[3] In 1903 he immigrated to Palestine with four of his children and remarried Freida, who raised the orphans as her own.[4] Yitzchak and Freida Schwadron had six more children together.[4] Their son Sholom, born a year and a half after the death of the Maharsham, was named after his illustrious grandfather.[5]

Rabbi Yitzchak Schwadron died at the age of 63, leaving Freida a widow at the age of 35 and young Sholom an orphan at the age of 7.[6] Freida struggled to support her young children, as well as her sickly brother who lived with her, by selling bread door to door. At night she found time to recite Psalms, and share with her children their father's Torah legacy.[6] Schwadron later published some of his father's Torah thoughts in the introductions to his books, Oholei Shem and Daas Torah Maharsham (Part II).[7]

For a few years, Sholom was forced to live at the Diskin Orphanage in Jerusalem.[8] At the age of 12 he entered Yeshivat Tzion under Rabbi Yaakov Katzenelenbogen. At the age of 15 he entered the Lomza Yeshiva in Petach Tikva under Rabbi Eliyahu Dushnitzer.[9]

Despite his family privation, Rabbi Schwadron developed into a Torah scholar of note. By the age of 18 he was learning 700 pages of Gemara every semester at the Hebron yeshiva,[8] which had relocated to Jerusalem after the 1929 Hebron massacre.[10] In the seven years that he studied at Hebron yeshiva, he became the talmid muvhak (close student) of the mashgiach ruchani, Rabbi Leib Chasman.[11][12] He also studied under Rabbi Elya Lopian, Rabbi Yechezkel Levenstein,[8] and Rabbi Meir Chodosh.[13]

Marriage

[edit]On the Friday of Hanukkah 1936,[14] Rabbi Schwadron married Leah Auerbach, daughter of Rabbi Chaim Yehuda Leib Auerbach, rosh yeshiva of Shaar Hashamayim Yeshiva. Rabbi Auerbach was a well-known Jerusalem personality whose extreme poverty was only matched by his love of Torah and Torah scholars.[15]

A story from the early days of Rabbi Schwadron's marriage illustrates the dire poverty found in the Auerbach household. As part of the dowry agreement, Rabbi Auerbach and his wife committed to supporting their son-in-law for the first three years of his marriage. On the first day, he came to eat breakfast and was served black bread, cream, a cup of coffee and halva by his mother-in-law. Rabbi Schwadron ate the meal, thanked his mother-in-law, and went to learn. The next morning, he realized that his wife hadn't joined him and asked where she was. "Oh, she had to go somewhere," Rebbetzin Auerbach replied. On the third morning, when his wife still didn't join him, Rabbi Schwadron became worried and demanded to know what was going on. His mother-in-law tearfully admitted that they had agreed to support him, but had no money to support her too. Rabbi Schwadron's wife would come in after he left and make do with bread and water for breakfast.[16]

Rabbi Schwadron founded his own home on simplicity and lack of luxury. He and his family lived in a small, two-room apartment in the Sha'arei Hesed neighborhood of Jerusalem, which lacked a refrigerator, a bathtub, a washing machine or running water. Water was drawn from a nearby well. The kitchen, located in the courtyard, was so small that it did not fulfill the halachic requirement for a mezuzah.[17] Yet despite the lack of space and conveniences, the family was known for sharing everything it had with drop-in visitors and indigent guests.[18]

Rabbi Schwadron was the first son-in-law of Rabbi Auerbach.[13] He was the brother-in-law of Rabbi Shlomo Zalman Auerbach, rosh yeshiva of Yeshivat Kol Torah in Bayit Vegan, with whom he enjoyed a long and productive relationship as learning partners and friends, and Rabbi Simcha Bunim Leizerson, founding president of the Chinuch Atzmai school system.[8]

Following his marriage, Rabbi Schwadron joined the Ohel Torah kollel, where he learned alongside future Torah leaders such as Rabbi Shmuel Wosner, Rabbi Eliezer Waldenberg, and Rabbi Yosef Shalom Elyashiv. He also taught an evening Gemara class to residents of Shaarei Chesed, the neighborhood in which he now lived, and learned each night with his brother-in-law, Rabbi Shlomo Zalman Auerbach. In 1937, he was asked to deliver a more advanced evening Gemara shiur in Shaarei Chesed, a class he taught for the next 25 years.[19]

In 1943, he became mashgiach ruchani at Yeshivat Tiferet Tzvi for young teens. The talks he gave to the students, as well as his personal example of total concentration in his own learning, made a lasting impression on these boys.[20] Rabbi Schwadron exerted a similar positive influence on Sephardi students at Mekor Chaim Yeshiva, where he served as rosh yeshiva from 1950 to 1960. He taught the highest shiur, establishing personal relationships with students that often lasted three or four decades.[21]

At the urging of the Brisker Rav, Rabbi Schwadron became a spokesman for the Peylim organization, which promoted the spiritual rescue of Jewish children who had emigrated from Yemen and Morocco and were being housed in absorption camps.[22]

Maggid of Jerusalem

[edit]In 1952, Rabbi Schwadron began giving a Friday-night lecture to the public at the Zikhron Moshe shtiebel near the Geula neighborhood of Jerusalem. It was this lecture, which continued for the next 40 years, that earned Schwadron the title of "Maggid of Jerusalem."[23]

He opened each talk with halacha and ended with fiery mussar, penetrating his listeners' hearts and inspiring them to self-improvement.[23] A master at storytelling, Rabbi Schwadron was able to draw out his audience's emotions using sing-song, witty remarks, and exaggerated mannerisms before delivering the "punch line" of his call to change. Often he punctuated the irony of human foibles with a booming laugh and the words, "Pilei ployim, hafla vafelle! (Wonder of wonders! Amazing!)"[8]

Following is the description of one speech delivered in the Hebrew month of Elul, as Rabbi Schwadron prepared his listeners to undertake serious contemplation and teshuvah before Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur:

"Imagine that the inhabitants of the local cemetery were given the opportunity by the Heavenly Court to return to this world for just one hour. Just one hour, just one hour," he sang in a mournful tone of voice.

"Look at the door!" he startled the audience. "There is the elte bubbe (great- grandmother) and the old rabbi who passed away last year! And there is Berel and Yankel and Yossel! They're all coming in!"

The listeners spun around, actually expecting to see the long departed members of their community walk through the ornate doorway. The vivid descriptions portrayed by the orator transported the crowded shul members into a dizzying whirl as they pictured the town filled up by the departed.

"Move over," continued the speaker relentlessly. "'Make place for me,' the former departed are screaming. 'We have just one hour!' Just one hour, just one hour," he intoned in that special tone unique to maggids.

The mournful tones and mannerisms employed by the maggid played on the listeners' emotions, putting his audience exactly where he wanted it to be: with thoughts of God's greatness, man's mortality, and the teshuvah period.[8]

In the course of his talks, Rabbi Schwadron publicized many stories about leading rabbis and tzadikim of previous generations.[8] Some of these stories were included in Rabbi Paysach Krohn's books, The Maggid Speaks (on which Schwadron collaborated) and Echoes of the Maggid (published after Rabbi Schwadron's death).

Just as he exhorted others to change and improve, Rabbi Schwadron constantly worked on improving himself. From the time of his marriage until into his eighties, he made a ta’anit dibbur (תענית דבור, abstention from speaking) every Monday and Thursday, as well as during the 40-day period from the first day of the month of Elul until Yom Kippur.[8][24]

Relationship with the Krohns

[edit]Rabbi Schwadron traveled abroad frequently to raise money for the institutions with which he was involved. During his months-long stays, he would address congregations, conventions, and other assemblies, solidifying his title of "Maggid".[8]

It was on one of these trips, in late 1964, that he was invited by Rabbi Avrohom Zelig Krohn, father of Rabbi Paysach Krohn, to stay at his home in New York, even though Rabbi Schwadron didn't know him or his family personally. Rabbi Schwadron insisted on paying rent, which Rabbi Krohn agreed to reluctantly. During the five months that Rabbi Schwadron resided with the Krohns, a close bond formed between him and the family. When Rabbi Schwadron announced that he was leaving after Passover 1965 to travel back to Israel by boat, the entire family saw him off at the pier. Then Rabbi Krohn handed Rabbi Schwadron an envelope containing all the "rent money" he had paid, as he had never intended to keep it.[25]

A few days later, Rabbi Krohn said he missed his guest so much that he decided to greet him when his boat docked in Israel. He and his wife quickly arranged passports and flew to Israel two days before Schwadron arrived. After giving the Rabbi Schwadron family their own time for a reunion, the Krohns appeared with their own welcome.[26]

Rabbi Krohn was diagnosed with a terminal illness after this event, and died a year later. Six months after that, the family received a letter from Rabbi Schwadron saying that he was coming to America again. Rabbi Schwadron became a surrogate father to Krohn's seven orphans.[27] He showed great sensitivity towards Rabbi Krohn's widow, remembering his own mother's struggles to raise her orphaned children.[8]

With Rabbi Schwadron's encouragement and active input, Rabbi Paysach Krohn penned the first of his popular "Maggid" books, The Maggid Speaks, published in 1987.[28] Subsequent titles (Along the Maggid's Journey, In the Footsteps of the Maggid) memorialized Schwadron's influence on the overall project. After Schwadron died, Krohn's titles reflected that fact, too (Echoes of the Maggid, Reflections of the Maggid).

Personal vignettes

[edit]R. Shalom was known for his personal piety. During the entire month of Elul, R. Shalom would undertake a Taanis Dibur, refraining from talking except for Divray Torah and mussar.

Published works

[edit]Rabbi Schwadron wrote, annotated and edited more than 25 sefarim, mainly those penned by his grandfather, the Maharsham.[12] These include:

- She'eilot U'teshuvot Maharsham

- Oholei Shem

- Daas Torah Maharsham

He also edited and published two famous mussar texts composed by his teachers — Ohr Yahel by Rabbi Leib Chasman and Lev Eliyahu by Rabbi Elyah Lopian.[12][29]

Later years

[edit]Schwadron's mother, Freida, died in 1962. His wife, Leah, died in 1977.[12]

Rabbi Schwadron died on December 21, 1997 (22 Kislev 5758).[8] He was buried in the Jewish cemetery on the Mount of Olives.[30]

References

[edit]- ^ Lazewnik (2000), pp. 90–91.

- ^ Tzinovitz, Moshe. "Rabbi Shalom Mordechai HaCohen Schwadron". buchach.org. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

- ^ Lazewnik (2000), p. 379.

- ^ a b Lazewnik (2000), p. 91.

- ^ Lazewnik (2000), p. 380.

- ^ a b Lazewnik (2000), pp. 92–93.

- ^ Lazewnik (2000), pp. 380–381.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Donn, Yochonon. "The Maggid of Jerusalem: 10 Years Since His Passing". Hamodia, 13 December 2007, pp. C6-C7.

- ^ Lazewnik (2000), p. 381.

- ^ Lazewnik (2000), p. 383.

- ^ Lazewnik (2000), p. 384.

- ^ a b c d Krohn (1987), p. 20.

- ^ a b Lazewnik (2000), p. 387.

- ^ Lazewnik (2000), pp. 29, 387.

- ^ Lazewnik (2000), p. 36.

- ^ Lazewnik (2000), pp. 32–33.

- ^ Lazewnik (2000), pp. 30–31.

- ^ Lazewnik (2000), pp. 63–66.

- ^ Lazewnik (2000), pp. 388–389.

- ^ Lazewnik (2000), p. 390.

- ^ Lazewnik (2000), p. 391.

- ^ Lazewnik (2000), p. 394.

- ^ a b Lazewnik (2000), p. 395.

- ^ Lazewnik (2000), p. 388.

- ^ Krohn (1987), pp. 26–29.

- ^ Krohn (1987), pp. 29–30.

- ^ Krohn (1987), pp. 30–31.

- ^ Krohn (1987), p. 14.

- ^ Lazewnik (2000), pp. 225–226.

- ^ "Notables Interred on Har HaZeitim". Har Hazeisim Preservation. 2011. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

Sources

[edit]- Krohn, Rabbi Paysach J. (1987). The Maggid Speaks: Favorite stories and parables of Rabbi Sholom Schwardron shlita, Maggid of Jerusalem. Mesorah Publications, Ltd. ISBN 0-89906-230-X.

- Lazewnik, Libby (2000). Voice of Truth: The life and eloquence of Rabbi Sholom Schwadron, the unforgettable Maggid of Jerusalem. Brooklyn, N.Y.: Mesorah Publications, Ltd. ISBN 9781578195008.