Yan'an Soviet

| Shaan-Gan-Ning Border Region 陝甘寧邊區 | |

|---|---|

| Rump state of the Chinese Soviet Republic | |

| 1937–1950 | |

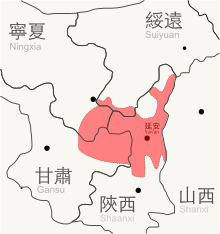

Map of Shaan-Gan-Ning Border Region. | |

| Capital | Yan'an (1937–47, 1948–49) Xi'an (1949–50) |

| Area | |

• 1937 | 134,500 km2 (51,900 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 1937 | 1,500,000 |

| Government | |

| Chairman | |

• 1937–1948 | Lin Boqu |

| Deputy Chairman | |

• 1937–1938 | Zhang Guotao |

• 1938–1945 | Gao Zili |

| Historical era | Chinese Civil War |

• 6 September | 1937 |

• Disestablished | 19 January 1950 |

| Today part of | China |

The Yan'an Soviet was a soviet governed by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) during the 1930s and 1940s. In October 1936 it became the final destination of the Long March, and served as the CCP's main base until after the Second Sino-Japanese War.[1]: 632 After the CCP and Kuomintang (KMT) formed the Second United Front in 1937, the Yan'an Soviet was officially reconstituted as the Shaan–Gan–Ning Border Region (traditional Chinese: 陝甘寧邊區; simplified Chinese: 陕甘宁边区; pinyin: Shǎn gān níng Biānqū; Wade–Giles: Shan3-kan1-ning2 Pien1-ch'ü1).[a][2] Yan'an is celebrated in CCP historical narratives as the most sacred of revolutionary sites and the birthplace of Mao Zedong Thought.[3]

Organization

[edit]The Shaan-Gan-Ning base area, of which Yan'an was a part, was founded in 1934.[4]: 129

During the Second Sino-Japanese War, the Shaan-Gan-Ning Border Region became one of a number of border region governments established by the Communists. Other regions included the Jin-Sui Border Region (in Shanxi and Suiyuan),[b] the Jin-Cha-Ji Border Region (in Shanxi, Chahar, and Hebei) and the Ji-Lu-Yu Border Region (in Hebei, Henan and Shandong).

Although not on the front lines of the Second Sino-Japanese War, the Shaan-Gan-Ning Border Region was the most politically important and influential revolutionary base area due to its function as the de facto capital of the Chinese Communist Revolution.[5]: 129

History

[edit]After the Long March, the CCP lost 90% of its members. General Mao Zedong was originally intent on heading to the USSR border, but changed his mind after hearing about a large soviet in Northern Shaanxi. Mao's army arrived in northern Shaanxi in 1935. When they arrived, they found a soviet wracked by sufan (purge) campaigns initiated by the local Politburo Central Committee under Liu Zhidan. The central leadership of the CCP ordered the purges stopped. Originally the KMT had control of practically all of the major cities, while the CCP only held a few counties in the countryside. Multiple attempts were made to move to richer lands, or to head to the USSR border to get support from the Soviets, but all were stymied.

The CCP took advantage of the increasing nationalism and the KMT's weak response to Japanese aggression to recruit allies. While Mao wanted a "united front against Chiang Kai-shek and Japanese aggression", the Comintern faction in the CCP, headed by Wang Ming, successfully pushed for an alliance with the KMT, against Mao's wishes. In December of 1936, the Xi'an Incident occurred, where Chiang was kidnapped by his own soldiers and forced to agree to a United Front with the CCP. The CCP took advantage of the chaos to expand the base in Shaanxi and take Yan'an. In January of 1937, the CCP headquarters were established in Yan'an. Early 1937 was a period of relative peace, where in many areas of Shaanxi the CCP shared administration with the KMT, however there were frequent disputes over taxation rights.[6]

On July 7th, 1937 the Marco Polo Bridge incident occurred, beginning the Second Sino-Japanese War. By this point Chiang Kai-shek was fully willing to negotiate with the CCP, and the Shaan-Gan-Ning Border Region was officially established. During this war, there was an internal power struggle between Mao and the pro-Soviet faction, headed by Wang Ming, who wanted closer relations with the KMT and a more aggressive strategy in the war of Resistance against Japan, following the Comintern line, while Mao wanted operational independence from the KMT and a more conservative strategy focused on guerilla warfare. Wang Jiaxiang, an ally of Mao, eventually successfully lobbied the USSR and got verbal recognition of Mao's leadership of the CCP. During the 6th Plenum of the 6th Central Committee (September 29–November 6, 1938), Mao used this verbal recognition to monopolize power of the CCP, and dealt a heavy blow to the power of Wang Ming.

By 1939, the KMT began to fear the CCP gaining strength and eventually attacked them in spring of that year. While the KMT took control of much of eastern Gansu, the CCP took control of the rich east including Suide. In the summer of 1940 Zhou Enlai met with Chiang's chief of staff and once again agreed on borders.

During this time Mao also began to seriously develop Mao Zedong Thought, and wrote many famous essays such as On Practice and On Contradiction. By the 1940s Mao had for all intents and purposes becomes the chief Marxist theoretician of the CCP. On May 19th of 1941, Mao also began the "Reform our Study Movement", to teach the Soviet Union's textbook History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union as well as Mao Zedong Thought. Mao also successfully used divide and conquer tactics to break his political opponents in the Comintern faction, and by 1941 the faction had basically dissolved.

On February 1st of 1942 Mao began the rectification campaign, to purge the party of the Comintern faction, May 4th ideology, and instate Mao Zedong Thought as the primary doctrine. Originally Mao encouraged criticism as a weapon against his enemies, but critics such as Wang Shiwei complained about egalitarianism and free discussion being replaced with censorship and self criticism, and the hierarchy of cadres. As a result, Mao held a struggle session against Wang Shiwei, who was eventually imprisoned and later executed in 1947. This was along with a general purge of the cultural community in 1942. Mao began pushing anti-intellectualism and prioritized making culture subservient to politics. Mao pushed constant self reflection and self criticism to shape Communist cadres into the "New Socialist Man". The Emergency Rescue Campaign, primarily carried out by Kang Sheng, commenced in April 1943. This brought the usage of mass rallies and struggle sessions, as well as self-criticism and confession, to a fever pitch. In many instances confessions were extracted through torture, and people frequently resorted to extreme exaggeration of crimes to prove repentance, as well as blaming others.[7] This campaign did not end until December 1943, when the USSR sent a cable denouncing the campaign.

In 1944 the reexamination campaign began and the Emergency Rescue Campaign was rolled back, with many of the confessions and verdicts reexamined. However by this point Mao had practically achieved his goals with the campaign. By May of 1944, the 7th Plenum of the 6th Central Committee was held, enshrining Mao Zedong Thought as the primary doctrine of the CCP and securing Mao supreme leadership over the CCP.

Throughout 1946, Mao aimed for peaceful reconciliation with the KMT, but Chiang refused and eventually negotiations broke down. In March of 1947, KMT forces attacked Yan'an directly and managed to capture it, but Mao led a guerilla campaign throughout the countryside and eventually managed to defeat the KMT and form the People's Republic of China.[8]

Society

[edit]By the early 1940s, Yan'an had 37,000-38,000 residents, with 7,000 of them being locals and the rest being CCP cadres. The Yan'an soviet was controlled by Central Committee planning, and heavily influenced by the experience of the Ruijin era. By 1937 many youth were migrating to Yan'an, and the CCP established a dozen schools. These schools played a key part in Yan'an political life, prioritizing ideological training. There was a rich intellectual cultural life and many publications, such as the New China Daily, Liberation Weekly, Political Affairs, and more. The schools and party organs were generally led by veteran cadres, who were often only in their late 20s and 30s. Yan'an was somewhat hierarchical, with veteran cadres getting much better treatments, rations, and social status.[8] Yan'an was culturally distinct from the rest of the Shaan-Gan-Ning border area, particularly Shaanbei, which was notoriously culturally conservative and traditional. The CCP installed elections throughout the Shaan-Gan-Ning border region. While they were one party systems, they still allowed a level of citizen input, and participation was high, particularly in the richer northeast.[6]

Because Yan'an was largely cut off from the rest of the world due to KMT blockades, it became a somewhat insular society. During 1942, Mao began reforming culture in Yan'an, cracking down on intellectualism, criticism, and liberalism, particularly after the Yan'an Forum on Literature and Art in 1942. In order to support the ongoing production campaign, the idea of a labor hero became more and more supported. By embracing and creating art about labor heroes, who were exemplars of production and the people's revolutionary cause, intellectuals could gain legitimacy in socialist society. Intellectuals were expected to go to the people and write from the perspective of the proletariat class. The most famous of these labor heroes was Wu Manyou.[9] The CCP also made use of traditional folk practices such as Northern Shaanxi storytelling to spread and disseminate Communist policies.[10]

While the CCP made strives to extend equal rights to women, they struggled against the traditional customs of arranged marriage and dowry. In 1939, the CCP reformed marriage law in order to allow free marriage and divorce, but this was frequently abused by the family of brides, who used the easy divorce to arrange marriages with a greater "caili" (a dowry given by the groom). Continued reforms were enacted in 1944 and 1946 to attempt to moderate these abuses and stop the sale of women via marriage.[11]

The CCP in Yan'an also developed a new form of legal practice known as "Ma Xiwu's Way". This practice emphasized the usage of both mediation and adjudication in local civil cases, through a process of soliciting community opinion, making court accessible and open to the whole community, and making decisions based on mass opinion and approval, under the guidance of a revolutionary judge. This was promoted as a democratic approach to the law, and principles of "Ma Xiwu's way" continue to be used even after the People's Republic of China was formed.[12]

Economy

[edit]Immediately after setting up the Soviet, the CCP began their "land revolution", confiscating property en-masse from the landlords and gentry of the region.[2]: 265 Its vigour in doing so resulted from two factors, its ideological commitment to peasant revolution and economic necessity. The base area's economic situation was precarious,[4]: 129 such that in 1936 the entire Soviet's revenue stood at just 1,904,649 yuan, of which some 652,858 yuan came from confiscation of property.[2]: 266 The program of land redistribution, the party's hostility towards merchants and its ban on opium depressed the local economy severely, and by 1936 the Communists were reduced to raiding nearby Shanxi (then ruled by Nationalist-backed warlord Yan Xishan) in order to acquire grain and other supplies.[2]: 266 The tightening of the Nationalist blockade in the same year made it difficult to secure resources from outside the region.[4]: 129 At no point during the period 1934-1941 was the Yan'an Soviet financially solvent, being dependent first on the confiscation of property from "enemy classes" and (after the formation of the Second United Front) on Nationalist aid,[2]: 265 the latter of which comprised around 70% of the Soviet's revenue from 1937 to 1940.[2]: 269

The region was already economically poor and sparsely populated, with low agricultural production and unreliable rainfall. Agriculture was mainly characterized by millet, beans, and sorghum, along with sheep and goats. There were no navigable rivers, and irrigation and commerce were minimal. The CCP government organized production campaigns in 1939 and 1940, and organized cadres into work units to assist with agriculture.[8] While early on most taxes besides the salt tax were eliminated, the tax burden began to grow, particularly in the 1940s as the party's state apparatus began to grow as well.[6] The CCP government also enacted the "cooperative movement" to decrease rents and interest rates for the peasants, as well as creating programs to share animals, tools, and seeds.[13]

The Nationalist blockade decreased during the Second United Front, but it was renewed when the alliance fell apart in 1941.[4]: 129 Japanese assaults in the region and poor harvests worsened the effects of blockade and the region had a severe economic crisis in 1941 and 1942.[4]: 130 By 1944, the region had suffered cumulative inflation of 564,700% since 1937, compared with 75,550% in Nationalist areas.[14] CCP leaders raised the issue of abandoning the area, which Mao Zedong refused to do.[4]: 130 Mao implemented a mass line strategy,[4]: 130 and imposed heavy taxes on the population in order to pay military expenses, which resulted in what is known as the "Yan'an Way", establishing the Border Region's independence from Nationalist subsidy.[14] However, the economy of the Border Region was also substantially supported by the production and export of opium into Japanese and Nationalist areas,[14] with academic Chen Yung-fa arguing that the economy of the Border Region was so dependent on opium that, had the CCP not engaged in opium trading, the Yan'an Way would have been impossible.[2]

Media

[edit]From July to October of 1936, journalist Edgar Snow visited the Yan'an commune, eventually writing the book Red Star Over China, which was extremely influential and shaped the perspective of many contemporary Chinese youth, who saw it as a mecca of revolutionary egalitarianism. As a result, many youth from KMT-held areas traveled to Yan'an.[6]

In January 1937, American journalist Agnes Smedley visited Yan'an.[15]: 165–166 In April, Helen Foster Snow traveled to Yan'an for research, interviewing Mao and other leaders.[15]: 166

The Eighth Route Army established its first film production group in the Yan'an Soviet during September 1938.[16]: 69

Well-known actor and director Yuan Muzhi arrived in Yan'an in the fall of 1938.[4]: 128 With Wu Yinxian, Yuan made a feature-length documentary, Yan'an and the Eighth Route Army, which depicted the Eighth Route Army's combat against the Japanese.[4]: 128 They also filmed Norman Bethune—a Canadian surgeon volunteering to help the Communists—performing surgeries close to the front lines.[4]: 128

In 1943, the CCP released their first campaign film, Nanniwan, which sought to develop relationships between the Red Army and local people in the Yan'an area by showcasing the army's production campaign to alleviate material shortages.[4]: 16

In 1944, the CCP welcomed a large group of foreign (primarily American) journalists to Yan'an.[15]: 17 In an effort to contrast the party with the Nationalists, the CCP generally did not censor these foreign reports.[15]: 17 In December 1945, the party's Central Committee instructed the party to facilitate the work of American journalists out of the hope that it would have a progressive influence on American policies toward China.[15]: 17–18

Diplomacy

[edit]After the US entry into World War II, the CCP sought military support from the US.[15]: 15 Mao welcomed the American Military Observation Group in Yan'an and in 1944 invited the US to establish a consulate there.[15]: 15

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Postal romanization: Shen–Kan–Ning. The name comes from the Chinese abbreviations of Shaanxi, Gansu, and Ningxia provinces.

- ^ Suiyuan is no longer a province, being incorporated into Inner Mongolia in 1954.

Citations

[edit]- ^ Van Slyke, Lyman (1986). "The Chinese Communist movement during the Sino-Japanese War 1937–1945". In Fairbank, John K.; Feuerwerker, Albert (eds.). Republican China 1912–1949, Part 2. The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 13. Cambridge University Press. pp. 609–722. doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521243384.013. ISBN 9781139054805.

- ^ a b c d e f g Chun, Yung-fa (1995). "The Blooming Poppy under the Red Sun: The Yan'an Way and the Opium Trade". In Saich, Tony; van de Ven, Hans (eds.). New Perspectives on the Chinese Revolution. New York: Routledge. ISBN 9781315702124.

- ^ Denton, Kirk (2012). "Yan'an as a Site of Memory in Socialist and Postsocialist China". In Matten, Marc André (ed.). Places of memory in modern China: history, politics, and identity. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-22096-6. Retrieved 11 December 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Qian, Ying (2024). Revolutionary Becomings: Documentary Media in Twentieth-Century China. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231204477.

- ^ Opper, Marc (2020). People's Wars in China, Malaya, and Vietnam. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. doi:10.3998/mpub.11413902. hdl:20.500.12657/23824. ISBN 978-0-472-90125-8. JSTOR 10.3998/mpub.11413902. S2CID 211359950.

- ^ a b c d Esherick, Joseph W. (2022). Accidental Holy Land: The Communist Revolution in Northwest China. University of California Press. doi:10.1525/luminos.117. ISBN 978-0-520-38532-0.

- ^ Jiang, Zhengyang (2020). "Between Instrumentalism and Moralism: Representation and Practice of the System of "Turning Oneself In" in the Shaan-Gan-Ning Border Region". Modern China. 46 (6): 585–611. doi:10.1177/0097700419873896. ISSN 0097-7004.

- ^ a b c Hua, Gao (2018). How the Red Sun Rose: The Origins and Development of the Yan’an Rectification Movement, 1930–1945. Translated by Mosher, Stacy; Jian, Guo. The Chinese University of Hong Kong Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctvbtzp48. ISBN 978-988-237-703-5.

- ^ Spakowski, Nicola (2021). "Moving Labor Heroes Center Stage: (Labor) Heroism and the Reconfiguration of Social Relations in the Yan'an Period". Journal of Chinese History. 5 (1): 83–106. doi:10.1017/jch.2020.4. ISSN 2059-1632.

- ^ Wu, Ka-ming (2015). "Traditional Revival with Socialist Characteristics: Propaganda Storytelling Turned into Spiritual Service". Reinventing Chinese tradition: the cultural politics of late socialism. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 9780252097997.

- ^ Cong, Xiaoping (2013). "From "Freedom of Marriage" to "Self-Determined Marriage": Recasting Marriage in the Shaan-Gan-Ning Border Region of the 1940s". Twentieth-Century China. 38 (3): 184–209. doi:10.1353/tcc.2013.0040. ISSN 1940-5065.

- ^ Cong, Xiaoping (2014). ""Ma Xiwu's Way of Judging": Villages, the Masses and Legal Construction in Revolutionary China in the 1940s". The China Journal. 72: 29–52. doi:10.1086/677050. ISSN 1324-9347.

- ^ Lovell, Julia (2020). Maoism: a global history. New York (N.Y.): Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0-525-56590-1.

- ^ a b c Mitter, Rana (2013). "Hunger in Henan". China's War with Japan (1 ed.). Penguin Books. pp. 279–280.

- ^ a b c d e f g Li, Hongshan (2024). Fighting on the Cultural Front: U.S.-China Relations in the Cold War. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. doi:10.7312/li--20704. ISBN 9780231207058. JSTOR 10.7312/li--20704.

- ^ Li, Jie (2023). Cinematic Guerillas: Propaganda, Projectionists, and Audiences in Socialist China. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231206273.