Opium trade in Yan'an Soviet

Northwestern China had a historical tradition of opium plantation and trade since the Opium Wars, despite continuous government attempts to stop it.[1] The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) was alleged to have secretly planted and exported opium in their controlled areas during the 1940s.[2] This claim has received limited attention in Chinese academia and research regarding the topic was censored,[3] and was denied by certain Chinese scholars.[4] There has been no official recognition or denial.[3]

According to Taiwanese historian Chen Yung-fa, from 1941 to 1945, around 40% of the financial income of the Communist China was from opium trade,[3] although the CCP strictly banned its consumption within their territory.[1][3][4] The plantation and sales of opium, termed the Special Commodity by the CCP, sparked fierce debates within the CCP, with Mao Zedong, Zhu De, Ren Bishi and Li Fuchun supporting it and Lin Boqu, Xie Juezai and Gao Gang strongly against it.[3]

Background

[edit]After the Xi'an incident of 1936, the CCP began to receive financial support from the Kuomintang (KMT, or the Nationalists), which was paid with fabi. From 1937 to 1939, the CCP was able to maintain financial balance with external fundings, with little need to tax their people. The New Fourth Army Incident in early 1941 greatly worsened the relationship between the two parties. The KMT financial support was cancelled, and CCP was economically blocked by the KMT-led government. Due to the blockade and financial deficit, the Communist China saw significant inflation, along with depreciation of their locally issued currencies. The inflation affected mainly the government and the army, rather than the farmers who could sustain themselves.[2] Planting and selling opium was a tradition in rural China since the Opium Wars, despite continuous government efforts to ban it.[1][2] The CCP records note that both Japanese and Nationalists built a system of massive selling and buying opium, which drove the Communists to take the same approach of collecting and selling opium, while making efforts to destroying the opium plantation in Japanese controlled areas.[1]

Organised plantation

[edit]The CCP started its plantation of opium in 1941, which was accompanied by strict bans on its sales and consumption within their controlled territories, as insisted by Mao Zedong. According to Nationalist intelligence, in 1941, most opium traded in CCP-controlled Yan'an Soviet came from Japanese controlled areas, while extensive planation of opium was observed in 1942. Farmers were encouraged to plant opium for the Communist government, while the military also participated in the plantation. Only the government was allowed to purchase the harvested opium, while private use or unauthorised sales were strictly prohibited. Experienced opium farmers were employed by the government to provide guidance for other farmers. After the financial difficulty in 1942, CCP once again banned opium plantation, which turned out slow and unsuccessful.[2]

Sales and smuggling

[edit]

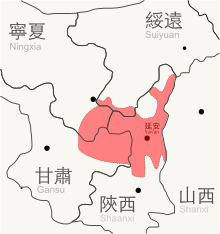

The opium in Yan'an was cultivated by local farmers using seeds supplied by the government and sold exclusively to the Communists' anti-drug agency. This agency, in turn, sold the opium to businesspeople visiting Yan'an. These traders smuggled the opium out of the Yan'an Soviet into areas such as southwestern Shanxi, southern Shaanxi, and eastern Gansu.[5] The opium was concealed in items such as salt, liquor bottles, and saddles, and was transported either under the escort of local Communist military forces or by the merchants themselves. The Communists deliberately turned a blind eye to how these merchants managed to bypass Nationalist officials and military forces stationed at the border.[3] The trade provided the Communist government with sufficient funds to procure strategic resources from the free market, supporting their financial needs.[5]

In 1946, the widespread printing of currency led to hyperinflation, prompting the Communist government to actively promote the opium trade as a means of economic support. During this period, the People's Liberation Army engaged in the sale of opium wherever they operated. By 1948, due to the severe devaluation of paper money caused by hyperinflation, the opium trade transitioned to being conducted through bartering goods instead of using currency. In 1948, only 0.67% of the opium traded in Yan'an was locally produced, a figure that declined further to just 0.03% by 1949. By this time, the financial needs of the Yan'an Soviet were sufficiently met through other sources of funding from the Communist regime, leading to the prohibition of the opium trade.[5]

Documentation

[edit]The Communists destroyed most of their official records related to the opium trade. The first known Communist documents on the subject were uncovered by Gao Long, who purchased them from an antiquities dealer. These documents, believed to have originated from archives in Xinzhou, are collectively known as the Xinzhou Opium Documents and consist of over 200 files. Unlike other records that used euphemisms to reference opium, these documents explicitly mentioned it.[6]

The opium plantation and trade was also mentioned in the 1993 edition of the Biography of Nan Hanchen, although later editions were censored to omit the relevant content. Nan Hanchen became the first director of the People's Bank of China in 1949.[3][7] In 2013, the opium trade was described by an article on Yanhuang Chunqiu, which confirms the involvement of governments and military in the opium trade and plantation.[8]

Soviet journalist Peter Vladimirov also documented his observations of opium cultivation and trade in Yan'an. On 2 August 1942, Vladimirov recorded an incident where he asked Mao Zedong why the CCP military was involved in opium production despite earlier restrictions. Mao did not respond to his query. In 1943, Vladimirov noted that Mao had appointed Ren Bishi as a special commissioner to oversee opium-related matters. Ren explained that while Mao acknowledged the moral wrongdoing of opium cultivation, he believed it was necessary under the circumstances for the opium trade to contribute to the revolution, a stance that was approved by the Politburo.[6]

The Ministry of Justice Investigation Bureau in Taiwan also holds a collection of documents on the history of the CCP. Among these is a report on opium cultivation in the Yan'an Soviet, which was compiled based on field investigations conducted by the Nationalist government's anti-drug agency.[9]

In popular culture

[edit]- In the Paradox Interactive video game Hearts of Iron IV, banning and permitting the opium trade are presented as mutually exclusive national focus options for Communist China.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Yue, Qianhou (2016). "The Trading of "Special Commodity" (Opium) in the CCP's Northwestern Shanxi Base Area during the War of Resistance against Japan". Rural China: An International Journal of History and Social Science (in Chinese) (13): 173–206.

- ^ a b c d Chen, Yung-fa (1995). "The Blooming Poppy under the Red Sun: The Yan'an Way and the Opium Trade". In Saich, Tony; Van De Ven, Hans J. (eds.). New Perspectives on the Chinese Revolution. New York, NY: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315702124-13 (inactive 2024-11-28). ISBN 9781315702124.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ a b c d e f g Chen, Yung-fa (2018). "The "Revolution Opium" of Yan'an: Mao Zedong's Secret Weapon" (PDF). Twenty-first Century (in Chinese) (8). Hong Kong: The Chinese University of Hong Kong: 43–71. ISSN 1017-5725.

- ^ a b 韩伟 (2015-06-09). "陕甘宁边区"没有发现鸦片的痕迹"". 中国社会科学报.

- ^ a b c Chen, Yao-huang (2011). "Overall Planning and Autarky: Reassessing the Economy of the Shan-Gan-Ning Border Region" (PDF). Bulletin of the Institute of Modern History, Academia Sinica (72). Taipei, Taiwan: Institute of Modern History, Academia Sinica: 137–192.

- ^ a b Yu, Jie (2019-07-12). "《顛倒民國》書摘:延安不是抗日燈塔,而是鴉片王國 -- 上報 / 評論". Up Media. New Taipei, Taiwan: Forward Media. Retrieved 2024-11-26.

- ^ "夜话中南海:以革命的名义经营鸦片贸易是毛泽东钦旨". Radio Free Asia. 2021-08-16.

- ^ "解放军建军90周年:你可能不知道的中共军史". BBC News (in Simplified Chinese). 2017-07-31. Retrieved 2024-11-26.

- ^ "台湾有一个特藏室 珍藏中共种鸦片不抗日史料". Radio France Internationale (in Simplified Chinese). 2019-05-18. Retrieved 2024-11-26.

Further reading

[edit]- Slack, Edward R. (2001). Opium, state, and society: China's narco-economy and the Guomindang, 1924 - 1937. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2361-0.