Self-induced abortion

A self-induced abortion (also called a self-managed abortion, or sometimes a self-induced miscarriage) is an abortion performed by the pregnant woman herself, or with the help of other, non-medical assistance. Although the term includes abortions induced outside of a clinical setting with legal, sometimes over-the-counter medication, it also refers to efforts to terminate a pregnancy through alternative, potentially more dangerous methods.[1] Such practices may present a threat to the health of women.[2]

Self-induced (or self-managed) abortion is often attempted during the beginning of pregnancy (the first eight weeks from the last menstrual period).[3][4] In recent years, significant reductions in maternal death and injury resulting from self-induced abortions have been attributed to the increasing availability of misoprostol (known commercially as "Cytotec").[5][6] This medication is a synthetic prostaglandin E1 that is inexpensive, widely available, and has multiple uses, including the treatment of post-partum hemorrhage, stomach ulcers, cervical preparation and induction of labor.[7] The World Health Organization (WHO) has endorsed two regimens for abortion up to 12 weeks of pregnancy using misoprostol: a standardized regimen of mifepristone and misoprostol and a regimen of misoprostol alone.[8] The regimen with misoprostol alone has been shown to be up to 83% effective in terminating a pregnancy but is more effective combined with mifepristone.[9]

Methods attempted

[edit]Women can use many different methods to self-manage (or self-induce) an abortion.[10] Some are safe and effective, while others are dangerous to the health of the woman and/or ineffective at terminating a pregnancy.

Mifepristone and/or misoprostol

[edit]The only scientifically studied effective self-induced abortion method is ingesting a combination of mifepristone and misoprostol or misoprostol alone.[8] The combination of these medications is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[11] In some countries, these pills may be available over-the-counter in pharmacies, although some pharmacies do not provide accurate instructions on use.[12] In Latin America, women have reported self-inducing abortions with misoprostol alone since the 1980s.[13] The history of women self-managing abortion with pills includes projects such as the Socorristas in Argentina and Las Libres in Mexico.[14][15] Other countries have "safe abortion hotlines", which facilitate access to pills, provide instructions on proper use of the pills, and provide emotional, logistical, and/or financial support.[16][17] Some women use online abortion pill help services such as Women on Web and Aid Access to order mifepristone and/or misoprostol, with reported effectiveness and safety in pregnancy termination and satisfaction in the service.[18][19] Instructions on abortion pill use are widely available on the websites of the World Health Organization (WHO), Gynuity Health Projects,[9] and the International Women's Health Coalition.[20]

First trimester medical abortion is highly safe and effective.[21] The side effects of medication abortion include uterine cramping and prolonged bleeding, and common side effects include nausea, vomiting and diarrhea. The majority of women who use abortion pills on their own do not need an ultrasound or a clinician, although one may be recommended to ensure that the pregnancy is not ectopic.[18] In the rare case of a complication, a woman can access a clinician skilled in miscarriage management, which is available in all countries.[19]

Studies confirm a correlation between the increase in the self-administration of medical abortion with misoprostol, and a reduction in maternal morbidity and mortality.[22] Some studies argue that unfettered access to medication abortion is a key tenet of public health, human rights, and reproductive rights.[23]

Physical trauma, herbs, and other substances

[edit]

Self-induced abortion methods vary around the world. The most commonly recorded are ingestion of plants or herbs, ingesting toxic substances, causing trauma to the uterus, causing physical trauma to the body, using alcohol and drugs in an attempt to end the pregnancy, and ingesting other substances and mixtures.[25] There are no known effectiveness studies for plants, herbs, drugs, alcohol, or other substances. These methods are more likely to cause bodily harm to the pregnant woman than to be effective in terminating a pregnancy. Causing physical trauma to a woman's body or uterus may also result in physical harm or even death to the woman instead of causing an abortion.[22]

A descriptive study of women seeking to induce abortion in Cape Town, South Africa found that the women used abortifacients from three major sources: traditional healers, illegal abortion providers, and home remedies prepared using over-the-counter ingredients. The abortifacients included assorted pills (some that were likely misoprostol, others included antiviral drugs, hypertension medication, and izifozonke), herbal blends of unclear origin, commercial herbal blends (including Stametta), "Dutch remedies" (including Vornokroy, Helmin drops, and potassium permanganate), abrasive substances, alcohol, bleach, ammonia, other household cleaners, and laxatives.[26]

Rates

[edit]As of 2019[update], an estimated 56 million abortions occurred worldwide, of which 25 million are considered by the WHO to be less safe or least safe.[27] Induced abortion is considered safe when WHO recommended methods are used by trained persons, less safe when only one of those two criteria is met, and least safe when neither is met.[28] Self-induced abortions can be safe or unsafe depending on the methods used.[29][30]

It is difficult to measure the prevalence or rate of self-induced abortions. As of 2018[update], in the United States, the estimate was that one in 10 abortions is self-induced.[31] While maternal morbidity and mortality from unsafe abortion has continued to increase due to population growth, in Latin America, from 2005 to 2012, there was a 31% decrease in the number of complications from unsafe abortion, from 7.7/1,000 to 5.3/1,000. Researchers believe that this may be due to the wide availability of misoprostol in Latin America.[32] In late 2019, it was reported that rates of self-induced abortion in the United States were rising, partly due to fears that more conservative policies would limit access to clinical abortion, and partly due to the increased availability and convenience of telehealth medical supervision and prescriptions and mail-order drugs.[33]

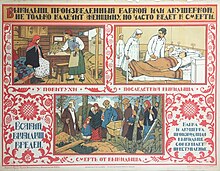

History

[edit]The practice of attempted self-induced abortion has long been recorded in the United States. Turn-of-the-20th-century birth control advocate Margaret Sanger wrote in her autobiography of a 1912 incident in which she was summoned to treat a woman who had nearly died from such an attempt.[34]

In a letter to The New York Times, gynecologist Waldo L. Fielding wrote:

The familiar symbol of illegal abortion is the infamous "coat hanger" — which may be the symbol, but is in no way a myth. In my years in New York, several women arrived with a hanger still in place. Whoever put it in – perhaps the patient herself – found it trapped in the cervix and could not remove it...However, not simply coat hangers were used. Almost any implement you can imagine had been and was used to start an abortion – darning needles, crochet hooks, cut-glass salt shakers, soda bottles, sometimes intact, sometimes with the top broken off.[35]

Charles Jewett wrote The Practice of Obstetrics in 1901. In it, he stated, "Oil of tansy and oil of rue are much relied on by the laity for the production of abortion, and almost every day one may read of fatal results attending their use. Oil of tansy in large doses is said to excite epileptiform convulsions; quite recently one of my colleagues met such a case in his practice."

In the 1994 documentary Motherless: A Legacy of Loss from Illegal Abortion, Louis Gerstley, M.D., said that, in addition to knitting needles, some women would use the spokes of bicycle wheels or umbrellas. "Anything that was metal and long and thin would be used," he stated. He stated that a common complication from such a procedure was that the object would puncture through the uterus and injure the intestines, and the women would subsequently die from peritonitis and infection. Later in the film, he mentioned that potassium permanganate tablets were sometimes used. The tablets were inserted into the vagina where they caused a chemical burn so intense that a hole may be left in the tissue. He claimed the tablets left the surrounding tissue in such a state that doctors trying to stitch up the wound couldn't do so because "the tissue was like trying to suture butter." Dr. Mildred Hanson also described the use of potassium permanganate tablets in the 2003 documentary Voices of Choice: Physicians Who Provided Abortions Before Roe v. Wade. She said, "the women would bleed like crazy because it would just eat big holes in the vagina."

Dr. David Reuben mentions that many African women use a carved wooden "abortion stick" to induce, which has often been handed down.[36]

A study concluded in 1968[37] determined that over 500,000 illegal abortions were performed every year in the United States, a portion of which were performed by women acting alone. The study suggested that the number of women dying as a result of self-induced abortions exceeded those resulting from abortions performed by another person. A 1979 study noted that many women who required hospitalization following self-induced abortion attempts were admitted under the pretext of having had a miscarriage or spontaneous abortion.[38]

WHO estimates that approximately 25 million abortions continue to be performed unsafely each year.[28] Around 7 million women are admitted to hospitals every year in developing countries[39] and between 4.7% – 13.2% of all maternal deaths can be attributed to unsafe abortion.[40] Almost every one of these deaths and disabilities could have been prevented through sexual education, family planning, and the provision of safe abortion services.[2] Abortion pills, which were first used by Brazilian women in the 1980s, can prevent many of these deaths from unsafe abortion.[41]

Law

[edit]The examples and perspective in this subsection deal primarily with the United States and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (February 2022) |

Iran

[edit]While positions regarding abortion in Islam is one open to varied interpretation by Muslim scholars, in Iran, self-induced abortion, as with other forms of abortion in general, is considered to be a haram act, in accordance a declaration by Ayatollah Khomeini that all forms of abortion are forbidden, mirroring a common position held under Shi'ite interpretation of Sharia law. As a result, a diyya of approximately 1000 dinar is issued for the abortion of male fetuses and half of that amount for female ones, though the diyya is lowered to 60 dinar[clarification needed].[42][43][44]

United States

[edit]In the United States, experts report that self-induced abortion can be medically safe but legally risky.[45] The 1973 Supreme Court decision Roe v. Wade, which was overturned in the 2022 case Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization, made abortion more readily available throughout the U.S., yet women who have abortions with pills ordered online or through non-clinical means may face risk of arrest.[46][47]

It is not common for women in the United States to be charged for the crime of self-inducing an abortion. However, a small number of people in the U.S. have been arrested for ending their own pregnancies with pills ordered online, including Purvi Patel, Jennie Linn McCormack,[48] and Kenlissia Jones.[49][50] These women were prosecuted under a variety of laws including laws directly criminalizing self-induced abortions, laws criminalizing harm to fetuses, criminal abortion laws misapplied to people who self-induce, and various laws deployed when no other legal authorization could be found.[51] In 2022, Lizelle Herrera of Texas was charged with murder after the authorities alleged that she caused "the death of an individual by self-induced abortion".[52] It was unclear whether she had an abortion herself or helped someone else with it. According to University of Texas law professor Stephen Vladeck, the state law exempts the mother from criminal homicide charges for aborting her own child.[53] On 10 April 2022, the district attorney of Texas announced that the murder charges would be dismissed.[54]

As of 2019, there are seven states with laws directly criminalizing self-induced abortion, 11 states with laws criminalizing harm to fetuses that lack adequate exemptions for the pregnant woman, and 15 states with criminal abortion laws that could be applied to women who self-induce an abortion.[55] Both the National Lawyers Guild and the American Medical Association passed resolutions condemning the criminalization of self-induced abortion.[56][57]

See also

[edit]- Abortion debate

- Feminist Abortion Network

- Gerri Santoro

- Menstrual extraction

- Our Bodies, Ourselves

- Reproductive rights

- Unsafe abortion

References

[edit]- ^ Harris LH, Grossman D (March 2020). Campion EW (ed.). "Complications of Unsafe and Self-Managed Abortion". The New England Journal of Medicine. 382 (11): 1029–1040. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1908412. PMID 32160664. S2CID 212678101.

- ^ a b Haddad LB, Nour NM (2009). "Unsafe abortion: unnecessary maternal mortality". Reviews in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2 (2): 122–126. PMC 2709326. PMID 19609407.

- ^ Worrell M. "About the 'I need an abortion' project – people on Web".

- ^ Sage-Femme Collective, Natural Liberty: Rediscovering Self-Induced Abortion Methods (2008).

- ^ Costa SH (December 1998). "Commercial availability of misoprostol and induced abortion in Brazil". International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 63 (S1): S131–S139. doi:10.1016/S0020-7292(98)00195-7. PMID 10075223. S2CID 22701113.

- ^ Faúndes A, Santos LC, Carvalho M, Gras C (March 1996). "Post-abortion complications after interruption of pregnancy with misoprostol". Advances in Contraception. 12 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1007/BF01849540. PMID 8739511. S2CID 32526547.

- ^ Goldberg AB, Greenberg MB, Darney PD (January 2001). "Misoprostol and pregnancy". The New England Journal of Medicine. 344 (1): 38–47. doi:10.1056/NEJM200101043440107. PMID 11136959.

- ^ a b World Health Organization (2018). Medical management of abortion. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/278968. ISBN 978-92-4-155040-6. OCLC 1084549520.

- ^ a b "Abortion with Self-Administered Misoprostol: A Guide for Women". Gynuity Health Projects. November 2010.

- ^ Tuttle L, Riddle JM (1995). "Contraception and Abortion from the Ancient World to the Renaissance". Sixteenth Century Journal. 26 (4): 1033. doi:10.2307/2543870. ISSN 0361-0160. JSTOR 2543870.

- ^ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ^ Footman K, Keenan K, Reiss K, Reichwein B, Biswas P, Church K (March 2018). "Medical Abortion Provision by Pharmacies and Drug Sellers in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review". Studies in Family Planning. 49 (1): 57–70. doi:10.1111/sifp.12049. PMC 5947709. PMID 29508948.

- ^ Zamberlin N, Romero M, Ramos S (December 2012). "Latin American women's experiences with medical abortion in settings where abortion is legally restricted". Reproductive Health. 9 (1): 34. doi:10.1186/1742-4755-9-34. PMC 3557184. PMID 23259660.

- ^ Zurbriggen R, Keefe-Oates B, Gerdts C (February 2018). "Accompaniment of second-trimester abortions: the model of the feminist Socorrista network of Argentina". Contraception. 97 (2): 108–115. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2017.07.170. PMID 28801052.

- ^ Singer EO (28 April 2016). "Las Libres, Guanajuato: A feminist approach to abortion within and around the law – Safe Abortion: Women's Right". Retrieved 24 August 2019.

- ^ Gerdts C, Jayaweera RT, Baum SE, Hudaya I (July 2018). "Second-trimester medication abortion outside the clinic setting: an analysis of electronic client records from a safe abortion hotline in Indonesia". BMJ Sexual & Reproductive Health. 44 (4): 286–291. doi:10.1136/bmjsrh-2018-200102. PMC 6225793. PMID 30021794.

- ^ Drovetta RI (May 2015). "Safe abortion information hotlines: An effective strategy for increasing women's access to safe abortions in Latin America". Reproductive Health Matters. 23 (45): 47–57. doi:10.1016/j.rhm.2015.06.004. hdl:11336/107662. PMID 26278832. S2CID 3567616.

- ^ a b Gomperts R, Petow SA, Jelinska K, Steen L, Gemzell-Danielsson K, Kleiverda G (February 2012). "Regional differences in surgical intervention following medical termination of pregnancy provided by telemedicine". Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 91 (2): 226–31. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0412.2011.01285.x. PMID 21950492. S2CID 9829216.

- ^ a b Gomperts RJ, Jelinska K, Davies S, Gemzell-Danielsson K, Kleiverda G (August 2008). "Using telemedicine for termination of pregnancy with mifepristone and misoprostol in settings where there is no access to safe services". BJOG. 115 (9): 1171–5, discussion 1175–8. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01787.x. PMID 18637010. S2CID 29304604.

- ^ "Abortion Using Misoprostol Pills: A Guide For All Pregnant People Seeking to Self-Manage Their Abortion". International Women's Health Coalition.

- ^ Kapp N, Eckersberger E, Lavelanet A, Rodriguez MI (February 2019). "Medical abortion in the late first trimester: a systematic review". Contraception. 99 (2): 77–86. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2018.11.002. PMC 6367561. PMID 30444970.

- ^ a b Singh S, Maddow-Zimet I (August 2016). "Facility-based treatment for medical complications resulting from unsafe pregnancy termination in the developing world, 2012: a review of evidence from 26 countries". BJOG. 123 (9): 1489–98. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.13552. PMC 4767687. PMID 26287503.

- ^ Jelinska K, Yanow S (February 2018). "Putting abortion pills into women's hands: realizing the full potential of medical abortion". Contraception. 97 (2): 86–89. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2017.05.019. PMID 28780241.

- ^ Winterhalter E (13 October 2021). "Abortion Remedies from a Medieval Catholic Nun(!)". JSTOR Daily. Retrieved 10 December 2023.

- ^ Moseson H, Herold S, Filippa S, Barr-Walker J, Baum SE, Gerdts C (2020). "Self-managed abortion: a systematic scoping review". Best Practice & Research. Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 63: 87–110. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2019.08.002. PMID 31859163.

- ^ Gerdts C, Raifman S, Daskilewicz K, Momberg M, Roberts S, Harries J (October 2017). "Women's experiences seeking informal sector abortion services in Cape Town, South Africa: a descriptive study". BMC Women's Health. 17 (1): 95. doi:10.1186/s12905-017-0443-6. PMC 5625615. PMID 28969631.

- ^ "Fact Sheet: Induced Abortion Worldwide". Guttmacher Institute. 10 May 2016.

- ^ a b Ganatra B, Gerdts C, Rossier C, Johnson BR, Tunçalp Ö, Assifi A, et al. (November 2017). "Global, regional, and subregional classification of abortions by safety, 2010-14: estimates from a Bayesian hierarchical model". Lancet. 390 (10110): 2372–2381. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31794-4. PMC 5711001. PMID 28964589.

- ^ Ngo TD, Park MH, Shakur H, Free C (May 2011). "Comparative effectiveness, safety and acceptability of medical abortion at home and in a clinic: a systematic review". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 89 (5): 360–70. doi:10.2471/blt.10.084046 (inactive 1 December 2024). PMC 3089386. PMID 21556304.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of December 2024 (link) - ^ Kiran U, Amin P, Penketh RJ (February 2004). "Self-administration of misoprostol for termination of pregnancy: safety and efficacy". Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 24 (2): 155–6. doi:10.1080/01443610410001645451. PMID 14766452. S2CID 31782566.

- ^ Grossman D, Ralph L, Raifman S, Upadhyay U, Gerdts C, Biggs A, et al. (1 May 2018). "Lifetime prevalence of self-induced abortion among a nationally representative sample of U.S. women". Contraception. 97 (5): 460. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2018.03.017.

- ^ Singh S, Maddow-Zimet I (August 2016). "Facility-based treatment for medical complications resulting from unsafe pregnancy termination in the developing world, 2012: a review of evidence from 26 countries". BJOG. 123 (9): 1489–98. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.13552. PMC 4767687. PMID 26287503.

- ^ McCammon S (19 September 2019). "With Abortion Restrictions on the Rise, Some Women Induce Their Own". NPR.

- ^ Sanger M (1938). An Autobiography. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

- ^ Fielding WL (3 June 2008). Cenicola T (ed.). "Repairing the Damage, Before Roe". The New York Times.

- ^ Reuben D (c. 1971). "Abortion". Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex* (*But Were Afraid to Ask) (17th ed.). Bantam. pp. 323–324. ISBN 0-553-05570-4.

- ^ Schwarz R (1968). Septic Abortion. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott Co.

- ^ Bose C (August 1979). "A comparative study of spontaneous and self-induced abortion cases in married women". Journal of the Indian Medical Association. 73 (3–4): 56–9. PMID 546995.

- ^ Singh S, Maddow-Zimet I (August 2016). "Facility-based treatment for medical complications resulting from unsafe pregnancy termination in the developing world, 2012: a review of evidence from 26 countries". BJOG. 123 (9): 1489–1498. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.13552. PMC 4767687. PMID 26287503.

- ^ Say L, Chou D, Gemmill A, Tunçalp Ö, Moller AB, Daniels J, et al. (June 2014). "Global causes of maternal death: a WHO systematic analysis". The Lancet. Global Health. 2 (6): e323–e333. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70227-X. hdl:1854/LU-5796925. PMID 25103301.

- ^ Zordo SD (2016). "The biomedicalisation of illegal abortion: the double life of misoprostol in Brazil". Historia, Ciencias, Saude--Manguinhos. 23 (1): 19–36. doi:10.1590/S0104-59702016000100003. PMID 27008072.

- ^ "IRAN, ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF. Law on Islamic Penalties 1991, Law No. 586. (Translation provided by the International Labour Organisation.)". Retrieved 24 November 2024.

- ^ "احکام "سقط جنین" از منظر مقام معظم رهبری". 17 September 2017.

- ^ "دیه سقط جنین چه مقدار است و به چه کسی میرسد؟". 2 December 2012.

- ^ North A (9 July 2019). "A boom in at-home abortions is coming". Vox. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- ^ "ACOG Position Statement: Decriminalization of Self-Induced Abortion". acog.org. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- ^ SIA Legal team. "Making abortion a crime (again): how extreme prosecutors attempt to punish people for abortions in the U.S." (PDF).

- ^ "Idaho Woman Arrested For Abortion Is Uneasy Case For Both Sides". NPR.org. NPR. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- ^ Paltrow LM, Flavin J (April 2013). "Arrests of and forced interventions on pregnant women in the United States, 1973-2005: implications for women's legal status and public health". Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law. 38 (2): 299–343. doi:10.1215/03616878-1966324. PMID 23262772.

- ^ Phillip A. "Murder charges dropped against Georgia woman jailed for taking abortion pills". The Washington Post.

- ^ Donovan MK (12 October 2018). "Self-Managed Medication Abortion: Expanding the Available Options for U.S. Abortion Care". Guttmacher Institute n.

- ^ Puente N (9 April 2022). "Texas woman charged with murder for 'self-induced abortion'". Nexstar Media.

- ^ "Texas woman, 26, charged with murder over 'self-induced abortion'". The Guardian. Associated Press. 9 April 2022.

- ^ Heyward G, Kasakove S (10 April 2022). "Texas Will Dismiss Murder Charge Against Woman Connected to 'Self-Induced Abortion'". The New York Times.

- ^ Rowan A (22 September 2015). "Prosecuting Women for Self-Inducing Abortion: Counterproductive and Lacking Compassion". Guttmacher Institute. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- ^ "Criminalization of Self-Induced Abortion Intimidates and Shames Women Unnecessarily". American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- ^ "Resolution Opposing the Criminalization of People's Reproductive Lives" (PDF). National Lawyers Guild. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

Further reading

[edit]- Ahiadeke C (June 2001). "Incidence of Induced Abortion in Southern Ghana". International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 27 (2): 96–108. doi:10.2307/2673822. JSTOR 2673822. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- Khokhar A, Gulati N (October 2000). "Profile of Induced Abortions in Women from an Urban Slum of Delhi". Indian Journal of Community Medicine. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- Ellertson C (March 1996). "History and efficacy of emergency contraception: beyond Coca-Cola". Family Planning Perspectives. 28 (2): 44–48. doi:10.2307/2136122. JSTOR 2136122. PMID 8777937.

- * Stephens-Davidowitz S (5 March 2016). "The Return of the D.I.Y. Abortion". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 October 2017.