Libyan crisis (2011–present)

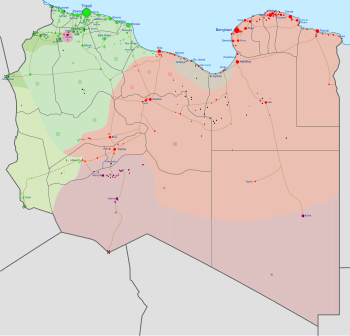

(For a more detailed map, see military situation in the Libyan Civil War)

The Libyan crisis[1][2] is the current humanitarian crisis[3][4] and political-military instability[5] occurring in Libya, beginning with the Arab Spring protests of 2011, which led to two civil wars, foreign military intervention, and the ousting and death of Muammar Gaddafi. The first civil war's aftermath and proliferation of armed groups led to violence and instability across the country, which erupted into renewed civil war in 2014. The second war lasted until October 23, 2020, when all parties agreed to a permanent ceasefire and negotiations.[6]

The crisis in Libya has resulted in tens of thousands of casualties since the onset of violence in early 2011. During both civil wars, the output of Libya's economically crucial oil industry collapsed to a small fraction of its usual level, despite having the largest oil reserves of any African country, with most facilities blockaded or damaged by rival groups.[7][8]

Since March 2022, two different governments control the country, the Tripoli-based and internationally recognized Government of National Unity, which controls the western part of the country and is led by Abdul Hamid Dbeibeh, and the House of Representatives-recognized Government of National Stability, which controls the central and eastern part of Libya and is led by Osama Hamada.[9]

Background

[edit]The history of Libya under Muammar Gaddafi spanned 42 years from 1969 to 2011. Gaddafi became the de facto leader of the country on 1 September 1969, after leading a group of young Libyan military officers against King Idris I in a nonviolent revolution and bloodless coup d'état. After the king fled the country, the Libyan Revolutionary Command Council (RCC) headed by Gaddafi abolished the monarchy and the old constitution and proclaimed the new Libyan Arab Republic, with the motto "freedom, socialism, and unity".[10]

After coming to power, the RCC government took control of all petroleum companies operating in the country and initiated a process of directing funds toward providing education, health care and housing for all. Despite the reforms not being entirely effective, public education in the country became free and primary education compulsory for both sexes. Medical care became available to the public at no cost, but providing housing for all was a task that the government was not able to complete.[11] Under Gaddafi, per capita income in the country rose to more than US$11,000, the fifth-highest in Africa.[12] The increase in prosperity was accompanied by a controversial foreign policy and increased political repression at home.[10][13]

Conflicts

[edit]First civil war

[edit]In early 2011, protests erupted with tens of thousands of Libyans taking to the streets demanding a democratic change in government as well as justice for the ones who suffered under Muammer Gaddafi's rule.[14] These peaceful protests were faced with large violent crackdowns with government troops shooting protestors and allegedly running them over with tanks.[15][16] A civil war eventually broke out. The anti-Gaddafi forces formed a committee named the National Transitional Council, on 27 February 2011. It was meant to act as an interim authority in the rebel-controlled areas. After the government began to roll back the rebels and a number of atrocities were committed by both sides,[17][18][19][20][21] a multinational coalition led by NATO forces intervened on 21 March 2011, with the stated intention to protect civilians against attacks by the government's forces.[22] Shortly thereafter, the International Criminal Court issued an arrest warrant against Gaddafi and his entourage on 27 June 2011. Gaddafi was ousted from power in the wake of the fall of Tripoli to the rebel forces on 20 August 2011, although pockets of resistance held by forces loyal to Gaddafi's government held out for another two months, especially in Gaddafi's hometown of Sirte, which he declared the new capital of Libya on 1 September 2011.[23] His Jamahiriya regime came to an end the following month, culminating on 20 October 2011 with Sirte's capture, NATO airstrikes against Gaddafi's escape convoy, and his killing by rebel fighters.[24][25]

Post-revolution armed groups and violence

[edit]The Libyan revolution led to defected regime military members who joined rebel forces, revolutionary brigades that defected from the Libyan Army, post-revolutionary brigades, militias, and various other armed groups, many composed of ordinary workers and students. Some of the armed groups formed during the war against the regime and others evolved later for security purposes. Some were based on tribal allegiances. The groups formed in different parts of the country and varied considerably in size, capability, and influence. They were not united as one body, but they were not necessarily at odds with one another. Revolutionary brigades accounted for the majority of skilled and experienced fighters and weapons. Some militias evolved from criminal networks to violent extremist gangs, quite different from the brigades seeking to provide protection.[26][27]

After the first Libyan civil war, violence occurred involving various armed groups who fought against Gaddafi but refused to lay down their arms when the war ended in October 2011. Some brigades and militias shifted from merely delaying the surrender of their weapons to actively asserting a continuing political role as "guardians of the revolution", with hundreds of local armed groups filling the complex security vacuum left by the fall of Gaddafi. Before the official end of hostilities between loyalist and opposition forces, there were reports of sporadic clashes between rival militias and vigilante revenge killings.[26][28][29]

In dealing with the number of unregulated armed groups, the National Transitional Council called for all armed groups to register and unite under the ministry of defense, thus placing many armed groups on the payroll of the government.[30] This gave a degree of legitimacy to many armed groups, including General Khalifa Haftar who registered his armed group as the "Libyan National Army", the same name he used for his anti-Gaddafi forces after the 1980s Chadian–Libyan conflict.[31]

On 11 September 2012, militants allied with Al-Qaeda attacked the US consulate in Benghazi,[32] killing the US ambassador and three others. This prompted a popular outcry against the semi-legal militias that were still operating, and resulted in the storming of several Islamist militia bases by protesters.[33][34] A large-scale government crackdown followed on non-sanctioned militias, with the Libyan Army raiding several now-illegal militias' headquarters and ordering them to disband.[35] The violence eventually escalated into the second Libyan civil war.

Second civil war and ceasefire

[edit]The second Libyan civil war[36][37] was a conflict among rival groups seeking control of the territory of Libya. The conflict has been mostly between the government of the House of Representatives, also known as the "Tobruk government", which was assigned as a result of a very low-turnout elections in 2014 and was internationally recognized as the "Libyan Government" until the establishment of GNA; and the rival Islamist government of the General National Congress (GNC), also called the "National Salvation Government", based in the capital Tripoli. In December 2015, these two factions agreed in principle to unite as the Government of National Accord.

The Tobruk government, strongest in eastern Libya, has the loyalty of Haftar's Libyan National Army and has been supported by air strikes by Egypt and the UAE.[38] The Islamist government of the GNC, strongest in western Libya, rejected the results of the 2014 election, and is led by the Muslim Brotherhood, backed by the wider Islamist coalition known as "Libya Dawn" and other militias,[39][40] and aided by Qatar, Sudan, and Turkey.[38][41]

In addition to these, there are also smaller rival groups: the Islamist Shura Council of Benghazi Revolutionaries, led by Ansar al-Sharia (Libya), which has had the support of the GNC;[42] the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant's (ISIL's) Libyan provinces;[43] as well as Tuareg militias of Ghat, controlling desert areas in the southwest; and local forces in Misrata District, controlling the towns of Bani Walid and Tawergha. The belligerents are coalitions of armed groups that sometimes change sides.[38]

Since 2015, there have been many political developments. The United Nations brokered a cease-fire in December 2015, and on 31 March 2016 the leaders of a new UN-supported "unity government" arrived in Tripoli.[44] On 5 April, the Islamist government in western Libya announced that it was suspending operations and handing power to the new unity government, officially named the "Government of National Accord", although it was not yet clear whether the new arrangement would succeed.[45] On 2 July, rival leaders reached an agreement to reunify the eastern and western managements of Libya's National Oil Corporation (NOC).[46] As of 22 August, the unity government still had not received the approval of Haftar's supporters in the Tobruk government,[47] and on 11 September the general boosted his political leverage by seizing control of two key oil terminals.[48] Haftar and the NOC then reached an agreement for increasing oil production and exports,[49] and all nine of Libya's major oil terminals were operating again in January 2017.[50]

In December 2017, the Libyan National Army seized Benghazi after three years of fighting.[51] In February 2019, the LNA achieved victory in the Battle of Derna.[52] The LNA then launched a major offensive in April 2019 in an attempt to seize Tripoli.[53] On 5 June 2020, the GNA captured all of western Libya, including the capital Tripoli.[54] The next day the GNA launched an offensive to capture Sirte.[55] However, they proved unable to advance.[56] On 21 August, the GNA and the LNA both agreed to a ceasefire. Khalifa Haftar, Field Marshal of the LNA, rejected the ceasefire and LNA spokesman Ahmed al-Mismari dismissed the GNA's ceasefire announcement as a ploy.[57][58] On 23 August, street protests took place in Tripoli, where hundreds protested against the GNA for living conditions and corruption within the government.[59]

On 23 October 2020, the UN disclosed that a permanent ceasefire deal had been reached between the two rival forces in Libya. The nationwide ceasefire agreement is set to ensure that all foreign forces, alongside mercenaries, have left the country for at least three months. All military forces and armed groups at the trenches are expected to retreat back to their camps, the UN's envoy to Libya, Stephanie Williams added.[60][61][62] The eastern city of Benghazi witnessed the landing of the first commercial passenger flight from Tripoli on the same day, which had not happened for over a year and is perceived to be an indication of success of the deal.[63]

Political instability and post-civil war fighting

[edit]On 10 March 2021, an interim unity government was formed, and the Government of National Accord was dissolved. The GNU was slated to remain in place until the next Libyan presidential election scheduled for 10 December.[64] However, the election has been delayed several times[65][66][67] since, effectively rendering the unity government in power indefinitely, causing tensions which threaten to reignite the war.

The House of Representatives, which rules eastern Libya, passed a no-confidence motion against the unity government on 21 September 2021.[68] On 3 March 2022 a rival Government of National Stability (GNS) was installed in Sirte, under the leadership of Prime Minister Fathi Bashagha.[69] The decision was denounced as illegitimate by the High Council of State and condemned by the United Nations.[70][71] Both governments have been functioning simultaneously, which has led to dual power in Libya. The Libyan Political Dialogue Forum keeps corresponding with ceasefire agreement.[9]

In 2022, fighting yet again resumed between factions of the GNU and the recently formed GNS in Tripoli. The GNS was formed to rival the GNU although the GNU saw the creation of the government as illegitimate. The GNU is considered to be the internationally-recognized government and has mainly been backed by Turkey whereas the GNS has been supported by the House of Representatives and the Libyan National Army. Fighting between the two factions escalated on August 27, 2022.[72]

Drone strikes against Wagner Group-affiliated assets near the al-Kharrouba air base near Benghazi occurred on 30 June 2023. No casualties were reported, and no group has claimed responsibility.[73] The Tripoli-based government in Libya denied involvement.[74]

Fighting restarted in August 2023.[75] In September 2023, against the backdrop of the civil war, flooding brought by Storm Daniel caused two dams collapsed in the city of Derna, in Cyrenaica, causing thousands of deaths.

On 28 June 2024, it was reported that the Libyan National Army deployed large forces on the border with Algeria and demanded to transfer 32 thousand square kilometres of disputed territories under its control, and in case of refusal - threatened with military solution of the issue.[76]

On 13 August 2024 the Benghazi parliament voted to end the term of the Tripoli-based government of Prime Minister Abdul Hamid Dbeibeh, in an attempt to dissolve the Government of National Unity and proclaim the Government of National Stability as the only legitimate government of Libya.[77][78][79] The High Council of State described the vote as void, claiming it violated the 2015 peace agreement.[79]

On 18 August 2024, The Central Bank of Libya suspended all its operations following the kidnapping of the director of its IT department by an unknown person.[80]

Socioeconomic impact

[edit]In spite of the crisis, Libya maintains one of the highest human development index (HDI) rankings among countries in Africa.[81][82] The war has caused a significant loss of economic potential in Libya, estimated at 783.2 billion Libyan dinars from 2011 to 2021.[83] By 2022, the humanitarian situation had improved, though challenges remain.[84]

See also

[edit]- Yemeni crisis (2011–present)

- Egyptian Crisis (2011–2014)

- Crisis in Venezuela (late 2000s–present)

- Iraqi conflict (2003–present)

- Turkish intervention in Libya (2020–present)

References

[edit]- ^ "Libya – Crisis response", European Union.

- ^ Fadel, L. "Libya's Crisis: A Shattered Airport, Two Parliaments, Many Factions". Archived 2015-04-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Libya: humanitarian crisis worsening amid deepening conflict and COVID-19 threat - UNHCR

- ^ War and pandemic compound Libya’s humanitarian crisis - The Arab Weekly

- ^ Post-Gadhafi Libya: Crippled by continuous clashes, political instability - Daily Sabah

- ^ Zaptia, Sami (2020-10-23). "Immediate and permanent ceasefire agreement throughout Libya signed in Geneva". Libya Herald. Archived from the original on 2020-10-23. Retrieved 2020-10-23.

- ^ a b "Country Analysis Brief: Libya" (PDF). US Energy Information Administration. 19 November 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 December 2015. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- ^ "President Obama: Libya aftermath 'worst mistake' of presidency". BBC. 11 April 2016. Archived from the original on 21 April 2016. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- ^ a b "Libya — a tale of two governments, again". Arab News. 2022-06-11. Retrieved 2022-08-28.

- ^ a b "Libya: History". GlobalEDGE (via Michigan State University). Archived from the original on 20 June 2010. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- ^ "Housing". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 28 November 2011. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- ^ "African Countries by GDP Per Capita > GDP Per Capita (most recent) by Country". NationMaster. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 24 July 2011.

- ^ Winslow, Robert. "Comparative Criminology: Libya". Crime and Society. San Diego State University. Archived from the original on 7 August 2011. Retrieved 24 July 2011.

- ^ Black, Ian (2011-02-17). "Libya cracks down on protesters after violent clashes in Benghazi". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2024-03-07.

- ^ Black, Ian; Bowcott, Owen (2011-02-18). "Libya protests: massacres reported as Gaddafi imposes news blackout". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2024-03-07.

- ^ "Gaddafi: What now for Libya’s dictator, and where does Britain". The Independent. 2011-02-20. Retrieved 2024-03-07.

- ^ Smith, David (12 September 2011). "Murder and torture 'carried out by both sides' of uprising against Libyan regime". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 17 November 2016. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- ^ "War Crimes in Libya". Physicians for Human Rights. Archived from the original on 15 October 2016. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- ^ Crawford, Alex (23 March 2011). "Evidence of Massacre by Gaddafi Forces". Sky News. Archived from the original on 21 June 2013.

- ^ "Pro-Gaddafi tanks storm into Libya's Misurata: TV". Xinhua. 6 March 2011. Archived from the original on 15 March 2012. Retrieved 25 October 2011.

- ^ Fahim, Kareem; Kirkpatrick, David D. (23 February 2011). "Qaddafi's Grip on the Capital Tightens as Revolt Grows". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 7 August 2011. Retrieved 25 October 2011.

- ^ "NATO Launches Offensive Against Gaddafi". France 24. Archived from the original on 13 May 2011.

- ^ "Libya crisis: Col Gaddafi vows to fight a 'long war'". BBC News. 1 September 2011. Archived from the original on 13 October 2018. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ^ Vlasic, Mark (2012). "Assassination & Targeted Killing – A Historical and Post-Bin Laden Legal Analysis". Georgetown Journal of International Law: 261.

- ^ "Col Gaddafi killed: convoy bombed by drone flown by pilot in Las Vegas". The Daily Telegraph. 20 October 2011. Archived from the original on 21 March 2017. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- ^ a b Chivvis, Christopher S.; Martini, Jeffrey (2014). Libya After Qaddafi: Lessons and Implications for the Future (PDF). RAND Corporation. pp. 13–16. ISBN 978-0-8330-8489-7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-12-09. Retrieved 2016-11-24.

- ^ McQuinn, Brian. After the Fall: Libya's Evolving Armed Groups.

- ^ Kirkpatrick, David D. (1 November 2011). "In Libya, Fighting May Outlast the Revolution". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 17 November 2011. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- ^ Meo, Nick (31 October 2011). "Libya: revolutionaries turn on each other as fears grow for law and order". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 16 November 2011. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- ^ Wehrey, Frederic (24 September 2014). "Ending Libya's Civil War: Reconciling Politics, Rebuilding Security". Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Archived from the original on 30 November 2016. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- ^ Abuzaakouk, Aly (8 August 2016). "America's Own War Criminal in Libya". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 30 November 2016. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- ^ Schuchter, Arnold (2015). Isis Containment & Defeat: Next Generation Counterinsurgency. iUniverse.

- ^ Hauslohner, Abigail (24 September 2012). "Libya militia leader: Heat-seeking missiles, other weapons stolen during firefight". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 24 September 2012. Retrieved 25 September 2012.

- ^ "Libyan demonstrators wreck militia compound in Benghazi". Al Arabiya. 21 September 2012. Archived from the original on 24 September 2012. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- ^ "Libyan forces raid militia outposts". Al Jazeera. 23 September 2012. Archived from the original on 24 September 2012. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- ^ "Libya's Second Civil War: How did it come to this?". Conflict News. Archived from the original on 20 March 2015. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ^ "Stabilizing Libya may be the best way to keep Europe safe". National Post. 24 February 2015. Archived from the original on 25 February 2015. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ^ a b c Stephen, Chris (29 August 2014). "War in Libya – the Guardian briefing". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 29 March 2015. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- ^ "Libya's Legitimacy Crisis". Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. 20 August 2014. Archived from the original on 28 January 2015. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- ^ "That it should come to this". The Economist. 10 January 2015. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- ^ "Bashir says Sudan to work with UAE to control fighting in Libya". Ahram Online. 23 February 2015. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- ^ "Omar Al-Hassi in "beautiful" Ansar row while "100" GNC members meet". Libya Herald. 18 November 2014. Archived from the original on 3 February 2015. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ^ "Why Picking Sides in Libya won't work". Foreign Policy. 6 March 2015. Archived from the original on 25 February 2017. Retrieved 8 March 2017. "One is the internationally recognized government based in the eastern city of Tobruk and its military wing, Operation Dignity, led by General Khalifa Haftar. The other is the Tripoli government installed by the Libya Dawn coalition, which combines Islamist militias with armed groups from the city of Misrata. The Islamic State has recently established itself as a third force"

- ^ "Libya's unity government leaders in Tripoli power bid". BBC News. 31 March 2016. Archived from the original on 2018-07-18. Retrieved 2018-06-21.

- ^ Elumami, Ahmed (5 April 2016). "Libya's self-declared National Salvation government stepping down". Reuters. Archived from the original on 8 April 2016. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- ^ "Libya Oil Chiefs Unify State Producer to End Row on Exports". Bloomberg News. 3 July 2016. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- ^ Shennib, Ghaith (22 August 2016). "Libya's East Rejects Unity Government in No-Confidence Vote". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on 20 March 2017. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- ^ Alexander, Caroline; Shennib, Ghaith (12 September 2016). "Libya's Oil Comeback Derailed as Former General Seizes Ports". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on 16 January 2017. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- ^ El Wardany, Salma (16 November 2016). "Libya to Nearly Double Oil Output as OPEC's Task Gets Harder". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- ^ Sarrar, Saleh; El Wardany, Salma (4 January 2017). "Libyan Oil Port Said to Re-Open as OPEC Nation Boosts Output". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on 5 January 2017. Retrieved 6 January 2017.

- ^ "Libyan army takes over remaining militant stronghold in Benghazi". Xinhua News Agency. Archived from the original on 2018-01-02. Retrieved 2019-08-18.

- ^ "Eye On Jihadis in Libya Weekly Update: February 12". libyaanalysis. 2019-02-13. Archived from the original on 2019-03-28. Retrieved 2019-03-28.

- ^ "Khalifa Haftar, Libya's strongest warlord, makes a push for Tripoli". The Economist. 5 April 2019. ISSN 0013-0613. Archived from the original on 5 April 2019. Retrieved 5 April 2019.

- ^ "Libyan government says it has entered Haftar stronghold Tarhouna". Reuters. 5 June 2020. Archived from the original on June 5, 2020. Retrieved 5 June 2020 – via uk.reuters.com.

- ^ "Libya's GNA says offensive launched for Gaddafi's hometown of Sirte". Middle East Eye. 6 June 2020. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ Libya: Haftar's forces 'slow down' GNA advance on Sirte. Published 11 June 2020.

- ^ "Libya's Tripoli-based government and a rival parliament take steps to end hostilities". Reuters. 21 August 2020.

- ^ "UN urges probe after 'excessive use of force' at Tripoli protest". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ "Protests against Libya's GNA erupt in Tripoli over living conditions". Arab News. 23 August 2020. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ "'Historic' Libya cease-fire agreed, UN says". Deutsche Welle.

- ^ "Libya's rival forces sign permanent ceasefire at UN-sponsored talks". TheGuardian.com. 23 October 2020.

- ^ "Libya rivals sign ceasefire deal in Geneva". BBC News. 23 October 2020.

- ^ "UN says Libya sides reach 'permanent ceasefire' deal". www.aljazeera.com.

- ^ "Libyan lawmakers approve gov't of PM-designate Dbeibah". Al Jazeera. 10 March 2021. Retrieved 10 March 2021.

- ^ "Libya electoral commission dissolves poll committees". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- ^ "UN: Libya elections could be held in June". Africanews. 17 January 2022. Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- ^ "Libya's PM Dbeibah proposes holding polls at end of 2022". Daily Sabah. 2022-05-26. Retrieved 2022-06-14.

- ^ "Libya's parliament passes no-confidence vote in unity government". Al Jazeera. 21 September 2021. Retrieved 20 October 2021.

- ^ Assad, Abdulkader (3 March 2022). "Bashagha's government sworn in at House of Representatives in Tobruk". The Libya Observer.

- ^ Alharathy, Safa (1 March 2022). "HCS: Granting confidence to a new government violates Political Agreement". The Libya Observer.

- ^ "UN voices concern over vote on new Libyan prime minister". Al Jazeera. 3 March 2022.

- ^ "Libya clashes: UN calls for ceasefire after 32 killed". BBC News. 2022-08-28. Retrieved 2022-08-28.

- ^ "Drone strikes target Wagner base In Libya: military source". Africanews. 2023-06-30. Retrieved 2023-06-30.

- ^ "Libya: Tripoli denies involvement in drone strikes in east". Africanews. 2023-06-30. Retrieved 2023-06-30.

- ^ Alhenawi, Ruba (2023-08-16). "At least 55 dead following clashes between rival factions in Libya". CNN. Retrieved 2023-08-17.

- ^ "The Libyan National Army has deployed large forces on the border with Algeria and is demanding that 32,000 square kilometres of disputed territory be transferred to its control". Nigroll. Retrieved 29 June 2024.

- ^ "Libyan parliament ends term of Tripoli-based govt". TRT World. 13 August 2024.

- ^ "Libyan parliament ends term of Dbeibah-led unity government". Daily Sabah. 13 August 2024.

- ^ a b Mahmoud, Khaled (14 August 2024). "Libyan Parliament Unilaterally Ends Terms of Presidential Council, GNU". Asharq Al-Awsat.

- ^ "Libya's central bank suspends operations after kidnapping of official". Reuters. 18 August 2024. Retrieved 19 August 2024.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2021-22: Uncertain Times, Unsettled Lives: Shaping our Future in a Transforming World" (PDF). hdr.undp.org. United Nations Development Programme. 8 September 2022. pp. 272–276. ISBN 978-9-211-26451-7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 September 2022. Retrieved 3 December 2022.

- ^ "Top 10 Most Developed Countries in Africa - 2021/22 HDI*". World Population Review. Retrieved 13 September 2023.

- ^ "The economic cost of the Libyan conflict (September 2021) [EN/AR] - Libya". ReliefWeb. 28 September 2021. Retrieved 2023-02-27.

- ^ "The World Bank in Libya". World Bank. 4 April 2023. Retrieved 13 September 2023.