Saint-Sauveur Abbey Church of Redon

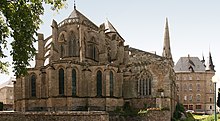

Choir and transept of the Saint-Sauveur abbey church, with the "duke's chapel" in the foreground, located along the north aisle. | |

| |

| 47°39′02″N 2°05′01″W / 47.65056°N 2.08361°W | |

| Location | Redon, Ille-et-Vilaine, France |

|---|---|

| Type | Parish church with Gothic and Romanesque style |

| Height | Bell tower: 57 meters; Romanesque tower: 27 meters |

| Beginning date | 11th century |

| Dedicated date | Redon Abbey |

The Saint-Sauveur Abbey Church is a Catholic church situated in Redon, in the French department of Ille-et-Vilaine, in the Brittany region. The church is located to the north of the former Saint-Sauveur Abbey of Redon, where it served as the abbey church until 1790. At that time, the abbey was suppressed, and the church was then assigned to the parish. The monastic buildings subsequently became a high school.

Construction started in the 11th century. From that period, the Romanesque nave remains, although five bays shortened it after a fire in 1780. The transept, constructed in the 12th century, is particularly noteworthy. Its crossing is reminiscent of contemporary structures in southwestern France, while the apse dates from the latter half of the 13th century. Its construction follows the very unified and rigorous principles of the Redon Gothic architecture of Île-de-France. The bell tower was constructed after the apse to create a monumental facade. The project was ultimately unfinished, leaving only the bell tower, which was separated from the church during the 1780 fire. A chapel was subsequently constructed on the north side of the apse, built around the mid-15th century for Duke Francis I of Brittany.

The church was designated a historical monument in the 1862 list, and the bell tower was similarly classified in 1875. It houses many historical monuments, including the tomb of Duke Francis I of Brittany. It also contains a Baroque retable in the choir, situated around the high altar. Two organs are also present: the great organ and the choir organ.

Location

[edit]The church is situated on the north side of the Saint-Sauveur Abbey of Redon, near the town hall.

History

[edit]The construction of the church

[edit]The abbey was founded in 832 and had a church built around 848, dedicated to Saint Stephen, located to the east of the current building. The Normans ravaged it, and it was later rebuilt for the first time by Abbot Ritcand (868-871) at the current location. Some parts of the north wall of the nave and the northern arm of the transept may date from this period.[1] The new church was again destroyed, along with the monastery, by a second Norman raid in 920. The monks then left the abbey and wandered for several years in the Loire Valley, Burgundy, and Poitou.[2]

The church was rebuilt again in the first half of the 11th century according to the principles of Romanesque architecture. It was one of the most imposing in the Duchy of Brittany and featured an apse with an ambulatory and radiating chapels. Around the mid-12th century, the crossing tower was constructed, inspired by prestigious buildings in Aquitaine.[3]

In 1230, a fire caused severe damage to the Romanesque building. King Henry III of England and the Pope encouraged the church's reconstruction. However, a conflict between Duke John I of Brittany and the monks resulted in the latter's exile, which delayed the construction start. The monks returned in 1256, and construction began in 1260-1270. By 1276, the lower parts of the central nave and the radiating chapels were well advanced, as evidenced by the receipt of a crucifix and two silver statues of the Virgin and Saint John for the high altar. The upper parts were probably completed or nearing completion around 1300, as evidenced by the presence of stained glass in the high windows representing Dukes John I and also John II of Brittany, which were installed in the 17th century.[4]

Construction resumed approximately a decade later at the western end of the building. The objective was to replace the Romanesque facade with a more substantial one. However, only the north tower was constructed, probably completed when the War of the Breton Succession started in 1341. The triumph of the Montfort faction resulted in the establishment of a ducal chapel in the abbey church, dedicated to Our Lady of Good News, more commonly referred to as the "ducal chapel," around 1440.[5]

The abbey church after the Middle Ages

[edit]

In the 1640s, the Benedictines of Saint-Maur assumed control of the abbey and initiated a program of reconstruction and modification. Among the changes implemented was the construction of a shed roof above the ambulatory, which blocked the triforium at the round part while leaving it open in the straight bays. Additionally, a large retable was installed in the choir around the high altar.[5]

In 1780, a fire devastated the abbey church, resulting in the nave being shortened by five bays. This explains its separation from the Gothic tower, which was originally located at the facade. Furthermore, the nave vault was lowered, which led to the removal of the side windows and explains the lack of light inside.[3]

In 1790, the abbey was suppressed. However, the church continued to be used for worship until 1794, when it was converted into a Temple of the Supreme Being. It was then returned to Catholic worship under the First Empire.[6]

On November 10, 1799, Redon was taken by the Chouans after battles against the Republican garrison entrenched inside the abbey church.[7] On June 4, 1815, the Chouans again captured the town but, lacking cannons, they could not dislodge the imperial soldiers entrenched in the abbey tower.[8]

The edifice was designated a historical monument in 1862 for the church and in 1875 for the bell tower.[9] The latter underwent restoration in 1898.[2] The church was restored in 1910, and the alterations introduced by the Maurists were subsequently removed.[5] An excavation campaign conducted between 1913 and 1914 did not yield any relics or evidence of pilgrimage.[2]

The abbey church in the 21st century

[edit]Since the French Revolution, the Saint-Sauveur Abbey Church of Redon has been a parish church, belonging in 2019 to the parish of Saint-Conwoion in the Pays de Redon. Mass is celebrated there every Sunday at 10:30 am.[10] In September 2019, it hosted an exhibition on the theme of the pilgrimage to Saint James of Compostela.[11]

Architecture

[edit]Facade

[edit]

Before the 1780 fire, the facade of the building exhibited only the north tower, which was constructed as a separate structure from the outset. The initial project likely included another tower at the opposite end of the facade, which would have mirrored the north tower.[12]

The tower is constructed from the same granite as the apse and exhibits a similar decorative scheme, comprising smooth basket capitals, false arcatures applied on three sides, and decorated with trefoils and quatrefoils. However, at the bell stage, two friezes of quatrefoils with angular traces, one at the base and the other at the top, as well as the rebated cordon at the base of the windows, rather reflect the art of the early 14th century. The different stages are served by a rectangular turret located at the southwest corner of the tower, containing a spiral staircase.[13]

On the south wall of the tower, three doors remain unconnected to the proposed monumental facade. At the base of the tower, wall ribs were intended to support the aisles of the Romanesque nave; they rest on corbels shaped like inverted cones, of English origin, also observed at the same period in the transept of Notre-Dame de Guingamp. Other decorative elements indicate a kinship with the church of Guingamp, including capitals with stylized foliage and applied decoration. The entire spire, devoid of guardrails but opened by small dormers and adorned with eight-sided ridge turrets, is also similar to the Guingamp edifice.[14]

The former facade, depicted in a 17th-century engraving, was a relatively simple triangular gable wall, supported by buttresses at the corners.[15]

Nave

[edit]

Constructed in the 11th century, the nave has three aisles. It is six bays long, but the initial construction was longer, having twelve bays. The five western bays were destroyed by the fire in 1780. The remaining structure is still 21 meters long. The elevation of the central nave initially had two levels: large arcades and high windows that allowed light to illuminate the nave. However, the 1780 fire necessitated lowering the vault and eliminating these windows, rendering the nave quite dark. Only the semicircular arches remain, with their simple arches falling onto simply chamfered abaci. These abaci rest on very thin, plain capitals, which were reshaped after the fire to give a Doric style to the plaster-covered ensemble. The capitals crown half-columns attached to square piers that predate them.[1]

The north wall of the nave's collateral, the north transept wall, and the base of the south collateral are partially constructed with small cubic stonework, featuring flat stone courses and herringbone bonds. Some scholars posit that this architectural style may be a relic of the Carolingian church, or at the very least, a precursor to the Romanesque construction.[1]

Transept

[edit]

The nave opens into a transept with prominent arms. The four piers of the lower level of the transept crossing date back to the 11th century. They support a large dome on squinches. Each pier is topped with capitals that are the only remaining Romanesque capitals inside the church: two per pier inside the transept and two more on the side facing the nave. The capitals are carved in the shape of Corinthian baskets but decorated with particularly stylized volutes or vegetation, sometimes featuring a triangular mask. On the southern capital of the northeast pier, this mask has transformed into a human figure. This decoration is highly symmetrical.[16]

The crossing tower was constructed in the 12th century, likely between 1100 and 1130.[17] It comprises three levels. The first level is blind, with walls adorned with blind arcades, some of which rest on columns with capitals. The middle level is slightly recessed and features a series of open arcatures with rounded corners. Finally, the upper level, which is further recessed from the middle level, is open with a series of lower arcades than those on the middle level. In addition to the open and blind arcatures, the tower is decorated with irregularly placed stones of different colors in medium ashlar. This crossing tower is unique in Brittany[1] and is inspired by Aquitaine models.[3] The capitals on the second level feature compositions of leaves, scrolls, or interlaces reminiscent of those at the Sainte-Croix Abbey in Quimperlé. However, they are highly damaged, suggesting that they may have been carved by restorers based on those at Quimperlé.[16]

Chevet

[edit]

The chevet consists of three straight bays, followed by a five-sided apse, all surrounded by an ambulatory with five radiating chapels. On either side of the first bays of the ambulatory, two three-bay aisles house rectangular chapels. The entire structure is vaulted with quadripartite ribs. The width of the straight bays of the choir decreases as one moves toward the apse, which suggests that the Gothic building was likely constructed on the foundations of the Romanesque church.[5]

From the exterior, the chevet appears as a particularly harmonious pyramidal composition, reminiscent of the chevet of the Basilica of Saint-Denis, redesigned between 1230 and 1260. The tangent radiating chapels form a unified crown with the undulating contours of the chevet further enhanced by the glazed triforium, which serves to unify the ensemble. This glazed band, which extends from one side of the chevet to the other, is continuous and never interrupted. The upper level is characterized by high windows with trefoil tracery. The entire structure is crowned by a guard rail featuring a frieze of quatrefoils.[18] Internally, the elevation comprises three levels: large double-roll arcades descend onto piers comprising four half-columns via smooth basket capitals; a large openwork triforium occupies the middle level; finally, wide high windows illuminate the building. The windows of the first two straight bays are composed of three lancets intersecting at the top of the bay, influenced by English architecture. Those of the apse consist of lancets topped with trefoils. The overall effect is very sober, corresponding well to the movement of simplification in Rayonnant Gothic architecture in the last third of the 13th century.[18]

The "Chapelle au Duc" and the Chapel of Saint Roch

[edit]The north aisle of the chevet is home to the "Chapelle au Duc," which was named after Duke Francis I, a patron of the abbey and was buried there in 1450. The chapel consists of three bays, with the northernmost bay illuminated by a window with three lancets and a network of bellows and mouchettes. A single window lights the eastern side of the chapel. The walls are supported by strong buttresses that join in machicolated arches. The walkway originally connected to the rest of the chevet to the east and the city wall to the west. However, the Maurists replaced it with a shed roof.[19]

After the north transept is a diminutive rectangular chapel of reduced dimensions, which is dedicated to Saint Roch and was constructed during the 16th century.[19]

Furniture

[edit]The high altar

[edit]

The high altar of the abbey was donated by Cardinal Richelieu between 1634 and 1636 when the abbey belonged to the congregation of Saint-Maur. It was crafted by the sculptor Caris Tugal and is particularly monumental, consisting of an altar surmounted by three stone figures. Around this altar, a rather imposing base supports four Corinthian capitals that frame a large panel and support a curved cornice. Above, four additional Corinthian capitals encircle a niche that contains another statue. A sculpted pediment crowns the ensemble. On August 30, 1907, the entire structure was designated a historical monument.[20]

The central statue situated above the altar is representative of the virtue of Faith. It was once equipped with a ciborium, which served as a suspended Eucharistic reserve.[21]

Other retables

[edit]In addition to the monumental altarpiece of the high altar, two additional retables are located in the first chapels on the north and south sides of the ambulatory. Both were constructed of marble around the mid-17th century during the Maurist period. They exhibit a structural similarity to the high altar, with a base supporting four columns topped with Corinthian capitals, which frame a large central painting and two niches on either side. The upper portion of the altarpiece is supported by an entablature with a sculpted frieze, which is flanked by small columns that frame a niche. A curved cornice supported by caryatids crowns the ensemble. Both altarpieces were listed as historical monuments on August 30, 1907, similar to the high altar.[22][23]

Paintings

[edit]The Saint-Sauveur church contains three paintings that have been designated historical monuments since May 14, 1984. These include an Adoration of the Shepherds, dated to the first quarter of the 17th century, and two other paintings that depict the Virgin Mary and the Child Jesus, both from the 17th century. All three paintings are painted on canvas, and the Virgin and Child have their frame.[24][25]

-

Altarpiece.

-

Rosary altarpiece.

Statues

[edit]

The Saint-Sauveur Abbey houses some statues and statue elements. The oldest is a statue of the Madonna in polychrome and gilded stone, dating from the 15th century. It was listed as a historical monument on April 9, 1999.[26] A walnut wood head of Christ kept in the sacristy likely comes from a 17th-century crucifix. The statue was listed as a historical monument on May 14, 1984.[27] Finally, a Virgin and Child statue, made of silver-plated metal on a pearwood core, was created in the first quarter of the 19th century. It was also listed as a historical monument on May 14, 1984.[28]

The baptismal fonts

[edit]The baptismal fonts were designated as historical monuments on May 14, 1984. The set comprises a marble basin from the second half of the 19th century, closed by a copper lid and surrounded by a wrought iron grille from the 20th century.[29]

The holy water font

[edit]In the northern arm of the transept, a dismounted capital has been transformed into a holy water font. Sculpted on three of its four faces, the capital features Corinthian shapes and decorations. It consists of three registers: a collar of foliage, topped by larger leaves, trilobed on the central face and simple on the sides; above, two bound stems grow into volutes at the angles and center of the basket. This capital probably originated from the apse of the Romanesque chevet of the church.[16]

The tombs

[edit]The church contains two tombs that have been designated as historical monuments. The tomb of Duke Francis I, who died in 1450, is located in a chapel to the southeast of the choir. It comprises a stone sarcophagus that has been decorated with moldings and panels carved with escutcheons, the arms of which are no longer visible. Above the moldings, an ogee arch is surmounted by an openwork gallery. This item has been designated a historical monument since August 30, 1907.[30]

In the axial chapel, there is the tomb of Raoul de Pontbriand, abbot of Saint-Sauveur, who passed away in 1422. The sarcophagus, situated within an arched recess, is embellished with six panels bearing escutcheons. However, the arms depicted on these escutcheons have been obliterated. The slab that once covered the tomb bore an effigy of the abbot, which has since been lost. The recess is surmounted by an ogee arch with trefoils and crockets, which is then followed by a frieze of escutcheons in carved panels. The entire structure has been listed as a historical monument since August 30, 1907, similar to the duke's tomb.[31]

Bell tower

[edit]Old bells and the conflict with the town

[edit]In the 15th century, a bell with a clock was installed in the abbey's tower. Its status was unclear until the 17th century when it was determined that the town only had the use of the clock and was not its owner. About twenty years later, in 1690, the bell-ringers broke the two bells, which the monks replaced. A further breakage of the bells in 1709 led to the replacement of the two broken instruments with three others to avoid overuse of the bells, which were used both to mark the hours and to ring the offices. Another bell breakage in 1740 resulted in a conflict between the monks and the town over the use of the bells. The bells were reinstalled the following year but were not used until an agreement was reached in 1761.[32]

Current bell towers

[edit]In 2019, the bell tower housed six bells dating from the first half of the 20th century. Three of these were named Hyacinthe, Marie-Ursule, and Thérèse de l'Enfant-Jésus. Each of these bells displayed the town's coat of arms, along with an image of Christ.[33]

Organs

[edit]The Saint-Sauveur abbey has two organs: a great organ and a choir organ.

Old organs

[edit]The organ in the abbey is documented as early as 1490, with the hiring of François Tayart to oversee its maintenance. In 1636, the organ suffered from rodent infestations that gnawed at some parts. The monks then commissioned Nicolas Tribolle, an organ builder, to repair the positive organ and the pedal keyboard. The aforementioned document provides insight into the composition of these parts of the organ, which were destroyed in the fire of 1780 and subsequently replaced in 1841 by an instrument ordered from the company Le Maresquier and completed by Le Logeais:[34]

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

The great organ

[edit]

The great organ was constructed in 1901 by Louis Debierre and subsequently restored by Yves Sévère in 1976. The organ's composition is as follows:[34]

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||

The transmission is mechanical, with a pneumatic machine for the great organ. The console is separate but not reversed.

The Choir Organ

[edit]

The choir organ was manufactured by the Merklin-Gutschenritter company and replaced a worn-out harmonium in 1910. Following interventions by Gaudu in 1935 and Wolf in 1950, it underwent a profound modification by Yves Sévère in 1967. Its composition is as follows:[35]

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||

The transmission is mechanical for the manual keyboards and pneumatic for the pedalboard. The instrument, housed in a neo-Gothic case (work by Harel, sculptor in Redon), is placed on the ground in an arcade to the right of the choir. A reversed console operates it.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Tillet 1982, p. 77

- ^ a b c Autissier 2005, p. 324

- ^ a b c Bonnet & Rioult 2010, p. 352

- ^ Bonnet & Rioult 2010, pp. 352–353

- ^ a b c d Bonnet & Rioult 2010, p. 353

- ^ Tillet 1982, p. 75

- ^ Souben 1989, pp. 79–85

- ^ Lignereux 2015, p. 169

- ^ "Église Saint-Sauveur (ancienne basilique)". Notice No, PA00090666, on the open heritage platform, Mérimée database, French Ministry of Culture (in French). Archived from the original on July 24, 2022.

- ^ "Horaires des messes de la paroisse | Paroisses St-Conwoïon et St-Melaine en pays de Redon" (in French). Archived from the original on September 17, 2022. Retrieved September 27, 2019.

- ^ "Paroisses St-Conwoïon et St-Melaine en pays de Redon Évènements en septembre 2019" (in French). Archived from the original on June 19, 2024. Retrieved September 27, 2019.

- ^ Bonnet & Rioult 2010, p. 361

- ^ Bonnet & Rioult 2010, pp. 361–362

- ^ Bonnet & Rioult 2010, p. 362

- ^ Tillet, Louise-Marie (1982a). Bretagne romane. La Nuit des Temps (in French). Vol. 52. La Pierre-Qui-Vire: Zodiaque. pp. 73–79.

- ^ a b c Autissier 2005, p. 325

- ^ Autissier 2005, p. 326

- ^ a b Bonnet & Rioult 2010, pp. 358–359

- ^ a b Bonnet & Rioult 2010, p. 360

- ^ "Autel, retable (maître-autel)". www.pop.culture.gouv.fr (in French). Archived from the original on April 22, 2022. Retrieved August 8, 2019.

- ^ Macé de Lépinay 1987, p. 291-305

- ^ "Autel, retable". www.pop.culture.gouv.fr (in French). Archived from the original on September 17, 2022. Retrieved August 8, 2019.

- ^ "Autel, retable". www.pop.culture.gouv.fr (in French). Archived from the original on September 17, 2022. Retrieved August 8, 2019.

- ^ "Tableau : Adoration des Bergers". www.pop.culture.gouv.fr (in French). Archived from the original on September 17, 2022. Retrieved August 9, 2019.

- ^ "Deux tableaux et leurs cadres : Vierge et Enfant Jésus". www.pop.culture.gouv.fr (in French). Archived from the original on November 29, 1998. Retrieved August 29, 2019.

- ^ "Statue : Vierge à l'Enfant". www.pop.culture.gouv.fr (in French). Archived from the original on September 17, 2022. Retrieved August 29, 2019.

- ^ "Fragment de statue : Tête de Christ". www.pop.culture.gouv.fr (in French). Archived from the original on September 17, 2022. Retrieved August 29, 2019.

- ^ "statue (statuette) : Vierge à l'Enfant". www.pop.culture.gouv.fr (in French). Archived from the original on September 17, 2022. Retrieved August 29, 2019.

- ^ "Fonts baptismaux, leur couvercle et clôture des fonts baptismaux (grille)". www.pop.culture.gouv.fr (in French). Archived from the original on September 17, 2022. Retrieved August 29, 2019.

- ^ "Tombeau de François Ier, duc de Bretagne". www.pop.culture.gouv.fr (in French). Archived from the original on September 17, 2022. Retrieved August 3, 2019.

- ^ "Tombeau de Raoul de Pontbriand". www.pop.culture.gouv.fr (in French). Archived from the original on October 14, 2019. Retrieved August 3, 2019.

- ^ "Une très longue querelle des cloches". redon.maville.com (in French). Retrieved August 9, 2019.

- ^ Gautret, Léo (April 20, 2019). "Redon. Quand la ville vivait au rythme de ses cloches". Ouest-France.fr (in French). Archived from the original on November 29, 1998. Retrieved August 9, 2019.

- ^ a b "Orgues de Redon: Grand-Orgue de l'Abbatiale Saint-Sauveur". Orgues de Redon (in French). Archived from the original on August 17, 2022. Retrieved August 9, 2019.

- ^ Morvézen, Sabine (2006). Orgues en Ille-et-Vilaine. Inventaire national des orgues (in French). Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes. p. 205. ISBN 2-7535-0153-X.

Bibliography

[edit]- Autissier, Anne (2005). La sculpture romane en Bretagne : xie – xiie siècles (in French). Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes. pp. 323–326. ISBN 2-7535-0066-5.

- Bonnet, Philippe; Rioult, Jean-Jacques (2010). "Redon. Abbaye Saint-Sauveur". Bretagne gothique (in French). Paris. pp. 352–364. ISBN 978-2-7084-0883-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Déceneux, Marc (1998). La Bretagne romane (in French). Édilarge. pp. 37–39. ISBN 978-2-7373-2262-4.

- Gallet, Yves (2006). "Opus anglicanum, opus francigenum ? Le chevet de l'abbatiale de Redon et la diffusion du gothique rayonnant en Bretagne". Architektur und Monumentalskulptur des 12.-14. Jahrhunderts, Festschrift Peter Kurmann (in French). Berne: Peter Lang. pp. 143–161.

- Macé de Lépinay, François (1987). "Contribution à l'étude des suspensions eucharistiques au xviiie siècle : À propos de quelques statues de la foi conservées en Bretagne". Bulletin monumental (in French): 291–305. ISSN 2275-5039. Archived from the original on June 19, 2024.

- Lignereux, Aurélien (2015). Chouans et Vendéens contre l'Empire, 1815. L'autre Guerre des Cent-Jours (in French). Paris: Éditions Vendémiaire. ISBN 978-2-36358-187-7.

- Souben, Monique (1989). La chouannerie dans le district de Redon : 1794-1799 (in French). Rue des Scribes édition. ISBN 978-2-906064-13-3.

- Tillet, Louise-Marie (1982). "Redon. Abbaye Saint-Sauveur". Bretagne romane. La Nuit des Temps (in French). Vol. 58. La Pierre-Qui-Vire: Saint-Léger-Vauban. pp. 73–79.

External links

[edit]- Religious resources: Clochers de France

- Resources on architecture: Mérimée

- Historique et description de l'abbaye de bénédictins Saint-Sauveur de Redon archive, Inventory of cultural heritage in Brittany