Saint-Jean-Baptiste de Montrésor Church

| Saint-Jean-Baptiste de Montrésor Church | |

|---|---|

Église Saint-Jean-Baptiste de Montrésor | |

Saint-Jean-Baptiste church. | |

| |

| Alternative names | Ancienne collégiale Saint-Jean-Baptiste |

| General information | |

| Type | Collegiate church |

| Town or city | Montrésor commune, Indre-et-Loire department, Centre-Val de Loire region. |

| Country | France |

| Coordinates | 47°09′20″N 01°12′13″E / 47.15556°N 1.20361°E |

| Construction started | 1522 |

| Construction stopped | ca. 1550 |

| Owner | Municipality of the Montrésor commune |

| Affiliation | John the Baptist |

| Awards and prizes | Monument historique (1840)[1] |

| Designations | Adscribed to the Roman Catholic Diocese of Séez jurisdiction from the Catholic Church confession |

The Saint-Jean-Baptiste de Montrésor Church is a former collegiate church located in the city of Montrésor, part of the Indre-et-Loire department in France.

Founded in 1521 by Imbert de Batarnay, Lord of Montrésor, as a family burial place and devoted to St. John the Baptist, it was immediately elevated to the rank of collegiate church, housing a chapter of five, then twelve, canons. Imbert de Batarnay died before construction was completed, but his body was finally interred some time later. From 1700, with the creation of the parish of Montrésor, it took on the function of parish church. At the time of the French Revolution, when the chapter of canons had been greatly reduced over the previous century, the last canons dispersed, but the church retained its parish function, which continues into the 21st century, despite being looted and seriously damaged in 1793.

The church has a rather original Lorraine cross plan. While its architecture reflects the late Gothic period, its interior and exterior decoration bear the imprint of the early French Renaissance. The church has undergone many restorations and repairs, notably in the second half of the 19th century, under the impetus of the Branicki family, and especially of Xavier Branicki, mayor of Montrésor from 1860 to 1870 and generous patron of the community. The restoration of the Batarnay tomb is one of the most symbolic interventions of this period, as is the interior decoration of the church, featuring paintings from the Italian Renaissance and classical schools.

The church is listed as a historic monument in 1840, and contains nineteen objects listed in the Palissy database of movable property protected by the French Ministry of Culture and Communication.

Location

[edit]

Located within the commune of Montrésor, some fifteen kilometers east of Loches, not far from the Indre-et-Loire - Indre border, the Saint-Jean-Baptiste de Montrésor church lies to the east of the château de Montrésor and to the northeast of the urban core it preceded, on the hillside of the right bank of a meander of the Indrois river; it is sustained by a terrace artificially leveled at an altitude of 100 m, ten meters above river level, slightly below the château (106 m). Breaking with the usual orientation of Christian religious buildings, its main portal faces north-west, and its apse points south-east.[2]

Until the 19th century, when it was filled in, an artificial moat dug into the plateau in medieval times protected the site on which the château and collegiate church stood to the north.[3] Two drawbridges, one of which was later replaced by a ramp and the other by a fixed bridge (Pont Bouvet), gave the squires direct access to the collegiate church by crossing the castle moat on what is now Rue Potocki.[4]

History

[edit]From the foundation to the seventeenth century

[edit]

Around 1520, Imbert de Batarnay, lord of Bridoré and Montrésor, had the idea of founding a collegiate church in which he and his family would be buried. His first choice was Bridoré, where he owned a medieval fortress,[5] and the project moved forward as early as March 1519.[6] However, in 1521, for unknown reasons, Imbert de Batarnay changed his mind and decided that the foundation would ultimately take place in Montrésor, not far from his Renaissance dwelling, as the 13th-century castral chapel was probably too cramped; construction began in March 1522.[7] Imbert de Batarnay endowed the collegiate church with "a college of five prebendal canons required to sing a daily high mass and canonical hours, with two young children instructed in reading and singing";[8] the number of canons was soon increased to twelve.[9] Imbert de Batarnay died in 1523. Since the church under construction was not yet suitable for his burial, he was buried in the château chapel before his body was relocated to the choir of the new collegiate church; the date of the transfer of his ashes is unknown.[10] The church was consecrated on December 10, 1532[11] by Archbishop Antoine de Bar, after completion of the structural work, but the work was not completed until 1541.[12] Work soon resumed, however, given that around 1550, at the instigation of René de Batarnay, Imbert's son, a chapel was built against the south side of the choir. It was dedicated to Notre-Dame-de-Lorette, in homage to the Basilica della Santa Casa, in the Italian province of Ancona, whose pilgrimages were renowned at the time.[13]

There seems to be no record of any damage caused to the newly built collegiate church during the Wars of Religion.

As early as 1680, the number of canons was reduced to four, in response to the collegiate church's low revenues;[14] at the same time, in 1683, Isabeau de Savoie, daughter-in-law of Imbert de Batarnay, extended the possibility of burial in the collegiate church to all inhabitants of Montrésor, "on condition that the income from such burial be used for repairs to the said church".[15] In 1700, the parish of Montrésor was created at the expense of Beaumont-Village, and the collegiate church of Saint-Jean-Baptiste became the parish place of worship.[16]

The eighteenth century and the French Revolution

[edit]Towards the mid-18th century, various works were carried out on the church, including two repairs to the bell tower and the removal of certain altars.[17]

In 1789, with the French Revolution, the chapter of canons was dissolved and the church was placed in the hands of the Nation in application of the decree of November 2, 1789. The events that took place in Montrésor during the revolutionary period are poorly documented,[18] but in 1793, the church suffered a great deal of damage: the Batarnay tomb was dismantled, but some of the fragments were left in situ,[19] the stained-glass windows were badly damaged and both the exterior and interior statues were destroyed or mutilated; two of the four bells disappeared.[20] The church resumed its parish function at the end of the French Revolution; from then on, the former Notre-Dame-de-Lorette chapel was used as the sacristy.[12]

From the Great Restoration of the 19th century to the present day

[edit]

The church was listed as a protected historic monument in 1840, but in 1853, the mayor of Montrésor wrote to the prefect expressing concern about the building's state of disrepair;[nb 1][21] in the same year, the Société archéologique de Touraine sent a commission to investigate the state of the Batarnay tomb, which had been demolished but with most of its more or less damaged parts stored in the church.[22] Major restoration work, largely financed by Count Branicki, took place in the second half of the 19th century. The bell tower, in poor condition, was dismantled in 1861; its reconstruction, temporarily interrupted in 1869, was completed in 1875. Architect Roguet oversaw the reconstruction, and a model of the new bell tower is on display at Château de Montrésor.[21] In 1867–69, the church was rebuilt with new roofing and roof timbers.[21] The Batarnay tomb was restored and reassembled in the north-west corner of the nave in 1875, at the same time as a previously walled-up window was opened at the end of the nave, above the portal, to illuminate the tomb.[23] The stained-glass window was rebuilt from elements of an earlier stained-glass window destroyed in 1793.[24] In 1877, worship returned to the Notre-Dame-de-Lorette chapel, while a small sacristy was built to the north of the choir. In 1883, the southern arm of the transept was restored and furnished from the abandoned Saint-Roch chapel, Montrésor's previous religious building;[25] the southern arm of the church's transept was renamed the "Saint-Roch chapel", while the chapel in the northern arm was consecrated to the Virgin.

The law of December 9, 1905 on the separation of Church and State confirmed the State's ownership of the church, which had been made available to it in 1789. In 1919, the portal was rebuilt; the central trumeau, in poor condition, was dismantled and stored inside the church.[26]

An agreement signed in 2013 between the municipality of Montrésor and the diocese of Tours enables cultural events to be held in the church.[27]

In 2015, Saint-Jean-Baptiste de Montrésor is one of eight places of worship in the parish of Montrésor, within the Archdiocese of Tours.[28][29]

Architecture

[edit]

The building, in its original layout prior to the construction of the Notre-Dame-de-Lorette chapel, is roughly in the shape of a Lorraine cross, its main branch being formed by the alignment of the choir and nave, the larger of the transverse branches being represented by the transept and the smaller by the chapels on the sides of the choir. The church is 34 m long, 8.70 m wide at nave level and 10 m high under vaulted ceiling.[21]

One of the few 16th-century[30] churches in Touraine to combine Gothic architecture with Renaissance decor, the church was much admired by Princess Dorothea of Courland, Duchesse de Dino, who described her visit to Montrésor on July 14, 1837, during a trip to Touraine and Berry with Talleyrand:

"[...] We then stopped at Montrésor, to inspect one of the finest Renaissance churches I have seen; it is built next to an old castle, which owes its origin to the famous Foulques Nera, the greatest builder before Louis-Philippe." - Duchesse de Dino, Chronique de 1831 à 1862.[31]

The façade and nave

[edit]

The façade, flanked by two angled buttresses, opens onto a portal formed by twin basket-handle doors separated by a trumeau, topped by a tympanum of five shell niches housing statues. A five-step staircase leads up to the portal. A skylight above the tympanum embellishes the nave.

The single nave, with no side aisles, comprises two bays with pointed arches. The location of the four stained-glass windows designed to illuminate the nave is simply marked, and the arches are blind.[32] A single door in the southern flank of the first bay provides further access to the nave via a six-step staircase.[3] A turret in the south-west corner of the building, whose staircase is accessible from the nave, leads to the attic.

Massive buttresses reinforce the façade at each corner, as well as the nave and choir between its two bays. While on the south side of the nave, the style is typical of the late Gothic period, with a double tier of pinnacles and volutes, on the north side, the Renaissance style is clearly applied, and they are decorated with coats of arms, many of which, damaged during the French Revolution, are difficult to identify; it is even possible to observe, at chevet level, "composite" buttresses comprising a single tier of volutes and pinnacles (Gothic) topped by a coat of arms (Renaissance).[33]

The transept and its chapels

[edit]

The transept consists of a single bay on either side of the nave, with buttresses at the outer corners. Its southern crossing is dedicated to Saint Roch.[34]

Two seigneurial chapels open into the last bay of the choir; they are linked to the corresponding transept arm by a corridor running parallel to the nave; this feature, known as the "passage berrichon", enabled the châtelains to reach their chapels without crossing the choir and without disrupting church services. These two chapels were initially covered with terraces, so as not to obstruct the view of the overhanging glass windows in the choir; it was only later that they were vaulted,[3] probably at the same time as the Notre-Dame-de-Lorette chapel was built.[35]

The Notre-Dame-de-Lorette chapel, used as a sacristy once worship had been re-established, measures 9 × 4 m and is buttressed[35] at the outer corners. It is accessed through a Renaissance door at the back of the south seigneurial chapel.

The choir

[edit]The choir has two bays, with side chapels opening into the second. It ends in a five-sided apse, supported by four plated buttresses. This apse was originally lit by five stained-glass windows (one per side), but the two outermost windows have been closed.[36] A slab on the floor in the center of the choir marks the site of the Batarnay family crypt, which, until the Revolution, was surmounted by the mausoleum. This crypt contained the bodies of Imbert de Batarnay and other members of his family, including Anne de Joyeuse.[37]

It is probable that a rood screen, which disappeared at an unknown date, ensured the "physical" separation between the transept and the choir.[34]

The vaults, roof and bell tower

[edit]

The cross and apse rib vaults are crossed by liernes and tiercerons; those in the choir aisle feature only half-ridges interrupted by medallions, suggesting the evolution of the decorative style; finally, those in the chapels are covered with semi-circular barrel vaults, several of which are decorated with bas-reliefs, and those in the side aisles with simple barrel vaults.[12] All keystones are decorated with the Batarnay coat of arms.[38]

The church has a slate roof, with two dormer windows added in the 19th century on each side to ensure attic ventilation.[21] A slate steeple on a wooden frame overhangs the transept crossing, while a hexagonal lantern ending in a dome, also covered in slate, sits atop the roof of the south transept crossing.

Decor and furnishings

[edit]Exterior decor

[edit]

A frieze runs along the upper part of the walls around the church. It is decorated with medallions bearing either historical heads or coats of arms; these motifs have been copied to decorate certain interior elements.[3]

Three empty niches with statues are located above the side door. These are topped by an engraved tympanum depicting scenes from the life of Jesus.[39] Three niches, empty of their statues, surmount the door.[40]

The tympanum surmounting the main portal features niches separated by colonnettes and housing statues, most of which were decapitated or mutilated during the French Revolution, but in which biblical figures (apostles, evangelists, etc.) are nonetheless recognizable.[41]

The sculptures and exterior decoration seem to have been executed between 1530, as the joint arms of René de Batarnay and Isabeau de Savoie are found in these decorations and 1530 is the probable date of their marriage, and 1541, as this date is mentioned in two inscriptions on the former trumeau of the main portal.[7][42]

The diversity of sculptural themes and their seemingly random distribution throughout the church's exterior decor suggests that there was no clearly defined plan for the decoration and that, on the contrary, the artists left much to their inspiration of the moment.[43]

The Batarnay family tomb

[edit]The Batarnay tomb,[44] located in the middle of the choir, was demolished in 1793, but numerous fragments were recovered and hidden in the vault above the monument. The entrance to this vault was fortuitously uncovered during work carried out during the Second Restoration, and the fragments of the tomb piled up in the chapels and transept.[45] A commission of members of the Société archéologique de Touraine visited the site in 1853 to assess the feasibility of restoring the tomb. Provisionally, the recumbent figures were replaced on a horizontal plank resting on a perpend stone, and the preserved statues were returned to their original position; however, this provisional restoration was opposed by the Historical Monuments Commission, and the whole structure was dismantled while the remains of the tomb were sheltered; another project, a little later, suffered the same fate.[22][45] It wasn't until 1875, at the instigation of Countess Branicka, that the tomb was restored by architect Roguet and sculptor Breuil,[45] as evidenced by an inscription on the monument.[40] However, instead of being placed in the middle of the choir as before, it was installed in the nave, to the left of the main portal, to facilitate the celebration of services. Moreover, in the absence of a description of the tomb in its original configuration, it is impossible to know whether it has been restored to its original state.[46]

The overall shape of the monument is square, measuring 2.3 m on each side and 1.05 m in height.[47] The base of the tomb is carved with niches underlined by colonnettes and arches. Before the French Revolution, these niches, set against a black marble background, housed alabaster statuettes representing the Twelve Apostles and the Four Evangelists; only twelve of these were able to be put back in place, after restoration following the mutilations of the Revolution (decapitation, in many cases), and four are missing;[48] the north side of the tomb, which faces the nave wall, is completely devoid of them.[49] Atop a thick slate slab lie three white marble recumbents: in the center, Georgette de Montchenu, who died and was buried in Blois in 1511,[50] whose feet rest on two griffins; to her right, her husband Imbert de Batarnay, who died in 1523, whose arms are supported by two lions; and to her left, their son François de Batarnay, who died in 1513 fighting in Picardy,[51] whose feet rest on a greyhound. Four kneeling angels bearing the coats of arms of the de Batarnay (Écartelé d'or et d'azur) and de Montchenu (De gueules à la bande engrêlée d'argent)[52] families adorn the four corners of the mausoleum.[53] The finesse and precision of the recumbent figures suggest that they may have been made from casts of the bodies.[54]

- Anne de Joyeuse, a descendant of the Batarnay family, and her brother Claude, killed at the battle of Coutras, are also buried in the collegiate church.

While the execution of the tombstones can be attributed to the workshop of Michel Colombe and his successors, such as Guillaume Regnault, or Martin Claustre,[34] the statues on the plinth are more likely the work of the Italian school.[48]

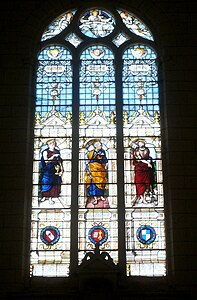

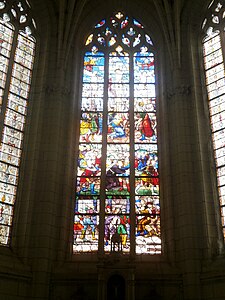

The stained-glass windows

[edit]When the church was built, eighteen openings were planned. Only four of these are fully open, one in the façade and three in the apse, while six others are only open at the top, the last eight having either never been opened or having been walled up at a later date,[55] perhaps for reasons of the building's solidity.[56] The choir's central window is decorated with a fine 16th-century stained-glass window depicting the Passion and Crucifixion,[57] so that the nave is lit by a single bay on the façade. The stained glass window above the entrance portal has been partially reconstructed from fragments of the church's original 16th-century choir window, destroyed in 1793;[58] it depicts St. Peter, St. John the Baptist and St. John the Evangelist.[43] The style of these windows can be attributed to the workshop of Touraine master glassmaker Robert Pinaigrier;[59] the restoration of the front window was the work of Eugène Oudinot.[24] The other windows are lined with white or simply decorated glass, which replaced the damaged stained-glass windows around 1842.[60]

The Notre-Dame-de-Lorette chapel (large sacristy) opens onto the exterior through an opening on its west side. This opening features a 15th-century stained-glass window,[61] probably from the former castral chapel destroyed in 1845.[62]

Indoor paintings and statues

[edit]

The north chapel features a 1636 painting of The Annunciation[nb 2][64] by Philippe de Champaigne,[65] donated by Count Branicki;[16] the painting was restored in 2002.[66] Cardinal Joseph Fesch, a great collector, amassed several thousand paintings. After his death, between 1841 and 1845, his collection was dispersed, and Xavier Branicki bought part of it. He donated four of these paintings, by the Italian school of the 16th century, to the church of Montrésor, where they now hang in the nave.[53] These four paintings, depicting scenes from the Passion of Christ: Ecce homo, Flagellation, Entombment and Resurrection, are attributable to Marcello Fogolino,[67] who may have been inspired for these works, as for others, by the paintings of Albrecht Dürer.[68][69]

Along the walls of the nave and choir, fourteen stone bas-reliefs represent the Way of the Cross.

The south cross houses a terracotta statue of Saint Roch, who can be identified by the dog accompanying him (during the Revolution, the animal was decapitated and Saint Roch lost an arm and a leg).[70] This statue comes from the Saint-Roch chapel in Montrésor; the chapel was abandoned during the Revolution, but the statue remained there until the 1980s, first inside, then in a niche outside the façade.[21] On the opposite wall of the transept crossing hangs a late 17th-century painting by an unknown artist, depicting Saint Blaise.[nb 3][72] In the sacristy, a 16th-century wooden statue of Notre-Dame de Lorette stands above an altar,[73] a reminder that this was once a chapel dedicated to this saint.[12] Between the large portal and the glass roof above, a niche houses a statue of Catherine of Alexandria.[74] Lastly, the choir houses an 11th-century statue of Christ in chased gilded bronze.[75]

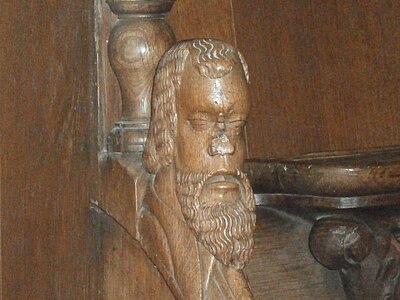

Other furnishings

[edit]The 16th-century stalls,[76] in which the chapter canons sat during services, are located on either side of the choir, on each side of the seigneurial chapels; they seat 21.[20] They are decorated with medallions, most of which feature motifs from the church's exterior frieze, and are fitted with mercy-seats enabling canons to lean on them during the standing part of services.[58]

Before the French Revolution, four bells were installed in the church tower. Two of these disappeared, having been recast in 1793. The largest of the two remaining bells, cast in 1599, weighs 635 kg;[77] the second, made in 1583, weighs 232 kg.[78]

In addition to the statue of Saint Roch, the south transept cross houses various items of furniture from the same chapel, such as an altar and an altarpiece.[34][79]

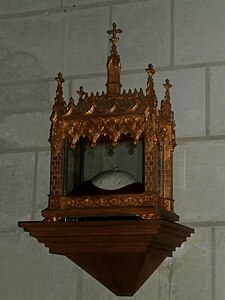

A rock-crystal altar cross, possibly from the Château de Versailles,[80] and a bust with a hollowed-out medallion for enshrining relics[81] are also among the objects protected as historic monuments.

One of the four zucchettos donated by Pope John Paul II during his pontificate was given to a seminarian from Montrésor. The latter's family made it available to the parish, which displays it in a shrine in the Montrésor church.[82]

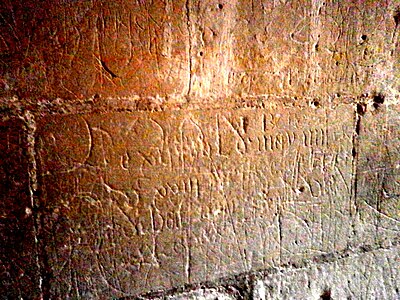

Mural inscriptions and graffiti

[edit]The walls of the corridors linking the transept crosspieces to the seigneurial chapels are almost entirely covered with graffiti engraved in stone, most of which are ex voto or simple tokens of a visitor's passage. Inscriptions on the walls of the transept crosses are rarer, and tend to relate significant events in the church's history. For example, it is mentioned that:

"LE 20 DE IVILLE [JUILLET] 16.60. [1660] LE. TONN RRE [TONNERRE]. TOMBA. SVR. LE CLOCHIER" (ON JULY 20TH, 1660, THE TONNERRE TOMB ON THE BELLTOWER)[83]

Notes

[edit]- ^ In this letter, the mayor mentions the incident that occurred at the start of a procession when an arch stone fell, fortunately without damage, on the priest's head.

- ^ A cat is depicted in a corner of the fireplace. The presence of this animal, which is not common in paintings dealing with this theme, adds an intimate dimension to the scene.[63]

- ^ Blaise is the patron saint of the wool carders' guild. This was an important activity in Montrésor until the 19th century.[71]

References

[edit]- ^ (fr)"Église paroissiale Saint-Jean-Baptiste, base Mérimée archive, notice no. PA00097877.

- ^ "Carte topographique du château de Montrésor archive" on Géoportail (accessed May 26, 2015).

- ^ a b c d (fr) Abbé Louis-Auguste Bossebœuf (pref. abbé Émile le Pironnec), De l'Indre à l'Indrois : Montrésor, le château, la collégiale, et ses environs : Beaulieu-Lès-Loches, Saint-Jean le Liget et la Corroirie, Res Universis, coll. "Monographie des villes et villages de France", 1897 (repr. 1993), 103 p. ISBN 2-7428-0097-2. p. 69.

- ^ (fr) Frédéric Gaultier and Michaël Beigneux, Montrésor se raconte, Montrésor, Association Montrésor se raconte, 2002, 169 p. ISBN 2-85443-411-0. p. 40.

- ^ (fr) "Château de Bridoré, base Mérimée" archive, notice no. PA00097602.

- ^ (fr) Abbé Louis-Auguste Bossebœuf (pref. abbé Émile le Pironnec), De l'Indre à l'Indrois : Montrésor, le château, la collégiale, et ses environs : Beaulieu-Lès-Loches, Saint-Jean le Liget et la Corroirie, Res Universis, coll. "Monographie des villes et villages de France", 1897 (repr. 1993), 103 p. ISBN 2-7428-0097-2. p. 59.

- ^ a b (fr) Jean Vallery-Radot, Actes du congrès archéologique de Tours, CVIe session (collective work), Tours, 1940, "L'ancienne collégiale de Montrésor", p. 195.

- ^ (fr) "Inventaire sommaire de la série G - clergé séculier (supplément)" archive [PDF], on the website of the archives of the Indre-et-Loire department, Indre-et-Loire Departmental Council, 2008 (accessed May 15, 2015), p. 11, call number G 1167.

- ^ (fr) Bernard Briais (ill. Denise Labouyrie), Vagabondages en Val d'Indrois, Monts, Séria, 2001, 127 p. (ISSN 1151-3012), p. 38.

- ^ (fr) Abbé Louis-Auguste Bossebœuf (pref. abbé Émile le Pironnec), De l'Indre à l'Indrois : Montrésor, le château, la collégiale, et ses environs : Beaulieu-Lès-Loches, Saint-Jean le Liget et la Corroirie, Res Universis, coll. "Monographie des villes et villages de France", 1897 (repr. 1993), 103 p. ISBN 2-7428-0097-2. p. 63.

- ^ (fr) Jacques-Xavier Carré de Busserolle, Dictionnaire géographique, historique et biographique d'Indre-et-Loire et de l'ancienne province de Touraine, t. IV, Société archéologique de Touraine, 1882, 430 p. (read online archive), p. 318.

- ^ a b c d (fr) Jean-Mary Couderc (dir.), Dictionnaire des communes de Touraine, Chambray-lès-Tours, C.L.D., 1987, 967 pp. ISBN 2-85443-136-7, p. 551.

- ^ (fr) Abbé Buchet, Le château et l'église collégiale de Montrésor, Tours, Paul Bouserez, 1876, p. 33.

- ^ (fr) Abbé Buchet, Le château et l'église collégiale de Montrésor, Tours, Paul Bouserez, 1876, p. 24.

- ^ (fr) "Inventaire sommaire de la série G - clergé séculier (supplément)" archive [PDF], 2008 (accessed July 20, 2015), p. 11, call number G 1167.

- ^ a b (fr) Bernard Briais (ill. Denise Labouyrie), Vagabondages en Val d'Indrois, Monts, Séria, 2001, 127 p. (ISSN 1151-3012), p. 33.

- ^ (fr) Jacques-Xavier Carré de Busserolle, Dictionnaire géographique, historique et biographique d'Indre-et-Loire et de l'ancienne province de Touraine, t. IV, Société archéologique de Touraine, 1882, 430 p. (read online archive), p. 319.

- ^ (fr) Frédéric Gaultier and Michaël Beigneux, Montrésor se raconte, Montrésor, Association Montrésor se raconte, 2002, 169 p. ISBN 2-85443-411-0. p. 64.

- ^ Vincent 1931, p. 35.

- ^ a b (fr) Abbé Buchet, Le château et l'église collégiale de Montrésor, Tours, Paul Bouserez, 1876, p. 34.

- ^ a b c d e f (fr) Frédéric Gaultier and Michaël Beigneux, Montrésor se raconte, Montrésor, Association Montrésor se raconte, 2002, 169 p. ISBN 2-85443-411-0. p. 60.

- ^ a b (fr) Charles Guyot, "Rapport sur le tombeau des Bastarnay à Montrésor", bulletin de la Société archéologique de Touraine, t. I, 1868-1870, p. 187-193 (read online archive).

- ^ (fr) Jean Vallery-Radot, Actes du congrès archéologique de Tours, CVIe session (collective work), Tours, 1940, "L'ancienne collégiale de Montrésor", p. 196.

- ^ a b (fr) Abbé Louis-Auguste Bossebœuf (pref. abbé Émile le Pironnec), De l'Indre à l'Indrois : Montrésor, le château, la collégiale, et ses environs : Beaulieu-Lès-Loches, Saint-Jean le Liget et la Corroirie, Res Universis, coll. "Monographie des villes et villages de France", 1897 (repr. 1993), 103 p. ISBN 2-7428-0097-2. p. 83.

- ^ (fr) Abbé Louis-Auguste Bossebœuf (pref. abbé Émile le Pironnec), De l'Indre à l'Indrois : Montrésor, le château, la collégiale, et ses environs : Beaulieu-Lès-Loches, Saint-Jean le Liget et la Corroirie, Res Universis, coll. "Monographie des villes et villages de France", 1897 (repr. 1993), 103 p. ISBN 2-7428-0097-2. p. 86.

- ^ (fr) Jean Vallery-Radot, Actes du congrès archéologique de Tours, CVIe session (collective work), Tours, 1940, "L'ancienne collégiale de Montrésor", p. 197-198.

- ^ (fr) "Une maison sociale à 161.000 E", La Nouvelle République du Centre-Ouest, January 24, 2013 (read online archive).

- ^ (fr) "La paroisse de Montrésor" archive, on the website of the Archdiocese of Tours (accessed May 1, 2015).

- ^ (fr) "Église Saint-Jean Baptiste de Montrésor" archive, on the Église-Info website of the Conférence des évêques de France (accessed May 1, 2015).

- ^ (fr) Bernard Briais, Le pays lochois et la Touraine côté sud : une terre de découvertes, Chambourg-sur-Indre, PBCO, 2010, 111 p. ISBN 978-2-35042-014-1, p. 21-22.

- ^ (fr) Duchesse de Dino, Chronique de 1831 à 1862, Paris, Plon, 1909-1910, 4 volumes, p. 165.

- ^ Ranjard 1930, p. 490.

- ^ (fr) Abbé Louis-Auguste Bossebœuf (pref. abbé Émile le Pironnec), De l'Indre à l'Indrois : Montrésor, le château, la collégiale, et ses environs : Beaulieu-Lès-Loches, Saint-Jean le Liget et la Corroirie, Res Universis, coll. "Monographie des villes et villages de France", 1897 (repr. 1993), 103 p. ISBN 2-7428-0097-2. p. 68.

- ^ a b c d (fr) Frédéric Gaultier, Montrésor, histoire d'un village, Montrésor, Le four banal, 2012, 19 p. ISBN 978-2-9543527-1-8, p. 11.

- ^ a b (fr) Abbé Louis-Auguste Bossebœuf (pref. abbé Émile le Pironnec), De l'Indre à l'Indrois : Montrésor, le château, la collégiale, et ses environs : Beaulieu-Lès-Loches, Saint-Jean le Liget et la Corroirie, Res Universis, coll. "Monographie des villes et villages de France", 1897 (repr. 1993), 103 p. ISBN 2-7428-0097-2. p. 84.

- ^ Ranjard 1930, p. 491.

- ^ (fr) Abbé Buchet, Le château et l'église collégiale de Montrésor, Tours, Paul Bouserez, 1876, p. 28.

- ^ (fr) Abbé Buchet, Le château et l'église collégiale de Montrésor, Tours, Paul Bouserez, 1876, p. 27.

- ^ (fr) Abbé Louis-Auguste Bossebœuf (pref. abbé Émile le Pironnec), De l'Indre à l'Indrois : Montrésor, le château, la collégiale, et ses environs : Beaulieu-Lès-Loches, Saint-Jean le Liget et la Corroirie, Res Universis, coll. "Monographie des villes et villages de France", 1897 (repr. 1993), 103 p. ISBN 2-7428-0097-2. p. 70.

- ^ a b (fr) Frédéric Gaultier and Michaël Beigneux, Montrésor se raconte, Montrésor, Association Montrésor se raconte, 2002, 169 p. ISBN 2-85443-411-0. p. 57.

- ^ (fr) Abbé Louis-Auguste Bossebœuf (pref. abbé Émile le Pironnec), De l'Indre à l'Indrois : Montrésor, le château, la collégiale, et ses environs : Beaulieu-Lès-Loches, Saint-Jean le Liget et la Corroirie, Res Universis, coll. "Monographie des villes et villages de France", 1897 (repr. 1993), 103 p. ISBN 2-7428-0097-2. p. 70-71.

- ^ (fr) Abbé Louis-Auguste Bossebœuf (pref. abbé Émile le Pironnec), De l'Indre à l'Indrois : Montrésor, le château, la collégiale, et ses environs : Beaulieu-Lès-Loches, Saint-Jean le Liget et la Corroirie, Res Universis, coll. "Monographie des villes et villages de France", 1897 (repr. 1993), 103 p. ISBN 2-7428-0097-2. p. 72.

- ^ a b (fr) Jean Vallery-Radot, Actes du congrès archéologique de Tours, CVIe session (collective work), Tours, 1940, "L'ancienne collégiale de Montrésor", p. 202.

- ^ "Tombeau de la famille Batarnay, base Palissy" archive, notice no PM37000678.

- ^ a b c (fr) Jean Vallery-Radot, Actes du congrès archéologique de Tours, CVIe session (collective work), Tours, 1940, "L'ancienne collégiale de Montrésor", p. 203.

- ^ (fr) Abbé Louis-Auguste Bossebœuf (pref. abbé Émile le Pironnec), De l'Indre à l'Indrois : Montrésor, le château, la collégiale, et ses environs : Beaulieu-Lès-Loches, Saint-Jean le Liget et la Corroirie, Res Universis, coll. "Monographie des villes et villages de France", 1897 (repr. 1993), 103 p. ISBN 2-7428-0097-2. p. 73.

- ^ (fr) Abbé Louis-Auguste Bossebœuf (pref. abbé Émile le Pironnec), De l'Indre à l'Indrois : Montrésor, le château, la collégiale, et ses environs : Beaulieu-Lès-Loches, Saint-Jean le Liget et la Corroirie, Res Universis, coll. "Monographie des villes et villages de France", 1897 (repr. 1993), 103 p. ISBN 2-7428-0097-2. p. 74.

- ^ a b (fr) Jean Vallery-Radot, Actes du congrès archéologique de Tours, CVIe session (collective work), Tours, 1940, "L'ancienne collégiale de Montrésor", p. 204.

- ^ (fr) Abbé Louis-Auguste Bossebœuf (pref. abbé Émile le Pironnec), De l'Indre à l'Indrois : Montrésor, le château, la collégiale, et ses environs : Beaulieu-Lès-Loches, Saint-Jean le Liget et la Corroirie, Res Universis, coll. "Monographie des villes et villages de France", 1897 (repr. 1993), 103 p. ISBN 2-7428-0097-2. p. 75.

- ^ (fr) Abbé Louis-Auguste Bossebœuf (pref. abbé Émile le Pironnec), De l'Indre à l'Indrois : Montrésor, le château, la collégiale, et ses environs : Beaulieu-Lès-Loches, Saint-Jean le Liget et la Corroirie, Res Universis, coll. "Monographie des villes et villages de France", 1897 (repr. 1993), 103 p. ISBN 2-7428-0097-2. p. 56.

- ^ (fr) Bernard de Mandrot, Ymbert de Batarnay, seigneur du Bouchage, conseiller des rois Louis XI, Charles VIII, Louis XII et François Ier (1438-1523), Paris, Alphonse Picard, 1886, 403 p., p. 242.

- ^ (fr) E. Jouffroy d'Eschavannes, Armorial universel, Paris, L. Curmer, 1844, 487 p., p. 44 and 277.

- ^ a b (fr) Frédéric Gaultier and Michaël Beigneux, Montrésor se raconte, Montrésor, Association Montrésor se raconte, 2002, 169 p. ISBN 2-85443-411-0. p. 58.

- ^ (fr) Bernard Briais (ill. Brigitte Champion), Découvrir la Touraine, la vallée de l'Indrois, Chambray-lès-Tours, CLD, 1979, 169 p., p. 98.

- ^ (fr) Frédéric Gaultier and Michaël Beigneux, Montrésor se raconte, Montrésor, Association Montrésor se raconte, 2002, 169 p. ISBN 2-85443-411-0. p. 56.

- ^ (fr) Abbé Louis-Auguste Bossebœuf (pref. abbé Émile le Pironnec), De l'Indre à l'Indrois : Montrésor, le château, la collégiale, et ses environs : Beaulieu-Lès-Loches, Saint-Jean le Liget et la Corroirie, Res Universis, coll. "Monographie des villes et villages de France", 1897 (repr. 1993), 103 p. ISBN 2-7428-0097-2. p. 81.

- ^ (fr) "Verrière du chœur, base Palissy" archive, notice no. PM37000637.

- ^ a b (fr) Bernard Briais (ill. Denise Labouyrie), Vagabondages en Val d'Indrois, Monts, Séria, 2001, 127 p. (ISSN 1151-3012), p. 40.

- ^ (fr) Abbé Louis-Auguste Bossebœuf (pref. abbé Émile le Pironnec), De l'Indre à l'Indrois : Montrésor, le château, la collégiale, et ses environs : Beaulieu-Lès-Loches, Saint-Jean le Liget et la Corroirie, Res Universis, coll. "Monographie des villes et villages de France", 1897 (repr. 1993), 103 p. ISBN 2-7428-0097-2. p. 82.

- ^ (fr) Abbé Buchet, Le château et l'église collégiale de Montrésor, Tours, Paul Bouserez, 1876, p. 29.

- ^ (fr) "Vitrail de la chapelle, base Palissy" archive, notice no. PM37001340.

- ^ (fr) Frédéric Gaultier and Michaël Beigneux, Montrésor se raconte, Montrésor, Association Montrésor se raconte, 2002, 169 p. ISBN 2-85443-411-0. p. 59.

- ^ Claire Stoullig, "Le temps des annonciations", Dossier de l'Art, December 2012, p. 24-27.

- ^ (fr) "Tableau de l'Annonciation, base Palissy" archive, notice no. PM37000314.

- ^ (fr) Sylvain Kespern, "Un décor d'église inconnu de Philippe de Champaigne?", Revue de l'Art, no. 118, 1997, p. 79 (DOI 10.3406/rvart.1997.348363).

- ^ (fr) "tableau 'L'Annonciation'" [archive], on the Ministry of Culture website (accessed August 6, 2015).

- ^ (fr) Frédéric Gaultier, Montrésor, histoire d'un village, Montrésor, Le four banal, 2012, 19 p. ISBN 978-2-9543527-1-8, p. 10.

- ^ (it) Marina Sennato, Larousse Dizionario della pittura italiana, Gremese Editore, 1998, 554 p. ISBN 88-7742-185-1, read online archive), p. 184.

- ^ (fr) "4 tableaux, base Aplissy" archive, notice no. PM37000313.

- ^ (fr) "Statue de Saint Roch, base Palissy" archive, notice no. PM37001338.

- ^ (fr) Bernard Briais (ill. Brigitte Champion), Découvrir la Touraine, la vallée de l'Indrois, Chambray-lès-Tours, CLD, 1979, 169 p., p. 81.

- ^ (fr) "Tableau de saint Blaise, base Palissy" archive, notice no. PM37001343.

- ^ (fr) "Statue de Notre-Dame de Lorette, base Palissy" archive, notice no. PM37000312.

- ^ (fr) "Statue de Catherine d'Alexandrie, base Palissy" archive, notice no. PM37001342.

- ^ (fr) "Statue du Christ, base Palissy" archive, notice no. PM37001341.

- ^ (fr) "Stalles, base Palissy" archive, notice no. PM37000310.

- ^ (fr) "Cloche, base Palissy" archive, notice no. PM37000315.

- ^ Vincent 1931, p. 36.

- ^ (fr) "Retable, base Palissy" archive, notice no. PM37000636.

- ^ (fr) "Croix, base Palissy" archive, notice no. PM37000316.

- ^ (fr) "Buste-reliquaire, base Palissy" archive, notice no. PM37000311.

- ^ (fr) Michel Marteau, "A Montrésor, la relique de Jean-Paul II est en place", La Nouvelle République du Centre-Ouest, April 21, 2015 (read online archive).

- ^ (fr) Jean-Mary Couderc, "Graffiti de Touraine, de France et d'ailleurs : une nouvelle source historique", mémoire de la Société archéologique de Touraine, t. LXXI, 2014, p. 38.

See also

[edit]Bibliography

[edit]- (fr) Abbé Louis-Auguste Bossebœuf (pref. abbé Émile le Pironnec), De l'Indre à l'Indrois : Montrésor, le château, la collégiale, et ses environs : Beaulieu-Lès-Loches, Saint-Jean le Liget et la Corroirie, Res Universis, coll. "Monographie des villes et villages de France", 1897 (repr. 1993), 103 p. ISBN 2-7428-0097-2

- (fr) Abbé Buchet, Le château et l'église collégiale de Montrésor, Tours, Paul Bouserez, 1876, 35 p.

- (fr) Frédéric Gaultier and Michaël Beigneux, Montrésor se raconte, Montrésor, Association Montrésor se raconte, 2002, 169 p. ISBN 2-85443-411-0.

- (fr) Jean Vallery-Radot, Actes du congrès archéologique de Tours, CVIe session (collective work), Tours, 1940, "L'ancienne collégiale de Montrésor", pp. 195–205.

- (fr) Robert Ranjard, La Touraine archéologique: guide du touriste en Indre-et-Loire, Mayenne, Imprimerie de la Manutention, 1930 (repr. 1986), 9th ed. 733 p. ISBN 2-85554-017-8.

- (fr) Émile Vincent, Montrésor: l'histoire, les environs, la collégiale, le château, Tours, Imprimerie du Progrès, 1931, 50 p.

Related articles

[edit]- Liste de collégiales de France

- Liste de miséricordes de France

- Liste des monuments historiques d'Indre-et-Loire (K-Z)

- List of French historic monuments protected in 1840