Chinese Century

The Chinese Century (simplified Chinese: 中国世纪; traditional Chinese: 中國世紀; pinyin: Zhōngguó shìjì) is a neologism suggesting that the 21st century may be geoeconomically or geopolitically dominated by the People's Republic of China,[1] similar to how the "American Century" refers to the 20th century and the "British Century" to the 19th.[2][3] The phrase is used particularly in association with the idea that the economy of China may overtake the economy of the United States to be the largest in the world.[4][5] A similar term is China's rise or rise of China (simplified Chinese: 中国崛起; traditional Chinese: 中國崛起; pinyin: Zhōngguó juéqǐ).[6][7]

China created the Belt and Road Initiative, which according to analysts has been a geostrategic effort to take a larger role in global affairs and challenges American postwar hegemony.[8][9][10] It has also been argued that China co-founded the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and New Development Bank to compete with the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund in development finance.[11][12] In 2015, China launched the Made in China 2025 strategic plan to further develop its manufacturing sector. There have been debates on the effectiveness and practicality of these programs in promoting China's global status.

China's emergence as a global economic power is tied to its large working population.[13] However, the population in China is aging faster than almost any other country in history.[13][14] Current demographic trends could hinder economic growth, create challenging social problems, and limit China's capabilities to act as a new global hegemon.[13][15][16][17] China's primarily debt-driven economic growth also creates concerns for substantial credit default risks and a potential financial crisis.

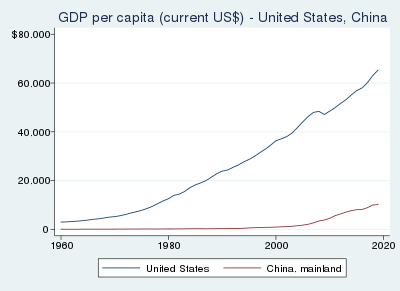

According to The Economist, on a purchasing-power-parity (PPP) basis, the Chinese economy became the world's largest in 2013.[18] On a foreign exchange rate basis, some estimates in 2020 and early 2021 said that China could overtake the U.S. in 2028,[19] or 2026 if the Chinese currency further strengthened.[20] As of July 2021, Bloomberg L.P. analysts estimated that China may either overtake the U.S. to become the world's biggest economy in the 2030s or never be able to reach such a goal.[21] Some scholars believe that China's rise has peaked and that an impending stagnation or decline may follow.[22][23][24]

Debates and factors

[edit]

China's economy was estimated to be the largest in the 16th, 17th and early 18th century.[25] Joseph Stiglitz said the "Chinese Century" had begun in 2014.[26] The Economist has argued that "the Chinese Century is well under way", citing China's GDP since 2013, if calculated on a purchasing-power-parity basis.[27]

From 2013, China created the Belt and Road Initiative, with future investments of almost $1 trillion[28] which according to analysts has been a geostrategic push for taking a larger role in global affairs.[8][9] It has also been argued that China co-founded the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and New Development Bank to compete with the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund in development finance.[11][12] In 2015, China launched the Made in China 2025 strategic plan to further develop the manufacturing sector, with the aim of upgrading the manufacturing capabilities of Chinese industries and growing from labor-intensive workshops into a more technology-intensive powerhouse.

In November 2020, China signed the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership as a free trade agreement[29][30][31] in counter to the Trans-Pacific Partnership.[32][33][34] The deal has been considered by some commentators as a "huge victory" for China,[35][36] although it has been shown that it would add just 0.08% to China's 2030 GDP without India's participation.[37][38]

Ryan Hass, a senior fellow in foreign policy at the Brookings Institution, said that much of the narrative of China "inexorably rising and on the verge of overtaking a faltering United States" was promoted by China's state-affiliated media outlets, adding, "Authoritarian systems excel at showcasing their strengths and concealing their weaknesses."[39] Political scientist Matthew Kroenig said, "the plans often cited as evidence of China's farsighted vision, the Belt and Road Initiative and Made in China 2025, were announced by Xi only in 2013 and 2015, respectively. Both are way too recent to be celebrated as brilliant examples of successful, long-term strategic planning."[40]

According to Barry Naughton, a professor and China expert at the University of California, San Diego, the average income in China was CN¥42,359 for urban households and CN¥16,021 for rural households in 2019. Even at the purchasing power parity conversion rate, the average urban income was just over US$10,000 and the average rural income was just under US$4,000 in China. Naughton questioned whether it is sensible for a middle income country of this kind to be taking "such a disproportionate part of the risky expenditure involved in pioneering new technologies". He commented that while it does not make sense from a purely economic perspective, Chinese policymakers have "other considerations" when implementing their industrial policy such as Made in China 2025.[41]

Depending on different assumptions of scenarios, it has been estimated that China would either overtake the U.S. to become the world's biggest economy in the 2030s or never be able to do so.[21]

International relations

[edit] |

| Top five countries by military expenditure in 2023.[42] |

In 2011, Michael Beckley, then a research fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School, released his journal China's Century? Why America's Edge Will Endure which rejects that the U.S. is in decline relative to China or that the hegemonic burdens the U.S. bears to sustain a globalized system contributes to its decline. Beckley argues the U.S. power is durable, and "unipolarity" and globalization are the main reasons. He says, "The United States derives competitive advantages from its preponderant position, and globalization allows it to exploit these advantages, attracting economic activity and manipulating the international system to its benefit."[43]

Beckley believes that if the United States was in terminal decline, it would adopt neomercantilist economic policies and disengage from military commitments in Asia. "If however, the United States is not in decline, and if globalization and hegemony are the main reasons why, then the United States should do the opposite: it should contain China’s growth by maintaining a liberal international economic policy, and it should subdue China’s ambitions by sustaining a robust political and military presence in Asia."[43] Beckley believes that the United States benefits from being an extant hegemon—the U.S. did not overturn the international order to its benefit in 1990, but rather, the existing order collapsed around it.

Scholars that are skeptical of the U.S.'s ability to maintain a leading position include Robert Pape, who has calculated that "one of the largest relative declines in modern history" stems from "the spread of technology to the rest of the world".[44] Similarly, Fareed Zakaria writes, "The unipolar order of the last two decades is waning not because of Iraq but because of the broader diffusion of power across the world."[45] Paul Kipchumba in Africa in China's 21st Century: In Search of a Strategy predicts a deadly cold war between the U.S. and China in the 21st century, and, if that cold war does not occur, he predicts China will supplant the U.S. in all aspects of global hegemony.[46]

Academic Rosemary Foot writes that the rise of China has led to some renegotiations of the U.S. hegemony in the Asia-Pacific region, but inconsistency between China's stated ambitions and policy actions has prompted various forms of resistance which leaves U.S. hegemony only partially challenged.[47] Meanwhile, C. Raja Mohan observes that "many of China’s neighbors are steadily drifting toward either neutrality between Beijing and Washington or simply acceptance of being dominated by their giant neighbor." However, he also notes that Australia, India, and Japan have readily challenged Beijing.[48] Richard Heyderian proposes that "America’s edge over China is its broad and surprisingly durable network of regional alliances, particularly with middle powers Japan, Australia and, increasingly, India, which share common, though not identical, concerns over China’s rising assertiveness."[49]

In the midst of global concerns that China's economic influence included political leverage, Chinese leader Xi Jinping stated "No matter how far China develops, it will never seek hegemony".[50] At several international summits, one being the World Economic Forum in January 2021, Chinese leader Xi Jinping stated a preference for multilateralism and international cooperation.[51] However, political scientist Stephen Walt contrasts the public message with China's intimidation of neighboring countries. Stephen Walt suggests that the U.S. "should take Xi up on his stated preference for multilateral engagement and use America’s vastly larger array of allies and partners to pursue favorable outcomes within various multilateral forums." Though encouraging the possibility of mutually beneficial cooperation, he argues that "competition between the two largest powers is to a considerable extent hardwired into the emerging structure of the international system."[51] According to former Singaporean Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, China will "[initially] want to share this century as co-equals with the U.S.", but have "the intention to be the greatest power in the world" eventually.[49]

Writing in the Asia Europe Journal, Lei Yu and Sophia Sui suggest that the China-Russia strategic partnership "shows China’s strategic intention of enhancing its 'hard' power in order to elevate its status at the systemic (global) level."[52]

In 2018, Xiangming Chen wrote that China was potentially creating a New Great Game, shifted to geoeconomic competition compared with the original Great Game. Chen stated that China would play the role of the British Empire (and Russia the role of the 19th century Russian Empire) in the analogy as the "dominant power players vs. the weaker independent Central Asian states". Additionally, he suggested that ultimately the Belt and Road Initiative could turn the "China-Central Asia nexus into a vassal relationship characterized by cross-border investment by China for border security and political stability."[53]

Rapid aging and demographic challenges

[edit]

China's emergence as a global economic power is tied to its large, working population.[13] However, the population in China is aging faster than almost any other country in history.[13][14] In 2050, the proportion of Chinese over retirement age will become 39 percent of the total population according to projections. China is rapidly aging at an earlier stage of its development than other countries.[13] Current demographic trends could hinder economic growth, create challenging social problems, and limit China's capabilities to act as a new global hegemony.[13][15][16][17]

Brendan O'Reilly, a guest expert at Geopolitical Intelligence Services, wrote, "A dark scenario of demographic decline sparking a negative feedback loop of economic crisis, political instability, emigration and further decreased fertility is very real for China".[54][55] Nicholas Eberstadt, an economist and demographic expert at the American Enterprise Institute, said that current demographic trends will overwhelm China's economy and geopolitics, making its rise much more uncertain. He said, "The age of heroic economic growth is over."[56]

Ryan Hass at the Brookings said that China's "working-age population is already shrinking; by 2050, China will go from having eight workers per retiree now to two workers per retiree. Moreover, it has already squeezed out most of the large productivity gains that come with a population becoming more educated and urban and adopting technologies to make manufacturing more efficient."[39]

According to American economist Scott Rozelle and researcher Natalie Hell, "China looks a lot more like 1980s Mexico or Turkey than 1980s Taiwan or South Korea. No country has ever made it to high-income status with high school attainment rates below 50 percent. With China's high school attainment rate of 30 percent, the country could be in grave trouble." They warn that China risks falling into the middle income trap due to the rural urban divide in education and structural unemployment.[57][58] Economists Martin Chorzempa and Tianlei Huang of the Peterson Institute agree with this assessment, adding that "China has overlooked rural development much too long", and must invest in the educational and health resources of its rural communities to solve an ongoing human capital crisis.[58]

Economic growth and debt

[edit]

The People's Republic of China was the only major economy that reported growth in 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic.[59] The economy of China expanded by 2.3% while the U.S. economy and the eurozone are expected to have shrunk by 3.6% and 7.4% respectively. China's share of the global GDP rose to 16.8%, while the U.S. economy accounted for 22.2% of global GDP in 2020.[60] By the end of 2024, however, the Chinese economy is expected to be smaller than what was previously projected, while the U.S. economy is expected to be larger, according to the International Monetary Fund's 2021 report on the global economic outlook.[61]

China's increased lending has been primarily driven by its desire to increase economic growth as fast as possible. The performance of local government officials has for decades been evaluated almost entirely on their ability to produce economic growth. Amanda Lee reports in the South China Morning Post that "as China’s growth has slowed, there are growing concerns that many of these debts are at risk of default, which could trigger a systemic crisis in China’s state-dominated financial system".[62]

Diana Choyleva of Enodo Economics predicts that China's debt ratio will soon surpass that of Japan at the peak of its crisis.[63] Choyleva argues "For evidence that Beijing realizes it is drowning in debt and needs a lifebuoy, look no further than the government's own actions. It is finally injecting a degree of pricing discipline into the corporate bond market and it is actively encouraging foreign investors to help finance the reduction of a huge pile of bad debt."[63]

China's debt-to-GDP ratio increased from 178% in the first quarter of 2010 to 275% in the first quarter of 2020.[63] China's debt-to-GDP ratio approached 335% in the second and third quarters of 2020.[62] Ryan Hass at the Brookings said, "China is running out of productive places to invest in infrastructure, and rising debt levels will further complicate its growth path."[39]

The PRC government regularly revises its GDP figures, often toward the end of the year. Because local governments face political pressure to meet pre-set growth targets, many doubt the accuracy of the statistics.[64] According to Chang-Tai Hsieh, an economist at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business and research associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research, Michael Zheng Song, an economics professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, and coauthors, China's economic growth may have been overstated by 1.7 percent each year between 2008 and 2016, meaning that the government may have been overstating the size of the Chinese economy by 12-16 percent in 2016.[65][66]

According to American strategist and historian Edward Luttwak, China will not be burdened by huge economic or population problems, but will fail strategically because "the emperor makes all the decisions and he doesn't have anybody to correct him." He said that geopolitically, China "gained one year in the race" in 2020 by using the measures of a totalitarian government, but this has brought the "China threat" to the fore, pushing other governments to respond.[67]

Sociologist Ho-Fung Hung stated that, although China's extensive lending during the COVID-19 pandemic allowed a quick rebound after the initial lockdown, it contributed to the already deep indebtedness of many of China's corporations, slowing the economy by 2021 and depressing long-term performance. Hung also pointed out that in 2008, although it was claimed mainly in propaganda that the Chinese yuan could overtake the US dollar as a reserve currency, after a decade the yuan has since stalled and decreased in international usage, ranking below the British pound sterling, let alone the dollar.[68]

Chinese decline

[edit]Some scholars argue that China's rise will be over by the 2020s. According to foreign policy experts Michael Beckley and Hal Brands, China, as a revisionist power, has little time to change the status quo of the world in its favor due to "severe resource scarcity", "demographic collapse", and "losing access to the welcoming world that enabled its advance", adding that "peak China" has already come.[22]

According to Andrew Erickson of the U.S. Naval War College and Gabriel Collins of the Baker Institute, China's power is peaking, creating "a decade of danger from a system that increasingly realizes it only has a short time to fulfill some of its most critical, long-held goals".[23] David Von Drehle, a columnist for The Washington Post, wrote that it would be more difficult for the West to manage China's decline than its rise.[69]

According to John Mueller at the Cato Institute, a "descent or at least prolonged stagnation might come about, rather than a continued rise" for China. He listed the environment, corruption, ethnic and religious tensions, Chinese hostility toward foreign businesses, among others, as contributing factors to China's impending decline.[24]

According to Yi Fuxian, a demography and health researcher at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, the Chinese Century is "already over".[70]

See also

[edit]- China specific

- Adoption of Chinese literary culture

- Belt and Road Initiative

- Century of humiliation

- Chinese Dream

- Chinese economic reform

- China's peaceful rise

- China Lobby

- Economy of China

- List of disputed territories of China

- Pax Sinica

- String of Pearls (Indian Ocean)

- Counter China

- Blue Team (U.S. politics)

- China containment policy

- Quadrilateral Security Dialogue

- Geostrategy in Central Asia

- Malabar (naval exercise)

- China–United States relations

- India–United States relations

- Japan–United States relations

- General

References

[edit]- ^ Brands, Hal (February 19, 2018). "The Chinese Century?". The National Interest. Archived from the original on March 14, 2021. Retrieved March 18, 2021.

- ^ Rees-Mogg, William (3 January 2005). "This is the Chinese century". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 12 April 2020. Retrieved 12 September 2009.

- ^ admin (2014-06-04). "Empires and Colonialism in the 19th Century". American Numismatic Society. Retrieved 2024-10-21.

- ^ "Global Economy Watch - Projections > Real GDP / Inflation > Share of 2016 world GDP". PWC. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- ^ Thurow, Lester (August 19, 2007). "A Chinese Century? Maybe It's the Next One (Published 2007)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 9, 2020. Retrieved March 18, 2021.

- ^ Freeman, Charles; Bergsten, C. Fred; Lardy, Nicholas R.; Mitchell, and Derek J. (23 September 2008). "China's Rise". www.csis.org. Archived from the original on 2020-12-23. Retrieved 2021-03-17.

- ^ Han, Zhen; Paul, T. V. (2020-03-01). "China's Rise and Balance of Power Politics". The Chinese Journal of International Politics. 13 (1): 1–26. doi:10.1093/cjip/poz018. Archived from the original on 2020-05-08. Retrieved 2021-03-17.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "China's one belt, one road initiative set to transform economy by connecting with trading partners along ancient Silk Road". South China Morning Post. 21 June 2016. Archived from the original on 7 January 2017. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "One Belt, One Road". Caixin Online. 2014-12-10. Archived from the original on 2016-09-12. Retrieved 2016-04-13.

- ^ "What Does China's Belt and Road Initiative Mean for US Grand Strategy?". thediplomat.com. Retrieved 2021-07-24.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "AIIB Vs. NDB: Can New Players Change the Rules of Development Financing?". Caixin. Archived from the original on 2016-12-26. Retrieved 26 December 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Cohn, Theodore H. (2016-05-05). Global Political Economy: Theory and Practice. Routledge. ISBN 9781317334811.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g "Does China have an aging problem?". ChinaPower Project. Feb 15, 2016. Archived from the original on 2019-05-18. Retrieved 2019-05-16.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kapadia, Reshma (September 7, 2019). "What Americans Can Learn From the Rest of the World About Retirement". Barron's. Archived from the original on March 16, 2021. Retrieved February 3, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Tozzo, Brandon (October 18, 2017). "The Demographic and Economic Problems of China". American Hegemony after the Great Recession. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 79–92. doi:10.1057/978-1-137-57539-5_5. ISBN 978-1-137-57538-8.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Eberstadt, Nicholas (June 11, 2019). "With Great Demographics Comes Great Power". Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on January 20, 2021. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sasse, Ben (January 26, 2020). "The Responsibility to Counter China's Ambitions Falls to Us". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 8 February 2021. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- ^ "The Chinese century is well under way". The Economist. 2018-10-27. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 2021-07-24.

- ^ Elliot, Larry (26 December 2020). "China to overtake US as world's biggest economy by 2028, report predicts". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

With the US expected to contract by 5% this year, China will narrow the gap with its biggest rival, the CEBR said. Overall, global gross domestic product is forecast to decline by 4.4% this year, in the biggest one-year fall since the second world war. Douglas McWilliams, the CEBR's deputy chairman, said: "The big news in this forecast is the speed of growth of the Chinese economy. We expect it to become an upper-income economy during the current five-year plan period (2020-25). And we expect it to overtake the US a full five years earlier than we did a year ago. It would pass the per capita threshold of $12,536 (£9,215) to become a high-income country by 2023.

- ^ Cheng, Evelyn; Lee, Yen Nee (February 2021). "New chart shows China could overtake the U.S. as the world's largest economy earlier than expected". CNBC. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

could

- ^ Jump up to: a b Zhu, Eric; Orlik, Tom (11 February 2022). "When Will China Rule the World? Maybe Never". Bloomberg News. Bloomberg News. Retrieved 8 August 2022.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Beckley, Michael; Brands, Hal (2021-12-09). "The End of China's Rise". Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 2022-01-18.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Erickson, Andrew S.; Collins, Gabriel B. "A Dangerous Decade of Chinese Power Is Here". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- ^ Jump up to: a b John Mueller (21 May 2021). "China: Rise or Demise?". Cato Institute. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- ^ Holodny, Elena. "The rise, fall, and comeback of the Chinese economy over the past 800 years". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 2021-02-27. Retrieved 2021-03-06.

- ^ Stiglitz, Joseph E. (4 December 2014). "China Has Overtaken the U.S. as the World's Largest Economy". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on 2020-12-05. Retrieved 2021-03-06.

- ^ "The Chinese century is well under way". The Economist. 2018-10-27. ISSN 0013-0613. Archived from the original on 2021-02-12. Retrieved 2021-01-28.

- ^ "China is spending nearly $1 trillion to rebuild the Silk Road". PBS. 2 March 2016. Archived from the original on 6 January 2017. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- ^ "RCEP: China, ASEAN to sign world's biggest trade pact today, leave door open for India". Business Today. 15 November 2020. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- ^ "RCEP: Asia-Pacific countries form world's largest trading bloc". BBC News. 15 November 2020. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- ^ "China signs huge Asia Pacific trade deal with 14 countries". CNN. 16 November 2020. Archived from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- ^ "China Touts Its Own Trade Pact as U.S.-Backed One Withers". The Wall Street Journal. 22 November 2016. Archived from the original on 31 January 2017. Retrieved 2 February 2017.

- ^ Harding, Robin (10 November 2016). "Beijing plans rival Asia-Pacific trade deal after Trump victory". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 14 January 2017. Retrieved 2 February 2017.

- ^ "China Eager to Fill Political Vacuum Created by Trump's TPP Withdrawal". Bloomberg.com. Bloomberg News. 23 January 2017. Archived from the original on 2017-02-02. Retrieved 2 February 2017.

- ^ "World's biggest trade deal signed – and doesn't include US". South China Morning Post. 2020-11-15. Archived from the original on 2020-11-15. Retrieved 2020-12-01.

- ^ "RCEP, a huge victory in rough times". Archived from the original on 2021-02-08. Retrieved 2021-02-03.

- ^ Bird, Mike (November 5, 2019). "Asia's Huge Trade Pact Is a Paper Tiger in the Making". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on December 7, 2020. Retrieved February 1, 2021.

- ^ Mahadevan, Renuka; Nugroho, Anda (September 10, 2019). "Can the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership minimise the harm from the United States–China trade war?". The World Economy. 42 (11). Wiley: 3148–3167. doi:10.1111/twec.12851. ISSN 0378-5920. S2CID 202308592.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Hass, Ryan (March 3, 2021). "China Is Not Ten Feet Tall". Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on March 4, 2021. Retrieved March 4, 2021.

- ^ Kroenig, Matthew (April 3, 2020). "Why the U.S. Will Outcompete China". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on December 19, 2020. Retrieved March 5, 2021.

- ^ Barry Naughton. "The Rise of China's Industrial Policy, 1978 to 2020". Lynne Rienner Publishers. Retrieved March 18, 2021.

- ^ "Trends in World Military Expenditure, 2023" (PDF). Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. April 2024. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 October 2024. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Beckley, Michael (Winter 2011–2012). "China's Century? Why America's Edge Will Endure" (PDF). International Security. 36 (3): 41–78, p. 42. doi:10.1162/isec_a_00066. S2CID 57567205. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 September 2012. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- ^ Pape, Robert (January–February 2009). "Empire Falls". The National Interest: 26. Archived from the original on 7 November 2012. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- ^ Zakaria, Fareed (2009). The Post-American World. New York: W. W. Norton. p. 43. ISBN 9780393334807.

- ^ Kipchumba, Paul, Africa in China's 21st Century: In Search of a Strategy, Nairobi: Kipchumba Foundation, 2017, ISBN 197345680X ISBN 978-1973456803

- ^ Foot, Rosemary (2020-04-01). "China's rise and US hegemony: Renegotiating hegemonic order in East Asia?". International Politics. 57 (2): 150–165. doi:10.1057/s41311-019-00189-5. ISSN 1740-3898. S2CID 203083774. Archived from the original on 2021-03-27. Retrieved 2021-03-06.

- ^ Mohan, C. Raja. "A New Pivot to Asia". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 2021-03-05. Retrieved 2021-03-06.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Heydarian, Richard Javad (2019-12-08). "Will the Chinese Century End Quicker Than It Began?". The National Interest. Archived from the original on 2021-01-25. Retrieved 2021-03-06.

- ^ "China will 'never seek hegemony,' Xi says in reform speech". AP NEWS. 2018-12-18. Archived from the original on 2020-12-15. Retrieved 2021-03-06.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Walt, Stephen M. "Xi Tells the World What He Really Wants". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 2021-02-19. Retrieved 2021-03-06.

- ^ Yu, Lei; Sui, Sophia (2020-09-01). "China-Russia military cooperation in the context of Sino-Russian strategic partnership". Asia Europe Journal. 18 (3): 325–345. doi:10.1007/s10308-019-00559-x. ISSN 1612-1031. S2CID 198767201. Archived from the original on 2021-03-27. Retrieved 2021-03-06.

- ^ Chen, Xiangming; Fazilov, Fakhmiddin (2018-06-19). "Re-centering Central Asia: China's "New Great Game" in the old Eurasian Heartland". Palgrave Communications. 4 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1057/s41599-018-0125-5. ISSN 2055-1045. S2CID 49311952.

- ^ "Changes in the structure of populations are major drivers of geopolitical events". Geopolitical Intelligence Services. December 20, 2017. Archived from the original on January 24, 2021. Retrieved February 3, 2021.

- ^ O'Reilly, Brendan (September 21, 2016). "China has few resources to prepare its economy for the impact of an aging and shrinking population". Geopolitical Intelligence Services. Archived from the original on October 1, 2020. Retrieved February 3, 2021.

- ^ LeVine, Steve (July 3, 2019). "Demographics may decide the U.S-China rivalry". Axios. Archived from the original on July 20, 2020. Retrieved February 16, 2021.

- ^ Hell, Natalie, and Rozelle, Scott. Invisible China: How the Urban-Rural Divide Threatens China’s Rise. University of Chicago Press, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Huang, Martin Chorzempa, Tianlei. "China Will Run Out of Growth if It Doesn't Fix Its Rural Crisis". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 2021-03-16. Retrieved 2021-03-17.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cherney, Stella Yifan Xie, Eun-Young Jeong and Mike (2021-01-13). "China's Economy Powers Ahead While the Rest of the World Reels". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 2021-03-09. Retrieved 2021-03-06.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Albert, Eleanor. "China's Xi Champions Multilateralism at Davos, Again". thediplomat.com. Archived from the original on 2021-02-20. Retrieved 2021-03-06.

- ^ "World Economic Outlook, April 2021: Managing Divergent Recoveries". International Monetary Fund. 23 March 2021. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

Figure 1.16. Medium-Term GDP Losses Relative to Pre-COVID-19, by Region

- ^ Jump up to: a b "How big is China's debt, who owns it and what is next?". South China Morning Post. 2020-05-19. Archived from the original on 2021-02-04. Retrieved 2021-02-06.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "China's local government debts should be the real worry". Nikkei Asia. Archived from the original on 2021-02-05. Retrieved 2021-02-06.

- ^ Cheng, Evelyn (2020-12-30). "China revises 2019 GDP lower with a $77 billion cut to manufacturing". CNBC. Archived from the original on 2021-02-14. Retrieved 2021-02-06.

- ^ Wildau, Gabriel (2019-03-07). "China's economy is 12% smaller than official data say, study finds". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 20 July 2019. Retrieved 20 July 2019.

- ^ "China's economy might be nearly a seventh smaller than reported". The Economist. 7 March 2019. ISSN 0013-0613. Archived from the original on 20 July 2019. Retrieved 20 July 2019.

- ^ "Edward Luttwak Predicts that 'Technological Acceleration' Will Drive Forward 2021". JAPAN Forward. December 31, 2020. Archived from the original on February 19, 2021. Retrieved March 26, 2021.

- ^ "It's Too Soon to Announce the Dawn of a Chinese Century". jacobinmag.com. Retrieved 2022-05-09.

- ^ "Opinion | What if, instead of confronting China's rise, we must manage its decline?". Washington Post. Retrieved 18 January 2022.

- ^ Yi, Fuxian (10 March 2023). "The Chinese century is already over". The Japan Times. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

Further reading

[edit]- Global Trends 2025: A Transformed World. Cosimo. March 2010. p. 7. ISBN 9781605207711.

- Brown, Kerry (2017) China's World: The Global Aspiration of the Next Superpower. I. B. Tauris, Limited ISBN 9781784538095.

- Brahm, Laurence J. (2001) China's Century: The Awakening of the Next Economic Powerhouse. Wiley ISBN 9780471479017.

- Fishman, Ted (2006) China, Inc.: How the Rise of the Next Superpower Challenges America and the World. Scribner ISBN 9780743257350.

- Jacques, Martin (2012) When China Rules the World: The End of the Western World and the Birth of a New Global Order. Penguin Books ISBN 9780143118008.

- Hung, Ho-fung (2015). The China Boom: Why China Will Not Rule the World. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-54022-3.

- Overholt, William (1994) The Rise of China: How Economic Reform is Creating a New Superpower. W. W. Norton & Company ISBN 9780393312454.

- Peerenboom, Randall (2008) China Modernizes: Threat to the West or Model for the Rest?. Oxford University Press ISBN 9780199226122.

- Pillsbury, Michael (2016) The Hundred-Year Marathon: China's Secret Strategy to Replace America as the Global Superpower. St. Martin's Griffin ISBN 9781250081346.

- Schell, Orville (2014) Wealth and Power: China's Long March to the Twenty-first Century. Random House Trade Paperbacks ISBN 9780812976250.

- Shenkar, Oded (2004) The Chinese Century: The Rising Chinese Economy and Its Impact on the Global Economy, the Balance of Power, and Your Job. FT Press ISBN 9780131467484.

- Shambaugh, David (2014) China Goes Global: The Partial Power. Oxford University Press ISBN 9780199361038.

- Womack, Brantly (2010) China's Rise in Historical Perspective. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers ISBN 9780742567221.

- Yueh, Linda (2013) China's Growth: The Making of an Economic Superpower. Oxford University Press ISBN 9780199205783.

- Dahlman, Carl J; Aubert, Jean-Eric. (2001) China and the Knowledge Economy: Seizing the 21st Century. WBI Development Studies. World Bank Publications.

- Hell, Natalie; Rozelle, Scott. (2020) Invisible China: How the Urban-Rural Divide Threatens China’s Rise. University of Chicago Press ISBN 9780226739526.