Red Turban Rebellions

| Late Yuan rebellions | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

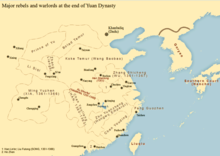

Distribution of major rebel forces and Yuan warlords | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| Belligerents | ||||||||||

|

Principality of Liang (Yunnan) (1372– Goryeo (1270– |

Northern Red Turban rebels: Western Wu (1361– Ming dynasty (from 1368) |

Southern Red Turban rebels: Chen Han dynasty (1360– Ming Xia dynasty (1361– |

Zhou (1354– Wu (1363– |

Other southern warlords Fujian Muslim rebels (1357– Northern warlords | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

Zhang Shicheng

|

| ||||||

| Strength | ||||||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | ||||||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

The Red Turban Rebellions (Chinese: 紅巾起義; pinyin: Hóngjīn Qǐyì) were uprisings against the Yuan dynasty between 1351 and 1368, eventually leading to its collapse. Remnants of the Yuan imperial court retreated northwards and is thereafter known as the Northern Yuan in historiography.

Background

[edit]Factional strife

[edit]In the early 1300s, the imperial court of the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty was split between two factions on how best to govern the empire. One faction favored a Mongol-centric policy that favored Mongol and Inner Asian interests while the opposing faction leaned towards a more Han-based "Confucian" governing style. The latter group conducted a coup in 1328 to enthrone Kusala (Emperor Mingzong). Kusala was literate in the Chinese language and made efforts to write Chinese poetry and to produce Chinese calligraphy. He patronized Chinese learning and art with a new academy and office in the inner court. Others at court such as the Merkit Majarday and his son, Toqto'a, also led the way in cultivating Chinese learning by establishing contacts with ethnic Han scholars and hiring them as tutors.[1] Kusala was assassinated by supporters of his half-brother, Tugh Temür (Emperor Wenzong). Tugh Temür died in 1332 and was succeeded by Kusala’s six-year-old child, Rinchinbal (Emperor Ningzong), who died six months later. His older brother, Toghon Temür (Emperor Huizong), became emperor at the age of 13. He was the last emperor of the Yuan dynasty.[2]

Military decline

[edit]

By the time Kublai (Emperor Shizu) conquered the Central Plain, the Yuan army was composed mostly of professional Han soldiers who had once been subject to the Jin dynasty prior to its conquest by the Mongols. These soldiers, sometimes under Mongol or Inner Asian command, were garrisoned across the empire and served as the primary body of the Yuan army. Some special Mongol units were dispatched to strategic locations as needed, but not to police the empire and not on a regular basis. Most of the Mongol garrisons were located to the north around the capital of Khanbaliq. Yuan garrisons had already entered a steep decline by the end of the 13th century and by 1340, repeatedly failed to put down local rebellions.[3] In the 1340s a bandit gang of merely 36 persons in Huashan took over a Daoist temple. For more than three months, government forces from three provinces failed to defeat them. It was only when salt-field workers, noted for their fierceness and independence in Hangzhou, were brought in to handle the situation that the bandits were defeated. From that time on the people of the realm regarded the government forces as useless and depended on local leadership for defense, contributing to the process of decentralization.[4] At the same time the Yuan also had to contend with rebellious Jurchens, who revolted in 1343. The Jurchens resented the Mongols for having to supply them with gyrfalcons. Efforts to suppress the Jurchen rebellion failed and by 1348, at least two Jurchen groups no longer obeyed Yuan authority. Their leaders claimed to be descendants of the Jin dynasty.[5]

Natural disasters

[edit]Since the 1340s, the Yuan dynasty had experienced problems. The Yellow River flooded constantly and other natural disasters also occurred. At the same time the Yuan dynasty required considerable military expenditure to maintain its vast empire.[6] Groups or religious sects made an effort to undermine the power of the last Yuan rulers; these religious movements often warned of impending doom. Decline of agriculture, epidemics and cold weather hit China, spurring the armed rebellion.[7] The earliest record of an unusual epidemic during the 14th century says that in the year 1331, an epidemic occurred in Hebei and then spread elsewhere, killing 13 million people by 1333. Another epidemic ravaged Fujian and Shandong from 1344 to 1346. The epidemic returned in Shanxi, Hebei, and Jiangsu in 1351–52. Additional epidemics were recorded in various provinces from 1356 to 1360 and "great pestilences" every year from 1356 to 1362. In Shanxi and Hebei, 200,000 people died in 1358.[8]

The rebellions themselves were the final stage of a long history of Chinese resentment against Mongol rule, expressed at the elite level by reluctance to serve in the government and at the popular level by clandestine sectarian activity. The occasion for the rebellions was the failure of the Yuan regime to cope with widespread famine in the 1340s. By the time those occurred, paradoxically the Yuan ruling elite had largely come to an accommodation with the native Chinese political tradition.[9]

— Frederick W. Mote

Red Turbans

[edit]The Red Turbans first appeared in Jiangxi and Hunan in the 1330s. From there they spread throughout half of China within a dozen years, moving clandestinely into provinces affected by natural disasters. Their religious teachings created sects with broad local followings that practiced night gatherings of men and women to burn incense and worship Mile Pusa. Eventually these sects coalesced into two broad movements: the southern (or western) Red Turbans in southern Hubei and the northern (or eastern) Red Turbans based in the Huai River region in Anhui.[10]

The Red Turban movement traces its origins to Peng Yingyu, a Buddhist monk, who led an uprising in Yuanzhou (in modern Jiangxi) in 1338. A rebel leader, Zhou Ziwang, was proclaimed emperor, but he was quickly apprehended by regional authorities and executed. Peng fled northwards and spread the teaching of the coming of the Maitreya, the Buddha of wealth and radiance, who would bring an end to suffering. Red Turban influence appeared in many places along the Huai River from 1340 onward.[11]

Rebellions

[edit]

Northern Red Turbans

[edit]In 1351, a mass mobilization of workers from the farming population, numbering 150,000 in total, for a project to rechannel the Yellow River and to open the Grand Canal in western Shandong saw ripe conditions for recruitment by the Red Turbans. A Red Turban leader, Han Shantong, and his advisor, Liu Futong, successfully recruited from the disgruntled workers, resulting in explosive rebellious activity. Han Shantong was captured and executed, but his wife and son, Han Lin'er, escaped with Liu. Liu established a capital at Yingzhou in modern western Anhui at the Hunan border and proclaimed the establishment of a Red Turban government. Han Lin'er was proclaimed the "Young Prince of Radiance" hailing from Song dynasty royalty.[12]

Han Lin'er was proclaimed emperor of a restored Song dynasty in Bozhou (in western Anhui) on 16 March 1355. On 11 June 1358, Liu Futong set out to capture Kaifeng, which had been the capital of the Song dynasty. The city was only held briefly by the new Song dynasty before a counteroffensive by Chaghan Temur forced them to retreat on 10 September 1359. Han Lin'er's court fled to Anfeng where they remained until Zhang Shicheng sent an army against them in 1363.[13]

In the northeast, the Red Turbans invaded Goryeo in 1359 and 1360. It is uncertain what exactly caused the Red Turbans to attack Goryeo but it was most likely due to material considerations. The Red Turbans in Liaodong had proven inferior to the soldiers of Chaghan Temur, who had defeated them in battle, and possibly saw Goryeo as an easier target unprotected by Mongol forces. The Red Turbans were also facing starvation and needed grain and supplies. There may have also been ethnic and political reasons. The Korean communities in Liaodong had refused to join the Red Turbans against the Yuan and in 1354, Gongmin of Goryeo contributed troops to Yuan efforts to suppress the Red Turbans. The invasions caught the unprepared Goryeo forces off guard, causing much destruction, sacking several cities, and briefly occupying Pyongyang (1359) and Kaesong (1360). Although ultimately repelled, the havoc caused by the Red Turbans on Goryeo was substantial.[14]

Southern Red Turbans

[edit]In the summer of 1351, Peng Yingyu and his principal military follower, Zou Pusheng, found in Xu Shouhui, a cloth peddler, the makings of a Red Turban figurehead. In September, Zou captured the city of Qishui in southern Hubei and enthroned Xu Shouhui as emperor over the Red Turban dynasty of "Tianwan" (Heaven Consummated). The new dynasty expanded southward and briefly held Hanyang, Hankou, and Wuchang before being driven off in 1352. In 1355, Zou was succeeded by Ni Wenjun as military leader. Ni took Hanyang again in 1356 and moved the dynasty's capital there. The next year, Ni attempted to murder Xu and replace him but failed. He was executed and replaced by Chen Youliang. Under Chen, the dynasty's territories rapidly expanded and in less than two years, had taken Chongqing and held all of Sichuan. In 1360, Chen murdered Xu and seized the throne, renaming the dynasty to Han. He immediately launched an attack on Nanjing but failed to take it and was forced to return to Wuchang, which he made his capital. Chen attacked Zhu Yuanzhang and was defeated, being ejected from Jiangxi in 1361. Chen made a final attempt at defeating Zhu in 1363, sending a large armada down the Changjiang into Lake Poyang. Chen and Zhu's forces engaged in a long running battle lasting over the summer before Chen was defeated and killed after suffering an arrow wound to the head. Zhu then took Han Lin'er, who had been Chen's ward since the death of Liu Futong.[12]

In Sichuan, the Red Turban commander, Ming Yuzhen, refused to acknowledge Chen Youliang when he usurped Xu Shouhui. Ming declared his own Red Turban kingdom of Ming Xia. He seemed to have governed competently, having recruited scholars and heeding the advice of a Confucian official named Liu Zhen, but failed in an attempt to take Yunnan from the Mongols. Ming reigned until he died of illness at the age of 35 in 1366. He was succeeded by his son, Ming Sheng, who surrendered to the Ming dynasty in 1371.[15]

Historical records commonly portray the Red Turban Army as dealing with captive Yuan officials and soldiers with considerable violence. In his work on violence in rural China, William T. Rowe writes:[16]

The Red Army brutally killed every Yuan official it could lay its hands on: in one instance, the History of Yuan reports, the army flayed an official alive and cut out his stomach. The Red Army was equally merciless toward captured Yuan soldiers: according to contemporary observer Liu Renben, Tianwan troops dealt with these demonized enemies by "placing them in shackles, poking them with knives, binding them with cloth, putting sacks over their heads, and parading them around accompanied by drum-beating and derisive chants".

Zhang Shicheng

[edit]Zhang Shicheng was a boatman from the market settlement of Bojuchang (modern Dafeng District) in northern Jiangsu. He engaged in transportation of illegal salt trade. In 1353, at the age of 32, Zhang killed one of the rich merchants who had cheated him and set fire to the local community. Then with his brothers and a group of 18 followers, Zhang fled and turned to banditry. Within a few weeks Zhang had recruited more than ten thousand followers, whom he led to plunder Taizhou and other nearby cities. By the end of 1353, Zhang had taken the city of Gaoyou. In the summer of 1357, Zhu Yuanzhang captured Zhang Shicheng's brother, Shide, and tried to use him to bargain for Zhang's surrender. Shide secretly sent a letter to his brother telling him to surrender to the Yuan instead, then starved himself to death in prison. Zhang accepted titles from the Yuan court later that year but was de facto still independent. Under the conditions laid out, Zhang was supposed to send a million piculs of rice to Khanbaliq every year by sea, but the Yuan capital never received more than 15% of the agreed amount. In 1363, Zhang took control of Hangzhou and declared himself Prince of Wu. Zhang attacked Zhu Yuanzhang but failed to defeat him and in 1364, Zhu also declared himself Prince of Wu. By late autumn of 1365, Zhu had taken the offensive position against Zhang. Zhang was besieged at Suzhou from 27 December 1366 until 1 October 1367, when its defenses fell. Zhang was captured and sent to Nanjing, where he hanged himself in his cell.[17]

Fang Guozhen

[edit]Fang Guozhen was from Huangyan district on the coast of central Zhejiang. He was illiterate and his family were shipowners who dealt in coastal trade. In 1348, Fang was accused of dealing with pirates, so he killed his accuser and fled to offshore islands with three brothers and local cohorts. He gained a large following with over a thousand vessels under his command. He controlled the prefectures of Jingyuan, Taizhou, and Wenzhou, and practically the entire Zhejiang coast from Ningbo to northern Fujian. He also held de facto control over Ningbo and Shaoxing. He made a living as a pirate until 1356, when he surrendered to the Yuan court and was awarded titles. He helped transport grain for Zhang Shicheng to the Yuan capital, Khanbaliq. In 1359, Zhang sent a son to Zhu Yuanzhang as hostage. In 1367, Fang surrendered to Zhu Yuanzhang on favorable terms. Fang stayed in Nanjing until 1374, when he died of natural causes.[18]

Ming dynasty (Zhu Yuanzhang)

[edit]

Zhu Yuanzhang, who would later become the Hongwu Emperor, was born on 21 October 1328 at Zhongli village in Haozhou (modern Fengyang County, Anhui). He was the youngest surviving child among four sons and two daughters. His parents were tax defaulters who fled from place to place working as tenant farmers. At the age of 16, in 1344, Zhu's father, mother, and oldest brother died in an epidemic accompanied by summer locusts and drought. The surviving family was too poor to care for Zhu and offered him to a local Buddhist monastery as menial labour. Zhu was sent out by the monastery to beg for food. For the next three years Zhu wandered around as a mendicant monk, during which time he came to understand the circumstances of the rebellion. At the age of 24, Zhu returned to the monastery where he learned to read and studied Buddhist texts.[19]

On 16 February 1352, Haozhou was captured by the Red Turbans. The Yuan army retaliated by sending raiders to sack Buddhist monasteries, turning Zhu's home into a battlefield. His temple was burned down in the same month. On 15 April, Zhu joined the Red Turban rebellion under Guo Zixing's command. Zhu married an adopted daughter of Guo who would later become empress. In 1353, two other rebels on the run from Yuan forces took refuge with Guo, but asserted seniority over him and caused factional conflict within the rebel movement. Guo was captured by one of the rebel leaders and was saved by Zhu upon his return from an expedition. A Yuan siege on Haozhou was also ended when their general, Jia Lu, died. Afterwards, Zhu returned to his village and recruited over 700 men led by 24 of his friends, which included figures such as Xu Da, Chang Yuchun, Tang He, Lan Yu, Mu Ying and Geng Bingwen. They were known as the "Fengyang mafia".[20][21][22]

In the fall of 1353, Guo gave Zhu an independent commission under the title of guard commander. He expanded south, gaining large numbers of followers and defected soldiers along the way. By the end of the year, Zhu had gained Chuzhou (near the Anhui–Jiangxi border) and remained there until 1355, when he had amassed an army of 30,000. After successfully repelling a Yuan army in the first months of 1355, at which point Guo Zixing had died, Zhu started preparations to attack Nanjing. The siege in mid-August was a failure but Zhu's forces remained stable and took the surrounding countryside. In October, the Red Turbans tried to take Nanjing again, and in the process both of Guo's successors were killed, leaving Zhu Yuanzhang in sole command of his forces.[23]

His background was genuinely that of the poorest level of the "oppressed masses". His education was rudimentary, and he shared no common ground with the traditional governing stratum. But he was convinced by his early literati assistants that he too, on the model of the founder of the Han dynasty at the end of the third century B.C. (whose origins, although not as humble as Chu's, made him a close model), could become a sage emperor.[24]

On 10 April 1356, Zhu took Nanjing, made it his new capital, and renamed it Yingtian (Response to Heaven). The court of Han Lin'er of the new Song dynasty awarded Zhu with titles and named him the head of Jiangxi. Zhu accepted the titles and Han Lin'er as emperor, legitimizing himself as a representative of a 'revived' Song dynasty and the 'Luminous King' described in White Lotus teachings. A few things set Zhu apart from his rebel counterparts. He did not challenge the past legitimacy of the Mongol Yuan dynasty and only noted that by his time, the Mongols no longer possessed it. When enemy military leaders and civilians succumbed to Zhu's forces, he gave them honorable burials and established shrines in their memory.[25] Zhu insisted that he was not a rebel, and he attempted to justify his conquest of the other rebel warlords by claiming that he was a Yuan subject divinely-appointed to restore order by crushing rebels. Most Chinese elites did not view the Yuan's Mongol ethnicity as grounds to resist or reject it. Zhu emphasised that he was not conquering territory from the Yuan dynasty but rather from the rebel warlords. He used this line of argument to attempt to persuade Yuan loyalists to join his cause.[26]

Zhu progressively developed his following into a working state. Zhu personally traveled to regions that had been conquered to survey problems and actively recruited scholars and officials, whom he invited to dine with him in his headquarters. In March 1358, he assigned Kang Maocai, a former Yuan official who had surrendered, to the Superintendency of the Office for Hydraulic Works to repair dikes and embankments. In 1360, he established bureaus to tax wine, vinegar, and salt, even though he did not control the primary salt-producing regions to the east. In 1361, he began minting copper coins, and by 1363, 38 million coins were being produced in one year. In 1362, custom offices were set up to collect taxes on traditional and commercial goods.[27]

In 1363, Zhang Shicheng attacked the Song court in Anfeng. Zhu personally led his army to defend them against Zhang and while Liu Futong was killed, Zhu managed to save Han Lin'er, whom he moved to Chuzhou where the Song court continued to exist in safety. In the same year, Zhu won the Battle of Lake Poyang against his rival Chen Youliang, and proceeded to eliminate Zhang Shicheng and Fang Guozhen. He spent most of 1364 and 1365 consolidating the territory he absorbed from his victory over Zhang.[28] Zhu continued to use the Song's reign period as his official calendar until Han Lin'er drowned while crossing the Changjiang in January 1367, possibly by design. Calling to overthrow the "barbarians" and restore the "Chinese", Zhu gained popular support.[29] A calendar called that of the Great Ming dynasty, beginning on 20 January 1368, was promulgated. On 12 January 1368, Zhu Yuanzhang proclaimed himself emperor (Hongwu Emperor) of the Ming dynasty (Radiant dynasty) in Yingtian.[30]

On 15 August 1368, the Ming general Xu Da led an army north from Kaifeng. A defending army was defeated and Tongzhou, an intermediate city on the way to Khanbaliq, was captured on 10 September. The Yuan emperor Toghon Temür fled to Shangdu. Khanbaliq fell to the Ming on 14 September, ending the rule of the Yuan dynasty. The city was renamed Beiping (Pacified North).[31] Shangdu was taken by the Ming general Chang Yuchun on 20 July 1369, forcing Toghon Temür to flee further north to Karakorum.[32] China proper was once again under ethnic Han rule.

Yuan forces

[edit]Toqto'a

[edit]Toqto'a was the primary decision maker behind the Yuan throne starting in 1340 after taking power in a coup supported by the emperor Toghon Temür. As chancellor, he supported Confucian forms of government and sought to stabilize the realm through vigorous government action. One of his efforts in this endeavor was to repair and extend the Grand Canal so that the capital, Khanbaliq, could be securely supplied with grain grown in the Changjiang delta. The project's failure in addition to a slew of natural disasters drew harsh criticism from his detractors, leading to his resignation in June 1344. In the summer of 1344, the Yellow River shifted its course, causing droughts in the Huai River valley. Toqto'a's successor, Berke Bukha, had no answer to the crisis, which was exacerbated by the coastal rebellion of Fang Guozhen, whose fleet interdicted most of the grain shipments headed for the capital. In August 1349, Toqto'a returned to power with the support of the emperor. In April 1351, Toqto'a tried once again to tame the Yellow River and Grand Canal through the mass mobilization of rural farmers, leading to the Red Turban Rebellion.[33] After initial rebel victories, the Yuan armies were able to rally and suppress most of the Red Turbans by 1353. In October 1353, Toqto'a personally recovered Xuzhou, forcing the rebels Peng Da and Zhao Junyong to flee to Haozhou.[34] Toqto'a was dismissed in January 1355 due to court intrigue while he was successfully campaigning against Zhang Shicheng. After his removal, the offensive against Zhang fell apart, and the Yuan court lost the last vestige of control it held over its own military forces.[35][36]

Chaghan Temur

[edit]Chaghan Temur was a fourth generation descendant of a Naiman clan that had settled in Shenqiu on the eastern border of Henan. Chaghan Temur's great-grandfather assisted the Mongol conquest of China in the 13th century. Although originally Turkic, by the time of the Red Turban Rebellions, Chaghan Temur's lineage more closely aligned with both Mongol and Chinese culture. Chaghan Temur once sat the imperial examinations and sometimes used the surname Li. In the late 1340s, Chaghan Temur built a military force to protect his locality from the rebels. Starting in 1352, he won a string of victories against the Red Turbans and for a time in 1358 and 1359, based his operations in Kaifeng. By the end of the 1350s, Chaghan Temur was the most powerful regional leader under the Mongols' service.[36]

Chaghan Temur's rival, Bolad Temür, the commander of Shanxi, refused to aid him. Bolad Temur's efforts to overthrow Chaghan Temur and destroy Köke Temür paralyzed the court until his death in 1365. As a result, Chaghan Temur ignored orders from the court and moved troops of his own will. Chaghan Temur was assassinated in 1362 by Tian Feng and Wang Shicheng, two former Yuan generals who then fled to join the rebels.[37]

Köke Temür

[edit]Köke Temür, originally named Wang Baobao, was the adopted son and nephew of Chaghan Temur through his sister. Wang Baobao received the name Köke Temür from Toghon Temür in 1361 when he delivered a shipment of grain to the capital. He succeeded his adoptive father when he died in 1362. Upon his father's death, Köke Temür was tasked with retaking Shandong from the rebels. He besieged the rebel base at Yidu and after several months, brought it down by tunneling under the walls. He captured the assassins of Chaghan Temur, Tian Feng and Wang Shicheng, and sacrificed them to his father's spirit. Meanwhile, due to Bolad Temur's machinations at court to remove crown prince Ayushiridara, Köke Temür remained estranged from court. Bolad Temur and Köke Temür engaged in open warfare in Shanxi, which turned in Köke Temür's favor in 1363. Bolad Temur fled to the capital and seized control of it himself in 1364. Bolad Temur was assassinated in August 1365, after which Köke Temür escorted Ayushiridara back to the capital, where he remained for some time before returning to Henan.[38]

Köke Temür went to war with Li Siqi, Zhang Liangbi, Törebeg, and Kong Xing. The latter three being former associates of Bolad.[39] The emperor ordered Köke Temür to ignore them and defend the north from the Ming dynasty, but Köke Temür ignored his orders. In February 1368, Köke Temür was dismissed from office, and the other warlords ordered to crush him. Köke Temür won the subsequent battles and remained the strongest warlord in the north. Köke Temür came into conflict with the Ming anyways and was defeated in battle on 26 April. Khanbaliq fell to the Ming on 20 September. The Yuan emperor fled to Köke Temür, who took his remaining forces and retreated into Mongolia.[40] The other warlords in the northwest refused to cooperate with Köke Temür even as they fell one by one to the Ming. On 3 May, Ming forces led by Xu Da found Köke Temür in eastern Gansu. The Mongol forces were more numerous than anticipated so the Ming troops took up a defensive position behind a stream. Köke Temür attacked and outflanked the southwestern wing of the Ming army, very nearly routing them. However the Ming army managed to rally and counterattacked successfully the next day, destroying the Mongols. Despite his losses, Köke Temür escaped total destruction and remained active in the desert. Meanwhile, Toghon Temür died at Yingchang on 23 May 1370 while his son, Biligtü Khan Ayushiridara, fled further into Mongolia. Ayushiridara's son, Maidarbal, and 5,000 Mongol warriors were captured by the Ming.[41]

In 1372, an anti-Mongol army 150,000 strong was assembled under Xu Da, Li Wenzhong, and Feng Sheng. Xu Da marched across the Gobi Desert in search of Köke Temür. On 23 April, a Ming division caught a part of the Mongol army by the Tuul River and defeated it, causing Köke Temür to avoid combat for the next month. After marching fruitlessly in search of the Mongols, the Ming army was defeated in an engagement on 7 June. Xu Da took the remaining survivors and retreated from Mongolia. In early July, Li Wenzhong encountered another Mongol force under Manzi Kharajang by the Tuul River and pursued them to the Orkhon River. The Mongols turned to face them and counterattacked with unexpected force, causing the Ming army to take the defensive position. The Ming soldiers slaughtered their livestock and used their corpses as a line of defense. The Mongols withdrew and Li was able to retreat. Feng Sheng successfully cleared the path westward to Dunhuang and retook the Hexi Corridor for the Ming.[42]

In November 1373, Köke Temür tried to take Datong. He suffered a disastrous defeat against Xu Da, who force marched his army through a snowstorm to attack the Mongol forces on 29 November. Köke Temür died in September 1375 at Khara Nokhai, northwest of Karakorum.[43]

Li Siqi

[edit]Li Siqi was a friend of Chaghan Temur who participated in the early military campaigns of the latter against the Red Turbans. By the end of the 1350s Li had become the dominant local power in Shaanxi.[36] After Chaghan Temur's death, Li refused to acknowledge Köke Temür as Chaghan Temur's successor and went to war with him.[39] Li surrendered to the Ming dynasty on 21 May 1369.[32]

Chen Youding

[edit]Chen Youding was born to an illiterate farmer's family in Fuzhou. Orphaned at an early age, he joined the military in the 1350s and was given charge of a police detachment. However his military capabilities far outstripped his station and he became chief of the provincial government within 10 years. He ruled with an iron hand which drove many of his subordinates to defect. When captured by Zhu Yuanzhang in 1368, Chen continued to show belligerence, bellowing at the Ming emperor, "The state is demolished and my family is gone. I shall die; what more is there to talk about?"[44] He and his son were executed.[44]

At the end of the Yuan, bandits arose in all places. Among the common people volunteer forces were formed to protect village and locality. Those who called themselves commanders of such forces were too numerous to count. The Yuan government granted them official ranks and titles at the drop of a hat. Thereafter some would go off to become bandits; others served the Yuan cause but without resolve. Chen Youding and his son, however, died for righteousness. People of the time praised them for that consummation of their principles.[45]

He Zhen

[edit]He Zhen was an orphan who nonetheless received an education in both brush and sword. He held office in government briefly before leading a local defense corps. He succeeded in recapturing a local prefectural city from bandits and was rewarded with office in the prefecture. In 1363 he led provincial armies to recapture Guangzhou from pirates. He became head of the provincial government in 1366. When the Ming armies approached in 1368, he readily gave up his position and surrendered. After an interview with Zhu Yuanzhang in Nanjing, he was awarded with honors and posts in the provincial government. He Zhen retired at the age of 65 in 1387 and was made hereditary earl.[46]

Basalawarmi

[edit]Basalawarmi, the Prince of Liang, and head of government in Yunnan, committed suicide when the region was conquered by the Ming dynasty in 1382. Yunnan played no major role in the events of the 1350s and 1360s.[46]

Naghachu

[edit]Naghachu was a Mongol leader captured by Zhu Yuanzhang in 1355. He was released in the hope of creating good will with the Mongols, but he left to create an independent Mongol military establishment in Liaodong. He remained a constant source of trouble until he was defeated in 1387. Naghachu was granted a marquisate and died on 31 August 1388, probably from alcohol abuse.[46][47]

Mass relocations

[edit]Following the victory, Zhu Yuanzhang ordered mass relocations across China. People from Shanxi were deported into other provinces in northern China including Hebei, Henan and Shandong which had been devastated by plague and famine.[48][49][50][51][52] Zhu Yuanzhang moved people from Shandong, Guangdong, Hebei, Shanxi and Lake Taihu to settle in his hometown of Fengyang, around 500,000 people in 1367. Guizhou and Yunnan were colonized by soldiers from Anhui, Suzhou and Shanghai from Nanjing numbering 100,000. Sichuan was resettled by people from Hubei and Hunan, Hubei and Hunan were resettled by people from Jiangxi and Henan, Shandong, Beijing, Hezhou and Chuzhou were resettled by people from Shanxi and western Zhejiang while northern Henan and Hebei was resettled by people from Shanxi.[53] The migration has been remembered in legends and novels.[54] Fengyang was resettled by people from southern China[55] and Jiangnan.[56]

See also

[edit]- Ispah Rebellion

- Battle of Lake Poyang

- Ming–Mong Mao War

- Ming campaign against the Uriankhai

- Battle of Buir Lake

- Jingnan campaign

- Battle of Kherlen

- Yongle Emperor's Northern campaigns

References

[edit]- ^ Mote 1988, p. 16.

- ^ Mote 1988, p. 12.

- ^ Mote 1988, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Mote 1988, p. 26.

- ^ Robinson 2009, p. 134.

- ^ Yuan dynasty: Ancient China Dynasties, para. 3.

- ^ Brook, Timothy (1999). The Confusions of Pleasure: Commerce and Culture in Ming China (illustrated, reprint ed.). University of California Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0520221543.

- ^ Sussman, George D. (2011), "Was the Black Death in India and China?", Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 85 (3), CUNY La Guardia Community College: 319–355, doi:10.1353/bhm.2011.0054, PMID 22080795, S2CID 41772477

- ^ Dreyer 1988, p. 58.

- ^ Mote 1988, pp. 37–38.

- ^ Mote 1988, p. 39.

- ^ a b Mote 1988, pp. 39–40.

- ^ Mote 1988, p. 43.

- ^ Robinson 2009, pp. 147–159.

- ^ Mote 1988, pp. 41–42.

- ^ Rowe, William. Crimson Rain: Seven Centuries of Violence in a Chinese County. 2006. p. 53

- ^ Mote 1988, pp. 30–35.

- ^ Mote 1988, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Mote 1988, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Tsai, Shih-shan Henry (2011). Perpetual Happiness: The Ming Emperor Yongle. University of Washington Press. pp. 22, 64. ISBN 978-0295800226.

- ^ Adshead, S. A. M. (2016). China In World History (illustrated ed.). Springer. p. 175. ISBN 978-1349237852.

- ^ China in World History (3rd, illustrated ed.). Springer. 2016. p. 175. ISBN 978-1349624096.

- ^ Mote 1988, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Mote 1988, p. 49.

- ^ Mote 1988, pp. 47–51.

- ^ David M. Robinson (2019). In the Shadow of the Mongol Empire: Ming China and Eurasia. Cambridge University Press. pp. 144–146. ISBN 978-1108682794.

- ^ Mote 1988, p. 54.

- ^ Dreyer 1988, p. 89.

- ^ Chan, Hok-Lam (2008). "The 'Song' Dynasty Legacy: Symbolism and Legitimation from Han Liner to Zhu Yuanzhang of the Ming Dynasty". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 68 (1): 91–133. ISSN 0073-0548. JSTOR 40213653.

- ^ Mote 1988, pp. 51–57.

- ^ Langlois 1988, p. 113.

- ^ a b Langlois 1988, p. 117.

- ^ Dreyer 1988, pp. 59–60.

- ^ Dreyer 1988, p. 62.

- ^ Dreyer 1988, p. 63.

- ^ a b c Mote 1988, p. 20.

- ^ Mote 1988, p. 21.

- ^ Mote 1988, pp. 21–23.

- ^ a b Mote 1988, p. 23.

- ^ Dreyer 1988, p. 96.

- ^ Dreyer 1988, p. 100.

- ^ Dreyer 1988, pp. 102–103.

- ^ Langlois 1988, p. 129.

- ^ a b Mote 1988, p. 24.

- ^ Mote 1988, p. 29.

- ^ a b c Mote 1988, p. 25.

- ^ Langlois 1988, p. 158.

- ^ "Land of fairy tales". China Daily (Hong Kong ). 23 Jun 2012.

- ^ "Chinese Mass Migrations: Past, Present & Future". China Simplified. January 22, 2016.

- ^ Brook, Timothy (1999). The Confusions of Pleasure: Commerce and Culture in Ming China (illustrated, reprint ed.). University of California Press. p. 269. ISBN 978-0520221543.

- ^ Chinese Geography and Environment, Volume 1, Issue 2 – Volume 3, Issue 2. M.E. Sharpe, Inc. 1988. pp. 11, 12.

- ^ Li, Nan (March 2018). "The Long-Term Consequences of Cultural Distance on Migration: Historical Evidence from China". Australian Economic History Review. 58 (1). Economic History Society of Australia and New Zealand and John Wiley & Sons Australia, Ltd: 2–35. doi:10.1111/aehr.12134.

- ^ Wang, Fang (2016). Geo-Architecture and Landscape in China's Geographic and Historic Context: Volume 1 Geo-Architecture Wandering in the Landscape (illustrated ed.). Springer. p. 275. ISBN 978-9811004834.

- ^ Yan, Lianke (2012). Lenin's Kisses: A Novel. Open Road + Grove/Atlantic. ISBN 978-0802193940.

- ^ He, H. (2016). Governance, Social Organisation and Reform in Rural China: Case Studies from Anhui Province (illustrated ed.). Springer. ISBN 978-1137484697.

- ^ Lu, Hanchao (2005). Street Criers: A Cultural History of Chinese Beggars (illustrated ed.). Stanford University Press. pp. 57–59. ISBN 978-0804751483.

Bibliography

[edit]- Dreyer, Edward L. (1988). "Military origins of Ming China". In Mote, Frederick W.; Twitchett, Denis (eds.). The Cambridge History of China, Volume 7: The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644, Part 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 58–108. ISBN 978-0-521-24332-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Langlois, Jr., John D. (1988). "The Hung-wu reign, 1368–1398". In Mote, Frederick W.; Twitchett, Denis (eds.). The Cambridge History of China, Volume 7: The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644, Part 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 107–181. ISBN 978-0-521-24332-2.

- Mote, Frederick W. (1988). "The rise of the Ming dynasty, 1330–1367". In Mote, Frederick W.; Twitchett, Denis (eds.). The Cambridge History of China, Volume 7: The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644, Part 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 11–57. ISBN 978-0-521-24332-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Robinson, David M. (2009). Empire's Twilight: Northeast Asia Under the Mongols. Harvard-Yenching Institute monograph series. Vol. 68. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-03608-6.

External links

[edit] Media related to Red Turban Rebellion at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Red Turban Rebellion at Wikimedia Commons