Culture of the Ming dynasty

The Ming dynasty (1368–1644) of China was known for its advanced and cultured society. The culture of the Ming dynasty was deeply rooted in traditional Chinese values, but also saw a flourishing of fine arts, literature, and philosophy in the late 15th century.

During this time, the government played a stronger role in shaping culture, requiring the use of Zhu Xi's interpretation of Neo-Confucianism in civil service examinations and promoting "proper" art in literature and painting. Despite this, some historians view the Ming era as a period of monotony and mediocrity.[1] However, the Ming dynasty was actually a time of great creativity, particularly in its final century. Intellectuals of this time sought self-realization through anti-rationalist individualism, as seen in the teachings of Wang Yangming, and pursued wisdom through the cultivation of knowledge of one's own mind.[2]

During the early Ming period, painting and calligraphy were heavily influenced by past styles, particularly those of the Song dynasty, but were also transformed in a creative manner. The court painting academy, which was revived in the 1420s and 1430s, focused on the genre of "flowers and birds". This genre was dominated by renowned masters such as Bian Jingzhao (early 15th century) and Lin Liang (late 15th century). Meanwhile, landscape painting, which was more popular among independent artists, saw the rise of the Wu School led by founder Shen Zhou and the Zhe school, with Dai Jin as its most prominent representative. In the 16th century, there was a prevalence of imitating traditional techniques and subjects in painting. However, Lü Ji stood out in the "flowers and birds" genre for his mastery. Along with the aforementioned artists, Tang Yin, Wen Zhengming, and others also gained recognition during the Ming period. One of the defining characteristics of this period was the fusion of painting and calligraphy, with works from the 15th century onwards containing an equal balance of both art forms.

During the late 14th and early 15th centuries, there was a prevalent tendency among literary and journalistic works to imitate old patterns. This was particularly evident in the works of the "adherents of old literature", such as Song Lian, Liu Ji, Yang Shiqi, and other politicians and scholars. In the Ming period, a variety of literary works were produced, including fiction, science, and practical texts. The most notable and representative works of this period were multi-volume encyclopedic works and anthologies. While works written in classical Chinese were primarily intended for the gentry, colloquial literature and drama had a much wider audience among literate Chinese with less education. One of the most famous novels of the Ming period, Jin Ping Mei, was published in 1610 and is considered the fifth of the great Chinese novels, following the "Four Classic Novels". Two of these classics, Water Margin and Journey to the West, were also written during the Ming period.

The Ming dynasty saw the emergence of four-act zaju plays, which were popular during the previous Yuan era. However, the more popular plays were the multi-act chuanqi plays, which underwent significant changes in their accompanying music until the kunqu style became dominant. In terms of imagery, Ming dramatists were on par with novelists. One of the most renowned plays in Chinese history, The Peony Pavilion, was written by Tang Xianzu, a dramatist from the end of the Ming era.

Among the architectural marvels of the Ming dynasty, the most significant ones include the imperial residence—the Forbidden City, the Temple of Heaven complex in Beijing, the set of imperial tombstones in Shisanling, and last but not least, the Great Wall of China.

Calligraphy

[edit]Early and Middle Ming period

[edit]

During the first decades of the Ming dynasty, the imperial court highly esteemed and valued leading calligraphers. Some notable names among them were Song Ke (1327–1387), Shen Du (1357–1434), and Shen Can (1379–1453).[3] The emperors themselves also held a deep appreciation for calligraphy. The Yongle Emperor (reigned 1402–1424) was particularly fond of it and even designated the style of the two Wangs (Wang Xizhi and his son Wang Xianzhi from the 4th century) as the official script. His successor, the Hongxi Emperor, was renowned for his calligraphy skills and was often compared to the Tang Emperor Taizong (reigned 626–649). In the mid-1420s, the following Ming emperor, the Xuande Emperor, restored the Imperial Academy of Painting and Calligraphy in Beijing, which then set the standard for art in the first half of the Ming period.[4]

In the mid-fifteenth century, there was a decline in royal interest in calligraphy.[3] As a result, the focus of artistic activity shifted to southeastern China during the mid-Ming period.[4] This led to the emergence of new trends in calligraphy among the artists and literati[3] of wealthy cities such as Jiangnan, particularly Suzhou and Songjiang. While Ming calligraphers were influenced by the styles of the old masters and often referenced them, they tended to only adopt the form without delving deeply into the substance.[5]

Some notable calligraphy masters from Jiangnan include Zhang Bi (1425–1487) from Songjiang, who specialized in "crazy conceptual writing" in the style of Tang calligraphers Zhang Xu and Huaisu,[5] and Li Dongyang (1447–1516),[5] a Grand Secretary who was renowned for his seal script and also excelled in clerical script.[6]

In the second half of the 15th century, under Shen Zhou, calligraphers from Suzhou revived the styles of the Northern Song masters. Shen Zhou was not only an excellent painter,[6] but also a skilled calligrapher. He based his conceptual script on the style of the Northern Song calligrapher Huang Tingjian, using plump and rounded strokes that were written with a sense of haste. This style was also followed by Shen's student Wen Zhengming.[3] Another influential figure in the calligraphy world at the time was Wu Kuan (吳寬), Minister of Rites, who followed the style of another Northern Song artist, Su Shi. During this period, the accompanying inscriptions on literati paintings held a significance similar to the paintings themselves.[6] Calligraphy was often the primary focus, with painting being added as a secondary element.[7]

Zhu Yunming (1460–1526) and Wen Zhengming[8] were both members of the younger generation in Suzhou. Zhu Yunming was the grandson of the renowned scholar and calligrapher Xu Youzhen, and the son-in-law of another esteemed calligrapher, Li Yingzhen (李應禎).[7] He was particularly skilled in small regular script,[3] but it was his "crazy conceptual script" that earned him the most admiration, which he turned to after failing his examinations.[8] His friends believed that Zhu Yunming's impulsive personality was reflected in his highly expressive calligraphy.[3]

Wen Zhengming was a master of poetry, calligraphy, and painting. Despite failing the civil service examinations ten times, he was able to support himself through his art. He excelled in small regular script and seal script in calligraphy, but also studied and practiced other styles. He was influenced by famous calligraphers such as Zhao Mengfu. Many of his works have been preserved.[9] Wen Zhengming had numerous students and followers, including his sons Wen Peng and Wen Jia, who were both skilled painters known for their delicately colored landscapes. Wen Peng gained recognition for his conceptual script and became famous for his seal carving. Another student of Wen Chengming was the painter Chen Chun, who was also known for his conceptual script in calligraphy.[10]

Late Ming period

[edit]

The theory and practice of late Ming calligraphy was heavily influenced by Dong Qichang (1555–1636) of Songjiang, a renowned scholar who excelled in literary composition, painting, and calligraphy from a young age. He was not only a prominent theorist of painting, but also wrote about the history of calligraphy, placing the masters of his Songjiang region above those of Suzhou.[11] Dong emphasized the importance of studying works from the Eastern Jin (4th century) and Tang (7th–9th centuries),[3] particularly the Wangs,[11] but did not advocate for direct imitation of their styles. Instead, he encouraged a thorough analysis of their most significant techniques.[3]

In the second half of the 16th century, there were several important Songjiang calligraphers, including Chen Jiru, a versatile artist and collector who was a friend of Dong Qichang, and Xu Wei, a pioneer of individual artists in the Qing dynasty. Xu Wei was known for his "flower and bird" paintings and also wrote calligraphy in the "crazy conceptual script", which had a style similar to abstract painting. In the first half of the 17th century, Chen Hongshou, a calligrapher and professional painter specializing in figure painting, gained recognition for his unique expression, which continued to be admired in the years to come.[12]

The last generation of Ming calligraphers had distinct and unique styles. Contemporary critics, as well as the calligraphers themselves, used the term qi to describe the innovative calligraphy of the period. This term can be translated as "unusual" or "strange", and it refers to the radical deviation from traditional norms of composition and handwriting. One notable calligrapher of this time was Wang Duo (1592–1652), who claimed that his style was inspired by the work of classical masters. Despite the seemingly chaotic appearance of his writing, Wang Duo's personal and inventive style aligns with Dong Qichang's belief that calligraphy should not simply copy, but rather creatively transform the patterns of the past.[3]

Painting

[edit]The Ming era was significant in preserving a large number of paintings by renowned masters, as well as thousands of works by lesser-known artists. In contrast, the Song era only has a few surviving original works by well-known artists, and none from the Tang era.[13] Ming painters were known for their diverse styles,[13] but they often drew inspiration from Tang patterns. In fact, Ming critics considered this style to be "Tang traditions", as it was more realistic compared to the philosophical and lyrical appearance of the Song period, and the formal and abstract appearance of the Yuan era.[14]

Academy

[edit]After the establishment of the Ming dynasty, the influence of southern artistic styles, seen as a reflection of the country's spirit and culture, grew. Concurrently, the practice of professional official art was revived within the imperial court.[15] However, independent court painters held little significance during the early Ming period and worked independently. Notable figures among them include Ma Wan (mid-14th century) and Wang Fu (1362–1416), who were renowned for their bamboo ink paintings.[16] They were succeeded by Xia Chang in the latter half of the 15th century.[17]

| After the establishment of the Ming dynasty in 1368, the Hongwu Emperor gathered a group of literati, painters, and calligraphers in the Belvedere of Literary Profundity. The main task assigned to the painters was to decorate the imperial palaces. However, it was not until the beginning of the Xuande Emperor's reign (1425–1435) that the actual imperial painting academy (畫院; huayuan) was established. This academy was named after the era of Xuande and is known as the Imperial Painting Academy of the Xuande era (宣德畫院; Xuande huayuan). Its model was based on the office of the same name that operated during the Song dynasty.[18] |

Early Ming painting was heavily influenced by the past, particularly the patterns of the Song dynasty.[19] This restorationist movement was rooted in a conservative approach to the past, which was already evident in the painters of the previous Yuan period. The restorationist ideology was most prominently embodied in the painting academy, which was reinstated by the Xuande Emperor in the mid-1420s.[20]

The restoration of the academy in Beijing resulted in a revival of the rules and style of the Song imperial painting academy, as well as a shift in focus from the southern to the northern Song academic tradition.[20] The court artists were given the responsibility of reviving the splendor of Tang and Song period art (7th–9th and 10th–13th centuries). Their task was to create elaborate celebratory pieces with a decorative purpose, in order to "rekindle old traditions" and commemorate the country's prosperity. To achieve this goal, the artists created specific guidelines for the subject matter, techniques, and styles of painting.[20] They drew inspiration from the works of Ma Yuan (active c. 1190–1264), Xia Gui (first half of the 13th century), which were collectively known as the "Ma–Xia style", as well as Guo Xi (c. 1020–1070) and green-blue landscapes.[3]

The genre of "flowers and birds" held a significant position in Ming academic art. Similar to the Song models, the court painters of this genre divided into two directions. One direction was the dynamic ink painting of Lin Liang, who was active in the second half of the 15th century and drew inspiration from the work of Xu Xi from the 10th century. Lin Liang's style involved using ink without contour lines, creating a "boneless" effect. In contrast, the other direction was represented by Lü Ji, who focused on descriptive realism. Lü Ji carefully delineated contours and used color techniques influenced by Huang Quan (903–968).[3]

Notable academics included Bian Jingzhao, Li Zai (both in the first half of the 15th century), and Lin Liang.[21] The aesthetic principles of the academy were best expressed by Dong Qichang in his theoretical works.[20] Dong emphasized the idea of painting as a form of calligraphy and promoted the creation of a "grand synthesis" (da cheng) of artistic style through the study of past masters. In order to legitimize his own artistic performances, he claimed that in past centuries, painters always belonged to one of two stylistic schools: the ink paintings of the southern school, which aimed to express the inner essence of the subject, and the descriptive, decorative tradition of professional "artisan" painters of the northern school.[3] He positioned himself as the culmination of the southern school's development, as the true heir of literary painting that strives to express the ideas of the creator rather than seeking material gain. His monumental ink landscapes became the standard of orthodoxy,[11] and the concept of the northern and southern schools was only reevaluated in the 20th century.[10] Dong Qichang's student, Wang Shimin, also followed the orthodox Qing painting style, as did Shitao and Bada Shanren.[22]

Zhe and Wu schools

[edit]

In and around Hangzhou, there were professional painters who loosely followed the Ma–Xia style and were known as the "Zhe School" (named after the province of Zhejiang, where Hangzhou was the capital). One of the leading representatives of this school was Dai Jin, who returned to Hangzhou at the beginning of the 15th century after being expelled from the court.[3] He focused on figure painting, as well as paintings of "flowers and birds", but his main focus was on landscapes in a Yuan interpretation of the Ma–Xia style.[15]

The Zhe School was an informal group primarily composed of professionals[15] who supplemented the painting academy in the capital. Upon retiring from their official careers, they returned to their native south. Due to their connection with the academy, their work tended to be conservative and eclectic, with a strong emphasis on decorative elements. The most significant figure in the school after its founder was Lan Ying (1585–1664), a professional landscape painter.[23]

In the latter half of the Ming dynasty, the academy's prestige declined.[24] The hub of artistic innovation shifted to the affluent Jiangnan region (located south of the lower Yangtze River), with Suzhou as its epicenter. This area attracted a large concentration of intellectuals who prioritized artistic self-expression over pursuing a government position. These intellectuals were commonly referred to as the Wu School, named after the region's former designation. The Wu School, despite its name, was not a cohesive movement, but rather included a diverse group of artists, both amateur and professional. Its founder, Shen Zhou, was a multi-talented artist known for his calligraphy, painting, poetry, and collecting.[24] He was heavily influenced by the expressionist style of the Yuan masters[3] and often painted grand landscapes in the Song style, following the examples of Dong Yuan[6] and Juran. Shen Zhou also excelled in figure painting and the "flower and bird" genre.[25] One of his students, Wen Zhengming, continued his legacy and was joined by other talented artists such as Wen Boren, Qian Gu, Lu Zhi, Zhang Ling (張靈), and Chen Chun. Among them, Wen Zhengming and Chen Chun were the most prominent and representative of the Wu School.[26] Wen Zhengming's paintings were characterized by monochrome or lightly colored landscapes in the style of Shen Zhou, as well as "green-blue landscapes" in the Tang style.[9] The Wu School is credited with reviving the tradition of southern amateur painting.[26] Chen Chun, on the other hand, brought originality to the "flower and bird" genre.[27]

Artists outside of schools, portraits, illustrations

[edit]

Many artists, such as Tang Yin (1470–1523), Qiu Ying (1525–1593), and Xu Wei (1521–1593), were influenced by the Wu school and worked in and around Suzhou.[28] However, they were not officially part of the school. Tang Yin and Qiu Ying often alternated between self-expression and academic style. They, along with other artists from the Zhe and Wu schools, were considered part of the conservative wing of the southern tradition or the southern direction of academicism. On the other hand, Xu Wei broke away from academicism and created freely and independently. His paintings were characterized by a deliberate carelessness and simplification of form, resulting in exceptional credibility and expressiveness in his compositions.[29] Qiu Ying's works were more popular with the public than literary painting, leading to many merchants signing his name on paintings that were often far from his actual style.[30]

Chen Hongshou was a notable figure painter during the late Ming period. His work was characterized by original depictions of landscapes and figures, which was also seen in the works of his contemporaries Ding Yunpeng and Wu Bin.[17]

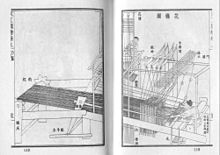

The Ming period saw a flourishing of portrait art, with many portraits of officials and their ancestors depicted in official robes. However, this genre was often overlooked by literary critics, who saw it as a commercial pursuit rather than a form of artistic expression.[30] One of the new developments in 16th-century art was the rise of funeral portraits, which were known for their realistic depictions. As the amount of printed literature increased, the genre of book illustrations, primarily woodcuts, also became popular. Qiu Ying, a prominent artist of the time, perfected the distinctive style of miniatures in this field in the mid-16th century.[31] The 17th century saw the emergence of color book illustrations as well.[32]

Poetry

[edit]Late 14th and early 15th centuries

[edit]The poetry of the 14th century was heavily influenced by Late Tang patterns, but towards the end of the century, there was a shift in interest towards the Early and High Tang periods, as well as the older yuefu ballads.[33] Gao Qi is widely regarded as the greatest poet of the 14th century, and even of the entire Ming period. He was from Suzhou and was already recognized as a talented literati in his youth.[34] After the establishment of the Ming dynasty, he briefly served in the historical office before returning to Suzhou. In 1374, he was accused of treason and subsequently executed. As a poet, he was versatile, composing yuefu ballads, sao (騷) style poems, shi poetry, ci songs, and qu arias.[34] His contributions to literary theory are also noteworthy.[35] He held a high regard for Tang poetry from the so-called "High Tang period".[33]

The purges carried out by the Ming founder Hongwu Emperor resulted in the deaths of many literati, and the government's strict control over literary production may have contributed to the lack of great poets during the 15th century.[35] For example, out of the "Four Outstanding Talents of Suzhou" during the early Ming dynasty, Gao Qi was executed, Yang Ji (楊基; c. 1334–1383) died from hard labor, Zhang Yu (張羽; 1283–after 1356) drowned while returning from exile, and only Xu Ben (徐賁; 1335–1380) died of natural causes. It is worth noting that, apart from Gao, the other three were also renowned painters.[36] Among the scholars during the Hongwu Emperor's reign, Liu Ji gained the most recognition for his contemplative poems, while Song Lian was primarily known as a prose-writer.[36]

In the early Ming dynasty, there were multiple regional centers of poetry. The second most significant center, after Jiangnan, was located in Fujian.[37] The most prominent local figure was Lin Hong (林鴻; ca. 1340–1400), but his student Gao Bing was of even greater importance. In 1393,[33] Gao Bing compiled the Tangshi Pinhui (唐詩品彙; Graded Collocation of Tang Poetry), an anthology of approximately six thousand Tang poems. These poems were evaluated and classified according to the ideas of Southern Song critic Yan Yu. Gao Bing divided Tang poetry into four periods: Early, High, Middle, and Late. He considered the High Tang era to be the highest, but also recognized the value of the Early Tang period as it led to the development of the High Tang era. The Late Tang period was considered to be of lower quality because it was further removed from the High Tang era. Gao Bing's views gained influence in the late 15th century and were widely cited.[38] His division of Tang poetry remained in use until the 21st century.[33]

During the reign of the Yongle Emperor (1402–1424), the capital was moved to Beijing, and with it, literary life became concentrated there. Beijing academics in high official positions dominated the literary world, led by the "Three Yangs" (Yang Rong, Yang Shiqi, and Yang Pu), as well as Wang Zhi, Jin Youzi, Xie Jin, and Zeng Qi. Their poetry was known as "cabinet-style poetry" (taige ti), and their prose was simple and direct, reminiscent of the style of the Song dynasty. Another notable figure in this generation was Minister of War Yu Qian,[38] although he was more renowned for his political actions than his poetic achievements.[39]

From the late-15th century

[edit]

After Beijing, the most important center of culture was Suzhou. With the economic rise of Jiangnan at the end of the 15th century, it also gave birth to a constellation of scholars, some of whom even reached high positions in the government, such as Wu Kuan and Wang Ao. The natives of Suzhou excelled in painting, with notable artists such as Shen Zhou, a painter and poet. The art of Suzhou continued to flourish in the next generation with artists like Yang Xunji (楊循吉), Zhu Yunming, Tang Yin, and Wen Zhengming. However, unlike their predecessors, these artists did not have significant official careers. They were instead known as calligraphers, painters, and poets of the so-called fugu (复古; 'revive antiquity') direction, which focused on archaizing admiration and a return to old patterns.[39]

Before the fugu movement, Li Dongyang was a prominent figure.[33] However, he faced opposition from the "Earlier Seven Masters of the Ming"—Li Mengyang, He Jingming (何景明), Bian Gong (邊貢), Wang Tingxiang (王廷相), Kang Hai, Wang Jiusi and Xu Zhenqing (徐禎卿). All of them, except for Xu Zhenqing, was from northern China and were heavily influenced by Li Mengyang.[a] Their goal was to elevate poetry beyond mere technical skill, which was Li Dongyang's focus. They looked to the Han and Wei poets for old-style (guti) poetry and the High Tang poets for new-style (xinti) poetry. During the reign of the Hongzhi Emperor (1487–1505), the favorable political climate allowed them to take their roles as officials, poets, and philosophers more seriously and refine their views through discussions at their meetings in the capital. However, after 1505, when the new regime of the Zhengde Emperor came into power, the "Seven" gradually lost their positions in the capital and dispersed to their homes.[40] Some, like He Jingming in 1511, later returned to Beijing. He Jingming then had his own disciples, including Zheng Shanfu and Xue Hui (薛蕙). Gu Lin (顧璘) remained active in the south and was later followed by He Liangjun (何良俊), Huangfu Fang (皇甫汸), and the "Latter Seven Masters".[41]

Yang Shen, the son of the renowned Grand Secretary Yang Tinghe, was a prolific author of both prose and poetry. He was also a highly esteemed scholar in various fields. In 1424, he was sent to Yunnan by the emperor, at the same time as his father was removed from office. While Yang Shen was not directly associated with the archaizing movement, his poetry was heavily influenced by the poets of the Six Dynasties and the Late Tang. His wife, Huang E (1498–1569), is considered by many to be the greatest poetess of the Ming era.[41]

The trend of returning to traditional poetic styles began before the middle of the 16th century, led by Xie Zhen, a southerner who had failed in his career and embraced the individualistic ideas of He Jingming. Other notable poets in this movement, known as the "Latter Seven Masters of the Ming", included Li Panlong (李攀龍), Wang Shizhen (王世貞), Xu Zhongxing, Liang Youyu, Zong Chen, and Wu Guolun (吳國倫). Li Panlong's collection of Tang poetry, Tangshi xuan (唐詩選; 'Selection of Tang Poems'), was particularly significant as it became the primary source for readers in Japan and China to appreciate Tang poetry. Wang Shizhen, one of the "Latter Seven Masters", was considered the greatest poet among them, partly due to the vast number of his poems.[42]

Literature

[edit]In classical language

[edit]

During the early Ming period, there was a tendency among literati to imitate old patterns. This is evident in the works of authors such as Song Lian, Liu Ji, Yang Shiqi, and many other officials and scholars who are classified as "followers of old literature" (guwen pai).[19] From the 14th to the 16th century, the literary language used by these writers took on a more bookish tone, with the authors incorporating phrases from classical books and limiting the use of colloquial language. One notable novelist during this time was Qu You (1341–1427), known for his short story collection, New Stories to Trim the Lamp By.[43] The form of the short stories was based on the Tang chuanqi, and the author incorporated traditional folklore motifs.[44] This collection gained widespread popularity and elevated the short story with supernatural elements to an artistic genre. However, it faced criticism from Confucian moralists who deemed it as "useless stories" due to its focus on the miraculous and supernatural, and sometimes even political themes.[43] Despite this, it also gained significant popularity in Japan, Korea, and Vietnam, where it became the defining work of the short story genre. Following Qu You's work, Li Zhen (李禎; 1376–1452) continued the tradition with his work, More Stories Written While Trimming the Lamp (剪燈餘話; Jiandeng Yuhua), in which he reworked traditional plots.[44] The genre continued to thrive in the following decades, with Shao Jingchan (邵景詹) following in the footsteps of Qu You at the end of the 16th century.[45]

Ming scholars were known for their diverse range of essays and reflections on various subjects. Among these, the works of Gui Youguang (1506–1571) on daily life and the philosophical writings of Wang Yangming were particularly esteemed.[46] One notable prose genre during this period was the "eight-legged essay", which became a requirement for civil service examinations starting in the late 15th century.

The Ming period is best known for its extensive collection of multi-volume encyclopedic works and anthologies,[46] both state-owned (such as the Yongle Encyclopedia) and private (such as the Compendium of Materia Medica from the late 16th century). The Compendium of Materia Medica contains 1,892 medicinal plants, over 11 thousand regulations, and more than 1100 illustrations. In addition to these encyclopedic works, Ming intellectuals also produced geographical texts (such as Xu Xiake's Travels), historical works (Song Lian and Wang Shizhen), and linguistic works and dictionaries.[47]

In colloquial language

[edit]

Works written in classical Chinese were only fully comprehensible to members of the gentry. However, literate Chinese with less education, such as women from educated families, merchants, and lower officials, made up a disproportionately large audience for colloquial (baihua) literature and drama.[48] Feng Menglong (1574–1646) specifically emphasized the accessibility and significance of literature in baihua.[49] Short stories and novellas written in a language close to colloquialism, known as huaben, were highly popular. From the 15th century, writers began to imitate these works, which were referred to as ni huaben (擬話本; 'imitation story scripts').[50] In the 16th century, huaben short stories and novels dominated the literary scene. Publishers released numerous individual short stories and anthologies, as well as new editions of works by Song and Yuan authors, their imitations, and new stories. These collections often had a thematic focus, but were mostly diverse.[49]

The novel was closely related to the short story, analogous in style and means of expression,[51] but in contrast to the short story consisting of dozens of chapters. The subjects of the novels came from stories circulated among storytellers in the city markets for centuries.[52] A variety of genres were popular: the success of Luo Guanzhong's historical novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms[53] was followed by a flood of historical prose in which real events mingled with fantasy.[54] Shi Nai'an's Water Margin was the most popular representative of the heroic and adventurous epic. In addition to Romance of the Three Kingdoms and Water Margin, the four classic Chinese novels also include the fantastic Journey to the West.[55] Journey to the West was followed by a number of epigones, and in the 16th century, Xu Zhonglin's Investiture of the Gods was popular, as well as Luo Maodeng's account of Zheng He's voyages, The Eunuch Sanbao's Voyage to the Western Ocean.[56] Detective novels, whose protagonist was an honest judge, were also widespread.[55] Of the Ming novels describing everyday life, the most important is Jin Ping Mei, published in 1610,[56] which became the fifth of the great Chinese novels immediately after the "four classic novels".

Useful literature and newspapers

[edit]

In addition to poetry and fiction, Ming publishers also produced a significant amount of useful literature. This included travel guides that described routes around the country, as well as "travel notes" written by members of the gentry who enjoyed traveling.[57][58] During the late Ming period, a new genre emerged—moral guides that summarized advice for merchants on business ethics and lifestyle.[59] In hopes of achieving commercial success, Ming publishers also released handbooks on a variety of topics, ranging from funeral customs to multiplication tables to contract templates and dream dictionaries. They even published syllabaries for children and "pocket classics" for students.[52] As a result, European visitors in the 16th and 17th centuries were amazed by the abundance and affordability of books in China.[60]

The first mention of a newspaper in Beijing dates back to 1582, and by 1638, newspapers were already being printed using movable type, replacing the previous method of carving entire pages on wooden boards.[61] Ming publishers were pioneers in book production, and in the first half of the 17th century, Wu Faxiang introduced blind printing to create a plastic effect.[62][63] Hu Zhengyan also made significant advancements in color printing.[64][65]

Drama

[edit]Early Ming period

[edit]The four-act zaju plays, which were the main form of Yuan drama, continued to be popular during the Ming dynasty. It is known that there were 520 plays written by a hundred different authors during this time.[66] However, Ming authors focused more on creating multi-act plays called chuanqi,[46][67] which were developed from the Song "southern plays" (nanxi). The accompanying music also underwent significant changes until the kunqu style became dominant.[67]

The authors of dramas were primarily men of letters during the Ming dynasty. However, there were some lower-status dramatists who emerged in the early days of the dynasty, but their works were often rejected. This was due to the belief that only the educated were capable of being successful authors. As a result, Ming drama was largely created by and for the elite, in contrast to the Yuan era. This trend was further reinforced by government regulations, such as the 1373 ban on actors portraying monarchs, their concubines, loyal courtiers, and noble patriots and sages from all dynasties, except for those who were considered models of proper behavior.[68] Additionally, works that contained slander against monarchs and sages were also prohibited from being performed or printed. While these prohibitions were not always strictly enforced, Ming drama was generally not known for its direct political and social criticism, unlike Yuan drama.[69]

Due to the concentration of population and wealth in the southern region of China, southern art forms dominated the country.[69] These included the dramatic form of chuanqi,[b] which originated from the southern dramas of the Song period.[70]

During the transition from Yuan to Ming, several chuanqi plays emerged, including the renowned "four great chuanqi plays". However, there was a noticeable gap in the production of these plays after this period. This could possibly be attributed to the civil war of 1399–1402 and the relocation of the capital to the north (from Nanjing to Beijing).[71] Another factor could be the departure of literati into civil service, which was in contrast to the Yuan period.[72]

The popularity of zaju persisted even after the fall of the Yuan dynasty, thanks to the efforts of two Ming princes during the early years of the Ming dynasty. These princes were Zhu Quan, the seventeenth son of the Hongwu Emperor,[66] and the Hongwu Emperor's grandson, Zhu Youdun (朱有燉).[73] Zhu Quan is credited with about fifty literary works, including twenty plays. However, only two of his works have survived—one about the pursuit of immortality and the other about a young scholar who elopes with a beautiful widow, only to eventually marry her with her father's consent. These works are highly regarded for their elegant style. Zhu Quan is also known for compiling the Taihe zhengyin pu (The Table of Correct Sounds of the Great Peace Era),[66] although it is believed that this work was actually compiled by one of his subordinates in the 1430s or 1440s. This work contains a list of 689 zaju plays, commentaries on dramatic poetry by various authors, and 335 melodies for zaju.[73] Zhu Youdun, on the other hand, was the most prolific playwright of the first half of the 15th century. He wrote over thirty zaju plays, all of which were published. His works were often performed during court festivities, holidays, and anniversaries. Some of his plays featured elaborate stage designs with multiple troupes of dancers and singers, as well as special effects. Another group of Zhu Youdun's plays focused on classical zaju, with a central theme of praising a loyal courtier. He also wrote comedies that satirized dishonest merchants and disloyal courtiers.[74] The success of these high-ranking members of the ruling dynasty inspired other authors to write zaju plays. However, after the first third of the 15th century, interest in zaju declined.[71]

From the second half of the 15th century to the middle of the 17th century

[edit]

In the second third of the 15th century, there was a gap in the production of chuanqi plays. However, the first recorded chuanqi play after this gap was written by Qiu Jun (1421–1495), a respected official and scholar. According to modern historian John Hu, his only surviving play is considered terrible.[72] Despite this, Qiu Jun's dedication to the chuanqi genre inspired others to also write in this style. However, many of his successors were more focused on showcasing their scholarly knowledge rather than creating original and creative works.[72] Only a few exceptional works were produced, such as Xiuruji (Story of the embroidered coat) attributed to Xu Lin (徐霖; 1462–1538), which tells the story of a young official and a prostitute.[75]

The popularity of zaju declined after Zhu Youdun, but it was revived in the early 16th century by Kang Hai and Wang Jiusi, who were inspired by their love for the genre.[76] Following them, Li Kaixian (1502–1568) and Xu Wei, also known as a painter, dedicated themselves to writing drama.[42]

In the second half of the 15th century, authors began to experiment with different regional musical styles (such as Haiyan, Yuyao, Yiyang, and Kunshan) in search of a suitable musical accompaniment for the southern plays and chuanqi. Eventually, southern music prevailed over northern music.[75] By the end of the 16th century, Liang Chenyu (梁辰魚) achieved success with kunqu music, leading to the merging of the terms chuanqi and kunqu.[77] Shen Jing (沈璟; 1553–1610) formulated the rules of composition, emphasizing the harmony of melodies, and his students formed the renowned Wujiang school.[78] However, other authors placed greater emphasis on artistic spontaneity and ingenuity. One of the most successful of these was Tang Xianzu (1550–1617) of Jiangxi, an official who lived in poverty during the last two decades of his life.[79] Despite his circumstances, Tang wrote one of the most famous plays in Chinese history, The Peony Pavilion.

After Tang Xianzu and Shen Jing, literati began to embrace drama as a respected art form. Legal restrictions were no longer a hindrance, resulting in a surge of new authors and plays.[80] These plays were often adaptations of older stories and themes, typically with a happy ending. The focus was on the form rather than the content of the story, resulting in stereotypical characters. Notable authors during this time included Ruan Dacheng, who wrote nine kunqu plays,[80] and Wu Bing (吳炳), a respected minister who authored five kunqu plays.[81]

Porcelain, cloisonné, and lacquer products

[edit]Large-scale state production of porcelain was already well-established during the Yuan dynasty and continued under the Ming dynasty. However, the first Ming emperor, the Hongwu Emperor, implemented a ban on unlicensed foreign trade. As a result, the import of cobalt, which was used to dye blue and white porcelain, from Muslim countries ceased. To compensate for this loss, Ming porcelain factories turned to using a red copper glaze. During the Hongwu era, multicolored pottery was not commonly produced.[82]

However, with the revival of foreign trade during the reign of the Yongle Emperor, the import of cobalt resumed. This cobalt was low in manganese, resulting in a bright blue color. Along with the traditional blue and white porcelain, the Ming factories also produced wares with red, brown, and gold glazes. These wares often featured combinations of green patterns on a yellow background, or brown on green.[82]

During the reign of the Xuande Emperor (1425–1435), blue and white porcelain reached its peak of quality. It became so renowned that later Chinese and Japanese manufacturers attempted to pass off their products as being from the Xuande era, in an attempt to claim perfection.[83] The majority of this porcelain was produced in Jingdezhen, located in Jiangxi province. This complex became China's largest center for ceramic and porcelain manufacturing[3] and was a major supplier to the court during the mid-fifteenth century.[84] The Xuande era also saw the rise of the best Ming cloisonné, which gained popularity in the 15th century.[85] Additionally, colored porcelain of the doucai (contrasted colors) type emerged during this time, with blue-and-white patterns being colored in red, yellow, green, or purple.[82] While the style of porcelain remained relatively unchanged for the rest of the 15th century, there was a slight decline in artistic level during the middle third of the century. However, excellent pieces from the Chenghua era (1465–1488) were still preserved[82] and multi-colored decor became more widespread.[86]

During the reign of the Jiajing Emperor (1524–1566), the production of state porcelain factories was insufficient to meet the needs of the imperial court. As a result, the government began to order goods from private manufacturers. The court's high standards for quality led to an increase in the level of private porcelain factories, allowing them to cater to the demands of wealthy and discerning customers. The variety of patterns also expanded, with a significant increase in the use of lucky symbols in private porcelain factories. This period also saw the emergence of five-color porcelain, known as wucai, which became widely popular during the Wanli era (1573–1620). However, by the end of the Wanli era, the quality of porcelain processing had somewhat declined compared to its early days.[82]

During the late Ming period, private workshops emerged as the main hubs of creativity and production, replacing state-run porcelain factories. In Fujian and Guangdong, coarse pottery was commonly produced.[82] One notable example is Dehua in Fujian province, renowned for its unique white porcelain pottery and figurines. This type of pottery gained popularity in Europe during the seventeenth century and came to be known as "Blanc de Chine". In Shanxi province, family workshops specialized in creating ceramic figurines adorned with "three colors" (sancai) glazes.[3] By the early 17th century, certain masters in the field of porcelain-making gained recognition for their exceptional skills, such as He Chaozong, renowned for his exquisite white porcelain figurines.

Lacquerware was highly valued and significant in Chinese art.[86] The most exceptional pieces were created during the 15th century, particularly during the Yongle and Xuande eras. A variety of techniques were utilized for decoration, including relief, marquetry, and painted lacquer. The southern region, particularly Fujian, was known for producing exquisite lacquer products.[87]

Architecture

[edit]

In architecture, the Ming dynasty adhered to traditional patterns, despite the fact that Song and Tang architecture were more innovative and grand. However, there are several notable buildings that have survived from the Ming period.[88] The most significant architectural project during the early Ming period was the construction of the capital city, first in Nanjing and later in Beijing. In Beijing, the imperial residence, known as the Forbidden City, was particularly noteworthy. The largest burial complexes were the tombs of the emperors in Nanjing and Beijing. In the early 15th century, the Yongle Emperor oversaw the restoration of the Grand Canal.

Under the influence of Tibetan and Indian architecture, a new type of Buddhist temple emerged known as the "diamond throne pagoda", in which several pagodas are built on a shared platform. The oldest known example of this style is the Zhenjue Temple in Beijing, which was completed in 1473. In contrast, mosque buildings during the Ming period were solely based on Chinese architectural traditions. This is evident in the Great Mosque in Xi'an, which dates back to the early Ming period and only displays Muslim influences in its interior decoration.[89]

In the 16th century, the construction of the Temple of Heaven complex in Beijing and the nearby imperial tombs continued. This period saw the emergence of a new architectural style, characterized by grandeur and refinement. Examples of this style can be seen in the construction of the Forbidden City, the Temple of Confucius in Qufu, and the buildings on the sacred Buddhist mountain of Wutaishan in Shaanxi province. The architecture of prosperous villages is also documented through monuments in Sidi and Hongcun.

In the 16th century, the Great Wall of China underwent a restoration project that extended over 2,400 km, stretching from Shanhai Pass on the coast of the Yellow Sea to Jiayu Pass on the western border of Ming China.[90] Along with the restoration of the wall, the construction of fortresses was also a significant undertaking, as seen in the walls of Nanjing and Pingyao.

Ming sculpture saw a decline in quality compared to previous eras.[91] While there are still many preserved Buddhist statues and sculptures made of bronze, wood, and lacquer, they lack the expressive power seen in Tang and Song works. Even the stone sculptures found in the imperial tombs show a decrease in liveliness and technical skill. On the other hand, small statuettes made of jade, ivory, or porcelain maintained a high level of artistry.[91] Among these, the most prized are the white porcelain (Blanc de Chine) statuettes from Fujian.[88]

The art of garden composition was developed, following the principles of feng shui. Architects distinguished between northern and southern styles of gardens and parks; the former was characterized by large dimensions and vibrant colors, while the latter was known for its modesty and monochromatic design.[92] Over time, the relationship between buildings and gardens shifted. While gardens were previously seen as a complement to buildings, in the late Ming period, buildings began to be placed within gardens, with the buildings becoming a subordinate element. This shift transformed gardens into social and cultural gathering places, attracting art and patronage. This new model of the private garden had a significant impact.[3] Towards the end of the Ming period, the first theoretical treatise on garden and park construction was published—The Craft of Gardens by Ji Cheng in 1634.[93]

Notes

[edit]- ^ His influence also extended to other writers, such as Cui Xian (崔銑; 1478–1541) and Gu Lin (1476–1545).

- ^ Chuanqi were originally known as "marvel tales" during the Tang dynasty, and the term was later used for dramas during the late Yuan dynasty. Over time, the dramas of chuanqi and zaju became distinct, and during the early Qing dynasty, they were contrasted with each other.[69]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Liščák (2003), p. 297, Mingská Čína.

- ^ Liščák (2003), pp. 297–298, Mingská Čína.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q "Ming dynasty 1368–1644". Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Art Museum (PUAM). Archived from the original on 10 February 2014. Retrieved 12 June 2014.

- ^ a b Zádrapa & Pejčochová (2009), p. 241.

- ^ a b c Zádrapa & Pejčochová (2009), p. 242.

- ^ a b c d Zádrapa & Pejčochová (2009), p. 244.

- ^ a b Zádrapa & Pejčochová (2009), p. 245.

- ^ a b Zádrapa & Pejčochová (2009), p. 246.

- ^ a b Zádrapa & Pejčochová (2009), p. 247.

- ^ a b Zádrapa & Pejčochová (2009), p. 248.

- ^ a b c Zádrapa & Pejčochová (2009), p. 249.

- ^ Zádrapa & Pejčochová (2009), p. 250.

- ^ a b Munsterberg (1989), p. 172.

- ^ Munsterberg (1989), p. 173.

- ^ a b Kravtsova (2004), p. 628.

- ^ Kravtsova (2004), p. 629.

- ^ a b Wang (2008), p. 183.

- ^ Кравцова, М.Е. "Сюань-дэ хуа-юань" (in Russian). Синология.Ру. Retrieved 14 June 2014.

- ^ a b Rybakov (1999), pp. 528–546.

- ^ a b c d Kravtsova (2004), p. 631.

- ^ Kravtsova (2004), p. 632.

- ^ Wang (2008), p. 184.

- ^ Kravtsova (2004), pp. 628–629.

- ^ a b Kravtsova (2004), p. 633.

- ^ Wang (2008), p. 177.

- ^ a b Kravtsova (2004), p. 634.

- ^ "Water and Ink Flowing with Feeling: The Painting and Calligraphy of Chen Chun: Exhibit Info". Taipei: National Palace Museum. Retrieved 9 January 2014.

- ^ Kravtsova (2004), p. 636.

- ^ Kravtsova (2004), p. 637.

- ^ a b Munsterberg (1989), p. 174.

- ^ Rybakov (2000), p. 299.

- ^ Ebrey (1996), p. 204.

- ^ a b c d e Bryant (2001), p. 403.

- ^ a b Wixted (2001), p. 396.

- ^ a b Wixted (2001), p. 397.

- ^ a b Wixted (2001), p. 398.

- ^ Bryant (2001), p. 400.

- ^ a b Bryant (2001), p. 401.

- ^ a b Bryant (2001), p. 402.

- ^ Bryant (2001), p. 404.

- ^ a b Bryant (2001), p. 406.

- ^ a b Bryant (2001), p. 407.

- ^ a b Titarenko (2008), p. 89.

- ^ a b Titarenko (2008), p. 90.

- ^ Titarenko (2008), p. 91.

- ^ a b c Liščák (2003), p. 299, Mingská Čína.

- ^ Liščák (2003), p. 300, Mingská Čína.

- ^ Ebrey (1996), pp. 202–203.

- ^ a b Titarenko (2008), p. 94.

- ^ Titarenko (2008), p. 93.

- ^ Titarenko (2008), p. 95.

- ^ a b Ebrey (1996), p. 202.

- ^ Titarenko (2008), p. 99.

- ^ Titarenko (2008), p. 97.

- ^ a b Titarenko (2008), p. 98.

- ^ a b Titarenko (2008), pp. 101–102.

- ^ Needham (1986), p. 524.

- ^ Hargett (1985), p. 69.

- ^ Brook (1998), pp. 215–217.

- ^ Ebrey (1996), p. 201.

- ^ Brook (1998), p. 171.

- ^ Eliot & Rose (2007), p. 107.

- ^ Fan (2014), pp. 205–206.

- ^ "Hu Zhengyan". China Culture.org. China Daily. 2003. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ^ Thomas, Ebrey. "The Editions, Superstates and States of the Ten Bamboo Studio Collection of Calligraphy and Painting" (PDF). East Asian Library and Gest Collection, Princeton University. pp. 1–9. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ^ a b c Hu (1983), p. 77.

- ^ a b Hu (1983), p. 60.

- ^ Hu (1983), p. 61.

- ^ a b c Hu (1983), p. 62.

- ^ Hu (1983), p. 63.

- ^ a b Hu (1983), p. 67.

- ^ a b c Hu (1983), p. 68.

- ^ a b Hu (1983), p. 78.

- ^ Idema & West (2012), p. 105.

- ^ a b Hu (1983), p. 69.

- ^ Bryant (2001), p. 399.

- ^ Hu (1983), p. 71.

- ^ Hu (1983), p. 72.

- ^ Hu (1983), p. 73.

- ^ a b Hu (1983), p. 75.

- ^ Hu (1983), p. 76.

- ^ a b c d e f "History of Oriental Ceramics: A View of Chinese ceramics". The Museum of Oriental Ceramics,Osaka. Osaka: The Museum of Oriental Ceramics. 2009. Retrieved 20 June 2014.

- ^ Munsterberg (1989), p. 189.

- ^ Munsterberg (1989), p. 178.

- ^ Munsterberg (1989), p. 192.

- ^ a b Munsterberg (1989), p. 190.

- ^ Munsterberg (1989), p. 191.

- ^ a b Munsterberg (1989), p. 176.

- ^ Titarenko (2010), pp. 43–44.

- ^ Ebrey (1996), p. 208.

- ^ a b Munsterberg (1989), p. 175.

- ^ Titarenko (2010), pp. 45–46.

- ^ Titarenko (2010), p. 59.

Works cited

[edit]- Brook, Timothy (2003). Čtvero ročních období dynastie Ming: Čína v období 1368–1644 (in Czech). Translated by Liščák, Vladimír (1st ed.). Praha: Vyšehrad. ISBN 80-7021-583-6.

- Zádrapa, Lukáš; Pejčochová, Michaela (2009). Čínské písmo (in Czech). Praha: Academia. ISBN 978-80-200-1755-0.

- Munsterberg, Hugo (1989). The Arts of China. Rutland, Vermont: Charles E. Tuttle. ISBN 978-1-4629-0295-8.

- Кравцова, Марина (2004). История искусства Китая: Учебное пособие (in Russian). СПб: «Лань», «TPHADA». ISBN 5-8114-0564-2.

- Wang, Yaoting (2008). Čínské malířství (in Czech). Praha: Euromedia Group - Knižní klub. ISBN 978-80-242-2239-4.

- Rybakov, Rostislav Borisovich (1999). "V. Между монголами и португальцами (Азия и Северная Африка в XIV-XV вв.). Китай во второй половине XIV-XV в. (Империя Мин)". История Востока. В 6 т:. Том 2. Восток в средние века (in Russian). Moskva: Институт востоковедения РАН.

- Rybakov, Rostislav Borisovich (2000). "Китай в XVI - начале XVII в.". История Востока. В 6 т:. Том 3. Восток на рубеже средневековья и нового времени. XVI-XVIII вв (in Russian). Moskva: Институт востоковедения РАН. ISBN 5-02-018102-1.

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley (1996). The Cambridge illustrated history of China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-43519-6.

- Wixted, John Timothy (2001). "Poetry of the Fourteenth Century". In Mair, Victor H (ed.). The Columbia History of Chinese Literature. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 390–398. ISBN 0-231-10984-9.

- Bryant, Daniel (2001). "Poetry of the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries". In Mair, Victor H (ed.). The Columbia History of Chinese Literature. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 399–409. ISBN 0-231-10984-9.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China. Vol. 3, Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and the Earth. Taipei: Caves Books.

- Hargett, James M (July 1985). "Some Preliminary Remarks on the Travel Records of the Song Dynasty (960-1279)". Chinese Literature: Essays, Articles, Reviews. ISSN 0161-9705.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Brook, Timothy (1998). The Confusions of Pleasure: Commerce and Culture in Ming China. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-22154-0.

- Eliot, Simon; Rose, Jonathan (2007). Companion to the History of the Book. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4443-5658-8.

- Fan, Jialu (2014). "The Four Great Inventions". In Lu, Yongxiang (ed.). A History of Chinese Science and Technology. Heidelberg: Springer. ISBN 978-3-662-44166-4.

- Hu, John (1983). "Ming Dynasty Drama". In Mackerras, Colin (ed.). Chinese Theater: From Its Origins to the Present Day. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. pp. 60–91. ISBN 0-8248-0813-4.

- Idema, Wilt L; West, Stephen H (2012). Battles, Betrayals, and Brotherhood. Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Publishing. ISBN 9781603849111.

- Титаренко, M.Л (2008). Ин-т Дальнего Востока. Духовная культура Китая : энциклопедия : в 5 т. (in Russian). Vol. 3. Литература. Язык и письменность. Москва: Восточная литература. ISBN 978-5-02-036348-9.

- Титаренко, M.Л (2010). Ин-т Дальнего Востока. Духовная культура Китая : энциклопедия : в 5 т. + доп. том (in Russian). Vol. 6. (дополнительный) Искусство. Москва: Восточная литература. ISBN 978-5-02-036382-3.

External links

[edit] Media related to Art of the Ming Dynasty at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Art of the Ming Dynasty at Wikimedia Commons