Radcliffe Line

| Radcliffe Line | |

|---|---|

| |

| Characteristics | |

| Entities | India Pakistan and Bangladesh |

| History | |

| Established | 17 August 1947 Partition of India |

| Notes | Named after Cyril Radcliffe, who demarcated the boundary line. |

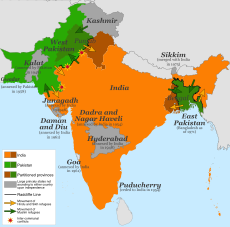

The Radcliffe Line was the boundary demarcated by the two boundary commissions for the provinces of Punjab and Bengal during the Partition of India. It is named after Cyril Radcliffe, who, as the joint chairman of the two boundary commissions, had the ultimate responsibility to equitably divide 175,000 square miles (450,000 km2) of territory with 88 million people.[1]

The term "Radcliffe Line" is also sometimes used for the entire boundary between India and Pakistan. However, outside of Punjab and Bengal, the boundary is made of existing provincial boundaries and had nothing to do with the Radcliffe commissions.

The demarcation line was published on 17 August 1947, two days after the independence of Pakistan and India. Today, the Punjab part of the line is part of the India–Pakistan border while the Bengal part of the line serves as the Bangladesh–India border.

Background

[edit]Events leading up to the Radcliffe Boundary Commissions

[edit]

On 18 July 1947, the Indian Independence Act 1947 of the Parliament of the United Kingdom stipulated that British rule in India would come to an end just one month later, on 15 August 1947. The Act also stipulated the partition of the Presidencies and provinces of British India into two new sovereign dominions: India and Pakistan.

Pakistan was intended as a Muslim homeland, while India remained secular. Muslim-majority British provinces in the northwest were to become the foundation of Pakistan. The provinces of Baluchistan (91.8% Muslim before partition) and Sindh (72.7%) and North-West Frontier Province became entirely Pakistani territory. However, two provinces did not have an overwhelming Muslim majority— Punjab in the northwest (55.7% Muslim) and Bengal in the northeast (54.4% Muslim).[2] After elaborate discussions, these two provinces ended up being partitioned between India and Pakistan.

The Punjab's population distribution was such that there was no line that could neatly divide the Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs. Likewise, no line could appease both the Muslim League, headed by Jinnah, and the Congress led by Jawaharlal Nehru and Vallabhbhai Patel.[citation needed] Moreover, any division based on religious communities was sure to entail "cutting through road and rail communications, irrigation schemes, electric power systems and even individual landholdings."[3]

Prior ideas of partition

[edit]The idea of partitioning the provinces of Bengal and Punjab had been present since the beginning of the 20th century. Bengal had in fact been partitioned by the then viceroy Lord Curzon in 1905, along with its adjoining regions. The resulting 'Eastern Bengal and Assam' province, with its capital at Dhaka, had a Muslim majority and the 'West Bengal' province, with its capital at Calcutta, had a Hindu majority. However, this partition of Bengal was reversed in 1911 in an effort to mollify Bengali nationalism.[4]

Proposals for partitioning Punjab had been made starting in 1908. Its proponents included the Hindu leader Bhai Parmanand, Congress leader Lala Lajpat Rai, industrialist G. D. Birla, and various Sikh leaders. After the 1940 Lahore resolution of the Muslim League demanding Pakistan, B. R. Ambedkar wrote a 400-page tract titled Thoughts on Pakistan.[5] In the tract, he discussed the boundaries of Muslim and non-Muslim regions of Punjab and Bengal. His calculations showed a Muslim majority in 16 western districts of Punjab and non-Muslim majority in 13 eastern districts. In Bengal, he showed non-Muslim majority in 15 districts. He thought the Muslims could have no objection to redrawing provincial boundaries. If they did, "they [did] not understand the nature of their own demand".[6][7]

After the breakdown of the 1945 Simla Conference of viceroy Lord Wavell, the idea of Pakistan began to be contemplated seriously. Sir Evan Jenkins, the private secretary of the viceroy (later the governor of Punjab), wrote a memorandum titled "Pakistan and the Punjab", where he discussed the issues surrounding the partition of Punjab. K. M. Panikkar, then prime minister of the Bikaner State, sent a memorandum to the viceroy titled "Next Step in India", wherein he recommended that the principle of 'Muslim homeland' be conceded but territorial adjustments made to the two provinces to meet the claims of the Hindus and Sikhs. Based on these discussions, the viceroy sent a note on the "Pakistan theory" to the Secretary of State for India .[8] The viceroy informed the Secretary of State that Jinnah envisaged the full provinces of Bengal and Punjab going to Pakistan with only minor adjustments, whereas Congress was expecting almost half of these provinces to remain in India. This essentially framed the problem of partition.[9]

The Secretary of State responded by directing Lord Wavell to send 'actual proposals for defining genuine Muslim areas'. The task fell on V. P. Menon, the Reforms Commissioner, and his colleague Sir B. N. Rau in the Reforms Office. They prepared a note called "Demarcation of Pakistan Areas", where they included the three western divisions of Punjab (Rawalpindi, Multan and Lahore) in Pakistan, leaving two eastern divisions of Punjab in India (Jullundur and Delhi). However, they noted that this allocation would leave 2.2 million Sikhs in the Pakistan area and about 1.5 million in India. Excluding the Amritsar and Gurdaspur districts of the Lahore Division from Pakistan would put a majority of Sikhs in India. (Amritsar had a non-Muslim majority and Gurdaspur a marginal Muslim majority.) To compensate for the exclusion of the Gurdaspur district, they included the entire Dinajpur district in the eastern zone of Pakistan, which similarly had a marginal Muslim majority. After receiving comments from John Thorne, member of the Executive Council in charge of Home affairs, Wavell forwarded the proposal to the Secretary of State. He justified the exclusion of the Amritsar district because of its sacredness to the Sikhs and that of Gurdaspur district because it had to go with Amritsar for 'geographical reasons'.[10][11][12][a] The Secretary of State commended the proposal and forwarded it to the India and Burma Committee, saying, "I do not think that any better division than the one the Viceroy proposes is likely to be found".[13]

Sikh concerns

[edit]This section may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: Relevance to the topic of the article is not clear. (July 2018) |

The Sikh leader Master Tara Singh could see that any division of Punjab would leave the Sikhs divided between Pakistan and India. He espoused the doctrine of self-reliance, opposed the partition of India and called for independence on the grounds that no single religious community should control Punjab.[14] Other Sikhs argued that just as Muslims feared Hindu domination the Sikhs also feared Muslim domination. Sikhs warned the British government that the morale of Sikh troops in the British Army would be affected if Pakistan was forced on them. Giani Kartar Singh drafted a scheme of a separate Sikh state if India was to be divided.[15]

During the Partition developments, Jinnah offered Sikhs to live in Pakistan with safeguards for their rights. Sikhs refused because they opposed the concept of Pakistan and also because they did not want to become a small minority within a Muslim majority.[16] Vir Singh Bhatti distributed pamphlets for the creation of a separate Sikh state "Khalistan".[17] Master Tara Singh wanted the right for an independent Khalistan to federate with either Hindustan or Pakistan. However, the Sikh state being proposed was for an area where neither religion was in absolute majority.[18] Negotiations for the independent Sikh state had commenced at the end of World War II and the British initially agreed but the Sikhs withdrew this demand after pressure from Indian nationalists.[19] The proposals of the Cabinet Mission Plan had seriously jolted the Sikhs because while both the Congress and League could be satisfied the Sikhs saw nothing in it for themselves. as they would be subjected to a Muslim majority. Master Tara Singh protested this to Pethic-Lawrence on 5 May. By early September the Sikh leaders accepted both the long term and interim proposals despite their earlier rejection.[18] The Sikhs attached themselves to the Indian state with the promise of religious and cultural autonomy.[19]

Final negotiations

[edit]

In March 1946, the British government sent a Cabinet Mission to India to find a solution to resolve the conflicting demands of Congress and the Muslim League. Congress agreed to allow Pakistan to be formed with 'genuine Muslim areas'. The Sikh leaders asked for a Sikh state with Ambala, Jalandher, Lahore Divisions with some districts from the Multan Division, which, however, did not meet the Cabinet delegates' agreement. In discussions with Jinnah, the Cabinet Mission offered either a 'smaller Pakistan' with all the Muslim-majority districts except Gurdaspur or a 'larger Pakistan' under the sovereignty of the Indian Union.[20] The Cabinet Mission came close to success with its proposal for an Indian Union under a federal scheme, but it fell apart in the end because of Nehru's opposition to a heavily decentralised India.[21][22]

In March 1947, Lord Mountbatten arrived in India as the next viceroy, with an explicit mandate to achieve the transfer of power before June 1948. Over ten days, Mountbatten obtained the agreement of Congress to the Pakistan demand except for the 13 eastern districts of Punjab (including Amritsar and Gurdaspur).[23] However, Jinnah held out. Through a series of six meetings with Mountbatten, he continued to maintain that his demand was for six full provinces. He "bitterly complained" that the Viceroy was ruining his Pakistan by cutting Punjab and Bengal in half as this would mean a 'moth-eaten Pakistan'.[24][25][26]

The Gurdaspur district remained a key contentious issue for the non-Muslims. Their members of the Punjab legislature made representations to Mountbatten's chief of staff Lord Ismay as well as the Governor telling them that Gurdaspur was a "non-Muslim district". They contended that even if it had a marginal Muslim majority of 51%, which they believed to be erroneous, the Muslims paid only 35% of the land revenue in the district.[27]

In April, the Governor of Punjab Evan Jenkins wrote a note to Mountbatten proposing that Punjab be divided along Muslim and non-Muslim majority districts and proposed that a Boundary Commission be set up consisting of two Muslim and two non-Muslim members recommended by the Punjab Legislative Assembly. He also proposed that a British judge of the High Court be appointed as the chairman of the commission.[28] Jinnah and the Muslim League continued to oppose the idea of partitioning the provinces, and the Sikhs were disturbed about the possibility of getting only 12 districts (without Gurdaspur). In this context, the Partition Plan of 3 June was announced with a notional partition showing 17 districts of Punjab in Pakistan and 12 districts in India, along with the establishment of a Boundary Commission to decide the final boundary. In Sialkoti's view, this was done mainly to placate the Sikhs.[29]

Process and key people

[edit]A crude border had already been drawn up by Lord Wavell, the Viceroy of India prior to his replacement as Viceroy, in February 1947, by Lord Louis Mountbatten. In order to determine exactly which territories to assign to each country, in June 1947, Britain appointed Sir Cyril Radcliffe to chair two boundary commissions—one for Bengal and one for Punjab.[30]

The commission was instructed to "demarcate the boundaries of the two parts of the Punjab on the basis of ascertaining the contiguous majority areas of Muslims and non-Muslims. In doing so, it will also take into account other factors."[31] Other factors were undefined, giving Radcliffe leeway, but included decisions regarding "natural boundaries, communications, watercourses and irrigation systems", as well as socio-political consideration.[32] Each commission also had four representatives—two from the Indian National Congress and two from the Muslim League. Given the deadlock between the interests of the two sides and their rancorous relationship, the final decision was essentially Radcliffe's.

After arriving in India on 8 July 1947, Radcliffe was given just five weeks to decide on a border.[30] He soon met with his fellow college alumnus Mountbatten and travelled to Lahore and Calcutta to meet with commission members, chiefly Nehru from the Congress and Jinnah, president of the Muslim League.[33] He objected to the short time frame, but all parties were insistent that the line be finished by the 15 August British withdrawal from India. Mountbatten had accepted the post as Viceroy on the condition of an early deadline.[34] The decision was completed just a couple of days before the withdrawal, but due to political considerations, not published until 17 August 1947, two days after the grant of independence to India and Pakistan.[30]

Members of the commissions

[edit]Each boundary commission consisted of five people – a chairman (Radcliffe), two members nominated by the Indian National Congress and two members nominated by the Muslim League.[35]

The Bengal Boundary Commission consisted of justices C. C. Biswas, B. K. Mukherji, Abu Saleh Mohamed Akram and S.A.Rahman.[36]

The members of the Punjab Commission were justices Mehr Chand Mahajan, Teja Singh, Din Mohamed and Muhammad Munir.[36]

Problems in the process

[edit]Boundary-making procedures

[edit]

All lawyers by profession, Radcliffe and the other commissioners had all of the polish and none of the specialized knowledge needed for the task. They had no advisers to inform them of the well-established procedures and information needed to draw a boundary. Nor was there time to gather the survey and regional information. The absence of some experts and advisers, such as the United Nations, was deliberate, to avoid delay.[37] Britain's new Labour government "deep in wartime debt, simply couldn't afford to hold on to its increasingly unstable empire."[38] "The absence of outside participants—for example, from the United Nations—also satisfied the British Government's urgent desire to save face by avoiding the appearance that it required outside help to govern—or stop governing—its own empire."[39]

Political representation

[edit]The equal representation given to politicians from Indian National Congress and the Muslim League appeared to provide balance, but instead created deadlock. The relationships were so tendentious that the judges "could hardly bear to speak to each other", and the agendas so at odds that there seemed to be little point anyway. Even worse, "the wife and two children of the Sikh judge in Lahore had been murdered by Muslims in Rawalpindi a few weeks earlier."[40]

In fact, minimizing the numbers of Hindus and Muslims on the wrong side of the line was not the only concern to balance. The Punjab Border Commission was to draw a border through the middle of an area home to the Sikh community.[41] Lord Islay was rueful for the British not to give more consideration to the community who, in his words, had "provided many thousands of splendid recruits for the Indian Army" in its service for the crown in World War I.[42] However, the Sikhs were militant in their opposition to any solution which would put their community in a Muslim ruled state. Moreover, many insisted on their own sovereign state, something no one else would agree to.[43]

Last of all, were the communities without any representation. The Bengal Border Commission representatives were chiefly concerned with the question of who would get Calcutta. The Buddhist tribes in the Chittagong Hill Tracts in Bengal had no official representation and were left totally without information to prepare for their situation until two days after the partition.[44]

Perceiving the situation as intractable and urgent, Radcliffe went on to make all the difficult decisions himself. This was impossible from inception, but Radcliffe seems to have had no doubt in himself and raised no official complaint or proposal to change the circumstances.[1]

Local knowledge

[edit]Before his appointment, Radcliffe had never visited India and knew no one there. To the British and the feuding politicians alike, this neutrality was looked upon as an asset; he was considered to be unbiased toward any of the parties, except of course Britain.[1] Only his private secretary, Christopher Beaumont, was familiar with the administration and life in Punjab. Wanting to preserve the appearance of impartiality, Radcliffe also kept his distance from Viceroy Mountbatten.[3]

No amount of knowledge could produce a line that would completely avoid conflict; already, "sectarian riots in Punjab and Bengal dimmed hopes for a quick and dignified British withdrawal".[45] "Many of the seeds of postcolonial disorder in South Asia were sown much earlier, in a century and half of direct and indirect British control of large part of the region, but, as book after book has demonstrated, nothing in the complex tragedy of partition was inevitable."[46]

Haste and indifference

[edit]Radcliffe justified the casual division with the truism that no matter what he did, people would suffer. The thinking behind this justification may never be known since Radcliffe "destroyed all his papers before he left India".[47] He departed on Independence Day itself, before even the boundary awards were distributed. By his own admission, Radcliffe was heavily influenced by his lack of fitness for the Indian climate and his eagerness to depart India.[48]

The implementation was no less hasty than the process of drawing the border. On 16 August 1947 at 5:00 pm, the Indian and Pakistani representatives were given two hours to study copies, before the Radcliffe award was published on 17 August.[49]

Secrecy

[edit]To avoid disputes and delays, the division was done in secret. The final Awards were ready on 9 and 12 August, but not published until two days after the partition.

According to Read and Fisher, there is some circumstantial evidence that Nehru and Patel were secretly informed of the Punjab Award's contents on 9 or 10 August, either through Mountbatten or Radcliffe's Indian assistant secretary.[50] Regardless of how it transpired, the award was changed to put a salient portion of the non-Muslim majority Firozpur district (consisting of the two Muslim-majority tehsils of Firozpur and Zira) east of the Sutlej canal within India's domain instead of Pakistan's.[51][52] There were two apparent reasons for the switch: the area housed an army arms depot,[53] and contained the headwaters of a canal which irrigated the princely state of Bikaner, which would accede to India.[54][55][56]

Implementation

[edit]After the partition, the fledgling governments of India and Pakistan were left with all responsibility to implement the border. After visiting Lahore in August, Viceroy Mountbatten hastily arranged a Punjab Boundary Force to keep the peace around Lahore, but 50,000 men was not enough to prevent thousands of killings, 77% of which were in the rural areas. Given the size of the territory, the force amounted to less than one soldier per square mile. This was not enough to protect the cities much less the caravans of the hundreds of thousands of refugees who were fleeing their homes in what would become Pakistan.[57]

Both India and Pakistan were loath to violate the agreement by supporting the rebellions of villages drawn on the wrong side of the border, as this could prompt a loss of face on the international stage and require the British or the UN to intervene. Border conflicts led to three wars, in 1947, 1965, and 1971, and the Kargil conflict of 1999.

Disputes

[edit]There were disputes regarding the Radcliffe Line's award of the Chittagong Hill Tracts and the Gurdaspur district. Disputes also evolved around the districts of Malda, Khulna, and Murshidabad in Bengal and the sub-division of Karimganj of Assam.

In addition to Gurdaspur's Muslim majority tehsils, Radcliffe also gave the Muslim majority tehsils of Ajnala (Amritsar District), Zira, Firozpur (in Firozpur District), Nakodar and Jullandur (in Jullandur District) to India instead of Pakistan.[58] On the other hand, Chittagong Hill Tracts and Khulna, with non-Muslim population of 97% and 51% respectively, were awarded to Pakistan.

Punjab

[edit]Firozpur District

[edit]Indian historians now accept that Mountbatten probably did influence the Firozpur award in India's favour.[59] The headworks of River Beas, which later joins River Sutlej flowing into Pakistan, were located in Firozpur. Congress leader Nehru and Viceroy Mountbatten had lobbied Radcliffe that headworks should not go to Pakistan.[60]

Gurdaspur District

[edit]

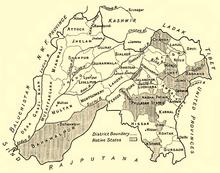

The Gurdaspur district was divided geographically by the Ravi River, with the Shakargarh tehsil on its west bank, and Pathankot, Gurdaspur and Batala tehsils on its east bank. The Shakargarh tehsil, the biggest in size, was awarded to Pakistan. (It was subsequently merged into the Narowal district of West Punjab.[62]) The three eastern tehsils were awarded to India. (Pathankot was eventually made a separate district in East Punjab.) The division of the district was followed by a population transfer between the two nations, with Muslims leaving for Pakistan and Hindus and Sikhs arriving from there.

The entire district of Gurdaspur had a bare majority of 50.2% Muslims.[63] (In the `notional' award attached to the Indian Independence Act, all of Gurdaspur district was marked as Pakistan with a 51.14% Muslim majority.[64] In the 1901 census, the population of Gurdaspur district was 49% Muslim, 40% Hindu, and 10% Sikh.[65]) The Pathankot tehsil was predominantly Hindu while the other three tehsils were Muslim majority.[66] In the event, only Shakargarh was awarded to Pakistan.

Radcliffe explained that the reason for deviating from the notional award in the case of Gurdaspur was that the headwaters of the canals that irrigated the Amritsar district lay in the Gurdaspur district and it was important to keep them under one administration.[64] Radcliffe might have sided with Lord Wavell's reasoning from February 1946 that Gurdaspur had to go with the Amritsar district, and the latter could not be in Pakistan due to its Sikh religious shrines.[64][67] In addition, the railway line from Amritsar to Pathankot passed through the Batala and Gurdaspur tehsils.[68] He further claimed that to compensate for the exclusion of the Gurdaspur district, they included the entire Dinajpur district in the eastern zone of Pakistan, which similarly had a marginal Muslim majority.

Pakistanis have alleged that the award of the three tehsils to India was a manipulation of the Award by Lord Mountbatten in an effort to provide a land route for India to Jammu and Kashmir.[63] However, Shereen Ilahi points out that the land route to Kashmir was entirely within the Hindu-majority Pathankot tehsil. The award of the Batala and Gurdaspur tehsils to India did not affect the Kashmir land route.[69]

Pakistani view on the award of Gurdaspur to India

[edit]Pakistan maintains that the Radcliffe Award was altered by Mountbatten; Gurdaspur was handed over to India and thus was manipulated the accession of Kashmir to India.[70] In support of this view, some scholars claim the award to India "had little to do with Sikh demands but had much more to do with providing India a road link to Jammu and Kashmir."[71]

As per the 'notional' award that had already been put into effect for purposes of administration ad interim, all of Gurdaspur district, owing to its Muslim majority, was assigned to Pakistan.[72] From 14 to 17 August, Mushtaq Ahmed Cheema acted as the Deputy Commissioner of the Gurdaspur District, but when, after a delay of two days, it was announced that the major portion of the district had been awarded to India instead of Pakistan, Cheema left for Pakistan.[73] The major part of Gurdaspur district, i.e. three of the four sub-districts had been handed over to India giving India practical land access to Kashmir.[74] It came as a great blow to Pakistan. Jinnah and other leaders of Pakistan, and particularly its officials, criticized the award as 'extremely unjust and unfair'.[75]

Muhammad Zafarullah Khan, who represented the Muslim League in July 1947 before the Radcliffe Boundary Commission, stated that the boundary commission was a farce. A secret deal between Mountbatten and Congress leaders had already been struck.[76] Mehr Chand Mahajan, one of the two non-Muslim members of the boundary commission, in his autobiography, has acknowledged that when he was selected for the boundary commission, he was not inclined to accept the invitation as he believed that the commission was just a farce and that decisions were actually to be taken by Mountbatten himself.[77] It was only under British pressure that the charges against Mountbatten of last minute alterations in the Radcliffe Award were not officially brought forward by Pakistani Government in the UN Security Council while presenting its case on Kashmir.[78]

Zafrullah Khan states that, in fact, adopting the tehsil as a unit would have given Pakistan the Firozepur and Zira tehsils of the Firozpur District, the Jullundur and Nakodar tehsils of Jullundur district and the Dasuya tehsil of the Hoshiarpur district. The line so drawn would also give Pakistan the princely state of Kapurthala[b] (which had a Muslim majority) and would enclose within Pakistan the whole of the Amritsar district of which only one tehsil, Ajnala, had a Muslim majority. It would also give Pakistan the Shakargarh, Batala and Gurdaspur tehsils of the Gurdaspur district. If the boundary went by Doabs, Pakistan could get not only the 16 districts which had already under the notional partition been put into West Punjab, including the Gurdaspur District, but also get the Kangra District in the mountains, which was about 93% Hindu and was located to the north and east of Gurdaspur. Or one could go by commissioners' divisions. Any of these units being adopted would have been more favourable to Pakistan than the present boundary line. The tehsil was the most favourable unit.[72] But all of the aforementioned Muslim majority tehsils, with the exception of Shakargarh, were handed over to India while Pakistan didn't receive any Non-Muslim majority district or tehsil in Punjab.[58] Zafruallh Khan states that Radcliffe used district, tehsil, thana, and even village boundaries to divide Punjab in such a way that the boundary line was drawn much to the prejudice of Pakistan.[72] However, while Muslims formed about 53% of the total population of Punjab in 1941, Pakistan received around 58% of the total area of the Punjab, including more of the most fertile parts.

According to Zafrullah Khan, the assertion that the award of the Batala and Gurdaspur tehsils to India did not 'affect' Kashmir is far-fetched. If Batala and Gurdaspur had gone to Pakistan, Pathankot tehsil would have been isolated and blocked. Even though it would have been possible for India to get access to Pathankot through the Hoshiarpur district, it would have taken quite long time to construct the roads, bridges and communications that would have been necessary for military movements.[74]

Assessments on the 'Controversial Award of Gurdaspur to India and the Kashmir Dispute'

[edit]Stanley Wolpert writes that Radcliffe in his initial maps awarded Gurdaspur district to Pakistan but one of Nehru's and Mountbatten's greatest concerns over the new Punjab border was to make sure that Gurdaspur would not go to Pakistan, since that would have deprived India of direct road access to Kashmir.[79] As per "The Different Aspects of Islamic Culture", a part of UNESCO's Histories flagship project, recently disclosed documents of the history of the partition reveal British complicity with the top Indian leadership to wrest Kashmir from Pakistan. Alastair Lamb, based on the study of recently declassified documents, has convincingly[citation needed] proven that Mountbatten, in league with Nehru, was instrumental in pressurizing Radcliffe to award the Muslim-majority district of Gurdaspur in East Punjab to India which could provide India with the only possible access to Kashmir.[80] Andrew Roberts believes that Mountbatten cheated over India-Pak frontier[81] and states that if gerrymandering took place in the case of Firozepur, it is not too hard to believe that Mountbatten also pressurized Radcliffe to ensure that Gurdaspur wound up in India to give India road access to Kashmir.[82][83][84]

Perry Anderson states that Mountbatten, who was officially supposed to neither exercise any influence on Radcliffe nor to have any knowledge of his findings, intervened behind the scenes – probably at Nehru's behest – to alter the award. He had little difficulty in getting Radcliffe to change his boundaries to allot the Muslim-majority district of Gurdaspur to India instead of Pakistan, thus giving India the only road access from Delhi to Kashmir.[85]

However, some British works suggest that the 'Kashmir State was not in anybody's mind'[86] when the Award was being drawn and that even the Pakistanis themselves had not realized the importance of Gurdaspur to Kashmir until the Indian forces actually entered Kashmir.[87] Both Mountbatten and Radcliffe, of course, have strongly denied those charges. It is impossible to accurately quantify the personal responsibility for the tragedy of Kashmir as the Mountbatten papers relating to the issue at the India Office Library and records are closed to scholars for an indefinite period.[88]

Bengal

[edit]Chittagong Hill Tracts

[edit]The Chittagong Hill Tracts had a majority non-Muslim population of 97% (most of them Buddhists), but was given to Pakistan. The Chittagong Hill Tracts People's Association (CHTPA) petitioned the Bengal Boundary Commission that, since the CHTs were inhabited largely by non-Muslims, they should remain within India. The Chittagong Hill Tracts was an excluded area since 1900 and was not part of Bengal. It had no representative at the Bengal Legislative Assembly in Calcutta, since it was not part of Bengal. Since they had no official representation, there was no official discussion on the matter, and many on the Indian side assumed the CHT would be awarded to India.[90][91]

On 15 August 1947, Chakma and other indigenous Buddhists celebrated independence day by hoisting Indian flag in Rangamati, the capital of Chittagong Hill Tracts. When the boundaries of Pakistan and India were announced by radio on 17 August 1947, they were shocked to know that the Chittagong Hill Tracts had been awarded to Pakistan. The Baluch Regiment of the Pakistani Army entered Chittagong Hill Tracts a week later and lowered the Indian flag at gun point.[92][93] The rationale of giving the Chittagong Hill Tracts to Pakistan[according to whom?] was that they were inaccessible to India and to provide a substantial rural buffer to support Chittagong (now in Bangladesh), a major city and port; advocates for Pakistan[which?] forcefully argued to the Bengal Boundary Commission that the only approach was through Chittagong.[citation needed]

The indigenous people sent a delegation led by Sneha Kumar Chakma to Delhi to seek help from the Indian leadership. Sneha Kumar Chakma contacted Sardar Patel by phone. Sardar Patel was willing to help, but insisted Sneha Kumar Chakma seek assistance from Prime Minister Pandit Nehru. But Nehru refused to help fearing that military conflict for Chittagong Hill Tracts might draw the British back to India.[91]

Malda District

[edit]Another disputed decision made by Radcliffe was the division of the Malda district of Bengal. The district overall had a slight Muslim majority,[94] but was divided and most of it, including Malda town, went to India. The district remained under East Pakistan administration for 3–4 days after 15 August 1947. It was only when the award was made public that the Pakistani flag was replaced by the Indian flag in Malda.[citation needed]

Khulna and Murshidabad Districts

[edit]The Khulna District (with a marginal Hindu majority of 51%) was given to East Pakistan in lieu of the Murshidabad district (with a 70% Muslim majority), which went to India. However, the Pakistani flag remained hoisted in Murshidabad for three days until it was replaced by the Indian flag on the afternoon of 17 August 1947.[95][96]

Karimganj

[edit]The Sylhet district of Assam joined Pakistan in accordance with a referendum.[97] However, the Karimganj sub-division (with a Muslim majority) was separated from Sylhet and given to India, where it became a district in 1983. As of the 2001 Indian census, Karimganj district now has a Muslim majority of 52.3%.[98]

Legacy

[edit]Legacy and historiography

[edit]As a part of a series on borders, the explanatory news site Vox featured an episode looking at "the ways that the Radcliffe line changed Punjab, and its everlasting effects" including disrupting "a centuries-old Sikh pilgrimage" and separating "Punjabi people of all faiths from each other."[99][100]

Artistic depictions

[edit]One notable depiction is Drawing the Line, written by British playwright Howard Brenton. On his motivation for writing the play, Brenton said he first became interested in the story of the Radcliffe Line while holidaying in India and hearing stories from people whose families had fled across the new line.[101] Defending his portrayal of Cyril Radcliffe as a man who struggled with his conscience, Brenton said, "There were clues that Radcliffe had a dark night of the soul in the bungalow: he refused to accept his fee, he did collect all the papers and draft maps, took them home to England and burnt them. And he refused to say a word, even to his family, about what happened. My playwright's brain went into overdrive when I discovered these details."[101]

Indian filmmaker Ram Madhvani created a nine-minute short film where he explored the plausible scenario of Radcliffe regretting the line he drew. The film was inspired by W. H. Auden's poem on the Partition.[102][103]

Visual artists Zarina Hashmi,[104] Salima Hashmi,[105] Nalini Malini,[106] Reena Saini Kallat[107] and Pritika Chowdhry[108] have created drawings, prints and sculptures depicting the Radcliffe Line.

See also

[edit]- India–Pakistan border

- Curzon line

- Indo-Bangladesh enclaves

- McMahon Line

- Durand Line

- Sykes-Picot Agreement

- Rajkahini

Notes

[edit]- ^ Schofield, Kashmir in Conflict (2003, p. 35): Wavell, however, had made a more significant political judgement in his plan, submitted to the secretary of state, Lord Pethick-Lawrence, in February 1946: 'Gurdaspur must go with Amritsar for geographical reasons and Amritsar being sacred city of Sikhs must stay out of Pakistan... Fact that much of Lahore district is irrigated from upper Bari Doab canal with headworks in Gurdaspur district is awkward but there is no solution that avoids all such difficulties.'

- ^ Princely States were given the option of either acceding to one of the two countries (India and Pakistan) or declaring independence. The ruler of Kapurthala acceded to India.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Read & Fisher, The Proudest Day 1998, p. 482

- ^ Smitha, Independence section, para. 7.

- ^ a b Read, Anthony; Fisher, David (1998). The Proudest Day: India's Long Road to Independence. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. p. 483. ISBN 9780393045949.

After briefly visiting Lahore and Calcutta to meet the members of the two commissions, Radcliffe settled into the Controller's House on the edge of the viceregal estate, avoiding contact with the viceroy as far as possible, to minimize any suspicions of influence and impropriety.

- ^ Tan & Kudaisya 2000, p. 162–163.

- ^ Ambedkar, Bhimrao Ramji (1941) [first published 1940], Thoughts on Pakistan, Bombay: Thacker and company

- ^ Sialkoti, Punjab Boundary Line Issue 2014, p. 73–76.

- ^ Dhulipala, Creating a New Medina 2015, pp. 124, 134, 142–144, 149: "Thoughts on Pakistan 'rocked Indian politics for a decade'."

- ^ Sialkoti, Punjab Boundary Line Issue 2014, p. 82.

- ^ Sialkoti, Punjab Boundary Line Issue 2014, p. 84–85.

- ^ Sarila, Narendra Singh (2006). "Wavell Plays the Great game". The Shadow of the Great Game : The Untold Story of India's Partition. New York: Caroll and Graf Publishers. p. 195. ISBN 9780786719129. Retrieved 17 March 2022.

- ^ Sialkoti, Punjab Boundary Line Issue 2014, p. 85–86.

- ^ Datta, The Punjab Boundary Commission Award 1998, p. 858.

- ^ Sialkoti, Punjab Boundary Line Issue 2014, p. 86.

- ^ Shaw, Jeffrey M.; Demy, Timothy J. (2017). War and Religion: An Encyclopedia of Faith and Conflict [3 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. p. 371. ISBN 9781610695176.

Upon the assurances of the Congress Party that Sikh interests would be respected as an independent India, Sikh leadership agreed to support the Congress Party and its vision of a united India rather than seeking a separate state. When Partition was announced by the British in 1946, Sikhs were considered a Hindu sect for Partition purposes. They violently opposed the creation of Pakistan since historically Sikh territories and cities were included in the new Muslim homeland.

- ^ Self and Sovereignty: Individual and Community in South Asian Islam Since 1850, Ayesha Jalal, pages 433-434

- ^ Kudaisya, Gyanesh; Yong, Tan Tai (2004). The Aftermath of Partition in South Asia. Routledge. p. 100. ISBN 978-1-134-44048-1.

No sooner was it made public than the Sikhs launched a virulent campaign against the Lahore Resolution. Pakistan was portrayed as a possible return to an unhappy past when Sikhs were persecuted and Muslims the persecutor. Public speeches by various Sikh political leaders on the subject of Pakistan invariably raised images of atrocities committed by Muslims on Sikhs and of the martyrdom of their gurus and heroes. Reactions to the Lahore Resolution were uniformly negative and Sikh leaders of all political persuasions made it clear that Pakistan would be 'wholeheartedly resisted'. The Shiromani Akali Dal, the party with a substantial following amongst the rural Sikhs, organized several well-attended conferences in Lahore to condemn the Muslim League. Master Tara Singh, leader of the Akali Dal, declared that his party would fight Pakistan 'tooth and nail'. Not be outdone, other Sikh political organizations, rival to the Akali Dal, namely the Central Khalsa Young Men Union and the moderate and loyalist Chief Khalsa Dewan, declared in equally strong language their unequivocal opposition to the Pakistan scheme.

- ^ War and Religion: An Encyclopedia of Faith and Conflict [3 Volumes], Jeffrey M Shaw, Timothy J Demmy, page 375

- ^ a b The Sikhs of the Punjab, Volumes 2-3, J S Grewal, page 176

- ^ a b Ethnic Group's of South Asia and the Pacific: An Encyclopedia, James Minahan, page 292

- ^ Sialkoti, Punjab Boundary Line Issue 2014, pp. 87–89.

- ^ Metcalf, Barbara D.; Metcalf, Thomas R. (2012), A Concise History of Modern India (Third ed.), Cambridge University Press, pp. 216–217, ISBN 978-1-139-53705-6, archived from the original on 30 July 2018, retrieved 29 July 2018: "... the Congress leadership, above all Jawaharlal Nehru, [...] increasingly came to the conclusion that, under the Cabinet mission proposals, the centre would be too weak to achieve the goals of the Congress ..."

- ^ Jalal, Ayesha (1994) [first published 1985], The Sole Spokesman: Jinnah, the Muslim League and the Demand for Pakistan, Cambridge University Press, pp. 209–210, ISBN 978-0-521-45850-4: "Just when Jinnah was beginning to turn in the direction that he both wanted and needed to go, his own followers pressed him to stick rigidly to his earlier unbending stance which he had adopted while he was preparing for the time of bargaining in earnest."

- ^ Sialkoti, Punjab Boundary Line Issue 2014, pp. 94–95.

- ^ Sialkoti, Punjab Boundary Line Issue 2014, pp. 95–96.

- ^ Fraser, T. G. (1984). Partition In Ireland India And Palestine: Theory And Practice. Palgrave Macmillan UK. p. 123. ISBN 978-1-349-17610-6. Archived from the original on 30 July 2018. Retrieved 7 May 2018.

- ^ Moore, Robin James. "Mountbatten, India, and the Commonwealth". Journal of Commonwealth & Comparative Politics. 19 (1): 4–53.

Though Mountbatten thought the concept of Pakistan 'sheer madness', he became reconciled to it in the course of six interviews with Jinnah from 5 to 10 April. Jinnah, whom he described as a 'psychopathic case', remained obdurate in the face of his insistence that Pakistan involved the partition of Bengal and the Punjab.

- ^ Sialkoti, Punjab Boundary Line Issue 2014, pp. 98–99.

- ^ Sialkoti, Punjab Boundary Line Issue 2014, pp. 97–98.

- ^ Sialkoti, Punjab Boundary Line Issue 2014, pp. 108–109.

- ^ a b c Frank Jacobs (3 July 2012). "Peacocks at Sunset". Opinionator: Borderlines. The New York Times. Archived from the original on 14 July 2012. Retrieved 15 July 2012.

- ^ Mansergy

- ^ Read & Fisher, The Proudest Day 1998, p. 483

- ^ Read & Fisher, The Proudest Day 1998, pp. 482–483

- ^ Read & Fisher, The Proudest Day 1998, p. 418: "He wrote to then Prime Minister Clement Attlee, 'It makes all the difference to me to know that you propose to make a statement in the House, terminating the British 'Raj' on a definite and specified date; or earlier than this date, if the Indian Parties can agree a constitution and form a Government before this.'"

- ^ "Minutes of the award meeting : Held on 16 August 1947". Archived from the original on 22 November 2014. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ^ a b Chester, Lucy (2009). Borders and Conflicts in South Asia: The Radcliffe Boundary Commission and the Partition of Punjab. Manchester: Manchester university Press. ISBN 9780719078996.

- ^ Read & Fisher, The Proudest Day 1998, p. 482: "After the obligatory wrangles, with Jinnah playing for time by suggesting calling in the United Nations, which could have delayed things for months if not years, it was decided to set up two boundary commissions, each with an independent chairman and four High Court judges, two nominated by Congress and two by the League."

- ^ Mishra, Exit Wounds 2007, para. 19: "Irrevocably enfeebled by the Second World War, the British belatedly realized that they had to leave the subcontinent, which had spiraled out of their control through the nineteen-forties. ... But in the British elections at the end of the war, the reactionaries unexpectedly lost to the Labour Party, and a new era in British politics began. As von Tunzelmann writes, 'By 1946, the subcontinent was a mess, with British civil and military officers desperate to leave, and a growing hostility to their presence among Indians.' ... The British could not now rely on brute force without imperiling their own sense of legitimacy. Besides, however much they 'preferred the illusion of imperial might to the admission of imperial failure,' as von Tunzelmann puts it, the country, deep in wartime debt, simply couldn't afford to hold on to its increasingly unstable empire. Imperial disengagement appeared not just inevitable but urgent."

- ^ Chester, The 1947 Partition 2002, "Boundary Commission Format and Procedure section", para. 5.

- ^ Read & Fisher, The Proudest Day 1998, 483, para. 1

- ^ population?

- ^ Read & Fisher, The Proudest Day 1998, p. 485

- ^ Read & Fisher, The Proudest Day 1998, pp. 484–485: "After the 3 June 1947 plan had been announced, the main Sikh organization, the Shiromani Akali Dal, had distributed a circular saying that 'Pakistan means total death to the Sikh Panth [community] and the Sikhs are determined on a free sovereign state with the [rivers] Chenab and the Jamna as its borders, and it calls on all Sikhs to fight for their ideal under the flag of the Dal.'"

- ^ Read & Fisher, The Proudest Day 1998, p. 481

- ^ Mishra, Exit Wounds 2007, para. 4

- ^ Mishra, Exit Wounds 2007, para. 5

- ^ Chester, The 1947 Partition 2002, "Methodology", para. 1.

- ^ Read & Fisher, The Proudest Day 1998, p. 484: Years later, he told Leonard Mosley, "The heat is so appalling, that at noon it looks like the blackest night and feels like the mouth of hell. After a few days of it, I seriously began to wonder whether I would come out of it alive. I have thought ever since that the greatest achievement which I made as Chairman of the Boundary Commission was a physical one, in surviving."

- ^ Read & Fisher, The Proudest Day 1998, p. .494

- ^ Read & Fisher, The Proudest Day 1998, p. 490

- ^ Singh, Kirpal (2006). "Introduction". Select Documents on Partition of Punjab - 1947: India and Pakistan: Punjab, Haryana and Himachal-India and Punjab-Pakistan. New Delhi: National Book Shop. pp. xxvi–xxvii. ISBN 9788171164455. Retrieved 4 April 2022.

- ^ French, Patrick (1998). Liberty or Death : India's Journey to Independence and Division. London: Flamingo. pp. 328–330. ISBN 9780006550457. Retrieved 4 April 2022.

- ^ Datta, Vishwa Nath (1998). "The Punjab Boundary Commission Award (12 August, 1947)". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 59: 860. JSTOR 44147058. Retrieved 4 April 2022 – via JSTOR.

It seems that Radcliffe had wanted to compensate Pakistan for having given a small portion of Lahore District and most of Gurdaspur to India, but he changed his mind. Firozpur was an important cantonment area, the major military bastion south of the Sutlej, and a junction point where four railway lines and three high ways met to cross the barrage-cum-bridge towards Kasur and Lahore. Perhaps geographical and strategic considerations weighed with Radcliffe.

- ^ Altaf, Muhammad (2021). "Colonial Hydraulic Infrastructure, Princely States, and the Partition of the Punjab" (PDF). Journal of the Punjab University Historical Society. 34 (2): 128–131.

- ^ Mansergh, Nicolas (1983). "The Maharaja of Bikaner to Rear-Admiral Viscount Mountbatten of Burma: Telegram (10 August 1947)". Constitutional Relations between Britain and India: The Transfer of Power 1942-7. Vol. XII. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. pp. 638, 645, 662. Retrieved 4 April 2022.

- ^ Sadullah, Mian Muhammad (1983). "Arguments of the Bikaner State". The Partition of the Punjab, 1947: A Compilation of Official Documents. Vol. 2. Lahore: National Documentation Centre. pp. 202–210. Retrieved 4 April 2022.

- ^ Read & Fisher, The Proudest Day 1998, pp. 487–488

- ^ a b Pervaiz I Cheema; Manuel Riemer (22 August 1990). Pakistan's Defence Policy 1947–58. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 27–. ISBN 978-1-349-20942-2. Archived from the original on 30 July 2018. Retrieved 29 June 2017.

- ^ Owen Bennett Jones (2003). Pakistan: Eye of the Storm. Yale University Press. pp. 60–. ISBN 978-0-300-10147-8. Archived from the original on 30 July 2018. Retrieved 29 June 2017.

- ^ Khan, Ansar Hussain (1999). "The Truth of the Partition of the Punjab in August 1947: Statement by Christopher Beaumont". The Rediscovery of India: A New Subcontinent. Orient Longman. p. 332. ISBN 9788125015956. Retrieved 8 April 2022.

- ^ Singh, Kirpal (2005). "Memorandum Submitted to the Punjab Boundary Commission by the Indian National Congress". Select Documents on Partition of Punjab - 1947: India and Pakistan: Punjab, Haryana and Himachal-India and Punjab-Pakistan. Delhi: National Book Shop. p. 212. ISBN 9788171164455. Retrieved 17 March 2022.

- ^ "Narowal – Punjab Portal". Archived from the original on 1 October 2011. Retrieved 28 June 2011.

- ^ a b Tan & Kudaisya 2000, p. 91.

- ^ a b c Schofield, Kashmir in Conflict 2003, p. 35.

- ^ "Gurdāspur District – Imperial Gazetteer of India, v. 12, p. 395". Archived from the original on 8 April 2008. Retrieved 25 April 2008.

- ^ Schofield, Kashmir in Conflict 2003, p. 38.

- ^ Ahmed, Pakistan: The Garrison State 2013, pp. 65–66: "The final border was almost a ditto copy of Viceroy Lord Wavell's top secret Demarcation Plan of February 1946, which was an auxiliary to the Demarcation Plan of February 1946...".

- ^ Schofield, Kashmir in Conflict 2003, pp. 33–34.

- ^ Ilahi, Shereen (2003). "The Radcliffe Boundary Commission and the Fate of Kashmir". India Review. 2 (1): 77–102. doi:10.1080/714002326. ISSN 1473-6489. S2CID 153890196.

- ^ Zaidi, Z. H. (2001), Pakistan Pangs of Birth, 15 August-30 September 1947, Quaid-i-Azam Papers Project, National Archives of Pakistan, pp. 378–379, ISBN 9789698156091, retrieved 17 March 2022

- ^ Ziring, Lawrence (1997), Pakistan in the Twentieth Century: A Political History, Karachi: Oxford University Press, p. 62, ISBN 978-0-19-577816-8

- ^ a b c The Reminiscences of Sir Muhammad Zafrulla Khan by Columbia University, 2004, p. 155, archived from the original on 30 July 2018, retrieved 20 July 2017

- ^ "Gurdaspur – the dist that almost went to Pak". The Tribune India. 15 August 2015. Archived from the original on 26 July 2017. Retrieved 21 July 2017.

- ^ a b The Reminiscences of Sir Muhammad Zafrulla Khan by Columbia University, 2004, p. 158, archived from the original on 30 July 2018, retrieved 20 July 2017

- ^ Zaidi, Z. H. (2001), Pakistan Pangs of Birth, 15 August-30 September 1947, Quaid-i-Azam Papers Project, National Archives of Pakistan, p. 380, ISBN 9789698156091, archived from the original on 28 July 2017, retrieved 20 July 2017,

The division of India is now finally and irrevocably effected. No doubt we feel that the carving out of this great independent Muslim State has suffered injustices. We have been squeezed in as much it was possible, and the latest blow that we have received was the award of the Boundary Commission. It is an unjust, incomprehensible and even perverse award.

- ^ Muhammad Zafarullah Khan, Tahdith-i-Ni'mat, Pakistan Printing Press, 1982, p. 515

- ^ Mehr Chand Mahajan, Looking Back: The Autobiography Bombay, 1963, p. 113, archived from the original on 30 July 2018, retrieved 21 July 2017

- ^ Sohail, Massarat (1991), Partition and Anglo-Pakistan relations, 1947–51, Vanguard, pp. 76–77, ISBN 9789694020570

- ^ Wolpert, Stanley (2009), Shameful Flight: The Last Years of the British Empire in India, Oxford University Press, USA, p. 167, ISBN 9780195393941, archived from the original on 25 September 2014, retrieved 18 September 2017

- ^ The Different Aspects of Islamic Culture (PDF), 2016, p. 355, archived (PDF) from the original on 11 August 2017, retrieved 9 May 2017

- ^ Author's Review, Eminent Churchillians

- ^ Andrew Roberts (16 December 2010). Eminent Churchillians. Orion. pp. 128–. ISBN 978-0-297-86527-8. Archived from the original on 30 July 2018. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- ^ Robert, Andrew (1994), Eminent Chruchillians, archived from the original on 22 January 2011, retrieved 16 May 2007

- ^ Sher Muhammad Garewal, "Mountbatten and Kashmir Issue", Journal of Research Society of Pakistan, XXXIV (April 1997), pp.9–10

- ^ Anderson, Perry (19 July 2012), "Why Partition?", London Review of Books, 34 (14), archived from the original on 21 July 2017, retrieved 20 July 2017

- ^ Hodson, H. V. (1969), The Great Divide: Britain, India, Pakistan, London: Hutchinson, p. 355, ISBN 9780090971503

- ^ Tinker, Hugh (August 1977), "Pressure, Persuasion, Decision: Factors in the Partition of the Punjab, August 1947", Journal of Asian Studies, XXXVI (4): 701, doi:10.2307/2054436, JSTOR 2054436, S2CID 162322698

- ^ Robert, Andrew (1994), Eminent Churchillians, p. 105

- ^ Porter, A. E. (1933). "Census of India, 1931. Vol. V: Bengal and Sikkim. Part II: Tables" (PDF). Linguistic Survey of India. Calcutta: Central Publication Branch, Government of India. pp. 220–223. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- ^ Khisha, Mukur K. (1996). All That Glisters. Minerva Press. p. 49. ISBN 978-1861060525.

- ^ a b Chakma, Dipak Kumar, ed. (February 2013). The Partition and the Chakmas and Other Writings of Sneha Kumar Chakma. India: D. K. Chakma (Pothi.com). p. 42. ISBN 978-9351049272.

- ^ Talukdar, S. P. (1994). Chakmas: An Embattled Tribe. India: Uppal Publishing House. p. 64. ISBN 978-818-556-5507.

- ^ Balibar, Etienne. "Is there a "Neo-Racism"?". Calcutta Research group. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 5 September 2007.

- ^ Dutch, R. A. (1942). Census of India, 1941: Volume 4, Bengal (Tables) (Reports). Vol. 4. Simla: Government of India Press. pp. 24–25. JSTOR saoa.crl.28215987. OCLC 316711026. Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- ^ "Nawabs' Murshidabad House lies in tatters". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 5 January 2017. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- ^ "Hindus & Muslims embrace each other as brothers". Amrita Bazaar Patrika. Dhaka. 19 August 1947. p. 5. Retrieved 15 January 2023.

As per announcement of June 3 last Murshidabad has been placed in Eastern Pakistan Dominion. People of Berhampore to-day celebrated Independence Day in the absence of any decision made by the Boundary Commission by saluting the Pakistan State Flag.

- ^ "Sylhet (Assam) to join East Pakistan". Keesing's Record of World Events. July 1947. p. 8722. Archived from the original on 4 December 2013. Retrieved 2 June 2014.

- ^ ORGI. "Census of India Website : Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India". Archived from the original on 14 May 2007.

- ^ Johnny Harris and Christina Thornell (26 June 2019). "How a border transformed a subcontinent: This line divided India and Pakistan". Retrieved 26 July 2019.

A brief history of how the region was split in two.

- ^ Ranjani Chakraborty, Danush Parvaneh, and Christina Thornell (22 March 2019). "How the British failed India and Pakistan: The history of two neighbors born at war — and the British strategy behind it". Vox.

The two nations were born at war — which can be traced back to this British strategy.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Web Chat with Howard Brenton". TheGuardian.com. 14 January 2014. Archived from the original on 1 July 2014. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- ^ "This Bloody Line". YouTube. 18 March 2017. Archived from the original on 30 July 2018.

- ^ "Watch: This Bloody Line, Ram Madhvani's short film on India-Pak divide". 18 March 2017. Archived from the original on 3 August 2017. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- ^ "Zehra Jumabhoy on the art of Zarina". www.artforum.com. September 2019. Retrieved 15 June 2022.

- ^ "Zones of Dreams | Art UK". artuk.org. Retrieved 15 June 2022.

- ^ "Omar Kholeif on curating for Abu Dhabi Art". The National. 31 July 2017. Retrieved 15 June 2022.

- ^ Anzi, Achia (1 June 2021). "The ambivalence of borders: Map art through the lens of North-East Indian artists". Jindal Global Law Review. 12 (1): 117–137. doi:10.1007/s41020-021-00142-9. ISSN 2364-4869. S2CID 237916446.

- ^ "75 Years Post-Partition: Artist Pritika Chowdhry on her Partition Anti-Memorial Project | COSAS". southernasia.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 15 June 2022.

Sources

[edit]- Ahmed, Ishtiaq (2013), Pakistan – The Garrison State: Origins, Evolution, Consequences (1947-2011), Oxford University Press Pakistan, ISBN 978-0-19-906636-0

- Chester, Lucy (February 2002), "The 1947 Partition: Drawing the Indo-Pakistani Boundary", American Diplomacy, archived from the original on 28 June 2011, retrieved 22 January 2007

- Datta, V. N. (2002), "Lord Mountbatten and the Punjab Boundary Commission Award", in S. Settar; Indira B. Gupta (eds.), Pangs of Partition: The parting of ways, Manohar, pp. 13–39, ISBN 978-81-7304-306-2

- Dhulipala, Venkat (2015), Creating a New Medina, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-107-05212-3

- Mansergh, Nicholas, ed. The Transfer of Power, 1942-7. (12 volumes)[full citation needed]

- Mishra, Pankaj (13 August 2007). "Exit Wounds". The New Yorker.

- Read, Anthony; Fisher, David (1998), The Proudest Day: India's Long Road to Independence, New York: W. W. Norton & Company, ISBN 9780393045949

- Schofield, Victoria (2003) [First published in 2000], Kashmir in Conflict, London and New York: I. B. Taurus & Co, ISBN 978-1860648984

- Sialkoti, Zulfiqar Ali (2014), "An Analytical Study of the Punjab Boundary Line Issue during the Last Two Decades of the British Raj until the Declaration of 3 June 1947" (PDF), Pakistan Journal of History and Culture, XXXV (2)

- Tan, Tai Yong; Kudaisya, Gyanesh (2000), The Aftermath of Partition in South Asia, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-134-44048-1

Further reading

[edit]- India: Volume XI: The Mountbatten Viceroyalty-Announcement and Reception of 3 June Plan, 31 May-7 July 1947. Reviewed by Wood, J.R. "Dividing the Jewel: Mountbatten and the Transfer of Power to India and Pakistan". Pacific Affairs, Vol. 58, No. 4 (Winter, 1985–1986), pp. 653–662. JSTOR

- Berg, E., and van Houtum, H. Routing borders between territories, discourses, and practices (p.128).

- Chester, Lucy P. Borders and Conflict in South Asia: The Radcliffe Boundary Commission and the Partition of Punjab. Manchester UP, 2009.

- Collins, L., and Lapierre, D. (1975) Freedom at Midnight.

- Collins, L., and Lapierre, D. Mountbatten and the Partition of India. Delhi: Vikas Publishing House, 1983.

- Heward, E. The Great and the Good: A Life of Lord Radcliffe. Chichester: Barry Rose Publishers, 1994.

- Mishra, Pankaj (13 August 2007). "Exit Wounds". The New Yorker.

- Moon, P. The Transfer of Power, 1942-7: Constitutional Relations Between Britain and India: Volume X: The Mountbatten Viceroyalty-Formulation of a Plan, 22 March-30 May 1947. Review "Dividing the Jewel" at JSTOR

- Moon, Blake, D., and Ashton, S. The Transfer of Power, 1942-7: Constitutional Relations Between Britain and India: Volume XI: The Mountbatten Viceroyalty Announcement and Reception of the 3rd June Plan 31 May- 7 July 1947. Review "Dividing the Jewel" at JSTOR

- Smitha, F. The US and Britain in Asia, to 1960. MacroHistory website, 2001.

- Tunzelmann, A. Indian Summer. Henry Holt.

- Wolpert, S. (1989). A New History of India, 3rd ed. New York: Oxford University Press.

External links

[edit]- Drawing the Indo-Pakistani border Archived 28 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine