Propaganda in the United States

In the United States, propaganda is spread by both government and non-government entities. Throughout its history, to the present day, the United States government has issued various forms of propaganda to both domestic and international audiences. The US government has instituted various domestic propaganda bans throughout its history, however, some commentators question the extent to which these bans are respected.[1]

In Manufacturing Consent published in 1988, Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky argue that the mass communication media of the U.S. "are effective and powerful ideological institutions that carry out a system-supportive propaganda function, by reliance on market forces, internalized assumptions, and self-censorship, and without overt coercion".[2] Some academics have argued that Americans are more susceptible to propaganda due to the culture of advertising.[3]

Domestic

[edit]Politico noted the ineffectiveness of domestic propaganda bans. "Officials get around the restriction on publicity agents by giving public relations staff such titles as “health communications specialist” or they outsource the spinmeister work to private communications firms. During an effort to cut back on PR in the administration of Harry Truman, the Air Force even classified some public affairs officers as chaplains."[1]

World War I

[edit]The first large-scale use of propaganda by the U.S. government came during World War I. The government enlisted the help of citizens; including children to help promote war bonds and stamps to help stimulate the economy. To keep the prices of war supplies down (steel, food, etc.), the U.S. government produced posters that encouraged people to reduce waste and grow their own vegetables in "victory gardens". The public skepticism that was generated by the heavy-handed tactics of the Committee on Public Information would lead the postwar government to officially abandon the use of propaganda.[4]

The 1915 film The German Side of the War was compiled from footage filmed by Chicago Tribune cameraman Edwin F. Weigle. It was one of the only American films to show the German perspective of the war.[5] At the theater lines stretched around the block; the screenings were received with such enthusiasm that would-be moviegoers resorted to purchasing tickets from scalpers.[6]

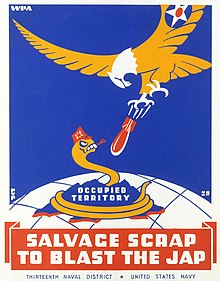

World War II

[edit]During World War II, the United States officially had no propaganda, but the Roosevelt government used means to circumvent this official line. One such propaganda tool was the publicly owned but government-funded Writers' War Board (WWB). The activities of the WWB were so extensive that it has been called the "greatest propaganda machine in history".[4] Why We Fight is a famous series of US government propaganda films made to justify US involvement in World War II. Response to the use of propaganda in the United States was mixed, as attempts by the government to release propaganda during World War I was negatively perceived by the American public.[7] The government did not initially use propaganda but was ultimately persuaded by businesses and media, which saw its use as informational.[8][better source needed] Cultural and racial stereotypes were used in World War II propaganda to encourage the perception of the Japanese people and government as a "ruthless and animalistic enemy that needed to be defeated", leading to many Americans seeing all Japanese people in a negative light.[9] Many people of Japanese ancestry, most of whom were American citizens,[10][11] were forcibly rounded up and placed in internment camps in the early 1940s.

From 1944 to 1948, prominent US policy makers promoted a domestic propaganda campaign aimed at convincing the U.S. public to agree to a harsh peace for the German people, for example by removing the common view of the German people and the Nazi Party as separate entities.[12] The core of this campaign was the Writers' War Board, which was closely associated with the Roosevelt administration.[12]

Another means was the United States Office of War Information that Roosevelt established in June 1942, whose mandate was to promote understanding of the war policies under the director Elmer Davis. It dealt with posters, press, movies, exhibitions, and produced often slanted material conforming to US wartime purposes.[13]

Cold War

[edit]Propaganda during the Cold War was at its peak in the early years, during the 1950s and 1960s.[14] The United States would make propaganda that criticized and belittled the enemy, the Soviet Union. The American government dispersed propaganda through movies, television, music, literature and art. The United States officials did not call it propaganda, maintaining they were portraying accurate information about Russia and their Communist way of life during the 1950s and 1960s.[15] The United States boycotted the 1980 Olympics held in Moscow along with Japan and West Germany, among many other nations. When the Olympics were held in Los Angeles in 1984, the Soviets retaliated by not showing up for the games. In terms of education, American propaganda took the form of videos children watched in school; one such video is called How to Spot a Communist.[16]

Operation Mockingbird

[edit]Operation Mockingbird was an alleged large-scale program of the United States Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) that began in the early years of the Cold War and attempted to manipulate domestic American news media organizations for propaganda purposes. According to author Deborah Davis, Operation Mockingbird recruited leading American journalists into a propaganda network and influenced the operations of front groups. CIA support of front groups was exposed when an April 1967 Ramparts article reported that the National Student Association received funding from the CIA.[17] In 1975, Church Committee Congressional investigations revealed Agency connections with journalists and civic groups.

War on Drugs

[edit]

There has been an abundant amount of propaganda in the half-century-long "war on drugs" that began under President Richard M. Nixon in June 1971, when he initiated the first federally funded programs aimed at drug prevention in the U.S. The 1960s had seen the rise of a rebellious youth movement that popularized drug use. With many citizens using marijuana and other drugs, and many soldiers returning from Vietnam with heroin habits, there was widespread drug use in the U.S.[18] One tactic of Nixon's initiative, still used today, was a national anti-drug media campaign aimed at youths. The government used posters and advertisements to scare children and teenagers into avoiding drug use.[19]

Between 1971 and 2011, the U.S. spent more than $2.5 trillion fighting the war on drugs. Nixon also dramatically increased the presence of federal drug control agencies, and pushed through measures such as mandatory sentencing and no-knock warrants.[19] The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) was created during his second term in 1973 to tackle both domestic drug use and the smuggling of illegal narcotics into America. The D.A.R.E. program began in 1983 (during the Reagan administration) and dovetailed with Nancy Reagan's campaign to educate children to "Just Say No" to drugs. The messaging permeated popular culture and was promoted by broadcasters through such venues as scripted television sitcoms and family programs, in effect to have fiction help influence reality. By 2003, the D.A.R.E. program had cost $230 million and involved 50,000 police officers, but never showed promising results in reducing illegal drug use.[20]

The National Youth Anti-Drug Media Campaign, originally established by the National Narcotics Leadership Act of 1988,[21][22] is a domestic propaganda campaign designed to "influence the attitudes of the public and the news media with respect to drug abuse" with a related goal of "reducing and preventing drug abuse among young people in the United States".[23] Now conducted by the Office of National Drug Control Policy under the Drug-Free Media Campaign Act of 1998,[24][25] the media campaign cooperates with the Partnership for a Drug-Free America and other government and non-government organizations.[26]

Gulf War

[edit]Shortly after Iraq's invasion of Kuwait in 1990, the organization Citizens for a Free Kuwait was formed in the US. It hired the public relations firm Hill & Knowlton for about $11 million, paid by Kuwait's government.[27]

Among many other means of influencing US opinion, such as distributing books on Iraqi atrocities to US soldiers deployed in the region, "Free Kuwait" T-shirts and speakers to college campuses, and dozens of video news releases to television stations, the firm arranged for an appearance before a group of members of the US Congress in which a young woman identifying herself as a nurse working in the Kuwait City hospital described Iraqi soldiers pulling babies out of incubators and letting them die on the floor.[28]

The story helped tip both the public and Congress towards a war with Iraq: six Congressmen said the testimony was enough for them to support military action against Iraq and seven Senators referenced the testimony in debate. The Senate supported the military actions in a 52–47 vote. However, a year after the war, this allegation was revealed to be a fabrication. The young woman who had testified was found to be a member of Kuwait's Royal Family and the daughter of Kuwait's ambassador to the US.[28] She had not lived in Kuwait during the Iraqi invasion.

Iraq War

[edit]In early 2002, the U.S. Department of Defense launched an information operation, colloquially referred to as the Pentagon military analyst program.[29] The goal of the operation is "to spread the administrations's talking points on Iraq by briefing retired commanders for network and cable television appearances," where they have been presented as independent analysts.[30] On 22 May 2008, after this program was revealed in The New York Times, the House passed an amendment that would make permanent a domestic propaganda ban that until now has been enacted annually in the military authorization bill.[31]

The Shared Values Initiative was a public relations campaign that was intended to sell a "new" America to Muslims around the world by showing that American Muslims were living happily and freely, without persecution, in post-9/11 America.[32] Funded by the United States Department of State, the campaign created a public relations front group known as the Council of American Muslims for Understanding (CAMU). The campaign was divided in phases; the first of which consisted of five mini-documentaries for television, radio, and print with shared values messages for key Muslim countries.[33]

Ad Council

[edit]The Ad Council, an American non-profit organization that distributes public service announcements on behalf of various private and federal government agency sponsors, has been labeled as "little more than a domestic propaganda arm of the federal government"[by whom?] given the Ad Council's historically close collaboration with the President of the United States and the federal government.[34] According to the Ad Council official website they aim to make sure advertisements are not as biased and do not harm any individuals.[35] They have a myriad of published press releases and news articles relaying around different topics in the United States.[36]

Smith-Mundt Modernization Act

[edit]In 2013, the Smith-Mundt Act, colloquially known as the "anti-propaganda law"[37] was amended.[38] The amendment repealed the Smith-Mundt's act ban on disseminating "information and material about the United States intended primarily for foreign audiences".[38][37]

Some advocates of repealing the anti-propaganda law did so in the name of "transparency", an approach that The Atlantic called "a remarkably creative spin".[39] Michael Hastings suggested that the Smith-Mundt Modernization Act would open the door to the dissemination of Pentagon propaganda to domestic audiences,[37] while a Pentagon official told Hastings that "senior public affairs" officers in the Department of Defense sought to "get rid" of Smith-Mundt because it restricts methods used to cultivate support for unpopular policies, such as the Iraq and Afghanistan wars.[40]

COVID-19 pandemic

[edit]In April 2020, President Donald Trump and the United States government played a campaign video for the Republican Party, which was widely regarded as a propaganda video.[41][42][43] This video referred to a timeline of the U.S. government's response to the pandemic, only displaying favorable moments. Some commentators and analysts believed that this was to protect President Donald Trump and his government's reputation, especially before the country's 2020 presidential election. Supporters[who?] maintained this was to combat widespread media criticism stating that he failed to act quickly enough to stop the spread of COVID-19.

ChinaAngVirus disinformation campaign

[edit]According to a report by Reuters, the United States ran a disinformation campaign in the Philippines, later expanded to Central Asia and the Middle East, from 2020 to 2021.[44][45] It sought to discredit China, in particular its Sinovac vaccine. The campaign was overseen by Special Operations Command Pacific as well as the United States Central Command. Military personnel at MacDill Air Force Base in Florida operated phony social media accounts, some of which were more than five years old according to Reuters. During the COVID-19 pandemic, they disseminated hashtags of #ChinaIsTheVirus and posts claiming that the Sinovac vaccine contained gelatin from pork and therefore was haram or forbidden for purposes of Islamic law. US diplomats aware of the campaign were against the idea, but they were overruled by the military, which also asked tech companies not to take down the content after it was discovered by Facebook and Twitter. A retrospective review by the DoD subsequently uncovered other social and political messaging that was "many leagues away" from acceptable military objective. The primary contractor for the U.S. military on the project was General Dynamics IT, which received $493 million for its role. The campaign reportedly aimed to counter "China’s COVID diplomacy."[44] A Pentagon spokesperson noted to Reuters that China had started a "disinformation campaign to falsely blame the United States for the spread of COVID-19."[44]

International

[edit]Through several international broadcasting operations, the US disseminates American cultural information, official positions on international affairs, and daily summaries of international news. These operations fall under the International Broadcasting Bureau, the successor of the United States Information Agency, established in 1953 (which had a 2 billion dollar per year budget). IBB's operations include Voice of America, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, Alhurra and other programs. They broadcast mainly to countries where the United States finds that information about international events is limited, either due to poor infrastructure or government censorship. The Smith-Mundt Act prohibits the Voice of America from disseminating information to US citizens that were produced specifically for a foreign audience.

During the Cold War, the United States ran covert propaganda campaigns in countries that appeared likely to become Soviet satellites, such as Italy, Afghanistan, and Chile.[46] According to the Church Committee report, US agencies ran a "massive propaganda campaign" on Chile, where over 700 news items placed in American and European media resulted from CIA activities in a six-weeks period alone.[47]

In 2006, The Pentagon announced the creation of a new unit aimed at spreading propaganda about supposedly "inaccurate" stories being spread about the Iraq War. These "inaccuracies" have been blamed on the enemy trying to decrease support for the war. Donald Rumsfeld has been quoted as saying these stories are something that keeps him up at night.[48]

Psychological operations

[edit]

The US military defines psychological operations, or PSYOP, as:

planned operations to convey selected information and indicators to foreign audiences to influence the emotions, motives, objective reasoning, and ultimately the behavior of foreign governments, organizations, groups, and individuals.[49]

Some argue that the Smith-Mundt Act, adopted in 1948, explicitly forbids information and psychological operations aimed at the US public.[50] However, Emma Briant points out that this is a common confusion: the Smith-Mundt Act only ever applied to the State Department, not the Department of Defense and military PSYOP, which are governed by Title 10 of the US Code.[51][52][53] Nevertheless, the current easy access to news and information from around the globe, makes it difficult to guarantee PSYOP programs do not reach the US public. Or, in the words of Army Col. James A. Treadwell, who commanded the U.S. military psyops unit in Iraq in 2003, in The Washington Post:

There's always going to be a certain amount of bleed-over with the global information environment.[54]

Agence France Presse reported on U.S. propaganda campaigns that:

The Pentagon acknowledged in a newly declassified document that the US public is increasingly exposed to propaganda disseminated overseas in psychological operations. But the document suggests that the Pentagon believes the US law that prohibits exposing the public to propaganda does not apply to the unintended blowback from such operations.[55]

Former US Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld approved the document referred to, which is titled "Information Operations Roadmap."[53][55] The document acknowledges restrictions on targeting domestic audience, but fails to offer any way of limiting the effect PSYOP programs have on domestic audiences.[50][52][56] A recent book by Emma L. Briant brings this up to date, detailing the big changes in practice following 9/11 and especially after the Iraq War as US defense adapted to a more fluid media environment and brought in new internet policies.[57]

Several incidents in 2003 were documented by Sam Gardiner, a retired Air Force colonel, which he saw as information-warfare campaigns that were intended for "foreign populations and the American public." Truth from These Podia,[58] as the treatise was called, reported that the way the Iraq War was fought resembled a political campaign, stressing the message instead of the truth.[53]

Social media

[edit]In 2011, The Guardian reported that the United States Central Command (Centcom) was working with HBGary to develop software that would allow the US government to "secretly manipulate social media sites by using fake online personas to influence internet conversations and spread pro-American propaganda." A Centcom spokesman stated that the "interventions" were not targeting any US-based web sites, in English or any other language, and also said that the propaganda campaigns were not targeting Facebook or Twitter.[59][60]

In October 2018, The Daily Telegraph reported that Facebook "banned hundreds of pages and accounts which it says were fraudulently flooding its site with partisan political content – although they came from the US instead of being associated with Russia."[61]

In 2022, the Stanford Internet Observatory and Graphika studied banned accounts on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and five other social media platforms that used deceptive tactics to promote pro-Western narratives.[62][63][64][65][66][67][68] Vice News noted that "U.S. leaning social media influence campaigns are, ultimately, very similar to those run by adversarial countries.",[62] while EuroNews quoted Stanford researcher Shelby Grossman as saying "I was shocked that the tactics we saw being used were identical to the tactics used by authoritarian regimes".[63] Meta claimed that "individuals associated with the U.S. military" were connected to the propaganda campaign.[69]

In October 2022, The Intercept reported that the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) was engaged in "broadening" efforts to counter speech that it considered "dangerous". Geoff Hale, the director of the Election Security Initiative at CISA, recommended the use of third-party information-sharing nonprofits as a “clearing house for information to avoid the appearance of government propaganda.”[70]

The Intercept reported in December 2022 that the United States military ran a "network of social media accounts and online personas", and that Twitter whitelisted a batch of accounts upon the request of the United States government. Whitelisting the propaganda accounts gave them the same privileges of a user with a blue check to increase the reach of their operations.[71][72]

See also

[edit]- Black propaganda

- Capitalist propaganda

- CIA influence on public opinion

- Fake news websites in the United States

- Mainstream media

- Media bias in the United States

- Military–entertainment complex

- Military–industrial–media complex

- Operation Earnest Voice

- Operation Mockingbird

- Propaganda of the Spanish–American War

- Propaganda through media

- Shared values initiative

- White propaganda

External links

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Call It What It Is: Propaganda". Politico. October 8, 2020. Retrieved November 7, 2023.

- ^ Herman, Edward S.; Chomsky, Noam. Manufacturing Consent. New York: Pantheon Books. p. 306.

- ^ Newitz, Annalee (June 4, 2024). "Chapter 3". Stories Are Weapons: Psychological Warfare and the American Mind. W. W. Norton & Company.

- ^ a b Thomas Howell, The Writers' War Board: U.S. Domestic Propaganda in World War II, Historian, Volume 59 Issue 4, pp. 795–813

- ^ Ward, Larry Ward (1981). The Motion Picture Goes to War: A Political History of the U.S. Government's Film Effort in the World War, 1914-1918. University of Iowa.

- ^ Isenberg, Michael (1973). War on Film: The American Cinema and World War I, 1914-1941. University of Colorado.

- ^ "Librarian of Congress Names 25 More Films to National Film Registry". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved February 2, 2024.

- ^ Riddle, Lincoln (August 6, 2016). "American Propaganda in World War II". warhistoryonline.com. Archived from the original on October 2, 2018. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- ^ Miles, Hannah (2012). "WWII Propaganda: The Influence of Racism". Artifacts (6). Archived from the original on December 1, 2019. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- ^ Semiannual Report of the War Relocation Authority, for the period January 1 to June 30, 1946, not dated. Papers of Dillon S. Myer. Scanned image at Archived 2018-06-16 at the Wayback Machine trumanlibrary.org. Retrieved 2006-09-18.

- ^ "The War Relocation Authority and The Incarceration of Japanese Americans During World War II: 1948 Chronology," Web page Archived 2018-06-16 at the Wayback Machine at www.trumanlibrary.org. Retrieved 2006-09-11.

- ^ a b Casey, Steven (2005). "The Campaign to Sell a Harsh Peace for Germany to the American Public, 1944-1948" (PDF). History. 90 (297): 62–92. doi:10.1111/j.1468-229X.2005.00323.x.

- ^ Little, Becky (December 19, 2016). "Inside America's Shocking WWII Propaganda Machine". National Geographic. Archived from the original on August 17, 2018. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- ^ "Cold War Propaganda". Alpha History. March 12, 2013. Archived from the original on January 8, 2021. Retrieved August 1, 2020.

- ^ "Cold War propaganda: the truth belonged to no one country – Melissa Feinberg | Aeon Essays". Aeon. Archived from the original on January 8, 2021. Retrieved February 26, 2019.

- ^ "Cold War propaganda". The Cold War. March 12, 2013. Archived from the original on January 8, 2021. Retrieved February 26, 2019.

- ^ Onis, Juan de (February 16, 1967). "Ramparts Says C.I.A. Received Student Report; Magazine Declares Agency Turned Group It Financed Into an 'Arm of Policy'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ "The United States War on Drugs". web.stanford.edu. Archived from the original on January 6, 2019. Retrieved February 18, 2019.

- ^ a b "A Brief History of the Drug War". Drug Policy Alliance. Archived from the original on August 5, 2019. Retrieved February 18, 2019.

- ^ "War on Drugs - History and Facts". www.criminaljusticeprograms.com. Archived from the original on January 8, 2021. Retrieved February 18, 2019.

- ^ National Narcotics Leadership Act of 1988 of the Anti–Drug Abuse Act of 1988, Pub. L. 100–690, 102 Stat. 4181, enacted November 18, 1988

- ^ Gamboa, Anthony H. (January 4, 2005), B-303495, Office of National Drug Control Policy — Video News Release (PDF), Government Accountability Office, footnote 6, page 3, archived (PDF) from the original on March 26, 2011, retrieved July 15, 2013

- ^ Gamboa, Anthony H. (January 4, 2005), B-303495, Office of National Drug Control Policy — Video News Release (PDF), Government Accountability Office, pp. 9–10, archived (PDF) from the original on March 26, 2011, retrieved July 15, 2013

- ^ Drug-Free Media Campaign Act of 1998 (Omnibus Consolidated and Emergency Supplemental Appropriations Act, 1999), Pub. L. 105–277 (text) (PDF), 112 Stat. 268, enacted October 21, 1998

- ^ Drug-Free Media Campaign Act of 1998 of the Omnibus Consolidated and Emergency Supplemental Appropriations Act, 1999, Pub. L. 105–277 (text) (PDF), 112 Stat. 268, enacted October 21, 1998

- ^ Office of National Drug Control Policy Reauthorization Act of 2006, Pub. L. 109–469 (text) (PDF), 120 Stat. 3501, enacted December 29, 2006, codified at 21 U.S.C. § 1708

- ^ "How PR Sold the War in the Persian Gulf | Center for Media and Democracy". Prwatch.org. October 28, 2004. Retrieved February 1, 2011.

- ^ a b Rowse, Ted (1992). "Kuwaitgate – killing of Kuwaiti babies by Iraqi soldiers exaggerated". Washington Monthly. Archived from the original on May 29, 2012. Retrieved June 20, 2021.

- ^ Barstow, David (April 20, 2008). "Message Machine: Behind Analysts, the Pentagon's Hidden Hand". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 8, 2021. Retrieved February 23, 2017.

- ^ Sessions, David (April 20, 2008). "Onward T.V. Soldiers: The New York Times exposes a multi-armed Pentagon message machine". Slate. Archived from the original on January 8, 2021. Retrieved May 14, 2008.

- ^ Barstow, David (May 24, 2008). "2 Inquiries Set on Pentagon Publicity Effort". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 8, 2021. Retrieved February 23, 2017.

- ^ Rampton, Sheldon (October 17, 2007). "Shared Values Revisited". Center for Media and Democracy. Archived from the original on December 2, 2019. Retrieved July 15, 2013.

- ^ "U.S. Reaches Out to Muslim World with Shared Values Initiative". America.gov. January 16, 2003. Archived from the original on October 18, 2011.

- ^ Barnhart, Megan (2009). "Selling the International Control of Atomic Energy: The Scientists Movement, the Advertising Council, and the Problem of the Public". In Mariner, Rosemary B.; Piehler, G. Kurt (eds.). The Atomic Bomb and American Society: New Perspectives. University of Tennessee Press. p. 106. ISBN 978-1-57233-648-3. Archived from the original on December 21, 2016. Retrieved December 11, 2016.

- ^ "Ad Council". AdCouncil. 2018. Archived from the original on January 8, 2021. Retrieved September 27, 2018.

- ^ "Press Releases". AdCouncil. 2018. Archived from the original on January 8, 2021. Retrieved September 27, 2018.

- ^ a b c "U.S. Repeals Propaganda Ban, Spreads Government-Made News to Americans". Foreign Policy. July 14, 2013. Retrieved November 6, 2023.

- ^ a b "H.R. 5736 To amend the United States Information and Educational Exchange Act of 1948 to authorize the domestic dissemination of information and material about the United States intended primarily for foreign audiences, and for other purposes" (PDF), 112th United States Congress, May 10, 2012, retrieved November 6, 2023

- ^ "Americans Finally Have Access to American Propaganda". The Atlantic. July 15, 2013. Retrieved November 7, 2023.

- ^ "Congressmen Seek To Lift Propaganda Ban". Buzzfeed. May 18, 2012. Retrieved November 7, 2023.

- ^ Analysis by Brian Stelter (April 14, 2020). "Propaganda on full display at Trump's latest coronavirus task force briefing". CNN. Archived from the original on October 9, 2020. Retrieved October 15, 2020.

- ^ C-SPAN, Source (April 14, 2020). "The coronavirus 'propaganda' video Trump played to media". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on January 8, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2020.

- ^ Blake, Aaron (April 14, 2020). "Trump's propaganda-laden, off-the-rails coronavirus briefing". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 8, 2020. Retrieved October 15, 2020.

- ^ a b c Bing, Chris; Schechtman, Joel (June 14, 2024). "Pentagon Ran Secret Anti-Vax Campaign to Undermine China during Pandemic". Reuters.

- ^ Toropin, Konstantin (June 14, 2024). "Pentagon Stands by Secret Anti-Vaccination Disinformation Campaign in Philippines After Reuters Report". Military.com. Archived from the original on June 14, 2024. Retrieved June 19, 2024.

- ^ "Church Committee Report, Volume VII - Hearings on Covert Action" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on January 8, 2021. Retrieved August 21, 2018.

- ^ "page 169, III. Major Covert Action Programs and Their Effects, Church Committee Report, Volume VII - Covert Action" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on January 8, 2021. Retrieved August 21, 2018.

- ^ "Pentagon boosts 'media war' unit". October 31, 2006. Archived from the original on January 8, 2021. Retrieved October 31, 2006 – via news.bbc.co.uk.

- ^ "Doctrine for Joint Psychological Operations Joint Publication 3-53" (PDF). September 5, 2003.

- ^ a b "Rumsfeld's Roadmap to Propaganda". nsarchive2.gwu.edu. Archived from the original on October 7, 2016. Retrieved March 13, 2019.

- ^ Briant, Emma L (2015) Propaganda and Counter-terrorism: Strategies for Global Change, Manchester: Manchester University Press: 41

- ^ a b Christopher J. Lamb. "Operations as a core competency" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 24, 2006.

- ^ a b c "CJR May/June 2006 - Mind Games". March 30, 2008. Archived from the original on March 30, 2008.

- ^ Military Plays Up Role of Zarqawi - Jordanian Painted As Foreign Threat To Iraq's Stability Archived 2021-01-08 at the Wayback Machine By Thomas E. Ricks, The Washington Post, April 10, 2006

- ^ a b US Propaganda Aimed at Foreigners Reaches US Public: Pentagon Document Archived 2007-06-13 at the Wayback Machine by Agence France Presse, January 27, 2006

- ^ US plans to 'fight the net' revealed Archived 2021-01-08 at the Wayback Machine By Adam Brookes, BBC, January 27, 2006

- ^ Briant, Emma L (2015) Propaganda and Counter-terrorism: Strategies for Global Change, Manchester: Manchester University Press

- ^ "National Security Archive - 30+ Years of Freedom of Information Action". nsarchive.gwu.edu. Archived from the original on January 8, 2021. Retrieved March 13, 2019.

- ^ "Revealed: US spy operation that manipulates social media". The Guardian. March 17, 2011. Retrieved November 6, 2023.

- ^ "Army of fake social media friends to promote propaganda". Computer World. February 22, 2011. Retrieved November 7, 2023.

- ^ "Facebook: Most political trolls are American, not Russian". The Daily Telegraph. October 12, 2018.

- ^ a b "Facebook and Twitter Take Down a U.S. Propaganda Operation Targeting Russia, China, and Iran". Vice News. August 24, 2022. Retrieved November 6, 2023.

- ^ a b "Researchers discover sprawling pro-U.S. social media influence campaign". NBC News. August 24, 2022. Retrieved November 6, 2023.

- ^ "First major covert pro-US propaganda campaign taken down by social media giants". EuroNews. September 1, 2022. Retrieved November 6, 2023.

- ^ "Researchers caught a pro-US campaign spreading propaganda on social media". The Verge. August 25, 2022. Retrieved November 6, 2023.

- ^ "Facebook, Twitter and Others Remove Pro-U.S. Influence Campaign". The New York Times. August 24, 2022. Retrieved November 6, 2023.

- ^ "Twitter and Meta take down pro-US propaganda campaign". BBC. August 26, 2022. Retrieved November 6, 2023.

- ^ "Pro-American Propaganda on Social Media Had Little Impact—Just Like Russian Propaganda on Social Media". Reason. September 1, 2022. Retrieved November 7, 2023.

- ^ "Meta claims US military link to online propaganda campaign". BBC. November 23, 2022. Retrieved November 8, 2023.

- ^ "Truth Cops: Leaked Documents Outline DHS's Plans to Police Disinformation". The Intercept. October 31, 2022. Retrieved November 7, 2023.

- ^ "Twitter aided the Pentagon in its covert online propaganda campaign". The Intercept. December 20, 2022. Retrieved November 5, 2023.

- ^ "Twitter secretly boosted psyops in Middle East, report says". Al Jazeera. December 21, 2022.