Project Gaia

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Project Gaia is a U.S.-based non-governmental, non-profit organization engaged in developing alcohol-based fuel markets for household use in Ethiopia and other developing countries.[1] The organization identifies alcohol fuels as a potential alternative to traditional cooking methods, which they suggest may contribute to fuel shortages, environmental issues, and public health concerns in these regions. Focusing on impoverished and marginalized communities, Project Gaia is active in Ethiopia, Nigeria, Brazil, Haiti, and Madagascar. The organization is also planning to expand its projects to additional countries.

Current cooking methods in energy poor communities: the problem

[edit]Biomass fuels and associated risks

[edit]

More than 3 billion people cook with wood fire worldwide. Approximately 60% of African families cook with traditional biomass, a percentage that increases to 90% for Sub-Saharan Africa.[1] Smoke and gaseous emissions pour out of burning wood, animal dung, or crop residues, leading to lung disease and respiratory illnesses in women and children. Traditional biomass fuels release emissions that contain pollutants dangerous to health, such as small particles, carbon monoxide (CO), nitrogen dioxide, butadiene, formaldehyde, and carcinogens such as benzopyrene and benzene. The World Health Organization estimates that more than 4 million people die each year from household air pollution generated by cooking with solid fuels in poorly ventilated spaces. 500,000 of these deaths are from childhood pneumonia.[2] Indoor air pollution is especially deadly for children; it is responsible for nearly 50% of pneumonia deaths in children under the age of five.[3]

Indoor air pollution

[edit]Because of their higher exposure to cook fires, women and children are particularly at risk. Indoor air pollution causes 56% of deaths and 80% of the global burden of disease for children under the age of five.[1] Indoor air pollution also increases the risk of acute lower respiratory infections, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and is associated with tuberculosis, perinatal mortality, low birth weight, asthma, otitis media, cancer of the upper airway, and cataracts. Respiratory disease is the leading cause of death for children.[4] Indoor air pollution disproportionately affects refugees and urban populations in poverty, due to crowded and poorly ventilated living areas, as well as those with a decrease immune response due to HIV/AIDS.[4]

Fuel collection

[edit]

Personal safety

[edit]Meanwhile, collecting wood involves risk to personal safety. Women and older children usually collect wood, often facing gender-based harassment and disputes with landowners who accuse them of trespassing. Women in Ethiopia's UNHCR refugee camps say that they fear assault, rape, and violence while searching for wood.[5]

Deforestation and desertification

[edit]Beyond these public health issues, cooking with wood fires is also unsustainable and contributes to rapid deforestation in the developing world. Where wood is already limited, its collection leads to desertification. In Africa, collection of wood for cooking and charcoal production is the primary reason for the disappearance of the forests.[6] Further, the burning of hydrocarbon fuels, coal, charcoal, and even dung contributes to the accumulation of greenhouse gases. Smoky cooking fires and stoves contribute to the soot that is estimated to cause approximately 16% of global warming.[7] Black carbon particles in the atmosphere are considered one of the most dangerous pollutants after carbon dioxide.[6] Furthermore, higher rates of deforestation and desertification force women to travel further and further to gather fuelwood, increasing their vulnerability to the dangers of fuelwood collection.[8]

Alternatives to biomass fuels

[edit]The available alternatives to biomass fuels do not offer much improvement. This was made in Central Africa for the benefit of locals and others. Kerosene is imported at significant expense, and is burnt with a wick stove that does not combust the fuel efficiently and tips or spills easily. The projected retail cost of ethanol is lower than that of government-subsidized kerosene in Ethiopia today.[4] Kerosene stoves are also prone to flare ups and explosions; accidental kerosene fires cause many injuries and deaths each year.[4] Kerosene releases carcinogenic emissions and is often poorly refined or adulterated by the time it is acquired for domestic use.[4] Liquified petroleum gas (LPG) burns cleanly but is expensive and cannot be produced locally. Charcoal, a processed biomass fuel, burns with less smoke, but emits carbon monoxide.[4] Meanwhile, coal produces all of the dangerous emissions of traditional biomass fuels and depending on its quality, also produces sulfur oxides and toxic elements such as arsenic, lead, fluorine, and mercury.[4]

Aid and energy

[edit]Aid initiatives and emergency response projects rarely provide energy for cooking, focusing instead on food rations and necessary cookware.[4] Occasionally the UNHCR purchases and provides biomass and transports it to communities where it is desperately needed. When aid projects do involve stoves, many undertake the dissemination of improved biomass stoves. These burn biomass fuel more efficiently but do not eliminate the household need for biomass nor eliminate indoor air pollution.[4]

The solution: alcohol fuels and clean cookstoves

[edit]

Alcohol fuels

[edit]Alcohol fuels have a low-flammability limit (LFL) that is higher than hydrocarbon fuels, which means they do not catch fire easily, even when spilled. They can be extinguished by water and are not prone to explosion like LPG (propane and butane). Alcohol burns cleanly, producing only carbon dioxide and water vapor, and none of the soot or toxic chemicals produced by solid fuels and kerosene. Alcohol fuels are clean, with particle emissions far below the WHO levels.[9] When used with an efficient stove, alcohol fuels can significantly improve indoor air quality, thereby improving respiratory health and the overall quality of life by reducing the global burden of disease." [10]

Alcohol is increasingly gaining recognition as a source of fuel. Because of initiatives like Project Gaia, the UNDP has placed the previously absent ethanol and methanol near the top of its “energy ladder,” a progression of fuels that range from dirty and inefficient (e.g. biomass) to clean and efficient (e.g. biogas, LPG, ethanol, methanol).[4] Project Gaia believes in gradual introduction of ethanol-burning appliances into both the private household market and the small or large institutional market, to ensure widespread acceptance.[4] As the alcohol fuel market increases, and acceptance of clean cookstoves grows, Project Gaia sees the potential for the use of other high-performing alcohol appliances that provide lighting, refrigeration and air-tempering, and generation.[4]

Ethanol

[edit]Ethanol can be produced locally from byproducts that would otherwise cause environmental damage. It can be produced from biomass, natural gas, coal, and even landfill gas—resources plentiful in many developing countries. The use of alcohol fuel for household fuel, therefore, is efficient resource management—transforming waste products to a highly valuable resource.[1] This transformation can lead to a cleaner environment, the forming of new jobs in industry, agriculture, manufacturing, and the service sector, and a decreased need for imported fuels.[1]

Clean cookstoves

[edit]The Clean Cook Stove

[edit]

Origins

[edit]Project Gaia's team currently works with the alcohol-based Clean Cook stove, a stable, stainless steel, one or two-burner stove adapted from the Origo stove invented by Bengt Ebbeson in 1979 and manufactured by Swedish company Domestic AB, the leading manufacturer of alcohol stoves and appliances worldwide. The Origo stove, recognized as the best alcohol stove available, is popular in the leisure markets in the U.S. and Europe, commonly for boating and camping use.[11] The stove's working life is to projected to be 5–10 years for daily use.[11] Project Gaia works to adapt the stove to local cooking needs and habits. Some of the adaptations made to the Clean Cook include the slight raising and redesign of the pot-stand to allow for larger pots and for more oxygen to reach the flame, and the addition of handles to make transport and refill of the stove easier.[11]

Domestic

[edit]Domestic seeks to address the developing world market because alcohol fuel technologies are particularly appropriate for it.[1] The Clean Cook contains a non-pressurized, no-spill fuel tank that can hold methanol or ethanol. The Clean Cook stove was designed with several specific safety measures. The Clean Cook stove's fuel canister holds an absorbent mineral fiber covered by a protective metal mesh, preventing fuel from spilling from the canister even when the stove is inverted.[11] The design of this fuel tank eliminates risk of explosion, flare-up, or leakage, and other safety features built into the stove make the CleanCook less likely to cause burns than other cooking methods.[1] Meanwhile, the Clean Cook is a high-performing stove, equivalent in power (1.5 to 2kW) and temperature to an LPG stove.[4]

Operation of the Stove

[edit]To operate the stove, its fuel canister must be filled with one liter of ethanol. If pouring the fuel results in drops around the hole, these must be wiped away. The canister must be clipped onto the base of the stove, the regulator opened, and the ethanol vapor lit with a match or lighter. After cooking, the canister should be left in position to limit further evaporation of remaining ethanol.[11]

Emissions vs. performance

[edit]The US-based Aprovecho Research Center has conducted tests comparing the emissions and energy performance of the CleanCook in comparison with conventional LPG and kerosene stoves.[11] When compared with kerosene, the CleanCook used less energy, produced lower emissions, and was quicker than to bring water to a boil. Compared with LPG, the CleanCook produced the same level of particulate emissions, but LPG released lower emissions of CO and was quicker to boil water.[11] The UNDP in Malawi compared the CleanCook with wood and charcoal stoves and found that the CleanCook cut wood stoves’ CO emission in half, particulate emission by 99%, and energy use by 71%. The findings in comparison with charcoal showed similar results, with the energy use decreased by 55% and the emission and particulate reduction even greater than for wood stoves.[11]

Local production and sustainability

[edit]Project Gaia believes that sustainable business is the best way to accomplish the goal of providing clean and safe cooking technology, and is supported by the UNDP Growing Sustainable Business (GSB) in its initiatives to bring the private and public sectors together.[4] Project Gaia's business model involves the merging of stove manufacture and sale with fuel production and sale, thereby giving consumers confidence that they will receive fuel after purchasing stoves, and also allowing part of the stoves’ costs to transfer to the fuel.[4] This financing mechanism is the model used for mobile phones and airtime – the initial cost of the stove would be cheaper to ensure its affordability, and this discount would be recovered over the course of several years in a very small mark-up in fuel cost.[4] Another benefit of this system is that it allows for ownership of the right to produce the stove or parts of the stove in Ethiopia. The CleanCook is currently manufactured in Slovakia, but the possibility of local production in Ethiopia is currently being explored.[4] Local production is in its early stages in Addis Ababa, with a starting goal of 18,000 stoves to be produced yearly.[11] Project Gaia's business goals also include certification through the CDM Gold Standard for dissemination of CleanCook stoves and promotion of alcohol fuels.[4]

Impact through education

[edit]

Education about indoor air pollution is a fundamental element of Project Gaia's mission, which it has pursued by spreading awareness about the impact of IAP through workshops, seminars, media coverage, and engagement with local, state, and federal government, and organizations such as the WHO in Ethiopia, and the FDRE’s Ministry of Health. The danger of IAP and its effects on populations is often neglected, with malaria, HIV/AIDS, and infectious diseases receiving the majority of attention.[citation needed]

Project Gaia is also working to educate the public about alcohol fuels and their potential for use in the developing world, and specifically, in the context of household energy.[4] The market for families throughout the developing world that could benefit from the use of alcohol fuels for cooking and household energy is in the range of 600 million.[4] As stated by the UNDP World Energy Assessment (2000), supplying modern energy services to the two billion people who still cook with traditional solid fuels and lack access to electricity is one of the most pressing problems facing humanity today.[12]

Projects by country

[edit]Ethiopia

[edit]

The Gaia Association

[edit]The Ethiopian counterpart of Project Gaia, Inc. is the Ethiopian non-governmental organization, the Gaia Association, which is a UNHCR implementing partner. Ethiopia possesses all of the necessary factors for successful technology transfer of alcohol fuel: the quantity of ethanol produced by its sugar industry, the fact that it depends on imported petroleum fuels and biomass, and its need for improved fuels and safer stoves.[13] In 2009, Ethiopia was producing approximately 8 million liters of ethanol annually.[6] Molasses and other byproducts of the industry were being dumped in Ethiopia's rivers until about a decade ago when one of Ethiopia's five mills, Finchaa Sugar Company, solved the waste problem by acquiring a distillery and producing ethanol.[11] Gaia answered an early query that Fincha Sugar opened, proposing a household energy market for the ethanol, as no gasoline blending or export market was being successfully developed.[4][6] Ethiopia's other mills have also become interested in producing ethanol, as a way to balance the fluctuations of sugar pricing.[4] Ethiopia's government is developing plans to build ethanol-producing distilleries at all sugar mills, creating an ethanol supply that could fuel over 200,000 stoves.[11]

Gaia is now planning to build its own micro distillery in Ethiopia as a demonstration project for what can be achieved with small and micro scale distillation plants. Gaia is working with the Ethiopian Environmental Protection authority, the Ministry of Mines and Energy and the Ministry of Agriculture to build this distillery. A range of feedstocks are being considered, including more conventional feedstocks such as molasses, and sugar cane or sweet sorghum juice, or unconventional feedstocks such as fruit waste from the markets in Addis Ababa or sugary materials from plants growing wild such as cactus, the bean pods from the mesquite tree (Prosopis), a noxious invasive species in Ethiopia, or the Giant Milkweed plant (Calotropis procera). Gaia is hoping to encourage very small scale distilleries owned by farmer groups or co-ops and small to medium-sized local entrepreneurs.[11][14]

Fuel blending

[edit]The domestic fuel blending market and the export market for ethanol remain difficult in Ethiopia for several reasons.[4] The technical precision and regulation necessary for successful blending has prevented its success in Ethiopia; major petroleum sellers like Shell, Total, Mobil, and domestic companies such as National Oil resist the blending of ethanol in petroleum fuels because the fuel supply system is poorly regulated and the fuel is sometimes adulterated.[4] Fuel sellers cannot trust the integrity of their fuel if blended with ethanol, because the ethanol may take up water into the fuel and promote phase separation and worsened contamination.[4] As for the export market, Ethiopia's ethanol production is too small to attract large international buyers and has only succeeded in selling ethanol at lower prices than other exporters.[4] Ethiopia's landlocked location also makes export difficult. The local selling of Finchaa's ethanol, therefore, provides a sustainable opportunity for Ethiopia, with prices that are affordable but also competitive with the potential export market.[4]

Deforestation

[edit]Ethiopia is energy-poor and 95-98% deforested, although most of its population still depends on biomass fuels.[6] Before beginning its pilot studies, Gaia found that refugee families use approximately 3.7 tons of fuel wood a year, and spend up to eight hours every two or three days collecting this wood.[11]

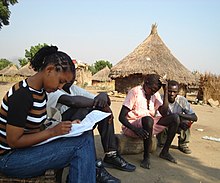

Pilot testing and stove placement

[edit]CleanCook stoves have now been tested in and placed in three UNHCR refugee camps, HIV/AIDS orphanages run by Mother Teresa's Missionaries of Charity, in a rural village in Ethiopia's Somali State, and in lower and middle-income private homes in Addis Ababa. Pilot studies conducted by the Gaia Association have yielded positive results and acceptance and widespread approval among households both in the refugee camps and in Addis Ababa. Project Gaia is also working to bring stove manufacturing to Addis Ababa by linking the Ethiopian business Makobu Enterprises PLC and Dometic AB, and encouraging government support for the designation of ethanol for household fuel purposes.[4]

Refugee camps in Ethiopia

[edit]Environmental impact

[edit]Refugee camps in Eastern Ethiopia that house refugees of Somali conflict have placed heavy pressure on the environment and resources of Ethiopia for the past two decades, reaching a combined population of 600,000 refugees in the early 1990s. The UNHCR and its partner NGOs supply these camps with basic needs but have not provided cooking fuel until recently. Fuel wood gathering, the responsibility of refugee women, has resulted in the almost complete deforestation of the regions around the refugee camps, and Ethiopia's government has banned all cutting of live trees around the camps.[11] The UNHCR must provide alternatives to wood fuel at any new refugee camps.

Active projects

[edit]Project Gaia is currently active in Awbarre refugee camp (formerly known as Teferi Ber) and Kebribeyah refugee camp, where all of the camp's approximately 1780 families have CleanCook stoves and a daily ration of ethanol, funded cooperatively by the UNHCR and the Gaia Association. The combined population of Kebribeyah and Awbarre camps is approximately 27,000 people, and the UNHCR is planning to re-open at least two more camps to make room for past refugees who have fled to Ethiopia again after returning to Somalia and experiencing worsening conditions since July 2007.[11]

In 2012, Gaia Association received a grant from the Nordic Climate Fund (NCF) to demonstrate the feasibility of locally produced ethanol for cooking. The grant provided funds to build a community owned and operated ethanol microdistillery. The distillery, which is currently under construction in the Kolfe-Keranio community on the outskirts of Addis Ababa, will be run by a local women's cooperative, the Former Women Fuelwood Carriers Association.

Also in 2012, in an effort to address the environmental and social problems associated with the overreliance on traditional biomass for household cooking, Gaia Association, together with the Ethiopian Environmental Protection Authority, is piloting a project to demonstrate small-scale, community owned and driven ethanol production from sugarcane (in the form of ethanol microdistilleries) in Amhara, Oromya & Gambella regional states. Partial installation of the EMDs has been completed in two of the three regional states.

Partnerships

[edit]Project Gaia works in collaboration with many organizations that help support pilot studies, encourage government involvement, and provide local or regional support. Gaia's lead business partners are members of the United Nations Global Compact, and many members of the Gaia team have joined the Partners for Clean Indoor Air (PCIA),[15] which developed out of the 2002 World Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD) in Johannesburg with the goal of cleaning up indoor air.[4] Project Gaia is also a member of the HEDON Household Energy Network which unites key actors and stakeholders in the movement for a cleaner, more efficient, and affordable household energy sector.[citation needed]

In Ethiopia, Gaia has created partnerships with organizations that serve poor communities and refugee camps. Gaia's Ethiopia partners include the UNHCR-RLO and the UNDP, the Good Shepherd Sisters, the Missionaries of Charity, the Former Women Fuelwood Carriers’ Association, Finchaa Sugar Company, the Ethiopian Rural Energy Development and Promotion Center, and the Ogaden Welfare and Development Association. Under its Breathe Easy Program, the Shell Foundation is a technical and a funding partner for Gaia's Ethiopia and Brazil projects. These partners have supported Gaia's pilot studies and helped to strengthen the relationships between Ethiopian businesses and European and American businesses, with the goal of facilitating the sustainable transfer of technology, goods, and services to Ethiopia.[4]

Nigeria

[edit]

By 2050 Nigeria is expected to outgrow the population of the US.[16] The market for cookstoves- and more importantly, cooking fuels- is huge. Spurring both ethanol and methanol production will create local jobs, help give farmers new markets, and be locally sourced.

Nigeria, like Ethiopia has high potential for large-scale ethanol production from starchy cassava and sugarcane molasses.[6] Nigeria also possesses an excess of natural gas in the form of gas flares; it is responsible for 40% of worldwide flaring. This natural gas can be easily converted to methanol and Nigeria's flared gas alone could fuel CleanCook stoves in every household in West Africa. Nigeria, like other West African countries, is energy poor and depends on fuelwood for cooking. In Nigeria, Project Gaia depends on the local support of the Centre of Household Energy and Health, based in the Niger Delta. Gaia's main sponsor in Delta State is the U.S. EPA in partnership with the Delta State Government.[4]

Gaia's technical partner for Nigeria, HydroChem, which is part of the Linde Group, is the leading provider of small-scale hydrogen, CO, and CO2 plants. These plants are easily adapted to manufacture methanol, by converting natural gas into liquid form, and thereby creating a fuel that can be used in the household energy market. In gas or electric form, it is not feasible for the developing world market because of the investment, infrastructure, and maintenance necessary and subsidies that are required to make it affordable.[4] HydroChem's plants are ideal for local, small-scale production at low expense in countries like Nigeria, where gas flares could be converted into household fuel.

Currently, Project Gaia is working with local commercial partners to begin a 10,000 stove pilot study.

Brazil

[edit]Project Gaia studied the acceptance of the CleanCook ethanol stove in different urban and rural households in the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil between 2006 and 2007. Because LPG was too costly for low-income families, most households in the study had been using firewood for cooking. In some areas, woodfuel collection is banned. Participating families could get fuel for cooking easily and cheaply at the gas pump. Households found ethanol easy, safe and affordable to use. The ability to buy ethanol in small quantities, rather than being forced to purchase large canisters of LPG, was most beneficial to low-income households.[citation needed]

Brazil's strong social policies have helped to lift families out of poverty and increase access to energy. As Brazil develops, Project Gaia is working to replicate the Brazilian model in other project sites. Project Gaia's work continues in partnership with Prolenha.

Madagascar

[edit]

Project Gaia began work in Madagascar beginning in 2008 at the request of the Government of Madagascar. Project Gaia's work is commissioned with the objective of multifaceted contribution to the goals of the Africa Action Plan (AAP) and the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and to the goals of several initiatives related to the development of alternative household energy sources. Gaia's work with household or indoor air pollution will address other MDGs such as the promotion of gender equality, improving maternal health, and ensuring environmental sustainability. The Madagascar Action Plan (MAP) is one initiative that is working to promote alternative sources of energy that will decrease the burden on Madagascar's forests and to reduce child mortality, a large factor of which is the household use of solid fuels.[17] Project Gaia's involvement also contributes to goals in several specific sectors including those of the Ministère de l’Environnement, des Eaux et Forêts et du Tourisme, the Ministère de l’Energie et des Mines, the Ministère de la Santé, du Planning Familial et de la Protection, the Ministère de l’Agriculture, Elevage et la Pêche, and the Foundation Tany Meva - piloting community-based use of ethanol for household cooking.

Haiti

[edit]Project Gaia launched operations in Haiti, in response to the increased need for relief after the 2010 hurricane and in the hopes of contribution to the “Build Back Better” strategy being developed by Haiti's government and other engaged nations and organizations. That Haiti is more than 98% deforested makes transition away from wood fuels essential, especially since 70% of Haiti's population continues to rely on charcoal and firewood for fuel. Since the earthquake, Haitian families have been spending at least 40% of their income on charcoal and all fuel prices have surged.[18]

Meanwhile, Haiti has great potential for local, sustainable production of ethanol because of its past status as a significant sugar cane producer and the capacity for revival of this industry. One million tons of sugar cane is produced annually – a decrease from 3 million in 1987 – and sugar mills and distilleries are already in place.[18] Ethanol, even before it is produced locally, can still be sold locally for a lower price than Haitian charcoal.[citation needed]

For this project, Gaia is receiving donations of ethanol fuel for CleanCook stoves from the Brazilian government and the Brazilian ethanol industry. Gaia's approach in Haiti involves three phases: 1) small-scale emergency intervention through donation of 500–5000 stoves, and work with local mills and distilleries to scale up domestic production of ethanol 2) larger-scale scale-up of 20,000–50,000 stoves and ethanol to IDP camps and large communities, partnership with other organizations and 3) sustainability work and local development, cooperation with government to encourage the passage of a biofuels plan, assessment of the state of local mills and distilleries that are closed, and of the possibility for micro distillery.[18]

Gaia's collaborators for its Haiti Project include the Government of Haiti Ministry of Women's Affairs, Government of Brazil Ministry of External Relations, UNICA, COSAN, Dometic Group, Viva Rio Haiti, Marin Biological Lab (Woods Hole), CODEP, Terra Endeavors, Inc., J&J Import, BDP International, Trees Water People, Public-Private Alliance Foundation (PPAF).

Pilot studies and financial sustainability

[edit]

Gaia Association conducted thorough pilot studies on the use of different household fuels in Addis Ababa, their varying prices, and the rates of their consumption. In 2004, Gaia began testing two-burner prototype stoves in 850 homes. Before and after the 850 stoves were placed, Gaia's field staff conducted household energy audits, consumer satisfaction studies and fuel price elasticity studies. In 50 homes, Gaia monitored IAP, recording levels of CO and particulate matter.[4] Approximately 150 of the stoves that were tested in Addis Ababa were placed in very low-income homes. This part of the study helped Gaia determine the ideal price level for ethanol so that it would be affordable to the average household and also reach the poorer households.[citation needed]

Pilot studies and business model

[edit]Throughout the process of pilot studies in each of its project sites, Gaia's team documented progress and compiled reports that charted the study results. Project Gaia used the study results to develop its business plan and to answer questions such as: Who is interested in the stove? Who can produce it? How should it be adapted to better suit its use? Who can distribute it? Who can supply the fuel? How will stove and fuel be linked?[4]

Simulation of future market conditions and local purchasing power

[edit]To simulate reality and ensure affordability of the stove, Gaia charged for ethanol during the Pilot studies. After a month of free fuel, during which families could get used to cooking with the stove, each household paid for its fuel, allowing fuel use and rationing to be accurately documented. After the first month of purchasing fuel, its price was increased to reflect the cost of ethanol once the local market is fully developed. Price Elasticity studies documented the impact of the price increase on the family and their capacity and willingness to pay. Pilot study data showed that these households demonstrated the necessary purchasing power to afford CleanCook stoves and their fuel, if the purchasing price of the stove was subsidized.[4]

Even the poorest urban communities pay for cooking fuels because they cannot gather their fuel, as many refugees do in rural areas of Ethiopia. Wood and charcoal prices have risen because of the need to travel further and further outside of the city to gather them. Poor families are often forced to pay more for fuel because they buy small quantities of low-quality fuel when they can afford to – sometimes before each meal. Even the lowest grade of fuel is often expensive when purchased this way.[4]

Government subsidization of petroleum-based fuels and long-term financial impact

[edit]Domestically produced ethanol would not require as much subsidization as petroleum-based fuels like kerosene because it can be sold for a lower price. Its domestic production, meanwhile, benefits the economy, and the subsidy that is contributed for its purchase does not leave the country as it does for imported fuel.[4]

In the context of the refugee camps, ethanol was not sold because of the lack of purchasing power among refugees. When fuel gathering exhausts the little remaining biomass, energy provisions will have to be donor-supplied. Providing stoves and improved fuel, however, can save long-term costs by increasing productivity and well-being among refugees, increasing industry, and reducing health care costs.[4]

Response to the stoves was very positive, both in households where families had experience with modern stoves and improved fuels, and in households without previous experience. The dominant response included appreciation for the cleanliness and safety of the stove and fuel and a positive evaluation of the stove's power and efficiency. In the refugee camps, CleanCook stoves allowed more women to cook inside their homes, and diminished the need for fuel wood gathering and allowed women more time to pursue income-generating activities, take care of personal health, provide childcare, and seek education. A reduced amount of fuel wood gathering also eased tensions between refugees and local landowners who do not welcome the gathering of wood from their land.[4][6]

Many groups supported Gaia in its pilot studies, including the UNHCR management and logistical staff for the refugee camps, by the Refugee Care Netherlands (ZOA) staff and FDRE Administration for Refugee and Returnee Affairs (ARRA) staff, field survey staff from the Ethiopian Rural Energy Development and Promotion Center, an Ethiopian government agency under the Ministry of Mines and Energy, the UNDP Growing Sustainable Businesses Program, Winrock International's Clean Energy Group, Makobu Enterprises management personnel, Dometic AB representatives from Research & Development, the Stove Division and Marketing, the Stokes Consulting Group, UNDP-GSB consultants, Finchaa Sugar, consultants from the Center for Entrepreneurship in International Health and Development at the University of California at Berkeley, and Shell Foundation advisors.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g "Impact of Improved Stoves and Fuels on IAP" Archived 2011-07-25 at the Wayback Machine, CEIHD Center for Entrepreneurship in International Health and Development. Retrieved 30 May 2010.

- ^ "DEFINE_ME_WA".

- ^ "WHO - Household air pollution and health".

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am "Removing Smoke from the Kitchen: An Alcohol Fueled Global Clean Cooking Initiative" Archived 2017-02-02 at the Wayback Machine, Changemakers.net, an initiative of Ashoka. Retrieved 30 May 2010.

- ^ Women's Refugee Commission. "Working Women At Risk: The Links Between Making a Living and Sexual Violence for Refugees in Ethiopia.". 27 August 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g Flannery-Allen, Julie. "Vital, Ethanol brings an energy revolution to households in the developing world". Retrieved 30 May 2010.

- ^ Institute for Governance and Sustainable Development (IGSD). "Reducing Black Carbon May Be the Fastest Strategy for Slowing Climate Change. IGSD/INECE Climate Briefing Note" Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ^ "Gaia Project". Capstone Games. Retrieved 2023-07-25.

- ^ World Health Organization "Pollution and Exposure Levels." Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ^ World Health Organization "Global Burden of Disease." Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o “Clean, safe ethanol stoves for refugee homes” Archived 2011-10-12 at the Wayback Machine, The Ashden Awards for sustainable energy. Retrieved 30 May 2010.

- ^ "World Energy Assessment: Energy and the Challenge of Sustainability" Archived 2007-06-09 at the Wayback Machine, UNDP. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ^ “Project Gaia Ethiopia” Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine, HEDON Household Energy Network. Retrieved 30 May 2010.

- ^ “African Renewable Energy Access Biomass Energy Initiative for Africa”[dead link], Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2018-11-23. Retrieved 2009-12-24.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "10 projections for the global population in 2050". Pew Research Center. 3 February 2014.

- ^ “Assessment of Ethanol as a Household Fuel”, Practical Action Consulting. Retrieved 30 May 2010.

- ^ a b c “Project Gaia & Haiti”, Project Gaia, Inc. Retrieved 30 May 2010.

Further reading

[edit]- "World Summit on Sustainable Development 2002 website". WSSD. Retrieved 4 June 2010.

- Women's Commission

- Heller, Lauren (September - October 2008). Working Women at Risk: The Links Between Making a Living and Sexual Violence for Refugees in Ethiopia. Women's Refugee Commission Field Mission to Ethiopia Report.

- Patrick, Erin (March 2006). Beyond Firewood: Fuel Alternatives and Protection Strategies for Displaced Women and Girls. Women's Commission for Refugee Women and Children.

- Sarkar, Siddhartha. Gender, Household Energy, and Empowerment

- World Health Organization (WHO)

- Rosenthal, Elisabeth (15 April 2009). "Third World Soot is Target in Climate Fight". New York Times.

- Shell Foundation

- Boiling Point, 2005

- The News Magazine of the International Union of Biological Sciences (IUBS)

- Journal of Peace Research

- LEISA MAGAZINE . SEPTEMBER 2003

- Nova Magazine