Prevention of autosomal recessive disorders

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2024) |

Prevention of autosomal recessive disorders is focused on making it less likely that two carriers for the same hereditary disease will have children together.

Background

[edit]

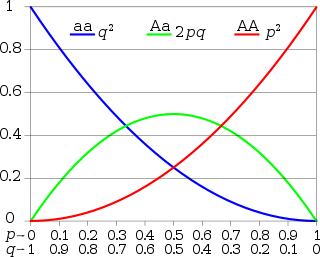

Some genetic disorders are caused by having two "bad" copies of a recessive allele. When the gene is located on an autosome (as opposed to a sex chromosome), it is possible for both men and women to be carriers. A child of two carriers has a 1/4 chance of being affected by the disorder.

Due to carriers being unaffected (or barely affected), the bad recessive alleles can persist in the gene pool for quite a while, even if the disorder is 100% lethal.[medical citation needed]

Outbreeding

[edit]Most modern societies have laws regarding incest,[1] with avoiding the genetic disorders caused by inbreeding as one of the major motivations.[2]

Both social acceptance and legality of first-cousin marriage is mixed. Some jurisdictions narrowly tailor their laws to preventing inbreeding: in Maine,[3] first cousins can marry with proof of genetic counseling, while in Arizona[4] and several other states, first cousins can marry if they are old or infertile.[5]

Carrier testing

[edit]Carrier testing can help guide the decisions of couples who are at high risk, e.g.:

- Both of Jewish descent – Several disorders including Tay–Sachs disease. The organization Dor Yeshorim offers testing in many countries.[citation needed]

- Both Cypriot – Thalassemia. Testing is fully subsidized and mandated in both jurisdictions on Cyprus.[6][failed verification]

- Both Maldivian – Thalassemia. Testing is fully subsidized and mandated in the Maldives.[7]

- Both from affected parts of Africa – Sickle-cell disease. Carrier testing is not widely available in many African countries[8] and disease burden remains high.

Couples who learn that they are both carriers may decide to part ways, adopt, or use preimplantation genetic diagnosis to select unaffected embryos.[citation needed]

Relation to eugenics

[edit]

These practices are not designed to change allele frequencies and therefore have little impact on future generations beyond the first. As a result, these practices are generally not considered to be a form of eugenics, despite overlapping goals.[9]

See also

[edit]- Disability-selective abortion – controversial alternative to prevention

References

[edit]- ^ Bittles, Alan Holland (2012). Consanguinity in Context. Cambridge University Press. pp. 178–187. ISBN 978-0521781862. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- ^ Wolf, Arthur P.; Durham, William H. (2004). Inbreeding, Incest, and the Incest Taboo: The State of Knowledge at the Turn of the Century. Stanford University Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-8047-5141-4.

- ^ "Title 19-A, §701: Prohibited marriages; exceptions".

- ^ https://codes.findlaw.com/az/title-25-marital-and-domestic-relations/az-rev-st-sect-25-101/

- ^ Frommer, Rachel (2021). "The Unconstitutionality of State Bans on Marriage Between First Cousins". Cardozo Law Review de Novo.

- ^ Cowan: "The last of my substantive chapters concentrates on the only two mandated premarital genetic screening programs in the world: both of them on the island of Cyprus, both of them focused on the recessive gene that, when it is doubled, causes b-thalassemia."

- ^ Waheed, Fazeela; Fisher, Colleen; Awofeso, AwoNiyi; Stanley, David (July 2016). "Carrier screening for beta-thalassemia in the Maldives: perceptions of parents of affected children who did not take part in screening and its consequences". Journal of Community Genetics. 7 (3): 243–253. doi:10.1007/s12687-016-0273-5. PMC 4960032. PMID 27393346.

- ^ Aneke, JohnC; Okocha, ChideE (2016). "Sickle cell disease genetic counseling and testing: A review". Archives of Medicine and Health Sciences. 4 (1): 50. doi:10.4103/2321-4848.183342.

- ^ Cowan, Ruth Schwartz (15 February 2009). "Moving up the slippery slope: Mandated genetic screening on Cyprus". American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C: Seminars in Medical Genetics. 151C (1): 95–103. doi:10.1002/ajmg.c.30202. PMID 19170092.