History of Tuvalu

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Tuvalu |

|---|

|

| People |

| Languages |

| Cuisine |

| Religion |

| Art |

| Music |

| Sport |

The first inhabitants of Tuvalu were Polynesians, so the origins of the people of Tuvalu can be traced to the spread of humans out of Southeast Asia, from Taiwan, via Melanesia and across the Pacific islands of Polynesia.

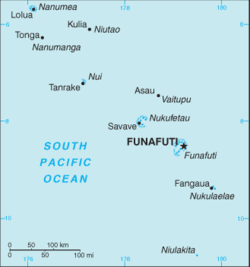

Various names were given to individual islands by the captains and chartmakers on visiting European ships. In 1819 the island of Funafuti, was named Ellice's Island; the name Ellice was applied to all nine islands, after the work of English hydrographer Alexander George Findlay.[1]

The United States claimed Funafuti, Nukufetau, Nukulaelae and Niulakita under the Guano Islands Act of 1856. This claim was renounced under the 1983 treaty of friendship between Tuvalu and the United States.[2]

The Ellice Islands came under Great Britain's sphere of influence in the late 19th century as the result of a treaty between Great Britain and Germany relating to the demarcation of the spheres of influence in the Pacific Ocean.[3] Each of the Ellice Islands was declared a British Protectorate[broken anchor] by Captain Herbert Gibson of HMS Curacoa, between 9 and 16 October 1892.[4] The Ellice Islands were administered as part of the British Western Pacific Territories (BWPT) as British protectorate by a Resident Commissioner from 1892 to 1916, and then as part of the Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony from 1916 to 1976.

In 1974, the Ellice Islanders voted for separate British dependency status as Tuvalu,[5] which resulted in the Gilbert Islands becoming Kiribati upon independence.[6] The Colony of Tuvalu came into existence on 1 October 1975.[7] Tuvalu became fully independent within the Commonwealth on 1 October 1978. On 5 September 2000, Tuvalu became the 189th member of the United Nations.

The Tuvalu National Library and Archives hold "vital documentation on the cultural, social and political heritage of Tuvalu", including surviving records from the colonial administration, as well as Tuvalu government archives.[8]

Early history

[edit]

Tuvaluans are a Polynesian people, with the origins of the people of Tuvalu addressed in the theories regarding migration into the Pacific that began about 3000 years ago.[9] There is evidence for a dual genetic origin of Pacific Islanders in Asia and Melanesia, which results from an analysis of Y chromosome (NRY) and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) markers; there is also evidence that Fiji playing a pivotal role in west-to-east expansion within Polynesia.[10]

During pre-European-contact times there was frequent canoe voyaging between the islands, as Polynesian navigation skills are recognised to have allowed deliberate journeys on double-hulled sailing canoes or outrigger canoes.[11] Eight of the nine islands of Tuvalu were inhabited; thus the name, Tuvalu, means "eight standing together" in Tuvaluan (compare to *walo meaning "eight" in Proto-Austronesian). Possible evidence of fire in the Caves of Nanumanga may indicate human occupation thousands of years before that. The pattern of settlement that is believed to have occurred is that the Polynesians spread out from the Samoan Islands into the Tuvaluan atolls, with Tuvalu providing a stepping stone to migration into the Polynesian Outlier communities in Melanesia and Micronesia.[12][13][14][15]

An important creation myth of the islands of Tuvalu is the story of te Pusi mo te Ali (the Eel and the Flounder) who created the islands of Tuvalu; te Ali (the flounder) is believed to be the origin of the flat atolls of Tuvalu and te Pusi (the eel) is the model for the coconut palms that are important in the lives of Tuvaluans. The stories as to the ancestors of the Tuvaluans vary from island to island. On Niutao the understanding is that their ancestors came from Samoa in the 12th or 13th century.[16] On Funafuti and Vaitupu the founding ancestor is described as being from Samoa;[17][18] whereas on Nanumea the founding ancestor is described as being from Tonga.[17]

These stories can be linked to what is known about the Samoa-based Tu'i Manu'a Confederacy, ruled by the holders of the Tu'i Manú'a title, which confederacy likely included much of Western Polynesia and some outliers at the height of its power in the 10th and 11th centuries.

Tuvalu was also thought to have been visited by Tongans in the mid-13th century and was within Tonga's sphere of influence.[18] Captain James Cook observed and recorded his accounts of the Tuʻi Tonga kings during his visits to the Friendly Isles of Tonga.[19][20][21] By observing such Pacific cultures as Tuvalu and Uvea, the influence of the Tuʻi Tonga line of Tongan kings and the existence of the Tuʻi Tonga Empire, which originated in the 10th century, was quite strong and has had more of an impact in Polynesia and also parts of Micronesia than the Tu'i Manu'a.

The oral history of Niutao recalls that in the 15th century Tongan warriors were defeated in a battle on the reef of Niutao. Tongan warriors also invaded Niutao later in the 15th century and again were repelled. A third and fourth invasion of Tongan occurred in the late 16th century, again with the Tongans being defeated.[16]

Tuvalu is on the western boundary of the Polynesian Triangle so that the northern islands of Tuvalu, particularly Nui, have links to Micronesians from Kiribati.[17] The oral history of Niutao also recalls that during the 17th century warriors invaded from the islands of Kiribati on two occasions and were defeated in battles fought on the reef.[16]

Voyages by Europeans in the Pacific

[edit]

Tuvalu was first sighted by Europeans on 16 January 1568, during the voyage of Álvaro de Mendaña de Neira, Spanish explorer and cartographer, who sailed past the island of Nui, and charted it as Isla de Jesús (Spanish for "Island of Jesus"). This was because the previous day had been the feast of the Holy Name. Mendaña made contact with the islanders but was unable to land.[22] During Mendaña's second voyage across the Pacific he passed Niulakita on 29 August 1595, which he named La Solitaria.[22][23] Captain John Byron passed through the islands of Tuvalu in 1764 during his circumnavigation of the globe as captain of the Dolphin (1751).[24] Byron charted the atolls as Lagoon Islands.

The first recorded sighting of Nanumea by Europeans was by Spanish naval officer Francisco Mourelle de la Rúa who sailed past it on 5 May 1781 as captain of the frigate La Princesa, when attempting a southern crossing of the Pacific from the Philippines to New Spain. He charted Nanumea as San Augustin.[25][26] Keith S. Chambers and Doug Munro (1980) identified Niutao as the island that Mourelle also sailed past on 5 May 1781, thus solving what Europeans had called The Mystery of Gran Cocal.[23] Mourelle's map and journal named the island El Gran Cocal ('The Great Coconut Plantation'); however, the latitude and longitude was uncertain. Longitude could only be reckoned crudely as accurate chronometers were not available until the late 18th century. Laumua Kofe (1983)[27] accepts Chambers and Munro's conclusions, with Kofe describing Mourelle's ship La Princesa, as waiting beyond the reef, with Nuitaoans coming out in canoes, bringing some coconuts with them. La Princesa was short of supplies but Mourelle was forced to sail on – naming Niutao, El Gran Cocal ('The Great Coconut Plantation').[27]

In 1809, Captain Patterson in the brig Elizabeth sighted Nanumea while passing through the northern Tuvalu waters on a trading voyage from Port Jackson, Sydney, Australia to China.[25] In May 1819, Arent Schuyler de Peyster, of New York, captain of the armed brigantine or privateer Rebecca, sailing under British colours,[28][29] passed through the southern Tuvaluan waters while on a voyage from Valparaíso to India; de Peyster sighted Funafuti, which he named Ellice's Island after an English politician, Edward Ellice, the Member of Parliament for Coventry and the owner of the Rebecca's cargo.[27][30][31][32] The next morning, de Peyster sighted another group of about seventeen low islands forty-three miles northwest of Funafuti, which was named "De Peyster's Islands."[33] It is the first name, Nukufetau, that was eventually used for this atoll.

In 1820 the Russian explorer Mikhail Lazarev visited Nukufetau as commander of the Mirny.[27] Louis Isidore Duperrey, captain of La Coquille, sailed past Nanumanga in May 1824 during a circumnavigation of the earth (1822–1825).[34] A Dutch expedition by the frigate Maria Reigersberg[35] under captain Koerzen, and the corvette Pollux under captain C. Eeg, found Nui on the morning of 14 June 1825 and named the main island (Fenua Tapu) as Nederlandsch Eiland.[36]

-

Dutch map of Nui atoll, made in June 1825.

-

View of Fenua Tapu, Nui atoll.

-

View of Nui atoll.

Whalers began roving the Pacific, although visiting Tuvalu only infrequently because of the difficulties of landing on the atolls. Captain George Barrett of the Nantucket whaler Independence II has been identified as the first whaler to hunt the waters around Tuvalu.[30] In November 1821 he bartered coconuts from the people of Nukulaelae and also visited Niulakita.[23] A shore camp was established on Sakalua islet of Nukufetau, where coal was used to melt down the whale blubber.[37]

For less than a year between 1862 and 1863, Peruvian ships engaged in the so-called "blackbirding" trade, combed the smaller islands of Polynesia from Easter Island in the eastern Pacific to Tuvalu and the southern atolls of the Gilbert Islands (now Kiribati), seeking recruits to fill the extreme labour shortage in Peru, including workers to mine the guano deposits on the Chincha Islands.[38] On Funafuti and Nukulaelae, the resident traders facilitated the recruiting of the islanders by the "blackbirders".[39] The Rev. Archibald Wright Murray,[40] the earliest European missionary in Tuvalu, reported that in 1863 about 180 people[41] were taken from Funafuti and about 200 were taken from Nukulaelae,[42] as there were fewer than 100 of the 300 recorded in 1861 as living on Nukulaelae.[43][44]

Trading firms & traders

[edit]

John (also known as Jack) O'Brien was the first European to settle in Tuvalu, he became a trader on Funafuti in the 1850s. He married Salai, the daughter of the paramount chief of Funafuti. The Sydney firms of Robert Towns and Company, J. C. Malcolm and Company, and Macdonald, Smith and Company, pioneered the coconut-oil trade in Tuvalu.[39] The German firm of J.C. Godeffroy und Sohn of Hamburg[45] established operations in Apia, Samoa. In 1865 a trading captain acting on behalf of J.C. Godeffroy und Sohn obtained a 25-year lease to the eastern islet of Niuoko of Nukulaelae atoll.[46]

For many years the islanders and the Germans argued over the lease, including its terms and the importation of labourers, however the Germans remained until the lease expired in 1890.[46] By the 1870s J. C. Godeffroy und Sohn began to dominate the Tuvalu copra trade, which company was in 1879 taken over by Handels-und Plantagen-Gesellschaft der Südsee-Inseln zu Hamburg (DHPG). Competition came from Ruge, Hedemann & Co, established in 1875,[45] which was succeeded by H. M. Ruge and Company, and from Henderson and Macfarlane of Auckland, New Zealand.[47]

These trading companies engaged palagi traders who lived on the islands, some islands would have competing traders with dryer islands only have a single trader. Louis Becke, who later found success as a writer, was a trader on Nanumanga, working with the Liverpool firm of John S. de Wolf and Co., from April 1880 until the trading-station was destroyed later that year in a cyclone. He then became a trader on Nukufetau.[48][49] George Westbrook and Alfred Restieaux operated trade stores on Funafuti, which were destroyed in a cyclone that struck in 1883.[50]

H. M. Ruge and Company, a German trading firm that operated from Apia, Samoa, caused controversy when it threatened to seize the entire island of Vaitupu unless a debt of $13,000 was repaid.[51] The debt was the result of the failed operations of the Vaitupu Company, which had been established by Thomas William Williams, with part of the debt relating to the attempts to operate the trading schooner Vaitupulemele.[52] The Vaitupuans continue to celebrate Te Aso Fiafia (Happy Day) on 25 November of each year. Te Aso Fiafia commemorates 25 November 1887 which was the date on which the final instalment of the debt of $13,000 was repaid.[53]

From the late 1880s changes occurred with steamships replacing sailing vessels. Over time the number of competing trading companies diminished, beginning with Ruge's bankruptcy in 1888 followed by the withdrawal of the DHPG from trading in Tuvalu in 1889/90. In 1892 Captain Edward Davis of HMS Royalist, reported on trading activities and traders on each of the islands visited. Captain Davis identified the following traders in the Ellice Group: Edmund Duffy (Nanumea); Jack Buckland (Niutao); Harry Nitz (Vaitupu); John (also known as Jack) O'Brien (Funafuti); Alfred Restieaux and Emile Fenisot (Nukufetau); and Martin Kleis (Nui).[54] The 1880s was the time at which the greatest number of palagi traders lived on the atolls.[39] In 1892 the traders either acted as agent for Henderson and Macfarlane, or traded on their own account.[55]

From around 1900, Henderson and Macfarlane operating their vessel SS Archer in the South Pacific with a trading route to Fiji and the Gilbert and Ellice Islands.[39][56] New competition came from Burns Philp, operating from what is now Kiribati, with competition from Levers Pacific Plantations starting in 1903. Captain Ernest Frederick Hughes Allen of the Samoa Shipping and Trading Company competed for copra in the Ellice Islands, and the sale of goods to the islanders, when he built a trading store on Funafuti in 1911. In June 1914 he made Funafuti the operational base of the company, until the company was liquidated in 1925.[57] Burns Philp continued to operate in the Ellice Islands, the company transferred the wooden auxiliary schooner Murua (253 tons) to the Tarawa - Ellice Islands run, until the vessel was wrecked at Nanumea in April 1921.[39][58]

After the high point in the 1880s, the numbers of palagi traders in Tuvalu declined.[39] In the 1890s, structural changes occurred in the operation of the Pacific trading companies; they moved from a practice of having traders resident on each island to instead becoming a business operation where the supercargo (the cargo manager of a trading ship) would deal directly with the islanders when a ship visited an island.[39] By 1909 there were no resident palagi traders representing the trading firms.[59][60] The last of the traders were Martin Kleis on Nui,[60][61] Fred Whibley on Niutao and Alfred Restieaux on Nukufetau;[62][63] who remained in the islands until their deaths.

Tuvaluans became responsible for operating trading stores on each island.[39] In 1926, Donald Gilbert Kennedy was the headmaster of Elisefou (New Ellice) on Vaitupu. He was instrumental in establishing the first co-operative store (fusi) on Vaitupu, which became a model for the bulk purchasing and selling cooperative stores established in the Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony to replace the stores operated by Palangi traders.[64]

Scientific expeditions & travellers

[edit]

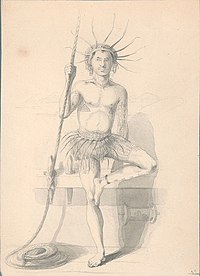

The United States Exploring Expedition, under Charles Wilkes, visited Funafuti, Nukufetau and Vaitupu in 1841.[65][66] During the visit, Alfred Thomas Agate, engraver and illustrator, recorded the clothing and tattoo patterns of men of Nukufetau.[67]

In 1885 or 1886, the New Zealand photographer Thomas Andrew visited Funafuti[68] and Nui.[69][70]

In 1890 Robert Louis Stevenson, his wife Fanny Vandegrift Stevenson, and her son Lloyd Osbourne sailed on the Janet Nicoll, a trading steamer owned by Henderson and Macfarlane of Auckland, New Zealand, which operated between Sydney, Auckland and into the central Pacific. The Janet Nicoll visited three of the Ellice Islands; while Fanny records that they made landfall at Funafuti, Niutao and Nanumea; however Jane Resture suggests that it was more likely they landed at Nukufetau rather than Funafuti,[71] as Fanny describes meeting Alfred Restieaux and his wife Litia; however they had been living on Nukufetau since the 1880s.[62][63] An account of the voyage was written by Fanny Vandegrift Stevenson and published under the title The Cruise of the Janet Nichol,[72][Note 1] together with photographs taken by Robert Louis Stevenson and Lloyd Osbourne.

In 1894 Count Rudolf Festetics de Tolna,[73] his wife Eila (née Haggin) and her daughter Blanche Haggin visited Funafuti aboard the yacht Le Tolna.[74][75] Le Tolna spent several days at Funafuti with the Count photographing men and women on Funafuti.[76]

The boreholes on Funafuti at the site now called Darwin's Drill,[77] are the result of drilling conducted by the Royal Society of London for the purpose of investigating the formation of coral reefs and the question as to whether traces of shallow water organisms could be found at depth in the coral of Pacific atolls. This investigation followed the work on The Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs conducted by Charles Darwin in the Pacific. Drilling occurred in 1896, 1897 and 1911. In 1896 Professor Edgeworth David of the University of Sydney went to the Pacific atoll of Funafuti as part of the Funafuti Coral Reef Boring Expedition of the Royal Society, under Professor William Sollas.[78] There were defects in the boring machinery and the bore penetrated only slightly more than 100 feet (approx. 31 m).

Prof. Sollas published a report on the study of Funafuti atoll,[79] and Charles Hedley, a naturalist, at the Australian Museum, collected Invertebrate and Ethnological objects on Funafuti. The descriptions of these were published in Memoir III of the Australian Museum Sydney between 1896 and 1900. Hedley also write the General Account of the Atoll of Funafuti,[80] The Ethnology of Funafuti[81] and The Mollusca of Funafuti.[82][83] Edgar Waite also was part of the 1896 expedition and published an account of The mammals, reptiles, and fishes of Funafuti.[84] William Rainbow described the spiders and insects collected at Funafuti in The insect fauna of Funafuti.[85]

In 1897 Edgeworth David led a second expedition (that included George Sweet as second-in-command, and Walter George Woolnough) which succeeded in reaching a depth of 557 feet (170 m). David then organised a third expedition in 1898 which, under the leadership of Dr. Alfred Edmund Finckh, was successful in deepening the bore to 1,114 feet (340 m).[86][87] The results provided support for Charles Darwin's theory of subsidence.[88] Cara Edgeworth accompanied her husband on the second expedition and published a well-received account called Funafuti, or Three Months on a Coral Island.[78] Photographers on the expeditions recorded people, communities and scenes at Funafuti.[89]

Harry Clifford Fassett, captain's clerk and photographer, recorded people, communities and scenes at Funafuti in 1900 during a visit of USFC Albatross when the United States Fish Commission were investigating the formation of coral reefs on Pacific atolls.[90]

Pre-Christian beliefs

[edit]Laumua Kofe (1983) describes the objects of worship as varying from island to island, although ancestor worship was described by the Rev. Samuel James Whitmee in 1870 as being common practice.[91][92]

In 1896 Professor William Sollas went to Funafuti as the leader of the Funafuti Coral Reef Boring Expedition of the Royal Society, and with the assistance of Jack O'Brien (as interpreter), he recorded an oral history of Funafuti given by Erivara, the chief of Funafuti, which he published as The Legendary History of Funafuti.[93] Erivara provided an account of the kings (chiefs) of Funafuti and a description of the spiritual beliefs before the introduction of Christianity. The beliefs evolved over time. In the beginning the people worshipped the powers of nature, such as thunder and lightening, as well as birds and fishes.[93] Then the worship of spirits became the belief system, such as Tufakala who was named after a variety of seagull. Eventually the belief system was centred on the priests or spirit-masters (vaka-atua or vakatua), who were the intermediaries between the people and spirits, deities and fetish objects, such as an unusual red stone called the Teo.[93] Another fetish object was a hat made out of red, white and black pandanus leaves and adorned with white shells, called the Pulau, which was said to be the hat of Firapu, an ancestor who had been deified.[93] Daily activities such as fishing and cultivation of crops were connected to ceremonies involving the fetish objects and to specific spirits or deities. The vaka-atua were also the healers.[93] Erivara described the destruction of the fetish houses, and the influence of the vaka-atua, by the trader Jack O’Brien in the decade before the arrival of Christian missionaries on Funafuti.[93]

The arrival of Christian missionaries

[edit]Traders, such as Tom Rose at Nukulaelae and Robert Waters at Nui, actively proselytized Christianity. Rose by holding services on Sundays. Although Waters, and other traders, such Charlie Douglas at Niutao and Jack O’Brien at Funafuti, had economic motives in destroying the ancient religions so that the islanders were more focused on the copra and coconut oil trade.[39]

The first Christian missionary came to Tuvalu in 1861 when Elekana, a Christian deacon from Manihiki in the Cook Islands became caught in a storm and drifted for 8 weeks before landing at Nukulaelae.[94][95] Once there, Elekana began proselytizing Christianity.[27] He was trained at Malua Theological College, a London Missionary Society school in Samoa, before beginning his work in establishing what became the Church of Tuvalu.[27][96]

In 1865 the Rev. Archibald Wright Murray of the London Missionary Society – a Protestant congregationalist missionary society – arrived as the first European missionary where he too proselytized among the Ellice Islanders.[97] The Rev. Samuel James Whitmee visited the islands in 1870.[98] By 1878 Protestantism was well established with preachers on each island.[27] In the later 19th century the ministers of what became the Church of Tuvalu were predominantly Samoans,[99] who influenced the development of the Tuvaluan language and the music of Tuvalu.[100] Westbrook, a trader on Funafuti, reported that the pastors impose strict rules on all people on the island, including demanding attendance at church and forbidding cooking on a Sunday.[101][102]

Colonial administration

[edit]In 1886 Britain and Germany agreed to divide up the western and central Pacific, with each claiming a 'sphere of influence'.[103][4] In the previous decade German traders had become active in the Solomon Islands, New Guinea, Marshall Islands and the Caroline Islands. In 1877 the Governor of Fiji was given the additional title of High Commissioner for the Western Pacific. However, the claim of a 'sphere of influence' that included the Ellice Islands and the Gilbert Islands did not result in the immediate move to govern those islands.[4]

SMS Ariadne, a steam corvette of the German Kaiserliche Marine (Imperial Navy), called at Funafuti and Vaitupu in 1878.[104] Captain Werner imposed trade and friendship treaties on the islanders giving Germany most-favored-nation treatment, and he intervened to assist the DHPG trader at Vaitupu, Harry Nitz, in a dispute over land.[104] In 1883 SMS Hyäne, a gunboat, called at Funafuti.[104]

Ships of the Royal Navy known to have visited the islands in the 19th century are:

- Basilisk (1848), under Captain John Moresby,[105] visited the islands in July 1872.[106]

- Emerald (1876), under Captain William Maxwell, visited the islands in 1881.[107]

- HMS Miranda, under Commander Dyke Acland,[108][109] visited many of the islands in 1886.

- HMS Royalist, under Captain Edward Davis, visited each of the Ellice Islands in 1892 and reported on trading activities and traders on each of the islands visited.[110] Captain Davis reported that the islanders wanted him to hoist the British flag on the islands, however Captain Davis did not have any orders regarding such a formal act.[111]

- HMS Curacoa, under Captain Herbert Gibson, was sent to the Ellice Islands and between 9 and 16 October 1892. Captain Gibson visited each of the islands to make a formal declaration that the islands were to be a British protectorate.[4]

- HMS Penguin, under Captain Arthur Mostyn Field, delivered the Funafuti Coral Reef Boring Expedition of the Royal Society to Funafuti, arriving on 21 May 1896 and returned to Sydney on 22 August 1896.[112] The Penguin made further voyages to Funafuti to deliver the expeditions of the Royal Society in 1897 and 1898.[113] The surveys carried out by the Penguin resulted in the Admiralty Nautical Chart 2983 for the Ellice Islands.[114]

From 1892 to 1916 the Ellice Islands were administered as a British protectorate, as part of the British Western Pacific Territories (BWPT), by a Resident Commissioner based in the Gilbert Islands. The first Resident Commissioner was Charles Richard Swayne, who collected the ordinances of each island of Tuvalu that had been established by the Samoan pastors of the London Missionary Society. These ordinances were the basis of the Native Laws of the Ellice Islands that were issued by Swayne in 1894.[4] The Native Laws established and administrative structure for each island and well as prescribing criminal laws. The Native Laws also made it compulsory for children to attend school. On each island the High Chief (Tupu) was responsible for maintaining order; with a magistrate and policemen also responsible for maintaining order and enforcing the law. The High Chief was assisted by the councillors (Falekaupule).[4] The Falekaupule on each of the Islands of Tuvalu is the traditional assembly of elders or te sina o fenua (literally: "grey-hairs of the land" in the Tuvaluan language).[115] The Kaupule on each island is the executive arm of the Falekaupule. The second Resident Commissioner was William Telfer Campbell (1895–1909),[116] who established land registers that would assist in resolving disputes over title to land. Arthur Mahaffy was a District Officer in the Gilbert and Ellice Islands Protectorate from 1895 to 1897.[117] In 1909, Geoffrey B. W. Smith-Rewse was appointed as the District Officer to administer the Ellice Islands from Funafuti and remained in that position until 1915.

In 1916 the administration of the BWTP ended and the Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony was established, which existed from 1916 to 1974. In 1917 revised laws were issue, which abolished the office of High Chief and limited the number of members of the Kaupule on each island. Under the 1917 laws the Kaupule of each island could issue local regulations. Under the revised rules the magistrate was most important official and the senior person of the Kaupule was the deputy magistrate.[118] The Colony continued to be administered by the Resident Commissioner, based in the Gilbert Islands, with a District Officer based on Funafuti.[4]

In 1930 the Resident Commissioner, Arthur Grimble, issued revised laws, Regulations for the good Order and Cleanliness of the Gilbert and Ellice Islands. The Regulations removed the ability of the Kaupule to issue local regulations, and proscribed stringent rules of public and private behaviour. The attempts of the islanders to have the Regulations changed were ignored until Henry Evans Maude, a government officer, sent a copy to a member of the English Parliament.[4]

Donald Gilbert Kennedy arrived in 1923 and took charge of a newly established government school on Funafuti. The following year he transferred Elisefou school to Vaitupu as the food supply was better on that island. In 1932 Kennedy was appointed the District officer on Funafuti, which office he held until 1939. Colonel Fox-Strangways, was the Resident Commissioner of the Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony in 1941, who was located on Funafuti.[119]

After World War II,[119] Kennedy encouraged Neli Lifuka in the resettlement proposal that eventually resulted in the purchase of Kioa island in Fiji.[4][119][120]

The Pacific War and Operation Galvanic

[edit]

During the Second World War, as a British colony, the Ellice Islands were aligned with the Allies. Early in the war, the Japanese invaded and occupied Makin, Tarawa and other islands in what is now Kiribati, however their further expansion to other islands were delayed by their losses at the Battle of the Coral Sea.

The United States Marine Corps landed on Funafuti on 2 October 1942[121][Note 2] and on Nanumea and Nukufetau in August 1943. The Ellice Islands were used as a base to prepare for the subsequent seaborn attacks on the Gilbert Islands (Kiribati) that were occupied by Japanese forces.[123]

Coastwatchers were stationed on some of the islands to identify any Japanese activity, such as Neli Lifuka on Vaitupu.[119] The islanders assisted the American forces to build airfields on Funafuti, Nanumea and Nukufetau and to unload supplies from ships.[124] On Funafuti the islanders were shifted to the smaller islets so as to allow the American forces to build the airfield, a 76-bed hospital and Naval Base Funafuti on Fongafale islet.[122][125]

The construction of the airfields resulted in the loss of coconut trees and gardens, however, the islanders benefited from the food and luxury goods supplied by the American forces. The estimates of the loss of food producing trees was that 55,672 coconuts trees, 1,633 breadfruit trees and 797 pandanus trees were destroyed on those three islands.[Note 3] Building the runway at Funafuti involved the loss of land used for growing pulaka and taro with extensive excavation of coral from 10 borrow pits. [Note 4]

A detachment of the 2nd Naval Construction Battalion (the Seabees) built a sea plane ramp on the lagoon side of Fongafale islet for seaplane operations by both short and long range seaplanes and a compacted coral runway was constructed on Fongafale, which was 5,000 feet long and 250 feet wide and was then extended to 6,600 feet long and 600 feet wide.[128] On 15 December 1942 four VOS float planes (Vought OS2U Kingfisher) from VS-1-D14 arrived at Funafuti to carry out anti-submarine patrols.[129] PBY Catalina flying boats of US Navy Patrol Squadrons were stationed at Funafuti for short periods of time, including VP-34, which arrived at Funafuti on 18 August 1943 and VP-33, which arrived on 26 September 1943.[130]

In April 1943, a detachment of the 3rd Battalion constructed an aviation-gasoline tank farm on Fongafale. The 16th Battalion arrived in August 1943 to build Nanumea Airfield and Nukufetau Airfield.[128] The atolls were described as providing "unsinkable aircraft carriers"[131] during the preparation for the Battle of Tarawa and the Battle of Makin that commenced on 20 November 1943, which was the implementation of "Operation Galvanic".[132][133]

USS LST-203 was grounded on the reef at Nanumea on 2 October 1943 in order to land equipment. The rusting hull of the ship remains on the reef.[134] The Seabees also blasted an opening in the reef at Nanumea, which became known as the 'American Passage'.[132]

The 5th and 7th Defense Battalions were stationed in the Ellice Islands to provide the defense of various naval bases. The 51st Defense Battalion relieved the 7th in February 1944 on Funafuti and Nanumea until they were transferred to Eniwetok Atoll in the Marshall Islands in July 1944.[135]

The first offensive operation was launched from the airfield at Funafuti on 20 April 1943 when twenty-two B-24 Liberator bombers from 371 and 372 Bombardment Squadrons struck Nauru. The next day the Japanese made a predawn raid on the strip at Funafuti which destroyed one B-24 and caused damage to five other planes. On 22 April 12 B-24 aircraft struck Tarawa.[136] The airfield at Funafuti became the headquarters of the United States Army Air Forces VII Bomber Command in November 1943, directing operations against Japanese forces on Tarawa and other bases in the Gilbert Islands. USAAF B-24 Liberator bombers of the 11th Wing, 30th Bombardment Group, 27th Bombardment Squadron and 28th Bombardment Squadron operated from Funafuti Airfield, Nanumea Airfield and Nukufetau Airfield.[136] The 45th Fighter Squadron operated P-40Ns from Nanumea and Marine Attack Squadron 331 (VMA-331) operated Douglas SBD Dauntless dive bombers from Nanumea and Nukufetau.[137]

Funafuti suffered air attacks during 1943. Casualties were limited, although tragedy was averted on 23 April 1943, when 10 to 20 people took refuge in the concrete walled, pandanus-thatched church.[138] Corporal Fonnie Black Ladd, USMCR, persuaded them to get into dugouts, then a bomb struck the church shortly after;[139][140] in that raid, 2 American soldiers and an elderly Tuvaluan man named Esau were killed.[138] Japanese airplanes continued to raided Funafuti, attacking on 12 & 13 November 1943 and again on 17 November 1943.

USN Patrol Torpedo Boats (PTs) were based at Funafuti from 2 November 1942 to 11 May 1944.[141] Squadron 1B arrived on 2 November 1942 with USS Hilo as the support ship, which remained until 25 November 1942.[142] On 22 December 1942 Squadron 3 Division 2 (including PTs 21, 22, 25 & 26) arrived with the combined squadron commanded by Lt. Jonathan Rice. In July 1943 Squadron 11-2 (including PTs 177, 182, 185, and 186) under the command of Lt. John H. Stillman relieved Squadron 3–2. The PT Boats operated from Funafuti against Japanese shipping in the Gilbert Islands;[141] although they were primarily involved in patrol and rescue duty.[143] A Kingfisher float plane rescued Captain Eddie Rickenbacker and aircrew from life-rafts near Nukufetau, with PT 26 from Funafuti completing the rescue.[142][144][145] Motor Torpedo Boat operations ceased at Funafuti in May 1944 and Squadron 11-2 was transferred to Emirau Island, New Guinea.[132]

The Alabama (BB-60) reached Funafuti on 21 January 1944. The Alabama left the Ellice Islands on 25 January to participate in "Operation Flintlock" in the Marshall Islands. By the middle of 1944, as the fighting moved further north towards Japan, the Americans forces were redeployed. By the time the war ended in 1945 nearly all of them had departed, together with their equipment. After the war the military airfield on Funafuti was developed into Funafuti International Airport.

Transition to self-government

[edit]The formation of the United Nations Organisation after World War II resulted in the United Nations Special Committee on Decolonization committing to a process of decolonization; as a consequence the British colonies in the Pacific started on a path to self-determination.[118][146] The initial focus was on the development of the administration of the Gilbert and Ellice Islands. In 1947 Tarawa, in the Gilbert Islands, was made the administrative capital. This development included establishing the King George V Secondary School for boys and the Elaine Bernacchi Secondary School for girls.[118]

A Colony Conference was organised at Marakei in 1956, which was attended by officials and representatives from each island in the Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony, conferences were held every 2 years until 1962. The development of administration continued with the creation in 1963 of an Advisory Council of 5 officials and 12 representatives who were appointed by the Resident Commissioner.[118][147] In 1964 an Executive Council was established with 8 officials and 8 representatives. The Resident Commissioner was now required to consult the Executive Council regarding the creation of laws to making decisions that affected the Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony.[147]

The system of local government on each island established in the colonial era continued until 1965 when Island Councils were established with the islanders electing the councillors who then choose the President of the council. The Executive Officer of each Local Council was appointed by the central government.[118]

A constitution was introduced in 1967, which created a House of Representatives for the Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony that comprised 7 appointed officials and 23 members elected by the islanders. Tuvalu elected 4 members of the House of Representatives. The 1967 constitution also established the Governing Council. The House of Representatives only had the authority to recommend laws; the Governing Council had the authority to enact laws following a recommendation from the House of Representatives.[147]

A select committee of the House of Representatives was established to consider whether the constitution should be changes to give legislative power to the House of Representatives. The proposal was that Ellice Islanders would be allocated 4 seats out of a 24-member parliament, which reflected the differences in populations between Elice Islanders and Gilbertese.[148] It became apparent that the Tuvaluans were concerned about their minority status in the Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony and the Tuvaluans wanted equal representation to that of the I-Kiribati. A new constitution was introduced in 1971, which provided that each of the islands of Tuvalu (except Niulakita) elected one representative. However, that did not end the Tuvaluan movement for independence.[149]

In 1974 ministerial government was introduced to the Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony through a change to the Constitution.[147] In that year a general election was held;[150] and a referendum was held in 1974 to determine whether the Gilbert Islands and Ellice Islands should each have their own administration.[5][151] The result of the referendum, was that 3,799 Elliceans voted for separation from the Gilbert Islands and continuance of British rule as a separate colony, and 293 Elliceans voted to remain as the Gilbert and Ellice Islands colony. There were 40 spoilt papers.[152]

As a consequence of the referendum, separation occurred in two stages. The Tuvaluan Order 1975, which took effect on 1 October 1975, recognised Tuvalu as a separate British dependency with its own government.[7] The second stage occurred on 1 January 1976 when separate administrations were created out of the civil service of the Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony.[153]

Elections to the House of Assembly of the British Colony of Tuvalu were held on 27 August 1977; with Toaripi Lauti being appointed Chief Minister in the House of Assembly of the Colony of Tuvalu on 1 October 1977. The House of Assembly was dissolved in July 1978 with the government of Toaripi Lauti continuing as a caretaker government until the 1981 elections were held.[154]

Toaripi Lauti became the first Prime Minister of the Parliament of Tuvalu or Palamene o Tuvalu on 1 October 1978 when Tuvalu became an independent nation.[118][147]

The place at which the parliament sits is called the Vaiaku maneapa.[155]

Local government of each island by the Falekaupule and Kaupule

[edit]

The Falekaupule on each of the Islands of Tuvalu is the traditional assembly of elders or te sina o fenua (literally: "grey-hairs of the land" in the Tuvaluan language).[115] Under the Falekaupule Act (1997),[156] the powers and functions of the Falekaupule are now shared with the Kaupule on each island, which is the executive arm of the Falekaupule, whose members are elected. The Kaupule has an elected president – pule o kaupule; an appointed treasurer – ofisa ten tupe; and is managed by a committee appointed by the Kaupule.[156]

The Falekaupule Act (1997) defines the Falekaupule to mean the "traditional assembly in each island ... composed in accordance with the Aganu of each island". Aganu means traditional customs and culture.[156] The Falekaupule on each island has existed from time immemorial and continue to act as the local government of each island.[157]

The maneapa on each island is traditionally an open meeting place where the chiefs and elders deliberate and make decisions.[155] In modern times a maneapa is a building in which people meet for community meetings or celebrations. The maneapa system is the rule of the traditional chiefs and elders.[155]

Broadcasting and news media

[edit]Following independence the only newspaper publisher and public broadcasting organisation in Tuvalu was the Broadcasting and Information Office (BIO) of Tuvalu.[158][159] The Tuvalu Media Corporation (TMC) was a government-owned corporation established in 1999 to take over the radio and print based publications of the BIO. However, in 2008 operating as a corporation was determined not to be commercial viable and the Tuvalu Media Corporation then became the Tuvalu Media Department (TMD) under the Office of the Prime Minister.[160]

Health services

[edit]A hospital was established at Funafuti in 1913 at the direction of Geoffrey B. W. Smith-Rewse, during his tenure as the District Officer at Funafuti from 1909 to 1915.[161] At this time Tuvalu was known as the Ellice Islands and was administered as a British protectorate as part of the British Western Pacific Territories. In 1916 the Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony was established. From 1916 to 1919 the hospital was under the supervision of Dr J. G. McNaughton, when he resigned the position remained vacant until 1930, when Dr D. C. Macpherson was appointed the medical doctor at the hospital. He remain in the position until 1933, when he was appointed to a position in Suva, Fiji.[126]

During the time of the colonial administration, Tuvaluans provided medical services at the hospital after receiving training to become doctors or nurses (the male nurses were known as 'Dressers') at the Suva Medical School, which changed its name to Central Medical School in 1928 and which later became the Fiji School of Medicine.[162] Training was provided to Tuvaluans who graduated with the title Native Medical Practitioners. The medical staff on each island were assisted by women's committees which, from about 1930, played an important role in health, hygiene and sanitation.[126]

During World War II the hospital on Fongafale atoll was dismantled as the American forces built an airfield on this atoll. The hospital was shifted to Funafala atoll under the responsibility of Dr Ka, while Dr Simeona Peni provided medical services to the American forces at the 76-bed hospital on Fongafale that was built by the Americans at Vailele. After the war the hospital returned to Fongafale and used the American hospital until 1947 when a new hospital was built. However, the hospital built in 1947 was incomplete because of problems in the supply of building materials. Cyclone Bebe struck Funafuti in late October 1972 and caused extensive damage to the hospital.[126]

In 1974 Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony was dissolved and the Colony of Tuvalu was established. Tuvalu regained independence on 1 October 1978. A new 38-bed central hospital was built at Fakaifou on Fongafale atoll, with New Zealand aid grant. It was completed in 1975 and officially opened on 29 September 1978 by Princess Margaret after whom the hospital was named.[118] The building now occupied by the Princess Margaret Hospital was completed in 2003 with the building financed by the Japanese government.[163] The Department of Health also employ nine or ten nurses on the outer islands to provide general nursing and midwifery services.[53][126]

Non-government organizations provide health services, such as the Tuvalu Red Cross Society; Fusi Alofa Association Tuvalu (which is an association for persons with disabilities);[164] the Tuvalu Family Health Association (which provides training and support on sexual and reproductive health); and the Tuvalu Diabetics Association (which provides training and support on diabetes).[165]

Tuvaluans have consulted, and continue to consult, a herbal medicine practitioner (Tufuga or tofuga). Tuvaluans would see a Tufuga both as a substitute for treatment from a trained doctor of medicine and as an additional source of medical assistance while also accessing orthodox medical treatment. On the island of Nanumea in 1951, Malele Tauila, was a well-known Tufuga.[126] An example of a herbal medicine derived from local flora, is a treatment for ear ache made out of a pandanus (pandanus tectorius) tree's root.[53] Tufuga also provide a form of massage.[53]

Education in Tuvalu

[edit]The development of the education system

[edit]The London Missionary Society (LMS) established a mission school at Papaelise on Funafuti; Sarah Jolliffe was the teacher for some years.[57] The LMS established a primary school at Motufoua on Vaitupu in 1905. The purpose was to prepare young men for entry into the LMS seminary in Samoa. This school evolved into the Motufoua Secondary School.[166] There was also a school called Elisefou (New Ellice) on Vaitupu. The school was established in Funafuti in 1923 and moved to Vaitupu in 1924. It closed in 1953. Its first headmaster, Donald Gilbert Kennedy (1923–1932), was a known disciplinarian who would not hesitate to discipline his students. He was succeeded as headmaster by Melitiana of Nukulaelae.[64] In 1953 government schools were established on Nui, Nukufetau and Vaitupu and in the following year on the other islands. These schools replace the existing primary schools. However, the schools did not have capacity for all children until 1963, when the government improved educational standards.[167]

From 1953 until 1975 Tuvaluan students could sit the selection tests for admission to the King George V Secondary School for boys (which opened in 1953) and the Elaine Bernacchi Secondary School for girls. These schools were located on Tarawa in the Gilbert Islands (now Kiribati), which was the administrative centre of the Gilbert and Ellice Islands colony. In 1965 King George V and Elaine Bernacchi School were merged.[168] Tarawa was also the location for training institutions such as the teachers college and the nursing centre.[167]

The activities of the LMS were taken over by the Church of Tuvalu. From 1905 to 1963 Motufoua only admitted students from LMS church schools. In 1963 the LMS and the government of Tuvalu began to co-operate in providing education and students were enrolled from government schools. In 1970 a secondary school for girls was opened at Motufoua.[167] In 1974, the Ellice Islanders voted for separate British dependency status as Tuvalu, separating from the Gilbert Islands which became Kiribati. The following year the students that attended school on Tawara were transferred to Motufoua. From 1975 the Church of Tuvalu and the government jointly administer the School.[167] Eventually administration of Motufoua Secondary School became the sole responsibility of the Department of Education of Tuvalu.

Fetuvalu Secondary School, a day school operated by the Church of Tuvalu, is located on Funafuti.[169][170] The school re-opened in 2003 having been closed for 5 years.[171][172]

In 2011, Fusi Alofa Association Tuvalu (FAA – Tuvalu) established a school for children with special needs.[164]

Community Training Centres (CTCs) have been established within the primary schools on each atoll. The CTSs provide vocational training to students that do not progress beyond Class 8. The CTCs offer training in basic carpentry, gardening and farming, sewing and cooking. At the end of their studies the graduates of CTC can apply to continue studies either at Motufoua Secondary School or the Tuvalu Maritime Training Institute (TMTI). Adults can also attend courses at the CTCs.[173]

Education in the 21st century

[edit]The University of the South Pacific (USP) operates an Extension Centre in Funafuti.[174] The USP organised a seminar in June 1997 for the purposes of the Tuvalu community informing USP of their requirements for future tertiary education and training, and to assist in the development of the Tuvaluan educational policy.[175] The Government of Tuvalu, with the assistance of the Asian Development Bank, developed a draft master plan to develop the educational sector, with the draft plan being discussed at a workshop in June 2004.[176]

Education in Tuvalu has been the subject of reviews including in Tuvalu-Australia Education Support Program (TAESP) reports beginning in 1997, the Westover Report (AusAID 2000), the report on Quality in Education and Training by the Ministry of Education and Sport, Tuvalu (MOES 2002), the Tuvalu Technical and Vocational Education and Training Study (NZAID 2003), the report on Tuvalu Curriculum Framework (AusAID 2003)[176] with further development of the National Curriculum (AusAID 2004).[177]

The priorities of the Education Department in 2012–2015 include providing the equipment for elearning at Motufoua Secondary School and setting up a multimedia unit in the department to develop and deliver content in all areas of the curriculum across all level of education.[178]

Atufenua Maui and educators from Japan have worked on the implementation of an e-learning pilot system at Motufoua Secondary School that applies the Modular Object Oriented Dynamic Learning Environment (Moodle).[179] The e-learning system is intended to benefit students at Motufoua Secondary School and to provide computer skills to students who will enter the tertiary level of education outside Tuvalu.[180]

In 2010, there were 1,918 students who were taught by 109 teachers (98 certified and 11 uncertified). The teacher-pupil ratio for primary schools in Tuvalu is around 1:18 for all schools with the exception of Nauti school, which has a student-teacher ratio of 1:27. Nauti School on Funafuti is the largest primary in Tuvalu with more than 900 students (45 percent of the total primary school enrolment). The pupil-teacher ratio for Tuvalu is low compared to the Pacific region, which has a ratio of 1:29.[181]

Four tertiary institutions offer technical and vocational courses. Tuvalu Maritime Training Institute (TMTI), Tuvalu Atoll Science Technology Training Institute (TASTII), Australian Pacific Training Coalition (APTC) and University of the South Pacific (USP) Extension Centre.[182] The services provided at the USP campus include career counselling, Student Learning Support, IT Support (Moodle, React, Computer Lab and Wi Fi) and library services (IRS).[183]

Education and the national strategy plans: Te Kakeega III and Te Kete

[edit]The education strategy is described in Te Kakeega II (Tuvalu National Strategy for Sustainable Development 2005–2015)[157] and Te Kakeega III – National Strategy for Sustainable Development-2016–2020.[184]

Te Kakeega II has identified the following key objectives in regards the development of the education system: (i) Curriculum and Assessment Improvement, (ii) Increased student participation by ensuring access and equity for students with special needs, (iii) Improved quality and efficiency of management, (iv) Human Resource Development, (v) Strengthened community partnerships and develop a culture of working together.[157] In 2011 meetings were held to review Te Kakeega II and the Tuvalu Education Strategic Plan (TESP) II; Tuvalu Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) Report.[53] In 2013 a report was published on improving the quality of education as part of the Millennium Development Goal Acceleration Framework.[181]

Te Kakeega III describes the education strategy as being:

Most TK II goals in education continue in TK III – in broad terms to continue to equip people with the knowledge and skills they need to achieve a higher degree of self-reliance in a changing world. TKII strategies targeted improvements in teaching quality/overall education standards through teacher training, better and well-maintained school facilities, more school equipment and supplies, and the introduction of a stronger, consistent and more appropriate curriculum. The expansion and improvement of technical and vocational training was another objective, as was serving the special needs of students with disabilities and preschoolers."[184]

In the national strategy plan for 2021–2030,[185] the name ”Kakeega” was replaced by “Te Kete” which is the name of a domestic traditional basket woven from green or brown coconut leaves.[186] Symbolically, “Te Kete” has biblical significance for Tuvaluan Christian traditions by referencing to the basket or the cradle that saved the life of Moses.[186]

Heritage and culture

[edit]Architecture

[edit]The traditional buildings of Tuvalu used plants and trees from the native broadleaf forest,[187] including timber from pouka (Hernandia peltata); ngia or ingia bush (Pemphis acidula); miro (Thespesia populnea); tonga (Rhizophora mucronata); fau or fo fafini, or woman's fibre tree (Hibiscus tiliaceus).[187] Fibre is from coconut; ferra, native fig (Ficus aspem); fala, screw pine or Pandanus.[187] The buildings were constructed without nails and were lashed together with a plaited sennit rope that was handmade from dried coconut fibre.[188]

Following contact with Europeans, iron products were used including nails and corrugated roofing material. Modern buildings in Tuvalu are constructed from imported building materials, including imported timber and concrete.[188]

Church and community buildings (maneapa) are usually coated with white paint that is known as lase, which is made by burning a large amount of dead coral with firewood. The whitish powder that is the result is mixed with water and painted on the buildings.[189]

Art of Tuvalu

[edit]The women of Tuvalu use cowrie and other shells in traditional handicrafts.[190] The artistic traditions of Tuvalu have traditionally been expressed in the design of clothing and traditional handicrafts such as the decoration of mats and fans.[190] Crochet (kolose) is one of the art forms practised by Tuvaluan women.[191][192] The material culture of Tuvalu uses traditional design elements in artefacts used in everyday life such as the design of canoes and fish hooks made from traditional materials.[193][194]

Traditional uses of material from the native broadleaf forest

[edit]Charles Hedley (1896) identified the uses of plants and trees from the native broadleaf forest as including:[187]

- Food plants: Coconut; and Ferra, native fig (Ficus aspem).[187]

- Fibre: Coconut; Ferra; Fala, Screw Pine, Pandanus; Fau or Fo fafini, or woman's fibre tree (Hibiscus tiliaceus).[187]

- Timber: Fau or Fo fafini; Pouka, (Hernandia peltata); Ngia or Ingia, (Pemphis acidula); Miro, (Thespesia populnea); and Tonga (Tongo), (Rhizophora mucronata).[187]

- Dye: Valla valla, (Premna tahitensis); Tonga (Tongo), (Rhizophora mucronata); and Nonou (Nonu), (Morinda citrifolia).[187]

- Scent: Fetau, (Calophyllum inophyllum); Jiali, (Gardenia taitensis); and Boua (Guettarda speciosa); Valla valla, (Premna tahitensis); and Crinum.[187]

- Medicinal: Tulla tulla, (Triumfetta procumbens); Nonou (Nonu), (Morinda citrifolia); Tausoun, (Heliotropium foertherianum); Valla valla, (Premna tahitensis); Talla talla gemoa, (Psilotum triquetrum); Lou, (Cardamine sarmentosa); and Lakoumonong, (Wedelia strigulosa).[187]

These plants and trees are still used in the Art of Tuvalu to make traditional artwork and handicraft. Tuvaluan women continue to make Te titi tao, which is a traditional skirt made of dried pandanus leaves that are dyed using Tongo (Rhizophora mucronata) and Nonu (Morinda citrifolia).[195] The art of making a titi tao is passed down from Fafinematua (elder women) to the Tamaliki Fafine (young women) who are preparing for their first Fatele.[195]

Traditional fishing canoes (paopao)

[edit]The people of Tuvalu construct traditional outrigger canoes. A 1996 survey conducted on Nanumea found some 80 canoes. In 2020 there are about 50 canoes with up to five households practicing traditional canoe building. However, the availability of mature fetau trees (Calophyllum inophyllum) on the island is declining.[196]

An outrigger canoe would be constructed by a skilled woodworker (tofuga or tufunga) of the family, on whose land was a suitable tree. The canoe builder would call on the assistance of the tufunga of other families.[193] The ideal shape the canoe was that of the body of a whale (tafola), while some tufunga shaped the canoe to reflect the body of a bonito (atu). Before steel tools became available, the tufunga or used shell and stone adzes, which were rapidly blunted when used. With a group of up to ten tufunga building a canoe, one or two would work on the canoe, while others were engaged in sharpening the edge of one adze after another. Each morning, the tufunga would conduct a religious ceremony (lotu-a-toki) over the adzes before the commencement of work. When steel tools became available, two tufunga would be sufficient to build a canoe.[193]

Donald Gilbert Kennedy described the construction of traditional outrigger canoes (paopao) and of the variations of single-outrigger canoes that had been developed on Vaitupu and Nanumea.[193] Gerd Koch, an anthropologist, Koch visited the atolls of Nanumaga, Nukufetau and Niutao, in 1960–61, and published a book on the material culture of the Ellice Islands, which also described the canoes of those islands.[194]

The variations of single-outrigger canoes that had been developed on Vaitupu and Nanumea were reef-type or paddled canoe; that is, they were designed for carrying over the reef and paddled, rather than sailed. The traditional outrigger canoes from Nui were constructed with an indirect type of outrigger attachment and the hull is double-ended, with no distinct bow and stern. These canoes were designed to be sailed over the Nui lagoon.[197] The booms of the outrigger are longer than those found in other designs of canoes from the other islands.[193] This made the Nui canoe more stable when used with a sail than the other designs.[197]

Dance and music

[edit]

The traditional music of Tuvalu consists of a number of dances, including fakaseasea, fakanau and fatele.[198]

Heritage

[edit]The aliki were the leaders of traditional Tuvaluan society.[199] The aliki had the tao aliki, or assistant chiefs who were the mediators between the islanders and the aliki, who were responsible for the administration and supervision of daily activities on the island, such as arranging fishing expeditions and communal works.[199] The role of the sisters and daughters of the aliki was to ensure that the women were engaged in activities that were traditionally done by the women, such as weaving baskets, mats, baskets, string, clothing and other materials.[199] The elders of the community were male heads of each family (sologa).[199] Each family would have a task (pologa) to perform for the community, such as being a skilled builder of canoes or houses (tofuga or tufunga), or being skilled at fishing, farming, or as a warrior to defend the island.[199] The skills of a family are passed on from parents to children.

An important building is the falekaupule or maneapa, the traditional island meeting hall,[157] where important matters are discussed and which is also used for wedding celebrations and community activities such as a fatele involving music, singing and dancing.[115] Falekaupule is also used as the name of the council of elders – the traditional decision-making body on each island. Under the Falekaupule Act, Falekaupule means "traditional assembly in each island ... composed in accordance with the Aganu of each island". Aganu means traditional customs and culture.[157]

Tuvalu does not have any museums, however the creation of a Tuvalu National Cultural Centre and Museum is part of the government's strategic plan for 2018–24.[200][201]

Land ownership

[edit]Donald Gilbert Kennedy, the resident District Officer in the administration of the Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony from 1932 to 1938, described the Pulaka pits as usually being shared between different families, with their total area providing an average of about 40 square yards (36.576 square metres) per head of population, although the area of pits varied from island to island depending on the extent of the freshwater lens that is located under each island.[202] Kennedy also describe the land ownership as having evolved from the pre-European contact system known as Kaitasi (lit. “eat-as-one”), in which the land held by family groups under the control of the senior male member of the clan – a system of land based on kinship-based bonds, which changed over time to become a land ownership system where the land was held by individual owners - known as Vaevae (“to divide”).[202] Under the Vaevae system, a pit may contain numerous small individual holdings with boundaries marked by small stones or with each holding divided by imaginary lines between trees on the edge of the pits. The custom of inheritance of land, and the resolution of disputes over the boundaries of holdings, land ownership and inheritance was traditionally determined by the elders of each island.[202][203]

Tsunami & Cyclones

[edit]The low level of islands makes them very exposed to the effects of a tsunami or cyclone. Nui was struck by a giant wave on 16 February 1882;[204] earthquakes and volcanic eruptions occurring in the basin of the Pacific Ocean – the Pacific Ring of Fire – are possible causes of a tsunami. Tuvalu experienced an average of three tropical cyclones per decade between the 1940s and 1970s, however eight occurred in the 1980s.[205] The impact of individual cyclones is subject to variables including the force of the winds and also whether a cyclone coincides with high tides.

George Westbrook recorded a cyclone that struck Funafuti in 1883.[206] A cyclone struck Nukulaelae on 17–18 March 1886.[206] Captain Edward Davis of HMS Royalist, who visited the Ellice Group in 1892, recorded in the ship's diary that in February 1891 the Ellice Group was devastated by a severe cyclone. A cyclone caused severe damage to the islands in 1894.[207] In 1972 Cyclone Bebe caused severe damage to Funafuti.[208] Cyclone Ofa had a major impact on Tuvalu in late January and early February 1990. During the 1996–97 cyclone season, Cyclone Gavin, Hina and Keli passed through the islands of Tuvalu.[209][210]

Cyclone of 1883

[edit]George Westbrook,[101] a trader on Funafuti, recorded a cyclone that struck on 23–24 December 1883. At the time the cyclone struck he was the sole inhabitant of Funafuti as Tema, the Samoan missionary, had taken everyone else to Funafala to work on erecting a church. The buildings on Funafuti were destroyed, including the church and the trade stores of George Westbrook and Alfred Restieaux. Little damage had occurred at Funafala and the people returned to rebuild at Funafuti.[206][50]

Cyclone Bebe 1972

[edit]

In 1972 Funafuti was in the path of Cyclone Bebe during the 1972–73 South Pacific cyclone season. Cyclone Bebe was a pre-season tropical cyclone that impacted the Gilbert, Ellice Islands, and Fiji island groups.[211] First spotted on 20 October, the system intensified and grew in size through 22 October. At about 4 p.m. on Saturday 21 October sea water was bubbling through the coral on the airfield with the water reaching a height of about 4–5 feet high. Cyclone Bebe continued through Sunday 22 October. The Ellice Islands Colony's ship Moanaraoi was in the lagoon and survived, however 3 tuna boats were wrecked. Waves broke over the atoll. Five people died, two adults and a 3-month-old child were swept away by waves, and two sailors from the tuna boats were drowned.[208] Cyclone Bebe knocked down 95% of the houses and trees.[212] The storm surge created a wall of coral rubble along the ocean side of Funafuti and Funafala that was about 10 miles (16 km) long, and about 10 to 20 feet (3.0 to 6.1 m) thick at the bottom.[208][213][214][215] The cyclone submerged Funafuti and sources of drinking water were contaminated as a result of the system's storm surge and fresh water flooding; with severe damages to houses and installations.[216]

Cyclone Pam 2015

[edit]Prior to the formation of Cyclone Pam, flooding from king tides, which peaked at 3.4 m (11 ft) on 19 February 2015, caused considerable road damage across the multi-island nation of Tuvalu.[217] Between 10 and 11 March, tidal surges estimated to be 3–5 m (9.8–16.4 ft) associated with the cyclone swept across the low-lying islands of Tuvalu. The atolls of Nanumea, Nanumanga, Niutao, Nui, Nukufetau, Nukulaelae, and Vaitupu were affected.[218][219] Significant damage to agriculture and infrastructure occurred.[220] The outermost islands were hardest hit, with one flooded in its entirety.[221] A state of emergency was subsequently declared on 13 March.[222][220] Water supplies on Nui were contaminated by seawater and rendered undrinkable.[218] An estimated 45 percent of the nation's nearly 10,000 people were displaced, according to Prime Minister Enele Sopoaga.[223]

New Zealand started providing aid to Tuvalu on 14 March.[224][225] Owing to the severity of damage in the nation, the local chapter of the Red Cross enacted an emergency operation plan on 16 March which would focus on the needs of 3,000 people. The focus on the 81,873 CHF operation was to provide essential non-food items and shelter.[218] Flights carrying these supplies from Fiji began on 17 March.[219] Prime Minister Sopoaga stated that Tuvalu appeared capable of handling the disaster on its own and urged that international relief be focused on Vanuatu.[219][221] Tuvalu's Disaster Coordinator, Suneo Silu, said the priority island is Nui as sources of fresh water were contaminated.[219] On 17 March, the Taiwanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs announced a donation of US$61,000 in aid to Tuvalu.[226] UNICEF and Australia also delivered aid to Tuvalu.[227][228]

As of 22 March, 71 families (40 percent of the population) of Nui were displaced and were living in 3 evacuation centres or with other families and on Nukufetau, 76 people (13 percent of the population) were displaced and were living in 2 evacuation centres.[229] The Situation Report published on 30 March reported that on Nukufetau all the displaced people had returned to their homes.[230] Nui suffered the most damage of the three central islands (Nui, Nukufetau and Vaitupu);[231] with both Nui and Nukufetau suffering the loss of 90% of the crops.[230] Of the three northern islands (Nanumanga, Niutao, Nanumea), Nanumanga suffered the most damage, with 60–100 houses flooded and damage to the health facility.[230]

Tuvalu and climate change

[edit]Tuvalu became the 189th member of the United Nations in September 2000,[232][233] and appoints a Permanent Representative to the United Nations.

Tuvalu, one of the world's smallest countries, has indicated that its priority within the United Nations is to emphasise "climate change and the unique vulnerabilities of Tuvalu to its adverse impacts". Other priorities are obtaining "additional development assistance from potential donor countries", widening the scope of Tuvalu's bilateral diplomatic relations, and, more generally, expressing "Tuvalu's interests and concerns".[234] The issue of climate change in Tuvalu has featured prominently in Tuvalu's interventions at the UN and at other international fora.

In 2002, Governor-General Tomasi Puapua concluded his address to the United Nations General Assembly by saying:

Finally, Mr. President, efforts to ensure sustainable development, peace, security and longterm livelihood for the world will have no meaning to us in Tuvalu in the absence of serious actions to address the adverse and devastating effects of global warming. At no more than three meters above sea level, Tuvalu is particularly exposed to these effects. Indeed our people are already migrating to escape, and are already suffering from the consequences of what world authorities on climate change have consistently been warning us. Only two weeks ago, a period when the weather was normal and calm and at low tide, unusually big waves suddenly crashed ashore and flooded most part of the capital island. In the event that the situation is not reversed, where does the international community think the Tuvalu people are to hide from the onslaught of sea level rise? Taking us as environmental refugees, is not what Tuvalu is after in the long run. We want the islands of Tuvalu and our nation to remain permanently and not be submerged as a result of greed and uncontrolled consumption of industrialized countries. We want our children to grow up the way my wife and I did in our own islands and in our own culture. We once again appeal to the industrialized countries, particularly those who have not done so, to urgently ratify and fully implement the Kyoto Protocol, and to provide concrete support in all our adaptation efforts to cope with the effects of climate change and sea level rise. Tuvalu, having little or nothing to do with the causes, cannot be left on its own to pay the price. We must work together. May God Bless you all. May God Bless the United Nations.[235]

Addressing the Special Session of the Security Council on Energy, Climate and Security in April 2007, Ambassador Pita stated:

We face many threats associated with climate change. Ocean warming is changing the very nature of our island nation. Slowly our coral reefs are dying through coral bleaching, we are witnessing changes to fish stocks, and we face the increasing threat of more severe cyclones. With the highest point of four metres above sea level, the threat of severe cyclones is extremely disturbing, and severe water shortages will further threaten the livelihoods of people in many islands. Madam President, our livelihood is already threatened by sea level rise, and the implications for our long term security are very disturbing. Many have spoken about the possibility of migrating from our homeland. If this becomes a reality, then we are faced with an unprecedented threat to our nationhood. This would be an infringement on our fundamental rights to nationality and statehood as constituted under the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international conventions.[236]

Addressing the United Nations General Assembly in September 2008, Prime Minister Apisai Ielemia stated:

Climate change is, without doubt, the most serious threat to the global security and survival of mankind. It is an issue of enormous concern to a highly vulnerable small island State like Tuvalu. Here in this Great House, we now know both the science and economics of climate change. We also know the cause of climate change, and that human actions by ALL countries are urgently needed to address it. The central message of both the IPCC reports and the Sir Nicholas Stern reports to us, world leaders, is crystal clear: unless urgent actions are done to curb greenhouses gasses emissions by shifting to a new global energy mix based on renewable energy sources, and unless timely adaptation is done, the adverse impact of climate change on all communities, will be catastrophic.[237] (italics in original submission)

In November 2011, Tuvalu was one of the eight founding members of Polynesian Leaders Group, a regional grouping intended to cooperate on a variety of issues including culture and language, education, responses to climate change, and trade and investment.[238][239] Tuvalu participates in the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS), which is a coalition of small island and low-lying coastal countries that have concerns about their vulnerability to the adverse effects of global climate change. The Sopoaga Ministry led by Enele Sopoaga made a commitment under the Majuro Declaration, which was signed on 5 September 2013, to implement power generation of 100% renewable energy (between 2013 and 2020). This commitment is proposed to be implemented using Solar PV (95% of demand) and biodiesel (5% of demand). The feasibility of wind power generation will be considered as part of the commitment to increase the use of renewable energy in Tuvalu.[240]

In September 2013 Enele Sopoaga said that relocating Tuvaluans to avoid the impact of sea level rise "should never be an option because it is self defeating in itself. For Tuvalu I think we really need to mobilise public opinion in the Pacific as well as in the [rest of] world to really talk to their lawmakers to please have some sort of moral obligation and things like that to do the right thing."[241]

Marshall Islands President Christopher Loeak presented the Majuro Declaration to the UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon during General Assembly Leaders' week from 23 September 2013. The Majuro Declaration is offered as a "Pacific gift" to the UN Secretary-General in order to catalyze more ambitious climate action by world leaders beyond that achieved at the December 2009 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP15). On 29 September 2013 the Deputy Prime Minister Vete Sakaio concluded his speech to the General Debate of the 68th Session of the United Nations General Assembly with an appeal to the world, "please save Tuvalu against climate change. Save Tuvalu in order to save yourself, the world".[242]

Prime Minister Enele Sopoaga said at the 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP21) that the goal for COP21 should a global temperature goal of below 1.5 degrees Celsius relative to pre-industrial levels, which is the position of the Alliance of Small Island States.[243] Prime Minister Sopoaga said in his speech to the meeting of heads of state and government:

Tuvalu's future at current warming, is already bleak, any further temperature increase will spell the total demise of Tuvalu…. For Small Island Developing States, Least Developed Countries and many others, setting a global temperature goal of below 1.5 degrees Celsius relative to pre-industrial levels is critical. I call on the people of Europe to think carefully about their obsession with 2 degrees. Surely, we must aim for the best future we can deliver and not a weak compromise.[244]

His speech concluded with the plea:

Let's do it for Tuvalu. For if we save Tuvalu we save the world.[244]

Enele Sopoaga described the important outcomes of COP21 as including the stand-alone provision for assistance to small island states and some of the least developed countries for loss and damage resulting from climate change and the ambition of limiting temperature rise to 1.5 degrees by the end of the century.[245]

In November 2022, Simon Kofe, Minister for Justice, Communication & Foreign Affairs, proclaimed that in response to rising sea levels and the perceived failures by the outside world to combat global warming, the country would be uploading itself to the metaverse in an effort to preserve itself and allow it to function as a country even in the event of it being underwater.[246]

On 10 November 2023, Tuvalu signed the Falepili Union, a bilateral diplomatic relationship with Australia, under which Australia will provide a pathway for citizens of Tuvalu to migrate to Australia, to enable climate-related mobility for Tuvaluans.[247][248]

Bibliography

[edit]- Bibliography of Tuvalu Archived 24 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine.

Filmography

[edit]Documentary films about Tuvalu:

- Tu Toko Tasi (Stand by Yourself) (2000) Conrad Mill, a Secretariat of the Pacific Community (SPC) production.[249]

- Paradise Domain – Tuvalu (Director: Joost De Haas, Bullfrog Films/TVE 2001) 25:52 minutes – YouTube video.[250]

- Tuvalu island tales (A Tale of two Islands) (Director: Michel Lippitsch) 34 minutes – YouTube video

- The Disappearing of Tuvalu: Trouble in Paradise (2004) by Christopher Horner and Gilliane Le Gallic.[251]

- Paradise Drowned: Tuvalu, the Disappearing Nation (2004) Written and produced by Wayne Tourell. Directed by Mike O'Connor, Savana Jones-Middleton and Wayne Tourell.[252]

- Going Under (2004) by Franny Armstrong, Spanner Films.[250]

- Before the Flood: Tuvalu (2005) by Paul Lindsay (Storyville/BBC Four).[250]

- Time and Tide (2005) by Julie Bayer and Josh Salzman, Wavecrest Films.[253]

- Tuvalu: That Sinking Feeling (2005) by Elizabeth Pollock from PBS Rough Cut

- Atlantis Approaching (2006) by Elizabeth Pollock, Blue Marble Productions.[254]

- King Tide | The Sinking of Tuvalu (2007) by Juriaan Booij.[255]

- Tuvalu (Director: Aaron Smith, 'Hungry Beast' program, ABC June 2011) 6:40 minutes – YouTube video

- Tuvalu: Renewable Energy in the Pacific Islands Series (2012) a production of the Global Environment Facility (GEF), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and SPREP 10 minutes – YouTube video.

- Mission Tuvalu (Missie Tuvalu) (2013) feature documentary directed by Jeroen van den Kroonenberg.[256]

- ThuleTuvalu (2014) by Matthias von Gunten, HesseGreutert Film/OdysseyFilm.[257]

External sources - photographs

[edit]- Andrew, Thomas (1886). "Washing Hole Funafuti. From the album: Views in the Pacific Islands". Collection of Museum of New Zealand (Te Papa). Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- Andrew, Thomas (1886). "Mission House Nui. From the album: Views in the Pacific Islands". Collection of Museum of New Zealand (Te Papa). Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- Andrew, Thomas (1886). "Bread fruit tree Nui. From the album: Views in the Pacific Islands". Collection of Museum of New Zealand (Te Papa). Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- Lambert, Sylvester M. "Young woman, member of the O'Brien family, Funafuti, Tuvalu". Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego. Retrieved 18 November 2017.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Janet Nicoll is the correct spelling of the trading steamer owned by Henderson and Macfarlane of Auckland, New Zealand, which operated between Sydney, Auckland and into the central Pacific. Fanny Vandegrift Stevenson miss-names the ship as the Janet Nicol in her account of the 1890 voyage.

- ^ "On 2 October 1942, a Marine and Naval Task Force from Samoa landed on Funafuti, Ellice Islands. It consisting of the Marine Corps 26th and 27th Provisional Companies X and Y, the 4th Detachment, 2nd Naval Construction Battalion and Naval Administrative Group No. 3 plus the Advance Marine Base Depot formed the post. A few days later Motor Torpedo Squadron 3 (2) began operating from the island...The island was reinforced with the arrival of the 5th Marine Defense Battalion less detachments "A" and "B". The Japanese were unaware that the Americans were positioned on their southern flank until sighted by a passing flying boat in March 1943. By that time United States forces were fully entrenched in the Ellice Islands."[122]