Pottery

Pottery is the process and the products of forming vessels and other objects with clay and other raw materials, which are fired at high temperatures to give them a hard and durable form. The place where such wares are made by a potter is also called a pottery (plural potteries). The definition of pottery, used by the ASTM International, is "all fired ceramic wares that contain clay when formed, except technical, structural, and refractory products".[1] End applications include tableware, decorative ware, sanitary ware, and in technology and industry such as electrical insulators and laboratory ware. In art history and archaeology, especially of ancient and prehistoric periods, pottery often means only vessels, and sculpted figurines of the same material are called terracottas.[2]

Pottery is one of the oldest human inventions, originating before the Neolithic period, with ceramic objects such as the Gravettian culture Venus of Dolní Věstonice figurine discovered in the Czech Republic dating back to 29,000–25,000 BC.[3] However, the earliest known pottery vessels were discovered in Jiangxi, China, which date back to 18,000 BC. Other early Neolithic and pre-Neolithic pottery artifacts have been found, in Jōmon Japan (10,500 BC),[4] the Russian Far East (14,000 BC),[5] Sub-Saharan Africa (9,400 BC),[6] South America (9,000s–7,000s BC),[7] and the Middle East (7,000s–6,000s BC).

Pottery is made by forming a clay body into objects of a desired shape and heating them to high temperatures (600–1600 °C) in a bonfire, pit or kiln, which induces reactions that lead to permanent changes including increasing the strength and rigidity of the object. Much pottery is purely utilitarian, but some can also be regarded as ceramic art. An article can be decorated before or after firing.

Pottery is traditionally divided into three types: earthenware, stoneware and porcelain. All three may be glazed and unglazed. All may also be decorated by various techniques. In many examples the group a piece belongs to is immediately visually apparent, but this is not always the case; for example fritware uses no or little clay, so falls outside these groups. Historic pottery of all these types is often grouped as either "fine" wares, relatively expensive and well-made, and following the aesthetic taste of the culture concerned, or alternatively "coarse", "popular", "folk" or "village" wares, mostly undecorated, or simply so, and often less well-made.

Cooking in pottery became less popular once metal pots became available,[8] but is still used for dishes that benefit from the qualities of pottery cooking, typically slow cooking in an oven, such as biryani, cassoulet, daube, tagine, jollof rice, kedjenou, cazuela and types of baked beans.[8]

Main types

[edit]Earthenware

[edit]

The earliest forms of pottery were made from clays that were fired at low temperatures, initially in pit-fires or in open bonfires. They were hand formed and undecorated. Earthenware can be fired as low as 600 °C, and is normally fired below 1200 °C.[9]

Because unglazed earthenware is porous, it has limited utility for the storage of liquids or as tableware. However, earthenware has had a continuous history from the Neolithic period to today. It can be made from a wide variety of clays, some of which fire to a buff, brown or black colour, with iron in the constituent minerals resulting in a reddish-brown. Reddish coloured varieties are called terracotta, especially when unglazed or used for sculpture. The development of ceramic glaze made impermeable pottery possible, improving the popularity and practicality of pottery vessels. Decoration has evolved and developed through history.

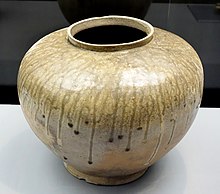

Stoneware

[edit]

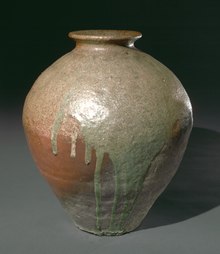

Stoneware is pottery that has been fired in a kiln at a relatively high temperature, from about 1,100 °C to 1,200 °C, and is stronger and non-porous to liquids.[10] The Chinese, who developed stoneware very early on, classify this together with porcelain as high-fired wares. In contrast, stoneware could only be produced in Europe from the late Middle Ages, as European kilns were less efficient, and the right type of clay less common. It remained a speciality of Germany until the Renaissance.[11]

Stoneware is very tough and practical, and much of it has always been utilitarian, for the kitchen or storage rather than the table. But "fine" stoneware has been important in China, Japan and the West, and continues to be made. Many utilitarian types have also come to be appreciated as art.

Porcelain

[edit]

Porcelain is made by heating materials, generally including kaolin, in a kiln to temperatures between 1,200 and 1,400 °C (2,200 and 2,600 °F). This is higher than used for the other types, and achieving these temperatures was a long struggle, as well as realizing what materials were needed. The toughness, strength and translucence of porcelain, relative to other types of pottery, arises mainly from vitrification and the formation of the mineral mullite within the body at these high temperatures.

Although porcelain was first made in China, the Chinese traditionally do not recognise it as a distinct category, grouping it with stoneware as "high-fired" ware, opposed to "low-fired" earthenware. This confuses the issue of when it was first made. A degree of translucency and whiteness was achieved by the Tang dynasty (AD 618–906), and considerable quantities were being exported. The modern level of whiteness was not reached until much later, in the 14th century. Porcelain was also made in Korea and in Japan from the end of the 16th century, after suitable kaolin was located in those countries. It was not made effectively outside East Asia until the 18th century.[12]

Archaeology

[edit]

The study of pottery can help to provide an insight into past cultures. Fabric analysis (see section below), used to analyse the fabric of pottery, is important part of archaeology for understanding the archaeological culture of the excavated site by studying the fabric of artifacts, such as their usage, source material composition, decorative pattern, color of patterns, etc. This helps to understand characteristics, sophistication, habits, technology, tools, trade, etc. of the people who made and used the pottery. Carbon dating reveals the age. Sites with similar pottery characteristics have the same culture, those sites which have distinct cultural characteristics but with some overlap are indicative of cultural exchange such as trade or living in vicinity or continuity of habitation, etc. Examples are black and red ware, redware, Sothi-Siswal culture and Painted Grey Ware culture. The six fabrics of Kalibangan is a good example of use of fabric analysis in identifying a differentiated culture which was earlier thought to be typical Indus Valley civilisation (IVC) culture.

Pottery is durable, and fragments, at least, often survive long after artifacts made from less-durable materials have decayed past recognition. Combined with other evidence, the study of pottery artefacts is helpful in the development of theories on the organisation, economic condition and the cultural development of the societies that produced or acquired pottery. The study of pottery may also allow inferences to be drawn about a culture's daily life, religion, social relationships, attitudes towards neighbours, attitudes to their own world and even the way the culture understood the universe.

It is valuable to look into pottery as an archaeological record of potential interaction between peoples. When pottery is placed within the context of linguistic and migratory patterns, it becomes an even more prevalent category of social artifact.[13] As proposed by Olivier P. Gosselain, it is possible to understand ranges of cross-cultural interaction by looking closely at the chaîne opératoire of ceramic production.[14]

The methods used to produce pottery in early Sub-Saharan Africa are divisible into three categories: techniques visible to the eye (decoration, firing and post-firing techniques), techniques related to the materials (selection or processing of clay, etc.), and techniques of molding or fashioning the clay.[14] These three categories can be used to consider the implications of the reoccurrence of a particular sort of pottery in different areas. Generally, the techniques that are easily visible (the first category of those mentioned above) are thus readily imitated, and may indicate a more distant connection between groups, such as trade in the same market or even relatively close settlements.[14] Techniques that require more studied replication (i.e., the selection of clay and the fashioning of clay) may indicate a closer connection between peoples, as these methods are usually only transmissible between potters and those otherwise directly involved in production.[14] Such a relationship requires the ability of the involved parties to communicate effectively, implying pre-existing norms of contact or a shared language between the two. Thus, the patterns of technical diffusion in pot-making that are visible via archaeological findings also reveal patterns in societal interaction.

Chronologies based on pottery are often essential for dating non-literate cultures and are often of help in the dating of historic cultures as well. Trace-element analysis, mostly by neutron activation, allows the sources of clay to be accurately identified and the thermoluminescence test can be used to provide an estimate of the date of last firing. Examining sherds from prehistory, scientists learned that during high-temperature firing, iron materials in clay record the state of the Earth's magnetic field at that moment.

Fabric analysis

[edit]The "clay body" is also called the "paste" or the "fabric", which consists of 2 things, the "clay matrix" – composed of grains of less than 0.02 mm grains which can be seen using the high-powered microscopes or a scanning electron microscope, and the "clay inclusions" – which are larger grains of clay and could be seen with the naked eye or a low-power binocular microscope. For geologists, fabric analysis means spatial arrangement of minerals in a rock. For Archaeologists, the "fabric analysis" of pottery entails the study of clay matrix and inclusions in the clay body as well as the firing temperature and conditions. Analysis is done to examine the following 3 in detail:[15]

- How pottery was made e.g. material, design such as shape and style, etc.

- Its decorations, such as patterns, colors of patterns, slipped (glazing) or unslipped decoration

- Evidence of type of use.

The Six fabrics of Kalibangan is a good example of fabric analysis.

Clay bodies and raw materials

[edit]

Body, or clay body, is the material used to form pottery. Thus a potter might prepare, or order from a supplier, such an amount of earthenware body, stoneware body or porcelain body. The compositions of clay bodies varies considerably, and include both prepared and 'as dug'; the former being by far the dominant type for studio and industry. The properties also vary considerably, and include plasticity and mechanical strength before firing; the firing temperature needed to mature them; properties after firing, such as permeability, mechanical strength and colour.

There can be regional variations in the properties of raw materials used for pottery, and these can lead to wares that are unique in character to a locality.

The main ingredient of the body is clay. Some different types used for pottery include:[16]

- Kaolin, sometimes referred to as china clay, is a key ingredient in porcelain, which was first used in China around the 7th and 8th centuries.[17]

- Ball clay: An extremely plastic, fine grained sedimentary clay, which may contain some organic matter.

- Fire clay: A clay having a slightly lower percentage of fluxes than kaolin, but usually quite plastic. It is highly heat resistant form of clay which can be combined with other clays to increase the firing temperature and may be used as an ingredient to make stoneware type bodies.

- Stoneware clay: Suitable for creating stoneware. Has many of the characteristics between fire clay and ball clay, having finer grain, like ball clay but is more heat resistant like fire clays.

- Common red clay and shale clay have vegetable and ferric oxide impurities which make them useful for bricks, but are generally unsatisfactory for pottery except under special conditions of a particular deposit.[18]

- Bentonite: An extremely plastic clay which can be added in small quantities to short clay to increase the plasticity.

It is common for clays and other raw materials to be mixed to produce clay bodies suited to specific purposes. Various mineral processing techniques are often utilised before mixing the raw materials, with comminution being effectively universal for non-clay materials.

Examples of non-clay materials include:

- Feldspar, act as fluxes which lower the vitrification temperature of bodies.

- Quartz, an important role is to attenuate drying shrinkage.

- Nepheline syenite, an alternative to feldspar.

- Calcined alumina, can enhance the fired properties of a body.

- Chamotte, also called grog, is fired clay which it is crushed, and sometimes then milled. Helps attenuate drying shrinkage.[19]

- Bone ash, produced by the calcination of animal bone. A key raw material for bone china.

- Frit, produced made by quenching and breaking up a glass of a specific composition. Can be used at low additions in some bodies, but common uses include as components of a glaze or enamel, or for the body of fritware, when it usually mixed with larger quantities of quartz sand.

- Various others at low levels of addition such as dolomite, limestone, talc and wollastonite.

Production

[edit]The production of pottery includes the following stages:

- Preparing the clay body.

- Shaping

- Drying

- Firing

- Glazing and decorating. (this can be undertaken prior to firing. Also, additional firing stages after decoration may be needed.)

Shaping

[edit]Before being shaped, clay must be prepared. This may include kneading to ensure an even moisture content throughout the body. Air trapped within the clay body needs to be removed, or de-aired, and can be accomplished either by a machine called a vacuum pug or manually by wedging. Wedging can also help produce an even moisture content. Once a clay body has been kneaded and de-aired or wedged, it is shaped by a variety of techniques, which include:

- Hand-building: This is the earliest forming method. Wares can be constructed by hand from coils of clay, combining flat slabs of clay, or pinching solid balls of clay or some combination of these. Parts of hand-built vessels are often joined with the aid of slip. Some studio potters find hand-building more conducive for one-of-a-kind works of art.

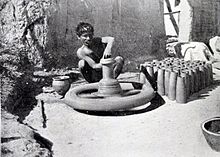

A potter using a potter's wheel describes his materials (in Romanian and English) - The potter's wheel: In a process called "throwing" (coming from the Old English word thrawan which means to twist or turn,[20]) a ball of clay is placed in the centre of a turntable, called the wheel-head, which the potter rotates with a stick, with foot power or with a variable-speed electric motor. During the process of throwing, the wheel rotates while the solid ball of soft clay is pressed, squeezed and pulled gently upwards and outwards into a hollow shape. Skill and experience are required to throw pots of an acceptable standard and, while the ware may have high artistic merit, the reproducibility of the method is poor.[21] Because of its inherent limitations, throwing can only be used to create wares with radial symmetry on a vertical axis.

- Press moulding: a simple technique of shaping by manually pressing a lump of clay body into a porous mould.[22][23][24]

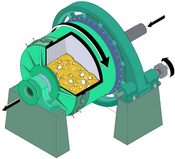

- Granulate pressing: a highly automated technique of shaping by pressing clay body in a semi-dry and granulated form in a mould. The body is pressed into the mould by a porous die through which water is pumped at high pressure. The fine, free flowing granulated body is prepared by spray drying a high-solids content slip. Granulate pressing, also known as dust pressing, is widely used in the manufacture of ceramic tiles and, increasingly, of plates.[25][26][27]

Jiggering a plate - Jiggering and jolleying: These operations are carried out on the potter's wheel and allow the time taken to bring wares to a standardized form to be reduced. Jiggering is the operation of bringing a shaped tool into contact with the plastic clay of a piece under construction, the piece itself being set on a rotating plaster mould on the wheel. The jigger tool shapes one face while the mould shapes the other. Jiggering is used only in the production of flat wares, such as plates, but a similar operation, jolleying, is used in the production of hollow-wares such as cups. Jiggering and jolleying have been used in the production of pottery since at least the 18th century. In large-scale factory production, jiggering and jolleying are usually automated, which allows the operations to be carried out by semi-skilled labour.

- Roller-head machine: This machine is for shaping wares on a rotating mould, as in jiggering and jolleying, but with a rotary shaping tool replacing the fixed profile. The rotary shaping tool is a shallow cone having the same diameter as the ware being formed and shaped to the desired form of the back of the article being made. Wares may in this way be shaped, using relatively unskilled labour, in one operation at a rate of about twelve pieces per minute, though this varies with the size of the articles being produced. Developed in the UK just after World War II by the company Service Engineers, roller-heads were quickly adopted by manufacturers around the world; it remains the dominant method for producing both flatware and holloware, such as plates and mugs.[28]

- Pressure casting: Is a development of traditional slipcasting. Specially developed polymeric materials allow a mould to be subject to application external pressures of up to 4.0 MPa – so much higher than slip casting in plaster moulds where the capillary forces correspond to a pressure of around 0.1–0.2 MPa. The high pressure leads to much faster casting rates and, hence, faster production cycles. Furthermore, the application of high pressure air through the polymeric moulds upon demoulding the cast means a new casting cycle can be started immediately in the same mould, unlike plaster moulds which require lengthy drying times. The polymeric materials have much greater durability than plaster and, therefore, it is possible to achieve shaped products with better dimensional tolerances and much longer mould life. Pressure casting was developed in the 1970s for the production of sanitaryware although, more recently, it has been applied to tableware.[29][30][31][32]

- RAM pressing: This is used to shape ware by pressing a bat of prepared clay body into a required shape between two porous moulding plates. After pressing, compressed air is blown through the porous mould plates to release the shaped wares.[33]

- Slip casting: This is suited to the making of shapes that cannot be formed by other methods. A liquid slip, made by mixing clay body with water, is poured into a highly absorbent plaster mould. Water from the slip is absorbed into the mould leaving a layer of clay body covering its internal surfaces and taking its internal shape. Excess slip is poured out of the mould, which is then split open and the moulded object removed. Slip casting is widely used in the production of sanitaryware and is also used for making other complex shaped ware such as teapots and figurines.

- Injection moulding: This is a shape-forming process adapted for the tableware industry from the method long established for the forming of thermoplastic and some metal components.[34] It has been called Porcelain Injection Moulding, or PIM.[35] Suited to the mass production of complex-shaped articles, one significant advantage of the technique is that it allows the production of a cup, including the handle, in a single process, and thereby eliminates the handle-fixing operation and produces a stronger bond between cup and handle.[36] The feed to the mould die is a mix of approximately 50 to 60 per cent unfired body in powder form, together with 40 to 50 per cent organic additives composed of binders, lubricants and plasticisers.[35] The technique is not as widely used as other shaping methods.[37]

- 3D printing: There are two methods. One involves the layered deposition of soft clay body similar to fused deposition modelling (FDM), and the other uses powder binding techniques where clay body in dry powder form is fused together layer upon layer with a liquid.[38][39]

- Injection moulding of ceramic tableware has been developed, though it has yet to be fully commercialised.[40]

Drying

[edit]Prior to firing, the water in an article needs to be removed. A number of different stages, or conditions of the article, can be identified:

- Greenware refers to unfired objects at any stage of dryness, but is most often used to refer to objects ready to be fired. At sufficient moisture content, bodies at this stage are in their most plastic form (as they are soft and malleable, and hence can be easily deformed by handling). Prior to firing, any state of clay may be hydrated or dehydrated into any other unfired stage.

- Plastic, also known as Wet, refers to clay that is malleable and sufficiently wet to shape by hand or on a potter's wheel, but strong enough to hold its shape. At this stage the clay has between 20% and 25% moisture content.[41] This is the stage most commercial clays are sold at, and at which most of the shaping process is done.

- Leather-hard refers to a clay body that has been dried partially. At this stage the clay object has approximately 15% moisture content. Clay bodies at this stage are very firm and only slightly pliable. Trimming and handle attachment often occurs at the leather-hard state.

- Bone-dry refers to clay bodies when they reach a moisture content at or near 0%. At that moisture content, the item is ready to be fired. Additionally, the piece is extremely brittle at this stage and must be handled with care.[42][43]

Firing

[edit]

Firing produces permanent and irreversible chemical and physical changes in the body. It is only after firing that the article or material is pottery. In lower-fired pottery, the changes include sintering, the fusing together of coarser particles in the body at their points of contact with each other. In the case of porcelain, where higher firing-temperatures are used, the physical, chemical and mineralogical properties of the constituents in the body are greatly altered. In all cases, the reason for firing is to permanently harden the wares, and the firing regime must be appropriate to the materials used.

Temperature

[edit]As a rough guide, modern earthenwares are normally fired at temperatures in the range of about 1,000 °C (1,830 °F) to 1,200 °C (2,190 °F); stonewares at between about 1,100 °C (2,010 °F) to 1,300 °C (2,370 °F); and porcelains at between about 1,200 °C (2,190 °F) to 1,400 °C (2,550 °F). Historically, reaching high temperatures was a long-lasting challenge, and earthenware can be fired effectively as low as 600 °C (1,112 °F), achievable in primitive pit firing. The time spent at any particular temperature is also important, the combination of heat and time is known as heatwork.

Kilns can be monitored by pyrometers, thermocouples and pyrometric devices.

Atmosphere

[edit]

The atmosphere within a kiln during firing can affect the appearance of the body and glaze. Key to this is the differing colours of the various oxides of iron, such as iron(III) oxide (also known as ferric oxide or Fe2O3) which is associated with brown-red colours, whilst iron(II) oxide (also known as ferrous oxide or FeO) is associated with much darker colours, including black. The oxygen concentration in the kiln influences the type, and relative proportions, of these iron oxides in fired the body and glaze: for example, where there is a lack of oxygen during firing the associated carbon monoxide (CO) will readily react with oxygen in Fe2O3 in the raw materials and cause it to be reduced to FeO.[44][45]

An oxygen deficient condition, called a reducing atmosphere, is generated by preventing the complete combustion of the kiln fuel; this is achieved by deliberately restricting the supply of air or by supplying an excess of fuel.[44][45]

Methods

[edit]Firing pottery can be done using a variety of methods, with a kiln being the usual firing method. Both the maximum temperature and the duration of firing influences the final characteristics of the ceramic. Thus, the maximum temperature within a kiln is often held constant for a period of time to soak the wares to produce the maturity required in the body of the wares.

Kilns may be heated by burning combustible materials, such as wood, coal and gas, or by electricity. The use of microwave energy has been investigated.[46]

When used as fuels, coal and wood can introduce smoke, soot and ash into the kiln which can affect the appearance of unprotected wares. For this reason, wares fired in wood- or coal-fired kilns are often placed in the kiln in saggars, ceramic boxes, to protect them. Modern kilns fuelled by gas or electricity are cleaner and more easily controlled than older wood- or coal-fired kilns and often allow shorter firing times to be used.

Niche techniques include:

- In a Western adaptation of traditional Japanese Raku ware firing, wares are removed from the kiln while hot and smothered in ashes, paper or woodchips which produces a distinctive carbonised appearance. This technique is also used in Malaysia in creating traditional labu sayung.[47][48]

- In Mali, a firing mound is used rather than a brick or stone kiln. Unfired pots are first brought to the place where a mound will be built, customarily by the women and girls of the village. The mound's foundation is made by placing sticks on the ground, then:

[...] pots are positioned on and amid the branches and then grass is piled high to complete the mound. Although the mound contains the pots of many women, who are related through their husbands' extended families, each women is responsible for her own or her immediate family's pots within the mound. When a mound is completed and the ground around has been swept clean of residual combustible material, a senior potter lights the fire. A handful of grass is lit and the woman runs around the circumference of the mound touching the burning torch to the dried grass. Some mounds are still being constructed as others are already burning.[49]

Stages

[edit]- Biscuit (or bisque)[50][51] refers to the clay after the object is shaped to the desired form and fired in the kiln for the first time, known as "bisque fired" or "biscuit fired". This firing results in both chemical and physical changes to the minerals of the clay body.

- Glaze fired is the final stage of some pottery making, or glost fired.[21] A glaze may be applied to the biscuit ware and the object can be decorated in several ways. After this the object is "glazed fired", which causes the glaze material to melt, then adhere to the object. Depending on the temperature schedule the glaze firing may also further mature the body as chemical and physical changes continue.

Decorating

[edit]Pottery may be decorated in many different ways. Some decoration can be done before or after the firing, and may be undertaken before or after glazing.

Methods

[edit]

- Painting has been used since early prehistoric times, and can be very elaborate. The painting is often applied to pottery that has been fired once, and may then be overlaid with a glaze afterwards. Many pigments change colour when fired, and the painter must allow for this.

- Glaze: Perhaps the most common form of decoration, that also serves as protection to the pottery, by being tougher and keeping liquid from penetrating the pottery. Glaze may be colourless, especially over painting, or coloured and opaque.

- Crystalline glaze: acharacterised by crystalline clusters of various shapes and colours embedded in a more uniform and opaque glaze. Produced by the slow cooling of the glost fire.

- Carving: Pottery vessels may be decorated by shallow carving of the clay body, typically with a knife or similar instrument used on the wheel. This is common in Chinese porcelain of the classic periods.

- Burnishing: The surface of pottery wares may be burnished prior to firing by rubbing with a suitable instrument of wood, steel or stone to produce a polished finish that survives firing. It is possible to produce very highly polished wares when fine clays are used or when the polishing is carried out on wares that have been partially dried and contain little water, though wares in this condition are extremely fragile and the risk of breakage is high.

- Terra Sigillata is an ancient form of decorating ceramics that was first developed in Ancient Greece.

- Lithography, also called litho, although the alternative names of transfer print or "decal" are also common. These are used to apply designs to articles. The litho comprises three layers: the colour, or image, layer which comprises the decorative design; the cover coat, a clear protective layer, which may incorporate a low-melting glass; and the backing paper on which the design is printed by screen printing or lithography. There are various methods of transferring the design while removing the backing-paper, some of which are suited to machine application.

- Banding is the application by hand or by machine of a band of colour to the edge of a plate or cup. Also known as "lining", this operation is often carried out on a potter's wheel.

- Agateware: named after its resemblance to the mineral agate, is produced by partially blending clays of differing colours. In Japan the term "neriage" is used, whilst in China, where such things have been made since at least the Tang dynasty, they are called "marbled" wares.

- Engobe: a clay slip is used to coat the surface of pottery, usually before firing. Its purpose is often decorative though it can also be used to mask undesirable features in the clay to which it is applied. The engobe may be applied by painting or by dipping to provide a uniform, smooth, coating. Such decoration is characteristic of slipware. For sgraffito decoration a layer of engobe is scratched through to reveal the underlying clay.

- Gold: Decoration with gold is used on some high quality ware. Different methods exist for its application, including:

- Best gold – a suspension of gold powder in essential oils mixed with a flux and a mercury salt extended. This can be applied by a painting technique. From the kiln, the decoration is dull and requires burnishing to reveal the full colour

- Acid Gold – a form of gold decoration developed in the early 1860s at the English factory of Mintons Ltd. The glazed surface is etched with diluted hydrofluoric acid prior to application of the gold. The process demands great skill and is used for the decoration only of ware of the highest class.

- Bright Gold – consists of a solution of gold sulphoresinate together with other metal resonates and a flux. The name derives from the appearance of the decoration immediately after removal from the kiln as it requires no burnishing

- Mussel Gold – an old method of gold decoration. It was made by rubbing together gold leaf, sugar and salt, followed by washing to remove solubles

- Underglaze decoration is applied, by a number of techniques, onto ware before it is glazed, an example is blue and white wares. Can be applied by a number of techniques.

- In-glaze decoration, is applied on the surface of the glaze before the glost firing.

- On-glaze decoration is applied on top of the already fired, glazed surface, and then fixed in a second firing at a relatively low temperature.

Glazing

[edit]

Glaze is a glassy coating on pottery, and reasons to use it include decoration, ensuring the item is impermeable to liquids, and minimizing the adherence of pollutants.

Glaze may be applied by spraying, dipping, trailing or brushing on an aqueous suspension of the unfired glaze. The colour of a glaze after it has been fired may be significantly different from before firing. To prevent glazed wares sticking to kiln furniture during firing, either a small part of the object being fired (for example, the foot) is left unglazed or, alternatively, special refractory "spurs" are used as supports. These are removed and discarded after the firing.

Some specialised glazing techniques include:

- Salt-glazing – common salt is introduced to the kiln during the firing process. The high temperatures cause the salt to volatilise, depositing it on the surface of the ware to react with the body to form a sodium aluminosilicate glaze. In the 17th and 18th centuries, salt-glazing was used in the manufacture of domestic pottery. Now, except for use by some studio potters, the process is obsolete. The last large-scale application before its demise in the face of environmental clean air restrictions was in the production of salt-glazed sewer-pipes.[52][53]

- Ash glazing – ash from the combustion of plant matter has been used as the flux component of glazes. The source of the ash was generally the combustion waste from the fuelling of kilns although the potential of ash derived from arable crop wastes has been investigated.[54] Ash glazes are of historical interest in the Far East although there are reports of small-scale use in other locations such as the Catawba Valley Pottery in the United States. They are now limited to small numbers of studio potters who value the unpredictability arising from the variable nature of the raw material.[55]

Health and environmental issues

[edit]Although many of the environmental effects of pottery production have existed for millennia, some of these have been amplified with modern technology and scales of production. The principal factors for consideration fall into two categories:

- Effects on workers: Notable risks include silicosis, heavy metal poisoning, poor indoor air quality, dangerous sound levels and possible over-illumination.

- Effects on the general environment.

Historically, lead poisoning (plumbism) was a significant health concern to those glazing pottery. This was recognised at least as early as the nineteenth century. The first legislation in the UK to limit pottery workers exposure to lead was included in the Factories Act Extension Act in 1864, with further introduced in 1899.[56][57]

Silicosis is an occupational lung disease caused by inhaling large amounts of crystalline silica dust, usually over many years. Workers in the ceramic industry can develop it due to exposure to silica dust in the raw materials; colloquially it has been known as 'Potter's rot'. Less than 10 years after its introduction, in 1720, as a raw material to the British ceramics industry the negative effects of calcined flint on the lungs of workers had been noted.[58] In one study reported in 2022, of 106 UK pottery workers 55 per cent had at least some stage of silicosis.[59][60][61] Exposure to siliceous dusts is reduced by either processing and using the source materials as aqueous suspension or as damp solids, or by the use of dust control measures such as Local exhaust ventilation. These have been mandated by legislation, such as The Pottery (Health and Welfare) Special Regulations 1950.[62][63] The Health and Safety Executive in the UK has produced guidelines on controlling exposure to respirable crystalline silica in potteries, and the British Ceramics Federation provide, as a free download, a guidance booklet. Archived 2023-04-19 at the Wayback Machine

Environmental concerns include off-site water pollution, air pollution, disposal of hazardous materials, disposal of rejected ware and fuel consumption.[64]

History

[edit]A great part of the history of pottery is prehistoric, part of past pre-literate cultures. Therefore, much of this history can only be found among the artifacts of archaeology. Because pottery is so durable, pottery and shards of pottery survive for millennia at archaeological sites, and are typically the most common and important type of artifact to survive. Many prehistoric cultures are named after the pottery that is the easiest way to identify their sites, and archaeologists develop the ability to recognise different types from the chemistry of small shards.

Before pottery becomes part of a culture, several conditions must generally be met.

- First, there must be usable clay available. Archaeological sites where the earliest pottery was found were near deposits of readily available clay that could be properly shaped and fired. China has large deposits of a variety of clay, which gave them an advantage in early development of fine pottery. Many countries have large deposits of a variety of clay.

- Second, it must be possible to heat the pottery to temperatures that will achieve the transformation from raw clay to ceramic. Methods to reliably create fires hot enough to fire pottery did not develop until late in the development of cultures.

- Third, the potter must have time available to prepare, shape and fire the clay into pottery. Even after control of fire was achieved, humans did not seem to develop pottery until a sedentary life was achieved. It has been hypothesized that pottery was developed only after humans established agriculture, which led to permanent settlements. However, the oldest known pottery is from the Czech Republic and dates to 28,000 BC, at the height of the most recent ice age, long before the beginnings of agriculture.

- Fourth, there must be a sufficient need for pottery in order to justify the resources required for its production.[65]

Early pottery

- Methods of forming: Hand-shaping was the earliest method used to form vessels. This included the combination of pinching and coiling.

- Firing: The earliest method for firing pottery wares was the use of bonfires pit fired pottery. Firing times might be short but the peak-temperatures achieved in the fire could be high, perhaps in the region of 900 °C (1,650 °F), and were reached very quickly.[66]

- Clay: Early potters used whatever clay was available to them in their geographic vicinity. However, the lowest quality common red clay was adequate for low-temperature fires used for the earliest pots. Clay tempered with sand, grit, crushed shell or crushed pottery were often used to make bonfire-fired ceramics because they provided an open-body texture that allowed water and volatile components of the clay to escape freely. The coarser particles in the clay also acted to restrain shrinkage during drying, and hence reduce the risk of cracking.

- Form: In the main, early bonfire-fired wares were made with rounded bottoms to avoid sharp angles that might be susceptible to cracking.

- Glazing: the earliest pots were not glazed.

- The potter's wheel was invented in Europe in the 5th millennium BC, and revolutionised pottery production. Earliest potter's wheel dated to the middle of the 5th millennium BC from the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture in western Ukraine.[67]

- Moulds were used to a limited extent as early as the 5th and 6th century BC by the Etruscans[68] and more extensively by the Romans.[69]

- Slipcasting, a popular method for shaping irregular shaped articles. It was first practised, to a limited extent, in China as early as the Tang dynasty.[70]

- Transition to kilns: The earliest intentionally constructed were pit-kilns or trench-kilns, holes dug in the ground and covered with fuel. Holes in the ground provided insulation and resulted in better control over firing.[71]

- Kilns: Pit fire methods were adequate for simple earthenware, but other pottery types needed more sophisticated kilns.

History by region

[edit]Beginnings of pottery

[edit]

Pottery may well have been discovered independently in various places, probably by accidentally creating it at the bottom of fires on a clay soil. The earliest-known ceramic objects are Gravettian figurines such as those discovered at Dolní Věstonice in the modern-day Czech Republic. The Venus of Dolní Věstonice is a Venus figurine, a statuette of a nude female figure dated to 29,000–25,000 BC (Gravettian industry).[3] But there is no evidence of pottery vessels from this period. Weights for looms or fishing-nets are a very common use for the earliest pottery. Sherds have been found in China and Japan from a period between 12,000 and perhaps as long as 18,000 years ago.[5][74] As of 2012, the earliest pottery vessels found anywhere in the world,[75] dating to 20,000 to 19,000 years before the present, was found at Xianren Cave in the Jiangxi province of China.[76][77]

Other early pottery vessels include those excavated from the Yuchanyan Cave in southern China, dated from 16,000 BC,[74] and those found in the Amur River basin in the Russian Far East, dated from 14,000 BC.[5][78]

The Odai Yamamoto I site, belonging to the Jōmon period, currently has the oldest pottery in Japan. Excavations in 1998 uncovered earthenware fragments which have been dated as early as 14,500 BC.[79] The term "Jōmon" means "cord-marked" in Japanese. This refers to the markings made on the vessels and figures using sticks with cords during their production. Recent research has elucidated how Jōmon pottery was used by its creators.[80]

It appears that pottery was independently developed in Sub-Saharan Africa during the 10th millennium BC, with findings dating to at least 9,400 BC from central Mali,[6] and in South America during the 9,000s–7,000s BC.[81][7] The Malian finds date to the same period as similar finds from East Asia – the triangle between Siberia, China and Japan – and are associated in both regions to the same climatic changes (at the end of the ice age new grassland develops, enabling hunter-gatherers to expand their habitat), met independently by both cultures with similar developments: the creation of pottery for the storage of wild cereals (pearl millet), and that of small arrowheads for hunting small game typical of grassland.[6] Alternatively, the creation of pottery in the case of the Incipient Jōmon civilisation could be due to the intensive exploitation of freshwater and marine organisms by late glacial foragers, who started developing ceramic containers for their catch.[80]

East Asia

[edit]

In Japan, the Jōmon period has a long history of development of Jōmon pottery which was characterized by impressions of rope on the surface of the pottery created by pressing rope into the clay before firing. Glazed Stoneware was being created as early as the 15th century BC in China. A form of Chinese porcelain became a significant Chinese export from the Tang dynasty (AD 618–906) onwards.[10] Korean potters adopted porcelain as early as the 14th century AD.[82] The ceramic industry has developed greatly since the Goryeo dynasty, and Goryeo ware, a celadon with unique inlaying techniques, was produced. Later, when white porcelain became common and celadon fell, they created unique ceramics such as Buncheong. Japan's white porcelain was influenced by potters kidnapped during the Japanese invasions of Korea (1592–1598), called The Ceramic Wars, and Japanese engineers introduced it during the Fall of the Ming dynasty's. Typically, Korean potters who settled in Arita pass on pottery techniques, Shonzui Goradoyu-go brought back the secret of its manufacture from the Chinese kilns at Jingdezhen.[83]

In contrast to Europe, the Chinese social elite used pottery extensively at table, for religious purposes, and for decoration, and the standards of fine pottery were very high. From the Song dynasty (960–1279) for several centuries, the tastes of Chinese elites favoured plain-coloured and exquisitely formed pieces; during this period porcelain was perfected in Ding ware, although it was the only one of the Five Great Kilns of the Song period to use it. The traditional Chinese category of high-fired wares includes stoneware types such as Ru ware, Longquan celadon and Guan ware. Painted wares such as Cizhou ware had a lower status, though they were acceptable for making pillows.

The arrival of Chinese blue and white porcelain was probably a product of the Mongol Yuan dynasty (1271–1368) dispersing artists and craftsmen across its large empire. Both the cobalt stains used for the blue colour, and the style of painted decoration, usually based on plant shapes, were initially borrowed from the Islamic world, which the Mongols had also conquered. At the same time Jingdezhen porcelain, produced in Imperial factories, took the undisputed leading role in production. The new elaborately painted style was now favoured at court, and gradually more colours were added.

The secret of making such porcelain was sought in the Islamic world and later in Europe when examples were imported from the East. Many attempts were made to imitate it in Italy and France. However it was not produced outside of East Asia until 1709 in Germany.[84]

South Asia

[edit]

Cord-Impressed style pottery belongs to "Mesolithic" ceramic tradition that developed among Vindhya hunter-gatherers in Central India during the Mesolithic period.[85][86] This ceramic style is also found in later Proto-Neolithic phase in nearby regions.[87] This early type of pottery, also found at the site of Lahuradewa, is currently the oldest known pottery tradition in South Asia, dating back to 7,000–6,000 BC.[88][89][90][91] Wheel-made pottery began to be made during the Mehrgarh Period II (5,500–4,800 BC) and Merhgarh Period III (4,800–3,500 BC), known as the ceramic Neolithic and chalcolithic. Pottery, including items known as the ed-Dur vessels, originated in regions of the Saraswati River / Indus River and have been found in a number of sites in the Indus Civilization.[92][93] Despite an extensive prehistoric record of pottery, including painted wares, little "fine" or luxury pottery was made in the subcontinent in historic times. Hinduism discourages eating off pottery, which probably largely accounts for this. Most traditional Indian pottery vessels are large pots or jars for storage, or small cups or lamps, occasionally treated as disposable. In contrast there are long traditions of sculpted figures, often rather large, in terracotta; this continues with the Bankura horses in Panchmura, West Bengal.

Southeast Asia

[edit]

Pottery in Southeast Asia is as diverse as its ethnic groups. Each ethnic group has their own set of standards when it comes to pottery arts. Potteries are made due to various reasons, such as trade, food and beverage storage, kitchen usage, religious ceremonies, and burial purposes.[94][95][96][97]

West Asia

[edit]Around 8000 BC during the Pre-pottery Neolithic period, and before the invention of pottery, several early settlements became experts in crafting beautiful and highly sophisticated containers from stone, using materials such as alabaster or granite, and employing sand to shape and polish. Artisans used the veins in the material to maximum visual effect. Such objects have been found in abundance on the upper Euphrates river, in what is today eastern Syria, especially at the site of Bouqras.[98]

The earliest history of pottery production in the Fertile Crescent starts the Pottery Neolithic and can be divided into four periods, namely: the Hassuna period (7000–6500 BC), the Halaf period (6500–5500 BC), the Ubaid period (5500–4000 BC), and the Uruk period (4000–3100 BC). By about 5000 BC pottery-making was becoming widespread across the region, and spreading out from it to neighbouring areas.

Pottery making began in the 7th millennium BC. The earliest forms, which were found at the Hassuna site, were hand formed from slabs, undecorated, unglazed low-fired pots made from reddish-brown clays.[71] Within the next millennium, wares were decorated with elaborate painted designs and natural forms, incising and burnished.

The invention of the potter's wheel in Mesopotamia sometime between 6,000 and 4,000 BC (Ubaid period) revolutionised pottery production. Newer kiln designs could fire wares to 1,050 °C (1,920 °F) to 1,200 °C (2,190 °F) which enabled increased possibilities. Production was now carried out by small groups of potters for small cities, rather than individuals making wares for a family. The shapes and range of uses for ceramics and pottery expanded beyond simple vessels to store and carry to specialized cooking utensils, pot stands and rat traps.[99] As the region developed new organizations and political forms, pottery became more elaborate and varied. Some wares were made using moulds, allowing for increased production for the needs of the growing populations. Glazing was commonly used and pottery was more decorated.[100]

In the Chalcolithic period in Mesopotamia, Halafian pottery achieved a level of technical competence and sophistication, not seen until the later developments of Greek pottery with Corinthian and Attic ware.

Europe

[edit]

Europe's oldest pottery, dating from circa 6700 BC, was found on the banks of the Samara River in the middle Volga region of Russia.[101] These sites are known as the Yelshanka culture.

The early inhabitants of Europe developed pottery in the Linear Pottery culture slightly later than the Near East, circa 5500–4500 BC. In the ancient Western Mediterranean elaborately painted earthenware reached very high levels of artistic achievement in the Greek world; there are large numbers of survivals from tombs. Minoan pottery was characterized by complex painted decoration with natural themes.[102] The classical Greek culture began to emerge around 1000 BC featuring a variety of well crafted pottery which now included the human form as a decorating motif. The pottery wheel was now in regular use. Although glazing was known to these potters, it was not widely used. Instead, a more porous clay slip was used for decoration. A wide range of shapes for different uses developed early and remained essentially unchanged during Greek history.[103]

Fine Etruscan pottery was heavily influenced by Greek pottery and often imported Greek potters and painters. Ancient Roman pottery made much less use of painting, but used moulded decoration, allowing industrialized production on a huge scale. Much of the so-called red Samian ware of the Early Roman Empire was produced in modern Germany and France, where entrepreneurs established large potteries. Excavations at Augusta Raurica, near Basel, Switzerland, have revealed a pottery production site in use from the 1st to the 4th century AD.[104]

Pottery was hardly seen on the tables of elites from Hellenistic times until the Renaissance, and most medieval wares were coarse and utilitarian, as the elites ate off metal vessels. Painted Hispano-Moresque ware from Spain, developing the styles of Al-Andalus, became a luxury for late medieval elites, and was adapted in Italy into maiolica in the Italian Renaissance. Both of these were faience or tin-glazed earthenware, and fine faience continued to be made until around 1800 in various countries, especially France, with Nevers faience and several other centres. In the 17th century, imports of Chinese export porcelain and its Japanese equivalent raised the market expectations of fine pottery, and European manufacturers eventually learned to make porcelain, often in the form of soft-paste porcelain, and from the 18th century European porcelain and other wares from a great number of producers became extremely popular, reducing Asian imports.

United Kingdom

[edit]

The city of Stoke-on-Trent is widely known as "The Potteries" because of the large number of pottery factories or, colloquially, "Pot Banks". It was one of the first industrial cities of the modern era where, as early as 1785, two hundred pottery manufacturers employed 20,000 workers.[105][106] Josiah Wedgwood (1730–1795) was the dominant leader.[107]

In North Staffordshire hundreds of companies produced all kinds of pottery, from tablewares and decorative pieces to industrial items. The main pottery types of earthenware, stoneware and porcelain were all made in large quantities, and the Staffordshire industry was a major innovator in developing new varieties of ceramic bodies such as bone china and jasperware, as well as pioneering transfer printing and other glazing and decorating techniques. In general Staffordshire was strongest in the middle and low price ranges, though the finest and most expensive types of wares were also made.[108]

By the late 18th century North Staffordshire was the largest producer of ceramics in the UK, despite significant hubs elsewhere. Large export markets took Staffordshire pottery around the world, especially in the 19th century.[109] Production had begun to decline in the late 19th century, as other countries developed their industries, and declined notably after World War II. Employment fell from 45,000 in 1975 to 23,000 in 1991, and 13,000 in 2002.[110]

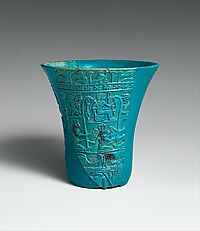

Arabic pottery

[edit]Early Islamic pottery followed the forms of the regions which the Arabs conquered. Eventually, however, there was cross-fertilization between the regions. This was most notable in the Chinese influences on Islamic pottery. Trade between China and Islam took place via the system of trading posts over the lengthy Silk Road. Middle Eastern nations imported stoneware and later porcelain from China. China imported the minerals for Cobalt blue from the Islamic ruled Persia to decorate their blue and white porcelain, which they then exported to the Islamic world.

Likewise, Arabic art contributed to a lasting pottery form identified as Hispano-Moresque in Andalucia. Unique Islamic forms were also developed, including fritware, lusterware and specialized glazes like tin-glazing, which led to the development of the popular maiolica.[111]

One major emphasis in ceramic development in the Muslim world was the use of tile and decorative tilework.

-

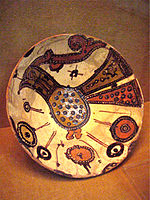

Bowl painted on slip under transparent glaze (polychrome), 9th or 10th century, Nishapur. National Museum of Iran

-

Persian mina'i ware bowl with couple in a garden, around 1200. These wares are the first to use overglaze enamel decoration.

-

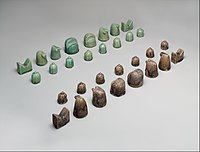

Chess set (Shatrang); Gaming pieces. 12th century, Nishapur glazed fritware. Metropolitan Museum of Art

Americas

[edit]

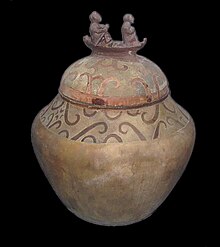

Most evidence points to an independent development of pottery in the Native American cultures, with the earliest known dates from Brazil, from 9,500 to 5,000 years ago and 7,000 to 6,000 years ago.[7] Further north in Mesoamerica, dates begin with the Archaic Era (3500–2000 BC), and into the Formative period (2000 BC – AD 200). These cultures did not develop the stoneware, porcelain or glazes found in the Old World. Maya ceramics include finely painted vessels, usually beakers, with elaborate scenes with several figures and texts. Several cultures, beginning with the Olmec, made terracotta sculpture, and sculptural pieces of humans or animals that are also vessels are produced in many places, with Moche portrait vessels among the finest.

Africa

[edit]

The oldest pottery in the world outside of east Asia can be found in Africa. In 2007, Swiss archaeologists discovered pieces of some of the oldest pottery in Africa at Ounjougou in the central region of Mali, dating to at least 9,400 BC.[6] Excavations in the Bosumpra Cave on the Kwahu Plateau in southeastern Ghana, have revealed well-manufactured pottery decorated with channelling and impressed peigne fileté rigide dating from the early tenth millennium cal. BC.[112] Following the emergence of pottery traditions in the Ounjougou region of Mali around 11,900 BP and in the Bosumpra region of Ghana soon after, ceramics later arrived in the Iho Eleru region of Nigeria.[113] In later periods, a relationship of the introduction of pot-making in some parts of Sub-Saharan Africa with the spread of Bantu languages has been long recognized, although the details remain controversial and awaiting further research, and no consensus has been reached.[13]

Oceania

[edit]Polynesia, Melanesia and Micronesia

Pottery has been found in archaeological sites across the islands of Oceania. It is attributed to an ancient archaeological culture called the Lapita. Another form of pottery called Plainware is found throughout sites of Oceania. The relationship between Lapita pottery and Plainware is not altogether clear.

The Indigenous Australians never developed pottery.[114] After Europeans came to Australia and settled, they found deposits of clay which were analysed by English potters as excellent for making pottery. Less than 20 years later, Europeans came to Australia and began creating pottery. Since then, ceramic manufacturing, mass-produced pottery and studio pottery have flourished in Australia.[115]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ 'Standard Terminology Of Ceramic Whitewares And Related Products.' ASTM C 242–01 (2007.) ASTM International.

- ^ "terracottas (sculptural works)", Getty Art & Architecture Thesaurus

- ^ a b Lienhard, John H. (November 24, 1989). "No. 359: The Dolni Vestonice Ceramics". The Engines of Our Ingenuity. University of Houston. Archived from the original on January 9, 2010. Retrieved September 4, 2010.

- ^ Diamond, Jared (June 1998). "Japanese Roots". Discover. Discover Media LLC. Archived from the original on 2010-03-11. Retrieved 2010-07-10.

- ^ a b c 'AMS 14C Age Of The Earliest Pottery From The Russian Far East; 1996–2002.' Derevianko A.P., Kuzmin Y.V., Burr G.S., Jull A.J.T., Kim J.C. Nuclear Instruments And Methods In Physics Research. B223–224 (2004) 735–39.

- ^ a b c d Simon Bradley, A Swiss-led team of archaeologists has discovered pieces of the oldest African pottery in central Mali, dating back to at least 9,400BC Archived 2012-03-06 at the Wayback Machine, SWI swissinfo.ch – the international service of the Swiss Broadcasting Corporation (SBC), 18 January 2007

- ^ a b c Roosevelt, Anna C. (1996). "The Maritime, Highland, Forest Dynamic and the Origins of Complex Culture". In Frank Salomon; Stuart B. Schwartz (eds.). The Cambridge History of the Native Peoples of the Americas. Cambridge, England New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 264–349. ISBN 978-0-521-63075-7. Archived from the original on 2019-12-07. Retrieved 2019-10-17.

- ^ a b Heck, Mary-Frances. "The Food & Wine Guide to Clay Pot Cooking". Food & Wine. Retrieved 2022-01-26.

- ^ "Art & Architecture Thesaurus Full Record Display (Getty Research)". Getty.edu. Archived from the original on 22 December 2017. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- ^ a b Cooper (2010), p. 54

- ^ Crabtree, Pamela, ed., Medieval Archaeology, Routledge Encyclopedias of the Middle Ages, 2013, Routledge, ISBN 1-135-58298-X, 9781135582982, google books Archived 2018-10-10 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Cooper (2010), pp. 72–79, 160–79

- ^ a b See Bostoen, Koen (2007), "Pots, Words and the Bantu Problem: On Lexical Reconstruction and Early African History", The Journal of African History, 48 (2): 173–199, doi:10.1017/S002185370700254X, hdl:1854/LU-446281, JSTOR 4501038, S2CID 31956178 for a recent discussion of the issues, and links to further literature.

- ^ a b c d See Gosselain, Olivier P. (2000), "Materializing Identities: An African Perspective", Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, 7 (3): 187–217, doi:10.1023/A:1026558503986, JSTOR 20177420, S2CID 140312489 for further discussion and sources.

- ^ Fabric Analysis Archived 2021-07-11 at the Wayback Machine, cambridge.org, accessed 10 July 021.

- ^ Ruth M. Home, "Ceramics for the Potter", Chas. A. Bennett Co., 1952

- ^ "China Clay". www.thepotteries.org. Retrieved 2024-10-01.

- ^ Home, 1952, p. 16

- ^ Whitewares: Production, Testing And Quality Control. Ryan w. & Radford C. Pergamon Press. 1987

- ^ "Why On Earth Do They Call It Throwing? | Contractor Quotes". June 12, 2019. Archived from the original on February 3, 2007.

- ^ a b "Whitewares: Production, Testing And Quality Control." W.Ryan & C.Radford. Pergamon Press. 1987

- ^ Two Centuries of Hellenistic Pottery Homer A. Thompson. Vol. 3, No. 4, The American Excavations in the Athenian Agora: Fifth Report (1934), pp. 311-476. The American School of Classical Studies at Athens

- ^ New Zealand Potter. Vol. 30 No. 1 1988, pp. 7

- ^ Forming Techniques - for the Self-Reliant Potter. Henrik Norsker, James Danisch. Vieweg+1991.Teubner Verlag Wiesbaden

- ^ Using Polymers as a Binder for Improvement of Mechanical Strength of Tableware in Isostatics Press Technology. A. Arasteh Nodeh. Iranian Chemical Engineering Journal – Vol.9 - No. 48 (2010)

- ^ Control And Automation In The Ceramic Industry Evolution. José Gustavo Mallol Gasch. Ceramic Forum International. December 2007 84 (12):E55-E57

- ^ Reference Document On Best Available Techniques In The Ceramic Manufacturing Industry. European Commission August 2007

- ^ An Introduction To The Technology Of Pottery. Paul Rado. Pergamon Press. 1969

- ^ 'Sanitaryware Technology'. Domenico Fortuna. Gruppo Editoriale Faenza Editrice S.p.A. 2000.

- ^ "DGM-E.pdf" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-09-04.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Ceramicindustry.com". Ceramic industries.com. 2000-11-21. Archived from the original on 2011-07-08. Retrieved 2010-09-04.

- ^ Dictionary Of Ceramics. Arthur Dodd & David Murfin. 3rd edition. The Institute Of Minerals. 1994.

- ^ Operations Optimization Of RAM Press Machine By Frame Assembly Techniques. Pairoj Bootpeng, Yuttapong Naksopon, Nuttawut Pebkhuntod, Pattana Charuenying, And Pakawadee Sirilar. Suranaree J. Sci. Technol. 21(2):105-109

- ^ "Novel Approach To Injection Moulding." M.Y.Anwar, P.F. Messer, H.A. Davies, B. Ellis. Ceramic Technology International 1996. Sterling Publications Ltd., London, 1995. pp. 95–96, 98.

- ^ a b "Injection Moulding Of Porcelain Pieces." A. Odriozola, M.Gutierrez, U.Haupt, A.Centeno. Bol. Soc. Esp. Ceram. Vidrio 35, No. 2, 1996. pp. 103–07

- ^ "Injection Moulding Of Cups With Handles." U.Haupt. International Ceramics. No. 2, 1998, pp. 48–51.

- ^ "Injection Moulding Technology In Tableware Production." Ceramic World Review. 13, No. 54, 2003. pp. 94, 96–97.

- ^ Research on The Application of Ceramic 3D Printing Technology. Bin Zhao. March 2021 Journal of Physics Conference Series 1827(1):012057

- ^ From Control To Uncertainty In 3d Printing With Clay. Benay Gürsoy. Computing For A Better Tomorrow. Education And Research In Computer Aided Architectural Design In Europe. Pp. 21-30. 2018

- ^ 'The Application Of Injection Moulding Technology In Modern Tableware Production. 'P. Quirmbach, S. Schwartz, F. Magerl. Ceramic Forum International 81(3):E24-E31, 2004

- ^ "Quick Tip: Reconstituting Clay". Default. Retrieved 2024-10-01.

- ^ Kim (2012-04-02). "Need to know: Stages of drying in clay". ClayGeek. Retrieved 2024-10-01.

- ^ "The 6 different stages of clay". Oxford Clay Handmade Ceramics - Eco-conscious pottery. Retrieved 2024-10-01.

- ^ a b 'The Emergence Of Ceramic Technology And Its Evolution As Revealed With The Use Of Scientific Techniques.' Y. Maniatis. Mine to Microscope: Advances in the Study of Ancient. (ed. A.J. Shortland, I.C. Freestone and T. Rehren ) Oxbow Books, Oxford, (2009). Chapter 2.

- ^ a b 'The Firing Of Clay-Based Ceramics.' W. H. Holmes. Science Progress. Vol. 60, No. 237 (Spring 1972), pg. 98

- ^ Sutton, W.H. Microwave Processing of Ceramics – An Overview. MRS Online Proceedings Library 269, 3–20 (1992).

- ^ "History of Pottery". Brothers-handmade.com. Archived from the original on 2013-06-01. Retrieved 2010-09-04.

- ^ Malaxi Teams. "Labu Sayong, Perak". Malaxi.com. Archived from the original on 2012-11-04. Retrieved 2010-09-04.

- ^ Goldner, Janet (Spring 2007). "The women of Kalabougou". African Arts. 40 (1): 74–79. doi:10.1162/afar.2007.40.1.74. S2CID 57567441.

- ^ "The Fast Firing Of Biscuit Earthenware Hollow-Ware In a Single-Layer Tunnel Kiln." Salt D.L. Holmes W.H. RP737. Ceram Research.

- ^ "New And Latest Biscuit Firing Technology". Porzellanfabriken Christian Seltmann GmbH. Ceram.Forum Int./Ber.DKG 87, No. 1/2, pp. E33–E34, E36. 2010

- ^ "Clay Sewer Pipe Manufacture. Part II – The Effect Of Variable Alumina, Silica And Iron Oxide In Clays On Some Properties Of Salt Glazes." H.G. Schurecht. The Journal of the American Ceramic Society. Volume 6. Issue 6, pp. 717–29.

- ^ "Dictionary Of Ceramics." Arthur Dodd & David Murfin. 3rd edition. The Institute Of Minerals. 1994.

- ^ "Ash Glaze Research." C. Metcalfe. Ceramic Review No. 202. 2003. pp. 48–50.

- ^ "Glaze From Wood Ashes And Their Colour Characteristics." Y-S. Han, B-H. Lee. Korean Ceramic Society 41. No. 2. 2004.

- ^ "Stoke Museums – Health Risks in a Victorian Pottery Industry". 7 July 2012. Archived from the original on 7 July 2012. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- ^ "Timeline – History of Occupational Safety and Health".

- ^ 'The Successful Prevention Of Silicosis Among China Biscuit Workers In The North Staffordshire Potteries.' A. Meiklejohn. British Journal Of Industrial Medicine, October 1963; 20(4): 255–263

- ^ 'A Case Of Silicosis In The Ceramic Sector. Y. Yurt, M. Turk. EJMI. 2018; 2(1): 50–52

- ^ Silicosis, nhs.uk

- ^ Cancer warning: The type of dust linked to a higher risk of lung cancer – 'harmful', express.co.uk, 12 July 2022

- ^ "The Pottery (Health and Welfare) Special Regulations 1950".

- ^ 'Whitewares: Production, Testing And Quality Control." W.Ryan & C.Radford. Pergamon Press. 1987

- ^ "Is Pottery Clay Eco-Friendly? – or is it Costing the Earth?". Pottery Tips by the Pottery Wheel. 2020-07-14. Retrieved 2022-05-10.

- ^ William K. Barnett and John W. Hoopes, The Emergence of Pottery: Technology and Innovation in Ancient Society, Smithsonian Institution Press, 1995, p. 19

- ^ Metropolitan Museum of Art "Jomon Culture (Ca. 10,500-ca. 300 B.C.) | Thematic Essay | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History | the Metropolitan Museum of Art". Archived from the original on 2011-09-06. Retrieved 2011-09-15.

- ^ Haarmann, Harald (2020). Advancement in Ancient Civilizations: Life, Culture, Science and Thought. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers. p. 40. ISBN 978-1-4766-4075-4.

- ^ Glenn C. Nelson, Ceramics: A Potter's Handbook,1966, Holt, Rinehart and Winston, Inc., p. 251

- ^ Cooper (2010)

- ^ Nelson (1966), p. 251

- ^ a b Cooper (2010), p. 16

- ^ Bar-Yosef, Ofer; Arpin, Trina; Pan, Yan; Cohen, David; Goldberg, Paul; Zhang, Chi; Wu, Xiaohong (29 June 2012). "Early Pottery at 20,000 Years Ago in Xianrendong Cave, China". Science. 336 (6089): 1696–1700. Bibcode:2012Sci...336.1696W. doi:10.1126/science.1218643. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 22745428. S2CID 37666548.

- ^ Marshall, Michael (2012). "Oldest pottery hints at cooking's ice-age origins". New Scientist. 215 (2872): 14. Bibcode:2012NewSc.215Q..14M. doi:10.1016/S0262-4079(12)61728-X. Archived from the original on 2019-10-20. Retrieved 2019-05-10.

- ^ a b "Chinese pottery may be earliest discovered." Archived 2012-10-06 at the Wayback Machine Associated Press. 2009-06-01.

- ^ "Remnants of an Ancient Kitchen Are Found in China" Archived 2017-03-15 at the Wayback Machine. The New York Times.

- ^ Wu, X.; Zhang, C.; Goldberg, P.; Cohen, D.; Pan, Y.; Arpin, T.; Bar-Yosef, O. (June 29, 2012). "Early Pottery at 20,000 Years Ago in Xianren Cave, China". Science. 336 (6089): 1696–700. Bibcode:2012Sci...336.1696W. doi:10.1126/science.1218643. PMID 22745428. S2CID 37666548.

- ^ "Harvard, BU researchers find evidence of 20,000-year-old pottery" Archived 2017-07-28 at the Wayback Machine. The Boston Globe.

- ^ 'Radiocarbon Dating Of Charcoal And Bone Collagen Associated With Early Pottery At Yuchanyan Cave, Hunan Province, China.' Boaretto E., Wu X., Yuan J., Bar-Yosef O., Chu V., Pan Y., Liu K., Cohen D., Jiao T., Li S., Gu H., Goldberg P., Weiner S. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. June 2009. 16;106(24): 9595–600.

- ^ Kainer, Simon (September 2003). "The Oldest Pottery in the World" (PDF). Current World Archaeology. Robert Selkirk. pp. 44–49. Archived from the original on 2006-04-23. Retrieved 2016-09-27.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b O.E. Craig, H. Saul, A. Lucquin, Y. Nishida, K. Taché, L. Clarke, A. Thompson, D.T. Altoft, J. Uchiyama, M. Ajimoto, K. Gibbs, S. Isaksson, C.P. Heron P. Jordan (18 April 2013). "Earliest evidence for the use of pottery". Nature. 496 (7445): 351–54. arXiv:1510.02343. Bibcode:2013Natur.496..351C. doi:10.1038/nature12109. hdl:10454/5947. PMID 23575637. S2CID 3094491.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Barnett & Hoopes 1995:211

- ^ Cooper (2010), p. 75

- ^ Cooper (2010), p. 79

- ^ Cooper (2010), pp. 160–62

- ^ D. Petraglia, Michael (26 March 2007). The Evolution and History of Human Populations in South Asia (2007 ed.). Springer. p. 407. ISBN 9781402055614. Archived from the original on 1 January 2014. Retrieved 26 March 2007.

- ^ Bulletin of the Deccan College Research Institute, Volume 49, Dr. A. M. Ghatage, Page 303–304

- ^ Upinder Singh (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone age to the 12th century. Pearson Education India. p. 76. ISBN 9788131716779. Archived from the original on 2020-12-14. Retrieved 2020-06-04.

- ^ Peter Bellwood; Immanuel Ness (2014-11-10). The Global Prehistory of Human Migration. John Wiley & Sons. p. 250. ISBN 9781118970591. Archived from the original on 2020-07-28. Retrieved 2020-06-04.

- ^ Gwen Robbins Schug; Subhash R. Walimbe (2016-04-13). A Companion to South Asia in the Past. John Wiley & Sons. p. 350. ISBN 9781119055471. Archived from the original on 2021-07-01. Retrieved 2020-06-04.

- ^ Barker, Graeme; Goucher, Candice (2015). The Cambridge World History: Volume 2, A World with Agriculture, 12,000 BCE–500 CE. Cambridge University Press. p. 470. ISBN 9781316297780. Archived from the original on 2020-07-28. Retrieved 2019-10-21.

- ^ Cahill, Michael A. (2012). Paradise Rediscovered: The Roots of Civilisation. Interactive Publications. p. 104. ISBN 9781921869488.

- ^ Proceedings, American Philosophical Society (vol. 85, 1942). ISBN 1-4223-7221-9

- ^ Archaeology of the United Arab Emirates: Proceedings of the First International Conference on the Archaeology of the U.A.E. By Daniel T. Potts, Hasan Al Naboodah, Peter Hellyer. Contributor Daniel T. Potts, Hasan Al Naboodah, Peter Hellyer. Published 2003. Trident Press Ltd. ISBN 1-900724-88-X

- ^ The pottery trail from Southeast Asia to remote Oceania, MT Carson, H Hung, G Summerhayes, 2013

- ^ The incised & impressed pottery style of mainland Southeast Asia: following the paths of Neolithization F Rispoli – East and West, 2007

- ^ Sa-huỳnh Related Pottery in Southeast Asia WG Solheim – Asian Perspectives, 1959

- ^ The Kulanay pottery complex in the Philippines WG Solheim – Artibus Asiae, 1957

- ^ "Metropolitan Museum of Art". Metmuseum.org. Archived from the original on 2019-04-22. Retrieved 2019-04-26.

- ^ Cooper (2010), pp. 19–20

- ^ Cooper (2010), pp. 20–24

- ^ D. W. Anthony. The Horse, the Wheel, and Language. P. 149.

- ^ Cooper (2010), pp. 36–37

- ^ Cooper (2010), p. 42

- ^ "Deutsches Museum: History". Archived from the original on 2016-07-07. "Deutsches Museum: History". Archived from the original on 2019-12-28. Retrieved 2021-12-31.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Richard Whipp, Patterns of Labour – Work and Social Change in the Pottery Industry (1990).

- ^ Simeon Shaw, History of the Staffordshire Potteries: And the Rise and Progress of the Manufacture of Pottery and Porcelain; with References to Genuine Specimens, and Notices of Eminent Potters (1900) online.

- ^ Brian Dolan, Wedgwood: The First Tycoon (2004).

- ^ Aileen Dawson, ""The Growth of the Staffordshire Ceramic Industry", in Freestone, Ian, Gaimster, David R. M. (eds), Pottery in the Making: World Ceramic Traditions (1997), pp 200–205

- ^ Dawson, 200–201

- ^ Ridge, Mian (29 May 2002). "Gone to pot". The Guardian.

- ^ Nelson (1966), pp. 23–26

- ^ Watson, Derek J. (2 October 2017). "Bosumpra revisited: 12,500 years on the Kwahu Plateau, Ghana, as viewed from "On top of the hill"". Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa. 52 (4): 437–517. doi:10.1080/0067270X.2017.1393925. S2CID 165755536.

- ^ Cerasoni, Jacopo Niccolò; et al. (17 March 2023). "Human interactions with tropical environments over the last 14,000 years at Iho Eleru, Nigeria". iScience. 26 (3): 106153. Bibcode:2023iSci...26j6153C. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2023.106153. ISSN 2589-0042. OCLC 9806331324. PMC 9950523. PMID 36843842. S2CID 256747182.

- ^ "Aboriginal Culture: Introduction". Archived from the original on March 16, 2015.

- ^ "History of Australian Pottery". Archived from the original on March 17, 2012.

Further reading

[edit]- ASTM Standard C 242-01 Standard Terminology of Ceramic Whitewares and Related Products

- Ashmore, Wendy & Sharer, Robert J., (2000). Discovering Our Past: A Brief Introduction to Archaeology Third Edition. Mountain View, CA: Mayfield Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-07-297882-7

- Barnett, William & Hoopes, John (Eds.) (1995). The Emergence of Pottery. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press. ISBN 1-56098-517-8

- Childe, V.G., (1951). Man Makes Himself. London: Watts & Co.

- Freestone, Ian, Gaimster, David R.M., Pottery in the Making: World Ceramic Traditions, 1997, British Museum Publications, ISBN 0-7141-1782-X

- Rice, Prudence M. (1987). Pottery Analysis – A Sourcebook. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-71118-8.

- Savage, George, Pottery Through the Ages, Penguin, 1959, ISBN 9789120063317