Portal:Mathematics

- አማርኛ

- العربية

- Avañe'ẽ

- Авар

- تۆرکجه

- বাংলা

- 閩南語 / Bân-lâm-gú

- Беларуская (тарашкевіца)

- Bikol Central

- Български

- Català

- Cebuano

- Čeština

- الدارجة

- Deutsch

- Eesti

- Ελληνικά

- Español

- فارسی

- Français

- Gĩkũyũ

- 한국어

- Hausa

- Հայերեն

- हिन्दी

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Interlingua

- Íslenska

- Italiano

- עברית

- ქართული

- Қазақша

- Kiswahili

- Kreyòl ayisyen

- Kurdî

- Latina

- Lietuvių

- Magyar

- Македонски

- Malti

- مصرى

- ဘာသာမန်

- Bahasa Melayu

- မြန်မာဘာသာ

- Nederlands

- 日本語

- Oʻzbekcha / ўзбекча

- ਪੰਜਾਬੀ

- پښتو

- Picard

- Polski

- Português

- Română

- Runa Simi

- Русский

- Shqip

- සිංහල

- سنڌي

- Slovenčina

- Soomaaliga

- کوردی

- Српски / srpski

- Suomi

- Svenska

- தமிழ்

- Taclḥit

- Татарча / tatarça

- တႆး

- ไทย

- Тоҷикӣ

- Türkçe

- Українська

- اردو

- Tiếng Việt

- 文言

- 吴语

- ייִדיש

- Yorùbá

- 粵語

- Zazaki

- 中文

- Batak Mandailing

- ⵜⴰⵎⴰⵣⵉⵖⵜ ⵜⴰⵏⴰⵡⴰⵢⵜ

Appearance

Portal maintenance status: (December 2018)

|

Wikipedia portal for content related to Mathematics

-

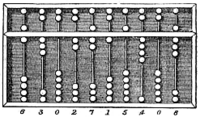

The Abacus, a ancient hand-operated mechanical wood-built calculator.

-

Portrait of Emmy Noether, around 1900.

Mathematics is a field of study that discovers and organizes methods, theories and theorems that are developed and proved for the needs of empirical sciences and mathematics itself. There are many areas of mathematics, which include number theory (the study of numbers), algebra (the study of formulas and related structures), geometry (the study of shapes and spaces that contain them), analysis (the study of continuous changes), and set theory (presently used as a foundation for all mathematics). (Full article...)

Featured articles

-

Image 1

Richard Phillips Feynman (/ˈfaɪnmən/; May 11, 1918 – February 15, 1988) was an American theoretical physicist. He is best known for his work in the path integral formulation of quantum mechanics, the theory of quantum electrodynamics, the physics of the superfluidity of supercooled liquid helium, and in particle physics, for which he proposed the parton model. For his contributions to the development of quantum electrodynamics, Feynman received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1965 jointly with Julian Schwinger and Shin'ichirō Tomonaga.

Feynman developed a widely used pictorial representation scheme for the mathematical expressions describing the behavior of subatomic particles, which later became known as Feynman diagrams. During his lifetime, Feynman became one of the best-known scientists in the world. In a 1999 poll of 130 leading physicists worldwide by the British journal Physics World, he was ranked the seventh-greatest physicist of all time. (Full article...) -

Image 2

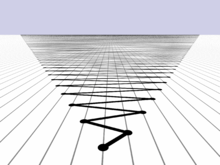

Logic studies valid forms of inference like modus ponens.

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the study of deductively valid inferences or logical truths. It examines how conclusions follow from premises based on the structure of arguments alone, independent of their topic and content. Informal logic is associated with informal fallacies, critical thinking, and argumentation theory. Informal logic examines arguments expressed in natural language whereas formal logic uses formal language. When used as a countable noun, the term "a logic" refers to a specific logical formal system that articulates a proof system. Logic plays a central role in many fields, such as philosophy, mathematics, computer science, and linguistics.

Logic studies arguments, which consist of a set of premises that leads to a conclusion. An example is the argument from the premises "it's Sunday" and "if it's Sunday then I don't have to work" leading to the conclusion "I don't have to work". Premises and conclusions express propositions or claims that can be true or false. An important feature of propositions is their internal structure. For example, complex propositions are made up of simpler propositions linked by logical vocabulary like(and) or

(if...then). Simple propositions also have parts, like "Sunday" or "work" in the example. The truth of a proposition usually depends on the meanings of all of its parts. However, this is not the case for logically true propositions. They are true only because of their logical structure independent of the specific meanings of the individual parts. (Full article...)

-

Image 3

The first 15,000 partial sums of 0 + 1 − 2 + 3 − 4 + ... The graph is situated with positive integers to the right and negative integers to the left.

In mathematics, 1 − 2 + 3 − 4 + ··· is an infinite series whose terms are the successive positive integers, given alternating signs. Using sigma summation notation the sum of the first m terms of the series can be expressed as

The infinite series diverges, meaning that its sequence of partial sums, (1, −1, 2, −2, 3, ...), does not tend towards any finite limit. Nonetheless, in the mid-18th century, Leonhard Euler wrote what he admitted to be a paradoxical equation:(Full article...)

-

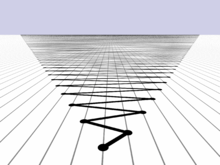

Image 4General relativity, also known as the general theory of relativity, and as Einstein's theory of gravity, is the geometric theory of gravitation published by Albert Einstein in 1915 and is the current description of gravitation in modern physics. General relativity generalizes special relativity and refines Newton's law of universal gravitation, providing a unified description of gravity as a geometric property of space and time, or four-dimensional spacetime. In particular, the curvature of spacetime is directly related to the energy and momentum of whatever is

present, including matter and radiation. The relation is specified by the Einstein field equations, a system of second-order partial differential equations.

Newton's law of universal gravitation, which describes classical gravity, can be seen as a prediction of general relativity for the almost flat spacetime geometry around stationary mass distributions. Some predictions of general relativity, however, are beyond Newton's law of universal gravitation in classical physics. These predictions concern the passage of time, the geometry of space, the motion of bodies in free fall, and the propagation of light, and include gravitational time dilation, gravitational lensing, the gravitational redshift of light, the Shapiro time delay and singularities/black holes. So far, all tests of general relativity have been shown to be in agreement with the theory. The time-dependent solutions of general relativity enable us to talk about the history of the universe and have provided the modern framework for cosmology, thus leading to the discovery of the Big Bang and cosmic microwave background radiation. Despite the introduction of a number of alternative theories, general relativity continues to be the simplest theory consistent with experimental data. (Full article...) -

Image 5

The manipulations of the Rubik's Cube form the Rubik's Cube group.

In mathematics, a group is a set with an operation that satisfies the following constraints: the operation is associative, it has an identity element, and every element of the set has an inverse element.

Many mathematical structures are groups endowed with other properties. For example, the integers with the addition operation form an infinite group, which is generated by a single element called (these properties characterize the integers in a unique way). (Full article...)

-

Image 6

The weighing pans of this balance scale contain zero objects, divided into two equal groups.

In mathematics, zero is an even number. In other words, its parity—the quality of an integer being even or odd—is even. This can be easily verified based on the definition of "even": zero is an integer multiple of 2, specifically 0 × 2. As a result, zero shares all the properties that characterize even numbers: for example, 0 is neighbored on both sides by odd numbers, any decimal integer has the same parity as its last digit—so, since 10 is even, 0 will be even, and if y is even then y + x has the same parity as x—indeed, 0 + x and x always have the same parity.

Zero also fits into the patterns formed by other even numbers. The parity rules of arithmetic, such as even − even = even, require 0 to be even. Zero is the additive identity element of the group of even integers, and it is the starting case from which other even natural numbers are recursively defined. Applications of this recursion from graph theory to computational geometry rely on zero being even. Not only is 0 divisible by 2, it is divisible by every power of 2, which is relevant to the binary numeral system used by computers. In this sense, 0 is the "most even" number of all. (Full article...) -

Image 7One of Molyneux's celestial globes, which is displayed in Middle Temple Library – from the frontispiece of the Hakluyt Society's 1889 reprint of A Learned Treatise of Globes, both Cœlestiall and Terrestriall, one of the English editions of Robert Hues' Latin work Tractatus de Globis (1594)

Emery Molyneux (/ˈɛməri ˈmɒlɪnoʊ/ EM-ər-ee MOL-in-oh; died June 1598) was an English Elizabethan maker of globes, mathematical instruments and ordnance. His terrestrial and celestial globes, first published in 1592, were the first to be made in England and the first to be made by an Englishman.

Molyneux was known as a mathematician and maker of mathematical instruments such as compasses and hourglasses. He became acquainted with many prominent men of the day, including the writer Richard Hakluyt and the mathematicians Robert Hues and Edward Wright. He also knew the explorers Thomas Cavendish, Francis Drake, Walter Raleigh and John Davis. Davis probably introduced Molyneux to his own patron, the London merchant William Sanderson, who largely financed the construction of the globes. When completed, the globes were presented to Elizabeth I. Larger globes were acquired by royalty, noblemen and academic institutions, while smaller ones were purchased as practical navigation aids for sailors and students. The globes were the first to be made in such a way that they were unaffected by the humidity at sea, and they came into general use on ships. (Full article...) -

Image 8Portrait by August Köhler, c. 1910, after 1627 original

Johannes Kepler (/ˈkɛplər/; German: [joˈhanəs ˈkɛplɐ, -nɛs -] ⓘ; 27 December 1571 – 15 November 1630) was a German astronomer, mathematician, astrologer, natural philosopher and writer on music. He is a key figure in the 17th-century Scientific Revolution, best known for his laws of planetary motion, and his books Astronomia nova, Harmonice Mundi, and Epitome Astronomiae Copernicanae, influencing among others Isaac Newton, providing one of the foundations for his theory of universal gravitation. The variety and impact of his work made Kepler one of the founders and fathers of modern astronomy, the scientific method, natural and modern science. He has been described as the "father of science fiction" for his novel Somnium.

Kepler was a mathematics teacher at a seminary school in Graz, where he became an associate of Prince Hans Ulrich von Eggenberg. Later he became an assistant to the astronomer Tycho Brahe in Prague, and eventually the imperial mathematician to Emperor Rudolf II and his two successors Matthias and Ferdinand II. He also taught mathematics in Linz, and was an adviser to General Wallenstein.

Additionally, he did fundamental work in the field of optics, being named the father of modern optics, in particular for his Astronomiae pars optica. He also invented an improved version of the refracting telescope, the Keplerian telescope, which became the foundation of the modern refracting telescope, while also improving on the telescope design by Galileo Galilei, who mentioned Kepler's discoveries in his work. He is also known for postulating the Kepler conjecture. (Full article...) -

Image 9In algebraic geometry and theoretical physics, mirror symmetry is a relationship between geometric objects called Calabi–Yau manifolds. The term refers to a situation where two Calabi–Yau manifolds look very different geometrically but are nevertheless equivalent when employed as extra dimensions of string theory.

Early cases of mirror symmetry were discovered by physicists. Mathematicians became interested in this relationship around 1990 when Philip Candelas, Xenia de la Ossa, Paul Green, and Linda Parkes showed that it could be used as a tool in enumerative geometry, a branch of mathematics concerned with counting the number of solutions to geometric questions. Candelas and his collaborators showed that mirror symmetry could be used to count rational curves on a Calabi–Yau manifold, thus solving a longstanding problem. Although the original approach to mirror symmetry was based on physical ideas that were not understood in a mathematically precise way, some of its mathematical predictions have since been proven rigorously. (Full article...) -

Image 10

Plots of logarithm functions, with three commonly used bases. The special points logb b = 1 are indicated by dotted lines, and all curves intersect in logb 1 = 0.

In mathematics, the logarithm of a number is the exponent by which another fixed value, the base, must be raised to produce that number. For example, the logarithm of 1000 to base 10 is 3, because 1000 is 10 to the 3rd power: 1000 = 103 = 10 × 10 × 10. More generally, if x = by, then y is the logarithm of x to base b, written logb x, so log10 1000 = 3. As a single-variable function, the logarithm to base b is the inverse of exponentiation with base b.

The logarithm base 10 is called the decimal or common logarithm and is commonly used in science and engineering. The natural logarithm has the number e ≈ 2.718 as its base; its use is widespread in mathematics and physics because of its very simple derivative. The binary logarithm uses base 2 and is widely used in computer science, information theory, music theory, and photography. When the base is unambiguous from the context or irrelevant it is often omitted, and the logarithm is written log x. (Full article...) -

Image 11

Josiah Willard Gibbs (/ɡɪbz/; February 11, 1839 – April 28, 1903) was an American scientist who made significant theoretical contributions to physics, chemistry, and mathematics. His work on the applications of thermodynamics was instrumental in transforming physical chemistry into a rigorous deductive science. Together with James Clerk Maxwell and Ludwig Boltzmann, he created statistical mechanics (a term that he coined), explaining the laws of thermodynamics as consequences of the statistical properties of ensembles of the possible states of a physical system composed of many particles. Gibbs also worked on the application of Maxwell's equations to problems in physical optics. As a mathematician, he created modern vector calculus (independently of the British scientist Oliver Heaviside, who carried out similar work during the same period) and described the Gibbs phenomenon in the theory of Fourier analysis.

In 1863, Yale University awarded Gibbs the first American doctorate in engineering. After a three-year sojourn in Europe, Gibbs spent the rest of his career at Yale, where he was a professor of mathematical physics from 1871 until his death in 1903. Working in relative isolation, he became the earliest theoretical scientist in the United States to earn an international reputation and was praised by Albert Einstein as "the greatest mind in American history". In 1901, Gibbs received what was then considered the highest honor awarded by the international scientific community, the Copley Medal of the Royal Society of London, "for his contributions to mathematical physics". (Full article...) -

Image 12The number π (/paɪ/ ⓘ; spelled out as "pi") is a mathematical constant, approximately equal to 3.14159, that is the ratio of a circle's circumference to its diameter. It appears in many formulae across mathematics and physics, and some of these formulae are commonly used for defining π, to avoid relying on the definition of the length of a curve.

The number π is an irrational number, meaning that it cannot be expressed exactly as a ratio of two integers, although fractions such asare commonly used to approximate it. Consequently, its decimal representation never ends, nor enters a permanently repeating pattern. It is a transcendental number, meaning that it cannot be a solution of an algebraic equation involving only finite sums, products, powers, and integers. The transcendence of π implies that it is impossible to solve the ancient challenge of squaring the circle with a compass and straightedge. The decimal digits of π appear to be randomly distributed, but no proof of this conjecture has been found. (Full article...)

-

Image 13

Amalie Emmy Noether (US: /ˈnʌtər/, UK: /ˈnɜːtə/; German: [ˈnøːtɐ]; 23 March 1882 – 14 April 1935) was a German mathematician who made many important contributions to abstract algebra. She also proved Noether's first and second theorems, which are fundamental in mathematical physics. Noether was described by Pavel Alexandrov, Albert Einstein, Jean Dieudonné, Hermann Weyl and Norbert Wiener as the most important woman in the history of mathematics. As one of the leading mathematicians of her time, she developed theories of rings, fields, and algebras. In physics, Noether's theorem explains the connection between symmetry and conservation laws.

Noether was born to a Jewish family in the Franconian town of Erlangen; her father was the mathematician Max Noether. She originally planned to teach French and English after passing the required examinations but instead studied mathematics at the University of Erlangen, where her father lectured. After completing her doctorate in 1907 under the supervision of Paul Gordan, she worked at the Mathematical Institute of Erlangen without pay for seven years. At the time, women were largely excluded from academic positions. In 1915, she was invited by David Hilbert and Felix Klein to join the mathematics department at the University of Göttingen, a world-renowned center of mathematical research. The philosophical faculty objected, however, and she spent four years lecturing under Hilbert's name. Her habilitation was approved in 1919, allowing her to obtain the rank of Privatdozent. (Full article...) -

Image 14

The Quine–Putnam indispensability argument is an argument in the philosophy of mathematics for the existence of abstract mathematical objects such as numbers and sets, a position known as mathematical platonism. It was named after the philosophers Willard Van Orman Quine and Hilary Putnam, and is one of the most important arguments in the philosophy of mathematics.

Although elements of the indispensability argument may have originated with thinkers such as Gottlob Frege and Kurt Gödel, Quine's development of the argument was unique for introducing to it a number of his philosophical positions such as naturalism, confirmational holism, and the criterion of ontological commitment. Putnam gave Quine's argument its first detailed formulation in his 1971 book Philosophy of Logic. He later came to disagree with various aspects of Quine's thinking, however, and formulated his own indispensability argument based on the no miracles argument in the philosophy of science. A standard form of the argument in contemporary philosophy is credited to Mark Colyvan; whilst being influenced by both Quine and Putnam, it differs in important ways from their formulations. It is presented in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: (Full article...) -

Image 15Portrait by Jakob Emanuel Handmann, 1753

Leonhard Euler (/ˈɔɪlər/ OY-lər; German: [ˈleːɔnhaʁt ˈʔɔʏlɐ] ⓘ, Swiss Standard German: [ˈleɔnhard ˈɔʏlər]; 15 April 1707 – 18 September 1783) was a Swiss polymath who was active as a mathematician, physicist, astronomer, logician, geographer, and engineer. He founded the studies of graph theory and topology and made influential discoveries in many other branches of mathematics, such as analytic number theory, complex analysis, and infinitesimal calculus. He also introduced much of modern mathematical terminology and notation, including the notion of a mathematical function. He is known for his work in mechanics, fluid dynamics, optics, astronomy, and music theory. Euler has been called a "universal genius" who "was fully equipped with almost unlimited powers of imagination, intellectual gifts and extraordinary memory". He spent most of his adult life in Saint Petersburg, Russia, and in Berlin, then the capital of Prussia.

Euler is credited for popularizing the Greek letter(lowercase pi) to denote the ratio of a circle's circumference to its diameter, as well as first using the notation

for the value of a function, the letter

to express the imaginary unit

, the Greek letter

(capital sigma) to express summations, the Greek letter

(capital delta) for finite differences, and lowercase letters to represent the sides of a triangle while representing the angles as capital letters. He gave the current definition of the constant

, the base of the natural logarithm, now known as Euler's number. Euler made contributions to applied mathematics and engineering, such as his study of ships which helped navigation, his three volumes on optics contributed to the design of microscopes and telescopes, and he studied the bending of beams and the critical load of columns. (Full article...)

Good articles

-

Image 1In mathematics, a square-difference-free set is a set of natural numbers, no two of which differ by a square number. Hillel Furstenberg and András Sárközy proved in the late 1970s the Furstenberg–Sárközy theorem of additive number theory showing that, in a certain sense, these sets cannot be very large. In the game of subtract a square, the positions where the next player loses form a square-difference-free set. Another square-difference-free set is obtained by doubling the Moser–de Bruijn sequence.

The best known upper bound on the size of a square-difference-free set of numbers up tois only slightly sublinear, but the largest known sets of this form are significantly smaller, of size

. Closing the gap between these upper and lower bounds remains an open problem. The sublinear size bounds on square-difference-free sets can be generalized to sets where certain other polynomials are forbidden as differences between pairs of elements. (Full article...)

-

Image 2

Selected witch of Agnesi curves (green), and the circles they are constructed from (blue), with radius parameters ,

,

, and

.

In mathematics, the witch of Agnesi (Italian pronunciation: [aɲˈɲeːzi, -eːsi; -ɛːzi]) is a cubic plane curve defined from two diametrically opposite points of a circle.

The curve was studied as early as 1653 by Pierre de Fermat, in 1703 by Guido Grandi, and by Isaac Newton. It gets its name from Italian mathematician Maria Gaetana Agnesi who published it in 1748. The Italian name la versiera di Agnesi is based on Latin versoria (sheet of sailing ships) and the sinus versus.

This was read by John Colson as l’avversiera di Agnesi, where avversiera is translated as "woman who is against God" and interpreted as "witch". (Full article...) -

Image 3

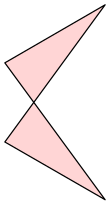

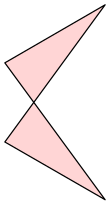

An antiparallelogram

In geometry, an antiparallelogram is a type of self-crossing quadrilateral. Like a parallelogram, an antiparallelogram has two opposite pairs of equal-length sides, but these pairs of sides are not in general parallel. Instead, each pair of sides is antiparallel with respect to the other, with sides in the longer pair crossing each other as in a scissors mechanism. Whereas a parallelogram's opposite angles are equal and oriented the same way, an antiparallelogram's are equal but oppositely oriented. Antiparallelograms are also called contraparallelograms or crossed parallelograms.

Antiparallelograms occur as the vertex figures of certain nonconvex uniform polyhedra. In the theory of four-bar linkages, the linkages with the form of an antiparallelogram are also called butterfly linkages or bow-tie linkages, and are used in the design of non-circular gears. In celestial mechanics, they occur in certain families of solutions to the 4-body problem. (Full article...) -

Image 4

A simplicial line arrangement (left) and a simple line arrangement (right).

In geometry, an arrangement of lines is the subdivision of the Euclidean plane formed by a finite set of lines. An arrangement consists of bounded and unbounded convex polygons, the cells of the arrangement, line segments and rays, the edges of the arrangement, and points where two or more lines cross, the vertices of the arrangement. When considered in the projective plane rather than in the Euclidean plane, every two lines cross, and an arrangement is the projective dual to a finite set of points. Arrangements of lines have also been considered in the hyperbolic plane, and generalized to pseudolines, curves that have similar topological properties to lines. The initial study of arrangements has been attributed to an 1826 paper by Jakob Steiner.

An arrangement is said to be simple when at most two lines cross at each vertex, and simplicial when all cells are triangles (including the unbounded cells, as subsets of the projective plane). There are three known infinite families of simplicial arrangements, as well as many sporadic simplicial arrangements that do not fit into any known family. Arrangements have also been considered for infinite but locally finite systems of lines. Certain infinite arrangements of parallel lines can form simplicial arrangements, and one way of constructing the aperiodic Penrose tiling involves finding the dual graph of an arrangement of lines forming five parallel subsets. (Full article...) -

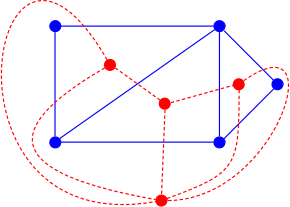

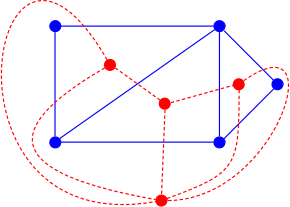

Image 5The Earth–Moon problem is an unsolved problem on graph coloring in mathematics. It is an extension of the planar map coloring problem (solved by the four color theorem), and was posed by Gerhard Ringel in 1959. An intuitive form of the problem asks how many colors are needed to color political maps of the Earth and Moon, in a hypothetical future where each Earth country has a Moon colony which must be given the same color. In mathematical terms, it seeks the chromatic number of biplanar graphs. It is known that this number is at least 9 and at most 12.

The Earth–Moon problem has been extended to analogous problems of coloring maps on any number of planets. For this extension the lower bounds and upper bounds on the number of colors are closer, within two of each other. One real-world application of the Earth–Moon problem involves testing printed circuit boards. (Full article...) -

Image 6

A binary tiling in the Poincaré disk model of the hyperbolic plane. Each tile edge lies on a horocycle (shown as circles interior to the disk) or a hyperbolic line (arcs perpendicular to the disk boundary). The horocycles and lines are asymptotic to an ideal point located at the right side of the Poincaré disk.

In geometry, a binary tiling (sometimes called a Böröczky tiling) is a tiling of the hyperbolic plane, resembling a quadtree over the Poincaré half-plane model of the hyperbolic plane. The tiles are congruent, each adjoining five others. They may be convex pentagons, or non-convex shapes with four sides, alternatingly line segments and horocyclic arcs, meeting at four right angles.

There are uncountably many distinct binary tilings for a given shape of tile. They are all weakly aperiodic, which means that they can have a one-dimensional symmetry group but not a two-dimensional family of symmetries. There exist binary tilings with tiles of arbitrarily small area. (Full article...) -

Image 7

The red graph is the dual graph of the blue graph, and vice versa.

In the mathematical discipline of graph theory, the dual graph of a planar graph G is a graph that has a vertex for each face of G. The dual graph has an edge for each pair of faces in G that are separated from each other by an edge, and a self-loop when the same face appears on both sides of an edge. Thus, each edge e of G has a corresponding dual edge, whose endpoints are the dual vertices corresponding to the faces on either side of e. The definition of the dual depends on the choice of embedding of the graph G, so it is a property of plane graphs (graphs that are already embedded in the plane) rather than planar graphs (graphs that may be embedded but for which the embedding is not yet known). For planar graphs generally, there may be multiple dual graphs, depending on the choice of planar embedding of the graph.

Historically, the first form of graph duality to be recognized was the association of the Platonic solids into pairs of dual polyhedra. Graph duality is a topological generalization of the geometric concepts of dual polyhedra and dual tessellations, and is in turn generalized combinatorially by the concept of a dual matroid. Variations of planar graph duality include a version of duality for directed graphs, and duality for graphs embedded onto non-planar two-dimensional surfaces. (Full article...) -

Image 8In mathematics, the factorial of a non-negative integer

, denoted by

, is the product of all positive integers less than or equal to

. The factorial of

also equals the product of

with the next smaller factorial:

For example,

The value of 0! is 1, according to the convention for an empty product.

Factorials have been discovered in several ancient cultures, notably in Indian mathematics in the canonical works of Jain literature, and by Jewish mystics in the Talmudic book Sefer Yetzirah. The factorial operation is encountered in many areas of mathematics, notably in combinatorics, where its most basic use counts the possible distinct sequences – the permutations – ofdistinct objects: there are

. In mathematical analysis, factorials are used in power series for the exponential function and other functions, and they also have applications in algebra, number theory, probability theory, and computer science. (Full article...)

-

Image 9Advanced Placement (AP) Statistics (also known as AP Stats) is a college-level high school statistics course offered in the United States through the College Board's Advanced Placement program. This course is equivalent to a one semester, non-calculus-based introductory college statistics course and is normally offered to sophomores, juniors and seniors in high school.

One of the College Board's more recent additions, the AP Statistics exam was first administered in May 1996 to supplement the AP program's math offerings, which had previously consisted of only AP Calculus AB and BC. In the United States, enrollment in AP Statistics classes has increased at a higher rate than in any other AP class. (Full article...) -

Image 10

Composite numbers can be arranged into rectangles but prime numbers cannot.

A prime number (or a prime) is a natural number greater than 1 that is not a product of two smaller natural numbers. A natural number greater than 1 that is not prime is called a composite number. For example, 5 is prime because the only ways of writing it as a product, 1 × 5 or 5 × 1, involve 5 itself. However, 4 is composite because it is a product (2 × 2) in which both numbers are smaller than 4. Primes are central in number theory because of the fundamental theorem of arithmetic: every natural number greater than 1 is either a prime itself or can be factorized as a product of primes that is unique up to their order.

The property of being prime is called primality. A simple but slow method of checking the primality of a given number , called trial division, tests whether

is a multiple of any integer between 2 and

. Faster algorithms include the Miller–Rabin primality test, which is fast but has a small chance of error, and the AKS primality test, which always produces the correct answer in polynomial time but is too slow to be practical. Particularly fast methods are available for numbers of special forms, such as Mersenne numbers. As of October 2024[update] the largest known prime number is a Mersenne prime with 41,024,320 decimal digits. (Full article...)

-

Image 11

A three-page book embedding of the complete graph K5. Because it is not a planar graph, it is not possible to embed this graph without crossings on fewer pages, so its book thickness is three.

In graph theory, a book embedding is a generalization of planar embedding of a graph to embeddings in a book, a collection of half-planes all having the same line as their boundary. Usually, the vertices of the graph are required to lie on this boundary line, called the spine, and the edges are required to stay within a single half-plane. The book thickness of a graph is the smallest possible number of half-planes for any book embedding of the graph. Book thickness is also called pagenumber, stacknumber or fixed outerthickness. Book embeddings have also been used to define several other graph invariants including the pagewidth and book crossing number.

Every graph with n vertices has book thickness at most, and this formula gives the exact book thickness for complete graphs. The graphs with book thickness one are the outerplanar graphs. The graphs with book thickness at most two are the subhamiltonian graphs, which are always planar; more generally, every planar graph has book thickness at most four. It is NP-hard to determine the exact book thickness of a given graph, with or without knowing a fixed vertex ordering along the spine of the book. Testing the existence of a three-page book embedding of a graph, given a fixed ordering of the vertices along the spine of the embedding, has unknown computational complexity: it is neither known to be solvable in polynomial time nor known to be NP-hard. (Full article...)

-

Image 12

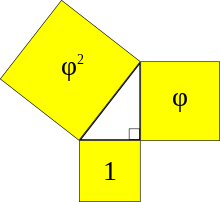

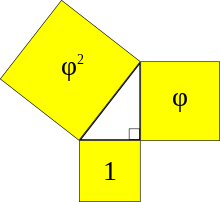

A Kepler triangle is a right triangle formed by three squares with areas in geometric progression according to the golden ratio.

A Kepler triangle is a special right triangle with edge lengths in geometric progression. The ratio of the progression iswhere

is the golden ratio, and the progression can be written:

, or approximately

. Squares on the edges of this triangle have areas in another geometric progression,

. Alternative definitions of the same triangle characterize it in terms of the three Pythagorean means of two numbers, or via the inradius of isosceles triangles.

This triangle is named after Johannes Kepler, but can be found in earlier sources. Although some sources claim that ancient Egyptian pyramids had proportions based on a Kepler triangle, most scholars believe that the golden ratio was not known to Egyptian mathematics and architecture. (Full article...)

Did you know

- ... that the British National Hospital Service Reserve trained volunteers to carry out first aid in the aftermath of a nuclear or chemical attack?

- ... that after Archimedes first defined convex curves, mathematicians lost interest in their analysis until the 19th century, more than two millennia later?

- ... that despite published scholarship to the contrary, Andrew Planta neither received a doctorate nor taught mathematics at Erlangen?

- ... that multiple mathematics competitions have made use of Sophie Germain's identity?

- ... that in 1967 two mathematicians published PhD dissertations independently disproving the same thirteen-year-old conjecture?

- ... that people in Madagascar perform algebra on tree seeds in order to tell the future?

- ... that Ewa Ligocka cooked another mathematician's goose?

- ... that in the aftermath of the American Civil War, the only Black-led organization providing teachers to formerly enslaved people was the African Civilization Society?

- ... that, according to the pizza theorem, a circular pizza that is sliced off-center into eight equal-angled wedges can still be divided equally between two people?

- ... that the clique problem of programming a computer to find complete subgraphs in an undirected graph was first studied as a way to find groups of people who all know each other in social networks?

- ... that the Herschel graph is the smallest possible polyhedral graph that does not have a Hamiltonian cycle?

- ... that the Life without Death cellular automaton, a mathematical model of pattern formation, is a variant of Conway's Game of Life in which cells, once brought to life, never die?

- ... that one can list every positive rational number without repetition by breadth-first traversal of the Calkin–Wilf tree?

- ... that the Hadwiger conjecture implies that the external surface of any three-dimensional convex body can be illuminated by only eight light sources, but the best proven bound is that 16 lights are sufficient?

- ... that an equitable coloring of a graph, in which the numbers of vertices of each color are as nearly equal as possible, may require far more colors than a graph coloring without this constraint?

Showing 7 items out of 75

Featured pictures

-

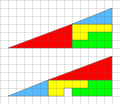

Image 2Proof of the Pythagorean theorem, by Joaquim Alves Gaspar (from Wikipedia:Featured pictures/Sciences/Mathematics)

-

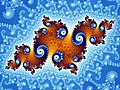

Image 3Mandelbrot set, step 11, by Wolfgangbeyer (from Wikipedia:Featured pictures/Sciences/Mathematics)

-

Image 4Mandelbrot set, step 8, by Wolfgangbeyer (from Wikipedia:Featured pictures/Sciences/Mathematics)

-

Image 5Fields Medal, back, by Stefan Zachow (edited by King of Hearts) (from Wikipedia:Featured pictures/Sciences/Mathematics)

-

Image 6Mandelbrot set, step 9, by Wolfgangbeyer (from Wikipedia:Featured pictures/Sciences/Mathematics)

-

Image 7Mandelbrot set, step 4, by Wolfgangbeyer (from Wikipedia:Featured pictures/Sciences/Mathematics)

-

Image 8Mandelbrot set, step 10, by Wolfgangbeyer (from Wikipedia:Featured pictures/Sciences/Mathematics)

-

Image 9Mandelbrot set, step 2, by Wolfgangbeyer (from Wikipedia:Featured pictures/Sciences/Mathematics)

-

Image 10Hypotrochoid, by Sam Derbyshire (edited by Anevrisme and Perhelion) (from Wikipedia:Featured pictures/Sciences/Mathematics)

-

Image 11Mandelbrot set, step 1, by Wolfgangbeyer (from Wikipedia:Featured pictures/Sciences/Mathematics)

-

Image 12Mandelbrot set, step 3, by Wolfgangbeyer (from Wikipedia:Featured pictures/Sciences/Mathematics)

-

Image 13Tetrahedral group at Symmetry group, by Debivort (from Wikipedia:Featured pictures/Sciences/Mathematics)

-

Image 15Mandelbrot set, by Simpsons contributor (from Wikipedia:Featured pictures/Sciences/Mathematics)

-

Image 16Mandelbrot set, step 7, by Wolfgangbeyer (from Wikipedia:Featured pictures/Sciences/Mathematics)

-

Image 17Mandelbrot set, step 14, by Wolfgangbeyer (from Wikipedia:Featured pictures/Sciences/Mathematics)

-

Image 19Mandelbrot set, step 13, by Wolfgangbeyer (from Wikipedia:Featured pictures/Sciences/Mathematics)

-

Image 20Non-uniform rational B-spline, by Greg L (from Wikipedia:Featured pictures/Sciences/Mathematics)

-

Image 21Fields Medal, front, by Stefan Zachow (edited by King of Hearts) (from Wikipedia:Featured pictures/Sciences/Mathematics)

-

Image 22Line integral of scalar field, by Lucas V. Barbosa (from Wikipedia:Featured pictures/Sciences/Mathematics)

-

Image 23Mandelbrot set, start, by Wolfgangbeyer (from Wikipedia:Featured pictures/Sciences/Mathematics)

-

Image 24Mandelbrot set, step 12, by Wolfgangbeyer (from Wikipedia:Featured pictures/Sciences/Mathematics)

-

Image 25Mandelbrot set, step 5, by Wolfgangbeyer (from Wikipedia:Featured pictures/Sciences/Mathematics)

-

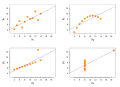

Image 26Anscombe's quartet, by Schutz (edited by Avenue) (from Wikipedia:Featured pictures/Sciences/Mathematics)

-

Image 27Desargues' theorem, by Dynablast (edited by Jujutacular and Julia W) (from Wikipedia:Featured pictures/Sciences/Mathematics)

-

Image 28Lorenz attractor at Chaos theory, by Wikimol (from Wikipedia:Featured pictures/Sciences/Mathematics)

-

Image 29Cellular automata at Reflector (cellular automaton), by Simpsons contributor (from Wikipedia:Featured pictures/Sciences/Mathematics)

-

Image 34Mandelbrot set, step 6, by Wolfgangbeyer (from Wikipedia:Featured pictures/Sciences/Mathematics)

Get involved

- For editor resources and to collaborate with other editors on improving Wikipedia's Mathematics-related articles, visit WikiProject Mathematics.

Categories

Topics

Index of articles

| ARTICLE INDEX: | |

| MATHEMATICIANS: |

Vital articles

- » subpages: Level 4 Mathematics articles, Level 5 Mathematics articles

Discover Wikipedia using portals

Hidden categories:

- Pages using the Phonos extension

- Pages with German IPA

- Pages including recorded pronunciations

- Pages with Swiss Standard German IPA

- Pages with Italian IPA

- Wikipedia semi-protected portals

- Manually maintained portal pages from December 2018

- All manually maintained portal pages

- Portals with triaged subpages from December 2018

- All portals with triaged subpages

- Portals with named maintainer

- Wikipedia move-protected portals

- Automated article-slideshow portals with 31–40 articles in article list

- Automated article-slideshow portals with 101–200 articles in article list

- Random portal component with over 50 available subpages