List of common misconceptions

This is a combined version of this list that displays on one page. In order to manage page size and loading time, the citations are excluded. If you want to view the citations, please click the links under each heading. |

Each entry on this list of common misconceptions is worded as a correction; the misconceptions themselves are implied rather than stated. These entries are concise summaries; the main subject articles can be consulted for more detail.

Common misconceptions are viewpoints or factoids that are often accepted as true, but which are actually false. They generally arise from conventional wisdom (such as old wives' tales), stereotypes, superstitions, fallacies, a misunderstanding of science, or the popularization of pseudoscience. Some common misconceptions are also considered to be urban legends, and they are sometimes involved in moral panics.

Arts and culture

[edit]View full version with citations

Business

[edit]- Federal legal tender laws in the United States do not require that private businesses, persons, or organizations accept cash for payment, though it must be treated as valid payment for debts when tendered to a creditor.

- Adidas is not an acronym for "All day I dream about sports", "All day I dream about soccer", or "All day I dream about sex". The company was named after its founder Adolf "Adi" Dassler in 1949. The earliest publication found of the latter backronym was in 1978, as a joke.

- The letters "AR" in AR-15 stand for "ArmaLite Rifle", reflecting the company (ArmaLite) that originally manufactured the weapon. They do not stand for "assault rifle".

- The Coca-Cola bottle's contour bottle was not designed by famous industrial designer Raymond Loewy.

- The common image of Santa Claus (Father Christmas) as a jolly large man in red garments was not created by the Coca-Cola Company as an advertising tool. Santa Claus had already taken this form in American popular culture by the late 19th century, long before Coca-Cola used his image in the 1930s.

- The Chevrolet Nova sold well in Latin American markets; General Motors did not rename the car. While no va does mean "doesn't go" in Spanish, nova was easily understood to mean "new".

- Netflix was not founded after its co-founder Reed Hastings was charged a $40 late fee by Blockbuster. Hastings made the story up to summarize Netflix's value proposition; Netflix's founders were actually inspired by Amazon.

- PepsiCo in no real sense ever owned the "6th most powerful navy" in the world after a deal with the Soviet Union. In 1989, Pepsi acquired several decommissioned warships as part of a barter deal. The oil tankers were leased out or sold and the other ships sold for scrap. A follow-on deal involved another 10 ships.

Fine arts

[edit]

- Ancient Greek and Roman sculptures were originally painted in colors; they appear white today only because the original pigments have deteriorated. Some well-preserved statues still bear traces of their original coloration.

- Michelangelo was standing instead of lying down while painting the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

Food and cooking

[edit]

- Searing does not seal in moisture in meat; it causes it to lose some moisture. Meat is seared to brown it and to affect its color, flavor, and texture.

- Braising meat does not add moisture; it causes it to lose some moisture. Moisture appears to be added when the gentle cooking breaks down connective tissue and collagen, which lubricates and tenderizes fibers.

- Mussels and clams that do not open when cooked can still be fully cooked and safe to eat.[better source needed]

- Twinkies, an American snack cake generally considered to be "junk food", have a shelf life of around 25 days, despite the common claim (usually facetious) that they remain edible for decades. The official shelf life is 45 days. Twinkies normally remain on a store shelf for 7 to 10 days.

- Packaged foods, when properly stored, can safely be eaten past their "expiration" dates in the US. While some US states regulate expiration dates for some products, generally "use-by" and "best-by" dates are manufacturer suggestions for best quality.

- Storing bread in the refrigerator makes it go stale faster than leaving it at room temperature. It does, however, slow mold growth.

- Crystallized honey is not spoiled. The crystals are formed by low temperature crystallization, a high glucose level, and the presence of pollen. The crystallization can be reversed by gentle heating.

- Seeds are not the spiciest part of chili peppers. In fact, seeds contain a low amount of capsaicin, one of several compounds which induce the hot sensation (pungency) in mammals. The highest concentration of capsaicin is located in the placental tissue (the pith) to which the seeds are attached.

- Turkey meat is not particularly high in tryptophan, and does not cause more drowsiness than other foods. Drowsiness after large meals such as Christmas or Thanksgiving dinner generally comes from overeating.

- Darker roasts of coffee do not always contain more caffeine than lighter roasts. When coffee is roasted, it expands and loses water. When the resultant coffee is ground and measured volumetrically, the denser lighter roasts have more coffee per cup, meaning they contain more caffeine.

- Bourbon whiskey does not have to be distilled in Kentucky. Bourbon is also distilled in states such as New York, California, Wyoming and Washington, as the legal requirement is only that it be made in the US. However, Kentucky does produce the majority of bourbon.

- Using mild soap on well-seasoned cast-iron cookware will not damage the seasoning. This is not because modern soaps are gentler than older soaps.

- Sushi does not mean raw seafood; some sushi, such as kappamaki, contains no seafood. The word refers to the vinegar-prepared rice the dish contains.

- Allspice is not a mix of spices. It is a single spice, so called because it seems to combine the flavours and scents of many spices, especially cinnamon, nutmeg, cloves and black pepper.

- Monosodium glutamate has not been found to cause headaches and other feelings of discomfort, known as "Chinese restaurant syndrome" in placebo-controlled trials. Although there are reports of MSG sensitivity among a subset of the population, this has not been demonstrated in trials.

Food and drink history

[edit]- Steak tartare was not invented by Mongol warriors who tenderized horse meat under their saddles. It is likely named after the French tartar sauce, evolving from an early 20th century French dish where the sauce was served with steaks.

- Marco Polo did not introduce pasta to Italy from China. The misconception originated as promotional material in the Macaroni Journal, a newsletter published by an association of American pasta makers.

- Spices were not used in the Middle Ages to mask the flavor of rotten meat before refrigeration. Spices were an expensive luxury item; those who could afford them could afford good meat, and there are no contemporaneous documents calling for spices to disguise the taste of bad meat.

- Catherine de' Medici's cooks did not introduce Italian foods and techniques to the French royal court, laying the foundations for the development of French haute cuisine.

- Whipped cream was not invented by François Vatel in 1661 and later named at the Château de Chantilly where it was notably served; similar recipes are attested at least a century earlier in France and England.

- Dom Pérignon did not invent champagne. Wine naturally starts to bubble after being pressed, and bubbles at the time were considered a flaw which Pérignon worked unsuccessfully to eliminate.

- Potato chips were not invented by a frustrated George Speck in response to a customer, sometimes given as Cornelius Vanderbilt, complaining that his French fries were too thick and not salty enough. Recipes for potato chips were published as early as 1817. The misconception was popularized by a 1973 advertising campaign by the St. Regis Paper Company.

- George Washington Carver was not the inventor of peanut butter. The first peanut butter related patent was filed by John Harvey Kellogg in 1895, and peanut butter was used by the Incas centuries prior to that. Carver did compile hundreds of uses for peanuts, in addition to uses for pecans, and sweet potatoes. An opinion piece by William F. Buckley Jr. may have been the source of the misconception.

- Fortune cookies are not found in Chinese cuisine, despite their presence in Chinese restaurants in the United States and other Western countries. They originated in Japan and were introduced to the US by the Japanese. In China, they are considered American, and are rare.

- Julius Caesar did not invent Caesar salad. Its creator was Caesar Cardini, an Italian-American restaurateur, in Tijuana, Mexico, in 1924.

- Hydrox is not a knock-off of Oreos. Hydrox, invented in 1908, predates Oreos by four years and was initially more popular than Oreos. The name "Hydrox" being said to sound like a laundry detergent contributed to its market decline.

- The difference between the taste of "banana-flavored" candy and a real banana is not due to the former being specifically designed to replicate the taste of Gros Michel bananas, the cultivar that dominated the American banana market before the rise of Cavendish bananas. All banana cultivars derive their flavor from a complex mix of many compounds, while a single compound, isoamyl acetate, gives banana candy its flavor. Isoamyl acetate naturally occurs in bananas as well as many other fruits and fermented beverages. It is more concentrated in Gros Michel bananas than in Cavendish bananas, but its use in candy production was due to its simple production, not any specific resemblance to a banana's flavor.

Microwave ovens

[edit]

- Microwave ovens are not tuned to any specific resonant frequency for water molecules in the food. They cook food via dielectric heating of polar molecules, notably water and fats.

- Microwave ovens do not cook food from the inside out. 2.45 GHz microwaves can only penetrate approximately 1–1.5 inches (2+1⁄2–3+3⁄4 centimeters) into most foods. The inside portions of thicker foods are mainly heated by heat conducted from the outer layers.

- The radiation produced by a microwave oven is non-ionizing, similar to visible light or radio waves. It therefore does not have the cancer risks associated with ionizing radiation such as X-rays and high-energy particles, nor does it render the food radioactive. All microwave radiation dissipates as heat. Long-term rodent studies to assess cancer risk have so far failed to identify any carcinogenicity from 2.45 GHz microwave radiation even with chronic exposure levels (i.e. large fraction of life span) far larger than humans are likely to encounter from any leaking ovens. The risk of injury from direct exposure to microwaves is not cumulative, but instead the result of a high-intensity exposure resulting in tissue burns, in much the same way that a high-intensity laser can burn.

- Microwaving food does not significantly reduce its nutritive value more than other ways of heating and may preserve it better than other cooking processes due to shorter cooking times.

Film and television

[edit]

- Ronald Reagan was never seriously considered for the role of Rick Blaine in the 1942 film Casablanca, eventually played by Humphrey Bogart. An early studio press release mentioned Reagan, but the studio already knew that Reagan was unavailable because of his upcoming military service. Indeed, the producer had always wanted Bogart for the part.

- Walt Disney Studios' Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs was not the first animated film to be feature-length. El Apóstol, a lost 1917 Argentine silent film that used cutout animation, is considered the first. The misconception comes from Snow White and the Seven Dwarves being the first feature-length film to be animated on cels.

- The 1939 film The Wizard of Oz was not the first film in color. Kinemacolor was used starting in 1902, and the first Technicolor process debuted in 1917.

Language

[edit]

- The Chinese word for "crisis" (危机) is not composed of the symbols for "danger" and "opportunity"; the first does represent danger, but the second instead means "inflection point" (the original meaning of the word "crisis"). The misconception was popularized mainly by campaign speeches by John F. Kennedy.

- The pronunciation of coronal fricatives in Spanish did not arise through imitation of a lisping king. Only one Spanish king, Peter of Castile, is documented as having a lisp, and the current pronunciation originated two centuries after his death.

- Sign languages are not the same worldwide. Aside from the pidgin International Sign, each country generally has its own native sign language, and some have more than one.

- The word "gringo" did not originate during the Mexican–American War (1846–1848) as a corruption of "Green, go home!", in reference to the green uniforms of American troops. The word originally simply meant "foreigner", and is probably a corruption of the Spanish word griego for "Greek" (along the lines of the idiom "It's Greek to me").

English language

[edit]- Irregardless is a word. It appears in numerous dictionaries along with other nonstandard, slang, or colloquial terms.

- It is permissible to end a sentence with a preposition. The supposed rule against it originated in an attempt to imitate Latin, but modern linguists agree that it is a natural and organic part of the English language. Similarly, modern style and usage manuals allow split infinitives.

- African American Vernacular English speakers do not simply replace "is" with "be" across all tenses, with no added meaning. In fact, AAVE speakers use "be" to mark a habitual grammatical aspect not explicitly distinguished in Standard English.

- "420" did not originate from the Los Angeles police or penal code for marijuana use. California Penal Code section 420 prohibits the obstruction of access to public land. The use of "420" started in 1971 at San Rafael High School, where a group of students would go to smoke at 4:20 pm.

- Xmas did not originate as a secular plan to "take Christ out of Christmas".[1] X represents the Greek letter chi, the first letter of Χριστός (Christós), "Christ" in Greek, as found in the chi-rho symbol (ΧΡ) since the 4th century. In English, "X" was first used as a scribal abbreviation for "Christ" in 1021.

- The word crap did not originate as a back-formation of British plumber Thomas Crapper's apt surname. The word crap ultimately comes from Medieval Latin crappa.

- The word fuck did not originate in the Middle Ages as an acronym. Proposed acronyms include "fornicating under consent of king" or "for unlawful carnal knowledge", used as a sign posted above adulterers in the stocks. Nor did it originate as a corruption of "pluck yew" (an idiom falsely attributed to the English for drawing a longbow). It is most likely derived from Middle Dutch or other Germanic languages, where it either meant "to thrust" or "to copulate with" (fokken in Middle Dutch), "to copulate", or "to strike, push, copulate" or "penis".[2] Either way, these variations would have been derived from the Indo-European root word -peuk, meaning "to prick".

- The expression "rule of thumb" did not originate from an English law allowing a man to beat his wife with a stick no thicker than his thumb, and there is no evidence that such a law ever existed. The expression originates from the late seventeenth century from various trades where quantities were measured by comparison to the width or length of a thumb.

- The word the was never pronounced or spelled "ye" in Old or Middle English. The confusion, seen in the common stock phrase "ye olde", derives from the use of the character thorn (þ), which in Middle English represented the sound now represented in Modern English by "th". This evolved as early printing presses substituted the word the with "yͤ", a "y" character with a superscript "e".

- The anti-Italian slur wop did not originate from an acronym for "without papers" or "without passport"; it is actually derived from the term guappo (roughly meaning thug), from the Spanish guapo.

Law, crime, and military

[edit]

- Crime rates are declining for most types of crime, beginning in the mid to late 1980s and early 1990s. In Europe, crime statistics show this is part of a broader pattern of crime decline since the late Middle Ages, with a reversal from the 1960s to the 1980s and 1990s, before the decline continued. In the United States, between 1993 and 2022, the rate of violent crime per 100,000 people fell by almost 50%, and the rate of property crime fell by more than half. The number of gun homicides also decreased.

- Despite parents of many cultures having been regarded as having the right, if not duty, to physically punish misbehaving children to teach appropriate behavior such as by spanking, many studies consistently find that corporal punishment may have the opposite effect in the long run, decreasing long-term obedience, while increasing the chances of aggressive behavior, depression, anxiety, suicide, and physical abuse. (Some alternatives.)

- Chewing gum is not punishable by caning in Singapore. Although importing and selling chewing gum has been illegal in Singapore since 1992, and corporal punishment is still an applicable penalty for certain offenses in the country, the two facts are unrelated; chewing gum-related offenses have always been only subject to fines and incarceration, and the possession or consumption of chewing gum itself is not illegal.

- Employees of the international police organization Interpol cannot conduct investigations, arrest criminals or use fake passports.[clarification needed] Interpol's role is facilitating international communication between law enforcement agencies of sovereign states.

- No cases have been proven of strangers killing or permanently injuring children by intentionally hiding poisons or sharp objects such as razor blades in candy or apples during Halloween trick-or-treating and the belief has been "thoroughly debunked". However, in at least one case, adult family members have spread this story to cover up filicide.

- There has never been a documented case of pet black cats being tortured or ritually sacrificed around Halloween. Where violent deaths of black cats have been documented around Halloween, the death has usually been ascribed to natural predators, such as coyotes, eagles, or raptors.

- It is not necessary to wait 24 hours before filing a missing person report. When there is evidence of violence or of an unusual absence, it is important to start an investigation promptly. Criminology experts say the first 72 hours in a missing person investigation are the most critical.

- Perry Mason moments, in which a person on trial for a crime is suddenly exonerated by newly introduced revelations, are exceptionally rare in real-life court proceedings, despite their ubiquity in legal drama. The vast majority of evidence is unveiled in pretrial discovery; should new revelations occur, a trial is usually stayed until both the prosecution and defense can review it.

United States

[edit]

- Undocumented immigrants in the US have substantially lower crime rates than US-born citizens. Immigrants are 60% less likely to be incarcerated than US-born citizens.

- The First Amendment to the United States Constitution generally prevents only government restrictions on the freedoms of religion, speech, press, assembly, or petition, not restrictions imposed by other entities unless they are acting on behalf of the government. Other laws may limit the ability of private businesses and individuals to restrict the speech of others.

- In the United States, a defendant may not have their case dismissed simply because they were not read their Miranda rights at the time of their arrest. Miranda warnings cover the rights of a person when they are taken into custody and then interrogated by law enforcement. If a person is not given a Miranda warning before the interrogation is conducted, statements made by them during the interrogation may not be admissible in a trial. The prosecution may still present other forms of evidence, or statements made during interrogations where the defendant was read their Miranda rights, to get a conviction.

- The United States does not require police officers to identify themselves as police in the case of a sting or other undercover work, and police officers may lie when engaged in such work. Claiming entrapment as a defense instead focuses on whether the defendant was improperly induced by undue pressure from government agents (possibly including civilians and informants acting under police direction) to commit crimes they would not have otherwise committed.

- It is not illegal in the US to shout "fire" in a crowded theater. Although this is often given as an example of speech that is not protected by the First Amendment, it is not now nor has it ever been binding law. The phrase originates from Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.'s opinion in the United States Supreme Court case Schenck v. United States in 1919, which held that the defendant's speech in opposition to the draft during World War I was not protected free speech. However, that case was not about shouting "fire" and the decision was later overturned by Brandenburg v. Ohio in 1969.

- The US Armed Forces have generally forbidden military enlistment as a form of deferred adjudication (that is, an option for convicts to avoid jail time) since the 1980s. US Navy protocols discourage the practice, while the other four branches have specific regulations against it.

- Last meal requests do not have to be fulfilled. States have various restrictions on what can be requested, up to not permitting them at all.

- Although popularly known as the "red telephone", the Moscow–Washington hotline was never a telephone line, nor were red phones used. The first implementation of the hotline used teletype equipment, which was replaced by facsimile (fax) machines in 1988. Since 2008, the hotline has been a secure computer link over which the two countries exchange email. Moreover, the hotline links the Kremlin to the Pentagon, not the White House.

- Likewise, the nuclear football, the briefcase used by presidents to launch nuclear attacks, does not contain a large red button to launch an attack. Rather, its primary use is to confirm the president's identity, and to facilitate communication with the Pentagon.

- Twinkies were not claimed to be the cause of San Francisco mayor George Moscone's and supervisor Harvey Milk's murders. In the trial of Dan White, the defense successfully argued White's diminished capacity as a result of depression. While eating Twinkies was cited as evidence of this depression, it was never claimed to be the cause of the murders.

- Neither the Mafia nor other criminal organizations regularly use or have used cement shoes to drown their victims. There are only two documented cases of this method being used in murders: one in 1964 and one in 2016 (although, in the former, the victim had concrete blocks tied to his legs rather than being enclosed in cement). The French Army did use cement shoes on Algerians killed in death flights during the Algerian War.

- Embalming is not legally required in the United States. The Federal Trade Commission passed a rule in 1984 forbidding making this claim, to prevent the funeral industry from promoting the misconception for financial gain.

Literature

[edit]- Many quotations are incorrect or attributed to people who never uttered them, and quotations from obscure or unknown authors are often attributed to more famous figures. Commonly misquoted individuals include Mark Twain, Albert Einstein, Adolf Hitler, Winston Churchill, Abraham Lincoln, William Shakespeare, Bill Gates, Steve Jobs, Confucius, Sun Tzu, and the Buddha.

- Mary Shelley's 1818 novel Frankenstein is named after the fictional scientist Victor Frankenstein, who created the sapient creature in the novel, not the creature itself, which is never named in the novel and is now usually called Frankenstein's monster. However, as later adaptations started to refer to the monster itself as Frankenstein, this usage became well-established, and some no longer regard it as erroneous.

- Ernest Hemingway did not author the flash fiction story "For sale: baby shoes, never worn". The story was not attributed to him until decades after he died.

Music

[edit]Classical music

[edit]- The musical interval tritone was not banned by the Catholic Church and was not associated with devils during the Middle Ages. Early medieval music used the tritone in Gregorian chant for certain modes. Guido of Arezzo (c. 991 – c. 1033) was the first theorist to discourage the interval.

- The minuet in G major by Christian Petzold is commonly attributed to Johann Sebastian Bach, although the piece was identified in the 1970s as a movement from a harpsichord suite by Petzold. The misconception stems from Notebook for Anna Magdalena Bach, a book of sheet music by various composers (mostly Bach) in which the minuet is found. Compositions that are doubtful as works of Bach are cataloged as "BWV Anh.", short for "Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis Anhang" ("Bach works catalogue annex"); the minuet is assigned to BWV Anh. 114.

- Listening to Mozart or classical music does not enhance intelligence (or IQ). A study from 1993 reported a short-term improvement in spatial reasoning. However, the weight of subsequent evidence supports either a null effect or short-term effects related to increases in mood and arousal, with mixed results published after the initial report in Nature.

- The "Minute Waltz" takes, on average, two minutes to play as originally written. Its name comes from the adjective minute, meaning "small", and not the noun spelled the same.

Popular music

[edit]- "Edelweiss" is not the national anthem of Austria, but an original composition created for the 1959 musical The Sound of Music. The Austrian national anthem is "Land der Berge, Land am Strome" ("Land of the Mountains, Land on the River [Danube]").

- The Beatles' 1965 appearance at Shea Stadium was not the first time that a rock concert was played at a large, outdoor sports stadium in the United States; such venues were employed by Elvis Presley in the 1950s and the Beatles themselves in 1964.

- The Monkees did not outsell the Beatles' and the Rolling Stones' combined record sales in 1967. Michael Nesmith originated the claim in a 1977 interview as a prank.

- The Rolling Stones were not performing "Sympathy for the Devil" at the 1969 Altamont Free Concert when Meredith Hunter was stabbed to death by a member of the local Hells Angels chapter that was serving as security. The stabbing occurred later as the band was performing "Under My Thumb".

- Concept albums did not begin with rock music in the 1960s. The format had already been employed by singers such as Frank Sinatra in the 1940s and 1950s.

- Cass Elliot (of The Mamas & the Papas) did not die from choking on a ham sandwich. This falsehood was initiated by her manager who wanted to avoid the implication that her death was associated with substance abuse.

- Phil Collins did not write his 1981 hit "In the Air Tonight" about witnessing someone drowning and then confronting the person in the audience who let it happen. According to Collins himself, it was about his emotions when divorcing from his first wife.

- Popular musicians are not more likely to die at the age of 27. The notion of a "27 Club" arose after the deaths, in a ten-month period, of Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, and Jim Morrison, and later the deaths of Kurt Cobain and Amy Winehouse. Statistical studies have shown that there is no scientific basis for this idea.

- The song "Puff, the Magic Dragon" is not about drugs. Both of the song's co-writers consistently and emphatically denied this interpretation throughout their lives, stating that the song is solely about the loss of childhood innocence.

Religion

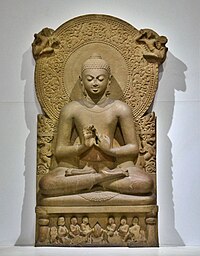

[edit]Buddhism

[edit]- The chubby, bald monk with lengthened ears who is often depicted laughing, known as the "fat Buddha" or "laughing Buddha" in the West, is not the actual Buddha, but a 10th-century Chinese Buddhist folk hero by the name of Budai. The historical Buddha, Siddhartha Gautama, who lived in the 5th century BC, is most often depicted in normal weight and concentrated in meditation.

- Buddha is not a god ("deva").[3]

Christianity

[edit]- Jesus was most likely not born on December 25, when his birth is traditionally celebrated as Christmas. It is more likely that his birth was in either the season of spring or perhaps summer. Although the Common Era ostensibly counts the years since the birth of Jesus, it is unlikely that he was born in either AD 1 or 1 BC, as such a numbering system would imply. Modern historians estimate a date closer to between 6 BC and 4 BC.

- The Bible does not say that exactly three magi came to visit the baby Jesus, nor that they were kings, or rode on camels, or that their names were Caspar, Melchior, and Balthazar, nor what color their skin was.[citation needed] Three magi are inferred because three gifts are described, but the Bible says only that there was more than one magus.

- The idea that Mary Magdalene was a prostitute before she met Jesus is not found in the Bible or in any of the other earliest Christian writings. It has been a disputed doctrine in several theological traditions whether Mary Magdalene, Mary of Bethany (who anoints Jesus' feet in John 11:1–12), and the unnamed "sinful woman" who anoints Jesus' feet in Luke 7:36–50 were the same woman.

- Paul the Apostle's name was not changed from Saul. He was born a Jew, with Roman citizenship inherited from his father, and thus carried both a Hebrew and a Greco-Roman name from birth, as mentioned by Luke in Acts 13:9: "...Saul, who also is called Paul...".

- The Roman Catholic dogma of the Immaculate Conception is unrelated to the Christian doctrine that Mary conceived and gave birth to Jesus while remaining a virgin. The Immaculate Conception is the belief that Mary was free of original sin from the moment of her own conception by her parents, Joachim and Anne. A less common mistake is to think that the Immaculate Conception means that Mary herself was conceived without sexual intercourse.

- Roman Catholic dogma does not say that the pope is either sinless (as is commonly believed among non-Catholic Christians) or always infallible. Catholic dogma since 1870 does state that a divine revelation by the pope (generally called ex cathedra) is free from error, but it does not hold that he is always free from error, even when speaking in his official capacity.

- Members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) no longer practice polygamy. The Church excommunicates any members who practice polygamy within the organization. Some Mormon fundamentalist sects do practice polygamy.

- The First Council of Nicaea did not establish the books of the Bible. The Old Testament had likely already been established by Hebrew scribes before Christ. The development of the New Testament canon was mostly completed in the third century before the Nicaea Council was convened in 325; it was finalized, along with the deuterocanon, at the Council of Rome in 382.

- Constantine the Great did not make Christianity the official religion of the Roman Empire. While he was the first Christian emperor and promoted religious tolerance with the Edict of Milan, Christianity was not declared the official religion of the Roman Empire until 380 AD, some 43 years after Constantine's death.

- The Seven Deadly Sins are never listed in the Bible. The concept originated with Tertullian, and originally consisted of nine vices. This was later reduced to seven by Gregory I.

Islam

[edit]- The burqa (also transliterated as burka or burkha) is often confused with other types of head-wear worn by Muslim women, particularly the niqāb and the hijab. A burqa covers the body, head, and face, with a mesh grille to see through. A niqab covers the hair and face, excluding the eyes. A hijab covers the hair and chest but not the face.

- Not all Muslim women wear face or head coverings.

- A fatwa is a generally non-binding legal opinion issued by an Islamic scholar under Islamic law; it is therefore commonplace for fatawa from different authors to disagree. The misconception that it is a death sentence stems from a decree issued by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini of Iran in 1989 where he said that the author Salman Rushdie had earned a death sentence for blasphemy. It is debated whether this was a fatwa.

- The word jihad does not always mean 'holy war'; its literal meaning in Arabic is 'struggle'. While there is such a thing as jihad by the sword, jihad can be any spiritual or moral effort or struggle, such as seeking knowledge, putting others before oneself, and inviting others to Islam.

- The Quran does not promise martyrs 72 virgins in heaven. It does mention that virgin female companions, houri, are given to all people, martyr or not, in heaven, but no number is specified. The source for the 72 virgins is a hadith in Sunan al-Tirmidhi by Imam Tirmidhi. Hadiths are sayings and acts of Muhammad as reported by others, not part of the Quran itself.

Judaism

[edit]

- The forbidden fruit mentioned in the Book of Genesis is never identified as an apple, as widely depicted in Western art. The original Hebrew texts mention only fruit.

- While tattoos are forbidden by the Book of Leviticus, Jews with tattoos are not barred from being buried in a Jewish cemetery, just as violators of other prohibitions are not barred, as is commonly believed among American Jews.

Sports

[edit]- Artificial turf is not maintenance free. It requires regular maintenance, such as raking and patching, to keep it functional and safe.

- The name golf is not an acronym for "Gentlemen Only, Ladies Forbidden". It may have come from the Dutch word kolf or kolve, meaning "club",

- The black belt in martial arts does not necessarily indicate expert level. It was introduced for judo in the 1880s to indicate competency at all of the basic techniques of the sport. Promotion beyond 1st dan (the first black belt rank) varies among different martial arts.

- The use of triangular corner flags in English football is not a privilege reserved for those teams that have won an FA Cup in the past, as depicted in a scene in the film Twin Town. The Football Association's rules are silent on the subject, and the decision over what shape flag to use has been up to the individual club's groundskeepers.

- India did not withdraw from the 1950 FIFA World Cup because their squad wanted to play barefoot. In reality, India withdrew because the country's managing body, the All India Football Federation (AIFF), was insufficiently prepared for the team's participation.

Video games

[edit]- There is no definitive proof that violent video games cause people to become violent. Some studies have found no link between aggression and violent video games, and the popularity of gaming has coincided with a decrease in youth violence. The moral panic surrounding video games in the 1980s through to the 2020s, alongside several studies and incidents of violence and legislation in many countries, likely contributed to proliferating this idea.

- The so-called "Nuclear Gandhi" glitch, in which peaceful leader Mahatma Gandhi would become unusually aggressive if democracy was adopted, did not exist in either the original Civilization game or Civilization II. The games' designer Sid Meier attributed the origins of the rumor to both a TV Tropes thread and a Know Your Meme entry, while Reddit and a Kotaku article helped popularize it. Gandhi's supposed behavior did appear in the 2010 Civilization V as a reference to the legend.

- The Japanese government did not pass a law banning Square Enix from releasing the Dragon Quest games on weekdays due to it causing too many schoolchildren to cut class. This rule is self-imposed by the developers themselves.

- The release of Space Invaders in 1978 did not cause a shortage of ¥100 coins in Japan. An advertising campaign by Taito and an erroneous 1980 article in New Scientist are the sources of this claim.

History

[edit]View full version with citations

Ancient history

[edit]- The Pyramids of Egypt were not constructed with slave labor. Archaeological evidence shows that the laborers were a combination of skilled workers and poor farmers working in the off-season with the participants paid in high-quality food and tax exemptions. The idea that slaves were used originated with Herodotus, and the idea that they were Israelites arose centuries after the pyramids were constructed.

- Galleys in ancient times were not commonly operated by chained slaves or prisoners, as depicted in films such as Ben Hur, but by paid laborers or soldiers, with slaves used only in times of crisis, in some cases even gaining freedom after the crisis was averted. Ptolemaic Egypt was a possible exception. Other types of vessels, such as Roman merchant vessels, were manned by slaves, sometimes even with slaves as ship's master.

- Tutankhamun's tomb is not inscribed with a curse on those who disturb it. This was a media invention of 20th-century tabloid journalists.

- The Minoan civilization was not destroyed by the eruption of Thera and was not the inspiration for Plato's parable of Atlantis.

The ancient Romans did not use the Roman salute depicted in The Oath of the Horatii (1784). - The ancient Greeks did not use the word "idiot" (Ancient Greek: ἰδιώτης, romanized: idiṓtēs) to disparage people who did not take part in civic life. An ἰδιώτης was simply a private citizen as opposed to a government official. The word also meant any sort of non-expert or layman, then later someone uneducated or ignorant, and much later to mean stupid or mentally deficient.

Ancient Rome

[edit]- The so-called Roman salute, in which the arm is fully extended forwards or diagonally with palm down and fingers touching, was not used in ancient Rome. The gesture was first associated with ancient Rome in the 1784 painting The Oath of the Horatii by the French artist Jacques-Louis David, which inspired later salutes, most notably the Nazi salute.

- Wealthy Ancient Romans did not use rooms called vomitoria to purge food during meals so they could continue eating and vomiting was not a regular part of Roman dining customs. A vomitorium of an amphitheatre or stadium was a passageway allowing quick exit at the end of an event.

- Scipio Aemilianus did not sow salt over the city of Carthage after defeating it in the Third Punic War.

- Julius Caesar was not born via caesarean section. Such a procedure would have been fatal to the mother at the time, and Caesar's mother was still alive when he was 45 years old.

Middle Ages

[edit]Europe

[edit]- The Middle Ages were not "a time of ignorance, barbarism and superstition"; the Church did not place religious authority over personal experience and rational activity; and the term "Dark Ages" is rejected by modern historians.

- While modern life expectancies are much higher than those in the Middle Ages and earlier, adults in the Middle Ages did not die in their 30s on average. That was the life expectancy at birth, which was skewed by high infant and adolescent mortality. The life expectancy among adults was much higher; a 21-year-old man in medieval England, for example, could expect to live to the age of 64. However, in various places and eras, life expectancy was noticeably lower. For example, monks often died in their 20s or 30s.

- In the tale of King Canute and the tide, the king did not command the tide to reverse in a fit of delusional arrogance. According to the story, his intent was to prove a point that no man is all-powerful, and that all people must bend to forces beyond their control, such as the tides.

- There is no evidence that iron maidens were used for torture, or even yet invented, in the Middle Ages. Instead they were pieced together in the 18th century from several artifacts found in museums, arsenals and the like to create spectacular objects intended for commercial exhibition.

- Spiral staircases in castles were not designed in a clockwise direction to hinder right-handed attackers. While clockwise spiral staircases are more common in castles than anti-clockwise, they were even more common in medieval structures without a military role, such as religious buildings.

- The plate armor of European soldiers did not stop soldiers from moving around or necessitate a crane to get them into a saddle. They needed to be able to fight on foot in case they could not ride their horse and could mount and dismount without help. However, armor used in tournaments in the late Middle Ages was significantly heavier than that used in warfare.

- Whether chastity belts, devices designed to prevent women from having sexual intercourse, were invented in medieval times is disputed by modern historians. Most existing chastity belts are now thought to be deliberate fakes from the 19th century.

- Medieval European scholars did not believe the Earth was flat. Scholars have known the Earth is spherical since at least the sixth century BCE.

- Medieval cartographers did not regularly write "here be dragons" on their maps. The only maps from this era that have the phrase inscribed on them are the Hunt-Lenox Globe and the Ostrich Egg Globe, next to a coast in Southeast Asia for both of them. Maps in this period did occasionally have illustrations of mythical or real animals.

- Christopher Columbus' efforts to obtain support for his voyages were not hampered by belief in a flat Earth, but by valid worries that the East Indies were farther than he realized. In fact, Columbus grossly underestimated the Earth's circumference because of two calculation errors. The myth that Columbus proved the Earth was round was propagated by authors like Washington Irving in A History of the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus.

- Columbus was not the first European to visit the Americas: Leif Erikson, and possibly other Vikings before him, explored Vinland, an area of coastal North America. Ruins at L'Anse aux Meadows prove that at least one Norse settlement was built in Newfoundland, confirming a story in the Saga of Erik the Red.

Vikings

[edit]- There is no evidence that Viking warriors wore horns on their helmets; this would have been impractical in battle.

- Vikings did not drink out of the skulls of vanquished enemies. This was based on a mistranslation of the skaldic poetic use of ór bjúgviðum hausa (branches of skulls) to refer to drinking horns.

- Vikings did not name Iceland "Iceland" as a ploy to discourage oversettlement. According to the Sagas of Icelanders, Hrafna-Flóki Vilgerðarson saw icebergs on the island when he traveled there, and named the island after them. Popular legend holds that Greenland was named in the hopes of attracting settlers.

Early modern

[edit]- The Mexica people of the Aztec Empire did not mistake Hernán Cortés and his landing party for gods during Cortés' conquest of the empire. This notion came from Francisco López de Gómara, who never went to Mexico and concocted the myth while working for the retired Cortés in Spain years after the conquest.

- The elite of the Dutch Golden Age wore black clothes primarily as a status symbol rather than out of Puritan self-restraint. The clothes attracted status from the difficulty of the dyeing process and the cost of elaborate embellishments.

- Shah Jahan, the Indian Mughal Emperor who commissioned the Taj Mahal, did not cut off the hands of the rumored 40,000 workers or lead designers so as to not allow the construction of another monument more beautiful than the Taj Mahal. This is an urban myth that goes back to the 1960s.

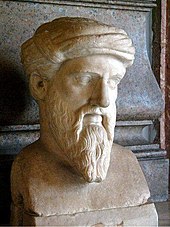

- The story that Isaac Newton was inspired to research the nature of gravity when an apple fell on his head is almost certainly apocryphal. All Newton himself ever said was that the idea came to him as he sat "in a contemplative mood" and "was occasioned by the fall of an apple".

- Marie Antoinette did not say "let them eat cake" when she heard that the French peasantry were starving due to a shortage of bread. The phrase was first published in Rousseau's Confessions, written when Marie Antoinette was only nine years old and not attributed to her, just to "a great princess". It was first attributed to her in 1843.

North America

[edit]- The early settlers (commonly known as Pilgrims) of the Plymouth Colony in North America usually did not wear all black, and their capotains (hats) did not include buckles. Instead, their fashion was based on that of the late Elizabethan era. The traditional image was formed in the 19th century when buckles were a kind of emblem of quaintness. (The Puritans, who settled in the adjacent Massachusetts Bay Colony shortly after the Pilgrims arrived in Plymouth, did frequently wear all black.)

- People accused of witchcraft were not burned at the stake during the Salem witch trials. Of the accused, nineteen people convicted of witchcraft were executed by hanging, at least five died in prison, and one man was pressed to death by stones while trying to extract a confession from him.

- George Washington did not have wooden teeth. His dentures were made of lead, gold, hippopotamus ivory, the teeth of various animals, including horse and donkey teeth, and human teeth, possibly bought from slaves or poor people. Because ivory teeth quickly became stained, they may have had the appearance of wood to observers.

- The signing of the United States Declaration of Independence did not occur on July 4, 1776. After the Second Continental Congress voted to declare independence on July 2, the final language of the document was approved on July 4, and it was printed and distributed on July 4–5. However, the actual signing occurred on August 2, 1776.

- Benjamin Franklin did not propose that the wild turkey be used as the symbol for the United States instead of the bald eagle. While he did serve on a commission that tried to design a seal after the Declaration of Independence, his proposal was an image of Moses. His objections to the eagle as a national symbol and preference for the turkey were stated in a 1784 letter to his daughter in response to the Society of the Cincinnati's use of the former; he never expressed that sentiment publicly.

- There was never a bill to make German the official language of the United States that was defeated by one vote in the House of Representatives, nor has one been proposed at the state level. In 1794, a petition from a group of German immigrants was put aside on a procedural vote of 42 to 41, that would have had the government publish some laws in German. This was the basis of the Muhlenberg legend, named after the Speaker of the House at the time, Frederick Muhlenberg, who was of German descent and abstained from this vote.

Modern

[edit]

- Napoleon Bonaparte was not especially short for a Frenchman of his time. He was the height of an average French male in 1800, but short for an aristocrat or officer. After his death in 1821, the French emperor's height was recorded as 5 feet 2 inches in French feet, which in English measurements is 5 feet 7 inches (1.70 m).

- The nose of the Great Sphinx of Giza was not shot off by Napoleon's troops during the French campaign in Egypt (1798–1801); it has been missing since at least the 10th century.

- Cinco de Mayo is not Mexico's Independence Day, but the celebration of the Mexican Army's victory over the French in the Battle of Puebla on May 5, 1862. Mexico's Declaration of Independence from Spain in 1810 is celebrated on September 16.

- Victorian-era doctors did not invent the vibrator to cure female "hysteria" by triggering orgasm.

- Albert Einstein did not fail mathematics classes in school. Einstein remarked, "I never failed in mathematics.... Before I was fifteen I had mastered differential and integral calculus." Einstein did, however, fail his first entrance exam into the Swiss Federal Polytechnic School (ETH) in 1895, when he was two years younger than his fellow students, but scored exceedingly well in the mathematics and science sections, and then passed on his second attempt.

- Alfred Nobel did not omit mathematics in the Nobel Prize due to a rivalry with mathematician Gösta Mittag-Leffler, as there is little evidence the two ever met, nor was it because Nobel's spouse had an affair with a mathematician, as Nobel was never married. The more likely explanation is that Nobel believed mathematics was too theoretical to benefit humankind, as well as his personal lack of interest in the field. (See also: Nobel Prize controversies)

- Grigori Rasputin was not assassinated by being fed cyanide-laced cakes and wine, shot multiple times, and then thrown into the Little Nevka river when he survived the former two. A contemporary autopsy reported that he was just killed with gunshots. A sensationalized account from the memoirs of co-conspirator Prince Felix Yusupov is the only source of this story.

- The Italian dictator Benito Mussolini did not "make the trains run on time". Much of the repair work had been performed before he and the Fascist Party came to power in 1922. Moreover, the Italian railways' supposed adherence to timetables was more propaganda than reality.

- There is no evidence of Polish cavalry mounting a brave but futile charge against German tanks using lances and sabers during the German invasion of Poland in 1939. This story may have originated from German propaganda efforts following the charge at Krojanty.

- The Nazis did not use the term "Nazi" to refer to themselves. The full name of the Nazi Party was Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (National Socialist German Workers' Party), and members referred to themselves as Nationalsozialisten (National Socialists) or Parteigenossen (party comrades). The term "Nazi" was in use prior to the rise of the Nazis as a colloquial and derogatory word for a backwards farmer or peasant. Opponents of the National Socialists abbreviated their name as "Nazi" for derogatory effect and the term was popularized by German exiles outside of Germany.

- During the occupation of Denmark by the Nazis during World War II, King Christian X of Denmark did not thwart Nazi attempts to identify Jews by wearing a yellow star himself. Jews in Denmark were never forced to wear the Star of David. The Danish resistance did help most Jews flee the country before the end of the war.

- Not all skinheads are white supremacists; many skinheads identify as left-wing or apolitical, and many oppose racism, such as the Skinheads Against Racial Prejudice. Originating from the 1960s British working class, many of its initial adherents were black and West Indian; it became associated with white supremacy in the 1970s as a result of far-right groups like the National Front recruiting from the subculture for grassroot support.

United States

[edit]

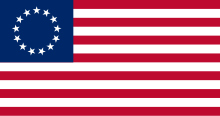

- Betsy Ross did not design or make the first official U.S. flag, despite it being widely known as the Betsy Ross flag. The claim was first made by her grandson a century later.

- Abraham Lincoln did not write his Gettysburg Address speech on the back of an envelope on his train ride to Gettysburg. The speech was substantially complete before Lincoln left Washington for Gettysburg.

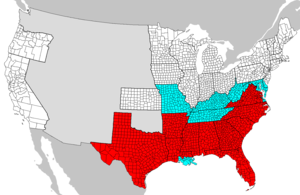

- The Emancipation Proclamation did not free all slaves in the United States; the Proclamation applied in the ten states that were still in rebellion in 1863, and thus did not cover the nearly five hundred thousand slaves in the slaveholding border states that had not seceded. (See also: Abolition of slavery timeline)

- Likewise, the June 19, 1865 order celebrated annually as "Juneteenth" only applied in Texas, not the United States at large. The Thirteenth Amendment, ratified and proclaimed in December 1865, was the article that banned slavery nationwide except as punishment for a crime.

- The Alaska Purchase was generally viewed as positive or neutral in the United States, both among the public and the press. The opponents of the purchase who characterized it as "Seward's Folly", alluding to William H. Seward, the Secretary of State who negotiated it, represented a minority opinion at the time.

- Cowboy hats were not initially popular in the Western American frontier, with derby or bowler hats being the typical headgear of choice. Heavy marketing of the Stetson "Boss of the Plains" model in the years following the American Civil War was the primary driving force behind the cowboy hat's popularity, with its characteristic dented top not becoming standard until near the end of the 19th century.

- The Great Chicago Fire of 1871 was not caused by Mrs. O'Leary's cow kicking over a lantern. A newspaper reporter later admitted to having invented the story to make colorful copy.

- There is no evidence that Frederic Remington, on assignment to Cuba in 1897, telegraphed William Randolph Hearst: "There will be no war. I wish to return," nor that Hearst responded: "Please remain. You furnish the pictures, and I'll furnish the war". The anecdote was originally included in a book by James Creelman and probably never happened.

- The electrocution of Topsy the Elephant was not an anti-alternating current demonstration organized by Thomas A. Edison during the war of the currents. Edison was never at Luna Park, and the electrocution of Topsy took place ten years after the war of currents. This myth may stem from the fact that the recording of the event was produced by the Edison film company.

- Mary Mallon, known as "Typhoid Mary", testified at her 1909 trial that she did not believe she was contagious while an asymptomatic carrier of the bacteria Salmonella typhi. She later infected many others, while using fake names and evading health authorities.

- Immigrants' last names were not Americanized (voluntarily, mistakenly, or otherwise) upon arrival at Ellis Island. Officials there kept no records other than checking ship manifests created at the point of origin, and there was simply no paperwork that would have let them recast surnames, let alone any law. At the time in New York, anyone could change the spelling of their name simply by using that new spelling. These names are often referred to as an "Ellis Island Special".

- Prohibition did not make drinking alcohol illegal in the United States. The Eighteenth Amendment and the subsequent Volstead Act prohibited the production, sale, and transport of "intoxicating liquors" within the United States, but their possession and consumption were never outlawed.

- Distraught stockbrokers did not jump to their deaths in large numbers after the Wall Street Crash of 1929. Although extensively reported by the news media, the phenomenon was limited in number and the overall suicide rate following the 1929 crash did not increase.

- There was no widespread outbreak of panic across the United States in response to Orson Welles' 1938 radio adaptation of H.G. Wells' The War of the Worlds. Only a very small share of the radio audience was listening to it, but newspapers, being eager to discredit radio as a competitor for advertising, played up isolated reports of incidents and increased emergency calls. Both Welles and CBS, which had initially reacted apologetically, later came to realize that the myth benefited them and actively embraced it in later years.

- American pilot Kenneth Arnold did not coin the term flying saucer; he did not use that phrase when describing his 1947 UFO sighting at Mount Rainier, Washington. The East Oregonian, the first newspaper to report on the incident, merely quoted him as saying the objects "flew like a saucer" and were "flat like a pie pan".

- U.S. Senator George Smathers never gave a speech to a less-educated audience describing his opponent, Claude Pepper, as an "extrovert" whose sister was a "thespian", in the apparent hope they would confuse them with similar-sounding words like "pervert" and "lesbian". Smathers offered US$10,000 to anyone who could prove he had made the speech; it was never claimed.

- Dwight D. Eisenhower did not order the construction of the Interstate Highway System for the sole purpose of evacuating cities in the event of nuclear warfare. While military motivations were present, the primary motivations were civilian.

- Rosa Parks was not sitting in the front ("white") section of the bus during the event that made her famous and incited the Montgomery bus boycott. Rather, she was sitting in the front of the back ("colored") section of the bus, where African Americans were expected to sit, and rejected an order from the driver to vacate her seat in favor of a white passenger when the "white" section of the bus had become full.

- The African-American intellectual and activist W. E. B. Du Bois did not renounce his U.S. citizenship while living in Ghana shortly before his death. In early 1963, his membership in the Communist Party and support for the Soviet Union led the U.S. State Department to refuse to renew his passport while he was already in Ghana. After leaving the embassy, he stated his intention to renounce his citizenship in protest, but while he took Ghanaian citizenship, he never actually renounced his American citizenship.

- US President John F. Kennedy's words "Ich bin ein Berliner" are standard German for "I am a Berliner (citizen of Berlin)." It is not true that by using the indefinite article ein, he changed the meaning of the sentence from the intended "I am a citizen of Berlin" to "I am a Berliner", a Berliner being a type of German pastry, similar to a jelly doughnut, amusing Germans. Furthermore, the pastry, which is known by many names in Germany, was not then — nor is it now — commonly called "Berliner" in the Berlin area.

- When Kitty Genovese was murdered outside her apartment in 1964, there were not 38 neighbors standing idly by and watching who failed to call the police until after she was dead, as was initially reported to widespread public outrage that persisted for years and even became the basis of a theory in social psychology. In fact, witnesses only heard brief portions of the attack and did not realize what was occurring, and only six or seven actually saw anything. One witness, who had called the police, said when interviewed by officers at the scene, "I didn't want to get involved", an attitude later attributed to all the neighbors.

- While it was praised by one architectural magazine before it was built as "the best high apartment of the year", the Pruitt–Igoe housing project in St. Louis, Missouri never won any awards for its design. The architectural firm that designed the buildings did win an award for an earlier St. Louis project, which may have been confused with Pruitt–Igoe.

- There is little contemporary documentary evidence for the notion that US Vietnam veterans were spat upon by anti-war protesters upon return to the United States. This belief was detailed in some biographical accounts and was later popularized by films such as Rambo.

- Women did not burn their bras outside the Miss America contest in 1969 as a protest in support of women's liberation. They did symbolically throw bras in a trash can, along with other articles seen as emblematic of women's position in American society such as mops, make-up, and high-heeled shoes. The myth of bra burning came when a journalist hypothetically suggested that women may do so in the future, as men of the era burned their draft cards.

- The American space program in the 1960s never had a wide base of public support and did not unify America. Belief that the Apollo program was worth the time and money invested peaked at 51% for a few months after the 1969 Apollo 11 moon landing, and otherwise had fluctuated between 35–45% support.

- Despite popularizing the phrase "drinking the Kool-Aid", Kool-Aid was not used for the potassium cyanide-fruit punch mix ingested as part of the Jonestown massacre. A similar product, Flavor-Aid, was used.

Science, technology and mathematics

[edit]View full version with citations

Astronomy and spaceflight

[edit]- There is no scientific evidence that the motion of stars, planets, and other celestial bodies influences the fates of humans, and astrology has repeatedly been shown to have no explanatory power in predicting future events.

- Astronauts in orbit have the sensation of being weightless because they are in free fall around the Earth, not because they are so far away from the Earth that its gravitational pull is negligible. For example, on the International Space Station the Earth's gravity is nearly 90% as strong as at the surface. Objects orbiting in space would not remain in orbit if not for the gravitational force, and gravitational fields extend even into the depths of intergalactic space.

- The dark (far) side of the Moon receives about the same amount of light from the Sun as the near side. It is called "dark" not because it never receives light but because it had never been seen until humans sent spacecraft around the Moon, since the same side of the Moon always faces the Earth due to tidal locking.

- Black holes have the same gravitational effects as any other equal mass in their place. They will draw objects nearby towards them, just as any other celestial body does, except at very close distances to the black hole, comparable to its Schwarzschild radius. If, for example, the Sun were replaced by a black hole of equal mass, the orbits of the planets would be essentially unaffected. A stellar mass black hole can pull in a substantial inflow of surrounding matter, but only if the star from which it formed was already doing so.

- Seasons are not caused by the Earth being closer to the Sun in the summer than in the winter, but by the effects of Earth's 23.4-degree axial tilt. Each hemisphere is tilted towards the Sun in its respective summer (July in the Northern Hemisphere and January in the Southern Hemisphere), resulting in longer days and more direct sunlight, with the opposite being true in the winter. Earth reaches the point in its orbit closest to the Sun in January, and it reaches the point farthest from the Sun in July, so the slight contribution of orbital eccentricity opposes the temperature trends of the seasons in the Northern Hemisphere. Orbital eccentricity can influence temperatures, but on Earth, this effect is small and is more than counteracted by other factors.

- When a meteor or spacecraft enters the atmosphere, the heat of entry is not primarily caused by friction, but by adiabatic compression of air in front of the object.

- Egg balancing is possible on every day of the year, not just the vernal equinox, and there is no relationship between any astronomical phenomenon and the ability to balance an egg.

- The Fisher Space Pen was not commissioned by NASA at a cost of millions of dollars, while the Soviets used pencils. It was independently developed by Paul C. Fisher, founder of the Fisher Pen Company, with $1 million of his own funds. NASA tested and approved the pen for space use, then purchased 400 pens at $6 per pen. The Soviet Union subsequently also purchased the Space Pen for its Soyuz spaceflights.

- Tang, Velcro, and Teflon were not spun off from technology originally developed by NASA for spaceflight, though many other products (such as memory foam and space blankets) were.

- The Sun is not yellow; rather, it emits light across the full spectrum of visible colors, and this combined light appears white when outside of Earth's atmosphere. Earth's atmosphere scatters shorter wavelengths of light, particularly blues and violets, more than longer wavelengths like reds and yellows, and this scattering is why the Sun appears yellow during the day or orange or red during sunrise and sunset.

- The Great Wall of China is not the only human-made object visible from space or from the Moon. None of the Apollo astronauts reported seeing any specific human-made object from the Moon, and even Earth-orbiting astronauts can see it only with magnification. City lights, however, are easily visible on the night side of Earth from orbit.

- The Big Bang model does not fully explain the origin of the universe. It does not describe how energy, time, and space were caused, but rather it describes the emergence of the present universe from an ultra-dense and high-temperature initial state.

Biology

[edit]Mammals

[edit]- Old elephants near death do not leave their herd to go to an "elephants' graveyard" to die.

- Bulls are not enraged by the color red, used in capes by professional bullfighters. Cattle are dichromats, so red does not stand out as a bright color. It is not the color of the cape, but the perceived threat by the bullfighter that incites it to charge.

- Domestic cats' behavioral and personality traits cannot be predicted from their coat color. Rather, these traits depend on a complex interplay between genetic and environmental factors.

- Not all cats are attracted and intoxicated by catnip, which only affects about two thirds of them. Alternatives exist, such as valerian root and leaves.

- Lemmings do not engage in mass suicidal dives off cliffs when migrating. The scenes of lemming suicides in the 1958 Disney documentary film White Wilderness, which popularized this idea, were completely fabricated. The lemmings in the film were actually purchased from Inuit children, transported to the filming location in Canada and repeatedly shoved off a nearby cliff by the filmmakers to create the illusion of a mass suicide. The misconception itself is much older, dating back to at least the late 19th century, though its exact origins are uncertain.

- Dogs do not sweat by salivating. Dogs actually do have sweat glands and not only on their tongues; they sweat mainly through their footpads. However, dogs do primarily regulate their body temperature through panting. (See also: Dog Anatomy § Temperature regulation)

- Dogs do not consistently age seven times as quickly as humans. Aging in dogs varies widely depending on the breed; certain breeds, such as giant dog breeds and English bulldogs, have much shorter lifespans than average. Most dogs reach adolescence by one year old; smaller and medium-sized breeds begin to age more slowly in adulthood.

- The phases of the Moon have no effect on the vocalizations of wolves, and wolves do not howl at the Moon. Wolves howl to assemble the pack usually before and after hunts, to pass on an alarm particularly at a den site, to locate each other during a storm, while crossing unfamiliar territory, and to communicate across great distances.

- There is no such thing as an "alpha" in a wolf pack. An early study that coined the term "alpha wolf" had only observed unrelated adult wolves living in captivity. In the wild, wolf packs operate like families: parents are in charge until the young grow up and start their own families, and younger wolves do not overthrow an "alpha" to become the new leader.

- Bats are not blind. While about 70% of bat species, mainly in the microbat family, use echolocation to navigate, all bat species have eyes and are capable of sight. In addition, almost all bats in the megabat or fruit bat family cannot echolocate and have excellent night vision.

- Tomato juice and sauce are ineffective at neutralizing the odor of a skunk. Effective treatments for skunk odor involve artificial compounds rather than household remedies.

- Porcupines do not shoot their quills. They can detach, and porcupines will deliberately back into attackers to impale them, but their quills do not project.

- Mice do not have a special appetite for cheese, and will eat it only for lack of better options; they actually favor sweet, sugary foods. The myth may have come from the fact that before the advent of refrigeration, cheese was usually stored outside and was therefore an easy food for mice to reach.

- The hippopotamus does not produce pink milk, nor does it sweat blood. The skin secretions of the hippopotamus are red due to the presence of hipposudoric acid, a red pigment which acts as a natural sunscreen, and is neither sweat nor blood. It does not affect the color of their milk, which is white or beige.

- Rabbits are not especially partial to carrots. Their diet in the wild primarily consists of dark green vegetables such as grasses and clovers, and excessive carrot consumption is unhealthy for them due to containing high levels of sugar. This misconception originated from Bugs Bunny cartoons, whose carrot-chomping habit was meant as a reference to the character played by Clark Gable in It Happened One Night.

Birds

[edit]- A human touching or handling eggs or baby birds will not cause the adult birds to abandon them. The same is generally true for other animals having their young touched by humans as well, with the possible exception of rabbits (as rabbits will sometimes abandon their nest after an event they perceive as traumatizing).

- Eating rice, yeast, or Alka-Seltzer does not cause birds to explode and is rarely fatal. Birds can flatulate and regurgitate to expel gas, and some birds even include wild rice as part of their diet. The misconception has often led to weddings using millet, confetti, or other materials to shower the newlyweds as they leave the ceremony, instead of the throwing of rice that is traditional in some places.

- The bold, powerful cry commonly associated with the bald eagle in popular culture is actually that of a red-tailed hawk. Bald eagle vocalizations are much softer and chirpier, and bear far more resemblance to the calls of gulls.

- Ostriches do not stick their heads in the sand to hide from enemies or to sleep. This misconception's origins are uncertain but it was probably popularized by Pliny the Elder (23–79 CE), who wrote that ostriches "imagine, when they have thrust their head and neck into a bush, that the whole of their body is concealed".

- A duck's quack actually does echo, although the echo may be difficult to hear for humans under some circumstances. Despite this, a British panel show compiling interesting facts has been given the name Duck Quacks Don't Echo.

- Despite the saying "dumb as dodo," the dodo's intelligence was above average for an avian, as it was a member of the family Columbidae (pigeons). The perceived stupidity of the dodo, a medium-sized flightless bird that was native to Mauritius, is due to naivety and passivity from living in isolation without significant predators.

- Many believe that the dodo was hunted to extinction by European settlers due to its high culinary value. However, the dodo's meat was stated to be inedible by historical accounts, as one of its early names given by the Dutch was Walghvoghel (Tasteless bird). The dodo's decline was caused more by predation of their eggs from invasive species as opposed to direct predation from humans like the passenger pigeon or woolly mammoth.'

- Sixty common starlings were released in 1890 into New York's Central Park by Eugene Schieffelin, but there is no evidence that he was trying to introduce every bird species mentioned in the works of William Shakespeare into North America. This claim has been traced to an essay in 1948 by naturalist Edwin Way Teale, whose notes appear to indicate that it was speculation.

Other vertebrates

[edit]- Contrary to the allegorical story about the boiling frog, frogs die immediately when cast into boiling water, rather than leaping out; furthermore, frogs will attempt to escape cold water that is slowly heated past their critical thermal maximum.

- The memory span of goldfish is much longer than just a few seconds. It is up to a few months long.

- Sharks can get cancer. The misconception that sharks do not get cancer was spread by the 1992 book Sharks Don't Get Cancer, which was used to sell extracts of shark cartilage as cancer prevention treatments. Reports of carcinomas in sharks exist, and current data does not support any conclusions about the incidence of tumors in sharks.

- Great white sharks do not mistake human divers for seals or other pinnipeds. When attacking pinnipeds, the shark surfaces quickly and attacks violently. In contrast, attacks on humans are slower and less violent: the shark charges at a normal pace, bites, and swims off. Great white sharks have efficient eyesight and color vision; the bite is not predatory, but rather for identification of an unfamiliar object.

- Snake jaws cannot unhinge. The posterior end of the lower jaw bones contains a quadrate bone, allowing jaw extension. The anterior tips of the lower jaw bones are joined by a flexible ligament allowing them to bow outwards, increasing the mouth gape.

- The Pacific tree frog and the Baja California chorus frog are some of the only frog species that make a "ribbit" sound. The misconception that all frogs, or at least all those found in North America, make this sound comes from its extensive use in Hollywood films.

- There is no credible evidence that the candiru, a South American parasitic catfish, can swim up a human urethra if one urinates in the water in which it lives. The sole documented case of such an incident, written in 1997, has been heavily criticized upon peer review, and this phenomenon is now largely considered a myth.

- Pacus, South American fish related to piranhas, do not attack or feed on human testicles. This myth originated from a misinterpreted joke in a 2013 report of a pacu being found in Øresund, the strait between Sweden and Denmark, which claimed that the fish ate "nuts".

- Piranhas do not eat only meat but are omnivorous, and they only swim in schools to defend themselves from predators and not to attack. They very rarely attack humans, only when under stress and feeling threatened, and even then, bites typically only occur on hands and feet.

- The skin of a chameleon is not adapted solely for camouflage purposes, nor can a chameleon change its skin color to match any background. Chameleons usually change color for social signaling, based on their mood, and for heat regulation. The use in social signaling may be to display bright colors for only brief periods of time to avoid increased visibility to predators.

Invertebrates

[edit]- Not all earthworms become two worms when cut in half. Only a limited number of earthworm species are capable of anterior regeneration.

- Houseflies have an average lifespan of 20 to 30 days, not 24 hours. However, members of one species of mayfly have an adult lifespan of as little as 5 minutes.

- The daddy longlegs spider (Pholcidae) is not the most venomous spider in the world. Their fangs are capable of piercing human skin, but the tiny amount of venom they carry causes only a mild burning sensation for a few seconds. Other species such as harvestmen and crane flies are also called daddy longlegs, and share the misconception of being highly venomous but unable to pierce the skin of humans.

- People do not swallow large numbers of spiders during sleep. A sleeping person makes noises that warn spiders of danger. Most people also wake up from sleep when they have a spider on their face.

- Female praying mantises do not always eat the males during mating.

- It is not true that aerodynamic theory predicts that bumblebees should not be able to fly; the physics of insect flight is quite well understood. The misconception appears to come from a calculation based on a fixed-wing aircraft mentioned in a 1934 book, and was further popularized in the 2007 film Bee Movie.

- While certainly critical to the pollination of many plant species, European honey bees are not essential to human food production, despite claims that without their pollination, humanity would starve or die out "within four years". In fact, the most essential staple food crops on the planet, like wheat, maize, rice, soybeans and sorghum are wind pollinated or self pollinating, and only slightly over 10% of the total human diet of plant crops is dependent upon insect pollination.

- Bees do not always die if they use their sting. This only happens for a very small minority of species, which includes the honey bee, when they sting mammals, as they have thick skin. They are able to survive when they sting other insects.

- Earwigs are not known to purposely climb into external ear canals, though there have been anecdotal reports of earwigs being found in the ear. The name may be a reference to the appearance of their hindwings, which are unique and distinctive among insects, and resemble a human ear when unfolded.

- Ticks do not jump or fall from trees onto their hosts. Instead, they lie in wait to grasp and climb onto any passing host or otherwise trace down hosts via, for example, olfactory stimuli, the host's body heat, or carbon dioxide in the host's breath.

- Though they are often called "white ants", termites are not ants, nor are they closely related to ants. Termites are actually highly derived cockroaches.

- Cockroaches would not be the only organisms capable of surviving in an environment contaminated with nuclear fallout. While cockroaches have a much higher radiation resistance than vertebrates, they are not immune to radiation poisoning, nor are they exceptionally radiation-resistant compared to other insects.

- Applying urine to jellyfish stings does not relieve pain; indeed, it may make the pain worse. The best immediate treatment for jellyfish stings is to rinse them in salt water.

Plants

[edit]- Carnivorous plants can survive without food. Catching insects, however, supports their growth.

- Poinsettias are not highly toxic to humans or cats. While it is true that they are mildly irritating to the skin or stomach, and may sometimes cause diarrhea and vomiting if eaten, they rarely cause serious medical problems.